Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Enfermería Global

versión On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.22 no.72 Murcia oct. 2023 Epub 04-Dic-2023

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.565581

Originals

Spiritual Intelligence profile in Peruvian health sciences students

1San Luis Gonzaga National University (UNSG). Ica, Peru

Introduction:

Health science students have a duty to care for human health; therefore, it is necessary to ensure a humanistic education based on the development and cultivation of Spiritual Intelligence.

Objective:

To know the Spiritual Intelligence profile and its associated factors in Peruvian health science students.

Method:

A cross-sectional study was conducted, including 418 randomly selected students from nursing, medicine, dentistry, obstetrics, and pharmacy programs. A virtual survey was used to collect socio-educational and religious-spiritual variables. The profile of Spiritual Intelligence was assessed using the Spiritual Intelligence in Healthcare Practice Scale. Descriptive and multivariate analyses were performed using generalized linear models of the Poisson family to evaluate certain factors associated with a healthy profile of Spiritual Intelligence.

Results:

21.1% of participants maintain a healthy profile of Spiritual Intelligence; also, in the dimensions of Spiritual Experience in Practice (14.1%), Existential Thinking (18.9%), Transcendental Awareness (15.3%). Considering oneself a spiritual person (RPa = 4.77; 95% CI: 1.98-11.4) and daily prayer practice (RPa = 3.02; 95% CI: 1.54-5.92) and weekly (RPa = 2.30; 95% CI: 1.12-4.72) were associated with a higher healthy profile of Spiritual Intelligence. However, several variables were identified that presented an unadjusted association with a healthy profile of Spiritual Intelligence.

Conclusions:

The proportion of health science students with a healthy profile of Spiritual Intelligence is low; there are certain modifiable associated factors that could enhance Spiritual Intelligence.

Keywords: Intelligence; Spirituality; Consciousness; Health Science Students

INTRODUCTION

Spiritual Intelligence (SI), also referred to as Consciousness Intelligence by Becerra-Canales et al., has been scientifically studied for the past two decades and is gaining importance due to its direct link to health, well-being, happiness, humanization, learning, and improved performance in all aspects of life and work (1).

SI is the individual's capacity to reflect upon and properly manage their social qualities and competencies for personal, emotional, intellectual, and professional development. It is considered as "the intelligence of the soul, the intelligence of the deep self, the intelligence with which we ask fundamental questions and reconsider our answers" (2,3). It involves the ability to give profound meaning to life and reality, always connecting with feelings, values, and universal principles (3,4,5). In line with these arguments, SI falls within the theory of multiple intelligences (6,7).

The ninth multiple intelligence is not necessarily linked to religiosity, as its importance lies in being superior to specific beliefs or religions, becoming a spiritual dimension and the ultimate transcendent goal of an individual (8). In this sense, there is a consensus that individuals with an appropriate profile of SI are more likely to improve their interpersonal, occupational, social, emotional, and spiritual relationships, contributing to success in their personal, professional, academic, social, affective, and emotional lives, as well as their overall well-being and personal fulfillment (1).

Health science students (HSS) have a duty to care for human health, which entails deep reflection on their pre-professional health practice, learning processes, and interpersonal relationships. In the field of health sciences, a true holistic and humanistic education involves developing and nurturing SI in students (9,10,11).

Therefore, within the university context, a person's professional training should encompass a humanistic educational project, understood as the comprehensive or holistic development in its deepest and perfectible sense, focusing on their human condition and their deepest values (culture, justice, freedom, goodness, love, respect, hope, beauty, nobility, virtue, etc.), as well as their capacity for autonomous reflection, self-realization, and personal transcendence. This can be achieved by introducing SI as a cross-cutting strategy in the educational curriculum (12,13,14). However, in today's society and educational environment, SI is not well developed due to the dominance of materialism, perfectionism, lack of meaning, and lack of commitment.

Very little research has been conducted on the spiritual dimension of HSS, making it necessary to study the behavior of this variable. For these reasons, this research aimed to identify the profile of SI and its associated factors in Peruvian health science students.

METHOD

Study Design and Population

Cross-sectional study conducted from June to November 2022. The population (N=4,262) consisted of health science students from the National University San Luis Gonzaga in the province of Ica, Peru (Figure 1). Using the mathematical formula for finite populations, a sample size of 353 participants was estimated with a confidence level of 95%, population proportion of interest at 50%, and a margin of error of 5%. Accounting for a potential 18% loss to follow-up, the final sample size was determined to be 418 individuals, selected through random probability sampling. Both male and female health science students were included, while those with mental or organic pathologies that impeded expressing their opinions and those with a history of psychoactive substance abuse were excluded.

Variables, Instrument, and Procedures

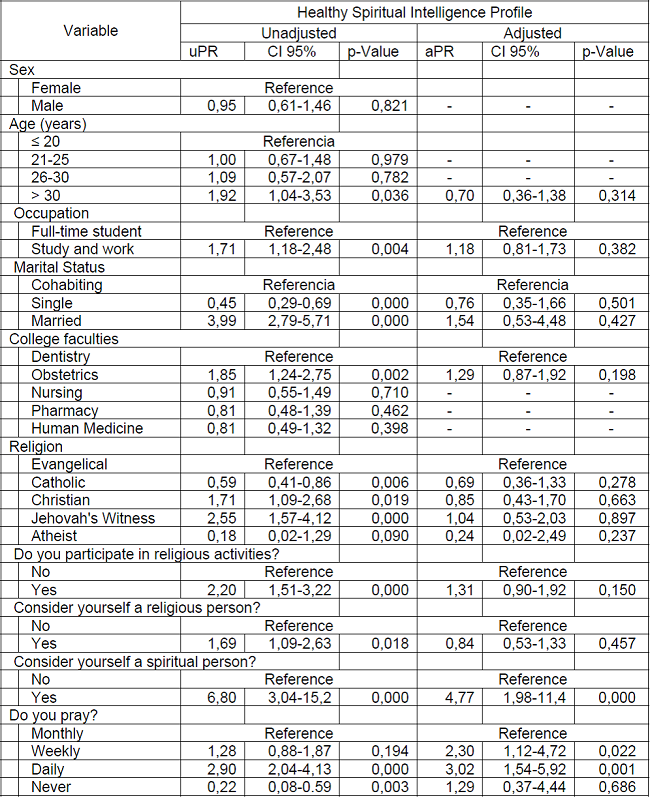

The variable Spiritual Intelligence was assessed using the Scale of Spiritual Intelligence in Health Practice (SSIhp) (15). It consists of 18 items and three dimensions: Spiritual Experience in Practice (SEP) (Items 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, and 17); Existential Thinking (ET) (Items 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, and 18); and Transcendental Consciousness (TC) (Items 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15). Since the instrument was not validated for health science students, minimal modifications were made to items 5 and 8 to improve students' understanding. "When I am engaged in the noble mission of my work practice (profession), my strength multiplies" was changed to "When I am engaged in the noble mission of my student and/or pre-professional practice, my strength multiplies" and "I believe that caring for my body and patients is a sacred duty" was changed to "I believe that caring for my body and/or the health of my patients is a sacred duty." Additionally, the response options were changed from "not at all true for me, somewhat true for me, mostly true for me, definitely true for me" to "Don't know/not at all/probably not/probably yes/definitely yes," with a scoring range of 0 to 4.

This proposed version was reviewed by a group of three professionals who were experts in the field. Subsequently, a pilot test was conducted with 42 students, and no additional modifications to the questions were made as a result of these procedures. The SSIhp scale, in its version for health science students (SSI/hcs), demonstrated adequate internal consistency for the overall scale with McDonald's Omega (ω = 0.901) and its dimensions: SEP (ω = 0.759), ET (ω = 0.769), and TC (ω = 0.756). A threshold was set using the mean global score + 1.5 standard deviations, where scores ≥ 64 points indicated a healthy or adequate Spiritual Intelligence profile, while lower scores indicated an unhealthy or inadequate profile. The same procedure was applied to the dimensions (15).

Socio-educational variables were included: gender, age (years), occupation, marital status, faculty of study, and religious-spiritual variables: religion, participation in religious activities, self-identification as a religious person, self-identification as a spiritual person, and prayer practice.

The information was collected through an online survey using a Google Forms questionnaire. Prior to data collection, the list of students was obtained, and coordination was made with the deans of the faculties involved in the study. With the support of secretaries, communication was established with the students through virtual means (emails, Messenger, WhatsApp, among others) to inform them about the purpose of the study, obtain informed consent for participation, and provide the URL where the instrument was located. They were instructed to complete the questionnaire and submit their responses electronically. Reminders were sent during the availability of the survey to follow up and motivate participation in the research.

Statistical Analysis.

The descriptive statistical analysis included measures of absolute and relative frequencies, means, and standard deviations. Differences were evaluated using the chi-square test, and generalized linear models from the Poisson family with a logarithmic link function were employed to assess the association between the main variable categorized as Healthy Spiritual Intelligence Profile (yes/no) and the socio-educational and religious-spiritual variables, previously dichotomized. Crude prevalence ratios (PRc) and adjusted prevalence ratios (PRa) with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. In the adjusted model, any variable with p < 0.05 in the crude model was included, taking into account the criteria of interest and availability (16). Data processing was performed using the statistical software "Statistical Package for the Social Sciences" for Windows version 25.0 in Spanish. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations.

The research was endorsed by the Ethics Committee of the San Luis Gonzaga National University (CEI-UNICA Nº 001/02-2023). Informed consent was obtained prior to enrolling participants in the study, and students in the health sciences were informed that their participation was voluntary and anonymous.

RESULTS

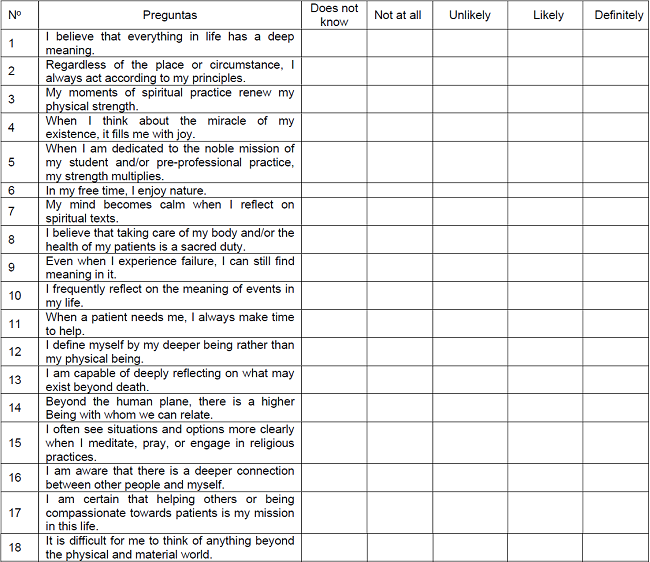

Among the participants, the majority were female (77.0%), aged 21 to 25 years (65.8%), full-time students (58.9%), single (90.9%), enrolled in the dentistry faculty (26.6%), identified as Catholic (73.7%), did not participate in religious activities (59.3%), considered themselves religious (63.9%), considered themselves spiritual (66.7%), and practiced prayer on a weekly basis (31.8%). (Table 1)

Table 1. Distribution of socio-educational and religious-spiritual variables among health science students.

n=sample; %=Relative frequency; SD=Standard deviation.

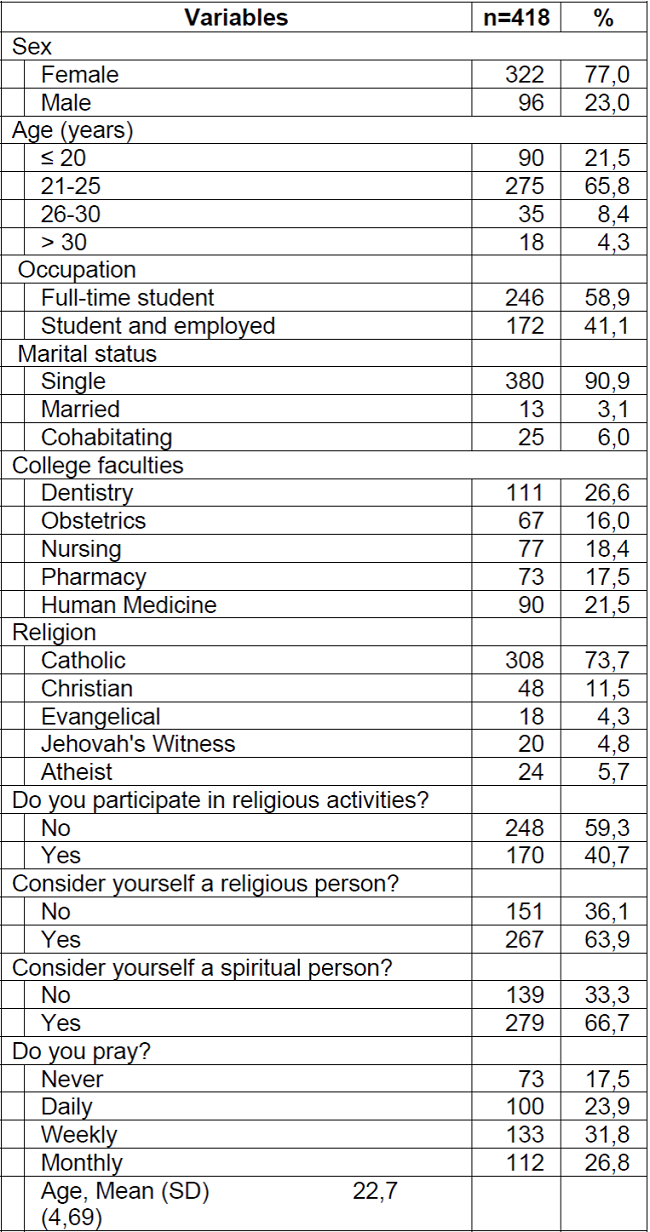

The healthy profile of Spiritual Intelligence (SI) was reported by 21.1% of health science students, with higher proportions found among students who study and work simultaneously (27.9%), married individuals (76.9%), Jehovah's Witnesses (50%), those who participate in religious activities (31.2%), consider themselves religious (24.7%), consider themselves spiritual (29.4%), and practice daily (42.0%) or weekly (24.8%) prayer, respectively. These differences were statistically significant (p<0.05). Additionally, among female students (21.9%), obstetrics students (34.3%), and those over 30 years of age, the differences were not statistically significant (p>0.05). (Table 2)

Table 2. Descriptive and bivariate analysis of socio-educational and religious-spiritual variables according to the healthy profile of Spiritual Intelligence.

n=Sample; %=Relative frequency; CI95%=95% Confidence Intervals; *Chi-square tests for frequency distribution and proportion difference.

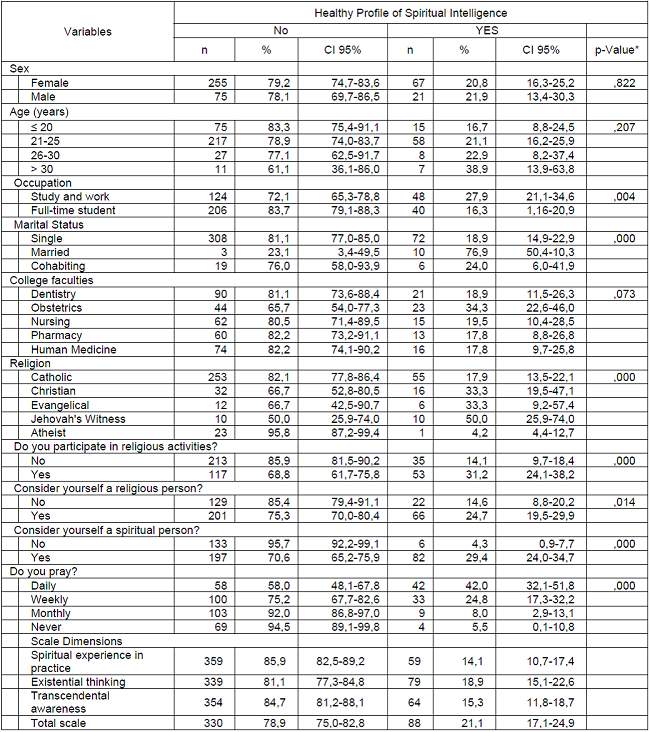

Due to the significant differences found in certain variables, an adjustment was performed using generalized linear models. In the adjusted regression model, considering oneself a spiritual person (aPR = 4.77; 95% CI: 1.98-11.4) and practicing daily prayer (aPR = 3.02; 95% CI: 1.54-5.92) and weekly prayer (aPR = 2.30; 95% CI: 1.12-4.72) were associated with a higher healthy profile of Spiritual Intelligence. However, being over 30 years of age, studying and working simultaneously, being single or married respectively, being an obstetrics student, having Catholic, Christian, or Jehovah's Witness religion, participating in religious activities, and considering oneself a religious person showed an unadjusted association with the healthy profile of Spiritual Intelligence. (Table 3)

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to understand the profile of IE and its associated factors in students of Health Sciences (HSS) in the fields of nursing, medicine, dentistry, obstetrics, and pharmacy at a public university in Peru. The findings from the studied sample revealed that two out of ten university students have a healthy SI profile, while a high proportion (78.9%) showed an unhealthy profile. Similar results have been reported by other researchers (11,17,18,19)), who found low, moderate, or unhealthy levels of SI with significant inverse correlations with variables such as perceived stress, academic achievement, depression, anxiety, and work stress in university students studying HS and other disciplines. These findings are concerning as SI is associated with the socio-humanistic competence required by these students (20). To achieve socio-humanistic competence, it is necessary to promote the development of SI as a cross-cutting strategy in health professional education (19)-,21). SI connects a student's mental and spiritual life with their performance and functioning, influencing psychological variables that can be improved in students (22). Additionally, SI can impact nursing students' competence in providing spiritual care to patients. Therefore, appropriate plans are recommended to promote SI and increase levels of critical thinking and spiritual self-awareness (23).

The unhealthy or inadequate profile of SI was predominantly observed in the dimension of "spiritual experience in practice" (85.9%). This indicates that students have deficiencies related to their own principles, student or pre-professional practice, sacred duty, professional service and vocation, belief in a higher divinity, and life mission. These findings are consistent with a study conducted in the region (1) and may reflect the dystopian society of today. In this regard, Gonzales et al. (24) found a lack of presence of values such as respect, solidarity, tolerance, cooperation, and justice, which are benefits generated by SI, as well as primary values like honesty, responsibility, and coexistence.

In this study, a higher proportion of students with an adequate SI profile was found among those who study and work simultaneously, are married, belong to the Jehovah's Witness religion, participate in religious activities, consider themselves religious and spiritual, and engage in daily and weekly prayer. These findings are similar to those of a Peruvian study (1). However, they differ in reporting higher SI scores among older adults aged 60 years and above, divorced individuals, and those with an evangelical religious affiliation. These discrepancies could be explained by the differences in the average age of participants between the two samples. The reported statistical differences may be attributed to various factors that influence spiritual intelligence and contribute to its development, such as age (25), spiritual experiences in life (26), and spiritual therapies (27).

Furthermore, a statistically significant association was found between an adequate SI profile and the variables "participates in religious activities," "considers themselves religious," "considers themselves spiritual," and "engages in daily prayer." These findings align with the results of another recent local study (1), indicating that these factors influence the level of SI as shown in the literature concerning spiritual variables (28). Possessing SI contributes to professional practice and workplace competencies and has been found to be beneficial for nurses and nursing students (29). It also enhances the clinical competence of students, especially in the fields of medicine and nursing, among others (30), and improves empathy and mental health. Therefore, it is suggested to incorporate and develop this modality of intelligence in training programs and governmental decisions (31). Additionally, it is effective in enhancing the communication skills of nurses (32).

As limitations of the research, it should be noted that there are few studies that quantify the variable studied in a population of HSS, which made comparisons difficult. Moreover, a cause-and-effect relationship was not established. However, describing, comparing, and associating the analyzed variables is pertinent and necessary, as it allows for the detection and intervention of specific findings in the analyzed groups. Consequently, further research is needed, including explanatory variables mainly related to unhealthy or inadequate SI. Nonetheless, the study is important as it provides an approach to the ninth multiple intelligence in HSS.

REFERENCES

1. Becerra-Canales B, Becerra-Huamán D. Inteligencia Consciencial en adultos peruanos en tiempos de pandemia por COVID-19. Revista Cubana de Enfermería [Internet]. 2021 [citado 03 feb 2023]; 37(1): 37:e4117 Disponible en: http://revenfermeria.sld.cu/index.php/enf/article/view/4117 [ Links ]

2. Parra A, Ribilla N. Relación entre inteligencia espiritual y satisfacción existencial con la experiencia paranormal. Persona. 2020; 23(2): 101-116. Doi: https://doi.org/10.26439/persona2020.n023(2).4854 [ Links ]

3. Fidelis A, Formiga N, Fernandes A. Inteligência espiritual e reajuste do trabalho em brasileiros e portugueses de Unidades Hospitalares. RECIMA21-Revista Científica Multidisciplinar. 2022; 3(4): e341382-e341382. Doi: https://doi.org/10.47820/recima21.v3i4.1382 [ Links ]

4. Hyde B. The plausibility of spiritual intelligence: spiritual experience, problem solving and neural sites. International Journal of Children's Spirituality. 2004; 9(1):39-52. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1364436042000200816 [ Links ]

5. Mayer J. Spiritual Intelligence or Spiritual Consciousness? The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 2000; 10(1):47-56. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327582IJPR1001 [ Links ]

6. Bustelo-Gracia J. La percepción de la inteligencia espiritual en las empresas. Revista Empresa y Humanismo. 2019; 22(2): 9-25. Doi: https://doi.org/10.15581/015.XXII.2.9-25 [ Links ]

7. Srivastava P. Spiritual intelligence: An overview. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development. 2016; 3(3): 224-27. Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321875385 [ Links ]

8. Rodríguez T. Inteligencia espiritual. Sapiens, 2013 [citado 03 feb 2023]; 14(1):13-22. Disponible en: https://ve.scielo.org/scielo.php?pid=S1317-58152013000100002&script=sci_arttext [ Links ]

9. Conti R. del C. La educación de la inteligencia espiritual en jóvenes del tercer ciclo del colegio Inmaculada Concepción de ciudad del Este. Revista Científica Estudios E Investigaciones. 2019; 8(1):36-49. Doi: https://doi.org/10.26885/rcei.8.1.36 [ Links ]

10. Caraballo M. del R. La inteligencia espiritual: un desafío para la Educación Inclusiva Ecosófica. Sinergias Educativas. 2019; 4(2):17-42. Doi: https://doi.org/10.37954/se.v4i2.38 [ Links ]

11. Borja N, Gómez P. Inteligencia espiritual y logro de aprendizajes en estudiantes de educación superior tecnológica. Llimpi. 2022; 1(1): 1-7. Doi: https://doi.org/10.54943/llimpi.v1i1.18 [ Links ]

12. Piñeros A. Formación humanística del estudiante universitario. Studiositas. 2009; 4(3): 9-20. Disponible en: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3658899 [ Links ]

13. García D, Díaz R, Mendoza M. Los proyectos artísticos en la formación humanística de los estudiantes de medicina. MEDISAN [Internet]. 2018 [citado 2023 Mar 08]; 22(4): 460-464. Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1029-30192018000400016&lng=es [ Links ]

14. Domínguez H, Calva J. Educación humanista, liberadora y emancipatoria para salvar a la humanidad realizándola. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos. 2022; 52(3): 7-14. Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=27071219024 [ Links ]

15. Becerra-Canales B, Becerra-Huamán D. Diseño y validación de la escala de Inteligencia Espiritual en la práctica sanitaria, Ica-Perú. Enfermería Global. 2020; 19 (4): 349-378. DOI: https://doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.417371. [ Links ]

16. Becerra-Canales B, Campos-Martínez H, Campos-Sobrino M, et al. Trastorno de estrés postraumático y calidad de vida del paciente post-COVID-19 en Atención Primaria. Aten Primaria. 2022; 54(10):102460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aprim.2022.102460 [ Links ]

17. Shahrokhi A, Elikaei N, Yekefallah L, Barikani A. Relación entre la inteligencia espiritual y el estrés percibido entre enfermeras de cuidados críticos. Revista de enfermedades inflamatorias. 2018; 22(3):40-49 Url: http://journal.qums.ac.ir/article-1-2493-en.html [ Links ]

18. Barraza-López R, Muñoz-Navarro N, Behrens-Pérez C. Relación entre inteligencia emocional y depresión-ansiedad y estrés en estudiantes de medicina de primer año. Rev Chil Neuro-Psiquiat. 2017; 55(1): 18-25. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-92272017000100003 [ Links ]

19. Sumarriva L, Chávez N. Relación entre inteligencia espiritual y estrés percibido en estudiantes de pregrado: estudio preliminar. Rev Peru Med Integrativa. 2017;2(4):841-45. Disponible en: http://rpmi.pe/index.php/rpmi/article/view/605 [ Links ]

20. Jay FR, Duharte DR, Utria YA, Estevez YA, Acosta MEG. El desarrollo sociohumanista de los profesionales de la Salud. Rev Hum Med. 2018; 18(1):20-34. Disponible en: https://www.medigraphic.com/cgi-bin/new/resumen.cgi?IDARTICULO=79936 [ Links ]

21. Quiliano-Navarro M, Quiliano-Navarro M. Inteligencia emocional y estrés académico en estudiantes de enfermería. Cienc. enferm. [Internet]. 2020 [citado 03 feb 2023]; 26:3. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/s0717-95532020000100203 [ Links ]

22. Ma Q, Wang F. The Role of Students' Spiritual Intelligence in Enhancing Their Academic Engagement: A Theoretical Review. Front Psychol. 2022;13:857842. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.857842 [ Links ]

23. Ahmadi M, Estebsari F, Poormansouri S, Jahani S, Sedighie L. Perceived professional competence in spiritual care and predictive role of spiritual intelligence in Iranian nursing students. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;57:103227. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103227 [ Links ]

24. Gonzales C, Vera L. Inteligencia Espiritual y Valores Personales en los integrantes de la Coordinación del Proyecto Educativo Regional. Revista EDUCARE. 2014 [acceso: 12/03/2023]; 18(1): 50-77. Disponible en: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5163441 [ Links ]

25. King D, DeCicco T. A viable model and self-report measure of spiritual intelligence. The International Journal of Transpersonal Studies. 2009 [acceso: 14/03/2023]; 28: 68-85. Disponible en: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies/vol28/iss1/8/ [ Links ]

26. Vaughan F. What is Spiritual Intelligence. J Humanist Psychol. 2002 [acceso: 15/03/2023]; 42(2):16-33. Recuperado de: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/fa5c/5e6d51662d3b55e0ede528189cd3c60e489b.pdf [ Links ]

27. Santacruz F, Miyashiro E, Morales L, Pazos P, Villena V, Tipán E, et al. Reactivación de las competencias de la inteligencia espiritual en pacientes con alcohol y fármaco-dependencia. VI Encuentro Latinoamericano de Metodología de las Ciencias Sociales (ELMeCS) Innovación y creatividad en la investigación social: Navegando la compleja realidad latinoamericana. Ecuador: Universidad de Cuenca; del 7 al 9 Nov. 2018. [acceso: 28/03/2023]. Disponible en: http://elmecs.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/vielmecs/actas/Santacruz.pdf [ Links ]

28. González-Rivera J, Quintero-Jiménez N, Veray-Alicea J, Rosario-Rodríguez A. Adaptación y validación de la escala de espiritualidad de Delaney en una muestra de adultos puertorriqueños. Revista Electrónica de Psicología Iztacala. 2017 [acceso: 18/03/2023]; 20(1): 296-320. Disponible en: http://www.revistas.unam.mx/index.php/repi/article/view/58935 [ Links ]

29. Sharifnia AM, Fernandez R, Green H, Alananzeh I. The effectiveness of spiritual intelligence educational interventions for nurses and nursing students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ Pract. 2022;63:103380. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103380 [ Links ]

30. Imani B, Imani G, Karampourian A. Correlation between Spiritual Intelligence and Clinical Competency in Students Who Are Children of War Victims. Iran J Psychiatry. 2021;16(3):329-335. doi: 10.18502/ijps.v16i3.6259. [ Links ]

31. Aliabadi PK, Zazoly AZ, Sohrab M, Neyestani F, Nazari N, Mousavi SH, Fallah A, Youneszadeh M, Ghasemiyan M, Ferdowsi M. The role of spiritual intelligence in predicting the empathy levels of nurses with COVID-19 patients. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2021;35(6):658-663. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2021.10.007 [ Links ]

32. Arad M, Alilu L, Habibzadeh H, Khalkhali H, Goli R. Effect of spiritual intelligence training on nurses' skills for communicating with patients - an experimental study. J Educ Health Promot. 2022;11:127. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_1483_20 [ Links ]

Received: April 13, 2023; Accepted: May 20, 2023

texto en

texto en