Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Medicina y Seguridad del Trabajo

versión On-line ISSN 1989-7790versión impresa ISSN 0465-546X

Med. segur. trab. vol.60 no.234 Madrid ene./mar. 2014

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S0465-546X2014000100015

REVISIONES

Current framework of suicide and suicidal ideation in health professionals

Marco actual del suicidio e ideas suicidas en personal sanitario

M. Cano-Langreo1,3, S. Cicirello-Salas1,3, A. López-López1,3, M. Aguilar-Vela2,3

1. Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos. Madrid. España.

2. Facultad de Ciencias y Filosofía "Alberto Cazorla Talleri", Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia. Perú.

3. Unidad Docente de Medicina del Trabajo de la Comunidad de Madrid. Madrid. España.

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Suicide is a public health problem in many countries. Several studies have shown occupational risk factors associated with suicidal ideation and high suicide rates in health care workers with respect to the general population.

Objectives: To describe the current status of suicide in health care workers and assess demographic characteristics, occupational factors associated with suicidal ideation, and trends according to geographic location and to compare them with the general population or other professions.

Method: Literature review in different databases in two stages: search/selection of items and assessment of 20 selected studies.

Results: Health care workers have a higher risk of suicide compared with the general population and other professions. Increased risk was observed in the areas of nursing, pharmacy, dentistry, and medicine. The medical specialties with the highest risk are anesthesiology and psychiatry, being higher in women and at an older age. Regarding the most used methods, subjects in the USA prefer firearms while in other countries they prefer an overdose of drugs. Recent unpleasant experiences/workplace harassment, burnout, and labor disputes have proven risk factors in suicidal ideation in doctors.

Conclusions: There are demographic differences in the characteristics of suicide according to different studied populations. The methods employed by physicians per countries are different, possibly due to the cultural influence of each country. Associated factors have been found between risk and suicidal ideation. It would be important to work on them to develop prevention strategies in this population.

Key words: Suicide, physicians, nurse, health personnel, work-related, risk.

RESUMEN

Introducción: El suicidio es un problema de salud pública en muchos países. Varios estudios han demostrado factores de riesgo laborales asociados a ideación suicida y altos índices de suicidio en el personal sanitario con respecto a la población general.

Objetivos: Describir la situación actual del suicidio en el personal sanitario y evaluar las características demográficas, factores laborales relacionados con ideación suicida y tendencias de acuerdo a la localización geográfica y además compararlas con la población general u otras profesiones.

Método: Revisión bibliográfica en diferentes bases de datos, en dos fases: búsqueda/selección de artículos y evaluación de 20 estudios seleccionados.

Resultados: El personal sanitario tiene mayor riesgo de suicidio comparado con la población general y otras profesiones. Se evidenció mayor riesgo en los sectores de enfermería, farmacéutico, odontología y medicina. Las especialidades médicas con mayor riesgo son anestesiología y psiquiatría. La tasa de suicidio es mayor en mujeres. Se objetiva mayor riesgo en grupos de mayor edad. En cuanto los métodos más utilizados en EEUU son las armas de fuego, mientras que en otros países es la sobredosis de drogas. Las experiencias desagradables recientes/acoso laboral, el burnout y conflictos laborales han demostrado ser factores de riesgo en la ideación suicida en médicos.

Conclusiones: Existen diferencias demográficas en las características del suicidio de acuerdo a diferentes poblaciones estudiadas. Los métodos empleados en médicos por países son diferentes, que posiblemente se deban a la influencia cultural de cada país. Se han encontrado factores asociados entre riesgo e ideación suicida. Sería importante trabajar en ellos para elaborar estrategias de prevención en esta población.

Palabras clave: Suicidio, médico, enfermera, personal sanitario, laboral, riesgo.

Introduction

Suicide is a public health problem. In Spain, during the period of 2009-2010, suicide was the first external cause of death, with 3.145 deaths, above traffic accidents 1.

Two recent studies conducted simultaneously in several European countries, including Spain, have provided data on the incidence of suicidal ideation and the existence of different risk factors potentially linked to their existence and to the path from suicidal ideation to suicide attempts. In the first of these, the European Study on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMED), a cross-sectional study performed in six European countries on a total sample of 21,425 people (2,121 from Spain) found a prevalence of 4.4% for suicide ideation and 1.5% for suicide attempts in Spain, while the European average for suicidal ideation was 7.8% and for suicide attempts 1.8 %. In the second one, the Outcome for Depression International Network (ODIN), the presence of suicidal ideation was analyzed in a random sample of 7,710 people in five European countries. In the Spanish sample it was found that 2.3% of the adult population between 18 and 65 had some degree of suicidal ideation, a relatively low rate compared to that of other European countries included in the study (7.4% in Norway and Wales, 9.8 % in Finland and 14.6 % in Ireland)2.

Various studies have shown lower mortality rates in Health professionals than in the general population 3-5; however, in terms of suicide, it has been proposed that health professionals present higher risks. Several studies have shown higher rates of suicide in health professionals than in the general population and other professionals. The rate of male physicians is slightly higher, while the rate of female physicians is clearly superior. Higher rates relative to specialty have also been observed, being higher in anesthetists and psychiatrists 6-9. It is known that in many cases physicians have specific health care needs and sometimes this leads them to high levels of substance abuse and mental illness 10. These features can be related to the high stress and responsibility of their work, as well as to the difficulties in reconciling family and work life. It is also important to note the difficulties they face to discuss their problems with colleagues for fear of affecting their professional judgment, so they often resort to self-diagnosis and self-treatment dangerously. After studying other professions, increased risks have been highlighted in nurses, dentists, and pharmacists 11. Regarding suicide methods, differences were found depending on the profession. It appears that in the health sector the use of toxics stands out; the easy access to them and knowledge of their use could explain these differences 8.

The main objective of this study is to describe the current status of suicide in health professionals, as well as to evaluate the differences in prevalence of suicide according to different occupations. In addition, this study aims to know the demographics of suicide in the health workforce and to compare them to those of the general population, to compare different suicide trends according to the geographical location of the studied populations and their occupations, and to assess the risk factors associated with suicidal ideation.

Methodology

A bibliographic search was performed in the databases of MEDLINE (via PubMed), OSH-UPDATE, EMBASE, WOK, LILACS, Cochrane Library, and IBECS. The search was completed with scientific literature obtained in SciELO repository, Google, and other sources of gray literature, as well as articles referenced in the main works that were included in the study.

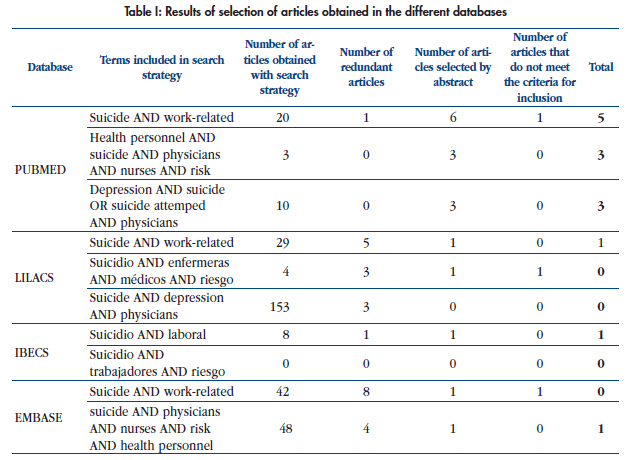

Different search strategies were defined using "MeSH-MeSH" descriptors and free terms for MEDLINE, LILACS, and IBECS, as well as free language for searches in the other databases (Table I). In the search strategy, Boolean combinations (AND, OR) of the following terms were used: Suicide, work-related, physician, nurse, health personnel, risk, suicide-attempt, and depression.

In Google, the search was performed in Spanish using the words "medicos", "suicidio", "riesgo" and "laboral", with different combinations.

The inclusion criteria were the following:

— Articles that deal with sociodemographic variables related to suicide in health personnel (physicians and nurses).

— Articles that provide data on the socioeconomic impact of suicide at work.

— Trials, experimental studies, meta-analyzes, systematic reviews, cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional observational studies.

The exclusion criteria were the following:

— Articles that deal exclusively with suicide in other health professionals (veterinarians).

— Articles that refer exclusively to the exposition of particular cases of suicide.

— Articles focused on the pharmacological management of depression and prevention of suicide.

— Articles that deal with strategies and programs for suicide prevention.

— Articles from which the complete original one could not be obtained.

The search limits used were the following:

— Period of publication of articles: from 2004 to 2013.

— Population: health personnel.

— Languages: English and Spanish.

The last date of search in the databases was January 2, 2014.

A bibliographic collection of a total of 530 articles was obtained, to which a first filter was performed to rule out duplicate, redundant, and irrelevant articles, leaving a total of 23 articles, to which the inclusion and exclusion criteria described previously were applied. Finally, 20 articles that met the conditions for the study were selected (Table I).

Results

Table II summarizes the twenty articles that were analyzed (one observational descriptive, one case-control, three case-control nested in a cohort, one cohort, thirteen cross-sectional, and one meta-analysis) regarding the characteristics of suicide and suicidal ideation in health personnel. Among the reviewed studies, we can distinguish two ways of addressing the issue of suicide: twelve articles study consummated suicide, and eight of them evaluate suicidal ideation.

Consummated suicide

twelve articles deal with consummated suicide. In all of them, a sample extraction was performed through an analysis of the death registration data of the respective countries.

Comparison between health professionals and other professionals

Ten articles compare the prevalence of suicide in healthcare workers to that of other professionals. Gagné et al. studied suicides recorded during the period 1992-2009 in Quebec, noting that physicians represent 2.6 % of suicides in this period 12.

A study conducted by Hem et al. on suicides in Norway during the period 1960-2000 shows that the highest rates of suicide during this period are found in male physicians (43 CI95% 35,3-52,5), dentists (32,9 CI95% 23,3-46,5), female physicians (26,1 CI95% 15,2-44,9) and male nurses (24,4 CI95% 14,4-41,1)13. Also, in the studies of Skegg et al. and Stallones et al, higher rates of mortality by suicide were found in health professionals than in other professionals4,15.

Schernhammer et al. published a meta-analysis of 25 studies of quality, which include European and North American populations, concluding that the risk of suicide is higher in physicians than in the general population and higher in female physicians than in the general population (male physicians: RR 1.41 CI95% 1.21-1.65; female physicians: RR 2.27 CI95% 1.90-2.73)9.

Three of the articles included in the study compare the risk of suicide among the population of health professionals with respect to teachers and with respect to the general population, taking the last two as a reference. In those groups a higher risk of suicide was found in the sector of medical professionals and nurse professionals with respect to the reference groups16-18. Also, one of the articles observes a higher risk in other health professionals such as dentists and pharmacists16.

Austin et al. studied physicians from Australia and found a high rate of suicide in female physicians compared to the general population (SRR 2.39 CI95% 1.52-3.77). For male physicians and dentists the rate was lower than the rate in the general population (0.80 CI95% 0.53-1.20 y 0.68 CI95% 0.52-0.89, respectively)19.

A study in Taiwan by Shang et al. analyzed the causes of death in physicians over a period of 16 years and found that physicians are less likely to die from any cause, including suicide, than the general population4.

Comparison among different health specialties

Within different health specialties, Austin et al. reported that the main specialties that consummated suicide during the years of the study (1997-2011) were anesthetists (44.4 %), psychiatrists (22.2%), family physicians (22.2%), and surgical residents (12.2 %)19.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Gender

Five studies compare the risk of suicide between gender, and four of them conclude that the risk is greater in men9,15,19,20. The meta-analysis included in the review makes a comparison among rates standardized by gender and concludes that these values are reversed with respect to the general population9. Agerbo et al. found that women who work in male-dominated professions have a higher risk of suicide than those who work in female-dominated professions (RR 1.68, IC95% 1.06-2.68)17.

Age

Four of the reviewed articles compare suicide mortality by age, and the majority conclude that the risk increases with age13,20,21.

Gagné found that women who consummated suicide did so at a younger age than men12.

Marital status

One of the reviewed articles found a higher proportion of suicide in married physicians than in unmarried ones (OR 1.7 IC95% 1.27- 2.28)20; however, another article did not find significant differences in suicide risk as a function of marital status in the studied population18. Gagné et al. observed an increased tendency of suicidal physicians to live in couples in comparison with the control groups (51.6% vs 31.4%)12.

Method of suicide

In their study, Austin et al. reported that most cases of suicide were by drug overdose (89.9%), and the most commonly used substances were anesthetics, barbiturates, and opiates19.

Three of the studies evaluated the trends of the employed suicide method by profession and found significant differences in the use of drugs as a method of suicide, their use being greater in healthcare professionals compared to the control groups14,16,18. In one of the studies it was observed that female physicians, nurses, and pharmacists chose this method of suicide more often, especially female physicians (X2=19.3 p< 0,001)16.

In a study of the populations of 16 U. S. states, Gold et al. published that the most prevalent method of suicide in medical professionals is suicide with a firearm (48%), and the second most common is poisoning (23.5%). In non-medical professionals, the most prevalent method was suicide by firearm (54%), followed by asphyxia (22%). The third cause was poisoning (18%)20.

In their study in Canada, Gagné et al. reveal that hanging was the most used method for suicide in both medical professionals (41.7%) and non-medical professionals (50%). Statistically significant differences were not found when comparing the specific methods of suicide in the different groups, although in absolute percentages firearms were employed more frequently in the general population than in physicians (13.9% vs 5.6%) and poisoning was more frequent in physicians than in the general population (30.6% vs 16.7%)12.

Psychosocial factors related to suicide

Associated psychiatric disorders

Two articles found that a high percentage of health professionals had been diagnosed with a mental disorder, the most common being unipolar depression12,18. In one of them, it is indicated that in the different groups of health professionals who had committed suicide the prevalence of mental disorder was higher than in the group of teachers and the general population, these differences being statistically significant (X2= 10.8 df=3 p= 0.013)18. On the other hand, Hawton et al. did not find any statistically significant difference between health professionals with a previous psychiatric history and those without it16. Gold et al. also report that there were no significant differences in the existence of mental illness between the two suicidal groups (physicians 46% vs. other medical occupations 41%), nor in the presence of depressed mood at the time of suicide (42% vs 39%)20.

In their study, Agerbo et al. found that those who have no contact with psychiatric services have a lower risk of suicide, whereas in the health professionals these differences are not observed17.

Alcohol and drug abuse

The two studies that include the variables of consumption of alcohol and other drugs found that physicians who committed suicide were less likely to consume these substances (Gold 14%vs23%, p=0,004)12,20.

Work problems

Gold et al. found that the relationship between work problems and suicide risk is higher among physicians (OR 3.12, CI95% 2.10-4.63), while having a labor crisis in the past two weeks or the death a friend or family member was associated with an increased risk of suicide in the non-medical personnel20.

Kolves et al. found significant differences in the prevalence of suicide related with work problems for different professionals. These problems were more prevalent in physicians (18.5%), followed by teachers (16.5%), and much lower in nurses (6.8%) and in the rest of the population (4.8%; X2 34.28 df=3 p<0.0019)18.

Suicidal ideation

Eight of the articles deal with suicidal ideation in health personnel. In all of them the information for the studies was obtained by surveying professionals from the sector.

Comparison between health professionals and other professionals

A study found a prevalence of suicidal ideation of 6.4% in American surgeons. Compared with the general population, significant differences between groups were found only when stratification by age was performed, with the highest prevalence in the group of surgeons in the groups of 45-54, 55-64, and over 65 years22.

Prevalence of suicidal ideation by health specialty

Anesthetists

Lindfors et al. found that 25% of the Finnish anesthetists that were surveyed had presented suicidal ideation, 22% had considered suicide, and 2% had planned it at some time23.

Physicians without distinguising specialty

Fridner et al, with the data from the HOUPE study in 2009, found a prevalence of suicidal ideation in 13.7% of female physicians in Sweden and 14.3% of female physicians in Italy24. When the data of male physicians was analyzed in 2011, a prevalence of suicidal ideation of 12% was found in both countries25.

Rosta et al. evaluated suicidal ideation in physicians through a Likert type survey on suicidal ideation in 2000 and 2010, finding a decrease in suicidal ideation through time26.

Nursing

A prevalence of suicidal ideation of 6.2% was found in the Primary Care Nursing group27.

Residents

12% of Dutch residents have had at least one suicidal thought during the residency, being significantly higher in psychiatric residents (21.6 %; X2=35.86, p<0.001)28.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Gender

None of the 3 articles that compares suicidal ideation in genders found significant differences between both sexes22,27,28.

Age

A study found differences in suicidal ideation of American surgeons in the different age groups, with the highest prevalence in the group of 45 to 54. Also, the study found that those over 65 tend to reduce suicidal ideation significantly22. Two other studies did not find any significant association between age and suicidal ideation27,28.

Marital status / Family life

Two studies evaluated socio-family factors that might be related to the presence of suicidal ideation. It was found that married surgeons have a lower tendency to suicidal ideation, as well as those with children, while divorced surgeons present an increased risk of suicidal ideation22. Another study concludes that physicians with poor health conditions, those with low social support, and those with family problems are more likely to present suicidal ideation23.

Psychosocial factors related to suicidal ideation

Psychiatric history

Two authors found a statistically significant relationship between the presence of depressive symptoms and the risk of suicidal ideation22,23. Moreover, those with suicidal ideation were more likely to consult with a mental health specialist and to take medication in the past 12 months.

In 2012, Fridner et al. found that 79.2% of physicians with suicidal ideation had not sought help for depression or burnout. They try to identify which variables influence seeking help when suicidal ideas arise, observing that males with suicidal ideas who were engaged in research were more likely to avoid seeking help, while those who had had some unpleasant experience or harassment were more likely to consult29. In another study published in 2009, the same work group identified that self-diagnosis and self-treatment is related to recent suicidal ideation in both Swedish and Italian female physicians (OR 2.12 CI95% 1.21-3.73)24.

Consumption of toxics and alcohol

A relationship between drug use and increased risk of suicidal ideation has been found in Finnish anesthetists. Also the harmful consumption of alcohol and the consumption of tobacco or snuffed drugs have been linked to increased risk of suicidal ideation23.

Work problems

Seven of the studies attempt to relate occupational factors to the risk of suicidal ideation22-28. Rosta et al. observed that having high levels of psychosocial stress at work acts as a predictor of suicidal ideation (OR 1.92 CI 95% 1.06-3.46 )26.

The HOUPE study has found labor factors that appear to be associated with the risk of suicidal ideation. They observed that going through a humiliating experience or workplace harassment increased the risk of suicidal ideation in Swedish female physicians and in Swedish and Italian male physicians. In female physicians of both countries they also found increased risk of suicidal ideation in those who sought help for depression or burnout. As protective factors for suicidal ideation, they found that meetings at work to deal with stressful situations or support at work when there were conflicts decreased the risk in Swedish female physicians and Italian and Swedish male physicians. In Italian physicians they also found that self-management of assigned work reduced the risk of suicidal ideation24,25.

Shanafelt et al. found a statistically significant relationship between suicidal ideation and burnout. The prevalence of suicidal ideation also increased relative to the severity of burnout, regardless of the existence of depression22. This relationship has also been found in residents28.

In another study, conflicts with colleagues and bosses as well as stress symptoms in relation to the medical guards are identified as the variables that are most strongly related to suicidal ideation23.

In the primary nurses, depression, anxiety, and emotional exhaustion were identified as predictor variables of suicidal risk27.

Discussion

Suicide at present in our environment is one of the first external causes of death in the general population1. The WHO has recently completed an action plan to identify risk factors for mental health, considering it a priority30. Related with this theme, several studies worldwide have analyzed the prevalence of consummated suicide and suicidal ideation in different professional groups. Many of them agree that the prevalence in health professionals is among the highest6,7,10,11, and most of the reviewed articles agree with this statement9,13,15-18. This could relate to the particular needs of this group, with conditions and work organization almost exclusively of this sector, dedicated to the care of patients, sometimes with the presence of situations of anxiety and helplessness. Furthermore, the traditional culture of medicine provides little importance to the mental health care of professionals, having little preparation in knowledge and psychosocial skills for these professionals to meet the challenges they face during their daily practice. Shang et al, however, found that the probability of death by suicide is lower in doctors than that in the general population. This could be explained because in the place of the study (Taiwan) there are very high rates of suicide in the general population. In addition, it is the only study found in Asia, while the others analyze Western populations with different psychosocial characteristics4. The healthcare industry is included within a social structure that varies widely from country to country.

In many occasions suicide prevalences may be underestimated because they are based on death records, and when an event of such magnitude and impact as the suicide of a health professional occurs, this event may be included in the list of accidents to avoid social stigma. In the studies of suicidal ideation the same thing may occur, since they are based on self-administered surveys to assess the presence of suicidal ideation, and as described in other studies, physicians in particular have difficulties to recognize the presence of mental illness for fear of affecting their work life10.

Higher rates of suicide have been observed according to specialty, being the highest in anesthetists, psychiatrists, family physicians, and residents. Most studies explain that these results are due to an increased access to lethal methods19. This access to the different methods might also shed light on the fact that health professionals use toxics as a suicide method more often than the general population12,14,16,18,19. In most of the studies that deal with this subject, poisoning has been identified as the primary method of suicide. It is important to highlight that in one study conducted in the United States, the most prevalent method of suicide was the use of firearms, perhaps because of the relatively easy access to them in that country20. In another study in Canada, it is surprising that the most prevalent method of suicide in both the general population and physicians is hanging12.

In the meta-analysis performed by Schernhammer et al. the authors observe that the standardized suicide rate for women is higher than that of male physicians, which seems to be a trend in the other studies. These studies found that although in the general population the risk of suicide is higher in men than in women, in the population of health professionals the differences between genders are inverted9. Austin et al. comment that women who work in traditionally male professions have a higher risk of suicide. They may present additional pressure for their social role19.

It seems that some authors find increased risk in people who cohabit or are married, contrary to what was observed in previous studies. They try to reason it by saying that physicians are less likely to divorce than the working class in general12,18,20.

Various psychosocial factors associated with an increased risk of suicidal ideation have been identified22-28. Suicidal ideation is the most prevalent in the age group 45-54, while the risk seems to decrease in those over 6522. This could be explained because in middle age both professional and personal needs are in their time of greatest demand. It is surprising that the risk decreases with age, since these professions have a high personal involvement, building a circle around work life. It is possible that feelings of worry, boredom, anxiety or depression, loss of self-esteem, and feelings of worthlessness arise, predisposing these people to increased suicidal ideation. On the other hand those with higher rates of burnout or occupational hazards could see this moment as the break they have been expecting.

The relationship between depressive symptoms and the onset of suicidal ideation is expected in this sector. As in the general population, these results are shared by most studies22-24. Sometimes this mood can lead doctors to a greater consumption of toxic substances and alcohol as a form of evasion or self-treatment, an ineffective way to address mental distress10,23-24.

As a major finding, it is important to highlight that several studies have identified occupational factors that influence suicidal ideation22-28. A significant association between the existence of burnout and suicidal ideation has been found24-25. Also, it has been found that those professionals who seek help to treat depression or burnout present a higher risk of suicide24-26,28. This may occur because these people look for help when their defense mechanisms have been overwhelmed. Protective factors at work (self-management of time, support by colleagues and bosses, meetings to address conflicts) have also been identified24-25. These factors have been shown to promote a working environment with less psychosocial stress.

Conclusions

Most of the reviewed studies have observed an increased risk of suicide and suicidal ideation in health professionals compared to the general population and other occupations.

Among health professionals, some groups such as psychiatrists, anesthetists, and residents may present higher risks of suicide.

Although in the general population a higher risk of suicide has been observed in men than in women, among health professionals that order is reversed.

According to several studies, there is a relationship between suicide risk and age, with the highest risk in the elderly.

Among health professionals, the most employed method to commit suicide is the use of toxic substances or drugs, possibly because these professionals have greater access to them and know the effects of such substances.

In this systematic review it has been found that the physicians with suicidal ideation or those who consummated suicide were frequently affected with mental illness, the most prevalent being depression.

Among health professionals there is a tendency to avoid contact with mental health specialists, something that could be explained by the fear of social stigma and the fear of jeopardizing their careers. This may imply that in many cases these professionals compromise their own health and the safety of their patients.

Several factors have been found that are related to the work environment and that increase the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide. Burnout, work overload, work demands without adequate means, problems with coworkers or bosses, degradable or humiliating situations at work, and workplace harassment are risk factors of suicidal ideation. The support of the work environment in a crisis, the possibility to discuss stressful situations, and self-management of schedules or workload have been identified as factors that protect against suicide.

Identifying populations at higher risk of suicide and understanding the factors that influence these populations could help develop prevention strategies in this area.

It is important to highlight that our country lacks reliable records on the distribution of suicide by occupation. It would be interesting to have this information in order to launch studies in our country, know the real extent of the problem, and establish prevention strategies in the psychosocial field.

Referencias Bibliográficas

1. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Nota de prensa, defunciones según la causa de muerte año 2010. 20 Marzo 2012. http://www.ine.es/prensa/prensa.htm. Consultado el 15 de enero de 2014.

2. Pagina web, Prevención del Suicidio. Departamento de Psiquiatría Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. http://www.prevencionsuicidio.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=93&Itemid=151. Consultado el 15 de enero de 2014.

3. Aasland OG, Hem E, Haldorsen T, Ekeberg Ø. Mortality among Norwegian doctors 1960-2000. BMC Public Health 2011 Mar 22;11:173.

4. Shang TF, Chen PC and Wang JD. Mortality of doctors in Taiwan. Occup Med (Lond). 2011 Jan;61(1):29-32.

5. Torre DM, Wang NY, Meoni LA, Young JH, Klag MJ, Ford DE. Suicide compared to other causes of mortality in physicians. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2005 Apr;35(2):146-53.

6. Hawton K, Clements A, Sakarovitch C, Simkin S, Deeks JJ. Suicide in doctors: a study of risk according to gender, seniority and specialty in medical practitioners in England and Wales, 1979-1995. J Epidemiol Community Health 2001 May;55(5):296-300.

7. Lindeman S, Laara E, Hakko H, Lonngvist J. A sistematic review on Gender-specific suicide mortality in medical doctors. Br J Psychiatry 1996 Mar; 168 (3): 274-9.

8. Lagro-Janssen AL, Luijs HD. Suicide in female and male physicians. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2008 Oct 4; 152(40): 2177-81.

9. Schernhammer ES, Colditz GA: Suicide rates among physicians: a quantitative and gender assessment (meta-analysis). Am J Psychiatry 2004 Dec;161 (12): 2295-302.

10. Mingote J C, Crespo D, Hernández M, Navío M, Rodrígo C. Prevención del suicidio en médicos. Med Segur Trab (Internet) 2013; 59 (231) 176-204.

11. Hawton K, Vislise lL.Suicide in nurses.Suicide Life Threat Behav.1999; 29 (1):86-95.

12. Gagné P, Moamai J, and Bourget D. Psychopathology and Suicide among Quebec Physicians: A Nested Case Control Study. Depress Res Treat. 2011;2011:936327.

13. Hem E, Haldorsen T, Aasland O G, Tyssen R, Vaglum P, Ekeberg O. Suicide rates according to education with a particular focus on physicians in Norway 1960-2000. Psychol Med. 2005 Jun;35(6):873-80.

14. Skegg K, Firth H, Gray A, Cox B. Suicide by occupation: does access to means increase the risk? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010 May;44(5):429-34.

15. Stallones L, Doenges T, Dik BJ, Valley MA. Occupation and suicide: Colorado, 2004-2006. Am J Ind Med. 2013 Nov;56(11):1290-5.

16. Hawton K, Agerbo E, Simkin S, Platt B, Mellanby RJ. Risk of suicide in medical and related occupational groups: a national study based on Danish case population- based registers. J Affect Disord. 2011 Nov;134(1-3):320-6.

17. Agerbo E, Gunnell D, Bonde JP, Mortensen PB, Nordentoft M. Suicide and occupation: the impact of socio-economic, demographic and psychiatric differences. Psychol Med. 2007 Aug;37(8):1131-40.

18. Kolves K, De Leo D. Suicide in medical doctors and nurses: an analysis of the queensland suicide register. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013 Nov;201(11):987-90.

19. Austin AE, Van den Heuvel C, and Byard W R. Physician Suicide. J Forensic Sci. 2013 Jan;58 Suppl 1:S91-3.

20. Gold K J, Sen A, M.S, Schwenk TL. Details on suicide among US physicians: data from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013 Jan- Feb;35(1): 45-49.

21. Petersen M R and Burnett C A. The suicide mortality of working physicians and dentists. Occup Med. 2008;58:25-29.

22. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Dyrbye L, Bechamps G, Russell T, Satele D et al. Suicidal Ideation Among American Surgeons. Arch Surg. 2011;146(1):54-62.

23. Lindfors P M, Meretoja O A, Luukkonen R A, Elovainio M J and Leino T J. Suicidality among Finnish anaesthesiologists. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2009;53:1027-1035.

24. Fridner A, Belkic K, Marini M, Minucci D, Pavan L, Schenck-Gustafsson K. Survey on recent suicidal ideation among female university hospital physicians in Sweden and Italy (the HOUPE study): crosssectional associations with work stressors. Gend Med. 2009 Apr;6(1):314-28.

25. Fridner A, Belkić. K, Minucci D, Pavan L, Marini M, Pingel B et al. Work environment and recent suicidal thoughts among male university hospital physicians in Sweden and Italy: the health and organization among university hospital physicians in Europe (HOUPE) study. Gend Med. 2011 Aug;8(4):269-79.

26. Rosta J and Aasland O G. Changes in the lifetime prevalence of suicidal feelings and thoughts among Norwegian doctors from 2000 to 2010: a longitudinal study based on national samples. BMC Psychiatry 2013;13:322.

27. Tomás-Sábado J, Maynegre-Santaulària M, Pérez-Bartolomé M, Alsina-Rodríguez M Quinta-Barber R, Granell-Navas S. Síndrome de burnout y riesgo suicida en enfermeras de atención primaria. Enferm. Clín. 2010 May- Jun;20(3):173-178.

28. Van der Heijden F, Dillingh G, Bakker A, Prins J. Suicidal thoughts among medical residents with burnout. Arch Suicide Res. 2008;12(4):344-6.

29. Fridner A, Belkić. K, Marinif M, Marie Gustafsson Sendéna, Schenck-Gustafssonb K. Why don't academic physicians seek needed professional help for psychological distress? Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13626.

30. WHO (2012). Mental Health Action Plan Europe. Risks to mental health: an overview of vulnerabilities and risk factors. http://www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap/risks_to_mental_health_EN_27_08_12.pdf.

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Miriam Cano Langreo,

Servicio Salud Laboral. Hospital Clínico San Carlos.

Calle Profesor Martín Lagos S/N,

Correo electrónico: mirian.cano@salud.madrid.org.

Teléfono: 913303431 Fax 913303431

Recibido: 23-01-14

Aceptado: 24-02-14

1. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Nota de prensa, defunciones según la causa de muerte año 2010. 20 Marzo 2012. http://www.ine.es/prensa/prensa.htm. Consultado el 15 de enero de 2014. [ Links ]

2. Pagina web, Prevención del Suicidio. Departamento de Psiquiatría Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. http://www.prevencionsuicidio.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=93&Itemid=151. Consultado el 15 de enero de 2014. [ Links ]

3. Aasland OG, Hem E, Haldorsen T, Ekeberg Ø. Mortality among Norwegian doctors 1960-2000. BMC Public Health 2011 Mar 22;11:173. [ Links ]

4. Shang TF, Chen PC and Wang JD. Mortality of doctors in Taiwan. Occup Med (Lond). 2011 Jan;61(1):29-32. [ Links ]

5. Torre DM, Wang NY, Meoni LA, Young JH, Klag MJ, Ford DE. Suicide compared to other causes of mortality in physicians. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2005 Apr;35(2):146-53. [ Links ]

6. Hawton K, Clements A, Sakarovitch C, Simkin S, Deeks JJ. Suicide in doctors: a study of risk according to gender, seniority and specialty in medical practitioners in England and Wales, 1979-1995. J Epidemiol Community Health 2001 May;55(5):296-300. [ Links ]

7. Lindeman S, Laara E, Hakko H, Lonngvist J. A sistematic review on Gender-specific suicide mortality in medical doctors. Br J Psychiatry 1996 Mar; 168 (3): 274-9. [ Links ]

8. Lagro-Janssen AL, Luijs HD. Suicide in female and male physicians. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2008 Oct 4; 152(40): 2177-81. [ Links ]

9. Schernhammer ES, Colditz GA: Suicide rates among physicians: a quantitative and gender assessment (meta-analysis). Am J Psychiatry 2004 Dec;161 (12): 2295-302. [ Links ]

10. Mingote J C, Crespo D, Hernández M, Navío M, Rodrígo C. Prevención del suicidio en médicos. Med Segur Trab (Internet) 2013; 59 (231) 176-204. [ Links ]

11. Hawton K, Vislise lL.Suicide in nurses. Suicide Life Threat Behav.1999; 29 (1):86-95. [ Links ]

12. Gagné P, Moamai J, and Bourget D. Psychopathology and Suicide among Quebec Physicians: A Nested Case Control Study. Depress Res Treat. 2011;2011:936327. [ Links ]

13. Hem E, Haldorsen T, Aasland O G, Tyssen R, Vaglum P, Ekeberg O. Suicide rates according to education with a particular focus on physicians in Norway 1960-2000. Psychol Med. 2005 Jun;35(6):873-80. [ Links ]

14. Skegg K, Firth H, Gray A, Cox B. Suicide by occupation: does access to means increase the risk? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010 May;44(5):429-34. [ Links ]

15. Stallones L, Doenges T, Dik BJ, Valley MA. Occupation and suicide: Colorado, 2004-2006. Am J Ind Med. 2013 Nov;56(11):1290-5. [ Links ]

16. Hawton K, Agerbo E, Simkin S, Platt B, Mellanby RJ. Risk of suicide in medical and related occupational groups: a national study based on Danish case population-based registers. J Affect Disord. 2011 Nov;134(1-3):320-6. [ Links ]

17. Agerbo E, Gunnell D, Bonde JP, Mortensen PB, Nordentoft M. Suicide and occupation: the impact of socio-economic, demographic and psychiatric differences. Psychol Med. 2007 Aug;37(8):1131-40. [ Links ]

18. Kolves K, De Leo D. Suicide in medical doctors and nurses: an analysis of the queensland suicide register. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013 Nov;201(11):987-90. [ Links ]

19. Austin AE, Van den Heuvel C, and Byard W R. Physician Suicide. J Forensic Sci. 2013 Jan;58 Suppl 1:S91-3. [ Links ]

20. Gold K J, Sen A, M.S, Schwenk TL. Details on suicide among US physicians: data from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013 Jan-Feb;35(1): 45-49. [ Links ]

21. Petersen M R and Burnett C A. The suicide mortality of working physicians and dentists. Occup Med. 2008;58:25-29. [ Links ]

22. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Dyrbye L, Bechamps G, Russell T, Satele D et al. Suicidal Ideation Among American Surgeons. Arch Surg. 2011;146(1):54-62. [ Links ]

23. Lindfors P M, Meretoja O A, Luukkonen R A, Elovainio M J and Leino T J. Suicidality among Finnish anaesthesiologists. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2009;53:1027-1035. [ Links ]

24. Fridner A, Belkic K, Marini M, Minucci D, Pavan L, Schenck-Gustafsson K. Survey on recent suicidal ideation among female university hospital physicians in Sweden and Italy (the HOUPE study): cross-sectional associations with work stressors. Gend Med. 2009 Apr;6(1):314-28. [ Links ]

25. Fridner A, Belkić K, Minucci D, Pavan L, Marini M, Pingel B et al. Work environment and recent suicidal thoughts among male university hospital physicians in Sweden and Italy: the health and organization among university hospital physicians in Europe (HOUPE) study. Gend Med. 2011 Aug;8(4):269-79. [ Links ]

26. Rosta J and Aasland O G. Changes in the lifetime prevalence of suicidal feelings and thoughts among Norwegian doctors from 2000 to 2010: a longitudinal study based on national samples. BMC Psychiatry 2013;13:322. [ Links ]

27. Tomás-Sábado J, Maynegre-Santaulària M, Pérez-Bartolomé M, Alsina-Rodríguez M Quinta-Barber R, Granell-Navas S. Síndrome de burnout y riesgo suicida en enfermeras de atención primaria. Enferm. Clín. 2010 May-Jun;20(3):173-178. [ Links ]

28. Van der Heijden F, Dillingh G, Bakker A, Prins J. Suicidal thoughts among medical residents with burnout. Arch Suicide Res. 2008;12(4):344-6. [ Links ]

29. Fridner A, Belkić K, Marinif M, Marie Gustafsson Sendéna, Schenck-Gustafssonb K. Why don't academic physicians seek needed professional help for psychological distress? Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13626. [ Links ]

30. WHO (2012). Mental Health Action Plan Europe. Risks to mental health: an overview of vulnerabilities and risk factors. [ Links ]

31. http://www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap/risks_to_mental_health_EN_27_08_12.pdf. Consultado el 10 de Diciembre de 2013. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en