Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

The European Journal of Psychiatry

versión impresa ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.27 no.3 Zaragoza jul./sep. 2013

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S0213-61632013000300001

Alexithymia, depression, anxiety and binge eating in obese women

Agnieszka Źak-Gołąb*; Radosław Tomalski**; Monika Bąk-Sosnowska***; Michał Holecki****,*****; Piotr Kocełak******; Magdalena Olszanecka-Glinianowicz******; Jerzy Chudek* and Barbara Zahorska-Markiewicz*****

*Department of Pathophysiology, Medical University of Silesia, Katowice. Poland

**Day-care Psychiatric Ward "Feniks", Sosnowiec. Poland

***Department of Psychology, Medical University of Silesia, Katowice. Poland

****Department of Internal Medicine and Metabolic Diseases, Medical University of Silesia, Katowice. Poland

*****Obesity Management Clinic "Waga", Katowice. Poland

******Health Promotion and Obesity Management Unit, Department of Pathophysiology, Medical University of Silesia, Katowice. Poland

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives: Alexithymia is a personality trait that may affect the development and course of obesity and effectiveness of treatment. The aim of the study is to assess the prevalence of alexithymia in obese women beginning a weight reduction program and determine the relationships between alexithymia and anxiety, depression, and binge eating.

Methods: Obese women (n = 100; age 45 ± 13 yr) completed the following self-report inventories: Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS 26), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Binge Eating Scale (BES).

Results: Alexithymia was found in 46 patients and was more frequent among women who had attained only primary and vocational education than in those with a higher education level (39.1% vs. 10.9%; p = 0.002) and in those >45 years old than in younger women (30.4% vs. 69.6%; p = 0.03). The frequency of severe depression symptoms was higher in alexithymic women than in non-alexithymic women (19.6% vs. 5.6%; p = 0.03); however, the anxiety state was equally prevalent in both subgroups. The prevalence of alexithymia (52.6% vs. 44.4%) and its level (73.2 ± 8.9 vs. 71.2 ± 11.3 points) were similar in women with and without binge eating disorder. Multivariate mixed linear regression analysis revealed that higher body mass index was associated with primary and vocational education (odds ratio [OR] = 16.69) and severe depression symptoms (OR = 52.45), but not alexithymia.

Conclusions: In addition to severe depression and low education level, obesity may predispose for the development of alexithymia. However, alexithymia does not affect the severity of obesity in women.

Key words: Alexithymia; Anxiety; Binge eating; Depression; Obesity.

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity is increasing worldwide1-4. It is a major health problem and an important risk factor for type 2 diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, sleep apnea, and cancer5-7.

The etiology of obesity is complex and multidimensional, and includes genetic, environmental, social, and psychological factors. A variety of factors, including negative thoughts and feelings about oneself, relationship problems, depression, anxiety, and somatomorphic disorders are common in overweight and obese subjects and may play an important role in the development and maintenance of obesity8-13. Conversely, mental distress may be caused by factors associated with obesity, such as eating a restrictive diet (currently or in the past), frequent weight cycling, and binge eating episodes14. Our previous study revealed a high prevalence of depression in obese subjects starting a weight loss program, which increased with the severity of obesity13.

Alexithymia is a personality trait that may affect the development and course of obesity, concomitant mental disorders, and the effectiveness of weight reduction therapy. Alexithymia, which literally means "no words for emotions," is characterized by the inability to identify and express emotions, an impoverished fantasy life and preference for concrete concerns15. Alexithymia also appears to play a role in the development of eating disorders, such as anorexia and bulimia nervosa16. However, the results of studies assessing the relationship between alexithymia and eating behaviors have been inconsistent10. The results of some studies suggest a bilateral relationship between alexithymia and obesity19,20. Some authors have reported that obesity favors the development of secondary alexithymia21,22, whereas others consider alexithymia a primary trait, predisposing for binge eating and obesity23,24. Finally, the high frequency of alexithymia in obese individuals has been reported to be a consequence of depression23,25.

Binge eating disorder (BED) is characterized by periods of extreme over-eating that are not followed by purging behaviors. The prevalence of BED among obese individuals seeking weight loss treatment has been estimated at 30%17. Binge eating behaviors are sometimes observed in women who do not meet the diagnostic criteria of BED according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition26.

The aim of the study is to assess the prevalence of alexithymia in obese women starting a weight reduction program and determine the relationships between alexithymia and anxiety, depression, and BED.

Patients and methods

We enrolled obese women without concomitant diseases and not taking any medications at the time of their first visit to the Obesity Management Clinic. A total of 100 women agreed to participate in the survey; only a few women chose not to participate. All subjects received a diagnosis of simple obesity. The study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Silesia. All subjects provided informed written consent to participate in the study.

Body mass and height were measured, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated by using the standard formula (kg/m2). Participants completed the following self-report inventories: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Binge Eating Scale (BES), and 26-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS 26). Polish versions of the TAS-26 and HADS, but not the BES, were previously validated in Poland27,28.

The TAS 26, a reliable and valid measure of alexithymia, consists of 26 items divided into four subscales: 1, difficulty in distinguishing feelings and bodily sensations; 2, external thinking; 3, inability to describe emotions; and 4, paucity of fantasy. Alexithymia was defined as a total score ≥74 points29.

The HADS contains two subscales, anxiety and depression, each consisting of seven items scored from 0 to 3. Out of a possible 21 points, 0-7 points were considered normal, 8-10 points considered borderline, and >11 points represented severe symptoms of anxiety and depression30.

The BES is a 16-item questionnaire used to assess the presence of binge eating behavior. Each question has three or four possible responses that are each assigned a numerical value. Out of a possible 46 points, >17 points indicated non-binging, 18-26 points indicated moderate binging, and ≥27 indicated severe binging31.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using Statistica 9.0 PL software. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or percentages. Subjects were divided into subgroups according to BMI, TAS scores, and BES scores. Normality of distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Chi-square test or Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare subgroups, when appropriate. Univariate correlation coefficients were calculated according to Spearman rank-order equation. Multivariate forward logistic regression analysis using the stepwise method included factors potentially favoring the occurrence of alexithymia: BMI, age, primary and vocational education, anxiety and depression level, and presence of BED. Odds ratios (ORs) are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI). To assess relationships between BMI and clinical parameters, a multivariate mixed linear regression model with random effect (age) was used with the backward stepwise procedure. Restricted maximum likelihood estimation was used as an optimization algorithm. Goodness of fit of the regression model was assessed with the Wald c2 test. The results were considered significant with a p-value <0.05.

Results

Alexithymia

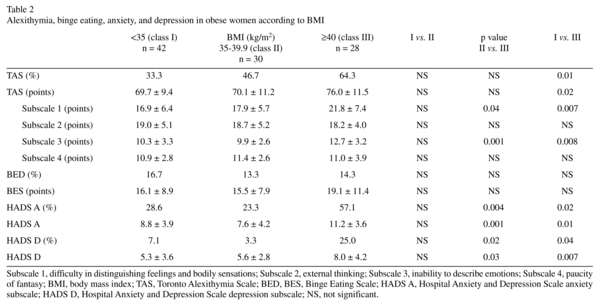

Alexithymia (TAS score ≥74 points) was found in 46/100 (46%) patients. The mean TAS score in the alexithymic patients was 80.7 ± 5.6 points. Patients with BMI ≥40 kg/m2 had the highest prevalence of alexithymia and the highest mean TAS score (Table 1 and 2). A significant correlation was observed between BMI and TAS score (r = 0.21, p = 0.04).

Alexithymia was more frequently diagnosed in women who had attained only primary and vocational education than in those who had attained a higher education level (Table 1), and was more frequent in women older than 45 years compared with younger women (30.4% vs.69.6%; p = 0.03).

The factors with the greatest effect on the TAS score were the inability to describe emotions (β = 1.26; p <0.001) and concrete thinking (β = 0.90; p <0.001).

Binge eating disorder

BED (BES score >26 points) was found in 19/100 (19%) study subjects. Although not significant, morbidly obese women had slightly higher BES scores (Table 2). A positive correlation was observed between BMI and BES score (r = 0.21, p = 0.04).

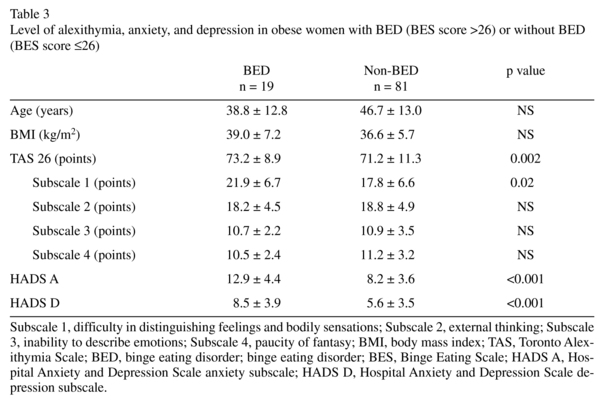

The prevalence of BED was similar between alexithymic and non-alexithymic subgroups (21.7% vs. 16.6%, NS). Although the prevalence of alexithymia did not differ significantly between women with or without BED (52.6% vs. 44.4%; NS), those with BED reported a greater difficulty distinguishing feelings and bodily sensations (p = 0.02) (Table 3).

Anxiety and depression

Symptoms of anxiety were observed in 38/100 (38%) women, and the anxiety level was markedly higher in the morbid obese subgroup (Table 2). Frequency of anxiety was similar between the alexithymic and non-alexithymic subgroups (41.3% vs. 35.2%; NS) but was significantly higher in the BED subgroup than in the non-BED subgroup (73.7% vs. 23.5%; p <0.001) (Table 3).

Twelve (12%) women scored ≥11 points on the HADS depression subscale, suggesting a state of depression; nine of these subjects also had alexithymia. Thus the frequency of depression was significantly higher in the alexithymic subgroup than in the non-alexithymic subgroup (19.6% vs. 5.6%; p = 0.03) and was higher in the BED subgroup than in the non-BED subgroup (26.3% vs. 8.6%; p = 0.03). Morbidly obese women had the highest HADS depression and anxiety scores (Table 2). Moreover, BMI was positively correlated with both anxiety (r = 0.23 p = 0.02) and depression (r = 0.24 p = 0.02).

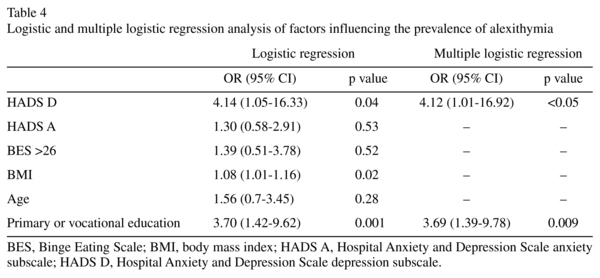

Regression analysis

Results of logistic regression analysis showed that alexithymia was associated with depression (OR = 4.14 [1.05-16.33]), BMI (OR = 1.08 [1.01-1.16]), and primary or vocational education (OR = 3.70 [1.41-9.62]). Multiple regression analysis confirmed that depression and primary/vocational education, but not BMI, were independent predictors of alexithymia (Table 4).

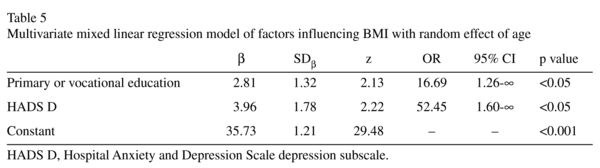

The multivariate mixed linear regression model with random effect (age) revealed that primary and vocational education (OR = 16.69 [1.26-∞]) and depression (OR = 52.45 [52.45-∞], but not alexithymia, are predictors of BMI (goodness of fit, c2 Wald = 10.12; p<0.01; log REML = -313) (Table 5).

Discussion

The results of our study revealed that depression and low educational level were associated with alexithymia in obese women starting weight reduction therapy; however, alexithymia was not associated with BMI.

The prevalence of alexithymia in our study population was relatively high (46%) but within the previously reported range (24.1%-52.1%)10,19,29,32,33,34. The frequency of this personality trait increased with severity of obesity, from 33.3% (class I obesity) to 64.3% (morbid obesity). External thinking and inability to describe emotions accounted for most of the variability in the TAS score in obese. This finding was consistent with that of a previous study, which suggested that externally oriented thinking is the most pronounced aspect of alexithymia in obese patients35. A more concrete style of thinking can translate into a reduced interest in one's own inner life, overeating, or a sedentary lifestyle. Results obtained by Helmers et al. suggest that components of alexithymia (e.g., difficulty identifying emotions) are associated with malnutrition and alcohol and drug abuse, whereas difficulty communicating emotions is associated with a sedentary lifestyle36.

The association between alexithymia and morbid obesity suggests that alexithymia plays a role in further weight gain in obese individuals. However, multivariate mixed linear regression analysis failed to confirm this hypothesis, showing only the influence of depression and low educational level on the severity of obesity. These findings suggest that the higher incidence of alexithymia in patients with morbid obesity is secondary to coexisting depression, and that alexithymia appears as a temporary state in this group. A previously published study reported that alexithymia occurred more frequently in obese individuals than in those with normal weight37. Thus, our findings do not exclude a direct link between alexithymia and obesity.

It should be emphasized that the prevalence of alexithymia in obese individuals is influenced by additional factors including gender, age, and education level. Consistent with the results of previously published studies, we also observed a relationship between lower education level and alexithymia38-40 and a higher prevalence of alexithymia in obese women older than 45 years41,42.

We further evaluated other factors (depression, anxiety, and binge eating) that could potentially influence the occurrence of alexithymia in obese individuals. We found that the prevalence of depression in our study population (12%) was lower than that of previous studies13,43. This difference may be due to the different screening inventories used, with some scales detecting only severe depression. In our study, high levels of depression were more frequently found in alexithymic women than in non-alexithymic women (19.6% vs. 5.6%). Some studies have reported that alexithymia is common in depressed subjects, and Honkalampi et al.44 demonstrated that severe depression is independently associated with alexithymia. However, data showing the prevalence of depression in alexithymic obese individuals are limited. Pinaquy et al. showed a positive correlation between TAS and depression score only in obese subjects without BED, suggesting the primary nature of alexithymia in subjects with BED23. Additionally, Da Rose et al. reported recently that difficulties in distinguishing emotions and inability to describe emotions were associated with depression symptoms in obese individuals45.

Some authors have suggested that alexithymia in obese individuals is related to BED23,46, because this personality trait frequently coexists with anorexia and bulimia nervosa45,47. However, our results, which are similar to those obtained by Zwaan et al.17 and de Chouly de Lenclave et al.48, did not confirm this hypothesis, because the prevalence of alexithymia and total TAS scores were similar in the BED and non-BED subgroups. On the other hand, de Zwaan et al. and our group observed a higher level of difficulty in distinguishing between feelings and bodily sensations, a characteristic alexithymic feature, among BED subjects49, but we did not find a higher prevalence of BED among morbidly obese women. The reason for this is unclear but may be related to other factors influencing BED development that differ among study populations (e.g., depression level and alexithymia). Thus, BED frequency may be similar among different classes of obesity because the occurrence of alexithymia is not affected by level of depression.

Our results indicate the importance of screening for alexithymia, depression, and BED in obese subjects in daily clinical practice and, when appropriate, referral for psychotherapy. Individualized cognitive-behavioral therapy may improve the effectiveness of weight loss management, at least in some patients.

The limitations of our study are its relatively small sample size and the lack of a normal-weight control group. Moreover, we recruited obese women who were seeking help with weight loss, so our study population cannot be considered a representative sample of obese individuals in the general population. Additionally, assessments of alexithymia, BED, anxiety, and depression were based on self-report inventories only. Thus, the results of our study should be considered preliminary findings.

Conclusions

In addition to severity of depression and low education level, obesity may predispose for the development of alexithymia. However, alexithymia does not affect the severity of obesity in women.

References

1. Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Liang L, Caballero B, Kumanyika SK. Will all Americans become overweight or obese? Estimating the progression and cost of the US obesity epidemic. Obesity 2008; 16(10): 2323-2330. [ Links ]

2. Flegal KM, Caroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008. JAMA 2010; 303(01): 235-241. [ Links ]

3. James WP. The epidemiology of obesity: the size of the problem. J Internal Medicine 2008; 263(4): 336-352. [ Links ]

4. Branca F, Nikogosian H, Lobstein T. The challenge of the obesity in the WHO European region and the strategies for response: Summary. Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe. 2007. [ Links ]

5. Adams KF, Schatzkin A, Harris TB, Kipnis V, Mouw T, Ballard-Barbash R, et al. Overweight, obesity and mortality in a large prospective cohort of persons 50 to 71 years old. N Engl J Med 2006; 355(25): 763-778. [ Links ]

6. Shepard A. Obesity: prevalence, causes and clinical consequences. Nurs Standard 2009; 23(52): 51-57. [ Links ]

7. Cameron AJ, Dunstan DW, Owen N, Zimmet PZ, Barr EL, Tonkin AM, et al. Health and mortality consequences of abdominal obesity: evidence from the AusDiab study. Med J Aust 2009; 191(4): 202-208. [ Links ]

8. Becker E, Margraf J, Turke V, Soeder U, Neumer S. Obesity and mental illness in a representative sample of young women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25 (Suppl. 1): S5-S9. [ Links ]

9. Ashmore JA, Friedman KE, Reichmann SK, Musante GJ. Weight-based stigmatization, psychological distress and binge eating behavior among obese treatment-seeking adults. Eating Behavior 2008; 9(2): 201-209. [ Links ]

10. Adami G, Campostano A, Ravera G, Leggieri M, Scopinaro N. Alexithymia and body weight in obese patients. Behav Med 2001; 27(3): 121-126. [ Links ]

11. Hrabosky JL, Thomas JJ. Elucidating the relationship between obesity and depression: recommendations for future research. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2008; 15(1): 28-34. [ Links ]

12. Kasen S, Cohen P, Chen H, Must A. Obesity and psychopathology in women: a three decade prospectice study. Int J Obes 2008; 32(3): 558-566. [ Links ]

13. Olszanecka-Glinianowicz M, Zahorska-Markiewicz B, Kocelak P, Semik-Grabarczyk E, Dabrowski P, Gruszka W, et al. Depression in obese persons before starting ciomplex group weight-reduction programme. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2009; 55(5): 407-413. [ Links ]

14. Friedman MA, Brownell KD. Psychological correlates of obesity: moving to the next research generation. Psychol Bull 1995; 117(1): 3-20. [ Links ]

15. Sifneos P. Alexithymia: past and present. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153(7): 137-142. [ Links ]

16. Cochrane C, Brewerton T, Wilson D, Hodges E. Alexithymia in the eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 1993; 14(2): 219-222. [ Links ]

17. De Zwaan M. Binge eating disorder and obesity. Int J Obes 2001; 25(Suppl. 1): S51-S55. [ Links ]

18. Wheeler K, Greiner P, Boulton M. Exploring alexithymia, depression and binge eating in self-reported eating disorders in women. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2005; 41(3): 114-123. [ Links ]

19. Legoretta G, Bull R, Kiely M. Alexithymia and symbolic function in the obese. Psychother Psychosom 1988; 50(2): 88-94. [ Links ]

20. Clerici M, Albonetti S, Papa R, Penati G, Invernizzi G. Alexithymia and obesity. Study of the impaired symbolic function by the Rorschach test. Psychother Psychosom 1992; 57(3): 88-93. [ Links ]

21. Lumley MA, Stettner L, Wehmer F. How are alexithymia and physical illness linked? A review and critique of pathways. J Psychosom Res 1996; 41(6): 505-518. [ Links ]

22. Grabe HJ, Schwahn C, Barnow S, Spitzer C, John U, Freyberger HJ. Alexithymia, hypertension, and subclinical atherosclerosis In general population. J Psychosom Res 2010; 68(2): 139-147. [ Links ]

23. Pinaquy S, Chabrol H, Simon C, Louvet JP, Barbe P. Emotional eating, alexithymia, and binge-eating disorder in obese women. Obes Res 2003; 11(2): 195-201. [ Links ]

24. Larsen JK, Brand N, Bermond B, Hijman R. Cognitive and emotional characteristics of alexithymia: a rewiew of neurobiological studies. J Psychosom Res 2003; 54(6): 533-541. [ Links ]

25. de Groot JM, Rodin G, Olmsted MP. Alexithymia, depression and treatment outcome in bulimia nervosa. Compr Psychiatry 1995; 36(1): 53-60. [ Links ]

26. Wheeler K, Greiner P, Boulton M. Exploring alexithymia, depression and binge eating in self-reported eating disorders in women. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2005; 41(3): 114-123. [ Links ]

27. Maruszewski T, Scigala E. Emotions-alexithymia-cognition. Poznan, Wydawnictwo Fundacji Humaniora; 1998. [ Links ]

28. Majkowicz M. Practical evaluation of the effectiveness of palliative care - selected research techniques. In: de Walden-Galuszko K, Majowicz M, eds. Evaluation of the quality of palliative care in theory and practice. First edition. Gdansk: Akademia Medycyny Paliatywnej; 2000. p. 34-36. [ Links ]

29. Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Ryan DP, Parker JD, Doody KF, Keefe P. Criterion validity of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale. Psychosom Med 1988; 50(5): 500-509. [ Links ]

30. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 67(6): 361-370. [ Links ]

31. Gormally J, Black S, Daston S, Rardin D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict Behav 1982; 7(1): 47-55. [ Links ]

32. Morosin A, Riva G. Alexithymia in a clinical sample of obese women. Psychol Rep 1997; 80(2): 387-394. [ Links ]

33. Fukunishi I, Kaji N. Externally oriented thinking of obese men and women. Psychol Rep 1997; 57(1): 88-93. [ Links ]

34. Noli G, Cornicelli M, Marinari GM, Carlini F, Scopinaro N, Adami GF. Alexithymia and eating behavior in severely obese patients. J Hum Nutr Diet 2010; 23(6): 616-619. [ Links ]

35. Elfhag K, Lundh LG. TAS 20 alexithymia in obesity and its links to personality. Scand J Psychol 2007; 48(5): 391-398. [ Links ]

36. Helmers KF, Mente A. Alexithymia and heath behaviors in healthy male volunteers. J Psychosom Res 1999; 47(6): 635-645. [ Links ]

37. Morosin A, Riva G. Alexithymia in a clinical sample of obese women. Psychol Rep 1997; 80 (2): 387-394. [ Links ]

38. Posse M, Hallstrom T, Backenroth-Ohsako G. Alexithymia, social support, psycho-social stress and mental health in a female population. Nord J Psychiatry 2001; 42(2): 471-479. [ Links ]

39. Carano A, De Berardis D, Gambi F, Di Paolo C, Campanella D, Pelusi L, et al. Alexithymia and body image in adult outpatients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 2006; 39(4): 332-340. [ Links ]

40. Mattila AK, Salminen JK, Nummi T, Joukamaa M. Age is strongly associated with alexithymia in the general population. J Psychosom Res 2006; 61(5): 629-635. [ Links ]

41. Tolmunen T, Heliste M, Lehto SM, Hintikka J, Honkalampi K, Kauhanen J. Stability of alexithymia in the general population: an 11-year follow-up. Compr Psychiatry 2011; 52(5): 536-541. [ Links ]

42. Roberts RE, Deleger S, Strawbridge WJ, Kaplan GA. Prospective association between obesity and depression: Evidence from the Alameda Country Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003; 27(4): 514-521. [ Links ]

43. Schmidt U, Jiwany A, Treasure J. A controlled study of alexithymia in eating disorders. Compr Psychiatry 1993; 34(1): 54-58. [ Links ]

44. Honkalampi K, Hintikka J, Laukkanen E, Lehtonen J, Viinamäki H. Alexithymia and depression: a prospective study of patients with major depressive disorder. Psychosomatics 2001; 42(3): 229-234. [ Links ]

45. Da Ros A, Vinai P, Gentile N, Forza G, Cardetti S. Evaluation on alexithymia and depression in severe obese patients not affected by eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord 2011; 16(1): e24-29. [ Links ]

46. Pinna F, Lai L, Pirarba S, Orru W, Velluzzi F, Loviselli A, et al. Obesity, alexithymia and psychopathology: A case-control study. Eat Weight Disord 2011; 16(3): 164-170. [ Links ]

47. De Groot JM, Rodin G, Olmsted MP. Alexithymia, depression and treatment outcome in bulimia nervosa. Compr Psychiatry 1995; 36(1): 53-60. [ Links ]

48. De Chouly De Lenclave MB, Florequin C, Bailly D. Obesity, alexithymia, psychopathgology and binge eating: a comparative study of 40 obese patients and 32 controls. Encephale 2001; 27(4): 343-350. [ Links ]

49. de Zwaan M, Bach M, Mitchell JE, Ackard D, Specker SM, Pyle RL, et al. Alexithymia, obesity and binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 1995; 17(2): 135-140. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Agnieszka Źak-Gołąb, MD, PhD

Department of Pathophysiology

Medical University of Silesia

12 Medyków Street

40-752 Katowice

Poland

Tel./Fax. +48 32 2526091

E-mail: agzak@poczta.onet.pl

Received: 14 February 2012

Revised: 8 January 2013

Accepted: 22 March 2013