INTRODUCTION

Physical activity, conceived as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure” (Caspersen, Powell, & Christenson, 1985) is related with many health benefits in school-aged children and youth (Janssen & LeBlanc, 2010), being a protective factor against mental health problems as well as a way to improve cognitive functioning (Biddle & Asare, 2011). Likewise, sport practice, defined as "all forms of physical activity which, through casual or organised participation, aim at expressing or improving physical fitness and mental well-being and forming social relationships, or obtaining results in competition at all levels" (Council of Europe, 2001), also is associated to different psychological, social and health benefits, as self-esteem improvement, social interaction and fewer depressive symptoms (Eime, Young, Harvey, Charity, & Payne, 2013). Further, maintaining these active and healthy behaviours during early life stages, may influence future behaviours and health status in adulthood (Ortega, Ruiz, Castillo, & Sjöström, 2008).

Despite the broad evidence with regard to the benefits linked to physical activity and sport practice, levels of moderate-to-vigorous exercise are alarmingly low among occidental adolescents (Marques & Matos, 2014). According to latest survey from Health behaviour in school-aged children study (Inchley et al., 2016), only 21% of 11-, 13- and 15-year-old adolescents meet the current guidelines that have been established by different institutions, as WHO or “USA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention”: at least 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity at least five times a week. Spain is slightly above the average, with 27% of teenagers complying with such recommendations. Furthermore, there are significant gender differences in this percentage in Spain, since the 34% of boys met the guidelines, while only the 19% of girls did. These differences represent a general trend indicated in numerous studies (Aibar et al., 2013; Peiró-Velert, Devís-Devís, Beltrán-Carrillo, & Fox, 2008). A recent study by Beltran Carrillo et al. (2017) has found gender differences in time spent by adolescents in sedentary or physical activity in different segments of a normal day. They have assessed with accelerometers the physical activity in a sample of Spanish adolescents, and concluded that boys presented more vigorous physical activity during school time, weekday afternoons and evenings, and also during weekend. Girls showed more sedentary time during weekday evenings. Other research with Spanish adolescents has indicated some gender differences in the type of extracurricular activities (Codina, Pestana, Castillo, & Balaguer, 2016). Its results indicated that girls dedicate time out of school to dance and study, while boys prefer doing team sports. Boys were found to spend doubled time to practice team sports compared to girls.

There is a growing body of literature suggesting that higher physical activity and sports participation are associated to better mental health. Most of this evidence has been proved with adult samples. Bize, Johnson, and Plotnikoff (2007) performed a systematic review of cross-sectional studies which concluded that self-reported physical activity was positively related to health related quality of life (i.e., positive perceptions of both physical and mental health). The number of studies indicating that physical activity improves mental health among adolescents has raised (Valois et al., 2004; Hallal et al., 2006). In this regard, adolescents who report being active have a decreased likelihood to suffer from mental health problems (Biddle & Asare, 2011), as the presence of depressive symptoms (Motl et al., 2005). In a sample of Spanish adolescents, Herrera-Gutierrez, Brocal-Perez, Sanchez Marmol, and Rodriguez Dorantes (2012) showed that higher frequency of physical activity was associated with less depressive and anxious symptoms. In the same way, some studies have shown that subjective well-being, understood as people´s cognitive and affective evaluations of their lives, and considered the positive component of mental health (Diener et al., 2003), is positively associated with regular practice of physical activity among adolescents, both cross-sectionally and longitudinally (Bartels et al., 2012). A recent cross-sectional study with a sample of 11,110 adolescents from ten European countries has indicated that only 17.9% of boys and a 10.7% of girls reported sufficient physical activity based on WHO guidelines, and that higher frequency of activity was positively related with well-being (McMahon et al., 2017). These findings may be of significant relevance in adolescence, given that subjective well-being development has the potential to improve functioning not only in the sphere of academics, but also in other critical domains of life, such as personal relationships, contributing to success and fulfilment throughout the lifespan (Bird & Markle, 2012).

Life satisfaction, defined as a global assessment by the person of the quality of his or her life (Pavot, Diener, Colvin, & Sandvik, 1991), is commonly defined as a cognitive aspect of subjective well-being, being considered the most stable subjective well-being´s component over time (Park, 2004). This construct is closely related to mental health (Pavot & Diener, 2008), conceived in positive terms and not as the mere absence of mental disorders. Nevertheless, life satisfaction can also contribute to the prevention of mental illnesses as depression, given that several studies have reported an inverse association between both variables (Koivumaa-Honkanen, Kaprio, Honkanen, Viinamäki, & Koskenvuo, 2004; Mahmoud, Staten, Hall, & Lennie, 2012). In the last few years, greater attention has been paid to life satisfaction assessment among children and adolescents. Specifically, across the adolescence, life satisfaction plays an important role in developmental processes, facilitating social relationships and preventing the onset of psychological disorders and unhealthy habits (Valois, Zullig, Huebner & Drane, 2004). According to Suldo and Huebner (2005), adolescents with higher life satisfaction scores show better mental health as well as improved social, intrapersonal and cognitive functioning. Research has underlined substantial gender differences in psychological adjustment during adolescence, with adolescent girls showing more internalizing symptoms, i.e., anxious and depressive symptoms (Derdikman-Eiron et al., 2011; Wade, Cairney, & Pevalin, 2002). This gender differences posits girls in a greater vulnerability to suffer mental disorders in adulthood (Lewinsohn, Rohde, Klein, & Seeley, 1999).

Study Justification and Aim

Because of the relevance of life satisfaction during adolescence, an understanding of those factors that may have a positive effect on it is required. More research is needed in order to guide the design of intervention programs by health care or educational organizations aimed to develop adolescent life satisfaction. In this regard, physical activity and sport participation may be important factors that help increase life satisfaction during this life stage, since the results from many different studies which were carried out with adolescents show that physical and sport activity were associated with increased life satisfaction (Paupério, Corte-Real, Dias, & Fonseca, 2012; Zullig & White, 2011). Data from the ultimate HBSC study supported this relationship, adding an age decrease in both physical activity and life satisfaction (Inchley et al., 2016).

Furthermore, gender differences have been observed in relation to the association between physical exercise and well-being. The studies of Brooks et al. (2014) and Zullig and White (2011) indicated a significant positive relationship between vigorous physical activity in the leisure time and life satisfaction in girls, but not in boys. Similarly, Valois et al. (2004) reported gender differences, so that significant association between dissatisfaction with life and not playing in sport teams run by organizations outside of school was found among white girls, but not in white boys. Moreover, significant relationships between dissatisfaction with life and not exercising for at least 20 minutes in the past seven days and not performing exercise to strengthen or tone muscles were established among white males, but not in white females.

Notwithstanding all these results could suggest that the decrease in physical activity through adolescence would affect life satisfaction, although the cross-sectional design of the majority of these studies makes inferring directionality not possible. To our knowledge, only the HUNT study by Rangul et al. (2012) has examined the impact of physical activity on life satisfaction over time among adolescents. The sample was composed by 1,869 Norwegian participants who were assessed both in adolescence (aged 13 to 19) and young-adulthood (aged 23 to 31). Rangul et al. (2012) concluded that those adolescent girls who reported being active both in adolescence and early adulthood showed a increased probability of being satisfied with life ten years later compared to those who were adopters (i.e., inactive as adolescents and physically active as young adults). In boys, those who were active in both adolescence and young adulthood reported better mental health (i.e., lower depression scores) than those who were adopters.

Given the paucity of research that have addressed the association between physical activity or sport participation and life satisfaction from a longitudinal perspective in adolescence, more research is required. Moreover, further examination of gender differences in this association is also recommended. Thus, the main purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between physical and sport activity and life satisfaction over a period of one year in middle adolescents from Southern Spain, by examining gender differences. We expect to provide evidence for the prospective positive effect of physical activity and sport participation on adolescents´ mental health, especially in girls.

METHODS

Overall Study Design and Data Collection

A prospective cohort study was carried out, in which a sample of participants from different age cohorts was evaluated one year later (Ato, Lopez, & Benavente, 2013). In this panel design, the whole sample participated in two assessments separated by one year of the satisfaction with life (i.e., dependent variable), while sport participation and physical activity practice (i.e., independent variables) were only measured in the first assessment. This longitudinal design allows to establish relationships between antecedents (i.e., sport and physical activity in time 1) and consequences (i.e., life satisfaction in time 2), controlling for initial values in the criterion variable (i.e., life satisfaction in time 1), and examining differences by age cohorts.

The first assessment of the study was conducted in April and May of 2011, while the second one was carried out one year later. For data collection, a paper-based self-report was individually and anonymously administered in each classroom. A code was created with the number of high school (1-19), birth date (day, month and year), and gender (1 boy, 2 girl), in order to allow the tracking and maintain anonymity. No student refused to participate in the study and omissions were below 0.5% in each separate. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study and their parents, and all procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of Helsinki declaration. This research obtained approval from university ethical board.

Participants

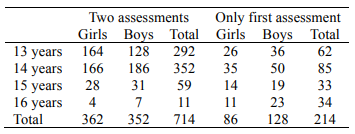

A total of 714 adolescents (50.7% girls), aged between 13 and 16 years old (M = 13.70, SD / .68) participated in this longitudinal research. They were enrolled in grades 7 and 8 in a convenience sample of 19 Secondary Education schools in Andalusia (Southern Spain). The selection was controlled to include Secondary Education schools which presented different ownership (5 were public and 14 were private) and were located in different habitats (21% rural, 21% semi-urban, 32% urban and 26% large city). After selecting each secondary school, participating classes were randomly selected. In 2010, the adolescent population aged 13-16 years old in Andalusia was 361,622 (Observatorio de la Infancia en Andalucía, 2011). The sample size was calculated with a confidence level of 99% and a margin of error of 5%, thus recommending a size of at least 665 participants.

The initial sample was composed by 928 adolescents at the beginning of the study in the first assessment. Thus, up to the 77% of this initial sample maintained its participation after the follow-up, and a total of 218 adolescents only completed the first assessment. The attrition rate was probably due to participant lack of attendance to class the day or time assigned to the fieldwork in each school, or a change of school to another non-participating one in this research. Table 1 presents the frequency distribution by age and gender of the final sample of participants with two assessments, compared to participants who did not complete the second assessment. Attrition analyses were performed to examine differences in demographics and study variables in time 1 between the final sample and the participants who did not complete the second assessment. The sample of participants who did not completed the second assessment presented a greater percentage of boys (59.8%), χ2(1, N = 928) = 7.29, p = .007, and a higher mean age (M = 14.18, SD / 1.03), t(926) = 7.91, p < .001. Moreover, these participants who did not complete the study showed lower life satisfaction in time 1 (M = 17.60, SD / 5.05) than the final sample of the longitudinal study (M = 18.80, SD / 4.51), t(912) = -3.28, p = .001. No significant differences were observed in sport participation in time 1, χ2(4, N = 926) = 8.93, p = .063, nor in the practice of physical activity in time 1, χ2(5, N = 924) = 2.78, p = .734. By conducting listwise deletion, only cases with the two assessments were included in the subsequent analyses (N = 714), because sample size was big enough to secure adequate statistical power. Following recommendations by Kristman, Manno, and Côté (2005), only with a percentage of attrition over 25%, missing values not at random would produce problematic estimates under the complete subject analysis.

Instrument

activity and sport participation. Two questions to measure sport practice and physical activity outside school time, validated by HBSC study (Wold et al., 1993; Mendoza et al., 1994), were administered in Time 1. The first item asked "How often do you practice some sports or gymnastics during out-of-school time?" and proposed five Likert-type response options (never, rarely, one day a week, several days a week but not every day, and every day). The second item says: "How many hours a week do you usually make some physical activity during out-of-school time?, and presents six Likert-type response options (none, about half an hour, about one hour, about 2-3 hours, about 4-6 hours, more than 7 hours).

Overall life satisfaction. The Spanish adolescent validation (Atienza, Pons, Balaguer, & Garcia-Merita, 2000) of Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985) was used in both time 1 and 2, in order to obtain a valid and reliable measure of the adolescents' global life satisfaction. This scale is composed of 5 items (e.g., "I am satisfied with my life" and "The conditions of my life are excellent") with 5 Likert-style response options, from "strongly agree" to "strongly disagree". The total score is calculated by adding the score for the 5 items, and ranges between 5 and 25. A higher score in scale means a higher life satisfaction. Notable internal consistency reliability was detected in both wave 1 (α = .85) and wave 2 (α = .88).

Data Analysis Design

Little test indicated that missing values of the variables in the final sample were distributed completely at random, χ2(13, N = 714) = 17.15, p = .192. A maximum likelihood imputation procedure, based on expectation-maximization algorithm, was conducted to deal with missing values.

First, gender and age differences in sport participation and physical activity in time 1 were calculated by χ2 tests. Gender and age differences in life satisfaction in times 1 and 2 were analyzed by Student-T tests and variance analysis. Second, repeated measures variance analyses were conducted in order to study changes in life satisfaction, analyzing the role of sport and physical activity in time 1 and attending to possible gender differences. These analyses were performed with SPSS 21.0.

Finally, a structural equation model tested the relationship between sport and physical activity in time 1 with life satisfaction in time 2, controlling initial levels of life satisfaction and by gender. To test the overall goodness of fit in the model, robust Satorra-Bentler χ2 was calculated. Because this statistic is very sensitive to sample size, the ratio of χ2 value and degrees of freedom was analysed, reaching a good fit when this ratio presents a value lower than 3. Furthermore, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) were analysed. These indicators would report a good fit with values lower than 0.08. The value of the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) was also analysed, which would inform a good fit with values above 0.95 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). In addition, particular attention was given to standardised residuals and measurement equations. Structural equation modelling analyses were conducted using EQS 6.1.

RESULTS

Gender and Age Differences in Sport Participation, Physical Activity and Life Satisfaction

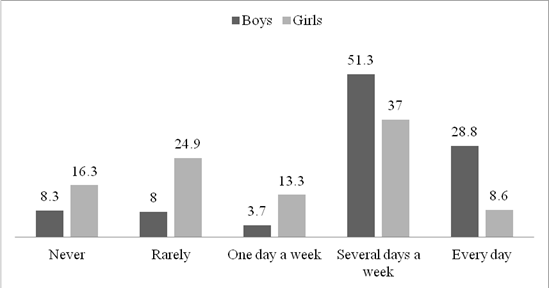

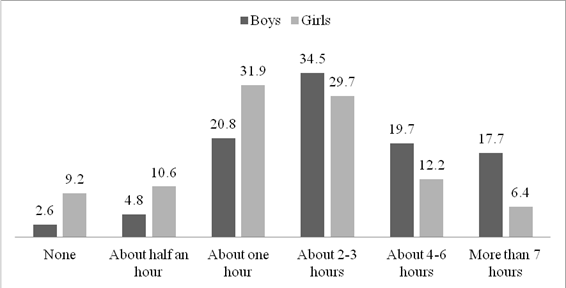

Concerning sport participation in time 1, results indicated that boys practiced sport more frequently than girls, χ2(4, N = 714) = 106.60, p < .001, V = .39. Only 16.3% of boys never or rarely practiced sport, while this percentage was higher in girls, 41.2%. Furthermore, 80.1% of boys reported they played sports several days a week or every day, compared to 45.6% of girls (see Figure 1). Boys also presented higher physical activity than girls in time 1, χ2(5, N = 714) = 55.30, p < .001, V = .28. About 51.7% of girls presented one hour or less of physical activity per week, while only 28.2% of boys reported it. If 37.4% of boys indicated that they made physical activity more than 4 hours a week, in girls this percentage was 18.6% (see Figure 2). No age differences were detected in sport participation, χ2(12, N = 714)= 16.23, p = .181, nor in physical activity, χ2(15, N = 714) = 16.63, p = .342.

Regarding life satisfaction, no gender differences were found in time 1, t(712) = .12, p = .904, nor in time 2, t(712) = 1.73, p = .084. Significant age differences were observed in time 1: 13-year old adolescents presented higher life satisfaction (M = 19.25, SD / 4.39) than adolescents aged 14 (M = 18.79, SD / 4.46), 15 (M = 16.67, SD / 4.76) and 16 years old (M = 18.63, SD / 3.32), F(3, 710) = 5.51, p = .001, ɳ2p = .023. However, no differences were found in time 2, F(3, 710) = .931, p = .425.

Change in Life Satisfaction, by Gender, Sport Participation and Physical Activity

A significant but short decrease was detected in life satisfaction from time 1 (M = 18.80, SD / 4.48) to time 2 (M = 18.35, SD / 4.41), F(1, 713) = 6.69, p = .010, ɳ2p = .01. Sport participation in time 1 presented a significant inter-subject effect on life satisfaction, F(4, 708) = 4.48, p = .002, ɳ2p = .02. Thus, higher sport participation was associated with higher life satisfaction in both waves of the study. When this inter-subject effect was studied by gender, results indicated that only in girls sport participation was significantly associated with life satisfaction, F(4, 357) = 2.88, p = .023, ɳ2p = .02, but not in boys, F(4, 346) = 1.64, p = .164. Adolescent girls who never (M = 18.27, SD / 4.34) or rarely (M = 17.86, SD / 4.87) participated in sport activities in time 1 presented lower life satisfaction in time 1 than girls who practiced sport several days a week (M = 19.43, SD / 4.14). Moreover, girls who never (M = 17.45, SD / 4.27) or rarely (M = 17.31, SD / 4.55) practiced sport in time 1 reported higher life satisfaction in time 2 than adolescent girls who played sports several days a week (M = 18.93, SD / 4.35).

Regarding physical activity in time 1, a significant inter-subject effect was also found on life satisfaction, F(5, 705) = 4.11, p = .001, ɳ2p = .03. In the same line than sport participation, when the inter-subject effect of physical activity on life satisfaction was analysed by gender, results showed that only in girls that effect proved significant, F(5, 354) = 3.33, p = .006, ɳ2p = .05, but not in boys, F(5, 345) = 2.05, p = .071. Thus, adolescent girls who indicated that they practiced physical activity between 4 and 6 hours a week (M = 20.52, SD / 3.93) were more satisfied with their lives in time 1 than girls who indicated no physical activity (M = 17.55, SD / 4.32) or about half an hour per week (M = 18.05, SD / 4.78). Regarding life satisfaction in time 2, girls who reported physical activity between 4 and 6 hours per week (M = 19.82, SD / 4.40) were more satisfied with their lives one year later than adolescent girls who did not make any physical activity (M = 15.88, SD / 5.28).

Structural Equation Model

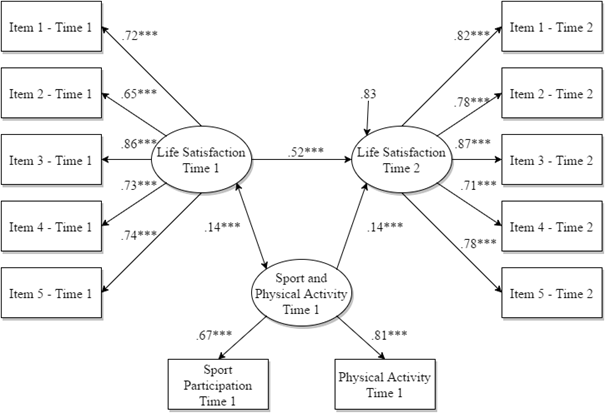

A structural equation model was developed in order to test the relationship between sport participation and physical activity with life satisfaction one year later, controlling baseline scores in life satisfaction. Thus, three factors were developed: one factor for "Life Satisfaction in Time 1", composed of its respective 5 indicators, other factor for "Life Satisfaction in Time 2", also integrated by its 5 items, and a third factor called "Sport and Physical Activity in Time 1", which was composed of the score in sport participation in time 1 and the score in physical activity in time 1. Firstly, two confirmatory factor analyses were conducted to check the validity of life satisfaction measure in each assessment time. The factor "Life Satisfaction in Time 1" was significantly composed of its 5 items, as the model reached good overall data fit, Satorra-Bentler χ2(4, N = 714) = 6.55, p = .162, CFI = .997, SRMR = .022, RMSEA = .030, 90% CI RMSEA = .000 - .069, and all measurement equation were significant. Standardised residuals were very low (between -0.1 and 0.1). The confirmatory factor analysis of "Life Satisfaction in Time 2" also presented good data fit, Satorra-Bentler χ2(4, N = 714) = 6.88, p = .142, CFI = .998, SRMR = .013, RMSEA = .032, 90% CI RMSEA = .000 - .071. All measurement equation proved significant and standardised residuals were between -0.1 and 0.1. Furthermore, the score in sport participation in time 1 and the score in physical activity in time 1 were both significant indicators of the factor "Sport and Physical Activity in Time 1", as indicated the maximum likelihood solution and measurement equations, reaching saturations over .60.

A structural equation model was tested with the total sample, which established a bidirectional relationship between "Life Satisfaction in Time 1" and "Sport and Physical Activity in Time 1", and unidirectional associations of both "Life Satisfaction in Time 1" and "Sport and Physical Activity in Time 1" with "Life Satisfaction in Time 2". The model presented good data fit, Satorra-Bentler χ2(48, N = 714) = 95.69, p < .001, χ2/df = 1.99, CFI = .983, SRMR = .030, RMSEA = .037, 90% CI RMSEA =.026 - .048. Life satisfaction after the one-year follow-up was explained in a 26.1% by initial life satisfaction and scores in sport and physical activity one year before. All measurement equations and construct equations were significant. "Life Satisfaction in Time 1" and "Sport and Physical Activity in Time 1" were positively associated, β = .15, p < .001, and "Life Satisfaction in Time 1", β = .48, p < .001, and "Sport and Physical Activity in Time 1", β = .12, p < .001, presented positive effect on "Life Satisfaction in Time 2". Then, this model was tested separately in girls and boys. Results indicated than only in girls, β = .14, p < .001, but not in boys, β = .05, p = .180, "Sport and Physical Activity in Time 1" presented a significant and positive effect on "Life Satisfaction in Time 2". In girls, model also reached good data fit, Satorra-Bentler χ2(48, N = 714) = 70.98, p = .017, χ2/df = 1.48, CFI = .985, SRMR = .037, RMSEA = .036, 90% CI RMSEA = .016 - .053, explaining up to 31.2% of "Life Satisfaction in Time 2". Both construct and measurement equations were also significant and standardised residuals were between -0.1 and 0.1. Figure 3 represents the structural equation model in girls, indicating standardised solutions.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The aim of this study was to determine the impact of the physical and sport activity on life satisfaction by gender after a one-year follow-up in a sample of southern Spain teenagers aged between 13 and 16 years. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the associations between sport and physical activity and life satisfaction from a longitudinal perspective in adolescence in Spain. The results from a structural equation model showed that the frequency of sport practice and physical activity in time 1 has a positive effect on life satisfaction at time 2, although this effect was only significant in girls, and not in boys' subsample. Our results indicated that girls who rarely or never play sports or physical exercise out school hours, showed a lower life satisfaction after a one-year follow-up than girls who participated in sports activities or made physical exercise several days a week. These gender differences are in line with several cross-sectional studies, such as those by Brooks et al. (2014) and Zullig and White (2011), who indicated a positive and significant relationship between the practice of vigorous physical activity in leisure time and life satisfaction only in the subsample of girls. Similarly, Valois et al. (2004) noted that the positive association between no participating in sports activities organised by the school and life dissatisfaction was significant in girls, but not in boys. However, other physical activities variables, i.e., "no exercise at least 20 minutes in the last week" or "no exercise to strengthen or tone the muscles" were related significantly in that study with life dissatisfaction only in boys. Furthermore, our conclusion regarding longitudinal association in adolescent girls between physical and sport activity and life satisfaction is also consistent with the longitudinal evidence provided by the HUNT study in Norway. Rangul et al. (2012) showed that girls who were physically active in adolescence and young adulthood reported greater life satisfaction than those who were inactive in adolescence (even if they were active in young adulthood). In the case of boys, the improvement due to physical activity in adolescence was observed in the reduced scores in depression, but not in life satisfaction.

Although, to our knowledge, no study has yet addressed the reasons for this relationship, several explanatory mechanisms could be proposed regarding the potential of physical and sport activity to improve life satisfaction in adolescents, especially among girls. Furthermore, it is not easy to provide an accurate explanation for this fact, since there are many psychological, social and family factors that can foster a positive life satisfaction in young people (Proctor, Linley, & Maltby, 2009). One of the possible explanations for this relationship may lie in the establishment of peer relationships through participation in sport activities (Laird, Fawkner, Kelly, McNamee, & Niven, 2016). Sport and physical activities per se do not ensure that adolescents can benefit from higher quality social relationships that result in an improvement in life satisfaction. Instead, participating in a group activity collects a series of conditions to strengthen social and emotional ties, such as sharing common goals, the establishment of cooperative relationships necessarily in order to achieve the success of the group and the experience of sharing positive and negative emotions associated with the success or failure of the group activity (Lopes, Gabbard, & Rodrigues, 2016). Sports clubs provide conditions for adolescents to pursue a healthy life-style and psychological adjustment, as well as influencing positively their future expectations toward happiness (Gísladóttir, Matthíasdóttir, & Kristjánsdóttir, 2013). In fact, previous studies have reported that the quality of friendships at this life stage has a significant effect on psychological well-being (Raboteg-Saric & Sakic, 2014), underlining even greater effect on girls than boys (Almquist et al., 2013). This gender difference could explain why the practice of physical and sport activity has a positive impact only on girls' life satisfaction.

The development of stronger peer relationships through sport participation and physical activity could also contribute to foster social support for coping with developmental challenges and tasks (Babiss & Gangwisch, 2009). Hankin, Mermelstein, and Roesch (2007) concluded that adolescent girls reported poorer psychological adjustment partly due to a greater presence of stressors related to events with peers. Social support has a direct positive effect on life satisfaction (Cikrikci & Odaci, 2016), and subjective well-being in adolescence (Suldo & Huebner, 2006), which could constitute another protective factor for adolescent life satisfaction. According to the study by Raboteg-Saric et al. (2014), the effect of the friends' support on subjective well-being during adolescence may be due to its influence on self-esteem. Some studies have concluded that adolescent girls present lower overall self-esteem than boys (Gomez-Baya, Mendoza, & Paino, 2016; Quatman & Watson, 2001). Daniels and Leaper (2006) observed that peers acceptance partially mediated the relationship between sports participation and global self-esteem in adolescence, in both girls and boys. Furthermore, Dishman et al., (2006) showed that physical self-concept and self-esteem mediated the relationships between physical and sport activity and depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. A recent study by Gomez-Baya, Mendoza, Gaspar de Matos, and Tomico (2017) have examined the moderation of gender in the mediation of body satisfaction between sport participation and depressive symptoms. In this cross-sectional study with Spanish adolescents, greater sport participation was directly associated with less depressive symptoms, and indirectly through an improvement in body satisfaction. Some gender differences were observed in this mediation, so that sport participation presented more positive effect on boys' body satisfaction, while body dissatisfaction was more related to depressive symptoms among girls.

Study limitations and future research lines

Despite the contributions of this study, some limitations should be acknowledged. First, although a longitudinal design allows examining relationships between antecedents and consequents, no causal relationships can be concluded. A study experimental design with variable manipulation is recommended as a future research line in order to explore causation. A randomized controlled trial is suggested to perform an experimental design. Second, the assessment was based on the individual application of a self-report instrument, which only provided subjective information. Another future research line could come from the evaluation of relevant others, such as peers and family (Laird et al., 2016; Yao & Rhodes, 2015). Third, another limitation is the high attrition after the follow-up. Participants who did not complete the second assessment were mostly boys and presented a greater mean age and lower initial scores in life satisfaction. Although results may be biased by this attrition, sample size was big enough to secure statistical power. Future research should take great care of reducing the rate of attrition. Fourth, a deep understanding of the relationships between physical and sport activity and life satisfaction could need the analysis of the mediation of other important variables, such as motives for practicing sport, personality traits or self-efficacy in sport activities. As well, other aspect of psychological well-being could be measured as a future research line, such as positive and negative affects. Finally, further examination of the mechanisms which explain the association between physical and sport activity and life satisfaction could be explored by conducting a qualitative data collection with focus groups or individual interviews.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

Our results provide evidence on the key role of physical and sport activity on girls' life satisfaction. During adolescence, life satisfaction acts as a protective factor against risky behaviours (smoking, alcohol or drug abuse) and mood disorders, such as depression or anxiety (Gilman & Huebner, 2003). Therefore, our conclusions underline the need to design interventions from Sport Psychology (Canton Chirivella, 2016) to promote an active lifestyle in order to strengthen adolescent mental health in girls. These interventions are justified taking into account the high prevalence of physical inactivity among adolescents in Western countries, especially in females. As well, adolescent girls present more internalizing problems than boys during this developmental transition, with consequences in adulthood (Lewinsohn et al., 1999). The results of our study also showed significant gender differences in both physical activity and sport participation, with adolescent girls reporting lower frequency than boys. Although some common protective factors have been described by literature in order to promote physical and sport activity (Marques et al., 2015; Navas & Soriano, 2016), they may present a differential effect by gender. Attitudes towards sexual diversity in sport have been recently examined by researchers (Piedra, 2016). A scoping review by Spencer, Rehman, and Kirk (2015) has highlighted some gaps in the literature in this regard and the need to examine how girls' physical activity is affected by gender norms and feminine ideals through influencing self-perceptions and body-centered discourse. Slater and Tiggerman (2010, 2011) have highlighted that body image concerns and lack of interest and self-efficacy would contribute to reduced rates of sport and physical activity in adolescent girls. In other study, Kantanista et al. (2015) have highlighted that a better body image is a stronger predictor of moderate-vigorous physical activity in boys than in girls. Thus, a meta-analysis by Babic et al. (2014) has concluded that gender moderates the link between physical self-concept and physical activity in youth, so that a lower physical self-concept in girls would explain their lower scores in physical activity.

Furthermore, Tereza Araujo and Dosil (2016) have recently found that a more positive attitude toward physical activity in men may explain the greater practice in this subsample, compared to women. Self-determination theory is a motivational approach to well-being that has been used to design physical activity programs (Mitchell, Gray, & Inchley, 2015). Compliance with physical activity recommendations among adolescents was related to positive perceptions of physical competence and autonomy, as well as to greater importance given to physical education (Murillo Pardo et al., 2015). A school-based physical activity programme developed by Mitchell et al. (2015) was found to be effective to improve the engagement of adolescent girls during physical education classes. This program conducted in Scotland and based on self-determination theory, showed that more supportive environment and a choice of activity resulted in increased participation and more positive perceptions in girls. Thus, motivational coaching interventions among girls could be recommended for active extracurricular activities (Colas Casaban, Exposito Boix, Peris Delcampo, & Canton Chirivella, 2017), especially those oriented to increase intrinsic motivation (Gutierrez, Tomas, & Calatayud, 2018). In Italy, other intervention based on self-determination theory (Girelli, Manganelli, Alivernini, & Lucidi, 2016) has addressed the promotion of physical activity jointly with the promotion of healthy eating with positive outcomes. A recent meta-analysis of the effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity among adolescent girls (Pearson, Braithwaite, & Biddle, 2015) has concluded that interventions should be guided by theory, performed in schools, be specific for girls, begin in an earlier life stage, use a multicomponent strategy and involve both the promotion of physical activity and the prevention of sedentary behaviour. Consequently, the design of intervention programmes aimed at promoting sport and physical activity should be gender-focused, and, in order to increase the efficacy of these interventions, girls' motivations, interests and needs should be considered.