Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.102 no.6 Madrid jun. 2010

Corelation among clinical, biochemical and tomographic criteria in order to evaluate the severity in acute pancreatitis

Correlación entre criterios clínicos, bioquímicos y tomográficos para evaluar la gravedad de la pancreatitis aguda

L. A. Lujano-Nicolás1, J. L. Pérez-Hernández2, E. G. Durán-Pérez3 and A. E. Serralde-Zúñiga4

1Service of Gastroenterology. Hospital General de México.

2Service of Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology. Postgraduate Course of the Universidad Autónoma de México.

Services of 3Internal Medicine and 4Clinical Nutrition. Hospital General de México. México

To all the Gastroenterology medical staff of Mexico's General Hospital for their invaluable support.

ABSTRACT

Background: the acute pancreatitis is an inflammatory process that may involve peripancreatic tissue and distant organs. According to the Atlanta criteria, in 10 to 20% of the patients the disease is severe. Nowadays there are different clinical and biochemical severity scales such as the Ranson, APACHE-II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation) and hematocrit, which have discrepancies when being compared to tomographic scales such as the Balthazar. There exist few studies that correlate these parameters.

Objective: to evaluate the severity of the acute pancreatitis according to the Ranson, APACHE-II and serous hematocrit criteria at the moment of admission of the patient and correlate these scales with the local pancreatic complications according to the Balthazar classification.

Patients and method: retrospective, observational and analytic study. There were included patients of any gender above the age of 18, with diagnosis of acute pancreatitis of any etiology, who had performed an abdominal tomography 72 hours after the beginning of the clinical condition in order to stage the pancreatic damage. The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis was established with 2 of the 3 following criteria: a) characteristic abdominal pain; b) uprising of the amylase and/or lipase more than 3 times above the superior normal limit; and c) characteristic finds of acute pancreatitis in the computed tomography. In order to make the correlation, the Pearson or the Spearman tests were used according to the distribution of the variables.

Results: there were included 28 patients (21 masculine, 75%). The most frequent etiology was due to alcohol (53.6%, bile (21.4%) and hypertriglyceridemia (17.9%). The age average was 38.1 years old. Fifty per cent of the patients had acute severe pancreatitis according to the Atlanta criteria. Of the patients with APACHE-II less than 8 points, 62.5% were classified according to the Balthazar tomographic scale as D or E degree. Ninety-two point nine per cent of the patients had less than 3 Ranson criteria of which 57.6% got D or E degree. Fifty-seven per cent of the patients with hematocrit value lower than 44% got D and E Balthazar degree, and 64.2% of the patients with hematocrit above 44% got D and E degree.

The Pearson correlation (PC) for APACHE-II and Ranson p = 0.013 of 0.476 PC for APACHE-II and Balthazar p = 0.367 of 0.476 and Spearman´s correlation p = 0.460 PC for APACHE-II and hematocrit p = 1.32 of 0.476.

Conclusions: there does not exist a good correlation between the seriousness scale of Ranson and APACHE-II with the tomographic Balthazar degrees, therefore it is more likely to find very ill patients with an A or B Balthazar and on the other hand patients with acute low pancreatitis with a D or E Balthazar.

Key words: Acute pancreatitis. APACHE-II. Ranson. Balthazar. Correlation.

RESUMEN

Antecedentes: la pancreatitis aguda es un proceso inflamatorio que puede involucrar tejido peripancreático y órganos distantes. En 10 a 20% de los pacientes la enfermedad es severa, según criterios de Atlanta. En la actualidad existen diferentes escalas clínicas y bioquímicas de severidad como la de Ranson, APACHE-II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation) y hematocrito, las cuales tienen discrepancias al compararlas con escalas tomográficas como la de Balthazar. Existen pocos estudios que correlacionen estos parámetros.

Objetivo: evaluar el grado de severidad de la pancreatitis aguda según criterios de Ranson, APACHE-II y hematocrito sérico al ingreso y correlacionar estas escalas con las complicaciones locales pancreáticas según la clasificación de Balthazar.

Pacientes y método: estudio retrospectivo, observacional y analítico. Se incluyeron pacientes mayores de 18 años de cualquier género, con diagnóstico de pancreatitis aguda de cualquier etiología, a los que se les realizó tomografía abdominal 72 horas posterior al inicio del cuadro clínico para estadificar el daño pancreático. El diagnóstico de pancreatitis aguda se estableció con 2 de 3 de los siguientes criterios: a) dolor abdominal característico; b) elevación de amilasa y/o lipasa a más de 3 veces por arriba del límite superior normal; y c) hallazgos característicos de pancreatitis aguda en la tomografía computada. Para correlación se utilizó la prueba de Pearson o la de Spearman según la distribución de las variables.

Resultados: se incluyeron 28 pacientes (21 masculinos, 75%). La etiología más frecuente fue por alcohol (53,6%), biliar (21,4%) e hipertrigliceridemia (17,9%). El promedio de edad fue de 38,1 años. El 50% de los pacientes cursaron con pancreatitis aguda severa según criterios de Atlanta. De los pacientes con APACHE-II menor a 8 puntos, el 62,5% según la escala tomográfica de Balthazar fueron clasificados como grado D o E. El 92,9% de los pacientes tuvieron menos de 3 criterios de Ranson de los cuales el 57,6% obtuvieron grado D o E. El 57% de los pacientes con valor de hematocrito menor a 44% obtuvieron grado D y E de Balthazar, y 64,2% de los pacientes con hematocrito mayor a 44%, obtuvieron grado D y E.

La correlación de Pearson (CP) para APACHE-II y Ranson p = 0,013 DE 0,476. CP para APACHE-II y Balthazar p = 0,367 DE 0,476 y correlación de Spearman’s p = 0,460. CP para APACHE-II y hematocrito p = 1,32 DE 0,476.

Conclusiones: no existe una buena correlación entre la escala de gravedad de Ranson y APACHE-II con los grados tomográficos de Balthazar, por lo cual es probable encontrar pacientes muy graves con un Balthazar A o B y en forma contraria pacientes con pancreatitis aguda leve con Balthazar D o E.

Palabras clave: Pancreatitis aguda. APACHE-II. Ranson. Balthazar. Correlación.

Introduction

The acute pancreatitis (AP) keeps on being one of the gastrointestinal pathologies with more incidence and that can unchain a significative mortality. Due to the seriousness that an AP condition implicates, different prognosis methods have been developed that can indicate us in a specific way the most likely outcome of each patient. During the daily clinical practice we often watch that the different severity scales have certain discrepancies. Until the present day there are few studies in literature that try to correlate these differences, this is why we have focused on the performance of a study in our hospital, trying to observe how frequent is the discrepancy between the severity degree and the tomographic finds according to the Balthazar classification.

According to the Atlanta Simposium, the acute pancreatitis (AP) was defined as an acute inflammatory process of the pancreas that may also involve peripancreatic tissue and/or distant organs. In 10 to 20% of the patients the disease is severe (1). The evaluation of the severity is one of the most important discussions on the AP handling. Approximately 15 to 20% of the patients with AP will develop severe disease and follow a prolonged course, typically on the stage of necrosis of the pancreatic parenchyma. Most series of the tertiary attention centers report mortality ranks of 5 to 15%, some being as high as 30%. Approximately half of the deaths happen during the first week due to multi-organ systemic failure (2-4).

The early severity predictors within the first 48 hours of the hospitalization include Ranson criteria (1) APACHE-II (1) punctuation, which by itself is not a reliable system of early seriousness detection during the first 24 hours and therefore must be used along with the other methods (5); and the serous hematrocrit > 44%, which must be quantified at the moment of admission and after 12 and 48 hours (1,4).

Recently the hemo-concentration has been identified as a strong risk factor and an early marker for necrotic pancreatitis and organ failure. An hematocrit > 44% at the moment of admission and a failure to diminish after 24 hours, represents a strong risk factor for the development of pancreatic necrosis (6), but not for organ failure. The hematocrit sensibility as a marker of acute necrotic pancreatitis is of 72% at the moment of admission and 94% after 24 hours, with a specificity of 83 and 69%, respectively (7,8).

The radiologic image is used to confirm or exclude the clinical diagnosis, establish the cause, evaluate the severity, detect complications and provide a guide for therapy (9). The computed tomography (CT) is recommended as the standard image diagnosis method for AP (10). For a better determination of the disease's severity, it must be performed 2 to 3 days after the beginning of the symptoms. The inflammation's severity can be graduated according to the Balthazar classification from A to E. In terms of organ failure and development of pancreatic necrosis, the most severe acute pancreatitis happen at the E Balthazar degree (1,2). Several studies show that pancreatic necrosis predicts the disease's seriousness with a 79-83% of sensibility, but with a low specificity of 42-65%. The clinical utility of the CT in the AP will be the verification of necrosis in those patients that show a priori clinical and/or biochemical criteria of severe AP (11).

The objective of this study was to correlate the severity degree of the acute pancreatitis according to the Ranson, APACHE-II criteria, and the determination of the serous hematocrit at the moment of admission, with the local pancreatic complications according to the tomographic Balthazar criteria, in order to give a better prognosis value to the tomographic finds in relation with the AP severity.

Material and methods

A retrospective, observational and analytic study was made. There were included files from patients of any gender admitted to the Gastroenterology Service of Mexico's General Hospital from January 2004 to December 2007, with AP diagnosis of any etiology. In order to see the staging of pancreatic damage, these patients had performed an abdominal tomography 72 hours after the beginning of the symptoms.

The AP diagnosis was performed to the patients that had at least 2 of the 3 following criteria: a) characteristic abdominal pain; b) amylase and/or lipase uprising 3 times above the superior normal limit; and c) characteristic finds of AP at the CT.

A recollection of demographic, clinical and laboratory data of gender, age, pancreatitis etiology, hematocrit at the moment of admission, pancreatitis severity according to the Ranson and APACHE-II criteria, organ failure, and/or local complications was made at the moment of admission. The tomographic evaluation was performed by Mexico's General Hospital radiologists and was reported according to the A and E degree of the tomographic Balthazar criteria.

Central tendency measurements and dispersion for the quantitative variables were used; the frequencies are expressed in proportion terms and written between parentheses. The Sperman coefficients of correlation were calculated in order to associate the different scales. The significancy level was considered < 0.05 (two tails). The SPSS version 12.0 statistic package was used. The data are presented in summary measurements: medians, proportions, and dispersion measurements.

Results

During the research period, there was an admission of 1,457 patients to the Gastroenterology Service of Mexico's General Hospital, in which 65 (4.4%) of the patients were diagnosed with AP. Of this 65 patients, 28 fulfilled the criteria of inclusion, the rest of the patients were excluded because either they had slight pancreatitis, didn't count with tomographic evaluation or were monitored on external consult.

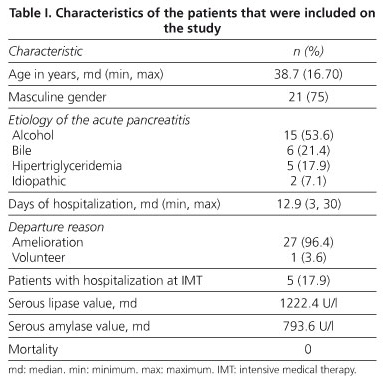

Twenty-one of the 28 (75%) were masculine. The main etiology was due to alcohol in 15 patients (53.6%), bile in 6 patients (21.4%), hypertriglyceridemia in 5 (17.9%) and idiopathic en 2 (7.1%). The age average was 38.1 years old with a rank of 18 to 60 years. The characteristics of the patients that were included on the study are shown on table I.

In table II, we can observe the characteristics of the patients according to the severity markers.

As it is shown in table III, it was documented that according to the tomographic Balthazar classification most of the patients with less punctuation of APACHE-II had more advanced tomographic degrees. In relation to the Ranson criteria, 57.6% of the patients with Ranson < 3 had D and E Balthazar degrees, which highlights a poor correlation between the Ranson value and the Balthazar tomographic degree. Concerning the hematocrit value, 57 and 64.2% of the patients with hematocrit < 44 and ≥ 44%, respectively, had D and E Balthazar degrees.

According to the Balthazar tomographic degree and the AP severity of clinical and biochemical criteria, of the patients that were classified within slight disease, none was classified within the A Balthazar degree, 21.4% were within B degree, 21.4% within C degree, 14.2% within D degree and 50% of the patients were classified within E Balthazar degree (Table III).

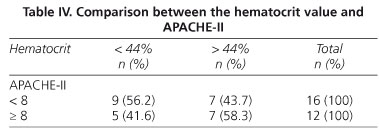

Comparing the hematocrit value with the APACHE-II, it was found that of the 16 patients with APACHE-II < 8 points, 56.2% had hematocrit < 44% and 43.7% had hematocrit ≥ 44% and of the 12 patients with APACHE-II ≥ 8, 58.3% had hematocrit ≥ 44% and 41.6% had hematocrit < 44% (Table IV).

We found a similar distribution between the slight and severe disease: 50% of the patients on each. The same was found taking into account the hematocrit level (50% of the patients had hematocrit > 44%).

Most of the patients had advanced classification Bal-thazar degrees (D and E in 67% of the patients), of which none had necrosis and therefore are not considered as a case of severe AP according to the Atlanta definition. When the observation was made in groups of slight and severe disease, we observed in both groups a larger percentage of patients with D and E Balthazar degrees (57 and 64%, respectively). Within the APACHE-II scale, both patients with punctuation < 8 and those with punctuation > 8 had advanced tomographic D and E degrees (58 and 62% respectively).

A poor correlation among the results of the different scales was documented. The correlation coefficients for the Balthazar scale were: 0.33 (NS) with APACHE, 0.25 (NS) with Ranson, 0.017 (NS) with hematocrit at the moment of admission, and (p < 0.001) for multiple organ failure.

Discussion

On this study we found that in our hospital service we have a low frequency of the disease. This maybe explained because it is a third level concentration center in which most of the AP patients are looked after in second level centers, therefore our results cannot be extrapolated to the population in general; it would be important to perform this analysis on these kind of attention centers.

It is proved that we can have patients who are classified with slight disease by means of the Ranson, APACHE-II or hematocrit criteria, however while performing the computed tomography, we found advanced Balthazar degrees, which indicate us that these scales must not be the only parameter to be taken into account to make the decision of performing or not this radiologic study in patients with slight acute pancreatitis. It must be pointed out that the optimal time to perform the tomographic study is 48 to 72 hours after the symptomatology has begun. The previous statement was carried out in all of our patients. If the CT is performed before this period, the results may be lower Balthazar degrees.

As it is pointed in some studies, the APACHE-II scale at the moment of admission is not to be trusted to neither diagnose pancreatic necrosis nor severe pancreatitis (12). It has been proved that the free intraperitoneal fluid and peripancreatic fat finds are associated with worse results (13). The best method to point out pancreatic necrosis is the CT; an indicative of it may be an hematocrit level > 44%. The previous statement takes relevance due to the fact that our study points out that there is no correlation between the Balthazar degree and the hematocrit level, therefore it is essential to perform the CT in order to point out advanced degrees of Balthazar with necrosis, independently of the hematocrit level and the Ranson and APACHE-II scales.

An important consideration was the impossibility to correlate the tomographic finds with the serum concentration of reactive C proteins, which is considered until the present moment the best prognosis indicator of AP. It was not possible on our second study to measure it on all of the patients, but in a posterior study it would be of great importance to correlate these parameters in order to look for a better indicator to make the decision of performing or not a tomographic study in patients with slight AP.

The number of patients of this study does not allow us to conclude in a categorical way the absence of correlation between the tomographic Balthazar finds and the clinical and biochemical scales previously mentioned, how-ever it encourages us to carry on with this research.

It can be suggested that there does not exist a statistically meaningful correlation between the APACHE-II scale of seriousness and the advanced Balthazar degrees due to the report of a poor correlation between Pearson and Spearman's, therefore it is likely to find very ill patients with an A or B Balthazar and on the other hand patients with slight acute pancreatitis with D o E Balthazar.

We also performed the Balthazar and Ranson correlation in patients with advanced Balthazar degrees and Ranson criteria < 3, which proves that there is no correlation between Ranson and Balthazar criteria, showing similar finds on the hematocrit value. Therefore, to have or not an advanced Balthazar does not necessarily represent a serious pancreatic disease or a systemic inflammatory response, and on the other hand to have a slight disease by means of clinical and biochemical criteria does not mean a lower degree on the tomographic Balthazar classification.

Until this moment, there are needed higher prospective and multi-centric studies that correlate the tomographic with the clinical and biochemical scales. Within them, the measurement of reactive C protein must be taken into account. Let us hope that in a future we can point out our finds in a more concrete way.

References

1. Banks PA, Freeman ML. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 2379-400. [ Links ]

2. AGA Institute Medical Position Statement on Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2007; 132: 2019-21. [ Links ]

3. Sánchez M. Pancreatitis aguda. Rev Med Int Med Crit 2004; 1: 1-17. [ Links ]

4. AGA Institute Technical Review on Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2007; 132: 2022-44. [ Links ]

5. Proves P, Fabregat J, García Borobia FJ, Jorba R, Figueras J, Jaurrieta E, et al. Early onset of organ failure is the best predictor of mortality in acute pancreatitis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2004; 96: 705-13. [ Links ]

6. Dhiraj Y, Agarwal N, Pitchumoni C. A critical evaluation of laboratory tests in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97: 1309-18. [ Links ]

7. Lankisch PG, Mahlke R, Blum T, Bruns A, Bruns D, Maisonneuve P, et al. Hemoconcentration: an early marker of severe and/or necrotizing pancreatitis? A critical appraisal. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96: 2081-5. [ Links ]

8. Brown A, Orav J, Banks P. Hemoconcentration is an early marker for organ failure and necrotizing pancreatitis. Pancreas 2000; 4: 367-72. [ Links ]

9. Carroll JK, Herrick B, Gipson T, Lee SP. Acute pancreatitis: diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Am Fam Physician 2007; 75: 1513-20. [ Links ]

10. Pancreatic disease group, Chinese society of gastroenterology and Chinese medical association. Consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of acute pancreatitis. Chin J Dig Dis 2005; 6: 47-51. [ Links ]

11. Fernández CJ, Iglesias CY, Domínguez M. Estratificación del riesgo: marcadores bioquímicos y escalas pronósticas en la pancreatitis aguda. Med Intensiva 2003; 27: 93-100. [ Links ]

12. Lankisch PG, Warnecke B, Bruns D, Werner HM, Grossmann F, Struckmann K, et al. The APACHE-II score is unreliable to diagnose necrotizing pancreatitis on admission to hospital. Pancreas 2002; 3: 217-22. [ Links ]

13. UK Working Party on Acute Pancreatitis. UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut 2005; 54: 1-9. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Lujano Nicolás Leslye Asela.

Calle Balmis #148, colonia

Doctores, Delegación Cuauhtémoc, México D.F.

e-mail: leslye_lujano21@hotmail.com

Received: 04-11-09.

Accepted: 18-02-10.

texto en

texto en