Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Clínica y Salud

versión On-line ISSN 2174-0550versión impresa ISSN 1130-5274

Clínica y Salud vol.23 no.3 Madrid nov. 2012

https://dx.doi.org/10.5093/cl2012a13

Fostered Children´s Behavioural and Emotional Difficulties: Findings from one Independent Foster Care Agency

Las Dificultades Emocionales y de Comportamiento en los Niños Acogidos: Resultados de un Estudio en una Agencia Independiente de Acogimiento

Jo Staines1

1University of Bristol, UK

ABSTRACT

This paper documents the high levels of emotional and behavioural difficulties demonstrated by young people placed within a therapeutic fostering environment, and the provision of therapy for these difficulties. Whilst foster carers were positive about the support provided both to themselves and to the young people, there was no significant change in the levels of difficulties shown during the course of the study. Children showing higher levels of difficulty early in the placement were more likely to experience a placement disruption than those with lower levels of difficulty. The research suggests that it may be possible to identify those more likely to be at risk of placement disruption, using screening tools such as the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 1997). Furthermore, the research indicates that support mechanisms, including therapeutic interventions, for the foster carers and young people need to be implemented early to help stabilise and maintain these high-risk placements, and that delay in doing so may jeopardise the placement.

Key words: foster care, emotional and behavioural difficulties, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, therapeutic interventions.

RESUMEN

El presente trabajo pone de manifiesto la presencia de altos niveles de dificultades emocionales y de comportamiento en los niños y jóvenes que viven en acogimiento y la necesidad de promover terapias para gestionar estas dificultades. Si bien el apoyo que recibieron los niños en acogimiento fue muy positivo, no se hallaron cambios significativos durante el curso del estudio. Los niños que presentan los niveles más altos de dificultad en los primeros momentos del acogimiento fueron más propensos a experimentar perturbaciones que aquellos con niveles más bajos de dificultad. La investigación sugiere que es posible identificar a los niños en situación de riesgo, utilizando herramientas de detección, como el Cuestionario de Fortalezas y Dificultades (Goodman, 1997). Por otra parte, la investigación pone de manifiesto que los mecanismos de apoyo, incluyendo las intervenciones terapéuticas, necesitan ser implementados lo antes posible para contribuir a estabilizar y mantener estos acogimientos; una demora en hacerlo podría poner en peligro dicho acogimiento.

Palabras clave: acogimiento, Dificultades emocionales y conductuales, Cuestionario de Fortalezas y dificultades, intervenciones terapéuticas.

Introducción

Looked after children (LAC) are significantly more likely to experience psychiatric, emotional and behavioural disorders than children in the general population (Butler & Vostanis 1998; Garland et al., 2001; Meltzer, Corbin, Garward, Goodman, & Ford, 2003; Meltzer, Garward, Goodman, & Ford, 2000; Quinton rushton, Dance, and Mayes, 1998; Rubin, O´reilly, Luan, & Localio, 2007; Sempik, Ward, & Darker, 2008; Tarren-Sweeney, 2008; Whyte and Campbell, 2008). Ford, Vostanis, Meltzer, & Goodman, (2007) demonstrated that LAC have a higher prevalence of both psycho-social adversity and psychiatric disorder than the most socially and economically disadvantaged children living in private households - the high levels of psycho-social adversity perhaps influencing the development of some psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, even after excluding children with a recognised psychiatric disorder, less than 10% of LAC demonstrate particularly good, positive psychological adjustment, compared with approximately half of those living in private households (Ford, et al., 2007). Meltzer and colleagues (2003) found that 46% of LaC experienced a mental health or emotional disorder; using a different methodology and different assessment tools, Sempik and colleagues found that 72% of LAC had behavioural and emotional problems. These children require a formal assessment of emotional and behavioural well-being at the time of placement to identify their particular needs; if such needs are to be met, the provision of intensive, highly skilled support needs to be facilitated (Sempik et al., 2008).

Evidence suggests that children´s emotional and behavioural problems play a major part in placement stability, with poor mental health and disruptive behaviour being associated with placement disruptions (Sempik et al., 2008; Tarren-Sweeney, 2008; Ward, Holmes, Soper, & Olsen, 2008). In many cases, the mental health problems experienced by LAC pre-exist the young person´s entry to the looked after children system. However, a cyclical relationship also exists between placement instability and emotional and behavioural difficulties, with placement instability negatively affecting LAC´s mental health (Delfabbro and Barber 2003; Rubin et al., 2007). Given the link between emotional and behavioural difficulties, the stability of placements and poorer long-term outcomes for young people in care (Wilson, Sinclaire, Taylor, Pithouse, & Sellick, 2004; Sinclair 2005; Ward et al., 2008), it is important that children´s emotional and behaviour needs are assessed at the start of new foster placements so that carers can be prepared and appropriate services can be accessed (Turney, Platt, Selwyn & Farmer, 2011).

Improving the mental health of looked after children is therefore a priority for policymakers and practitioners, with Local authorities in Britain now being required to monitor the mental health of LAC, using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman, 1997; Department for Children, Schools and Families 2009a; Department for Education 2012; Goodman & Goodman, 2012). Other studies have also used the SDQ to estimate the prevalence of emotional and behavioural difficulties amongst LAC, which allow comparisons to be drawn. For example, Ford and her colleagues (2007) reported that 45% of LAC are shown by the SDQ to have a mental health or behavioural disorder, compared with approximately 10% of the general population (Goodman & Goodman, 2012). Similarly, Whyte and Campbell (2008) found that 40% of foster carers surveyed reported definite or severe difficulties, as measured by the SDQ, for the children in their care. This paper uses the SDQ and other measures to document the emotional and behavioural difficulties displayed by a sample of looked after children in one independent fostering agency in England.

Placing looked after children with mental health and behavioural difficulties with Independent Fostering Agencies

It is often difficult for Local authorities (LAs) in the United Kingdom to place and/or contain some children demonstrating high levels of mental health and behavioural difficulties, due to the costs and complexities of meeting their not inconsiderable needs. In the United Kingdom, some of these children will therefore be placed with Independent Fostering agencies (IFAs) who may be better able to meet their needs (Sellick, 2007). IFAs aim to address these emotional and behavioural difficulties by providing enhanced services such as therapy, educational provision and contact centres as part of their package of care (Sellick & Connolly, 2002; Sellick, 2002). Globally, there has been a gradual increase in out-sourcing, or externally commissioning, the provision of foster placements to non-governmental or independent fostering agencies (Laklija, 2011; Sellick, 2011). More specifically, there has been a wide proliferation of IFAs in England and Wales, with 33% of all foster placements in England (Department for Education, 2010) and over a quarter in Wales (Data Unit Wales, 2009) being provided by IFAs.

IFAs offer a range of support services for foster carers and young people in placements, and studies have shown that their carers are generally satisfied with the levels of support they receive, the fee and their professional recognition and status (Farmer et al., 2007; Kirton, Beechman, & Ogilvie, 2003; Ogilvie, Kirton, & Beechman, 2006). Many studies have emphasised the impact on carer retention and job satisfaction of consistent, high-quality support, combined with easy access to specialist help and reliable, close working relationships with social workers (Walker, Hill, & Triseliotis, 2002; Farmer, Moyers, & Lipscombe, 2004; Sinclair, Baker, Wilson, & Gibbs, 2005). However, whether children placed with IFAs do indeed have increased needs and difficulties for which carers need enhanced support, and whether these additional support services have an impact on placement stability, is less clear.

This paper reports on the levels of behavioural and mental health difficulties experienced by children and young people placed with an individual IFA and considers the therapeutic interventions and support services offered to these young people, whilst in placement. The overall aim of the study was to investigate the supports and services provided to the children and their carers, and to assess the relationship between these supports, the children´s progress and placement outcomes over a one-year period (Farmer et al., 2007; Staines, Farmer, & Selwyn 2011). The IFA studied had undertaken a comprehensive review of their systems for assessing children´s placement needs and providing therapy services with the intention of improving the quality and consistency of these elements within their "package". They had also laid increasing emphasis on the pivotal role of foster carers within the "parenting team" (consisting of a supervising social worker, Education Liaison Officer, Therapist and a resource Worker), with the aim of equipping carers to provide appropriate help for the child within a therapeutic home environment. The foster carers´ and IFa social workers´ views of the team parenting approach and the therapeutic framework are discussed in a related paper (Staines et al., 2011). This paper focuses more specifically on the levels of emotional and behavioural difficulties demonstrated by young people placed within this therapeutic fostering environment, including results from the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, and the provision of therapy for these difficulties. It also considers the relationship between emotional and behavioural difficulties displayed early in the placement, and longer-term placement stability.

Methodology

The study utilised a prospective, repeated measures design and was based on a consecutive sample of new placements of children, aged 5-14, placed by local authorities with one IFA over a year. Children aged under five, whose placements were likely to be unproblematic, and older adolescents who might leave their placements before the one-year follow-up, were excluded from the study, as were respite and bridging placements. The study received the approval of the independent ethics committee of the School for Policy Studies at the University of Bristol, and was also supported by the research Group of the association of Directors of Social Services (now the association of Directors of Children´s Services).

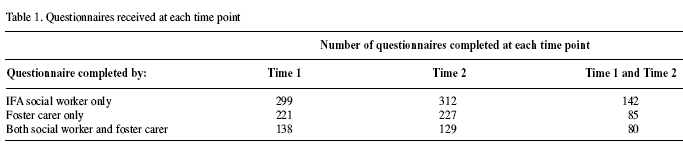

Every Local Authority in England and Wales which was making placements with the IFA was sent comprehensive information about the study; 23 LAs agreed to participate, allowing (with appropriate parental consent) contact to be made with children placed with the IFA. The IFA identified 450 children who met the sample criteria; they, their carers and the IFA social workers were sent start-of-placement questionnaires for completion (Time 1). Questionnaires were again sent out to carers, children and IFA social workers a year after the placement had started, or earlier if the placement had disrupted or ended in a planned move before then (Time 2). The number of questionnaires received at Time 1 and Time 2 are presented in Table 11.

Complete sets of questionnaires from both the IFA foster carers and social workers were received for only 138 placements at Time 1, which is just under a third (31%) of the placements included in the study. There were also only 80 placements for which complete sets of data were received from both social workers and carers at both Time 1 and Time 2, which makes identifying factors affecting the success of the placement difficult to isolate. The results are not representative of this IFA´s placements as they represent a limited proportion of all the placements during the year but the findings are important when considering and supporting placements for children with high levels of emotional and behavioural difficulties.

The Questionnaires

Most of the questionnaires were designed specifically for this study, and focused on the child´s strengths, difficulties and progress; the particular supports provided by the IFA and others, both to the child and their carers; changes taking place during the placement; and carer, social worker and child satisfaction. Of particular relevance to this paper, the study also utilised the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 1997), which is discussed in detail below.

The Fostered Children

The IFA social workers provided information about the characteristics and backgrounds of 299 children (132 girls [44%] and 167 boys [56%]) who entered an IFA placement during the study period. In accordance with the research design, the children were aged between five and 14 years at the time of the placement, with a median age of 12 years. A majority (87%) of the children were white, 6% were of mixed ethnicity, 5% black and 1% Asian. The children had started to be looked after at an average age of 8.7 years and had experienced an average of two episodes of care; for 52% the current episode of being looked after was their first, although they might have experienced more than one placement during this period. Just under three quarters (72%) of the children had had two or more (up to 15) foster placements, with just 28% of the children having been in their current foster home only.

The foster children´s backgrounds and difficulties prior to placement

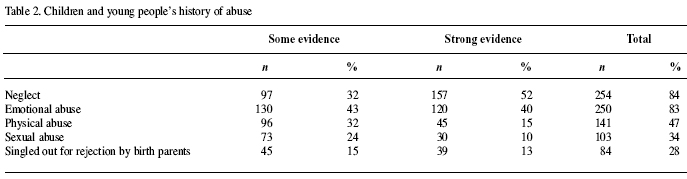

Most of the children were known to have experienced physical and sexual abuse, neglect and/or emotional maltreatment (Table 2; see also Tarren-Sweeney 2008). Furthermore, many of the children were recorded as having suffered more than one form of abuse. For example, of the 120 children for whom there was strong evidence of emotional abuse, 89 (74%) also experienced neglect and 31 (26%) rejection. Of those who had suffered sexual abuse, almost two thirds had also experienced emotional abuse and neglect.

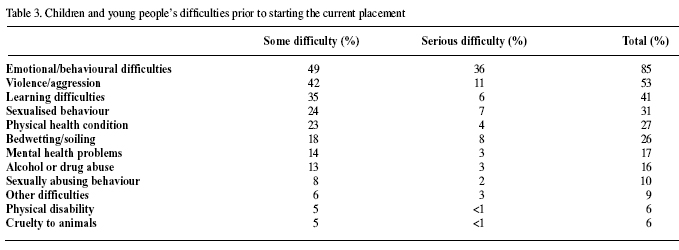

The high levels of psycho-social adversity experienced by many looked after children prior to their entry to care may explain the increased prevalence of some psychiatric disorders and emotional and behavioural difficulties (Ford et al., 2007; Stein, Evans, Mazumdar, & Rae-Grant, 1996; Tarren-Sweeney, 2008). Given their backgrounds, it is unsurprising that the children in this study presented a range of complex needs and difficult behaviour, with 95% of children displaying one or more of the difficulties listed in Table 3 prior to starting the current placement. Sempik and colleagues (2008) and Tarren-Sweeney (2008) report similarly high levels of prior psychosocial adversity and difficulties experienced by children prior to entry into the care system.

In the year prior to the study placement, three quarters (77%) of the children had shown either some (39%) or a lot (38%) of difficult behaviour either in the home or outside, with boys showing significantly more difficult behaviour than the girls. A quarter (26%) had been excluded from school in the year prior to the placement and a fifth had been reported to the police for offending.

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

The children and young people´s behavioural difficulties within the placement were assessed using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman, 1997). This is a well-validated screening and research instrument that measures whether children´s emotional and behavioural development is problematic or within a normal range. It is the most widely used instrument in child mental health research (Vostanis, 2006) and, as noted above, has recently been adopted by the Department for Education (2012; see also Department for Children, Schools and Families, 2009a) as a measure of the emotional and behavioural health of looked after children.

The SDQ has 25 items, 20 of which relate to four sub-scales on the most common areas of difficulty: emotional symptoms (anxiety and depression); conduct problems (oppositional or antisocial behaviour); hyperactivity; and peer problems. A fifth subscale relates to positive, prosocial behaviour, that is the extent to which a child is cooperative, friendly, helpful and gets on well with others (Goodman & Goodman, 2012). The sum of the sub-scale scores provides an overall "total difficulty" score, which ranges from 0-40. Both the total difficulty score and the sub-scale scores are standardized into well-validated bandings of "normal", "borderline" or "abnormal" (Goodman, 1997, Goodman & Goodman, 2011, 2012).

It is important to note that the SDQ cannot determine whether a child has a problem that ought to be "treated" or which would be classified as a psychiatric disorder. To do this, more detailed information would be collated from parents or carers, teachers and from the children or young people themselves. However, the SDQ used on its own does provide a reliable indication of the level and kind of difficulties that the children are currently experiencing. Moreover, many children have previously only received help when problems reached a level of "clinical significance", when difficulties are more entrenched and more intensive interventions are required (Whyte and Campbell 2008); it is more effective to intervene before difficulties become entrenched and potentially more severe (Turney et al., 2011). Providing earlier interventions to address difficulties before placements become fragile or vulnerable, may help children and carers find ways of coping with the difficulties, potentially reducing the likelihood of placement disruption and the costs and implications of providing longer-term interventions.

Data and Analyses

Carers completed Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaires in relation to 223 children and young people, aged between five and 14 years, at the start of the placement; SDQs were completed by carers in relation to 137 children 12 months later. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaires were also completed for 78 children who had moved once during the study period, and for five children who had moved twice, at the start of their new placements.

The total difficulty scores

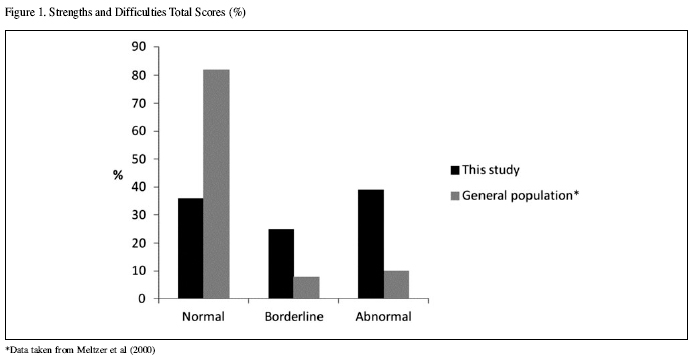

The mean total difficulty score within this study was 15.35 (range of 5 - 41, sd 4.795), compared with 13.9 in other research on looked-after children (DCSF, 2009b), and 8.4 in general population studies (Meltzer et al., 2000). The total difficulty scores re-classified into bands are shown in Figure 1; it is notable that almost two fifths (39%) of children demonstrated abnormal levels of difficulty, with a further 25% displaying borderline levels of difficulty, compared with only 10% and eight per cent respectively of general population samples (Goodman & Goodman, 2012).

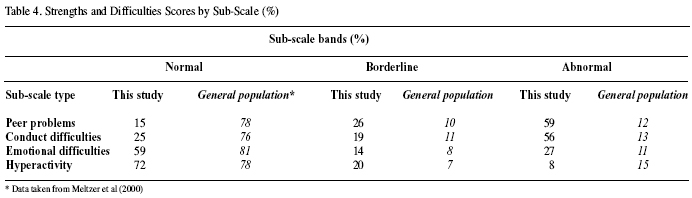

Sub-scales and types of problem

The total scores provide a rough guide on the level of psychiatric "caseness", that is, whether the child´s level of difficulty might indicate a clinically significant problem or disorder. The sub-scores give further detail on the specific problematic behaviour demonstrated by the children (Table 4), compared with data from general population studies (Meltzer et al., 2000).

The sub-scores for some areas may give higher proportions of difficulty than the total scores, which indicates that children may be showing clear difficulties in one area of psychosocial functioning, even if their total score is not in the abnormal range.

As can be seen from Table 4, over half (56%) of the children demonstrated abnormal conduct difficulties (including hot tempers and tantrums, fighting or bullying, lying or stealing), which reflects their earlier behavioural difficulties, highlighted in Table 3.

Abnormal emotional problems were less common than conduct difficulties but nevertheless affected just over a quarter of the children (27%), with a further 14% demonstrating borderline difficulties (Table 4). This is also true in studies in the general population where emotional problems are less prevalent than conduct difficulties (Meltzer et al., 2000). This may be due to how difficulties come to the attention of carers. Conduct problems are often outwardly expressed but emotional problems can be internalised and their outward signs can be more difficult to detect. Once again, emotional problems in these children are much more prevalent than they are in the general population.

Abnormal levels of peer problems were apparent in approximately three fifths (59%) of the children, with a further quarter (26%) showing borderline difficulties; indeed, only 15% of the children showed normal levels of peer difficulties, compared with 78% in general population samples (Meltzer et al., 2000).

Hyperactivity (over-active and distractible behaviour) was the least prevalent problem within this sample, with eight per cent of the children demonstrating abnormal levels of hyperactivity, and 20% showing borderline levels. These figures differ slightly from general population studies: the levels of normal hyperactivity in this study (72%) and Meltzer and colleagues´ (2000) study (78%) are not dissimilar. however, Meltzer and colleagues´ data suggests a higher level of abnormal hyperactivity in population samples (15%) and a lower level of borderline difficulty (7%). Farmer and colleagues (2007) argue that hyperactivity is usually underrecognised in social services data, even though it is amongst the most persistent problems and creates many difficulties in relationships with adults and with peers, as well as having serious implications for schooling.

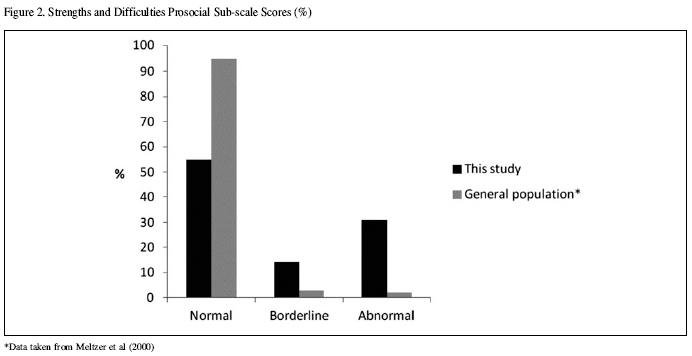

Prosocial behaviour

The SDQ also contains a sub-scale that reflects positive social qualities. As noted above, looked after children are less likely than those living in private households to demonstrate positive psychological adjustment (Ford et al., 2007). Approximately 95% of children in the general British population demonstrate normal positive social behaviour (Meltzer et al., 2000), compared with only 55% in this study (Figure 2).

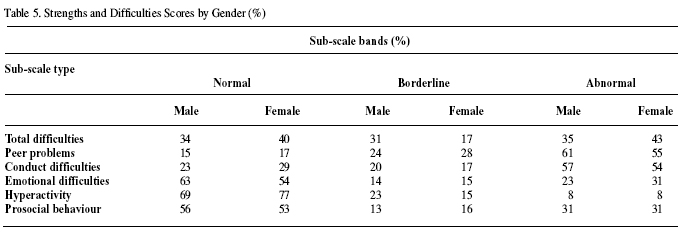

Gender differences in SDQ Scores

There were no statistically significant gender differences within the Total Scores, nor within the individual sub-scales - although the boys did demonstrate slightly higher levels of total difficulty, more conduct problems and more hyperactive behaviour. Girls demonstrated slightly higher levels of emotional problems (Table 5), although none of these differences were statistically significant. Other studies of looked after children have found that conduct problems are more common in boys and emotional problems more common in girls, especially in children in their teenage years (Sempik et al, 2008).

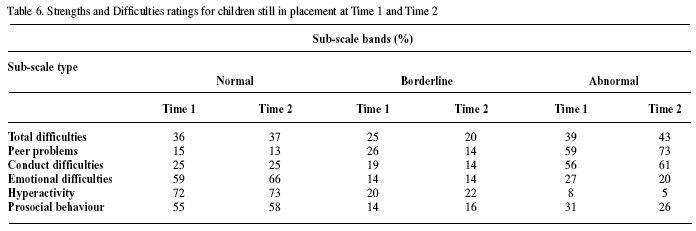

Changes in SDQ scores over time

This initial analysis of the carers´ ratings on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire reflected the high levels of problems in the children, with between a quarter and two fifths of children demonstrating problems in the abnormal range for all sub-scales except hyperactivity. Although there was some movement between borderline and abnormal bandings, particularly for peer problems, these levels did not change much during the course of the study; Table 6 shows the SDQ ratings for those children still in placement at Time 1 and Time 2. Other studies have shown that childhood psychopathology is often persistent, and ratings of children´s emotional and behavioural difficulties on the SDQ rarely change over a 12 month period (Goodman, Ford, & Meltzer, 2002).

The relationship between SDQ scores and placement stability/disruption is discussed below, after a consideration of the therapy provided to address the considerable needs faced by the young people and their careers.

The therapeutic environment and provision of therapy for behavioural difficulties

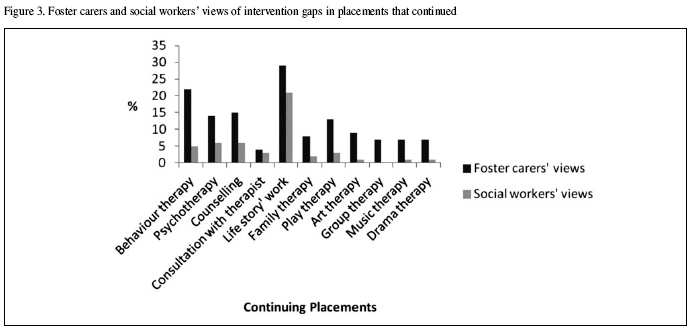

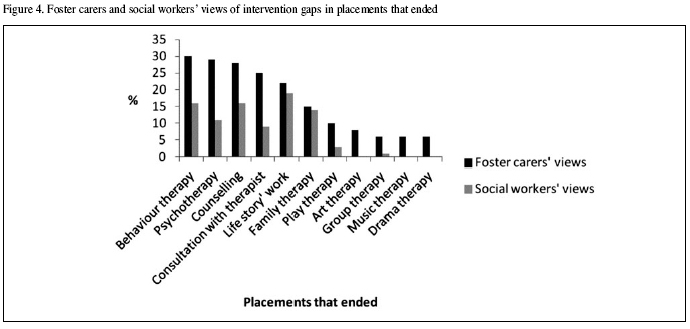

Although the British Government now requires local authorities to submit data on the total difficulties scores for looked after children, this may not happen until they have their statutory annual health assessment (Department for Education 2012), which may be some time after the start of their current placement. Within the particular IFA studied, consultations with the IFA therapist were planned much earlier to discuss the placement and the possible therapeutic needs of the child. Carers identified a range of therapeutic services that had already been provided and were useful, such as life story work, play therapy, and family therapy, although concerns remained that children needed therapeutic intervention that they were not receiving, particularly life story work (29%), and behaviour therapy (22%). These gaps in intervention are presented in Figures 3 and 4.

The main reasons for help not having been received were that a comprehensive assessment had not been completed (24%), or that help was planned but not yet in place (45%). Other reasons given by the foster carers for help not having been received included that the child had refused help, or the local authority had refused to fund therapy over and above the normal service provided by the IFA.

Whilst the majority (77%) of children in receipt of therapeutic support were considered by carers to have benefited from it, approximately half of the carers indicated that the child was in need of further support, suggesting that the therapeutic input was still not enough, or sustained for long enough, for some children. The IFA social workers were also asked about the support and therapy provided to the foster carer and child since the placement began. In particular, the provision of organised activities and consultations with the therapist were rated highly. The ratings of usefulness increased over time, indicating that these services took some time to make an impact.

There were some differences between the social workers´ and the foster carers´ views of the need for therapeutic intervention for some young people. For instance, the supervising social workers thought that life story work was still needed for a fifth (21%) of the children, but that other forms of therapy, such as behaviour therapy, counselling, and so forth were needed for less than six per cent of the children, far fewer than the carers thought (Figures 3 and 4). It might be that the carers have better knowledge of the needs of the young person, as they spend considerably more time with them, and so are better able to identify a need for intervention, or it could be that carers and social workers have different understandings of therapy and what it can achieve. If the latter, it might be necessary to provide foster carers with more information about the different forms of therapy available and what progress might realistically be made by a young person with and without therapeutic intervention.

The social workers indicated that the main reasons for support for the child not having been provided were that the assessment was not complete, help had been planned but not yet implemented, and funding difficulties. Disagreements with the local authority about funding or the long-term plan for the child could lead to delays in implementing necessary services, with potential detrimental effects on the child.

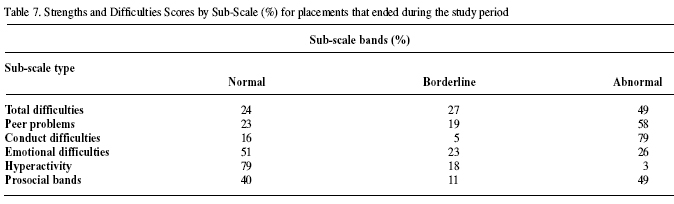

Placements that disrupted

During the study period, 147 children (33% of the 450 children for whom there was information) left the IFA, with about a third of these being planned moves and the remainder being placement disruptions. Seventy five foster carers returned questionnaires about the child´s placement following a move, including the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Table 7).

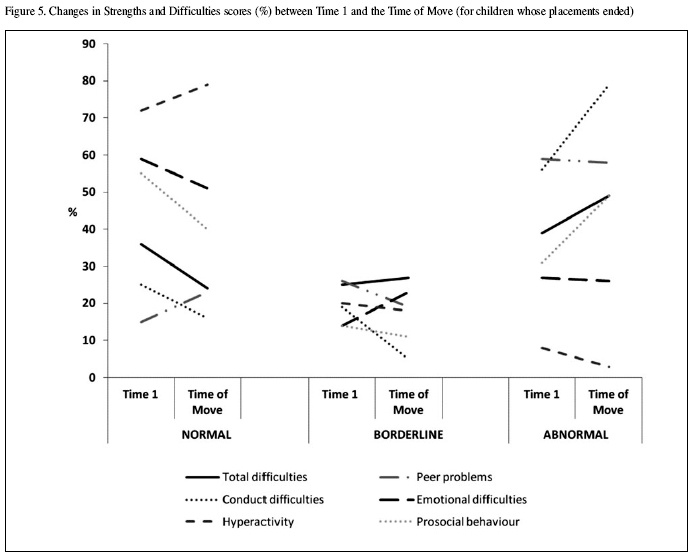

Again, as with the children who remained within their placements, there were no statistically significant changes in difficulties as measured by the SDQ between the start of the placement and the time of the placement ending, although there was a substantial increase in the level of abnormal conduct disorder, and abnormal prosocial behaviour; Figure 5 shows the change in scores on each of the SDQ sub-scales over time for children whose placements ended.

The carers said that conduct difficulties and children´s difficult behaviour were the main reasons for the move in a third of cases; other reasons for the placement ending included the child absconding, a breakdown in the relationship between the child and carer or other children in the household, and in one case because an allegation was made against the carers. Six per cent of the placements were ended due to local authority budgetary restrictions, for example social workers being placed under pressure to move children from the IFA to local authority foster placements, which were perceived to be less costly.

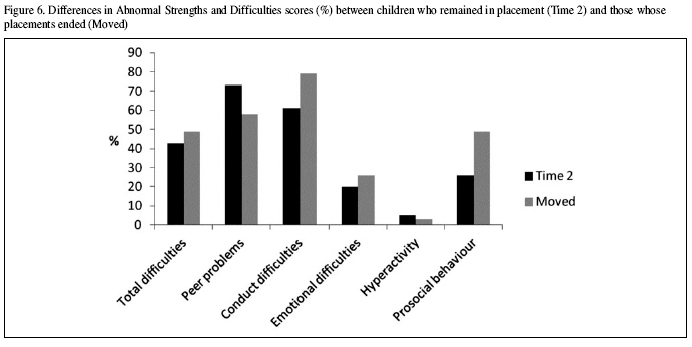

Again, although not statistically significant, there were some notable differences in SDQ scores between those children who remained in placement during the study period, and those who moved to a new placement. In particular, Figure 6 highlights higher levels of conduct disorder and poor prosocial behaviour in children whose placements ended. Interesting, higher levels of abnormal peer problems were more common in children whose placements continued than those whose placements ended during the study period, which suggests that carers did not find peer problems as difficult to manage.

Overall, children and young people who had higher levels of abnormal total scores on the SDQ (and in addition higher levels of abnormal subscores for conduct and peer problems) at Time 1 were significantly more likely to experience a placement disruption or move to a new placement during the course of the study. Sixty five per cent of the children and young people who experienced a placement disruption had total scores in the abnormal range at Time 1, compared with 49% of those who were still in placement at the time of follow up. This suggests it may be possible to identify those children and young people whose placements may be more fragile and be more likely to disrupt (in particular those with higher, or increasing, levels of conduct disorder), at an early stage in their placement so that appropriate support and interventions can be targeted effectively to those most at risk.

The number of carers and social workers who thought that some forms of therapy (particularly behaviour therapy, psychotherapy and family therapy) were needed but had not been provided was greater for children whose placements had ended than for those who were still in placement (Figure 4). It is difficult to isolate the reason for this: it could be that children whose placements ended early had more difficulties and therefore needed more therapeutic intervention, or that the lack of therapeutic intervention led to placements ending sooner than anticipated (see also Ford et al., 2007). Either way, this highlights the need for the early identification of emotional and behavioural difficulties, and the rapid provision of therapeutic interventions or other assistance for children with high levels of difficulty.

Conclusions and Implications for Practice

The findings of this study demonstrate that the disrupted and disadvantaged backgrounds of the young people and their resultant difficulties and challenging behaviour appear to warrant the additional support provided within the IFA´s "therapeutic" placements. The foster carers, supported by each element of the parenting team - the supervising social worker, the Education Liaison Officer, the Therapist and the resource Worker - provided high quality placements for many of the challenging children who were placed with the IFA, although the most disturbed children were at higher risk of placement breakdown. although this was a relatively small scale study, which makes statistical relationships difficult to identify, there were indications that such children could be identified using the SDQ as those with higher levels of total difficulties, in particular conduct disorder, were more at risk of their placement ending during the study period. Whilst there are some uncertainties about the reliability of foster carers´ reports of children´s problems, there is also evidence that carers are at least as reliable as parents (Tarren-Sweeney et al., 2004), and as such their views of children´s difficulties should be given due consideration by professionals working to support these challenging placements.

As already noted, the Government in England has provided guidance suggesting that the SDQ should be completed with all newly-placed children (Department for Children, Schools and Families, 2009a), although this is a recommendation not a requirement; perhaps if every child was assessed via the SDQ at the start of the placement (as also recommended by Whyte and Campbell, 2008) - by both the carer and the social worker - the carers and social workers would have a shared understanding of the needs of the young person. This could reduce the discrepancy between the social workers´ and the foster carers´ views of the need for therapeutic intervention for some young people, as well as identifying to the placing local authorities the need for additional services.

However, some caution is needed - this approach would entail considerably more assessment work, with its associated costs and implications (Turney et al., 2011). Furthermore, social workers should be cautious about the level of accuracy that can be achieved using tools such as the SDQ and not place undue reliance on actuarial methods of assessment. The SDQ itself also does not measure attachment and attachment behaviours, which are known to also impact on placement stability for LAC (Schofield and Beek 2009); attachment difficulties therefore also need to be taken into account when making and supporting foster placements. However, when used judiciously, tools such as the SDQ can play an important part in the assessment of children´s mental health needs, and inform a broader holistic assessment of the child´s situation (Turney et al,. 2011).

A number of the shortfalls illustrated by these findings were located at the intersection between the foster care provider and the local authority children´s services that placed the children. For example, delays in decision-making or a lack of longterm planning could hinder the provision of services and therapy. Consideration needs to be given by both independent agencies and local authorities as to how they can assist and promote inter-agency working, to ensure that services are not delayed. There are also difficult negotiations to be held over the funding of services. Good outcomes for children are likely to be enhanced in the context of a professional culture of good communication and information sharing (Turney et al., 2011).

The IFA social workers´ and carers were critical of the local authorities´ "refusal" to pay for therapeutic intervention, yet clearly local authorities do have a limited budget and may already consider themselves to be paying over the odds for an independent foster care placement. However, the high levels of behavioural and emotional difficulties evidenced in this research, and in other studies, emphasise the need for the early, thorough assessment of looked after children´s mental health problems. The provision of long-term specialist support, addressing these needs, could contribute to reducing placement instability and disruptions, proving to be cost-effective in the long run.

1 n therefore varies according to which dataset is being analysed at each time point.

Referencias

1. Butler, J., & Vostanis, P. (1998). Characteristics of referrals to a mental health service for young people in care. Psychiatric Bulletin, 22, 85-87. [ Links ]

2. Data Unit Wales. (2009). Children Looked After by Local Authorities in Foster Placements at 31 March 2008, Retrieved from http://dissemination.dataunitwales.gov.uk/webview/index.jsp [ Links ]

3. Delfabbro, P. h., & Barber, J. G. (2003). Before it´s too late: Enhancing the early detection and prevention of long-term placement disruption, Children Australia, 28, 2, 14-18. [ Links ]

4. Department for Children, Schools and Families. (2009a). Statutory Guidance on Promoting the Health and Well-being of Looked After Children, London: DCSF. [ Links ]

5. Department for Children, Schools and Families. (2009b). Children Looked After in England (including adoption and care leavers) year ending 31 March 2009, London: DCSF. retrieved from http://www.education.gov.uk/rsgateway/DB/SFR/s000878/index.shtml [ Links ]

6. Department for Education. (2010). Children Looked After by Local Authorities in England - year ending 31 March 2010, London: Office for National Statistics. [ Links ]

7. Department for Education. (2012). Children in Care: Promoting health and well-being, London: DfE. retrieved from http://www.education.gov.uk/childrenandyoungpeople/families/childrenincare/a0065777/promoting-health-and-wellbeing [ Links ]

8. Farmer, E., Moyers, S., & Lipscombe, J. (2004). Fostering Adolescents, London: Jessica Kingsley. [ Links ]

9. Farmer, E., Selwyn, J., Quinton, D., Saunders, H., Staines, J., Turner, W., & Meakings, S. (2007). Children Placed with an Independent Foster Care Provider: Experiences and progress, Bristol: hadley Centre for adoption and Foster Care Studies, School for Policy Studies, University of Bristol. [ Links ]

10. Ford, T., Vostanis, P., Meltzer, h., & Goodman, r. (2007). Psychiatric disorder among British children looked after by local authorities: comparison with children living in private households, British Journal of Psychiatry, 190, 319-325. [ Links ]

11. Garland, A. F., Hough, R. L., McCabe, K, M., Yeh, M., Wood, P. A., & Aarons, G. A. (2001). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in youths across five sectors of care. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 409-418. [ Links ]

12. Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A Research Note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 581-586. [ Links ]

13. Goodman, R., Ford, T., & Meltzer, h. (2002). Mental health problems of children in the community: 18 month follow up. British Medical Journal, 324, 1496-1497. [ Links ]

14. Goodman, A., & Goodman, R. (2011). Population mean scores predict child mental disorder rates: validating SDQ prevalence estimators in Britain. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 100-108. [ Links ]

15. Goodman, A., and Goodman, R. (2012). Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire scores and mental health in looked after children. British Journal of Psychiatry, 200, 426-427. [ Links ]

16. Kirton, D., Beecham, J., & Ogilvie, K. (2003). Remuneration and Performance in Foster Care: Final report, Canterbury: University of Kent. [ Links ]

17. Laklija, M. (2011). Foster care models in Europe: Results of a conducted survey. Zagreb: Forum, Retrieved form http://www.esn-eu.org/e-newsnov11-foster-care-models-in-europe/index.htm [ Links ] 18. Meltzer H, Corbin T, Gatward R, Goodman R., & Ford, T. (2003). The Mental Health of Young People Looked After by Local Authorities in England. London: The Stationery Office. [ Links ] 19. Meltzer, H., Gatward, R., Goodman, R., & Ford, T. (2000). Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in Great Britain. London: The Stationery Office. [ Links ] 20. Ogilvie, K., Kirton, D., & Beecham, J. (2006). Foster carer training: resources, payment and support. Adoption and Fostering, 30 (3), 6-16. [ Links ] 21. Quinton D., Rushton A., Dance C., and Mayes D. (1998). Joining New Families: a Study of Adoption and Fostering in Middle Childhood. Chichester: Wiley. [ Links ] 22 Rubin, D. M., O´reilly, A. L. R., Luan, X., & Localio, A. R. (2007). The impact of placement stability on behavioral well-being for children in foster care, Pediatrics, 336-344. [ Links ] 23. Schofield, G., & Beek, M. (2009). Growing up in foster care: providing a secure base through adolescence, Child and Family Social Work, 14, 255-266. [ Links ] 24. Sellick, C. (2002). The aims and principles of Independent Fostering Agencies: a view from the inside. Adoption and Fostering, 26, 1, 56-63. [ Links ] 25. Sellick, C. (2007). Towards a mixed economy of foster care provision. Social Work and Social Sciences Review, 13, 25-40. [ Links ] 26. Sellick, C., & Connolly, J. (2002). Independent fostering agencies uncovered: The findings of a national study. Child and Family Social Work, 7, 107-120. [ Links ] 27. Sempik, J., Ward, H., & Darker, I. (2008). Emotional and behavioural difficulties of children and young people at entry into care, Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 13, 221-233. [ Links ] 28. Sellick, C. (2011). Privatising Foster Care: the UK experience within an international context. Social Policy and Administration, 45, 788-805. [ Links ] 29. Sinclair, I. (2005). Fostering Now: Messages from research, London: Jessica Kingsley. [ Links ] 30. Sinclair, I., Baker, C., Wilson, K., & Gibbs I. (2005). Foster Children: Where they go and how they get on, London: Jessica Kingsley. [ Links ] 31. Stein, E., Evans, B., Mazumdar, R., & Rae-Grant, N. (1996). The mental health of children in foster care: a comparison with community and clinical samples. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 41, 385-391. [ Links ] 32. Staines, J., Farmer, E., & Selwyn, J. (2011). Implementing a Therapeutic Team Parenting approach to Fostering: The Experiences of One Independent Foster-Care agency. British Journal of Social Work, 41, 314-332. [ Links ] 33. Tarren-Sweeney, M. (2008). Retrospective and concurrent predictors of the mental health of childrenin care. Children and Youth Services Review, 30, 1-25. [ Links ] 34. Tarren-Sweeney, M. J., Hazell, P. L., & Carr, V. J. (2004). Are foster parents reliable informants of children´s behaviour problems? Child: Care, Health and Development, 30, 167-175. [ Links ] 35. Turney, D., Platt, D., Selwyn, J., & Farmer, E. (2011). Social Work Assessment of Children in Need: What do we know? Messages from Research, London: Department for Education. [ Links ] 36. Vostanis, P. (2006). Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: research and clinical applications. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 19, 367-372. [ Links ] 37. Walker, M., Hill, M., & Triseliotis, J. (2002). Testing the Limits of Foster Care: Fostering as an alternative to secure accommodation. London: BAAF. [ Links ] 38. Ward, H., Holmes, L., Soper, J., & Olsen, R. (2008). Costs and Consequences of Placing Children in Care, London: Jessica Kingsley. [ Links ] 39. Whyte, S., & Campbell, A. (2008). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a useful screening tool to identify mental health strengths and needs in looked after children and inform Care Plans at Looked after Children reviews? Child Care in Practice, 14, 193-206. [ Links ] 40. Wilson, K., Sinclair, I., Taylor, C., Pithouse, A., & Sellick, C. (2004). Fostering Success: An exploration of the research literature on foster care. London: Social Care Institute for Excellence. [ Links ] Artículo Recibido: 18/07/2012 ![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Jo Staines

e-maill: jo.staines@bristol.ac.uk

Revisión Recibida: 13/08/2012

Aceptado: 20/08/2012