Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Enfermería Global

versión On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.21 no.68 Murcia oct. 2022 Epub 28-Nov-2022

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.502291

Originals

Adaptation experienced by families from diagnosis to treatment of the child's chronic condition

1Federal University of Pelotas. Pelotas – Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Objective:

To know the adaptation process experienced by families from diagnosis to treatment of the child's chronic condition.

Material and method:

This was a multicenter, qualitative study. Data presented refer to the collection carried out in the municipality of Pelotas, state of Rio Grande do Sul, in 2019. Participants were fifteen family members/caregivers of children with chronic conditions admitted to pediatric units in hospitals. Semi-structured interviews were applied and the information was analyzed through thematic analysis and interpreted using the theoretical framework: The Nursing Theory - Roy's adaptation model.

Results:

The group of participants was composed of ten mothers, three fathers and two grandmothers. Family members follow a trajectory in search of the child's diagnosis, facing difficulties in this experience, such as the impact of the diagnosis, risks, and repercussions of the disease, as well as the lack of information and ineffective communication between professionals and family members, in addition to difficulties in moving to the treatment site.

Final considerations:

It is necessary to critically reflect on the approach to families of children with chronic conditions, aiming at identifying the situations of vulnerability faced so that professionals can serve them, striving for comprehensive care based on their demands. Furthermore, it is essential to adopt effective communication, improving the work process to stimulate dialogue and understanding with families about the diagnosis, risks, treatment, and consequences of the child's chronic disease.

Keywords: Family; Child; Chronic Disease. Nursing Theory

INTRODUCTION

From the perspective of Roy's Adaptation Model1, each person uniquely experiences the adaptation processes to which they are exposed, since for the theorist the person is understood as an adaptive system, which constantly responds to stimuli from the internal and external environment. When a child experiences the process of becoming ill and facing the diagnosis of a chronic condition, they, like their family, needs to rethink and reorganize their life so that a return to balance is possible.

Chronic illness in childhood impacts the life of the child and their family, as it is not expected the experience of illness and the discovery of a condition that will accompany the child for a long time, or for a lifetime2. The diagnosis of a chronic condition in childhood is accompanied by the need for a series of adaptations to meet the care demands arising from the child's new existential condition, such changes are related to the way those involved understand the world and relate to society3.

This context generates reactions in the family under specific circumstances, such as changes arising from the existential condition of the child, which results in the behavior verified through an adaptable response, which promotes in the family the integrality, survival and growth in the face of the situation. Moreover, it can generate an ineffective response, which does not contribute to the adaptation of the lived moment, threatening survival, growth and mastery of what surrounds the child1.

Children and their families experience moments of insecurity and fear since the search for diagnosis, during it and after, due to the uncertainty of what life will be like from then on4. The diagnosis of the chronic condition is, in most cases, difficult and time-consuming. The family and the child take long to obtain it and for treatment, going back and forth to many health services, looking for the resolution of their problems (5)(6. This whole process makes the child and the family need to adapt and this does not happen “magically”, that is, in order to maintain their integrity, adaptation must occur in all the situations presented.

It is noteworthy that children with a chronic condition and their families need to adapt to the need to seek different health and education services, financial changes, food, and their routines7. Experiencing, positively, the process of adaptation to the child's chronic condition can be facilitated according to Roy's adaptation model1 through support networks, which are considered responsible for the human being's ability to adapt.

Based on the above, it is necessary to expand knowledge about the process of adaptation of these families and children to diagnosis and treatment, aiming to develop strategies to provide more adequate care to their demands, as well as to minimize the negative effects of chronic disease in their lives. Therefore, the following research question was elaborated: What is the adaptation process experienced by families from the diagnosis to the treatment of the child's chronic condition? And as an objective: Knowing the adaptation of families from diagnosis to treatment of the child's chronic condition.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Type of study

This was an exploratory, descriptive, qualitative, multicenter research, developed in four municipalities in the state of Rio Grande do Sul (Porto Alegre, Santa Maria, Palmeiras das Missões and Pelotas) and one municipality in the state of Santa Catarina (Chapecó), entitled “Vulnerabilities of children and adolescents with chronic disease: care in a health care network”, and the information presented here refers to the collection carried out in the Pelotas, state of Rio Grande do Sul.

Research participants

Participants were fifteen family members/caregivers, including ten mothers, three fathers and two grandmothers. The information reached saturation, as no new element was found in the speeches of new participants, and it was not necessary to add new information to understand the phenomenon studied8. Inclusion criteria were: being a family member/caregiver of a child aged six to 12 years diagnosed with a chronic condition. Family members/caregivers of children in palliative care or in critical life situations were excluded.

Data collection

As this was a qualitative study, it was designed to meet the checklist of recommendations of the Consolidated Criteria for Qualitative Research Reporting (COREQ)9. Information was collected by the members of the Research Group in the municipality of Pelotas, who were previously trained. The collection took place in the homes of family members/caregivers, and the meeting was previously scheduled with each participant.

Information was collected in 2019, with family members/caregivers of children with a chronic condition admitted to pediatric units of the three public hospitals in the municipality, two hospitals with care for members and patients of the Unified Health System (SUS) and one exclusively with assistance from the SUS. Semi-structured interviews were applied, with open and closed questions about the perspective of family members/caregivers on the experience of the child's chronic condition. These had an average duration of 60 minutes, were recorded on a cell phone and transcribed in full, manually (with double checking).

Data analysis

Information was deductively analyzed, through thematic analysis, a method used to identify and analyze themes of the information collected, and from the themes arising, organize and describe the information in detail, and interpret aspects of the research topic10.

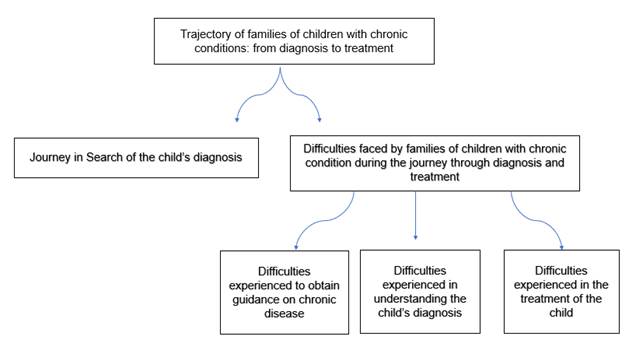

Thematic analysis10 consisted of six steps: (1) approximation with the transcribed information, through reading and re-reading; (2) formation of initial codes, with the objective of assigning meaning to them in a systematic way, among similar meanings; (3) association of themes, defining names and organization of the most relevant information according to the guiding question; (4) confirmation of themes according to coding and creation of thematic map; (5) constitution of the names of the themes, through the final analysis of the themes listed; (6) extraction of results, formation of the analysis report encompassing what is essential about the information10. The constructed thematic map is presented below.

Also, for interpretation of information, the Nursing theory - Roy's adaptation model1. was used as a reference. Conceptualizing the person considered in this study as the family member/caregiver, this theory is a holistic and adaptable system, in which the input, through stimuli, activates regulatory and cognitive mechanisms with the objective of maintaining adaptation; and the outputs of people (family members/caregivers), as systems, are their responses, that is, their behaviors, which in turn become feedback for the person and the environment, being categorized as adaptive responses.

When considering that the same stimulus causes different behaviors in individuals, as it is related to intrinsic coping factors, Callista Roy's theory allows to recognize that people who experience a disease, through stimuli, can trigger responses, sometimes adaptive, sometimes not10.

In this context, such stimuli can be focal, residual and contextual and go through adaptive modes, namely: the physiologic mode, aimed at meeting basic needs to maintain the person's physiological integrity; the role function mode that identifies the patterns of interpersonal relationships reflected by roles people assume; the self-concept mode, aimed at meeting psychic needs; the interdependence mode, in turn, acts on affective needs, identifying patterns of human value, affection and love1. From the input of the stimuli, going through the adaptive modes, the family members will have the output, in other words, their behavior in the face of the lived moment.

Ethical procedures

The ethical precepts recommended in Resolution 466/1211 were respected, and information was collected after approval by the Research Ethics Committee under opinion number 1.523.198 CAEE 54517016.6.1001.5327. Participants were asked to sign the Informed Consent, which contained the research objective, its risks and benefits. In addition, the confidentiality of interviewees and interviewees was maintained, using the consonant “F” (Family) followed by a sequential numeral (F1, F2, F3...) to name them.

RESULTS

Regarding the profile of family members/caregivers, 12 were female and three were male. The age ranged from 25 to 68 years old, with regard to schooling, six participants had incomplete elementary school, three had incomplete high school, two had complete high school, one was illiterate, one had complete elementary school, one had complete higher education and one had incomplete graduate degree. Family income ranged from R$937.00 to R$5,080.00. As for marital status, nine caregivers/family members lived with a spouse/partner, four were single and two were separated/divorced/widowed.

Among the diagnoses of the children were: sickle cell anemia, thalassemia, asthma, kidney damage, cerebral palsy, West syndrome, hydrocephalus, myelomeningocele, diabetes mellitus, Williams syndrome, autism, phenylketonuria, osteomyelitis, congenital hypothyroidism and Down syndrome.

Journey in search of the child's diagnosis

In order to find the correct diagnosis for the child, participants revealed that was is necessary to go through a long, time-consuming journey, with many obstacles to be faced. In this process, families were faced with the focal stimulus, which is permeated by an initial event, which calls their attention, evidenced by the situation in which, when seeking care at the health service, the child's demand cannot be met at that level of care, thus, they were referred to other services that could be effective for that case, prolonging the journey in search of a diagnosis.

She started to pee a lot, then we consulted, went to the hospital, through the Emergency Room and then they sent her to the hospital and she was already admitted there. (...) she urinated a lot, was very thirsty and previously had a urine infection, I don't know if it was a triggering factor or not (...). then she stayed at (name of the hospital), underwent the treatment, was hospitalized, she was diagnosed there, her physician from then on started to treat her and I think she is the same until today. (F7)

First, my wife got suspicious, she looked for a pharmacy where she took the exam right there in the pharmacy. The result was altered, the sugar (glucose) was very high and then she asked us to go to the UPA (Emergency Care Unit). (...) after the UPA they sent us to the hospital. (F12)

In F5's speech, it can be seen that several referrals were made, passing through services at the primary, secondary and tertiary levels of health care, experiencing diagnoses and hospital stimuli, confronting the family with focal stimulus, and when arriving at the hospital level (tertiary), finally the child received the real diagnosis of his health condition.

First, we went to the Basic Health Unit. And from there, we went to the ER (Emergency Room), at the ER, they did tests on her, and they thought it was appendicitis. But, I didn't let them to perform surgery or anything until they referred us to (name of hospital) where they saw that it was a kidney infection. (F5)

On the other hand, the speech of F13 refers to an even longer path, here transpiring in addition to a focal stimulus, the contextual stimulus, because in this case it starts with the first consultation, still without diagnosis, and the patient is discharged home. Then, the aggravation was experienced, returning it's a trajectory in a search for a diagnosis by various health services, in which the family was faced with a context that is no longer strange, the contextual stimuli are evidenced by the feelings experienced, care environment, the individuals who compose them, making this trajectory even more distressing in the face of non-resolution.

(...) the first time we saw this, I took him (the child) to the ER (Emergency Room) and there they cleaned it and said there was nothing there, it was fine. They sent us home. We came home. (..) the welt and fever began to rise. (...) then I took him back (...). they thought it was better to start with antibiotics to try to fight the fever (...). They gave him a lot of medicine. And they sent us to (name of hospital) to have a drainage done, but when they did the drainage there (name of hospital), they were supposed to have scared that bone and they did not, they just drained it and sent it away. Then it took a very long time for me to get another service for him. Because when I took him (the child) to the visits where he did the drainage. (...) the physician told me that his foot was fine, it was normal, that with time it would get better, that it was normal. (...) and I would say “Doctor, he has edema” and he couldn't wear a flip-flop, a sock, nothing. “Hey mom, this is normal” (...). But he was having fever, he was in pain and the physician said that this was all normal, that it would pass with time, that there was nothing else to do, it was just drainage, that's it. I went home with him, and he continued to feel pain and then after about three months it didn't cease. Then I took him to (name of hospital). (...) the physician (physician's name) who saw him, said “mother, his foot has a big mistake, but I can't do nothing, I didn't do it, so I don't know what they did there inside. No physician will treat others mistake.” Then I said to him, “Okay, but so what, what about my son now?” “No, you have to look for the physician who made the mistake”. I went to look for, where is the physician? (...). Later, with the time I went to the prosecutor's office, to the child protection council, and then I managed to get him treated there (name of hospital), fighting, because no one wanted to attend. (...) when I brought the history, he said “he even had a biopsy, look here” and the biopsy had already said that he had osteomyelitis and no one told me anything, and no one even treated him for that. (F13)

In this speech, the delay and the long journey necessary to diagnose the child with a chronic disease is evidenced. The stimuli shown here lead the family to the adaptative mode of self-concept, developing a resistance mechanism that will generate an adaptative response or not, this mechanism allows the person to increase or decrease efforts to deal with the stimuli, thus, in the face of the trajectory in search of the son, it was shown that they only increased their efforts in pursuit of the goal and did not give up until they found the resolution.

Difficulties experienced to obtain guidance on chronic disease

Among the difficulties experienced by family members regarding the diagnosis of the child's chronic condition, there is the difficulty in having guidance on the disease the child has and how to perform the care.

The participants' reports express the experience of moments of surprise and uncertainty regarding the diagnosis and the child's future. These uncertainties are even greater because information about the condition, the diagnosis and its possible repercussions for the children's lives are often lacking, making family members even more apprehensive about the future of these children and surprised when any complication occurs before the diagnosis, thus, the family members are stimulated in a focal way:

But they never told me about the risk of stroke (Cerebral Vascular Accident). When stroke happened, it was a scare for me, because until then I had no idea. (...) it was a surprise. (F1)

Oh, it was right when he was born (...) we spent a month in the hospital, in the ICU (Intensive Care Unit). But there, they lied a lot to us in the hospital, because it was even a mistake in the delivery, he was born at eight months, umbilical cord circular, they took a long time to deliver him too (...). After two days, he got an infection, he got meningitis, they told us that he would just keep pulling a crooked arm, a crooked leg, that's what they told us. But when we went to Porto Alegre (capital), the first time we consulted there (...). The physicians were terrified, they already referred us there, they said that if he hadn't been here, they wouldn't believe he would be alive because of the damage that was left in his brain. (...) this is serious, it is nothing like what they told you, the case is serious. (F3)

But there was nothing else, even the ultrasound did never show what she had (...). When she was born, we knew about her illness (...). Ease has none and difficulty has a lot (...). (F6)

Nobody said anything to me, and nobody even treated him. (F13)

Difficulties experienced in understanding the child's diagnosis

Faced with the diagnosis of chronic disease in childhood, the difficulties experienced by families in understanding the diagnosis were evidenced:

They just said that she had that disease, that's why she cried. (...) that there was a right position to sleep too, that's what they said (...). The treatment (...) at first, they talked about nebulization because she was too young, in this case, to use the pump. (F4)

(...) because it is difficult, his illness, for us, is always there, always on us (...) we always have to be very alert (...). This disease will remain like this for the rest of his life. (...) a child like this is very delicate. You always have to see a physician, every three months you have to. (...) I don't know, I just know to say that we always treated him, he always takes the same medication. (...) every month he goes, he is attended to (F9)

(...) it's even in the past, but it's just that they pass on so much information and we don't understand anything about the disease that we're slowly crawling and learning, what happens, we hear a lot about the story of those who already have it, and we are learning little by little. A lot of things I don't know, I'm learning little by little because if we search the internet, there is a lot of information, then I think it's even worse. (...) until now I don't understand what ketoacidosis is, they explain it and each one explains it in a different way. (F11)

The only information in this case is that he has to undergo surgery (...). He has (...), I don't know the name of the disease. (...) it's a murmur, like a murmur, I don't know how to name the disease. (F14)

In the reports, professionals provide information about the diagnosis, but often, the family has difficulty in understanding what they were told about the condition. Or even, the information does not demonstrate clarity about the real condition of this child. The family understands that it is a chronic condition, which requires treatment and continuous monitoring with health professionals, but the understanding is limited, to the point that they do not show a detailed understanding of the child's clinical condition, the needs and limitations that this child may have.

The limited understanding on the part of family members is crossed by the focal stimulus, to the point where a diagnosis is defined, but also residual, as the diagnosis. However, there is no effective communication between family members and health professionals, which brings memories of previous problems, thus, transversally generating an adaptative mode of interdependence, which is characterized by the dependence between the parties. In this, for communication to be effective, it needs to be clear, providing security to the context of understanding for family members.

Difficulties experienced in the treatment of the child

Even with the diagnosis defined, the family starts a new journey with the child, now looking to provide the appropriate treatment that the chronic condition requires. Adding to the uncertainties and lack of information, families go through several health services and professionals in which it is often necessary to travel to other cities to follow up on adequate treatment for the child, which is pointed out as a great difficulty.

In this context, residual stimuli are observed, which are environmental stimuli inside and outside the person, whose effects of the situation are not central, thus, what was supposed to be central, the child's health condition, becomes non-resolving of the case with the pilgrimage through various services. Thus, the person may not be aware of the influence of these factors, or it may not be clear to what extent they influence the individual. In addition, this stimulus also interacts with the role-function adaptive mode, because although family members are the main caregivers, they depend on the direction and care of health services and professionals for their resolution.

(...) for the treatment, we went first to the Specialty Center, then the physician was on maternity leave at the time and we went to Porto Alegre (capital) to research where it came from, to do all the genetic tests (...). (F1)

We took him (child) there (Basic Health Unit), then they referred him there (Emergency Room) which was the hospital where he was a child. Then we took him and he was admitted, he stayed there for about four days and then they transferred him to the (Municipal Hospital) (...). Ah, since he was little, sometimes he was a year old, and then he remained at home for a week and go again (...). (F2)

He was taken here at (name of the Basic Health Unit), then he consulted, the physician said he had to use a pump, but it was a crisis like that, it was not such a severe crisis. (...) so he did this treatment, (...) and the crisis ceased (...) after he had these two times, he had the strongest crisis. (...) then he had to go to the ER (Emergency Room) and there he was admitted. He had to be hospitalized, then he went to (Municipal Hospital) and then referred to the School (Outpatient clinic of the Medical School). (F8)

We found out from the clinic (Basic Health Unit), no, not from the clinic, she did the heel prick test four days later, she repeated three more exams at the Specialty Center, then we concluded what she had when she was one month old. That's when we already found out there in Porto Alegre (Capital). The physician, when her last result came, we already came with the appointment scheduled and, until then, at the time when she was born, there was no information about the disease. (F10)

(...) the referral to the School (Outpatient clinic of the Medical School), but the referral to the school I never got, I even tried by phone, but they didn't (...). The phone was always busy and the two times I managed to go there; the numbers had already been passed (...). There is no way to have follow-up, there is no follow-up (...). The numbers, which are few, right? There aren't many, and it's not every day that they give away numbers. It's just one day, if you miss that day you wait until another month to get it. (F15)

Based on the speeches presented, the long journey that is initially taken by the relatives of children with a chronic condition for the care and the diagnosis, through various health services, is identified. This process is permeated by difficulties regarding care, the definition of the diagnosis and new information about the clinical condition generates surprises and uncertainties in relation to information about risks, possible complications the child has or may have. Another complicating factor governs the family's lack of understanding of the child's real condition and its treatment, which demonstrates a failure in communication between professionals and families.

Thus, what is focal, at a given moment, will become contextual, and what is contextual may become residual. In addition, the stimuli come together to form the adaptation level, a turning point that represents the person's ability to respond positively to a situation. Within the framework of the model, responses to stimuli are not limited to problems, but on the contrary, the model integrates all responses of the adaptative system. These responses are called behavior.

DISCUSSION

The research in question highlights the long journey taken by families in search of a diagnosis for the child, which delays adequate treatment, often worsening the child's clinical condition. Corroborating these findings, a study shows that the search for the correct diagnosis of a chronic condition in childhood can be time-consuming, characterized by several visits to different health facilities, which are often not resolute, making the path distressing for the family12. The delay causes the family to experience feelings of anxiety, fear, guilt and suffering, in addition, the inaccurate diagnosis can prolong and aggravate the child's symptoms, thus generating complications in their health status13.

In the functioning of the adaptative system, a system is defined as something that influences all adaptive modes, with a set of interconnected parts that, in addition to being a whole and having relates parts, also have inputs, outputs, response and control processes. The inputs are the stimuli and can originate externally, from the environment, and internally. The person's response is the output, so this may or may not be an adaptable behavior1.

In view of the above, in the trajectory of families through the health services, as their inputs that are stimuli can be visualized externally by the various health services they went through, and internally by the anguish experienced effectively when not obtaining a resolution of the child diagnosis, this stimulus is called focal stimulus, as it confronts the family in the act, in an event that calls their attention.

According to a study14, most of the time, health professionals are not prepared to diagnose a chronic disease in childhood, the existence of peculiarities generates fear and insecurity. It is considered that this population needs continuous care, highlighting the need for professionals to be prepared and trained to provide quality and resolute care to children with chronic diseases and their families.

This research demonstrates the difficulty in diagnosing and treating children early, harming their physiologic mode, leading families to take a long journey in search of their goal. It is important to note that, in some cases, the signs and symptoms of childhood diseases may not be very specific, this concerns several different diagnoses. In addition, early diagnosis, when dealing with children, is usually difficult to obtain15.

Seeing the sick child and not knowing the reason causes feelings of surprise, impotence and uncertainty in the family, the lack of knowledge of the diagnosis leads families to experience anguish in relation to the fear of the unknown, fear in the face of countless possibilities of diagnoses. Thus, without the necessary answers, families travel back and forth to health services. The journey of comings and goings to health services happens because there is no diagnosis, despite efforts, it is something that does not depend on the family, but on health professionals. This process is initiated by a contextual stimulus, which is present in the situation, in the environment, in individuals and which interconnects everything that is in the context. Such stimulus enters the role function mode, which includes the patterns of interpersonal relationship, reflected by the role of the main caregiver who has mastery of what happens and who, at this moment, is at the mercy of not being the protagonist of care. However, this does not prevent them from continuing their search, demonstrating in this mechanism an adaptable response to the moment experienced1.

The fact that family members have a long journey in search of the diagnosis creates difficulties for families, due to the focal stimulus that directly interacts with the self-concept mode within their adaptation process, as the self-concept is directed to meeting their psychic needs, focusing on psychological aspects1 that with the impacting situation, triggers uncertainties and fears about the future of the child, having as an output/behavior an ineffective response.

When receiving the diagnosis of the child's chronic illness, feelings of fear, guilt and anguish are inevitable, because it is something unknown, the uncertainty of what the future will be like causes these feelings16. Adapting to chronic illness in childhood is an arduous process. In this sense, family reorganization is inevitable and constant in view of the diagnosis and necessary care for the child with a chronic condition, requiring changes in the routine. The family undergoes this reorganization, which is a crucial part of the child's development, providing values, beliefs, rules, customs and behaviors17.

Upon receiving the diagnosis of the child's chronicity, the family has to understand it, which is essential, because the sooner this occurs, the earlier will be the stimuli and care for the child's development. For this to be possible, bonding and dialogue with the family is necessary18.

In the reports of this study, family members often receive information about the condition and care, but they do not always understand this. This because there is a lot of information and often complex. Participant F11 says that she learned over time, in daily life, living with the child's condition, leaving the family more vulnerable individually and socially in relation to the child's chronic illness.

Communication can be described as an optics of response as a contextual stimulus, since the mechanism facing the adaptive result is correctly used, however, if used incorrectly, a response will have the opposite effect executing an inefficient result.

Importantly, it is essential to create a bond between the family and health professionals, aiming at humanized care, with quality and responsibility and that is resolute. Often, information on care, illness and its repercussions are lacking in the reception, which leaves caregivers with many doubts19. In health, communication is a fundamental process, and attention must be paid to the way in which information is transmitted to patients and their families, being necessary, on the part of the health team, concern to make adaptations in communication according to the level of understanding of who receives the information20.

Often, information and guidance about the disease and care are only given verbally and with a prescription for medication, if necessary, but this is insufficient, as family members are scared or do not understand the terms used by professionals. Moreover, there is no feedback on what the patient and caregiver understood about the information given. Another relevant point is the involvement of the patient and the caregiver in planning care, which is consistent with their reality and what will be carried out effectively, this facilitates their understanding, reduces treatment abandonment and thus, consequently, decreases future hospitalizations. It is important the multidisciplinary team is present at this time, meeting all the care demands of the individual as a whole21.

Therefore, when communication between professionals and the family is clear, using easy-to-understand terms, demonstrating the child's real clinical situation, explaining each stage of treatment and answering questions that arise, communication influences the effective adaptation of family members, reducing psychological distress, as it promotes trust and security22.

In view of the above, we emphasize the need to train professionals for quality listening to caregivers, as well as for clear communication between family members and professionals, in order to offer emotional support and clarify doubts regarding the pathology, care and possible complications, thus minimizing the vulnerabilities of families12.

Effective communication with the health team facilitates the adaptive process of family members22. In this sense, nursing is responsible for providing adaptive responses and minimizing ineffective ones, prioritizing the integrality of the person, thus allowing their system to be unaffected and hospitalization to take place in a way that the feelings of fear and anxiety are minimized1, regarding the lack of communication.

Information and understanding of caregivers about the disease and care is essential, and it is necessary to provide easy-to-understand and objective guidelines, in addition to offering a support network in the health system. Dialogue between family and health professionals is necessary, but this must occur clearly, because often, guidelines are provided to the family without their understanding, in this sense, it is important to listen to the family to know their understanding of what was said23. Without this, the entire journey becomes more difficult and uncertain, fostering insecurity and anxiety for those involved in care.

Ineffective communication between health professionals and family represents a threat to the integrality of care, which directs the family's adaptive process to be ineffective, as communication is associated with the relationship of dependence between people. At that moment, family is faced with a residual stimulus that encompasses environmental factors inside and outside the person, whose effects of the situation are not central, and refer to something that happened before, and is residually in the person's memory. The person (family members) may not be aware of the influence of these factors, or may not be clear to what extent they influence1.

In this way, the residual stimulus due to ineffective communication refers family members to the experience of when they did not really know the child's diagnosis, which leads them to a mode of interdependence, which is understood as giving and receiving respect, value and provide security among individuals1. When families do not understand what is communicated (diagnoses, risks, care, treatment), it is understood that there is an ineffectiveness of dialogue, without interdependence between those involved, which does not provide the family with respect and security, making the response to the mechanism ineffective.

Faced with the diagnosis of a chronic disease in childhood, as soon as the family needs to start treatment actions for the child's chronic condition, they are often faced with specialized care that is outside the family's city of residence, which is considered a difficulty in the face of the expected displacement.

It can be a factor of difficulty to face a difficult family process, to present a factor of difficulty for its integrality and, thus, to present a difficult treatment for its integrality and, thus, to respond well to its familiarity in the face of the imposed circumstance1.

The adaptive mode of role function is visible, because despite the diagnosis, there is still a long journey in search of treatment, so, despite family members being the main caregivers, this role depends on referral and guidance from professionals and services.

Corroborating our findings, the family needs to take several comings and goings and, independently, seek a specialized and qualified service. Some chronic conditions have an uncertain course and, often, families are surprised during this journey. This uncertainty about the course of the disease causes fear and stress in the family24.

Therefore, it is understood that the adaptive modes of role function are highlighted - when the main role ins impaired by the delay in obtaining a diagnosis and knowing what treatment and care with the appropriate care that the child needs and rehabilitated the diagnosis is defined, but it is still hampered by the long trajectory in search of a treatment in the midst of many comings and goings of services; self-concept mode - referred when the psychological aspects of the family run in the family; and the inferred mode of interdependence -when there is no effective communication between professionals and the family, constituting important mechanisms for the family's behavior.

Thus, what is focal, at a given moment, will become contextual, and what is contextual may become residual. In addition, stimuli come together to form the adaptation level, a turning point that represents the person's ability to respond positively to a situation. Within the model framework, responses to stimuli are not limited to problems, on the contrary, the model integrates all responses of the adaptive system. These responses are called behavior1. Thus, when evaluating the behavior of families, the adaptation experienced, because, in all families, they will be adapted through adaptable stimuli, sometimes to all families, the response is adapted by stimulus and other alternatives.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The study made it possible to know the journey taken by families from diagnosis to treatment of the child's chronic condition. The process of searching for answers that families of children with chronic conditions face was evidenced, seeing the child sick and without proper treatment causes impact, despair and uncertainties to the family. And even when they get care at the health service, many families still face difficulties in having the correct diagnosis for the treatment of the child.

The fragmentation of health services is highlighted, which leads to discontinuity of care for the family and the child, causing a journey in search of care, causing negative impacts on the quality of life of children with a chronic condition. As well as the precariousness of effective communication between patient-family and health professional, which makes effective treatment difficult.

Another point found was the difficulty of families, who lived in other municipalities, regarding limited access to health services. In the results, the limitations the health services of these municipalities have to close a diagnosis were identified. Therefore, families receive stimuli that interact with adaptive modes, in some cases there is a behavior characterized as an adaptive response and in other moments ineffective, in these cases, it can be concluded they are situations experienced that do not depend on them, but rather stimuli promoted by the discontinuity of care, treatment and information that should come from health professionals.

The study brings contributions to the reflection on the approach to families of children with chronic conditions, helping health professionals to have a critical look at the subject, with the objective of identifying the situations in which families and children are, serving them with a view to comprehensive care, providing them with quality of life, thus understanding their needs. It also helps health professionals to identify when communication is ineffective, and can improve their work process in order to effectively improve dialogue and understanding with families about the diagnosis, risks, treatment and consequences from the child's chronic illness.

As limitations of the study, it is presented the fact of not being able to interview other members of the family nucleus and the difficulty of finding the families, because many live in rural areas, without exact indication of address.

REFERENCIAS

1. Roy C, Andrews HA. The Roy adaptation model. 3aed. Stamford: Applet Lang; 2009. [ Links ]

2. Jorge-Junior AF, Colares GC, Filho IBMR, Silva LS. Doenças crônicas não transmissíveis na infância: revisão integrativa de Hipertensão Arterial Sistêmica, Diabetes Mellitus e Obesidade. Saúde dinâmica. 2020;2(2):39-55. Disponível em: http://revista.faculdadedinamica.com.br/index.php/saudedinamica/article/view/36/41 [ Links ]

3. Ichikawa CRF, Santos SSC, Bousso RS, Sampaio PSS. O manejo familiar da criança com condições crônicas sob a ótica da teoria da complexidade de Edgar Morin. Rev.enferm. Cent.-Oeste Min. 2018;8:e1276. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.19175/recom.v8i0.1276 [ Links ]

4. Pimenta EAG, Wanderley LSL, Soares CCD, Delmiro ARCA. Cuidar de crianças com necessidades especiais de saúde: do diagnóstico às demandas de cuidados no domicílio. Braz. J. of Develop.2020;6(8):58506-21. Disponível em: https://www.brazilianjournals.com/index.php/BRJD/article/view/15052 [ Links ]

5. Neves ET, Okido ACC, Buboltz FL, Santos RP, Lima RAG. Acesso de crianças com necessidades especiais de saúde à rede de atenção. Rev. bras. enferm. 2019;72(Suppl 3):71-7. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2017-0899 [ Links ]

6. Lopes ACC, Nóbrega VM, Santos MM, Batista AFMB, Ramalho ELR, Collet N. Cuidado à saúde nas doenças crônicas infanto-juvenis. REFACS (online). 2020;8(Supl.2). Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.18554/refacs.v8i0.4286 [ Links ]

7. Freitas TAR, Silva KL, Nóbrega MML, Collet N. Proposta de cuidado domiciliar a crianças portadoras de doença renal crônica. Rev Rene (Online).2011;12(1):111-9. Disponível em: http://periodicos.ufc.br/rene/article/view/4192/3245 [ Links ]

8. Hennink MM, Kaise BK, Marconi VC. Code Saturation Versus Meaning Saturation: How Many Interviews Are Enough? Qual. health res. 2017;27(4):591-608. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316665344 [ Links ]

9. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. j. qual. health care.2015;19(6):349-57. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [ Links ]

10. Braun V, Clarke V, Hayfield N, Terry G. Thematic Analysis. In: Liamputtong P. (eds) Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Springer, Singapore. 2019;48:843-60. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_103 [ Links ]

11. Ministério da Saúde. Resolução n° 466, de 12 de dezembro de 2012. Aprova normas regulamentadoras de pesquisas envolvendo seres humanos. Diário Oficial da União. Brasília, DF, 2013 [ Links ]

12. Pedrosa RKB, Guedes ATA, Soares AR, Vaz EMC, Collet N, Reichert APS. Itinerário da criança com microcefalia na rede de atenção à saúde. Esc. Anna Nery Rev. Enferm.2020;24(3):e20190263. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/2177-9465-ean-2019-263 [ Links ]

13. Gomes GC, Moreira MAJ, Silva CD, Mota MS, Nobre CMG, Rodrigues EF. Vivências do familiar frente ao diagnóstico de diabetes mellitus na criança/adolescente. J. nurs. health. 2019;9(1):e199108. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.15210/jonah.v9i1.13393 [ Links ]

14. Favaro LC, Marcon SS, Nass EMA, Reis P, Ichisato SMT, Bega AG, Paiano M, Lino IGT. Percepção do enfermeiro sobre assistência às crianças com necessidades especiais de saúde na atenção primária. REME rev. min. enferm. 2020;24:e-1277. Disponível em: http://www.dx.doi.org/10.5935/1415-2762.20200006 [ Links ]

15. Frizzo NS, Quintana AM, Salvagni A, Barbieri A, Gebert L. Significações dadas pelos progenitores acerca do diagnóstico de câncer dos filhos. Psicol. ciênc. prof. 2015;35(3):959-72. Disponível em: http://www.dx.doi.org/10.1590/1982-3703001772013 [ Links ]

16. Souza RFA, Souza JCP. Os desafios vivenciados por famílias de crianças diagnosticadas com transtorno de espectro autista. Perspectivas em Diálogo. 2021;8(16):164-82. Disponível em: https://periodicos.ufms.br/index.php/persdia/article/view/10668 [ Links ]

17. Xavier DM, Gomes GC, Cazer-vaz MR. Sentidos atribuídos por familiares acerca do diagnóstico de doença crônica na criança. Rev.bras. enferm. 2020;73(2):1-8. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2018-0742 [ Links ]

18. Santos BA, Milbrath VM, Freitag VL, Nunes NJS, Gabatz RIB, Silva MS. O impacto do diagnóstico de paralisia cerebral na perspectiva da família. REME rev. min. enferm. 2019;23:e:1187. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.5935/1415-2762.20190035 [ Links ]

19. Silveira A, Neves ET. Estratégias para manutenção da vida de adolescentes com necessidades especiais de saúde. Research, Society and Development. 2020;9(6):e88963387. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.33448/rsd-v9i6.3387 [ Links ]

20. Nardi AC, Brito PT, Albarado ÁJ, Prado EA, Andrade NF, Sousa MF, Mendonça AV. Comunicação em saúde no Brasil. Rev. Saúde Pública Paraná (Online). 2018;1(2),13-22. Disponível em:https://doi.org/10.32811/25954482-2018v1n2p13 [ Links ]

21. Fontana G, Chesani FH, Menezes M. As significações dos profissionais da saúde sobre o processo de alta hospitalar. Saúde e transformações sociais. 2017;8(2):86-95. Disponível em: http://incubadora.periodicos.ufsc.br/index.php/saudeetransformacao/article/view/4230/4994 [ Links ]

22. Bazzan JS, Marten VM, Gabatz RI, Klumb MM, Schwartz E. Comunicação com a equipe de saúde intensivista: perspectiva da família de crianças hospitalizadas. Referência. 2021;5(7):e21010. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.12707/RV21010 [ Links ]

23. Lise F, Schwartz E, Milbrath VM, Castelblanco DC, Ângelo M, Garcia RP. Incertezas de mães de crianças em tratamento conservador renal. Esc. Anna Nery Rev. Enferm. 2018;22(2):e20170178. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/2177-9465-EAN-2017-0178 [ Links ]

24. Bolaséli LT, Silva CS, Wendling MI. Resiliência familiar no tratamento de doenças crônicas em um Hospital Pediátrico: Relato de três casos. Pensando fam. 2019;23(2):134-46. Disponível em: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1679-494X2019000200011&lng=pt&nrm=iso&tlng=pt [ Links ]

Received: November 23, 2021; Accepted: June 29, 2022

texto en

texto en