Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Enfermería Global

versión On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.23 no.73 Murcia ene. 2024 Epub 23-Feb-2024

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.563831

Originals

Stigma and mental health in patients with a cancer diagnosis

1César Vallejo University. Trujillo, Peru

2Autonomous University of Peru. Lima, Peru

Objective:

To determine the relationship between stigma and mental health in patients diagnosed with cancer.

Material and Methods:

Correlational study with a non-probabilistic sample of 250 patients diagnosed with cancer, between 26 and 72 years of age (85.2% women and 14.8% men). Data collection was carried out in a private health center using the Perceived, Experienced and Internalized Stigma Questionnaire, the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4), and a sociodemographic characteristics form. Data analysis was performed using Pearson's correlation coefficient, and the magnitude of the effects was analyzed using the Gignac and Szodorai criteria.

Results:

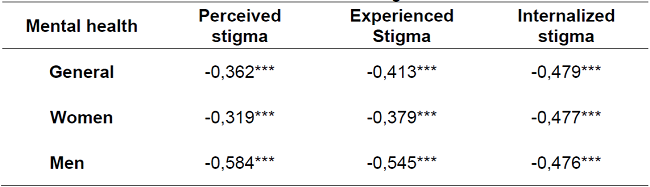

Large effect inverse associations were identified between mental health and perceived stigma (r = -0.362), experienced stigma (r = -0.413) and internalized stigma (r = -0.479).

Conclusions:

The results support that the higher the perceived, experienced, and internalized stigma, the lower the mental health scores of patients with a cancer diagnosis.

Keywords: Social stigma; Mental health; Cancer

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is a serious and prevalent disease. In 2020, 19.3 million new cases were estimated and it was responsible for 10 million deaths (1). Beyond the physical affectation, cancer generates a relevant impact on the emotional world of the subject(2). The tendency to experience shame, guilt (3), anxiety and depression (4) constantly accompany the diagnosis. In addition, negative and discriminatory attitudes towards patients diagnosed with cancer are common (5).

Cancer is often perceived as a stigma in many societies, which is related to fear of the disease and mortality rates. Cancer stigma is found with an estimated prevalence of 61.2% (6). It has been identified that in addition to patients, 75% of caregivers claimed to have experienced the stigma. However, caregivers were also found to hold stigmatizing beliefs and attitudes towards their sufferers (7). In cancer stigma, the patient has the perception that they are less socially accepted, and that others are prejudiced against them because of their diagnosis (4).

The perception of stigmatization, on the part of patients diagnosed with cancer, is associated with the prevention of seeking specialized care and abandonment of treatment (8). As well as refusing to undergo screening tests recommended to prevent it (9).

Social stigma is marked by stereotypes and discrimination that can affect minority groups, placing them under some label that excludes them (10). The experience of discrimination is an important stress factor that results in poor mental health (11). When the subject is stigmatized they are stripped of their social status and included within the stereotype, isolating them from others (12).

Cancer stigma has been identified as a major source of psychological distress (13), and is associated with negative psychological states such as depression and anxiety, decreased self-esteem and self-efficacy (14), and poor quality of life (12). In addition, cancer stigma was identified as being associated with loss of body image, self-blame, intrusive thoughts and social restriction (15). Likewise, higher stigma scores were identified in patients with health, work, family and financial concerns (16).

Although the problem posed by cancer stigma has not been thoroughly studied, any stigmatization has been shown to negatively influence a patient's living condition (17) and lower emotional well-being (18).

In recent years, there has been an increase in scientific production regarding cancer stigma. However, the experience of stigma in comprehensive cancer care is rarely addressed. In this sense, this study aims to determine the relationship between cancer stigma and mental health in cancer patients. Elucidating such association will contribute as evidence for the design of interventions for oncology patients in order to improve their quality of life and favor their psychological well-being.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

Design and participants

The cross-sectional study with correlational design, had a sample of 250 people diagnosed with cancer, who attended a private health center in the province of Trujillo - Peru. They were chosen by means of an accidental non-probabilistic sampling, according to the following inclusion criteria: (a) that they were aware of their diagnosis, and (b) that they gave their informed consent. Patients diagnosed with other diseases were excluded.

Procedure

Data collection was carried out between August and November 2022. The instruments were administered face-to-face in an oncology clinic, where permission was previously requested to approach the patients. The evaluators provided information on the objective of the study and on the confidentiality of the data. Their voluntary participation was requested and expressed by signing the informed consent form.

Variables and Measurement

The Perceived, Experienced and Internalized Stigma Questionnaire, developed in India, was used to measure cancer stigma (7). The scale has 21 items organized in 3 dimensions, with 4 response options (Strongly Disagree=0, to Strongly Agree=3). It is aimed at measuring stigma in adult oncology patients. For the purposes of this study, the scale was translated from English into Spanish. The translation was carried out by two professionals: a certified professional interpreter and a medical oncologist fluent in English. A comparison was made of the items translated by each expert; both translations were the same; therefore, the translated version remained unchanged. This version of the instrument was applied to a pilot sample of 10 oncology patients to evaluate the clarity of the items; it was then applied to the selected sample. The factor analysis confirmed the 3-factor structure (CFI = 0.902, TLI = 0.886, RMSEA = 0.069) with six correlated errors (6 - 7/15 -16/18 -19/1 - 2/9 -11/11 - 12). Regarding internal consistency, adequate indexes were identified in the overall scale (α Cronbach = 0.89) and in the dimensions (α Cronbach > 0.70).

As for mental health, it was measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4), developed in the United States (19). It is a unidimensional scale of 4 items, with 4 response options (Never=0 to most of the time=3), measuring psychological distress (anxiety and depression) in adults. In the original study, 2 discrete factors (depression and anxiety) were identified that explained 84% of the total variance and adequate internal consistency (α Cronbach = 0.80). In the present study, the internal structure of the instrument was analyzed by confirmatory factor analysis, resulting in an adequate fit of the unifactor model (CFI = 0.96 TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.04) with a correlated error (1-2). Likewise, the internal consistency was favorable (α Cronbach = 0.81).

Data analysis

First, the distribution of the data was identified by means of asymmetry and kurtosis; values between +/- 1.5 indicated a normal distribution. Based on this, Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to determine the relationships among variables. The interpretation of the strength of the relationship was analyzed using the criteria of Gignac and Szodorai (< 0.10 trivial, ≥ 0.20 moderate, ≥ 0.30 large) (20).

Ethical aspects

The study complied with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad César Vallejo. Institutional authorization was obtained from the health center and informed consent was requested from the participants. Each participant was informed of their rights, the confidentiality of the information provided, and the voluntary nature of their participation.

RESULTS

The sample consisted of 250 adults between 26 and 72 years of age. Of the total, 213 were women (85.2%) and 37 were men (14.8%). Of these, 52.4% were diagnosed with cervical cancer, 17.6% with breast cancer, and 30.0% with other types of cancer. In addition, 15.2% had undifferentiated diagnosis, in 25.2% the cancer was degree 1, in 19.2% degree 2, in 18.8% degree 3 and in 21.6% degree 4.

Table 1 shows that mental health obtained inverse correlates with perceived stigma (r = -0.362), experienced stigma (r = -0.413) and internalized stigma (r = -0.479). All relationships found were large effect (r ≥0.30). Likewise, when associations are identified differentiating by gender, large correlates (r ≥0.30) were identified in both women and men, with higher correlation coefficients in perceived stigma and experienced stigma in men.

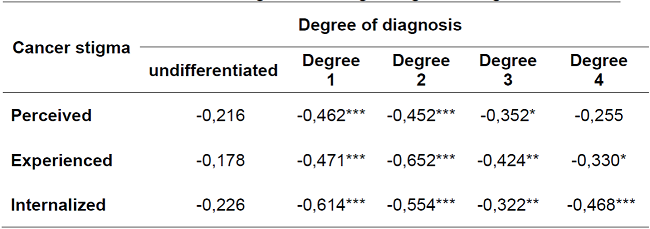

Cancer stigma and its dimensions obtained large correlations (r ≥0.30) with all diagnostic degrees, except undifferentiated degree, with which associations were moderate (r ≥ 0.20) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Social stigma regarding the disease can have a negative impact on the mental health of cancer patients. In this sense, a study was conducted in 250 people diagnosed with cancer with the purpose of determining the relationship between cancer stigma and mental health.

It was found that cancer stigma is associated in all its dimensions with mental health; specifically, it was identified that the greater the perception of stigma, the lower the patient's mental health. These results are consistent with previous studies (12,13,14,15). Stigma refers to a characteristic that implies a broad devaluation of the person who suffers from it (21). Perceived stigma occurs when the person is aware of the negative appraisals he/she receives from others towards him/her (7). Stigmatizing attitudes limit the patient to talk about their diagnosis, which leads to mental health problems and makes them less efficient in decision making and decreases the possibility of successful adherence to treatment (22).

Patients experience cancer stigma through the reactions and behaviors of prejudice and discrimination from the environment (7)). This experience leads to poorer mental health. The importance of the emotional aspect of cancer care should be taken into account. Most cancer patients feel sadness, anxiety and fear, which can be favored by the stigma and result in physical deterioration and lower treatment efficacy (23).

When the patient accepts the negative evaluation of others regarding his condition, we speak of internalized stigma (7). Sometimes people diagnosed with cancer are stigmatized because of their physical appearance (24) and this leads to a significant negative impact on self-esteem and self-image. Patients may perceive themselves as different from others, thus validating the stigma that excludes them and internalizing it. Perceived and experienced cancer stigma is related to mental health, more strongly in men than in women. It is likely that the changes generated by the disease in men's mental health are also associated with decreased work activity. Some studies have found that unemployment significantly affects mental health, especially in men (25). It could also be due to the fact that women regulate their fears better than men (26). This information is of interest and should be taken into account because men are the ones who seek less attention for mental health problems (27) and could be more affected by this problem, without receiving the necessary help, which further aggravates the mental health problem.

Stigma is equally present at all levels of cancer diagnosis. Regardless of the stage of the disease, whoever is diagnosed is vulnerable to depression (28), because together with the diagnosis, patients may be stigmatized because they are believed to be ineffective and inactive. This has repercussions on their self-image, diminishing their psychological well-being (24).

The relationship between cancer stigma and mental health tends to weaken as the severity of the disease increases. It is possibly linked to the non-acceptance of the disease, with the lack of knowledge and uncertainty generated by its development, especially in the early stages of the disease (29). However, the relationship is less when the diagnosis is unclear or imprecise, in that sense, patients may enter a stage of denial of the disease, so as not to feel affected in their mental health (30).

These findings have practical implications for integral cancer care. Interventions should consider a holistic approach to cancer patient care, taking into account the physical, emotional and social state of the patient. Given that stigma has a negative impact on the patient, health professionals have the task of orienting their actions to meet the needs of people with cancer. Encouraging open and respectful dialogue creates an environment that validates their emotions, raises awareness and can correct preconceived ideas about cancer. The main focus of the actions taken should be to provide emotional, social and practical support to the oncology patient.

The limitations of the study are the type of sampling used, which could affect external validity. Therefore, care should be taken with the generalization of the results. Similarly, the cross-sectional design does not allow us to identify the causal nature of the associations, which would be achieved with a longitudinal study, which could be undertaken in subsequent studies. In addition, it is recommended that future studies consider the psychological phases of the oncologic process, since mental health problems could be exacerbated in the denial stage. Likewise, to provide the necessary attention considering gender.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, it was identified that cancer stigma is strongly associated with mental health in cancer patients. Cancer patients are subject to adverse reactions from society, leading to poorer mental health outcomes. Consequently, health professionals, in their approach, should pay attention to the identified associations and consider measures to intervene on cancer stigma and promote psychological well-being.

REFERENCIAS

1. The Global Cancer Observatory. Estimated number of new cases in 2020, worldwide, both sexes, all ages [Internet]. 2022 [citado 02 Feb 2023]. Disponible en: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/online-analysis-pie?v=2020&mode=cancer&mode_population=continents&population=900&populations=900&key=total&sex=0&cancer=39&type=0&statistic=5&prevalence=0&population_group=0&ages_group%5B%5D=0&ages_group%5B%5D=17&nb_items=7&group_cancer=1&include_nmsc=1&include_nmsc_other=1&half_pie=0&donut=0 [ Links ]

2. Park G, Kim J. Depressive symptoms among cancer patients: Variation by gender, cancer type, and social engagement. Res. Nurs. Health. 2021; 44(5): 811-21. Doi: 10.1002/nur.22168 [ Links ]

3. Williamson T, Ostroff J, Haque N, Martin C, Hamann H, Banerjee S, Shen M. Dispositional shame and guilt as predictors of depressive symptoms and anxiety among adults with lung cancer: The mediational role of internalized stigma. Stigma health. 2020; 5(4): 425-33. Doi: 10.1037/sah0000214 [ Links ]

4. Teo I, Ozdemir S, Malhotra C, Meijuan G, Ocampo R, Bhatnagar S, et al. High anxiety and depression scores and mental health service use among South Asian advanced cancer patients: A multi-country study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021; 62(5), 997-1007. Doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.04.005 [ Links ]

5. Yilmaz M, Dissiz G, Usluoglu A, Iriz S, Demir F, Alacacioglu A. Cancer-Related Stigma and Depression in Cancer Patients in A Middle-Income Country. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020; 7(1): 95-102. Doi: 10.4103/apjon.apjon_45_19 [ Links ]

6. Fujisawa D, Umezawa S, Fujimori M, Miyashita M. Prevalence and associated factors of perceived cancer-related stigma in Japanese cancer survivors. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020; 50(11): 1325-29. Doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyaa135 [ Links ]

7. Squiers L, Siddiqui M, Kataria I, Dhillon P, Aggarwal A, Bann C, et al. Perceived, Experienced, and Internalized Cancer Stigma: Perspectives of Cancer Patients and Caregivers in India. RTI Press. 2021. Doi: 10.3768/rtipress.2021.rr.0044.2104 [ Links ]

8. Borges G. Current status of violence, suicide, alcohol use, and stigma in Mexico. Salud mental. 2021; 44(2): 41-2. Doi: 10.17711/sm.0185-3325.2021.007 [ Links ]

9. Vrinten C, Gallagher A, Waller J, Marlow L. Cancer stigma and cancer screening attendance: a population based survey in England. BMC Cancer. 2019; 19(566). Doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5787-x [ Links ]

10. López C, López A, Arbesú ME. Evolución del estigma hacia salud mental en especialistas sanitarios en formación en Asturias. Enfermería Global. 2023; 22(1): 105-33. Doi: 10.6018/eglobal.525701 [ Links ]

11. Fujisawa D, Hagiwara N. Cancer Stigma and its Health Consequences. Curr. Breast Cancer Rep. 2015; 7(3): 143-50. Doi: 10.1007/s12609-015-0185-0 [ Links ]

12. Zhang Y, Cui C, Wang Y, Wang L. Effects of stigma, hope and social support on quality of life among Chinese patients diagnosed with oral cancer: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2020; 18(112). Doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01353-9 [ Links ]

13. Amini-Tehrani M, Zamanian H, Daryaafzoon M, Andikolaei S, Mohebbi M, Imani A, et al. Body image, internalized stigma and enacted stigma predict psychological distress in women with breast cancer: A serial mediation model. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021; 77(8): 3412-23. Doi: 10.1111/jan.14881 [ Links ]

14. Sing S, Syurina E, Peters R, Ika A, Zweekhorst M. Non-Communicable Diseases-Related Stigma: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020; 17(18): 6657. Doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186657 [ Links ]

15. Huang Z, Yu T, Wu S, Hu A. Correlates of stigma for patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support. Cancer. Ther. 2020; 29: 1195-1203. Doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05780-8 [ Links ]

16. Tseng W, Lee Y, Hung C, Lin P, Chien C, Chuang H, et al. Stigma, depression, and anxiety among patients with head and neck cancer. Support. Care Cancer. 2022; 30: 1529-37. Doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06550-w [ Links ]

17. Daryaafzoon M, Amini-Tehrani M, Zohrevandi Z, Hamzehlouiyan M, Ghotbi A, Zarrabi-Ajami S, Zamanian H. Translation and Factor Analysis of the Stigma Scale for Chronic Illnesses 8-Item Version among Iranian Women with Breast Cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2020; 21(2): 449-55. Doi: 10.31557%2FAPJCP.2020.21.2.449 [ Links ]

18. Pang N, Lee J, Pham N, Phan T, Tran K, Dang H, et al. The prevalence of perceived stigma and self-blame and their associations with depression, emotional well-being and social well-being among advanced cancer patients: evidence from the APPROACH cross-sectional study in Vietnam. BMC Palliat. Care. 2021; 20(104). Doi: 10.1186/s12904-021-00803-5 [ Links ]

19. Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams J, Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009; 50(6): 613-21. Doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613 [ Links ]

20. Gignac G, Szodorai E. Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Pers, Individ. Differ. 2016; 102: 74-8. Doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.069 [ Links ]

21. Miric M, Álvaro J, González R, Rosas A. Microsociología del estigma: aportes de Erving Goffman a la conceptualización psicosociológica del estigma social. Psicologia e Saber Social. 2017; 6(2): 172-85. Doi: 10.12957/psi.saber.soc.2017.33552 [ Links ]

22. Hernández M, Cruzado A, Prado C, Rodríguez E, Hernández C, González M, Martín J. Salud mental y malestar emocional en pacientes oncológicos. Psicooncología. 2012; 9(2-3): 233-57. Doi: 10.5209/rev_PSIC.2013.v9.n2-3.40895 [ Links ]

23. Suarez V, López O. La dimensión emocional en torno al cáncer. Estrategias de análisis desde la antropología de la salud. Revista de Ciencias Antropológicas. 2019; 26(76): 31-60. Disponible en: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2448-84882019000300031 [ Links ]

24. Penagos J, Pintado S. Evaluación del estigma hacia pacientes con cáncer: una aproximación psicométrica. Psicología y Salud. 2020; 30(2): 153-60. Doi: 10.25009/pys.v30i2.2650 [ Links ]

25. Ramos-Lira L. ¿Por qué hablar de género y salud mental? Salud Ment. 2014; 37(4):275-81. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0185-33252014000400001&lng=es [ Links ]

26. Mejía C, Rodríguez-Alarcón J, Garay-Rios L, Enriquez-Anco M, Moreno A, Haytán-Rojas K, et al. Percepción de miedo o exageración que transmiten los medios de comunicación en la población peruana durante la pandemia de la COVID-19. Rev. Cubana Inv. Beiméd. 2020; 39(2): e698. Disponible en: https://revibiomedica.sld.cu/index.php/ibi/article/view/698 [ Links ]

27. Sagar-Ouriaghli I, Godfrey E, Bridge L, Meade L, Brown J. Improving Mental Health Service Utilization Among Men: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Behavior Change Techniques Within Interventions Targeting Help-Seeking. Am. J. Mens. Health. 2019; 13(3). Doi: 10.1177%2F1557988319857009 [ Links ]

28. Diz R, Garza A, Olivas E, Montes J, Fernández G. Cáncer y depresión. Una revisión. Psicología y Salud. 2019; 29(1): 115-24. Doi: 10.25009/pys.v29i1.2573 [ Links ]

29. Secinti E, Tometich D, Johns S, Mosher C. The relationship between acceptance of cancer and distress: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019; 71: 27-38. Doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2019.05.001 [ Links ]

30. Páramo-Rodríguez L, Cavero-Carbonell C, Guardiola-Vilarroig S, López-Maside A, González-Sanjuán E, Zurriaga O. Demora diagnóstica en enfermedades raras: entre el miedo y la resiliencia. Gac. Sanit. 2023; 37: 102272. Doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2022.102272 [ Links ]

Received: April 03, 2023; Accepted: July 08, 2023

texto en

texto en