Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Enfermería Global

versión On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.20 no.62 Murcia abr. 2021 Epub 18-Mayo-2021

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.429701

Originals

Strategies for increase satisfaction with nursing care in hospitalized children: a Delphi study

1Egas Moniz Interdisciplinary Research Center (CiiEM), Egas Moniz School of Health, University Campus, Caparica, Portugal,

2Portuguese Catholic University, Institute of Health Sciences, Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Health (CIIS), Palma de Cima, 1649-023 Lisbon, Portugal

Introduction:

Satisfaction with nursing care in the area of hospitalized children is poorly studied. The investigation has been focused on satisfaction predictors and components therefore it is essential to identify strategies that promote satisfaction.

Materials and method:

A cross-sectional, observational and exploratory-descriptive study was carried out. It aims to identify the strategies described by nurses that contribute to increasing the satisfaction of school aged children and their parents with hospitalization. The delphi panel was used as a data collection technique and, as data analysis techniques, content analysis (in round 1) and descriptive statistics (round 2) were used. The study was applied between November 2018 and February 2019 to a sample of 90 nurses from 6 health institutions, after obtaining a positive feedback from the respective ethics commissions.

Results:

A response rate of 52% (n = 47) was obtained in round 1 and 47% (n = 42) in round 2. In round 1, 13 strategies were identified in relation to children, which reached consensus in round 2, being mainly directed to the transmission of information, family involvement, play and pain relief. Regarding parents, 12 strategies were identified by consensus in round 2.

Discussion:

Family involvement and the transmission of information are areas of intervention that have been identified in both groups.

Conclusion:

It was possible to determine nursing interventions that could promote an increase in the satisfaction of children and parents, focused primarily on information and family support and involvement.

Key words: child; hospitalization; nursing

INTRODUCTION

Customer satisfaction is understood as a relevant indicator of the quality of care and has been the focus of numerous research studies worldwide (1. It is defined as the degree of congruence between the expected care and the care actually received, being consensual among all health professionals that nurses are the group that most contributes to customer satisfaction in the context of hospitalization2. Studies have focused on both the identification of the attributes that characterize satisfaction and its relationship with sociodemographic data3.

In the scope of pediatric care, satisfaction is usually measured using close adults such as parents or teachers, and the child's voice is excluded4. In fact, parental satisfaction has been used to measure the quality of pediatric health care and is closely linked to the adequacy of the child's treatment and the performance of nursing professionals5. However, there is a more integrative approach to assessing satisfaction with nursing care during hospitalization that includes the perspective of all stakeholders: children, parents and nurses6.

Therefore, this study is part of a broader investigation project that focused on customer satisfaction. It aimed at improving the quality of care by contributing with a set of guidelines for the practice of care.

In a first stage, satisfaction with nursing care was evaluated, having school children and parents as subjects7,8 and in the second stage, data was collected from nurses. In this article, data regarding the second stage of this project will be presented.

We aim to identify the strategies described by nurses that contribute to increase the satisfaction of the school-age child and his parents with hospitalization.

We aimed at the perspectives of nursing professionals as privileged actors collecting their contributions on this topic. Thus, we intend to answer the following research question: what are the strategies described by nurses that contribute to increase the satisfaction of schoolchildren and their parents with hospitalization?

MATERIAL AND METHOD

The study is cross-sectional, observational and exploratory-descriptive type.

In the first stage, satisfaction questionnaires were applied to school children and parents. Regarding children, the Child Care Quality at Hospital questionnaire9, after translation and cultural validation10, was applied to a sample of 252 children between 7 and 11 years old. Regarding parents, the Citizens Satisfaction Scale for Nursing Care11 was applied, after adapting the instrument, to a sample of 251 parents. In the second stage, nurses were considered as subjects.

Thus, the delphi panel was applied as an investigation technique that uses a group of participants, also called experts12. In nursing, the expert is understood as the professional with skills, abilities and knowledge, acquired through education and professional experience13. The delphi panel uses a series of inter questionnaires related to controlled feedback and is particularly useful in identifying strategies and interventions that can be used within the scope of care practice14. Its main advantage is the breadth of the study without geographical limits for the selection of experts, requiring no face-to-face meeting15. In the present study we opted for this technique since the study was carried out with experts from 6 different hospital institutions.

Data collection and sample

Data collection was performed electronically using Google Documents( form creation tool. As for the experts, their selection usually results from specific criteria that derive from the objective of the study12. Data collection took place in 6 hospital units in the Lisbon and Vale of Tejo region, in 9 pediatric inpatient services. For sample selection, the following inclusion criteria were established: nurses belonging to the nursing teams, where the study was applied in the first stage of the investigation and with professional experience in the field of pediatrics ≥ three years in order to ensure sufficient knowledge about the subject. The number of experts to be used is not consensual and, in fact, the validity and confidence of the technique do not increase significantly with> 30 experts12. Associated with the sample size, it is crucial to attend to the percentage of abstention in this technique as the rounds go16. An intentional non-probabilistic sample was selected, composed of all nurses meeting the inclusion criteria, from the teams where the study was applied. 90 nurses were identified and invitations were sent to those who agreed to be contacted electronically.

Análise dos dados

In this study, two rounds were carried out. The number of rounds to be carried out depends on the nature of the investigation and the first round works as a brainstorming where open questions must be asked in order to generate ideas12. The following questions were constituted: which strategies promote the satisfaction of school-aged children (7-11 years) hospitalized with nursing care ?; what are the difficulties / constraints that you encounter in the operationalization of the strategies listed in your daily care practice ?; what strategies promote the satisfaction of parents of school-age children hospitalized with nursing care? and what are the difficulties / constraints that you encounter in the operationalization of the strategies listed in your daily care practice? In the first round, demographic data were integrated to allow sample characterization, namely: gender, age, academic qualifications and professional experience in child health (years). These data were processed using descriptive statistics through the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, version 24.

Regarding the open questions, they were analyzed using content analysis method, of thematic and frequency type, as suggested in literature12. This method is defined as a set of techniques for analyzing communications using systematic and objective procedures in describing the content of messages17. Thus, the responses of each participant were transcribed and each response was assigned a set of 2 letters and 2 numbers. The letter R (response) was followed by a number from 1 to 4 (1 - first question, 2 - second question etc.) and the letter P (participant) followed by a numeric character according to the order of response. The answers were transcribed and, following the steps of this technique, the material was pre-explored with a floating verbatim reading in order to organize, make operational and systematize initial ideas18.

In the material exploration phase, coding operations were performed and units of analysis were selected as content segments for categorization and frequency counting17. In the last step, which corresponds to the categorization and sub-categorization process18, classification units were grouped and classified according to a semantic criterion17. The categories were not initially defined as they emerged from the context of the participants' responses18.

The construction of the instrument that served as base for round 2 aligned the strategies and difficulties / constraints found in the first round. At this stage, it is intended to find consensus on the items that resulted from round 1 by the degree of agreement. We used again the form creation tool, Google Documents(, assuming the instrument used in this round, the same layout as well as the same organization used in the previous round in order to facilitate responses. In introduction, the invitation to participate in the second round was included and the main aspects of the study and its context were briefly recalled. It was explained what was required from nurses and the aspects associated with the technique were also recalled, namely the anonymity of the responses.

In this step, 4 questions were constructed containing the lists of strategies and difficulties / constraints obtained in the previous step. A 5-point likert agreement scale was associated with each item (1 - strongly disagree; 2 - disagree; 3 - neither disagree nor agree; 4 - agree; 5 - strongly agree). Additionally, in each aspect indicated, a field was made available for participants to fill in if they wanted to suggest any aspect not identified in the previous round and, therefore, not covered.

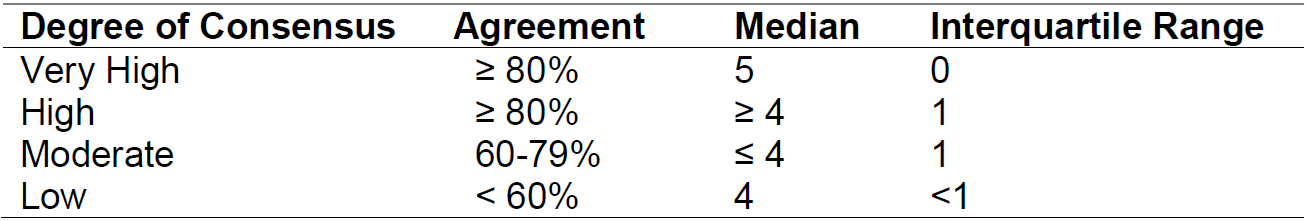

The return rate decreases during the rounds, which is identified in literature as one of the main difficulties in this technique12. To determine the degree of consensus, the degree of agreement, the median and the interquartile range were used as a resource, as explained in Table 1.

Only very high or high degree of consensus was considered, and those with a moderate or low degree of consensus were rejected. Regarding the degree of agreement, the sum of the responses “agree” and “strongly agree” was established as a criterion, followed by the median value and the interquartile range.

Ethical considerations

Study application was preceded by formal authorization procedures of boards of directors and ethical commissions of the different hospital units. At the same time, the national data protection commission approval was obtained (Approval n. 1644/2015). The selection of health institutions was intentional and it was intended to obtain the contribution of nurses where the study was applied in the first stage. Contact was made with the head nurses of each unit and professional email address of those nurses who met the inclusion criteria was requested. Head nurses asked each nurse for authorization to provide electronic contact and, to those who agreed to be contacted through this channel, an invitation to participate in the study was sent. An email was sent to each nurse requesting the collaboration in the study, clarifying what we intended with their participation and highlighting its importance. Nurses were invited to follow a link where they were presented with a text that: invited them to participate; explained the study; ensured voluntary participation without personal or professional damage; ensured confidentiality; explained the purpose of the study, its stages and objectives; clarified the methodology and what was intended of the participants with contact details of the main researcher. Participants then had to signal their acceptance to participate in the study and accept the use of email for future contacts in order to participate in the study. This way, we ensured voluntary participation, safeguarding the right to refuse at any time, making it explicit that there was no harm to the participants.

RESULTS

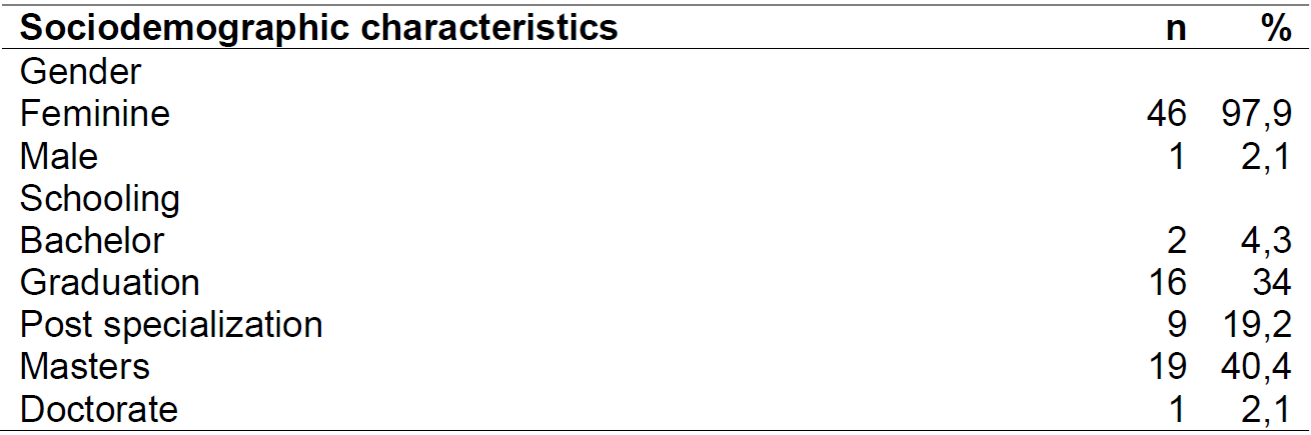

Regarding round 1, the invitation to participate in the study was sent simultaneously to all nurses and the first round was held during November 2018. Invitations were sent to 90 nurses and, after a reminder was sent, 47 responses were obtained, which corresponds to a return rate of 52%, which is within the rates identified in literature12. With regard to sociodemographic data, in the first round the participants age, ranged between 25 and 60 years with an average of 38.5 years and a professional experience in child health between 3 and 38 years, with an average of 14.7 years (SD = 7.7). The remaining characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

In the first round of the delphi panel, we asked nurses to indicate strategies that promote satisfaction both in children and parents, but also the difficulties / constraints to the implementation of these strategies. We intend to investigate interventions that could be used in care practice. A nursing intervention is “(…) any treatment that, based on judgment and clinical knowledge, a nurse puts into practice to enhance the client's results. Nursing interventions include both direct and indirect assistance; assistance aimed at individuals, families and the community; the assistance provided in treatments initiated by the nurse, doctor and another provider ”19. To deal with the increasing complexity of nursing care, systems of standardized languages should be used as instruments. In this sense, the Nursing Intervention Classification (NIC) is a standardized taxonomy of interventions provided by nurses, organized in a coherent structure, creating a standardized language that allows communication with clients, family and other health professionals19. On the other hand, when using the NIC language to document nurses' work in practice, it is possible to determine the impact of the results.

Thus, in the analysis of the answers given by the nurses, in this first round, we tried to integrate the NIC taxonomy, investigating interventions that could be used in the care practice.

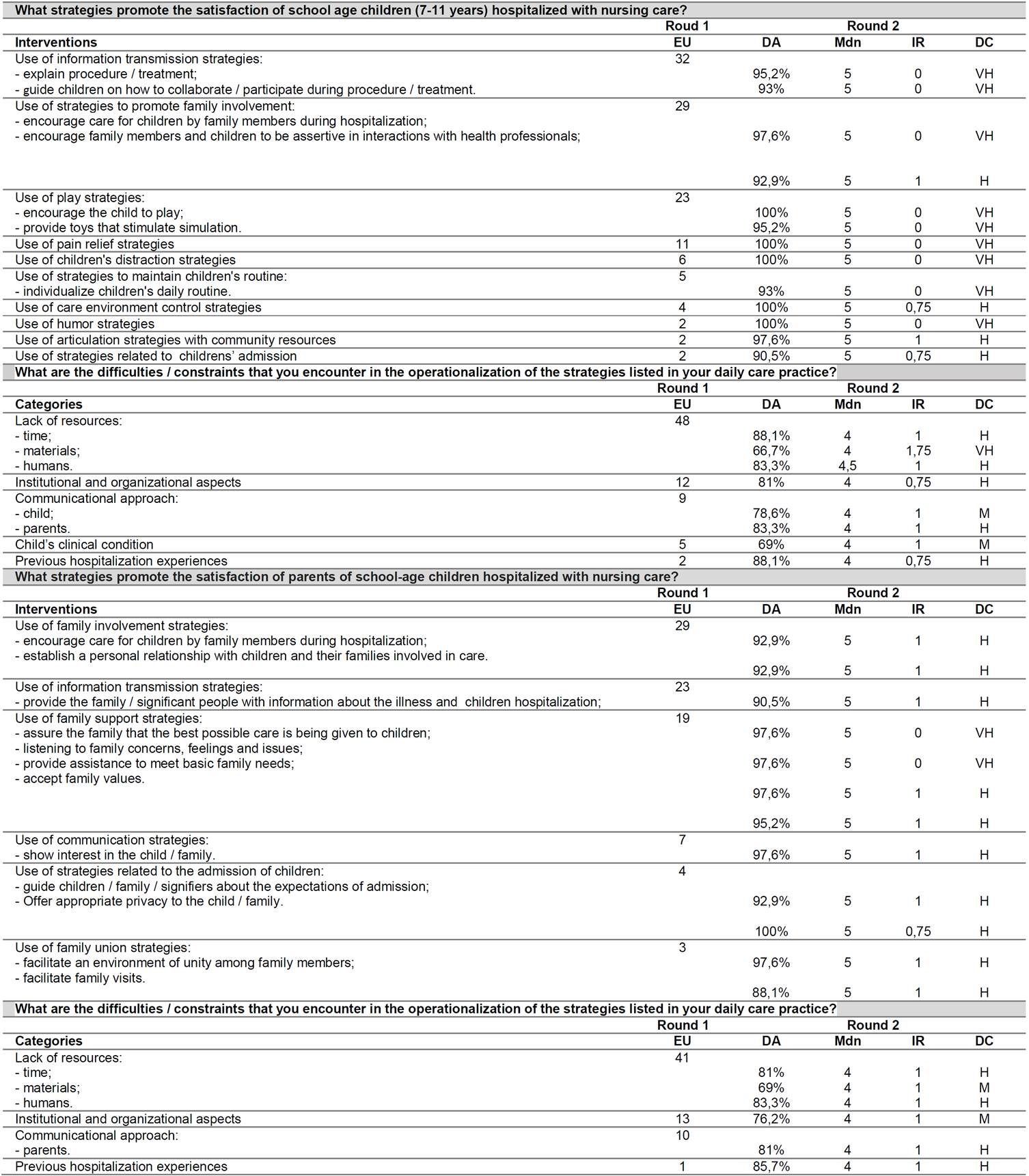

From the assessment of the responses of the first round to the four questions asked, the categories identified are summarized in Table 4. It should be noted that the total number of items to be moved to the second round must be verified as it may affect the response rate12.

After the content analysis of the responses of the first round was concluded, a total of 25 interventions were identified and we considered the number of items with an adequate dimension.

In round 2, it was intended to present the results of the first round and to understand which strategies were considered relevant by the participants. The second round took place during February 2019.

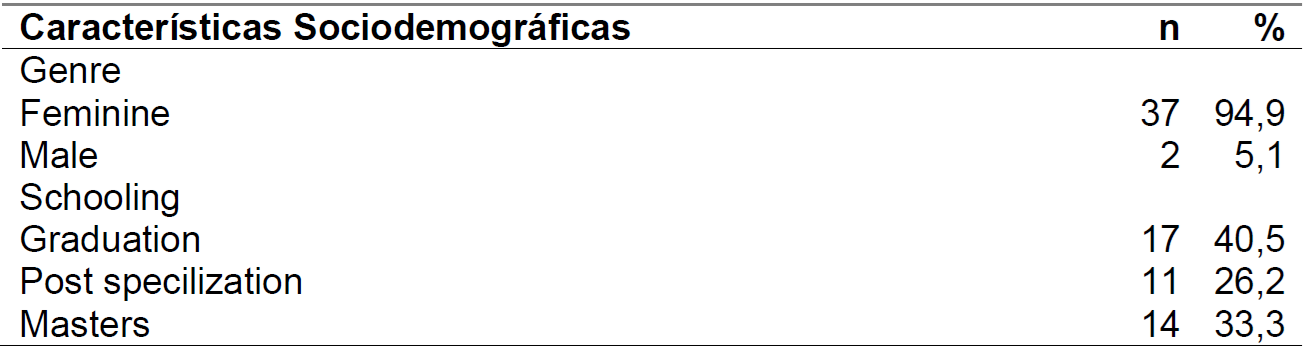

In the second round, invitations were sent electronically to the same 90 participants of the 1st round and a 47% return rate was obtained (n = 42). The age of the participants varied between 26 and 61 years with an average of 40.1 years (SD = 8.5) and a professional experience between 6 and 38 years with an average of 16 years (SD = 8.2) . Regarding qualifications, it appears that the majority of nurses had graduation as shown in Table 3.

Nurses' responses were analyzed and previously established criteria were applied. The results are summarized in Table 4.

DISCUSSION

In this study, nurses identified 13 strategies to increase satisfaction with nursing care of school-aged children. In the second round of the delphi panel, all strategies identified reached consensus among the participants. Regarding the transmission of information, it was the most mentioned by nurses (f = 32) in round 1. Two activities were identified: “explaining treatment / procedure” (f = 18) and “guiding the children on how to collaborate / participate during the procedure / treatment”(f = 14). Satisfaction and information are related concepts because children expect detailed information, appropriate to their stage of development, about the procedures before they are carried out and why they are carrying them out. Parents also stress the importance of communication between nurses and children. They expect nurses to be able to communicate effectively with children, even if the issues are not related to the hospitalization process20.

The second most mentioned intervention was “family involvement” (f = 29, round 1). Two interventions were identified: "encouraging the care of children by family members during hospitalization" (f = 22) and "encouraging family members and children to be assertive in interactions with health professionals" (f = 7). The first obtained a very high consensus and the second obtained a high consensus. Family involvement in care is identified as a relevant and central aspect in satisfaction with care during hospitalization. Children even see hospitalization as an opportunity to spend more time with their parents. Parents, on the other hand, articulate their involvement in care with their adequacy and a positive relationship with nurses21. Parental involvement in care is an integral part of child health care and integrates the dominant and widely accepted care philosophy as the most appropriate in pediatrics22.

The third major area of identified strategies was the “therapeutic toy” (f = 23) with reference to two activities: “encouraging the child to play” (f = 21) and “providing toys that stimulate simulation” (f = 7). In the context of children's hospitalization, playing can be used to promote health and well-being, promote comfort and educate children23. The importance of playing in the context of child hospitalization is irrefuTable and widely referred to in the thematic literature, emphasized by children, parents and nurses24. Among nurses, the use of therapeutic toys must integrate nursing care as it contributes to more systematic and specialized care25.

"Pain control" was identified as a strategy by nurses (f = 11) and is also a recurring theme. In children, adequate pain management appears as an expectation26 but also as a source of satisfaction9. However, it is as a source of dissatisfaction and bad experience that it appears more often identified among children25. With regard to parents, it is also a valued aspect27 and, among nurses, in this sample, this strategy achieved a very high consensus with a 100% level of agreement, which reflects the importance of the theme.

With regard to “distraction” strategies, they were identified with a frequency of 6. In the literature, play, distraction and entertainment appear as associated terms. Children expect nurses to be able to distract them during procedures and identify the use of toys and distraction as positive aspects of care25.

Interventions less frequently identified include “control of the environment” (f = 4), the use of “humor” (f = 2), “articulation with community resources” (f = 2) and “care with admission of children ”(f = 2). These are aspects less mentioned in literature, however still important.

Regarding difficulties and constraints, 8 items were identified in the first round and, in a way, reflect the strategies mentioned by nurses. The lack of resources (f = 48) was identified, which was subcategorized in time resources (f = 20), material resources (f = 12) and human resources (f = 16). In round 2, it appears that the items “lack of time resources” and “lack of human resources”, obtained a high consensus, while the item of material resources obtained a moderate consensus and was therefore rejected.

The issue of lacking resources is addressed in literature as an aspect that limits care and, therefore, generates dissatisfaction. Other constraints identified by nurses, in round 1, include the “institutional and organizational aspects” (f = 12), the “communicational approach” (f = 9) that are subdivided into “approach to parents” (f = 5) and “approach to children”(f = 5), “child's clinical condition” (f = 5) and “previous hospitalization experiences”(f = 2). In round 2, both the “child's clinical condition” and the “communicational approach to children” did not reach consensus and were rejected. All other items achieved a high consensus among nurses.

We can understand that the aspects identified by nurses that can function as constraints partially reflect the strategies presented. With regard to institutional and organizational aspects, these can be an obstacle to the child's greater participation in care28 and, therefore, a factor that generates dissatisfaction. Previous hospitalization experience was referred to as a difficulty. However, the literature highlights its positive impact on satisfaction with hospitalization both in adults and school children9. One possible explanation is that nurses consider that the previous experience may have been unsatisfactory and will condition their satisfaction with the new hospital experience.

With regard to strategies that promote parents satisfaction with care with, nurses identified, in the first round, 12 strategies that achieved consensus in round 2.

Thus, the first strategy refers to “family involvement” (f = 29) and includes the activities: “encouraging care for children by family members during hospitalization” (f = 21) and “establishing a personal relationship with children and family members involved in care”(f = 8). Family involvement has already been identified as a predictor of parents' satisfaction with care27 and it is directly associated with the establishment of a partnership relationship with nurses. Discrepancies between what parents expect to be able to do at the hospital and what they actually do increases the risk of dissatisfaction and conflicts between parents and professionals29. The concept of parental participation in the care of hospitalized children includes negotiation and interaction between nurses and parents, agreement in clarifying their role and the degree of participation, training and parental involvement in care.

The second strategy identified by nurses in round 1, was the “transmission of information” (f = 23). It includes the activity “providing family / significant person with information about the illness and children hospitalization” (f = 23) which obtained, in round 2, a high consensus.

Family-centered care philosophy presupposes the permanent exchange of information between family members and professionals. Therefore, it appears identified as a strategy adopted by nurses in caring for families of hospitalized children30 however, the activities involved are not specified. It appears that the nurses in this sample value this area, either by the frequency with which it was identified, or by the level of consensus it obtained.

The third strategy identified was “support for the family” (f = 19) and follows on from the previous two. We emphasize that nurses identified the use of strategies directed to the family as a unit and not to the mother / father as an individual. Family support, during child hospitalization, involves providing information about the child's clinical situation, prognosis, treatment and care. When support and information are adequately provided, parents are able to successfully cope with hospitalization and support the child, but also the rest of the family. Support can take several forms: informational support that is operationalized in the communication of relevant and perceivable information by parents, emotional support that consists of active listening and having behaviors that show concern in helping parents and instrumental support that includes assistance of any kind in managing the disease29.

In continuity, it was identified by nurses in round 1, the “use of communication strategies” (f = 7) with the activity: “showing interest in the family” (f = 7). This activity achieved a very high consensus in round 2 which reflects the central importance of communication.

It was also identified as a strategy “care in children admission” (f = 4) with two associated activities: “orienting patient / family / significant people regarding the expectations of care” (f = 3) and “offering appropriate privacy to the patient / family / significant (f = 1) that obtained, in round 2, a high degree of consensus. The child's admission to the hospital appears as a last resort when the necessary care cannot take place at home or as an outpatient. Privacy is valued by parents (29) but little emphasized by school aged children4.

The last strategy identified by nurses in round 1, was “family unity” (f = 3) and includes the activities “facilitating an environment of unity between family members” (f = 2) and “facilitating family visits” (f = 1). It is a strategy that fits into the strategies that aim at the family as a unit and that arises such as the strategies previously mentioned.

Finally, regarding the difficulties and constraints to the implementation of strategies that increase satisfaction among parents, 6 items were identified by nurses.

Nurses identify the “lack of resources” (f = 41), also categorized in: “time resources” (f = 18), “material resources” (f = 7) and “human resources” (f = 16). In round 2, the item “material resources” was rejected due to lack of consensus and the remaining two items achieved a high consensus.

Similarly to what has already been mentioned, the lack of resources is clearly an aspect identified by parents and nurses in the literature.

Finally, it was also identified, in round 1, the “institutional and organizational aspects” (f = 13), which was rejected in round 2, the “communicational approach of parents” (f = 10) and “previous hospitalization experiences” (f = 1) who achieved high consensus in round 2.

It appears that among the suggested strategies, no aspect related to the nurses' personal characteristics was identified despite being an attribute valued by parents and children. On the other hand, despite the lack of time resources mentioned, time management does not appear as a strategy either.

As limitations to this study, the rate of return stands out, which, being one of the limitations in this technique, may have influenced the strategies suggested by nurses.

CONCLUSIONS

This study allowed the identification of strategies to be implemented to increase the satisfaction of children and parents with nursing care during hospitalization. It appears that there is no alignment between the aspects valued by children, parents and nurses, which demonstrates the need to include all stakeholders in the research work. On the other hand, the valorization of the family as an integral part of pediatric care is very evident in the suggested strategies. It drifts from the philosophy of care used in pediatric healthcare and accepted as the best practice.

The identification of these strategies enables a nursing intervention more directed at customer satisfaction based on scientific knowledge.

AgradecimientoThis work is funded by National Funds through the FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., within the scope of the project Refª UIDB/04279/2020

REFERENCES

1. Ng JHY, Luk BHK. Patient satisfaction: Concept analysis in the healthcare context. Patient Educ Couns [Internet]. 2019 Apr [cited 2019 Jun 11];102(4):790-6. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0738399118310048 [ Links ]

2. Folami F. Assessment of Patient Satisfaction with Nursing Care in Selected Wards of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital (Luth). Biomed J Sci Tech Res [Internet]. 2019 Apr 15 [cited 2019 Oct 5];17(1). Available from: https://biomedres.us/pdfs/BJSTR.MS.ID.002941.pdf [ Links ]

3. Karaca A, Durna Z. Patient satisfaction with the quality of nursing care. Nurs Open [Internet]. 2019 Apr 4;6(2):535-45. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30918704 [ Links ]

4. Loureiro F, Figueiredo MH, Charepe Z. Nursing care satisfaction from school-aged children's perspective: An integrative review. Int J Nurs Pract [Internet]. 2019 Jul 17 [cited 2019 Jul 18]; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12764 [ Links ]

5. Tsironi S, Koulierakis G. Factors affecting parents' satisfaction with pediatric wards. Japan J Nurs Sci [Internet]. 2019 Apr 25 [cited 2019 Dec 3];16(2):212-20. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jjns.12239 [ Links ]

6. Coleman LN, Wathen K, Waldron M, Mason JJ, Houston S, Wang Y, et al. The Child's Voice in Satisfaction with Hospital Care. J Pediatr Nurs [Internet]. 2020 Jan;50:113-20. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2019.11.007 [ Links ]

7. Loureiro F, Charepe Z. How to improve nursing care? Perspectives of hospitalized school aged children parents. In: Annals of Medicine [Internet]. 2018. p. S160. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07853890.2018.1427445 [ Links ]

8. Loureiro F, Charepe Z. Hospitalization of school age children - parents satisfaction with nursing care. In: Annals of Medicine [Internet]. 2018. p. S160. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07853890.2018.1427445 [ Links ]

9. Pelander T, Leino-Kilpi H, Katajisto J. Quality of Pediatric Nursing Care in Finland. J Nurs Care Qual [Internet]. 2007 Apr;22(2):185-94. Available from: http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00001786-200704000-00016 [ Links ]

10. Loureiro FM, Araújo BR, Charepe ZB. Adaptation and Validation of the Instrument ' Children Care Quality at Hospital ' for Portuguese. Aquichan [Internet]. 2019 Dec [cited 2020 May 27] ; 19( 4 ): e1947. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1657-59972019000400107&lng=en. http://dx.doi.org/10.5294/aqui.2019.19.4.7 [ Links ]

11. Rodrigues MJB, Dias MLS. Satisfação dos Cidadãos face aos Cuidados de Enfermagem - Desenvolvimento de uma escala e resultados obtidos numa amostra dos Cuidados Hospitalares e dos Cuidados de Saúde Primários da Região Autónoma da Madeira. Funchal; 2003. [ Links ]

12. Keeney S, Hasson F, Mckenna H. The Delphi Technique in Nursing and Health Research. 1a. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. 198 p. [ Links ]

13. Masters K. Nursing Theories: A Framework for Professional Practice. Burlington: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2015. 406 p. [ Links ]

14. Smith NR, Bally JMG, Holtslander L, Peacock S, Spurr S, Hodgson-Viden H, et al. Supporting parental caregivers of children living with life-threatening or life-limiting illnesses: A Delphi study. J Spec Pediatr Nurs [Internet]. 2018 Oct 28;(March):e12226. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/jspn.12226 [ Links ]

15. Foth T, Efstathiou N, Vanderspank-Wright B, Ufholz L-A, Dütthorn N, Zimansky M, et al. The use of Delphi and Nominal Group Technique in nursing education: A review. Int J Nurs Stud [Internet]. 2016 Aug 1 [cited 2020 Feb 7];60:112-20. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0020748916300359 [ Links ]

16. Trevelyan EG, Robinson PN. Delphi methodology in health research: how to do it? Eur J Integr Med [Internet]. 2015 Aug;7(4):423-8. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1876382015300160 [ Links ]

17. Bardin L. Content Analysis. Lisboa: Edições 70; 2013. 281 p. [ Links ]

18. Campos CJG. Método de análise de conteúdo: ferramenta para a análise de dados qualitativos no campo da saúde. Rev Bras Enferm [Internet]. 2004 Oct [cited 2017 Mar 26];57(5):611-4. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/reben/v57n5/a19v57n5.pdf [ Links ]

19. Bulechek GM, Butcher HK, Dochterman JM, Wagner CM. Classificação das Intervenções de Enfermagem. 6a Edição. Philadelphia: Elsevier Editora Ltda.; 2016. 1393 p. [ Links ]

20. Marcinowicz L, Abramowicz P, Zarzycka D, Abramowicz M, Konstantynowicz J. How hospitalized children and parents perceive nurses and hospital amenities: A qualitative descriptive study in Poland. J Child Heal Care [Internet]. 2016 Mar 21;20(1):120-8. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1367493514551313 [ Links ]

21. Cimke S, Mucuk S. Mothers' Participation in the Hospitalized Children's Care and their Satisfaction. Int J Caring [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Aug 26];10(3):1643-51. Available from: http://www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org [ Links ]

22. Shevell M, Oskoui M, Wood E, Kirton A, Van Rensburg E, Buckley D, et al. Family-centred health care for children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol [Internet]. 2019 Jan 7;61(1):62-8. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/dmcn.14053 [ Links ]

23. Schleisman A, Mahon E. Creative Play: A Nursing Intervention for Children and Adults With Cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs [Internet]. 2018 Apr 1;22(2):137-40. Available from: www.tdi-dog.org/Default.aspx [ Links ]

24. Lopes F, Nascimento J, Cartaxo L. A influência da recreação terapêutica frente à recuperação da criança hospitalizada. Rev UFG [Internet]. 2018;24:426-7. Available from: https://www.revistas.ufg.br/revistaufg/article/view/58630/33137 [ Links ]

25. Caleffi CCF, Rocha PK, Anders JC, Souza AIJ de, Burciaga VB, Serapião L da S. Contribution of structured therapeutic play in a nursing care model for hospitalised children. Rev Gaúcha Enferm [Internet]. 2016;37(2). Available from: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/rgenf/v37n2/en_0102-6933-rgenf-1983-144720160258131.pdf [ Links ]

26. Gomes A. Boa enfermeira e bom enfermeiro: visão de crianças e adolescentes hospitalizados [Internet]. Universidade de São Paulo; 2018. Available from: http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/22/22133/tde-19032019-151746/en.php [ Links ]

27. Matziou V, Boutopoulou B, Chrysostomou A, Vlachioti E, Mantziou T, Petsios K. Parents' satisfaction concerning their child's hospital care. Jpn J Nurs Sci [Internet]. 2011 Dec;8(2):163-73. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1742-7924.2010.00171.x [ Links ]

28. Oulton K, Gibson F, Sell D, Williams A, Pratt L, Wray J. Assent for children's participation in research: why it matters and making it meaningful. Child Care Health Dev [Internet]. 2016 Jul;42(4):588-97. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/cch.12344 [ Links ]

29. Prasannan S, Thomas D. A Study to Determine the Level of Satisfaction of Parents with the Nursing Care for Children Admitted in Paediatric Oncology Ward and Seek its Association with Selected Factors in Selected government Hospitals of Delhi. Int J Heal Sci Res Nurs Off [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Jun 11];8(10):150. Available from: www.ijhsr.org [ Links ]

30. Ferreira L, Oliveira J, Gonçalves R, Elias T, Medeiros S, Mororó D. Nursing Care for the Families of Hospitalized Children and Adolescents. J Nurs UFPE Line [Internet]. 2019;13(1):23-31. Available from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e866/350dbbd38757b15d6d66d8fc400e4009e1e2.pdf [ Links ]

Received: May 27, 2020; Accepted: September 07, 2020

texto en

texto en