Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial

versión On-line ISSN 2173-9161versión impresa ISSN 1130-0558

Rev Esp Cirug Oral y Maxilofac vol.30 no.5 Madrid sep./oct. 2008

Application of botulinum toxin A for the treatment of Freys Syndrome

Aplicación de la toxina botulínica A para el tratamiento del síndrome de Frey

J. Mareque Bueno1, J. González Lagunas2, C. Bassas Costa3, G. Raspall Martín4

1 Médico Residente. Profesor asociado del área de Patología Médico-Quirúrgica.

Universidad Internacional de Cataluña. España

2 Médico Adjunto.

3 Jefe Clínico.

4 Jefe de Servicio.

Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial. Hospital Universitario Vall d´Hebrón. España

ABSTRACT

The auriculotemporal syndrome, also known as gustatory sweating or Freys syndrome, is a condition characterized by sweating and flushing of the cutaneous territory innervated by the auriculotemporal nerve while eating.

Freys syndrome is probably an inevitable sequela of parotid gland surgery. Once it appears, it persists for the rest of the patients life if not treated. It has been reported that performance on the Minor test after parotid gland surgery is 100% positive and 50% of patients are symptomatic, experiencing sweating during meals. About 15% consider their symptoms serious.

In this article we present the results of our study of the treatment of Freys syndrome by intradermal injection of botulinum toxin A and the follow-up of the patients.

The patients symptoms disappeared during a mean period of 16 months with some individual variability. These results suggest that injection of botulinum toxin A could be a technique of choice for established Freys syndrome.

Key words: Parotidectomy; Freys syndrome; Botulinum toxin A.

RESUMEN

El síndrome Aurículo-temporal también conocido como sudoración gustativa o síndrome de Frey, es una entidad caracterizada por sudoración y enrojecimiento de la piel del territorio inervado por el nervio aurículo-temporal durante las comidas.

El síndrome de Frey es probablemente una secuela inevitable en la cirugía de la glándula parótida. Una vez que se presenta se perpetua durante toda la vida si no se realiza tratamiento. Realizando el test de Minor tras cirugía sobre la glándula parótida ha sido publicado que el 100% son positivos, y que el 50% son sintomáticos percibiendo la sudoración durante las comidas, y alrededor de un 15% consideran sus síntomas graves.

En el siguiente articulo presentamos los resultados de nuestro estudio que consistió en la inyección intradérmica de toxina botulínica A a nuestros pacientes con síndrome de Frey y el seguimiento.

Los resultados han sido desaparición de los síntomas durante un periodo medio de 16 meses con cierta variabilidad individual. Con estos resultados podría considerarse la inyección de toxina botulínica A como ténica de elección para el síndrome de Frey ya establecido.

Palabras clave: Parotidectomía; Sindrome de Frey; Toxina botulínica A.

Introduction

The auriculotemporal syndrome, also known as gustatory sweating or Freys syndrome, is a condition characterized by sweating and flushing of the skin territory innervated by the auriculotemporal nerve while eating.

This name is due to Lucie Frey, although she was not the first to describe the condition. Baillanger had already described the condition in 1853 and the first description also is attributed to M. Duphenix, in 1757. However, authors like Dulguerov argue that the case reported by Duphenix was a salivary fistula and not auriculotemporal syndrome.

The pathophysiology of the condition was attributed shortly after by Andre Thomas to aberrant reinnervation by the cholinergic parasympathetic fibers that normally innervate the parotid gland. Once surgery or trauma to the parotid gland has occurred, the postganglionar fibers that innervated the gland are sectioned. They come into contact with the vessels and sweat glands of the skin during their regeneration. It is believed that an aggression against the sympathetic fibers is necessary. The neurotransmitter of these fibers, paradoxically, is also acetylcholine (ACh). Under normal circumstances, the sympathetic fibers innervate the cutaneous vessels and sweat glands, which facilitates aberrant reinnervation.

As a consequence of the activation of these aberrant fibers, which synapse with the glandular parenchyma under normal conditions, the neurotransmitter (ACh) is released into the dermis, producing localized cutaneous vasodilatation and hyperhydrosis, which is the main symptom of the auriculotemporal syndrome (Laskawi et al., 1999). This theory, although never demonstrated objectively, is commonly accepted as the pathophysiologic explanation of the condition as acetylcholine (ACh) acts as a neurotransmitter in both postganglionar receptors.

Freys syndrome is probably an inevitable sequela of parotid gland surgery. Once it appears, it persists for the rest of the patients life if not treated. It has been reported that performance on the Minor test after parotid gland surgery is 100% positive and 50% of patients are symptomatic, experiencing sweating during meals. About 15% consider their symptoms serious.

The symptoms described are variable, ranging from conditions of isolated local pain or isolated erythema, accompanied or not by local hyperthermia, to conditions of sweating of variable intensity that, in the most serious cases, cause sweat to drip from the patients cheek.

Working hypothesis

Botulinum toxin has acquired a prominent role in the treatment of diverse pathologies (Rossetto et al., 2001), ranging from cosmetic procedures to conditions with functional disorders. In order to understand the basis of its clinical use, certain fundamental aspects of the molecule must be known.

Botulinum toxin is the most toxic substance known (Niamtu, 2003). It is four times more lethal than an equivalent dose, 1 x 1010, of tetanus toxin, more lethal than curare, and 100 x 1010 more lethal than cyanide (Arnon et al., 2001).

Botulinum toxin exercises its effect on the presynaptic part of the neuromuscular junction, impeding the release of acetylcholine (Brin, 2000). Acetylcholine-releasing nerve terminals are found in the motor plates and synapses of the autonomic nervous system (ANS). Once botulinum toxin A adheres to the terminal, the amount of ACh released after depolarization diminishes.

The mechanism of action is divided into three main stages: adherence, internalization, and inhibition of neurotransmitter release.

A number of studies have demonstrated the safety of local applications of botulinum toxin. The risk of the use of this molecule for curative purposes is not considered, because it is already being used at even higher doses for cosmetic purposes (approved by the FDA) for the elimination of expression wrinkles of the face.

The first citation in the literature referring to the use of botulinum toxin to produce anhydrosis in humans is in 1994 (Bushara 1994). Bushara described this effect of the toxin in treating patients with hemifacial spasm; the same group reported the results of the specific use of botulinum toxin in focal hyperhydrosis, in this case axillary hyperhydrosis, two years later (Bushara et al., 1996).

Since these studies, various reports of the intradermal application of the toxin to prevent hyperhydrosis have shown clearly that it is a safe, effective, and well tolerated treatment. It has been shown to be a valid alternative to classic treatments, whether topical, systemic, or surgical (Heckmann et al., 2001; Naumann et al., 1998).

The preparations of botulinum toxin A available are: Botox® (Allergan, Irving, CA) or Dysport® (Ipsen, Paris). The dosage used ranged from 50 to 100 units and the dilution was 2.5 to 5 ml per 100 units of toxin.

Since the auriculotemporal syndrome, or Freys syndrome, is a case of focal hyperhydrosis, as confirmed by the hypotheses formulated in the literature, it would seem logical to think that the intradermal application of an anticholinergic agent like botulinum toxin A (Botox®), might irreversibly block the postsynaptic receptors in the membrane of the eccrine sweat gland responsible for hyperhydrosis in the days after injection.

Sweating occurs in the preauricular area while eating due to the aberrant reinnervation of Ach-releasing fibers in the dermis of the preauricular region that synapses with eccrine sweat glands. Previously, these fibers controlled saliva secretion by the parotid gland.

Applications of botulinum toxin allow the patient to remain free of the clinical manifestations of the condition for a certain period, thus avoiding the deterioration in the quality of life associated with Freys syndrome.

The ethics committee of our center authorized the study of this indication of botulinum toxin A.

The primary objective of this study was to demonstrate that the use of intradermal botulinum toxin A is an effective method for controlling sweating and flushing symptoms in the auriculotemporal syndrome.

Study the appearance of side effects to the injection of high doses of botulinum toxin A in the target region at either the local or systemic level.

Determine whether the technique has low morbidity.

Analyze whether the technique is reproducible and whether a protocol for use can be developed.

Determine the duration of the sweat-free effect after the application of a specific dose of toxin.

Provide patients with auriculotemporal syndrome a safe, lasting, and easily applicable solution for their localized preauricular hyperhydrosis.

Material and method

A retrospective review was made of 411 patients with salivary gland pathology who had undergone a total of 429 surgical interventions on the parotid or submaxillary gland. Benign and malignant pathologies were included.

The patients were 208 men and 203 women with ages ranging from 13 to 92 years (mean age: men, 52 years, and women, 49 years). The total number of operations (including recurrences and bilateral cases) was 429.

A total of 289 interventions were performed on the parotid gland (148 men and 141 women). Of all the patients treated for parotid pathology, 68 had malignant neoplasms, 205 benign tumor pathology, and 15 benign salivary pathology (parotitis, salivary cysts, etc).

The occurrence of complications associated with the procedure was registered in this review, finding the following complications:

Transitory facial paralysis 52 (13.3%)

Freys syndrome 31 (7.2%)

Permanent facial paralysis 14 (3.6%)

Severe local infections 14 (3.2%)

Severe esthetic defect 7 (1.6%)

Severe bleeding/bruising 6 (1.4%)

Salivary fistula 5 (1.1%)

Other 3 (0.7%)

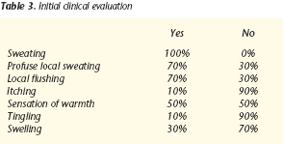

Freys syndrome was the second most frequent complication after transitory facial paralysis and before permanent facial paralysis. It manifested clinically as auriculotemporal syndrome in 31 cases and occurred in 11.52% cases of parotid gland surgery.

It must be emphasized that this percentage represents patients with clear clinical manifestations who went to outpatient clinics months after the intervention for preauricular sweating that coincided with eating, which we classified as symptomatic Freys syndrome. The incidence of subclinical Freys syndrome is higher, as reflected in studies of the condition (Guntinas-Lichinus et al., 2003), and may even reach 100% of cases. If we analyze the appearance of the syndrome in relation to the cumulative frequency of each specific surgical technique, as shown in the table, the surgical technique that was accompanied most often by Freys syndrome was total parotidectomy. From this sample of 31 patients affected, we selected the patients who met the following inclusion criteria:

Age over 18 years

Presence of symptomatic Freys syndrome

Presence of benign pathology (patients with malignant parotid gland neoplasms were excluded)

Absence of allergy or intolerance to either botulinum toxin or any of the excipients of the preparation

Not pregnant or breastfeeding

Absence of skin infection in the area of hyperhydrosis

Absence of neuromuscular disease: myasthenia gravis, Eaton-Lambert syndrome, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)

Absence of uncontrolled systemic disease (diabetes, nephropathy, cardiopathy, vasculopathy)

The patients selected were contacted by telephone and invited to enter the study. They were informed about the possible side effects of the use of botulinum toxin type A (Botox®).

Out of a total of 31 patients found in the review of clinical histories from the period mentioned, 7 were excluded for malignant pathology, 20 were contacted successfully and only 10 patients decided to enter the initial study.

The patients who agreed to enter the study were required to complete a form detailing their age, date of intervention, date of appearance of symptoms, and clinical manifestations of the syndrome.

Sweating.

Profuse local sweating.

Local flushing.

Itching.

Sensation of warmth.

Tingling.

Swelling.

Influence on quality of life: not a lot (1) / some (2) / a lot (3).

At the second visit, scheduled in the morning and with the patient instructed to fast overnight, the Minor test (Minor, 1927) was performed to quantify the skin surface affected in square centimeters. The test was conducted in a standardized way.

The patients included in the study who reached the end of the observation period are listed in the following table 2.

Once the area affected by local hyperhydrosis was delimited, botulinum toxin A (Botox®) was injected intradermally. Starting at the most distal part of the area affected and continuing upwards, 0.1 ml of the preparation, which contained 10 units of botulinum toxin, was injected in the center of each square centimeter of the area delimited.

The injection technique consisted of angling the needle as tangentially as possible to the skin surface and introducing the tip of a BD Plastipack® needle. Once the tip of the needle was positioned in the dermis, 0.1 ml was infiltrated into the center of each square centimeter.

In no case were the areas of risk for altering facial expression encroached on; injections never passed the anterior limit constituted by the anterior edge of the masseter muscle (to avoid altering the mouth expression dependent on the orbicularis oris) or the superior limit constituted by the lower margin of the orbicularis oculi muscle (to avoid altering eye expression).

Intradermal injections were made without infiltrative or topical anesthesia; local cold was applied percutaneously as required by a patient.

Follow-up

Each patient was followed up regularly by performing the Minor test at each visit to quantify the effect. Visits were scheduled at the following intervals: 15 days, one month, three months, six months, nine months, twelve months, fifteen months, and eighteen months after the injection. The patient was instructed to return to the clinic immediately if sweating reappeared in the area during the follow-up period.

During each visit, a questionnaire was completed systematically to detect undesirable effects:

Local undesirable effects

1. Pain

2. Edema

3. Ecchymoses

4. Headache

5. Dry mouth

6. Alteration of mouth expression

7. Alteration of eye expression

Systemic undesirable effects

1. Nausea

2. Vomiting

3. Faintness

Results

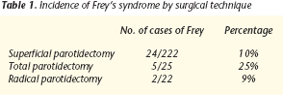

In the initial evaluation, patients gave the following questionnaire responses, shown in table 3.

The influence on the quality of life was described as:

Not a lot 30%

Some 60%

A lot 10%

During follow-up, it was observed that the effect began 48 hours after injection of the toxin and reached its maximum effect beginning 10-14 days after injection; clinical manifestations disappeared completely. The patients did not present any sweating when tested during follow- up.

None of the patients referred any local side effects (pain, edema, ecchymoses, headache, dry mouth, alteration of mouth expression, alteration of eye expression) or systemic side effects (nausea, vomiting, faintness).

These results were accompanied by a subjective improvement in the quality of the life of patients as the evaluation questionnaire to which the patients responded showed. Patients indicated that quality of life was greatly improved in every case.

Duration of effect

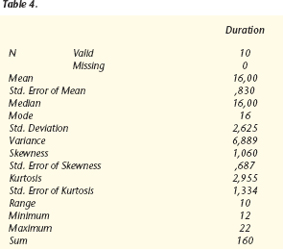

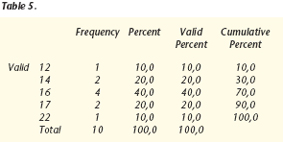

The results were analyzed with WIN QSB 14.0 Microsoft©, obtaining the following data:

The effect had a duration of about 16 months, with a mean and mode of 16 months. Interindividual variability was observed, the standard deviation being 2.6 months and the variance, 6.8 months.

Values were within a range of 10 months, with a minimum of 12 months and a maximum of 22 months.

The total sum of sweat-free months in the 10 patients was 160 months.

The most frequent value was 16 months, which had 4 observations.

Discussion

In recent years, a variety of surgical and nonsurgical treatments to manage the clinical manifestations of these patients have been proposed in many articles. Our results and the results reported in the literature do not seem to indicate any differences in the incidence of auriculotemporal syndrome in relation to benign or malignant pathology, sex, or age. There may be a relation with the aggressiveness of the surgical technique because the syndrome occurred in a higher percentage of the patients who underwent total parotidectomy than in those who underwent superficial parotidectomy.

On the basis of the literature, it also seems that the duration of the effect is dose-dependent. This dose dependence is the object of the second phase of this study, which currently is under way in our unit. In this second phase, a second group of 10 patients is receiving botulinum toxin A at a dose twice as high as the dose used in the present study. The aim is to evaluate the duration of the symptom-free interval.

The clinical relevance of patient number 10 is underlined because different doses were injected on each side of the face. We expect to collect useful data during the follow-up of this patient that may give us useful guidance with regard to the dose-dependent duration. Diverse therapies have been tried in attempt to palliate the symptoms originated by aberrant auriculotemporal reinnervation, such as: sympathectomy, radiotherapy, topical anticholinergics, interposition of muscular flaps, alloplastic materials, acellular dermis, and other materials, with widely varying results.

The therapeutic and preventive modalities for Freys syndrome can be divided into surgical and nonsurgical.

Nonsurgical techniques

Topical treatments

Glycopyrrolate or scopolamine (substances with anticholinergic properties): these compounds have long been used empirically as the treatment of choice for focal hyperhydrosis because the eccrine glands are stimulated by acetylcholine. Anticholinergics have two main problems. Firstly, their cutaneous absorption is generally insufficient, and secondly, increasing topical doses to resolve this absorption problem can cause systemic side effects of cholinergic blockade to appear. Cases of sensitization to these agents have been reported (Kim Won-Oak et al., 2003).

Aldehydes: formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde have been used to treat hyperhydrosis. Their mechanism of action seems to be blockade of the duct of the sweat gland as a result of denaturing the keratin of the proximal pore of the eccrine gland (Sato, 1999). The obstruction seems to be limited to the superficial part of the stratum corneum and epidermal regeneration reopens the lumen of the duct in a few days, which means that applications must be almost daily. Topical use is associated with important side effects of irritation and sensitization to the agent in up to 20% of cases.

Anesthetics: Local anesthetics have been used to relieve symptoms in cases of focal hyperhydrosis; they exercise their effect by blocking the nerve branches responsible for the territory involved (Guntinas-Lichinus, 2003). Given the lack of a clear pattern of innervation in the case of auriculotemporal syndrome, the use of anesthetics has not produced good results.

Aluminum chloride: an active ingredient in most topical antiperspirant agents, in addition to other metal salts. Aluminum chloride has an anhydrotic effect, obstructing the distal part of the ducts of the eccrine sweat gland and facilitating the formation of a precipitate. Clinical improvement is noticeable within 3 weeks of beginning treatment (Huttenbrink et al., 1986). Side effects including a burning sensation and irritation.

Iontophoresis: consists of the direct introduction of ionized particles in the skin by the applying a direct electrical current. The exact mechanism of action is not clear, but it has been postulated that it involves the action of a charged particle that obstructs the duct or an alteration produced by the electrical charge that alters the excretory function of the eccrine gland. It was popular in 1968 (Levit). As a drawback of the technique, iontophoresis produces important irritation, dryness, hair loss, and fragile skin in the treated area. The procedure also is very time-consuming, requiring about thirty minutes a day per treatment zone, for at least four days a week.

Systemic agents: oral anticholinergic agents (Guntinas- Lichius, 2003) have been used for diverse hyperhydrosis conditions in a variety of sites. They function as acetylcholineinhibiting competitors at the level of the synapse. The problem with anticholinergics is the absence of specificity for eccrine sweat glands. They produce generalized cholinergic blockade, resulting in: blurred vision, dry mouth, tachycardia, and urine retention.

Isolated cases treated with other drugs having a systemic effect have been reported in the literature (Clayman et al., 2006), such as: sedatives (diazepam), beta blockers (propranolol), spasmolytics (belladona), nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs (indomethacin), and calcium channel blockers (diltiazem).

Radiotherapy: this therapy has not been very successful and it has severe side effects (Dulguerov et al., 2000).

Surgical techniques

Surgical treatment is based on the presumptive mechanism of aberrant reinnervation of the parasympathetic fibers that synapse with skin vessels and the overlying sweat glands, causing flushing and sweating during meals. The surgical techniques described in the literature prevent the stimulation of sweat glands by either neurectomy of the chorda tympani (Golding-Wood, 1962) or section of these reinnervated fibers with interposition of materials between the skin and parotid gland. Interposition materials include: temporal fascia or fascia lata flaps (Wallis et al., 1978), platysmal flaps (Kim et al., 1999), temporal fascia flaps (Cesteleyn et al., 2002), sternocleidomastoid muscle flaps (Gooden et al., 2001; Kerawala et al., 2002), superficial musulo-aponeurotic system flaps (SMAS) (Hönig, 2004; Allison and Rappaport, 1993; Angspatt et al., 2004; Bonanno et al., 2000), dermal grafts (Harada et al., 1993), fat grafts (Hönig et al., 2004), alloplastic materials like expanded Polytef® (Dulguerov et al., 1991; Shemen et al., 2003), and other techniques (Prokopakis et al., 2005).

Since Gutiérrez proposed in 1903 an incision for the resection of parotid tumors, several proposals have been made to modify the incision to avoid disfiguring scars. The advantage of the incision proposed by the author is that it does not leave visible scars, but it offers good access to the parotid gland for resection, similar to that obtained with the procedure described by Ferreria et al. (1990), which produced good exposure of the five branches. The differences in color and texture achieved are less obvious. This approach was first proposed by Appiani et al. (1967) and has been defended in the literature by other authors, including plastic surgeons, maxillofacial surgeons, and ear, nose and throat surgeons. However, without added maneuvers, this incision alone does not prevent the appearance of a postoperative depression in the area. For decades, auriculotemporal syndrome has been described as a common and inevitable complication of parotidectomy. Despite the fact that it seems that it can be prevented by raising a flap superficial to the SMAS, the occurrence of auriculotemporal syndrome is generally unforeseeable.

Hönig (2004) proposes parotidectomy with a face-lift approach, using a rotation and advance flap of musculature of the superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS) as a way of improving the esthetic appearance of the scar, reducing skin tissue depression over the surgical bed in the postoperative period, and lowering the frequency of auriculotemporal syndrome.

Using the technique described, Freys syndrome is less frequent as the result of interposition of a hybrid layer of biocompatible Vicryl mesh and SMAS. The author proposes that aberrant reinnervation can be avoided and, consequently, the occurrence of the condition. This makes it possible to prevent the appearance of the syndrome while correcting the esthetic problem of the depression in the area of the mandibular angle.

Prokopakis (2005) proposes the use of the LigaSure Vessel Sealing System (LVSS®, Valleylab, Boulder, CO). This device is similar to a bipolar electrocautery and is used to control bleeding. It has been approved by the FDA for vessels of up to 7 mm. It produces hemostasis by denaturing the collagen and elastin of the vessel walls and surrounding connective tissue. LVSS showed effectiveness in preventing Freys syndrome in the series presented by Prokopakis; out of a total of twelve cases, none developed the condition. The sample size does not allow statistically valid conclusions to be drawn, but it suggests a new alternative for preventing auriculotemporal syndrome.

Other authors (Cesteleyn et al., 2002) propose the use of musculo-aponeurotic flaps of temporoparietal fascia (TPF) as an effective method for preventing Freys syndrome. Results are conclusive; compared to the classic technique, the occurrence of gustatory sweating decreased from 33% to 4% in the patients operated on with this technical modification of muscular flap interposition between the facial nerve and skin, whether TPF, sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM), or SMAS-platysma. Likewise, authors like Casler (1991), Bonanno et al. (2000), and Alisson (1993) have obtained similar results of 0 to 1% with this technique.

Meningaud et al. (2006) obtained very good results with SMAS flaps and the face-lift approach, not only with regard to filling the depression in the submandibular area but also in preventing sweating, which coincides with the results of Cesteleyn et al. (2002), which showed a fall in the appearance of Freys syndrome from 33% to 4%. Allison and Rappaport (1993) found only two cases of Freys syndrome in 112 patients who underwent surgery with interposition of a SMAS flap.

This SMAS flap could be substituted by a SCM muscle flap, but Gooden et al. (2001) have demonstrated that reconstruction with the SCM flap does not lower the incidence of Freys syndrome and does not significantly modify the esthetic appearance of the depression. A randomized prospective study confirmed these results (Kerawala et al., 2002). Jost et al. (1999) propose a procedure that combines displacement of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. In this flap a superior pedicle is taken from the SCM and a double layer of free graft is obtained from the superficial and deep temporal fascia. This procedure seems complicated and overly prolongs the intervention compared with the SMAS rotation and advance flap technique. The rotational temporoparietal fascia flap is another barrier interposition technique that has been described as preventing Freys syndrome while acting as a soft tissue filler (Zaoli, 1989). Amhed and Kolhe (1999) found a significantly lower incidence of auriculotemporal syndrome and less depression of the mandibular angle. This procedure, however, excessively prolongs the incision in the vertical direction. In order to avoid donor area morbidity, some authors propose using synthetic materials or cadaveric membranes, which may make the procedure even more expensive (Sinha et al., 2003). The SMAS advance flap seems to offer the same advantages without any of the disadvantages.

Other authors, such as Wallis et al. (1978), have used fascia lata flaps, while Harada et al. (1993) propose the use of a dermal fat graft, and Dulguerov et al. and Shemen et al. support the use of expanded Polytef®. These techniques have a disadvantage with respect to the others proposed because they are avascular nature and do not provide the necessary volume to conceal the esthetic defect. These techniques show promising results.

Lately, the intradermal injection of botulinum toxin has been shown to be a safe and useful method for controlling the symptoms of focal hyperhydrosis of established auriculotemporal syndrome.

In November 1995, Drobik published a series of 14 patients treated with botulinum toxin A. Intradermal injections of a dose of 0.5 U/cm2 on the area positivized the Minor test. The effects disappeared in 2 days without showing side effects.

Schulze-Bonhage in 1996 treated with botulinum toxin A three patients with Freys syndrome in the preauricular region as a result of gunshot wounds or parotid surgery. The effect was established in 2 weeks and produced disappearance of the clinical manifestations for a duration of 8 months, without reporting any side effects.

The following year, Bjerkhoel made a study of 102 patients, 31 of which had reported sweating in the preauricular region in the months after surgery. In 15 of these patients, the Minor test was performed and botulinum toxin A (Botox®) was injected; clinical symptoms disappeared fully in 12 of the 15 patients and partly in the remaining 3, for a duration of 13 months. A local complication involving transitory affectation of the orbicularis oris muscle was described.

In view of the results obtained in our study and reported in the literature, intradermal botulinum toxin A injection seems to be the treatment of choice in patients with established auriculotemporal syndrome.

Although surgical interposition techniques using flaps or a variety of materials also could resolve some cases, the increased morbidity and cost and diminished effectiveness compared with botulinum toxin A treatment seem to rule out these techniques for preventing Freys syndrome at the time of the initial intervention. Botulinum toxin A, aside from preventing some cases, has the effect of improving the esthetic result.

In recent years, the use of botulinum toxin A has extended to palliating the symptoms of auriculotemporal syndrome, but we still do not know the optimal dosage. We used a larger dose in our study than in earlier studies without observing any side effects and still remaining well distanced from the threshold of systemic toxicity.

In view of the recent results reported (Guntinas-Lichius 2002), it seems obvious to think that the higher the dose is, the longer the symptom-free interval will be. The next step is to contemplate increasing the dose, as long as we do not approach the threshold at which side effects could appear. Some of the therapeutic regimens discussed above have resulted in symptom-free periods of up to 2 years. Blitzer (2000) suggests that the use of botulinum toxin could even be curative in the case of Freys syndrome, by producing atrophy of sweat glands and permanent denervation. The reason why this occurs only in certain patients is not known.

Conclusions

1. Intradermal injection of botulinum toxin A is an effective method for controlling the symptoms of sweating and flushing present in established auriculotemporal syndrome.

2. The injection of high doses of botulinum toxin A in the affected region did not trigger local or systemic side effects.

3. The procedure is clearly an ambulatory procedure that is easily administered in outpatient clinics, thus dispensing with the need for hospital admission or the use of surgical facilities.

4. The technique was accompanied by low morbidity because no adverse effects occurred during or as a result of the injection.

5. It is a reproducible technique for which a protocol can be developed. The injection can be repeated when the effect wears off.

6. The duration of the sweat-free effect with a dose of 10 U/cm2 was a mean 16 months.

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Javier Mareque Bueno

Hospital Universitario Vall dHebron. España

E-mail: javier.mareque@gmail.com

Recibido: 08.10.2007

Aceptado: 21.07.2008

References

1. Duphenix M. Observations sur les Fistules du Canal Salivaire de Stenon. Sur une plague complique´e a la ione ou le canal fut de´chine´. Mem Acad R Chir 1757;3:431-9. [ Links ]

2. Dulguerov P, Marchal F, Gysin C. Frey syndrome before Frey: the correct history. Laringoscope 1999;109:1471-3. [ Links ]

3. Laskawi R, Ellies M, Rodel R, Schoenebeck C: Gustatory sweating: clinical implications and etiologic aspects. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1999 ;57:642-8, discussion 648-649. [ Links ]

4. Minor V. Ein neues verfahren zu der klinischen untersuchung der schweissabsonderung. Dtsch Z Nervenheilkd. 1927;101:302. [ Links ]

5. Rossetto O, Seveso M, Caccin P, Schiavo G, Montecucco C. Tetanus and botulinum neurotoxins: turning bad guys into good by research. Toxicon. 2001;39:27-41. [ Links ]

6. Niamtu Jr 3rd. More on Botox treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;127:645-6. [ Links ]

7. Arnon SS, Schechter R, Inglesby TV, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, Fine AD, Hauer J, Layton M, Lillibridge S, Osterholm MT, OToole T, Parker G, Perl TM, Russell PK, Swerdlow DL, Tonat K; Working Group on Civilian Biodefense. Botulinum toxin as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA. 2001 28;285:1059-70. [ Links ]

8. Brin MF. Botulinum toxin therapy: basic science and overview of other therapeutic applications. In: Blitzer A,Binder WJ, Boyd JB, Carruthers A, eds. Management of Facial Lines and Wrinkles. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000:279-302. [ Links ]

9. Bushara. Botulinum toxin and sweating. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:1437-8. [ Links ]

10. Bushara KO, Park DM, Jones JC, Schutta HS. Botulinum toxin—a possible new treatment for axillary hyperhidrosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:276-8. [ Links ]

11. Guntinas-Lichius O. Facial Plastic clinics of North America 11 (2003) 503-513. [ Links ]

12. Kim WO, Kil HK, Yoon DM, Cho MJ. Treatment of compensatory gustatory hyperhidrosis with topical glycopyrrolate. Yonsei Med J. 2003;44: 579-82. [ Links ]

13. Sato K, Kang WH, Saga K, Sato KT. Biology of sweat glands and their disorders. II. Disorders of sweat gland function. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:713-26. [ Links ]

14. Huttenbrink KB. Therapy of gustatory sweating following parotidectomy. Freys syndrome. Laryngol Rhinol Otol. 1986;65:135-7. [ Links ]

15. Clayman MA, Clayman SM, Seagle MB. A Review of the Surgical and Medical Treatment of Frey Syndrome. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;57:581- 4. [ Links ]

16. Dulguerov P, Marchal F, Cosendai C, Piletta P, Lehmann W. Frey syndrome treatment with botulinum toxin. OHNS 2000;122:821-7. [ Links ]

17. Golding-Wood PH. Tympanic neurectomy. J Laryngol Otol 1962;76: 683-93. [ Links ]

18. Wallis KA, Gibson T: Gustatory sweating following parotidectomy: Correction by a fascia lata graft. Br J Plast Surg 31:68, 1978. [ Links ]

19. Kim SY, Mathog RH. Platysma muscle-cervical fascialsternocleidomastoid muscle (PCS) flap for parotidectomy. Head Neck 1999;21:428- 33. [ Links ]

20. Cesteleyn L, Helman J, King S, Van de Vyvere G: Temporoparietal fascia flaps and superficial musculoaponeurotic system plication in parotid surgery reduces Freys syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 2002;60: 1284-97 discussion 1297-8. [ Links ]

21. Gooden EA, Gullane PJ, Irish J, Katz M, Carroll C: Role of the sternocleidomastoid muscle flap preventing Freys syndrome and maintaining facial contour following superficial parotidectomy. J Otolaryngol 30: 98-101, 2001. [ Links ]

22. Kerawala CJ, McAloney N, Stassen LF: Prospective randomised trial of the benefits of a sternocleidomastoid flap after superficial parotidectomy. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 40: 468-72, 2002. [ Links ]

23. Hönig JF. Facelift approach with a Hibrid SMAS rotation advancement flan in parotidectomy for prevention of scars and contou deficiency affecting the neck and sweat secretion of the cheek. J Craniofac Surg 2004;15:797-803. [ Links ]

24. Moreno Garcia C et al. Colgajo de SMAS en la prevención del síndrome de Frey. RECOM 2006;28,3:182-7. [ Links ]

25. Allisson GR, Rappaport I: Prevention of Freys syndrome with superficial musculoaponeurotic system interposition. Am J Surg 1993; 166:407. [ Links ]

26. Angspatt A, Yangyuen T, Jindarak S. The role of SMAS flap in preventing Freys syndrome following standard superficial parotidectomy. J Med Assoc Thai 2004;87:524-7. [ Links ]

27. Harada T, Inoue T, Harashina T, et al: Dermis-fat graft after parotidectomy to prevent Freys syndrome and the concave deformity (see comments). Ann Plast Surg 31:450, 1993. [ Links ]

28. Dulguerov P, Quinodoz D, Cosendai G, et al: Prevention of Freys syndrome during parotidectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 125:833, 1991. [ Links ]

29. Shemen LJ: Expanded polytef for reconstructing postparotidectomy defects and preventing Freys syndrome. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;121: 1297-307. [ Links ]

30. Sinha UK, Saadat D, Doherty CM, Rice DH: Use of AlloDerm implant to prevent Freys syndrome after parotidectomy. Arch Facial Plast Surg 5: 109-12, 2003. [ Links ]

31. Prokopakis Emmanuel P., Vassilios A. Lachanas, Emmanuel S. Helidonis, George A. Velegrakis. The Use of the Ligasure Vessel Sealing Systemin Parotid Gland Surgery. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 2005;133:725-8. [ Links ]

32. Gutierrez A. Tumores de la glandula parotida. Su extripacion. Rev Cirugia 1923;3:23-7. [ Links ]

33. Ferreria JL, Maurino N, Michael E, Ratinoff M, Rubio E: Surgery of the parotid region: a new approach. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 48: 803-7, 1990. [ Links ]

34. Appiani A. Surgical management of parotid tumors. Revista Argentina de Cirugia 1967;21:236-9. [ Links ]

35. Bonanno PC, Palaia D, Rosenberg M, Casson P: Prophylaxis against Freys syndrome in parotid surgery. Ann Plast Surg 2000; 44: 498-501. [ Links ]

36. Casler JD, Conley J. Sternocleidomastoid muscle transfer and superficial musculoaponeurotic placation in the prevention of Freys syndrome. Laryngoscope 1991;101:95-100. [ Links ]

37. Meningaud JP, Bertolus C, Bertrand JC. Parotidectomy: assessment of a surgical technique including facelift incision and SMAS advancement. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2006;34:34-7. [ Links ]

38. Jost G, Guenon P, Gentil S: Parotidectomy: a plastic approach. Aesthetic Plast Surg 23: 1-4, 1999. [ Links ]

39. Zaoli G: Le comblement des de´ pressions re´ siduelles apre s parotidectomie par un lambeau compose´ arte´ riel sous-cutane´.Ann Chir Plast Esthet 1989;34: 123-7. [ Links ]

40. Ahmed OA, Kolhe PS: Prevention of Freys syndrome and volume deficit after parotidectomy using the superficial temporal artery fascial flap. Br J Plast Surg 1999;52: 256-60. [ Links ]

41. Wallis KA, Gibson T: Gustatory sweating following parotidectomy: Correction by a fascia lata graft. Br J Plast Surg 31:68, 1978. [ Links ]

42. Drobik C. Therapy of Frey syndrome with botulinum toxin A. Experiences with a new method of treatment. HNO. 1995;43:644-8. [ Links ]

43. Schulze-Bonhage A. Botulinum toxin in the therapy of gustatory sweating. J Neurol. 1996;243:143-6. [ Links ]

44. Bjerkhoel A. Freys syndrome: treatment with botulinum toxin. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;11:839-44. [ Links ]

45. Guntinas-Lichius O. Increased botulinum toxin type A dosage is more effective in patients with Freys syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2002;112: 746-9. [ Links ]

46. Blitzer A, Binder WJ, Brin MF. Botulinum toxin injection for facial lines and wrinkles: technique. In: Blitzer A, Binder WJ, Boyd JB, Carruthers A, eds. Management of Facial Lines and Wrinkles. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000:303-13. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en