Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial

versión On-line ISSN 2173-9161versión impresa ISSN 1130-0558

Rev Esp Cirug Oral y Maxilofac vol.30 no.1 Madrid ene./feb. 2008

Prevalence of cleft lip and palate and risk indicators: Study of the reference population of Felix Bulnes University Hospital, Santiago de Chile

Prevalencia de fisura labiopalatina e indicadores de riesgo: Estudio de la población atendida en el Hospital Clínico Félix Bulnes de Santiago de Chile*

G. Sepúlveda Troncoso1, H. Palomino Zúñiga2, J. Cortés Araya1-3

1 Docente. Departamento de Cirugía Bucal y Máxilofacial, Facultad de Odontología, Universidad de Chile.

2 Profesor Titular. Programa de Genética Humana, Instituto de Ciencias Biomédicas, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Chile.

3 Cirujano Máxilofacial. Unidad de Fisurados del Servicio de Cirugía Infantil, Hospital Clínico Félix Bulnes. Profesor Asociado del Departamento de Cirugía Bucal y Máxilofacial de la Facultad de Odontología de la Universidad de Chile.

*Trabajo realizado en la Unidad de Fisurados, Servicio de Cirugía Infantil, Hospital Clínico Félix Bulnes.

ABSTRACT

Introduction. The study of the prevalence of cleft lip and palate and the identification of risk groups helps to improve the treatment of this condition. Occurrence may be prevented by improving environmental conditions during pregnancy and ensuring early diagnosis, thus lessening the emotional impact on the family and reinforcing the early mother-child bond. The aim of this study was to improve prevention levels and thus enhance health resources.

Material and Method. The frequency of cleft lip and palate and its association with risk factors was studied in live births of the Felix Bulnes University Hospital in Santiago between January 1998 and June 2005. Maternal conditions and exposure to environmental agents associated with cleft lip and/or palate were examined.

Results. Out of a total of 36,041 births, 51 cases of cleft lip and palate were found, which yielded a rate of 1.42 x 1000 births.

Conclusions. Analysis of risk indicators identified: mothers under the age of 20 years, usually with their first pregnancy, a high degree of Amerindian admixture and family history positive for this malformation. Our study supports the multifactorial inheritance theory of susceptibility to cleft lip and palate.

Key words: Prevalence; Oral Clefts; Risk Factors.

RESUMEN

Introducción. El estudio de la prevalencia de fisuras labiopalatinas y la determinación de indicadores de riesgo ayuda a prevenir su ocurrencia mejorando las condiciones durante la concepción o gestación. También favorece diagnósticos precoces que atenúan el impacto emocional favoreciendo el apego madre-hijo y mejorando la respuesta materna al tratamiento. Ambas situaciones permiten optimizar y focalizar los recursos sanitarios disponibles.

Material y Método. Se determinó la incidencia de fisuras labiopalatinas y la asociación a factores de riesgo en los RNV beneficiarios del Hospital Clínico Félix Bulnes de Santiago de Chile entre enero del año 1998 y junio del 2005. Se estudió además condiciones y exposición maternas a agentes ambientales asociados a fisura labial y/o palatina.

Resultados. Sobre un total de 36.041 RNV consecutivos, se registraron 51 casos de fisurados, obteniéndose una tasa de 1,42 x 1000 RNV.

Conclusiones. Los indicadores de riesgo identificados correspondieron a edad materna menor a veinte años asociado al primer embarazo; alto grado de etnicidad amerindia e historia familiar positiva para este tipo de malformación. Nuestro estudio apoya la teoría de herencia multifactorial de la susceptibilidad a las fisuras labiopalatinas.

Palabras clave: Prevalencia; Fisuras faciales; Indicadores de riesgo.

Introduction

Cleft lip and/or palate are congenital malformations with a high prevalence in Chile. One case per 740 live births is estimated.1 The epidemiological dimensions of this condition make it a public health problem.

The cleft condition originates morphologic, functional, and emotional disorders in the patient that make social insertion difficult. The family, particularly the mother, is affected emotionally. This emotional effect begins at birth, when the mother receives the diagnosis and her grief affects her relation with her newborn. On the other hand, treatment of this condition involves considerable effort and expenses. Study of the etiology and identification of risk indicators in specific populations could improve therapeutic response. Improving the conditions of conception and/or gestation may prevent occurrence. Early diagnosis may be effective in attenuating the emotional impact on the mother and improving her bond with her infant and disposition toward and participation in treatment. Both goals seek to achieve prevention levels that allow health care resources to be targeted and optimized.

Evidence exists that certain genetic factors condition the appearance of cleft lip and/or palate. Numerous studies have sought specific genes,2-4 form of inheritance,5,6 and causes of ethnic differences.7,8 Teratogens have been identified that directly affect the embryo, such as drugs and toxins used in agriculture and industry.9-13 These noxa may also affect parental gametes and the resulting offspring. Maternal age and diseases during pregnancy seem to contribute to pathogenesis.14-17

The aim of the present study was to determine the prevalence of cleft lip and/or palate in the reference population of the Felix Bulnes University Hospital (Chile) and to identify risk indicators.

Material and method

We examined the records of 36,041 births, corresponding to all live births between January 1998 and June 2005 in Felix Bulnes University Hospital, Santinago (Chile). We detected 51 infants diagnosed as nonsyndromic cleft lip and/or palate. Another 24 cases referred by other centers were included in the analysis of variables, independently of birthplace. The history of the case infants and their mothers was obtained from medical records. Case infants with cleft lip and/or palate were each paired with a healthy newborn of the same sex born immediately after the case infant for the purpose of establishing a control group; information on the mother of the healthy infant was also analyzed.

The information was recorded on a specially designed card that included gender, date of birth, specific diagnosis, and blood group. The maternal history included age, pregnancy order, occurrence of malformations in relatives, parent consanguinity, and exposure to teratogens before and during pregnancy.

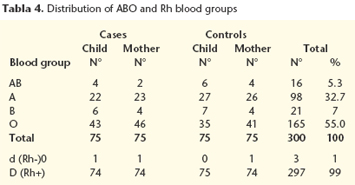

The ethnic admixture was assessed using the phenotypical frequencies of the ABO and Rh groups to establish the percentage of alleles of indigenous origin using Bernsteins method.18

The O allele of the ABO group and d allele of negative Rh factor were studied separately. Averages were calculated and expressed as the percentage admixture.

The information was processed and analyzed statistically to calculate frequencies and averages. Chi square analysis was used with qualitative variables.

Results

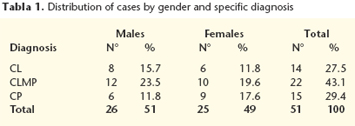

A total of 51 nonsyndromic cases were detected in a universe of 36,041 consecutive births between January 1998 and June 2005 in the study of prevalence of cleft lip and/or palate. The distribution by gender and diagnosis is shown in table I. Cleft lip with maxillopalatine cleft (CLMP) occurred in 43.1% of cases, isolated cleft palate (CP) in 29.4%, and isolated cleft lip (CL) in 27.5%. Within the CLMP group, 63.6% of cases were of the left side and only 9.1% on the right side. Six cases (27.3%) were bilateral. Among the cleft lips, 57.2% were on the left side, 35.7% on the right, and 7.1% were bilateral. CLMP and CL were both more prevalent in males, whereas CP was more prevalent in females. The overall prevalence of cleft lip and/or palate was 1.42 per 1000 live births. The distribution by gender disclosed no significant differences (Chi2 = 1.05; df = 2; p = 0.59).

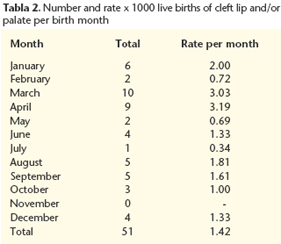

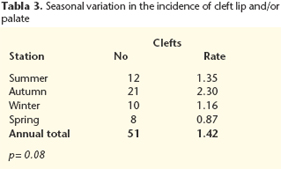

The number of infants with cleft lip and/or palate and rates per thousand, separated by birth month, are shown in Table II. The distribution by months was homogeneous except for a considerable increase in rates in March and April, to 3.03 and 3.19 per thousand, respectively. This rate was approximately twice the overall annual rate of 1.42 per 1000. The seasonal distribution (Table III) revealed a higher rate in autumn and a lower rate in spring (southern hemisphere). These differences were not statistically significant (chi2 = 7.37; df = 3; p = 0.08).

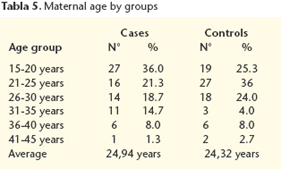

The distribution by ABO and Rh blood groups of the case infants, control infants, and their mothers is shown in Table IV. The O allele was prevalent for the ABO system (55.0%) and the D allele (Rh+) was prevalent for the Rh system (99%) in all groups. The presence or absence of the d allele of the Rhesus system showed that the study population had 52.9% indigenous admixture. The age range of the mothers of case infants was 15 to 42 years, with 36% in the 15 to 20-year age group and a progressively smaller percentage in other age ranges until the 41 to 45-year group. The age range of the control mothers was 17 to 44 years. The largest group of control mothers was 21 to 25 years, with 36%. The group of mothers age 15 to 20 years of case infants was larger than the respective group of control mothers. This difference was statistically nonsignificant (chi2 = 9.61; df = 5; p = 0.09) (Table V).

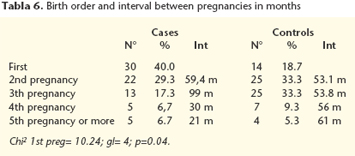

The birth order of the case and control mothers and intervals between pregnancies are shown in Table VI. Primiparity was found in 30 (40%) case mothers as opposed to 14 (18.7%) control mothers (chi2 = 10.24; df = 4). The index pregnancy was the second or third for many control mothers, and less frequently, the fourth pregnancy or more. This was also true among case mothers.

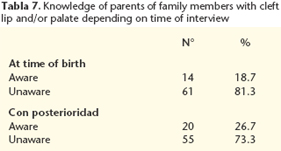

The number and percentage of parents who reported a familial incidence of cleft lip and/or palate when questioned at birth versus the number who gave this information in later months is summarized in Table VII. The percentage of parents aware of a familial case of cleft lip and/or palate increased in interviews held months or years after the index birth. The survey disclosed 26.7% of families with at least one other family member affected.

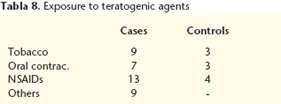

Cases of parents exposed to teratogens before and during pregnancy are analyzed in Table VIII. Nine case mothers versus 3 control mothers reported smoking during pregnancy. The difference was not statistically significant due to sample size. Only one case mother reported alcohol intake during pregnancy. Seven case mothers versus 3 control mothers took oral contraceptives in the first weeks after fertilization. A total of 17 mothers took nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs during pregnancy for common colds and/or headache. This group contained 13 case mothers versus 4 control mothers. Finally, 2 case mothers reported being radiated during pregnancy and 6 were exposed to harmful agents during work. In the latter group, 5 worked with agricultural products and in one instance both case parents had contact with industrial cleaning products.

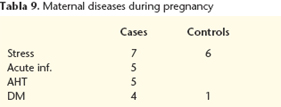

The pathologies that affected mothers during pregnancy included 13 mothers who reported stress due to an unwanted pregnancy or chronic depression. The distribution was similar in both groups with 7 case mothers and 6 control mothers. Five case mothers had serious infections that required antibiotic therapy. Five case mothers had arterial hypertension and 4 had diabetes mellitus or gestational diabetes. These results are summarized in table IX.

Discussion

Cleft lip and/or palate are the most frequent craniofacial malformations in the world. In Chile this malformation is an important problem because of its prevalence and the consequences for the patient and the patients circle.19

Many studies have been made to clarify the etiology of this conditions, but no cause has been identified, only a series of predisposing genetic and environmental factors.

The prevalence of cleft lip and/or palate in our study was 1.42 per 1000 live births, or approximately 1 out of 704 births, a rate similar to the national average.1,20 The distribution by diagnosis and sex coincides with the expected patterns, with an approximate ratio of 1:2:1 for CL, CLMP, and CP. CL and CLMP affected males and the left side more often. CP was more frequent among females. In primary cleft lip and/or palate, the side most often affected is the left side, although the difference between sides is greater than expected in the CLMP group.

We observed a seasonal variation in the occurrence of this malformation, with a higher rate in autumn, corresponding to children conceived in winter. In winter, there is a predisposition to respiratory tract infections associated with the use of anti-inflammatory agents and antibiotics. This difference is not statistically significant, probably due to the sample size. Similar studies in other areas of Santiago21 confirm this finding.

The reference population of the study hospital is of low to medium socioeconomic level, strata that are related with a greater degree of Amerindian extraction and probably with higher rates of cleft lip and/or palate.7,22

The study of Amerindian ethnicity by the frequency of the O allele and the ABO and Rh systems confirmed a high percentage of Amerindian ethnicity among the study subjects. There was an almost complete correlation between degree of Amerindian admixture and prevalence rates. We obtained the highest percentage of Amerindian ethnicity among published studies,23,24 which correlated with the high frequency of cleft lip and/or palate. However, in high altitude locations like Chuquicamata and Calama, higher rates of cleft lip and/or palate are observed, although the percentage indigenous extraction is lower.23 This finding confirms the importance of environmental factors in the appearance of cleft lip and/or palate, thus supporting the hypothesis of a multifactorial origin.

As in other studies, we found that cleft lip was more frequent in males and cleft palate was more frequent in females. In males and females, unilateral cleft lip affects mainly the left side, which remains unexplained.

Of the case mothers, 40% were primigravid and 36% belonged to the youngest age group.

Another important factor in susceptibility to cleft lip and/or palate is maternal age. Some studies indicate that the mothers at greatest risk are older than 35 years.14,25 However, our study found more mothers under the age of 20 years. This is directly related with the number of primigravid mothers, which in our study were more numerous in the case group than in the control group. In Chile, there has been a progressive increase in the number of pregnancies in women under 19 years in the last two decades (INE). Multiple risk factors converge in the adolescent pregnancies of the study population, e.g., poverty, low educational level, unemployment, and alcohol and drug use, among others. From this perspective, it is likely that any intervention targeting this segment will benefit the group as a whole, perhaps reducing the incidence of oral clefts.

There is a high familial incidence of cleft lip and/or palate in Chile.6 In our study 26.7% of the families surveyed knew of a case among their relatives. It is important to emphasize the importance of the time when the survey is made because the mother often lacked information about her own family or that of the father in the first days of her childs life. When the survey was made a few months after birth, the mother usually had made inquiries and knew her family history. In our study, 6 women found previously affected relatives that they had been unaware of.

Different environmental factors have been identified as possible causes of the malformation. Tobacco smoke, generally associated with ingestion of alcohol and other toxins, are noteworthy. We found that part of the population smoked during pregnancy in our study. More case mothers than control mothers were smokers.11

Oral contraceptives were another agent used during pregnancy. In these cases the mother failed to realize that she was pregnant and continued taking contraceptives for an average of two months of pregnancy. It is important to note that Peterson27 and Bracken28 have associated the use of oral contraceptives with congenital malformations.

Another risk factor was occupational exposure of the parents to chemical agents. The fact that 5 out of 6 cases of chemical exposure involved parents who worked on farms before and after conception merits mention. This coincides with the findings of Gordon and Shy29 and Croen et al30 and is related to the intensive industrialization of farming in central Chile.

Pathological conditions of the pregnant mother or their treatment usually affect the intrauterine development of the infant. The stress of pregnant women, generally related with an unwanted pregnancy, is a common condition among adolescent mothers. As Palomino et al24 suggest, some mental disorders may play an important role in the appearance of cleft lip and/or palate. For instance, it is often associated with tranquilizer use, which is a confirmed teratogen.31

It also is known that chronic pathologies like diabetes mellitus (DM) and arterial hypertension (AHT) are risk factors for malformations in offspring. Among the case mothers, 5 women had AHT during pregnancy and 4 had DM. It is postulated that there would be an early reduction of uteroplacental blood flow in hypertension and that the hyperglycemic medium would be teratogenic in diabetes.16

Conclusions

Risk factors for malformations of the lip and/or palate among the reference population of the Felix Bulnes University Hospital were:

• First pregnancy in women younger than 20 years old.

• Large proportion of Amerindian origin and family history of malformations of the lip and/or palate. Risk was greater in:

• Pregnant women who smoked, drank alcohol, or took NSAIDs or oral contraceptives and/or were exposed to radiation.

• Parents who worked with agricultural chemicals, mothers with chronic pathologies like arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus, or mothers who suffered important periods of stress in early pregnancy or a serious infection.

Our study supports the multifactorial heredity hypothesis of susceptibility to cleft lip and/or palate.

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Juan Cortés Araya

Facultad de Odontología, Universidad de Chile

Av. Santa María 571, Santiago, Chile

Email:

jcortes@uchile.cl

Recibido: 09.10.06

Aceptado: 11.01.08

References

1. Protocolo AUGE, fisura labiopalatina para niños. Disponible en: www.minsal.cl (Consultado en octubre del 2004). [ Links ]

2. Blanco R, Suazo J, Santos J, Paredes M, Sung H, Carreño H, Jara L. Association between 10 microsatellite markers and nonsyndromic cleft lip palate in the chilean population. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2004;41:163-7. [ Links ]

3. Blanco R, Suazo J, Santos J, Carreño H, Paredes M, Jara L, Eltit G. Evaluación de la asociación entre marcadores de microsatélite en 6p22-25 y fisura labiopalatina no sindrómica utilizando el diseño de tríos caso-progenitores en la población chilena. Rev Med Chile 2003;131:765-72. [ Links ]

4. Blanco R, Suazo J, Santos J, Carreño H, Paredes M, Jara L. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2005;42: 267-71. [ Links ]

5. Palomino H, Cerda-Flores R, Blanco R, Palomino HM, Barton S, De Andrade M, Chakraborty R. Complex segregation analysis of facial clefting in Chile. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol 1997;17:57-64. [ Links ]

6. Palomino H, Guzmán E, Blanco R. Recurrencia familiar de labio leporino con o sin fisura velopalatina de origen no sindrómico en poblaciones de Chile. Rev Med Chile 2000;128:286-93. [ Links ]

7. Vanderas A. Incidence of cleft lip, cleft palate, and cleft lip and palate among races: A review. Cleft Palate J 1987;24:216-25. [ Links ]

8. Palomino HM, Palomino H, Cauvi D, Barton SA, Chakraborty R. Facial clefting and amerindian admixture in populations of Santiago, Chile. Am J Hum Biol 1997; 9:225-32. [ Links ]

9. Rojas A, Ojeda ME, Barraza X. Malformaciones congénitas y exposición a pesticidas. Rev Med Chile 2000;128:399-404. [ Links ]

10. Shaw G, Nelson V, Iovannisci D, Finnell R, Lammer E. Maternal occupational chemical exposures and biotransformation genotypes as risk factors for selected congenital anomalies. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:475-84. [ Links ]

11. Wyszynski D, Duffy D, Beaty T. Maternal cigarrete smoking and oral clefts: a meta-analysis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 1997;34:206-10. [ Links ]

12. Lorente C, Cordier S, Goujard J, Aymé S, Bianchi F, Calzolari E, De Walle H, Knill-jones R. Tobacco and alcohol use during pregnancy and risk of oral clefts.Occupational exposure and congenital malformation working group. Am J Public Health 2000;90:415-9. [ Links ]

13. Källén B. Maternal drug use and infant cleft lip/palate with special reference to corticoids. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2003;40:624-8. [ Links ]

14. Nazer J, Cifuentes L, Ruiz G, Pizarro M. Edad materna como factor de riesgo para malformaciones congénitas. Rev Med Chile 1994;122: 299-303. [ Links ]

15. Pardo R, Nazer J, Cifuentes L. Prevalencia al nacimiento de malformaciones congénitas y de menor peso de nacimiento en hijos de madres adolescentes. Rev Med Chile 2003;131:1165-1172. [ Links ]

16. Ordoñez M, Nazer J, Aguila A, Cifuentes L. Malformaciones congénitas y patología crónica de la madre. Estudio ECLAMC 1971-1999. Rev Med Chile 2003; 131:404-11. [ Links ]

17. Vieira A, Orioli I, Murray J. Maternal age and oral clefts: A reappraisal. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2002;94:530-5. [ Links ]

18. Bernstein F. Die geographische Verteilung der Blutgruppen und ihre anthropologische Bedeutung (pp 227-243) en Comitato Italiano per lo studio del problemi della populazione. Instituto Poligrafico dello stato: Rome 1931.18. [ Links ]

19. Cobourne M. The complex genetics of cleft lip and palate. Eur J Orth 2004;26: 7-16. [ Links ]

20. Nazer H, Hubner G, Catalan M, y cols. Incidencia de labio leporino y paladar hendido en la Maternidad del Hospital Clínico de la Universidad de Chile y en las maternidades chilenas participantes en el Estudio Colaborativo Latino Americano de Malformaciones Congénitas (ECLAMC) período 1991-1999. Rev Med Chile 2001;129:285-93. [ Links ]

21. Blanco R, Cifuentes L, Muñoz MA, Fuchslocher G, Cauvi D, Arancibia X. Fisuras labio-palatinas en Santiago de Chile: Estudio epidemiológico. Rev Med Chile 1988;116:1320-6. [ Links ]

22. Valenzuela C, Acuña M, Harb Z. Gradiente sociogenético en la población chilena. Rev Med Chile 1987;115:295-9. [ Links ]

23. Goycoolea A, Palomino HM, Palomino H, Blanco R. Agentes medioambientales en la susceptibilidad a las fisuras faciales en el Norte de Chile. Odont Chilena 1993;41:113-9. [ Links ]

24. Palomino H, Palomino HM, Goycoolea A. Correlación de la frecuencia de fisuras faciales con atributos socio-genéticos y del medio ambiente en Chile. An Acad A Leng 1991;9:16-24. [ Links ]

25. Vieira A, Orioli I. Birth order and oral clefts: a meta analysis. Teratology 2002; 66:209-16. [ Links ]

26. Smits L, Essen G. Short interpregnancy intervals and unfavourable pregnancy outcome: role of folate depletion. Lancet 2001;358:2074-2077. [ Links ]

27. Peterson W. Pregnancy following oral contraceptive therapy. Obstetric and Gynecology 1969;34:363-7. [ Links ]

28. Bracken M. Oral contraception and congenital malformations in offspring: a review and mata-analysis of the prospective studies. Obstetric and Gynecology 1990;276:552-7. [ Links ]

29. Gordon J, Shy C. Agricultural chemical use and congenital cleft lip and/or cleft palate. Arch Environ Health 1981;36:213-21. [ Links ]

30. Croen L, Shaw G, Sanbonmatsu L, Selvin S, Buffler P. Maternal residential proximity hazardous waste sites and risk for selected congenital malformations. Epidemiology 1997;8:347-54. [ Links ]

31. Dolovich L, Addis A, Vaillancourt J, Barry J, Koren G, Einarson T. Benzodiazepine use in pregnancy and major malformations or oral cleft: meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies. BMJ 1998;317:839-43. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en