Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Enfermería Global

versión On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.16 no.46 Murcia abr. 2017 Epub 01-Abr-2017

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.16.2.239881

Originales

Dietary habits of secondary school students in Andalusia during school time in relation to food stores in the environment

1Nursing Department. University of Huelva

2Clinical Management Unit Ciudad Jardín. Sanitary District Malaga.

3Clinical Management Unit Martos. Sanitary District Jaén-Sur.

4Clinical Management Unit Montequinto, Olivar de Quinto y El Campo de las Beatas. Sanitary Management Area South of Seville. Spain.

Background

The analysis of the environmental context is indispensable to study the eating habits in adolescents. Feeding practices during the school day the students user surrounding grocery stores of secondary schools in Andalusia and their characteristics are described.

Methods

Descriptive cross-sectional study of 8068 students and 95 secondary schools. Multistage cluster sampling: Stratified random sampling by province and population size and systematic for classrooms. The analysis of the type of store, food supply, distance and visualization from the school and students´ demands was conducted by direct observation and interviews. The socio-demographic characteristics and feeding practices were got through questionnaire.

Results

The schools are surrounded by shops in which the food supply is aimed at students (72, 63 %). Pubs and cafeterias (55), grocery stores and tuck shops predominate. The presence of sweets, processed baked goods and sandwiches is confirmed in all the stores. 25.73% of students buy their school meals in these shops. There are statistically significant relationships between the consumption of sweets and fried packaged packages and to go out the high school during the playground.

Conclusions

The number and characteristics of the stores surrounding the schools require studying its influence over students eating habits in order to establish public health measures to control the detected unhealthy supply.

Keywords Diet; Secondary Education; health promotion; food education; eating habits; teenager

INTRODUCTION

Growing concern about the link between eating habits and the health of young Spanish people matches findings in many studies of a dietary deficit in this life stage1)(2. The infant and adolescent population is healthy by definition, however, certain maladjusted lifestyles are giving rise to serious health problems. School students’ diet is under threat from a growing number of variables in the form of a wide range of readily available food products that are not suitable for a healthy diet3. Various studies suggest that the problems derived from teenagers’ and young people’s eating habits in Europe follow a similar pattern, after accounting for geographical and socio-economic inequalities, group and community4.

Socialization in young students occurs at school and so develops there during a large part of their day. So, any analysis of the factors that influence their dietary practices must include the study of the food on offer to students in the environment closest to them5. Understanding the influence of location is a big challenge for health researchers, and indeed the growing prevalence of obesity worldwide has certainly focused minds on the factors related to setting6)(7)(8)(9. Studies that analyse the environmental context re increasingly useful, such as those that investigate the characteristics of a neighbourhood in order to better direct interventions that might prevent obesity and promote healthy habits among the local population5. The conditions of access to food at school, at home and food-selling establishments are features of the setting that must be taken into account when fixing health policy priorities10.

There are numerous studies both in the USA8),(11),(12 and Australia8 on the relation of students’ food consumption to the availability of food at external outlets. This approach is still nascent in Europe, however the IDEFICS13 study is a significant contribution for its monitoring of the environmental risks associated to overweight in infancy, even though it could not demonstrate that retail outlets situated near schools were responsible for greater food consumption among young boys and girls. However, studies in the USA have established some positive links14.

The approach of these authors shows the importance of studying the typologies of these peripheral establishments and the reasons behind their location around educational centres. The availability of such premises can be considered a meso-level factor to be analysed in order to determine which types of urban environments most benefit the development of obesity5.

Besides easy access to healthy food, other defining features of a neighbourhood to be considered are the quality of the physical environment, the socio-economic level of the area and health inequalities. Studies in the USA have shown that access to shops which sell healthy food is more difficult in low-income areas5. In line with this approach, studies that investigate the influence of the area surrounding a school on students’ eating habits are increasingly relevant15.

In Spain, it is difficult to gauge the range of food available and the extent of its consumption by students at shops near secondary schools since this subject has so far aroused little or no interest in the authorities in this country. Although in recent years some legal measures have been passed to control the products consumed and/or purchased at schools, with Law 17/2011 on Food Safety and Nutrition16, its implementation and development in secondary schools in Andalusia has been patchy to say the least17. Given the lack of research on this subject in our region, this study aims to describe and classify the commercial establishments situated near secondary schools whose products include food aimed at student consumption, to characterize the student who uses such shops and identify possible influences on their eating habits. This article is part of a broader study carried out in Andalusia called the ANDALIES project.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

In 2011-2012 we carried out a descriptive observational study of commercial food establishments on the periphery of the school zone; we sampled 95 secondary schools (IES) and 8,068 students in the eight provinces of Andalusia. The educational centres were selected by random proportional stratified sampling for province and size of habitat, with a sampling error margin of (10% and confidence level of 95.5%. The students were chosen by systematic sampling of classes in the secondary schools selected. The margin of sampling error was + 2% with a confidence level of 95.5%. The variables for the food establishments studied were: type of establishment, type of food on offer, distance from the school, visibility of the outlet from the school and student demand. The data were gathered by direct observation of the shops by means of an observation guide piloted at two educational centres in the province of Huelva in 2010 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Observation guide: Study of external commercial establishments for the supply of food during school hours on the periphery of the school zone

To triangulate the information, we also took photos and videos, and we interviewed shop owners on the type of products most in demand by students, as well as head teachers on their knowledge of the shops around their schools whose products were aimed at student consumption.

The student variables were: gender, age, province, population size, school café, breakfasting at home before school, type of breakfast, type of snack consumed in school break time, consumption of sweets and/or cakes during the school day, consumption of crisps and sweets, physical exercise taken outside school, visits to food shops outside the school during break time, and the type of establishments frequented. The processing and analysis of the information was done in two ways: the quantitative data were organized and processed by the SPSS v.18 software package, and the median, standard deviation, the relative frequencies and the chi-square were calculated for the relational analysis; the qualitative analysis of the information obtained from the observation guides, images and interviews was set out in the form of classification tables to produce a documentary analysis.

RESULTS

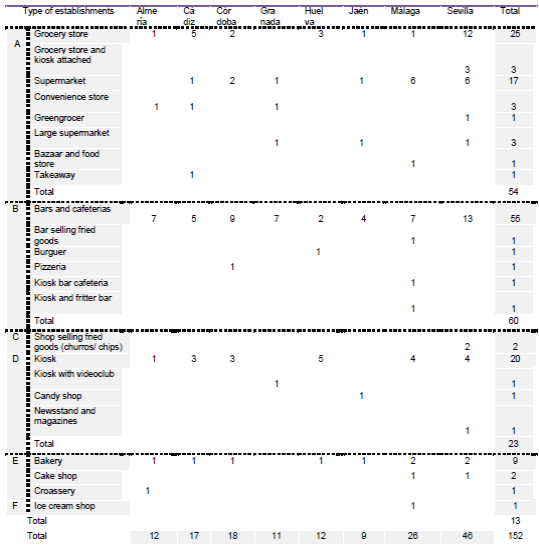

We found that 72.63% of the secondary schools studied in Andalusia have establishments nearby that can sell food products to students. Huelva is the province with most food stores close to the school building, Jaen and Granada the fewest (Table I). The total number of establishments was 152, distributed according to province in Table I.

Table I Distribution of commercial establishments and distance in paces to the secondary schools in the province

The range of shops is broad (24 types) so we classified them in six sections to simplify the analysis of the kind of food they sell (Table II).

Section 1 consists of 54 shops which include establishments whose main feature is the sale of food products. This group is highly diverse in terms of size and range of products on offer, with 42.1% displaying a big selection of sweets and pastries, and cold meat sandwiches and soft drinks.

Section 2 represents the most common type of establishment in Andalusia. We registered 55 bars and cafés around the schools sampled, rising to 60 if we include similar establishments. Although some of these businesses sell cakes and pastries, and sweets and sandwiches, the main product on offer is the typical Spanish breakfast of white coffee, toast with butter and pâté, sometimes with fruit juice.

Sector 3 establishments sell the traditional fritters and chips.

Section 4 is made up of sweet shops, which numbered 23 kiosks, 20 of which were exclusively traditional sweet sellers while the remainder sold sweets overlapping with other products. Huelva is the province with most sweet shops near educational centres, with 71.42% of them located close to its secondary schools.

Sector 5 includes bakeries whose traditional style has changed with the installation of ovens to produce pre-baked hot bread. All such establishments sell pastries, sandwiches and sweets.

The measurement of the distance between the secondary schools in the sample and the food retail outlets nearby (Table I) showed that the closest was a mere 10 paces away, in Huelva and Córdoba, with the average distance between school and shop being 27.25 paces across Andalusia. Córdoba and Cádiz are the provinces with the highest percentage of establishments closest to school (50% and 41.17%, respectively), while in Jáen and Málaga such shops are furthest, at more than 150 paces, from most of the schools in those provinces (77.77% and 61.53%, respectively).

Although 65.79% of shops are not visible from the schools sampled, they are frequented by students, and sometimes even by teachers, according to the shop owners and head teachers interviewed.

The interviews with the teaching staff revealed that 73.68% of them are aware of the existence of the shops close to the schools where food products are on sale, and that students visit them before or during break time, in the case of those aged 18 or older who have permission to leave the centre at those times. Some responses revealed teachers’ knowledge of the type of products on sale, such as sandwiches, sweets and drinks: “the students buy lots of sweets but outside school time” (P5C77); “Before coming to school, they stop at a shop nearby to buy sweets” (P7C72); “There’s a bakery that sells cold meat sandwiches” (P6C47). Only 12.63% of the head teachers surveyed were unaware of the presence of this type of shops near their schools.

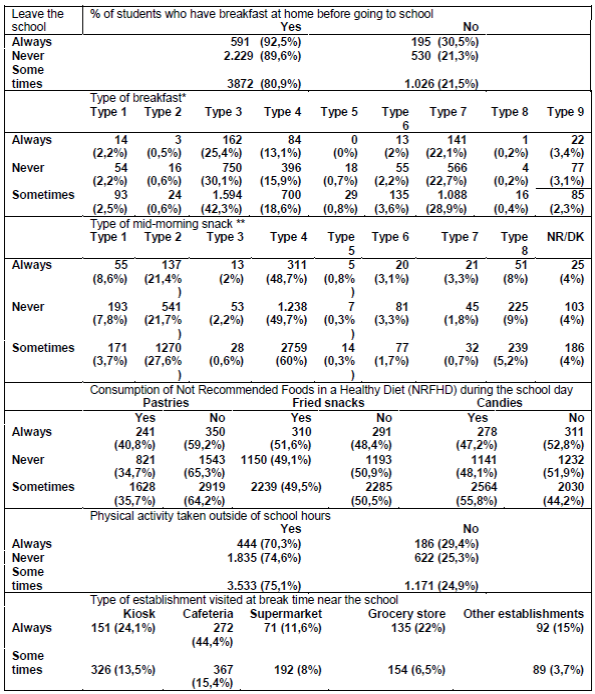

In total, 25.73% of secondary school students buy their mid-morning snack in a shop nearby; around 8% go out of school at break time and 31% remain behind, with 60.5% stating that they go out occasionally to buy something at a food retailer’s.

The socio-demographic characteristics and the eating patterns of those students who state that they go out of school or stay behind are described in Tables III and IV. The data show that the type of establishment most used by students is the bar and café (34.55%), followed by the kiosk (25.79%), the food store (15.63%), supermarkets (14.22%) or others (9.78%).

Table IV Food characteristics, practice of physical activity and type of establishment visited by students at break time

The provinces where students go out of school most during break time are Almería (32.6%) and Huelva (20.2%), while students in Sevilla tend to go out more sporadically (29.8% responded that they sometimes go out). This habit is more frequent in secondary schools in cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants (38.2% and 28.2%). They tend to go out even though there is a café in 75.7% of the centres surveyed.

We found that 30.5% of the students skip breakfast at home before arriving at school. In the cases where students have breakfast it is light, consisting of a half piece of toast and/or cereals (25.4%), or just liquid (22.1%). At break time, 48.7% consume the typical secondary school break time snack in Andalusia of a sandwich and a mini-fruit juice from a carton; 21.4% consume a liquid with a product not recommended for a healthy diet; 8.6% only liquids, and 8.4% add a product unsuitable for a healthy diet to another product they consume at break time, meaning that 38.4% of secondary school students consume products that are considered inappropriate for healthy eating.

The relational analysis reveals significant relations between the variable Go out of school during break time to buy food and variables such as province, population size, availability of a café on the school premises, type of breakfast, type of break time food consumed and consumption of sweets (Table V).

Table V Value of the relational statistic between leaving the school during recess and several socio-demographic variables and eating habits of the students.

Students in Almería and Huelva go out at break time significantly more than those in the other provinces in Andalusia; and this occurs more often at schools in cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants. Students go out of school more often from centres that lack a cafeteria. In terms of eating habits, it is significant that the students who go out at break time consume one of two types of breakfast: half a toast or cereals with milk (41.8%), or a liquid only (29.2%).

It is noteworthy that 81% of the students who acknowledge consuming a breakfast of low nutritional value go out of school at break time to buy food. The mid-morning snack is most likely to consist of a solid (sandwich) and a liquid (a commercialized fruit juice), which is the case in 58.9% of students who leave school at break time, a sandwich and fruit juice constituting the typical Andalusian secondary school student snack.

Students who go out at break time also consume more sweets (71.4%) than those who stay at school (65.5%), and the sporadic consumption of sweets and cakes is greater among students who visit these establishments during break time (76.5%). We also found that those students who stay on the school premises at break time consume more sweets and/or pastries and packets of crisps (14.1% and 25%) than those who actually go out (5.5% and 5.8%), which shows that the location of food outlets nearby is not a greater influence on the students than the food on offer at the school shop or café.

DISCUSSION

The data show that there is a large number of secondary schools in Andalusia that have retail food outlets nearby which sell products of low nutritional value and which are open throughout the school day. Such establishments are frequented by some 25% of the students during their break time, some on a constant basis and the majority sporadically. This finding fits with those of other authors who have also researched the elements in the environment that boost the consumption of food that is high in calories and low in nutritional quality. One US study identified four types of food retail outlets close to schools12: supermarket chains, independent supermarkets, convenience stores and other comestible outlets. Its conclusion was that shops with bigger selling space offer fresh food products of greater nutritional value than other types of establishments. In contrast, other studies show that convenience stores located within a 10-minute radius of the school -which in our study correspond to small food outlets open all day- are associated to a higher rate of overweight students, compared to students attending schools that do not have such establishments nearby11. Our research shows that the type of food outlet most frequented by the students in our survey was the bar and café, hardly surprising since such establishments are the most common location for snacking in the eight provinces of Andalusia. Our research also found a large number of shops near schools that sell food products that are deemed unhealthy and which are aimed directly at students, and most alarmingly, kiosks that sell nothing but sweets. The province of Huelva registers the highest number of such establishments near its secondary schools, while Jaén and Granada have the fewest. This explains why Huelva students are among the most numerous in leaving school at break time. Although our study has not examined the relation of this factor to the rate of obesity, we can conclude that the prominence of small shops and kiosks, whose scope for offering products that are not recommended for a healthy diet is considerable, amounts to a serious risk to the healthy eating habits of secondary school students in Andalusia who study within an educational environment that is indeed far from healthy. The availability of sweets for sale is evident across all types of food establishments, although less so in Sector 2 (bars and cafés) and Sector 3 (traditional fritters and chips). And this situation is aggravated by a lack of control or policy to promote healthy eating habits by the central or local authorities. The widespread availability of confectionary seems to influence the greater consumption of sweets among students who go out at break time, whereas, the consumption of cakes and packets of crisps is less among those who go out, perhaps due to the availability of such products in school shops19 which means students do not have to go out to buy them.

Regarding other eating habits among secondary school students in Andalusia, we found that those who go out at break time also have poorer breakfast-eating habits than those who stay in, although this could be related to other social factors that condition teenagers’ behaviour. The easy accessibility of these establishments for students in their everyday school lives is clearly a factor that can influence unhealthy food choices, and which competes with the traditional family diet.

Another of the findings in our study regarding the quality of the food on offer to students is one related to the disappearance of traditional, nutritional bakery-baked bread from the sandwiches on sale to students. The market penetration of pre-baked bread heated up on site across all consumer sectors is now widespread, and it is a feature of the food available to students during their school day18.

The methods used to measure the distance between school centres and food retail outlets are varied. Some studies measure distance by the time needed to reach such establishments11, but we have found none that have measured the distance in terms of the number of paces needed to walk from the secondary school to the shop. In Andalusia, most of the shops are at a short distance from the school, although distances vary among provinces. Cádiz and Córdoba have the highest number of shops that can be considered close by, whereas in Jaén and Málaga the outlets are further afield. Huelva tops the list in terms of food establishments and their closeness to schools, so the school environment in this province is at greatest risk in terms of the availability of food products for students that are not recommended for a healthy diet. This could be associated to a study that shows that Huelva students are the biggest consumers of these products in the region1.

Although head teachers are aware of the presence and influence of these establishments, it is not seen as an issue of great concern since as soon as students walk off the school premises they are no longer the responsibility of the teaching staff.

It is clear that any environmental intervention that aims to effectively combat the pandemic of obesity must assist and support students’ dietary decisions6. Any strategy aimed at the authorities must find ways to foment the consumption of fruit among students by promoting access to these products both inside and outside school.

Future lines of research could be studies that analyse students’ eating habits outside the home, especially those practices and food choices linked to the student environment outside school; we need more studies on the features of the students’ settings in order to determine which environmental factors affect them, which ones can have a negative influence and which can benefit healthy eating habits. It would also be interesting to analyse not just student food consumption outside school during break time but also what they buy in these shops on the way to school first thing in the morning. This study has not considered, and without doubt it might well have increased, the frequency of use of these establishments.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to the Confederation of Parents Associations of Andalusia for Public Education (CODAPA) for raising the petition to carry out this study and the support they have given us throughout its development

REFERENCES

1. García Padilla FM, González Rodríguez A, Martos Cerezuela I, González Delgado A. Perfil alimentario del alumnado de secundaria en Andalucía durante la jornada escolar. Nutr clín diet hosp. 2013; 33: 129 [ Links ]

2. Palenzuela Paniagua SM, Pérez Milena A, Pérula de Torres LA, Fernández García JA, Maldonado Alconada J. La alimentación en el adolescente. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2014; 37: 47-58 [ Links ]

3. Francis LA, Lee Y, Birch LL. Parental weight status and girls´ television Beijing, snacking, and body mass indexes. Obes Res clin Pract. 2003;11: 143. Disponible en: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2530922/ [ Links ]

4. Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in adolescente. Disponible en: http://www.helenastudy.com [ Links ]

5. Black J, Macinko J. Neighborhoods and obesity. Nutr Rev. 2007; 66: 2-20. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.00001.x [ Links ]

6. Lake A y Townshend T. Obesogenic environments: exploring the built and food environments. JRSH. 2006; 126: 262.Disponible en: http://rsh.sagepub.com/content/126/6/262 [ Links ]

7. Feng J, Glass TA, Curriero FC, Stewart WF, Shwartz BS. The built environment and obesity: A systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence. Health Place. 2010; 16: 175 [ Links ]

8. Fleischhacker SE, Evenson KR, Rodríguez DA, Ammerman AS. A systematic review of fast food access studies. Obes Rev. 2010; 12: 460. Doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00715.x [ Links ]

9. Richardson AS, Boone-Heinonen J, Popkin BM, Gordon-Lansen P. Neighborhood fast food restaurants and fast food consumption: A national study. BMC Public Health. 2011; 11:543. Disponible en: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/11/543 [ Links ]

10. Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O´Brien R, Glanz K. Eating Environments: Policy and Environmental Approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008; 29: 253 [ Links ]

11. Howard PH, Fitzpatrick M, Fulfrost B. Proximity of food retailers to schools and rates of overweight ninth grade students: an ecological study in California. BMC Public Health. 2011; 11:68. Disponible en: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/11/68 [ Links ]

12. Powell LM, Auld MC, Chaloupka FJ, O´Malley PM, Johnston LD. Associations Between Access to Food Stores and Adolescent Body Mass Index. Am J Prev Med. 2007; 33: 301 [ Links ]

13. Ahrens W, Bammann K, Siani A, Buchecker K, De Henauw S, Iacoviello L, et al The IDEFICS cohort: design, characteristics and participation in the baseline survey. Int J Obes. 2011; 35: S3-S15. [ Links ]

14. Buck C, Börnhorst C, Pohlabeln H, Huybrechts I, Pala V, Reisch L, et al. Clustering of unhealthy food around German schools and its influence on dietary behavior in school children: a pilot study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013; 10:65. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-10-65 [ Links ]

15. Engler-Stringer R, Le H, Gerrard A, Muhajarin N. The community and consumer food environment and children's diet: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014; 14:522. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-522 [ Links ]

16. Boletín Oficial del Estado. Ley 17/2011, de 5 de julio, de seguridad alimentaria y nutrición. BOE núm 160 de 6/7/2011. [ Links ]

17. González Rodríguez A, García Padilla FMª, Liébana Fernández JL, Delgado-de-Mendoza-Núñez J, González-de-Haro MD, Silvano-Arranz A, et al. La ley de Seguridad alimentaria y nutrición en los centros de educación secundaria andaluces. Gac Sanit. 2013; 27: 357 [ Links ]

18. Gil A, Serra L. Libro blanco del pan. Madrid: Médica Panamericana; 2010. [ Links ]

19. González Rodríguez A, García Padilla FMª, Martos Cerezuela I, Silvano Arranz A, Fernández Lao I, et. al. PROYECTO ANDALIES: Consumo, oferta y promoción de la alimentación saludable en los centros de educación secundaria de Andalucía. Nutr Hosp. 2015; 31(4): 1853-1862 [ Links ]

Received: October 18, 2015; Accepted: December 18, 2015

texto en

texto en