Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.110 no.5 Madrid may. 2018

https://dx.doi.org/10.17235/reed.2018.5331/2017

ORIGINAL PAPERS

Using the internet to evaluate the opinion of patients with inflammatorybowel disease with regard to the available information

1Departamento de Medicina, Dermatología y Toxicología. Facultad de Medicina. Universidad de Valladolid. Valladolid, España

2Servicio de Aparato Digestivo. Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid. Valladolid, España

INTRODUCTION

The doctor-patient relationship has changed during the last few decades. This has evolved from a dependent relationship in which the patient accepts the doctors' opinions to a relationship in which the patient is informed, gives opinions and shares or disputes the decisions of the doctor. For this relationship to work well, in addition to a minimum understanding on both parts, the patient must have adequate information with regard to the situation. However, this understanding depends on the limits of communication and determines the points of view of the physician and patient with regard to the disease and its implications. This has been recently shown in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in Spain 1. Actually, the peculiarities and organization of the Spanish health-care services, and perhaps our physician capacities, do not allow a proper evaluation of the needs of every patient that attends the clinic. This is important in order to establish a satisfactory doctor-patient relationship and provide the patients with all the information that they deserve.

In spite of the omnipresence of the internet, doctors are still considered to be the patients' most important source of information. Several studies have shown that the internet, with its advantages and disadvantages, is the main alternative source of patient information. The sites consulted can include general information, marketing, or be general or specific medical consultation websites. There are also blogs, patient association websites or social network sites such as Facebook or Twitter 2,3,4.

Quality of life of IBD patients correlates with their worries and concerns 5,6 and therefore, adapting information to the patient is of great interest. The objectives of the study were to determine how patients felt about the degree of available information and the information that their usual doctors (specialists) provided them. We also determined how patients used the internet as a resource and identified factors that predicted a sense of being better informed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

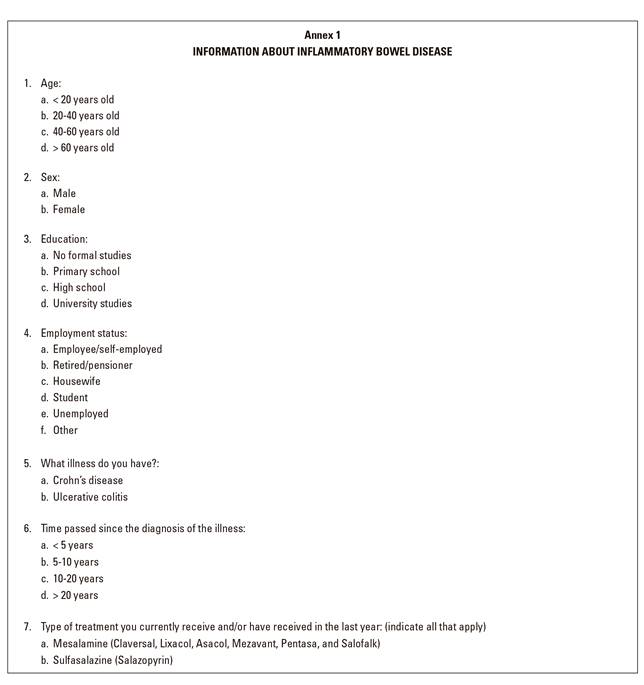

A 39-item survey was designed that was aimed at patients with IBD (Annex 1). The survey evaluated the information that the patients had available, which was scored on a scale from 1 to 10 (1 being the worst and 10, the best). Furthermore, their opinion of the information provided by the specialist was evaluated as poor, adequate, good and very good. The survey also covered demographic information such as age, sex, educational level and work status, as well as clinical data such as IBD type, disease course, assessment of IBD severity in the last year, treatment type, anxiety level according to the of HAD scale 7,8, how the information influenced treatment adherence and the use of "alternative medicine". Other related information sources on IBD aspects, the use and influence of the internet and pages consulted were also assessed.

GoogleForms (https://www.google.com/intl/es/forms/about/) was used to design both the survey itself and a page about the study objectives. The Valladolid and León (Spain) province chapters of the Association for Patients with Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (ACCU is the acronym in Spanish) emailed the forms to their members on the 19th of December 2016. The survey and the objectives page were also uploaded to three internet forums for patients with IBD on the 30th of December 2016. In addition, they were uploaded on the 11th of January 2017 to the "Crohn's and UC, the C Team (Facebook Group United by IBD)" ("Crohn's & UC") Facebook page after contacting the site administrator. This website was created in Spain on the 8th of February 2011, the official language is Spanish and it has 4,596 members.

Returning the survey to us was considered as acceptance to participate in the study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínico Universitario in Valladolid (TFG-599). Replies to the survey questions were analyzed and expressed using absolute and relative frequencies. Scale scores were expressed as a mean and interquartile range (IQR). The Chi-squared test was used to analyze the association between discrete variables. Uni- and multivariate binary regression analyses were used for predictive factors to rate the information with scores of 8 or more points on a scale of 1 to 10 (minimum to maximum). The OR and CI values were calculated. Statistical significance was set to p = 0.05.

RESULTS

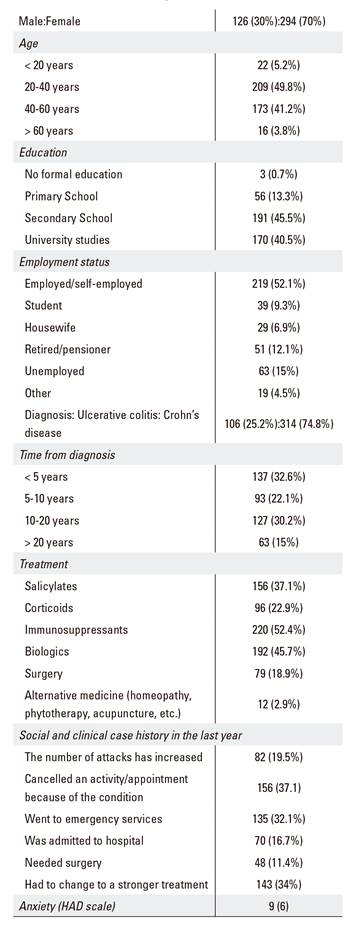

Forty-four replies were received from the surveys disseminated to the patient associations and the three forums for patients with IBD. After uploading the survey to the "Crohn's & UC" Facebook page, 376 replies were received in five days. Therefore, a total of 420 surveys were returned, 70% of which were answered by women. Less than 4% of the patients were over 60 years old and 95% had secondary or university studies. Patients with Crohn's disease (CD) predominated over patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) (74% and 25%, respectively). Time from diagnosis varied considerably, between five and 20 years. With regard to treatment, 52% of the patients received immunosuppressants, 45% received biological drugs and 22% corticoids, and 20% had undergone surgery at least once. Almost one in five patients indicated that they had experienced a flare-up in the last year and almost one in three had to go to the ER or cancel an appointment or commitment due to the illness. Only 3% of patients followed an alternative treatment such as acupuncture, homeopathy or phytotherapy. Table 1 presents the patient characteristics in detail.

Patients rated the information available to them with a mean score of 8 (IQR 2) on a scale from 1 (minimum score) to 10 (maximum). Specialist-provided information was considered as good or very good by 71% of patients. However, only 38% of patients considered that the information received at diagnosis was adequate and less than 30% said that there were no doubts after seeing the specialist. Almost a fourth of patients acknowledged that they had thought about stopping treatment due to a lack of information. When patients scored their available information with 8 or more points, they thought about stopping treatment due to a lack of information less frequently than if the score was less than 8 (18.6% vs 30.7%, p = 0.001). Patient evaluation of specialist-provided information (poor, adequate, good or very good) was also associated with thinking about stopping treatment due to a lack of information in 67.7%, 35.4%, 18.6% and 14.1% (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1) of cases and linked to alternative medical treatments such as homeopathy, acupuncture or phytotherapy in 14.3%, 2.1%, 2.5% and 2.1%, respectively (p = 0.015). Nearly half the patients considered that being better informed was associated with having fewer flare-ups and most patients felt that society needed to be better informed about IBD. Responses to questions related to the evaluation of the patient-available information and its importance are shown in table 2.

Fig. 1 Association between the degree of information from the doctor and adherence to treatment (Chi-squared test, p < 0.001; linear by linear association test, p < 0.001).

Table 2 Assessment of the information the patients had available and the importance given to the information

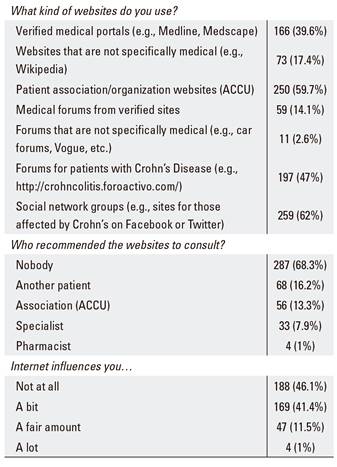

The three aspects for which patients sought information most frequently were IBD complications, IBD evolution and dietary aspects. Information sources considered to be useful were the specialist (87%), patient associations (ACCU) (55%), other patients (54%) and the internet (28%). A fourth of patients indicated that they did not consult the internet. Patients who used the internet conducted searches after seeing the specialist (38%) or both before and after the visit (25%). The websites consulted most frequently were specific pages in social networks such as Facebook (62%), patient association websites (59%) and patient forums (47%). Specialists and patient associations rarely recommend webpages about IBD to patients. Only 11% of patients considered that the internet had any significant influence in their decisions. The internet had no influence in 20%, 32%, 42% and 65% of patients poorly, adequately, well or very well informed by their doctor, respectively (p < 0,001) (Fig. 2). Table 3 shows the responses to questions about the aspects for which information was sought, as well as the patient information sources.

Fig. 2 Association between the quality of information from the doctor and internet influence (Chi-squared test, p < 0.001; linear by linear association test, p < 0.001).

The predictive factors for a score ≥ 8 (from 1 to 10) for the patient-available information by univariate analysis were age, OR 1.578 (CI 1.158-2150), p = 0.004; education level, OR 1.513 (CI 1.144-2.002), p = 0.004; time from diagnosis, OR 1.432 (CI 1.184-1.731), p < 0.001; treatment with salicylates, OR 0.553 (CI 0.367-0.833), p = 0.005; treatment with biologicals, OR 1.701 (CI 1.141-2.534), p = 0.009; anxiety, OR 0.951 (CI 0.908-0.931), p = 0.031; and specialist-provided information, OR 3.399, (CI 2.561-4.512), p < 0.001. Independent predictive factors identified via the multivariate analysis that included the univariate-analysis predictive factors as well as sex were age, OR 1.539 (CI 1.047-2.261), p = 0.028; education level, OR 1.544 (CI 1.110-2.147), p = 0.010; time from diagnosis, OR 1.267 (CI 1.003-1.601), p = 0.047; and information from the specialist, OR 3.262 (CI 2.425-4.388), p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

According to our data, the patients consider themselves acceptably well informed about their IBD condition as the variable about available information scored 8 or more (from 0 to 10). Information and knowledge have been linked in several studies with factors related to quality of life 9 as well as healthcare and efficacy aspects 10,11. However, it is necessary to distinguish between the patient's perception of being better or worse informed and the true knowledge of the patient, which can be measured using different scales 12,13,14.

The fact that access to the survey and sending the replies was via the internet (and a large proportion of patients that subscribed to the Facebook page) implies that the patients analyzed had at least an average internet knowledge and regularly used internet and social networks. The majority of the 420 patients included in the study were female, had secondary or university studies, were younger than 60 years old and half of them received either immunosuppressant or biological drug treatment. A poorer quality of life in females has been reported previously 15. Women also tend to worry to a higher degree with regard to different aspects of IBD 16 and this could explain their higher participation rate in the survey. Furthermore, social or healthcare spheres were also affected by IBD, 37% of cases had to cancel an arrangement or an activity due to their illness in the last year, 34% had to increase treatment, and 32% went to the emergency services at least once.

It is very encouraging that this study gained access to the patients and received their responses via a website (a Spanish website) in a social network such as Facebook.

This is a tool that should be explored and taken into consideration in the future. The advantages are obvious, such as obtaining patient responses quickly and easily. The limitations are also obvious: the bias in the selection of patients with specific characteristics, the truthfulness of the responses (inherent in questionnaires), and the impossibility to determine the patients' geographic location (there was no geographic reference in the survey).

The patients felt that they were well informed as they rated the information available to them with a score of 8 or more. This information seemed to come mainly from the specialist. Eighty-seven per cent of patients considered them to be the main source of useful information and most patients thought that the specialist-supplied information was good or very good. This probably reflects the good work of the IBD doctors in Spain. In 2004, a Spanish study reported that more than 80% of patients felt that they were well informed 17. Another Spanish study of 385 patients in Levante in 2008 also reported a 96% satisfaction rate with regard to information that came from the doctor 4. Other information sources viewed as useful were conversations with other patients, patient associations and the internet. Although, the frequency was lower than that described in a Swiss study 18 and a Spanish study from hospitals in Levante 4. A Canadian study with a lower number of recently diagnosed patients also reported the internet as the second most important source of information after doctors 2.

Although the information received score highly in our study, certain features that the specialists or healthcare institutions should improve have been identified. Marín-Jiménez et al. recently demonstrated some limitations with regard to the clinical management of psychological aspects and the impact on quality of life of the patients 1. Those highlighted in our study included the information that patients receive at diagnosis, as well as the information provided during standard specialist follow-up. Nearly 60% of our patients felt that the information provided when they were diagnosed was inadequate, a considerably higher percentage than the 24% described by Bernstein et al. described in Canada 2. Furthermore, 25% of our patients indicated that they were left with a lot of doubts after seeing the specialist. These data are consistent with other studies with regard to the information required by the patients about certain aspects of the illness (most likely because these aspects were infrequently addressed by their doctor), such as IBD causes, evolution and complications, and dietary considerations 17,19. In one of the aforementioned Spanish studies, patients requested labor rights and clinical trial information 4. According to Pittet et al., 18 the need for one type of information or another can vary depending on the phase of the disease course. Bernstein et al. recognized that giving a broad and substantial amount of information is very difficult in the clinic and prefer written information or web sites recommendations 2.

Information is important for the patients and the healthcare system. A greater risk of flare-up was thought to be linked to insufficient information by 48% of our patients. We noted that patients often search the internet before or after seeing their specialist and we also found a link between the perception of information quality and treatment adherence. In countries such as Switzerland, non-adherence is as high as 18% and low adherence is more common among patients that consider that the information available to them was insufficient 20,21. Information was also important in other circumstances for patients. They believe that social awareness should also be improved; over half of our patients have experienced an embarrassing or unfair situation related to their illness in the work environment or in a restaurant.

Multivariate analysis identified factors that independently predict whether patients consider themselves as better informed. Elderly patients (most patients were less than 60 years old), a longer time since IBD diagnosis, higher education level and cases that felt well informed by the specialist tended to view themselves as better informed. Univariate analysis also revealed a relationship with treatment. Patients who received mesalazine felt poorly informed, while patients under biologic treatment felt well informed. Obviously, this may be related to the time spent explaining the obligatory information for complex treatments. We also found via univariate analysis that anxiety was associated with the level of information considered as inadequate by the patient. The link between anxiety and information can be complicated. Patients who are very anxious may be more demanding with regard to information 18, and increased anxiety has been associated with worse information 9. However, it has also been shown that increased anxiety is linked to a greater knowledge of the illness 22 and we also saw that knowledge about different aspects of IBD increased concerns in patients and relatives 23.

Even though our contact with the patients for the survey was via the internet, 25% of cases indicated that they did not look for information about IBD on the internet. In addition, most of them said that information on the internet had little or no effect on them. Other studies have revealed that patients would like doctors or healthcare institutions to create websites where they can get information 24,25. The doctors' lack of interest in the internet is clear in our study; the specialists, pharmacists and patient associations make no effort to recommend one website or another to patients. This has far-reaching effects as the quality of websites varies significantly. In the USA, 60% of gastroenterologists recommend websites where their patients can obtain appropriate information 26. Spain has an excellent website created by professionals that provides information and makes things easier for patients (https://www.educainflamatoria.com). The Spanish Group for the Study of Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (GETECCU, Spanish acronym) and obviously ACCU Spain have a website where patients can obtain reliable information. In the United States and Canada, the Crohn's & Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA) website is most often consulted by cases in these countries 3,27. Commitment to the internet for informing patients and facilitating healthcare seems necessary. The "Constant-Care" from Denmark and Ireland has shown that remote clinical follow-up using the internet is feasible, reliable and efficient, and can reduce flare-ups and improve the quality of life of patients with UC 28. Other projects on the influence of technology in communication and information about IBD have identified other advantages of these methods 29. The fact that the vast majority of our survey responses were via a Facebook page is interesting. Social network pages are obviously what patients most commonly visit. In the United States, Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest and Twitter are most visited by patients with IBD 27. Doctors and healthcare institutions will probably have to accept their presence on Facebook and Twitter. Although there are advantages and drawbacks, this is necessary if we are to keep up with patient concerns and provide them with accurate and reliable information.

Our patients are satisfied with the information available and that provided by their specialist. However, there are some deficiencies that should be addressed, such as the information at the time of diagnosis and more extensive information for younger patients, those with a lower educational background and with less complicated disease presentations. There is room for improvement for healthcare professionals, healthcare institutions and medical societies to create or participate in websites. Furthermore, specialists need to recommend websites that patients could consult. These two practices would help to ensure that patients have access to accurate and reliable information.

BIBLIOGRAFÍA

1. Marín-Jiménez I, Gobbo Montoya M, Panadero A, et al. Management of the psychological impact of inflammatory bowel disease: perspective of doctors and patients - The ENMENTE Project. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23(9):1492-8. DOI: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001205 [ Links ]

2. Bernstein KI, Promislow S, Carr R, et al. Information needs and preferences of recently diagnosed patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17(2):590-8. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.21363 [ Links ]

3. Becker HM, Grigat D, Ghosh S, et al. Living with inflammatory bowel disease: a Crohn's and colitis Canada survey. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;29(2):77-84. DOI: 10.1155/2015/815820 [ Links ]

4. Catalan-Serra I, Huguet-Malaves JM, Mínguez M, et al. Information resources used by patients with inflammatory bowel disease: satisfaction, expectations and information gaps. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;38(6):355-63. DOI: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2014.09.003 [ Links ]

5. Stjernman H, Tysk C, Almer S, et al. Worries and concerns in a large unselected cohort of patients with Crohn's disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 2010;45(6):696-706. DOI: 10.3109/00365521003734141 [ Links ]

6. Jelsness-Jorgensen LP, Moum B, Bernklev T. Worries and concerns among inflammatory bowel disease patients followed prospectively over one year. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2011;2011:492034. DOI: 10.1155/2011/492034 [ Links ]

7. Snaith RP, Zigmond AS. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Br Medical Journal (Clin Res Ed) 1986;292(6516):344. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.292.6516.344 [ Links ]

8. Herrero MJ, Blanch J, Peri JM, et al. A validation study of the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) in a Spanish population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2003;25(4):277-83. DOI: 10.1016/S0163-8343(03)00043-4 [ Links ]

9. Moser G, Tillinger W, Sachs G, et al. Disease-related worries and concerns: a study on out-patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995;7(9):853-8. [ Links ]

10. Wardle RA, Mayberry JF. Patient knowledge in inflammatory bowel disease: the Crohn's and Colitis Knowledge Score. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;26(1):1-5. DOI: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328365d21a [ Links ]

11. Colombara F, Martinato M, Girardin G, et al. Higher levels of knowledge reduce health care costs in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21(3):615-22. DOI: 10.1097/MIB. 0000000000000304 [ Links ]

12. Jones SC, Gallacher B, Lobo AJ, et al. A patient knowledge questionnaire in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 1993;17(1):21-4. DOI: 10.1097/00004836-199307000-00007 [ Links ]

13. Eaden JA, Abrams K, Mayberry JF. The Crohn's and Colitis Knowledge Score: a test for measuring patient knowledge in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94(12):3560-6. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01536.x [ Links ]

14. Keegan D, McDermott E, Byrne K, et al. Development, validation and clinical assessment of a short questionnaire to assess disease-related knowledge in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Scand J Gastroenterol 2013;48(2):183-8. DOI: 10.3109/00365521.2012.744090 [ Links ]

15. Casellas F, López-Vivancos J, Casado A, et al. Factors affecting health related quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Qual Life Res 2002;11(8):775-81. DOI: 10.1023/A:1020841601110 [ Links ]

16. Berroa de la Rosa E, Mora Cuadrado N, Fernández Salazar L. The concerns of Spanish patients with inflammatory bowel disease as measured by the RFIPC questionnaire. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2017;109(3):196-201. DOI: 10.17235/reed.2017.4621/2016 [ Links ]

17. Casellas F, Fontanet G, Borruel N, et al. The opinion of patients with inflammatory bowel disease on healthcare received. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2004;96(3):174-84. DOI: 10.4321/S1130-01082004000300003 [ Links ]

18. Pittet V, Vaucher C, Maillard MH, et al. Information needs and concerns of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: what can we learn from participants in a bilingual clinical cohort? PloS ONE 2016;11(3):e0150620. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150620 [ Links ]

19. Wong S, Walker JR, Carr R, et al. The information needs and preferences of persons with longstanding inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Gastroenterol 2012;26(8):525-31. DOI: 10.1155/2012/735386 [ Links ]

20. Pittet V, Rogler G, Mottet C, et al. Patients' information-seeking activity is associated with treatment compliance in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Scand J Gastroenterol 2014;49(6):662-73. DOI: 10.3109/00365521.2014.896408 [ Links ]

21. De Castro ML, Sanromán L, Martín A, et al. Assessing medication adherence in inflammatory bowel diseases. A comparison between a self-administered scale and a pharmacy refill index. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2017;109(8):542-51. DOI: 10.17235/reed.2017.5137/2017 [ Links ]

22. Selinger CP, Eaden J, Selby W, et al. Patients' knowledge of pregnancy-related issues in inflammatory bowel disease and validation of a novel assessment tool ("CCPKnow"). Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012;36(1):57-63. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05130.x [ Links ]

23. Berroa E, Fernández-Salazar L, Rodríguez McCullough N, et al. Are worries and concerns information side effects? Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21(9):E22. DOI: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000539 [ Links ]

24. Panes J, De Lacy AM, Sans M, et al. Frequent internet use among Catalan patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;25(5):306-9. [ Links ]

25. Angelucci E, Orlando A, Ardizzone S, et al. Internet use among inflammatory bowel disease patients: an Italian multicenter survey. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;21(9):1036-41. DOI: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328321b112 [ Links ]

26. Nguyen DL, Rasheed S, Parekh NK. Patterns of Internet use by gastroenterologists in the management and education of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. South Med J 2014;107(5):320-3. DOI: 10.1097/SMJ.0000000000000107 [ Links ]

27. Reich J, Guo L, Hall J, et al. A survey of social media use and preferences in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22(11):2678-87. DOI: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000951 [ Links ]

28. Elkjaer M, Shuhaibar M, Burisch J, et al. E-health empowers patients with ulcerative colitis: a randomised controlled trial of the web-guided "Constant-care" approach. Gut 2010;59(12):1652-61. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2010. 220160 [ Links ]

29. Jackson BD, Gray K, Knowles SR, et al. E-health technologies in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. J Crohn's Colitis 2016;10(9): 1103-21. DOI: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw059 [ Links ]

Received: October 28, 2017; Accepted: January 24, 2018

texto en

texto en