Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.109 no.10 Madrid oct. 2017

https://dx.doi.org/10.17235/reed.2017.4959/2017

CASE REPORT

Use of self-expanding nitinol stents in the pediatric management of refractory esophageal caustic stenosis

Empleo de stents autoexpandibles de nitinol en el manejo pediátrico de la estenosis cáustica esofágica refractaria

Verónica Alonso1, Devicka Ojha2, Harsha Nalluri3 and Juan Carlos de-Agustín4

1Department of Pediatric Surgery. Hospital Virgen del Rocío. Sevilla, Spain.

2Department of Internal Medicine. Ohio State University Hospitals. Columbus, Ohio.

3Radiology Department. University of Cincinnati Medical Center. Cincinnati, Ohio.

4Department of Pediatric Surgery. Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón. Madrid, Spain

ABSTRACT

Background: The treatment of recurrent esophageal stricture secondary to the ingestion of a caustic agent is an arduous task. Self-expanding esophageal stents may be an alternative to repeated endoscopic esophageal dilations.

Case report: We present the case of a two-year-old male with a severe and long esophageal stricture successfully treated by the combination of dilations and stent placement. After five months of serial pneumatic dilations, three self-expanding nitinol stents internally coated with silicone were introduced through a gastrostomy, covering the entire esophagus. The procedure was performed under endoscopic and radiological guidance. Three months later, the treatment was repeated with a single stent. A new stenosis in the proximal esophagus required surgical resection, and anastomosis followed by two pneumatic dilations for five months resulted in longer intervals where the patient was asymptomatic.

Discussion: The results obtained were satisfactory, allowing the patient to conserve and use his own esophagus. However, this is a unique case and the optimal maintenance time and withdrawal time of the stent must be determined.

Key words: Pneumatic dilation. Caustic ingestion. Esophageal stenosis. Self-expanding stents.

RESUMEN

Introducción: el tratamiento de la estenosis esofágica recurrente secundaria a la ingesta de un cáustico supone una ardua tarea. Los stents esofágicos autoexpandibles pueden ser una alternativa a las dilataciones esofágicas endoscópicas repetidas.

Caso clínico: presentamos el caso de un varón de dos años de edad que presenta una estenosis esofágica severa de gran extensión tratada con éxito mediante la combinación de dilataciones y colocación de stents. Después de cinco meses de dilataciones neumáticas seriadas, se introdujeron a través de una gastrostomía tres stents autoexpandibles de nitinol recubiertos internamente de silicona, cubriendo todo el esófago. El procedimiento se realizó bajo control endoscópico y radiológico. Tres meses después fue necesario repetir el tratamiento con un único stent. Una nueva estenosis en esófago proximal necesitó resección quirúrgica y anastomosis seguida de dos dilataciones neumáticas con intervalos asintomáticos progresivamente más largos durante cinco meses.

Discusión: los resultados obtenidos son satisfactorios, ya que permiten al paciente conservar y utilizar su propio esófago. Sin embargo, este es un caso único y debe determinarse el tiempo óptimo de mantenimiento y el momento retirada del stent.

Palabras clave: Dilatación neumática. Ingesta cáustica. Estenosis esofágica. Stents autoexpandibles.

Introduction

The management of a caustic agent intake and its complications represent a challenge for digestive specialists and surgeons. It is most commonly observed in children between one and three years of age, of whom 60% are males. The ingestion of an acid (coagulation necrosis) or alkali/base (liquefying necrosis) is frequently accidental in these patients and has a high corrosive potential. The tissue destruction can have devastating consequences, including respiratory distress, esophageal and gastric perforations, septicemia and even death. In many cases, the formation of stenosis is inevitable and the risk of developing esophageal cancer is greater than in the general population (1).

Case Report

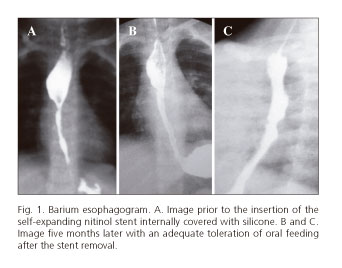

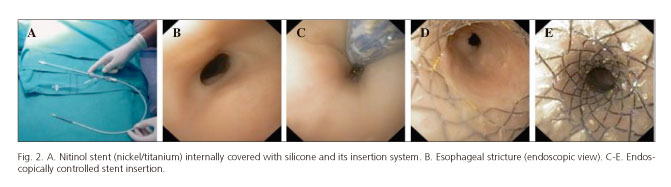

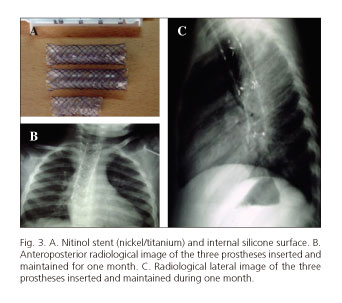

A two-year-old male was admitted to our center presenting with an esophageal stricture of three months evolution secondary to the accidental ingestion of a caustic product. The patient was referred to our institution with a gastrostomy and a nasogastric suture (stringing) that allowed for retrograde dilations. The barium esophagogram showed a long stenosis from the cricotracheal level to the lower third of the esophagus (Fig. 1A). A program of retrograde esophageal dilations was performed every two weeks without any improvement. Five months after the ingestion of the corrosive agent, three self-expanding nitinol stents covered with silicone (Stents MI Tech, Izasa) were internally placed through the gastrostomy, two of 16 x 60 mm and one of 16 x 40 mm. The most cranial one was placed first, introducing the others following a caudal direction and maintaining an overlapping distance of 1-2 cm to avoid their displacement (Figs. 2 and 3). This procedure achieved a complete dilation for one month.

The child reported pain as the only postoperative symptom and it disappeared spontaneously after four days. No migration or other short-term complications were observed. He tolerated his usual oral feeding adequately and was discharged with omeprazole (15 mg/24 hours orally) with a close follow-up in our outpatient clinic.

The stents were removed after four weeks and a dose of mitomycin (0.4 ml/kg) was sprayed onto the dilated area through the endoscope irrigator during the same procedure. Two residual stenosis measuring 1 cm were identified at the cricopharyngeal sphincter level and 3 cm above the cardias (Fig. 1B and C). The first one was identified during the previous endoscopic intervention. However, the placement of a stent in this region was impossible due to the generation of a tracheal compression. The distal esophageal stricture required another stent (16 x 40 mm), obtaining complete dilation after one month from its placement. Balloon dilations were performed at four weeks intervals, resulting in an elastic esophagus with a normal appearance of the mucosa. However, the aforementioned proximal esophageal stricture had a poor response and it was surgically resected using a laterocervical approach. Pneumatic dilations twice a month with progressively longer intervals were necessary for five months.

After two years of follow-up the patient was completely asymptomatic and with a healthy macroscopic aspect of the esophageal mucosa that was assessed by an endoscopic exam and a barium esophagogram.

Discussion

The intake of an alkali agent usually affects the natural esophageal constrictions and generally produces more tissue damage than acids (2). The gold standard treatment of esophageal strictures is dilation, with a success rate of 58-96% (3). Better results have been reported in patients with esophageal atresia compared to those with peptic or caustic stenosis. One to 15 dilations are required to treat symptomatic stenosis and perforation is the most serious and potentially fatal complication, with an incidence of 0.1-0.4% (4).

Mitomycin is an antibiotic produced by Streptomyces caespitosus that has antineoplastic properties and also acts as an antiproliferative agent. Its use is very promising, with greater asymptomatic intervals achieved after each dilation (5). In our case, we have used only one single dose. However a total of five doses is currently recommended by other authors; therefore, we cannot attribute its effectiveness to the success of the treatment in this patient.

The temporary use of non-metallic expandable stents may be effective in the management of benign refractory esophageal strictures when medical treatments and other endoscopic methods (pneumatic dilation) fail. Commercially available esophageal stents are generally inappropriate for pediatric patients because of their large size. Therefore, custom dynamic stents (6) as well as off-label airway stents (7) have been used. Neither the time that the stent should remain in the esophagus nor the withdrawal time have been clearly established, with a variable range of 4-6 weeks. Despite a very minimal number of pediatric studies, the therapeutic success rate of stenting is 50-85% for benign refractory esophageal strictures (5). Self-expanding plastic stents (SEPS) have better long-term outcomes in children (unlike adults) but a greater tendency for migration. This complication is less common with self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) and nitinol stents, but these are more traumatic during the extraction procedure (8).

According to data published of adult studies, fully covered SEMS may be able to overcome the existing problems related to partially or completely uncovered SEMS such as bleeding, fistulae, recurrent or newly occurring stenosis and erosion. Although biodegradable stents are still associated with migration and the recurrence of stenosis and aberrant tissue growth as complications, preliminary data in adults show that they could provide a valuable alternative to SEPS and SEMS (9).

In our patient, self-expanding nitinol stents were covered with silicone that was initially designed for the dilation of tracheal stenosis. The main reasons for our choice were their advanced technical design and better outcomes in adults. The placement of three instead of one was due to the absence of an appropriate length. New dilations were required after their placement but with longer asymptomatic periods. Even in the presence of refractory stenosis, the use of stents allowed the adequate and necessary tissue regeneration for the surgical resection and anastomosis, which otherwise is very difficult and unsafe with such a damaged tissue.

Conclusions

The use of stents is a very frequent treatment of esophageal stricture in adult patients. A small amount of case reports describe this therapy for children with benign stenosis who did not respond to standard dilations.

Our team has successfully treated a severe esophageal stricture in a two-year-old patient via the use of self-expanding nitinol stents coated with silicone and intercalated pneumatic dilations. We recommend endoscopic and radiological guidance, which are essential for a precise positioning. The results obtained are promising, although the optimal maintenance and removal time have to be determined.

References

1. Han Y, Cheng QS, Li XF, et al. Surgical management of esophageal strictures after caustic burns: A 30 years of experience. World J Gastroenterol 2004;10(19):2846-9. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i19.2846. [ Links ]

2. Contini S, Swarray-Deen A, Scarpignato C. Oesophageal corrosive injuries in children: A forgotten social and health challenge in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 2009;87(12):950-4. DOI: 10.2471/BLT.08.058065. [ Links ]

3. Michaud L, Gottrand F. Anastomotic strictures: Conservative treatment. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2011;52(Suppl 1):S18-9. DOI: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182105ad1. [ Links ]

4. Siersema PD, De Wijerslooth LRH. Dilatation of refractory benign esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;70:1000-12. DOI: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.07.004. [ Links ]

5. Lévesque D, Baird R, Laberge JM. Refractory strictures post-esophageal atresia repair: What are the alternatives? Dis Esophagus 2013;26(4):382-7. DOI: 10.1111/dote.12047. [ Links ]

6. Foschia F1, De Angelis P, Torroni F, et al. Custom dynamic stent for esophageal strictures in children. J Pediatr Surg 2011;46(5):848-53. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.02.014. [ Links ]

7. Rico FR, Panzer AM, Krooros K, et al. Use of polyflex airway stent in the treatment of perforated esophageal stricture in an infant: A case report. J Pediatr Surg 2007;42(7):E5-E8. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.04.027. [ Links ]

8. Broto J, Asensio M, Gil Vernet JM. Results of a new technique in the treatment of severe esophageal stenosis in children: Polyflex stents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2003;37(2):203-6. DOI: 10.1097/00005176-200308000-00024. [ Links ]

9. Hindy P, Hong J, Lam-Tsai Y, et al. A Comprehensive review of esophageal stents. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY) 2012; 8(8):526-34. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Verónica Alonso.

Department of Pediatric Surgery.

Hospital Virgen del Rocío.

Av. Manuel Siurot, s/n. 41013 Sevilla, Spain

e-mail: alonso.veronika@gmail.com

Received: 30-03-2017

Accepted: 04-05-2017

texto en

texto en