Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Clínica de Medicina de Familia

versión On-line ISSN 2386-8201versión impresa ISSN 1699-695X

Rev Clin Med Fam vol.17 no.1 Barcelona feb. 2024 Epub 18-Mar-2024

https://dx.doi.org/10.55783/rcmf.170107

ARTÍCULO ESPECIAL

Executive summary of the consensus document on the shared care of patients with HIV infection between primary and hospital carei,ii

aServicio de Enfermedades Infecciosas. Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal. IRYCIS. Madrid (España)

bUnidad de Enfermedades Infecciosas. Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón. Alcorcón. Madrid (España)

cCentro de Salud Segorbe. Castellón (España)

dCentro de Información y Prevención del Sida y otras ITS. Valencia (España)

eCentro de Salud La Florida Sud. Institut Català de la Salut. L'Hospitalet de Llobregat. Barcelona (España)

The current reality of the diagnosis and treatment of HIV infection justifies a multidisciplinary and coordinated approach between primary care and hospital care. This entails a two-way relationship and communication between the two care settings. This consensus document, coordinated by the AIDS Study Group of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC-GeSIDA) and the Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine (semFYC), arose because of this need. Here, the recommendations of the four blocks that comprise it are summarized: the first tackles aspects of prevention and diagnosis of HIV infection; the second contemplates the clinical care and management of people living with HIV; the third deals with social aspects, including legal and confidentiality issues, quality of life, and the role of NGOs; finally, the fourth block addresses two-way and shared training/teaching and research.

Keywords: HIV; Primary Care; Hospital Care; Shared Care

1. BACKGROUND

This consensus document, coordinated by the AIDS Study Group of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC-GeSIDA) and the Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine (semFYC), arises from the need to pool knowledge and evidence to improve the multidisciplinary and coordinated approach between Primary Care (PC) and Hospital Care (HC), both in the prevention and screening of HIV infection in the general population, and in the comprehensive care of the multiple aspects and nuances that make up the care of people living with HIV (PLHIV)1.

The recommendations of the four blocks, which contemplate bidirectionality and communication between the two care settings, are summarized here. Some recommendations may have been updated after the publication of the original consensus document; the clinical guidelines published periodically by GeSIDA should be consulted.

2. PREVENTION, DIAGNOSIS, AND REFERRAL

2.1. Prevention of HIV infection

The starting point for preventing HIV infection is identifying the risk of acquisition to apply the most appropriate prevention measures for each individual (A-II).

How can we improve risk identification?

We need to raise awareness about screening guidelines that identify persons at increased risk of acquiring HIV infection (A-II).

Patient medical histories should include the number of sexual partners, types of practices, condom use, drug use during sexual intercourse, sharing of drug-related material during consumption, history of other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), psychosocial situation, and country of origin. Staff should be given sufficient time to attend to each patient according to their needs (B-III).

What are the non-pharmacological prevention measures for HIV and other STIs?

Gynecological prevention and family planning (B-III). Prevention of mother-to-child transmission (A-I).

Male circumcision only in settings with generalized/widespread HIV epidemic (C-II).

Condom use (A-II).

Regular HIV testing in populations at high risk (A-III).

Behavioral modification interventions (informational campaigns, sex education, outreach to vulnerable people, risk reduction...) (B-II).

Social assessment, including socio-familial environment and livelihoods, to provide support measures if necessary (B-II).

Syphilis screening annually if there is unprotected sex (B-II), and in gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) with risk factors, monitoring at least N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis and hepatitis C virus (C-II). Screening should be performed every 3-6 months, depending on risk factors.

What are the pharmacological HIV prevention measures?

Offer antiretroviral treatment (ART) to all PLWH (A-I), according to current recommendations in clinical guidelines2.

Offer pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) (A-I) and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) (A-II) in situations in which they are indicated, following current recommendations3 (table 1 and 2).

Regular screening and early treatment of STIs, since ulcerative and rectal STIs increase the risk of acquiring HIV (B-II).

Table 1 Criteria to identify candidates for pre-exposure prophylaxis approved by the National Health System

|

1. Gay and bisexual men and other men who have sex with HIV-negative men and transexual individuals over 16 years old, with at least two of the following criteria:

More than 10 different sexual partners in the past year Practice of unprotected anal sex in the past year Drug use related to unprotected sex in the past year Administration of post-exposure prophylaxis on several occasions in the past year At least one bacterial STI in the past year |

|---|

| 2. Women engaged in prostitution who report non-regular condom use |

|

3. Cisexual women and men, as well as users of intravenous drugs with unsafe injection practices who report non-regular condom use and who present at least two of the following criteria:

More than 10 different sexual partners in the past year Practice of unprotected anal sex in the past year Drug use related to unprotected sex in the past year Administration of post-exposure prophylaxis on several occasions in the past year At least one bacterial STI in the past year |

|

Remarks:

HIV infection must be ruled out before prescribing PrEP. If there is any doubt about a possible recent infection (mononucleosis syndrome or other criterion), PrEP should not be recommended until reasonably ruling out HIV infection. The patient must be willing to regularly comply with the recommendations and join a follow-up program over time. There must be no clinical or analytical contraindication to receive TDF or FTC. |

FTC: emtricitabine; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; PrEP: pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI: sexually transmitted infection; TDF: tenofovir.

Table 2 Non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis recommendations

| TYPE OF EXPOSURE | TRANSMISSION RISK ACCORDING TO SOURCE | RECOMENDATION |

|---|---|---|

|

Anal or vaginal intercourse, whether receptive or insertive, without a condom or with the misuse of condoms Sharing syringes or needles to inject drugs Percutaneous puncture with exposure to blood or other potentially infectious fluidsa

Human bites with continuity solution (?) on the skin |

Exposures with observable risk of transmission:

|

Recommend post-exposure prophylaxis |

|

Exposures with low or minimal risk of transmission:

HIV positive with undetectable plasma viral load HIV status unknown without risk factors |

Assess individuallye | |

|

Oral-genital intercourse (penis, vagina, anus), whether receptive or insertive, with or without ejaculation, without condom or other barrier method or poor prophylactic use Exposure of other mucosa or of non-intact skin to blood or other potentially infectious fluidsa

|

Exposures with low or minimal risk of transmission:

HIV positive with detectable or unknown plasma viral load HIV status unknown with risk factors HIV status unknown without risk factors |

Assess individuallye |

|

Any other type of exposure with non-infectious fluidsb

Exposures on intact skin. Bites without rupture of the skin or bleeding. Superficial puncture or erosion with abandoned needles or other sharp or cutting objects that have not been in recent contact with blood. Kisses. Mouth-to-mouth resuscitation without lesions on the skin or mucosa. Hugs. Masturbation without breaking the skin |

Exposures with negligible or no risk of transmission:

HIV positive with detectable or undetectable viral plasma load and HIV status unknown with or without risk factors |

Post-exposure prophylaxis not recommended |

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

aBlood, fluids that contain visible blood, semen, vaginal secretions, cerebrospinal fluid, pericardial pleural effusion, peritoneal, peritoneal, synovial, and amniotic fluid, and human milk.

bUrine, feces, saliva, vomit, nasal secretions, tears, sweat, and sputum, if they do not contain visible blood.

cThe greater the viral plasma load, the greater the risk of transmission.

dMen who have sex with men (MSM), intravenous drug users (IDU), sex workers, sexual aggressors, people with a history of incarceration and individuals originally from a country with an HIV prevalence over 1% (Haiti, Bahamas, Jamaica, Belize, Trinidad and Tobago, Estonia, Russia, Thailand, and sub-Saharan Africa).

eIndividually assess each case. In general, it is not recommended to start post-exposure prophylaxis if the source is a person with HIV with a detectable or unknown viral plasma load, or if the HIV status is unknown without risk factors. In the latter case, not carrying out post-exposure prophylaxis may be considered given that the transmission risk is very low.

2.2. Diagnostic delay. Strategies to optimize screening

What do the clinical guidelines recommend?

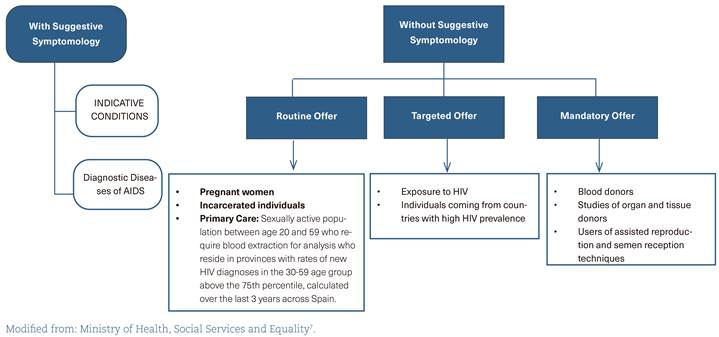

The guidelines propose different screening recommendations, from the routine offer to the general population4 to the targeted offer for people at higher risk5,6.

In Spain, there is a Guide of Recommendations for the Early Diagnosis of HIV in healthcare settings7 (figure 1), which should be updated according to the latest available evidence (A-II).

The training of healthcare professionals on the implications of diagnostic delay should be reinforced so that they request HIV testing more frequently (A-III) (table 3).

Strategies should be implemented to carry out screening in different healthcare settings, providing professionals with the appropriate working conditions in order to perform them (A-II).

Table 3 Indicative conditions and recommendations for the human immunodeficiency virus test

| RISK OF EXPOSURE |

| Persons for whom targeted screening is recommended due to presenting a higher risk of HIV infection |

|

Individuals who request it due to suspecting an exposure to risk Sexual partners of people with HIV infection. Active IDU or individuals with a history of having been IDU and their sexual partners MSM and their sexual partners Individuals who engage in prostitution, as well as their partners and clients in the past year Individuals who want to stop using protection with their stable partners Individuals who have suffered sexual assault Individuals who have had exposure to HIV risk, whether occupational or accidental Individuals originally from countries with a high HIV prevalence (> 1%) and their sexual partners |

| DEFINING CONDITIONS OF AIDS |

| Neoplasms |

|

Cervical cancer Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma Kaposi sarcoma |

| Bacterial infections |

|

Pulmonary or extrapulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis Disseminated or extrapulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex or Mycobacterium kansasii Disseminated or extrapulmonary Mycobacterium, other species or unidentified species Recurrent pneumonia (two or more episodes within 12 months) |

| Viral infections |

|

Cytomegalovirus retinitis Cytomegalovirus in other locations (except liver, spleen, and lymph nodes) Bronchitis/pneumonitis due to herpes simplex, common herpes ulcer(s) > 1 month Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy Herpes simplex: chronic ulcers (> 1 month of duration) or bronchitis, pneumonia or esophagitis |

| Parasitic infections |

|

Cerebral toxoplasmosis Diarrheal cryptosporidiosis > 1 month Isosporiasis > 1 month Atypical disseminated leishmaniasis Reactivation of American Trypanosomiasis (meningoencephalitis or myocarditis) |

| Fungal infections |

|

Pneumocystis pneumonia due to Pneumocystis jirovecii Esophageal Candidiasis Bronchial/tracheal/pulmonary Candidiasis Extrapulmonary cryptococcosis Disseminated/extrapulmonary histoplasmosis Disseminated/extrapulmonary coccidioidomycosis Disseminated talaromycosis |

| INDICATIVE CONDITIONS |

| Conditions associated with undiagnosed HIV prevalence > 0.1% |

|

Sexually transmitted infections Malignant lymphoma Anal cancer/dysplasia Cervical dysplasia Herpes zoster Hepatitis B or C (acute or chronic) Mononucleosis syndrome Leukocytopenia/idiopathic thrombocytopenia that lasts > 4 weeks Seborrheic dermatitis/exanthems Invasive pneumococcal disease Fever with no apparent cause Candidemia Visceral leishmaniasis Pregnancy (implications for the fetus) |

| Conditions possibly associated with undiagnosed HIV prevalence > 0.1% |

|

Primary lung cancer Lymphocytic choriomeningitis Oral hairy leukoplakia Severe or atypical psoriasis Guillain-Barré Syndrome Mononeuritis Subcortical dementia Multiple sclerosis Peripheral neuropathy Unexplained weight loss Idiopathic lymphadenopathy Idiopathic oral candidiasis Idiopathic chronic diarrhea Idiopathic chronic kidney failure Hepatitis A Community-acquired pneumonia Candidiasis Primary lung cancer Lymphocytic choriomeningitis Oral hairy leukoplakia Severe or atypical psoriasis Guillain-Barré Syndrome |

| Conditions with prevalence of HIV infection possibly < 0.1%, but in which not diagnosing the infection can have important negative consequences |

|

Cancer Transplant Autoimmune disease treated with immunosuppressive therapy Primary space-occupying lesion of the brain Idiopathic/thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura |

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; IDU: intravenous drug user; MSM: men who have sex with men.

Modified from: HIV in Europe, HIDES Group. HIV Indicator Conditions: Guidance for Implementing HIV Testing in Adults in Health Care Settings. 20135.

What are the practical experiences in our setting?

In Spain, we have extensive practical experience in strategies to optimize HIV screening, both in healthcare and community settings, including mobile units, pharmacies, premises managed by NGOs, and outreach strategies in high-risk environments with offers in leisure or street venues8-15.

We especially recommend optimizing screening by implementing strategies in PC and community settings (B-I).

2.3. Referral to Hospital Units

Referral for ART is recommended for all patients with HIV infection (A-I) as soon as possible after diagnosis (A-II).

Dynamic communication should be facilitated between primary care specialists and hospitalists to enable patient access in any situation that may require it. Non-face-to-face referrals or e-consultations should be optimized to avoid excesses/mistakes in referrals and to guarantee the rapid exchange of information (A-II).

Rapid two-way inter-consultation circuits should be generated between PC and HC for PLWH presenting STIs, infections not associated with HIV, the need to study a systemic syndrome or for those who cannot go to the hospital and can be attended in PC, as well as displaced patients who need to carry out specific administrative procedures (A-III).

PLWH should be referred to PC if they require care for healthcare matters usually managed by the family physician, keeping the latter at the center of the care of PLWH (A-II).

3. SHARED CARE FOR PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV

3.1. Coordination and Quality of Care

Shared care combines the advantages of PC (proximity and expertise in chronic diseases) with the expertise of an HIV specialist. Although the WHO has recommended shared care since 2004, scarce data are available that evaluate these models in high-income countries, with generally good health outcomes (table 4).

Table 4 Experiences in shared care for individuals who live with human immunodeficiency virus

| MATERIALS AND METHODS | INTERVENTION | PATIENTS INCLUDED | RESULTS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tu D23 | Prospective interventional cohort study | Application of CCM for 18 months | 269 | Improvement in quality indicators, TBC screening, syphilis, pneumococcus vaccine, adherence to ART and undetectable VL |

| Goetz MB24 | Use of Quality Enhancement Research Initiative to improve the diagnosis of HIV infection | Program based on the CCM with clinical reminder alarms, feedback audit, through information systems, organizational changes | NC. 11 centers | 3-5-fold increase in HIV serology requests compared to control centers |

| Gómez Ayerbe C25 | Prospective evaluation of serology request | DRIVE 01 Program Questionnaire on risk exposure and indicative conditions of HIV and HIV screening through rapid tests | 5,329 patients | Increase of HIV screening coverage from 0.96 to 7.17 and in the rate of new diagnoses from 3.1 to 29.6 per 100,000 residents attended |

| Rogers GD26 | Prospective evaluation focused on the use of semistructured interviews and on critical ethnography. |

NO Care and Prevention Program Use and cost of services, quantitative information |

NC |

Improved quality of life, decreased prevalence of depressive symptoms No decrease was observed in the cost of the services |

| Cabral H27 | Randomized pairwise intervention |

Seven educational modules. Monthly telephone contact. Results: follow-up maintained and VL undetectable at 12 months |

348 |

No differences were observed in continuing the follow-up, except in patients with a stable home Undetectable VL in 52% of patients from the intervention group versus 65% in the control group (p: 0.04) |

| Kay ES28 | Review of electronic case histories of a PC clinic for PLWH in the United States. They examine the variables related to irregular follow-up |

NO Number of missed appointments in PC, categorized: 1 - 2 or 3 or more appointments |

1.159 |

Only poverty was predictive for missing three or more appointments (RR: 2.70; CI 95%: 1.49-4.88) Poverty, lack of support, educational level and being younger are associated with missing at least one appointment versus missing no appointments |

| Page J29 | Describe and compare the care of the PLWH seen in PC (10 PCP) and HC (six hospital physicians) in Switzerland |

NO Initial questionnaires, at 6 and 12 months, including questionnaires on depression, physical wellbeing, adherence, quality of life, satisfaction and evaluation of services |

106

45 attended in PC 33 attended in HC 8 in shared care |

Upon finishing the study, no differences were observed in virological follow-up. Patient satisfaction is higher among those attended in PC. No differences were observed with the rest of the health indicators |

| Hutchinson J30 |

Cross-sectional study through questionnaires in clinics that treat PLWH They evaluate factors related with good shared care and barriers to achieving it |

They evaluate the context in which they work, the center's funding, the care provided, coordination with hospital care, knowledge and teaching on HIV of PCP, feasibility and barriers | 10 people reporting |

They observe six shared care models that can be grouped into three categories:

PC model that also provides specialized care in HIV PC model that only offers PC with complementary services PC that offers specialized services to socially at-risk groups |

| Kendal CE31 | Cross-sectional study to understand the organization and composition of clinics that provide care for PLWH in Canada | NO | 17,678 patients seen in 22 clinics: 12 PC (6 exclusively for HIV patients) and 10 HC | Care related with HIV infection and treatment are provided above all in urban areas and by specialists in HIV. Differences were observed in the services offered. More preventive services are offered in PC: cytologies, mental health, needle distribution, care for chronic diseases, care by peers… |

| Webel A32 | Randomized interventional study, adjusted by socio-demographic factors, social situation, comorbidities... | Intervention in nursing and social work to provide early palliative care related to infection by HIV and other chronic diseases. Evaluation of health outcomes: quality of life, symptom burden, coping skills, social isolation, HIV self-management. | 179 participants (71 intervention and 79 control) |

Results at 27 months of follow-up The intervention had a significant effect on three variables. Self-blame was lower in the control group The symptoms of distress and the understanding of the chronic nature of HIV initially decreased in the intervention group, but they increased later No differences were observed in the execution of advance directives or in the number of visits to the emergency department |

| Riera A33 |

Cross-sectional satisfaction questionnaire Prospective study to evaluate an intervention |

Intervention study in Primary Care (PCIS) in HIV patients with good control: one annual visit in the hospital and one in their PCC Evaluation at 2 years of follow-up through VL, adherence to ART, hospitalizations, death, NAE, evaluation of cholesterolemia and tobacco use |

Initial questionnaire 918 patients 93 patients included in the intervention study |

Mean age 50 years, 14.6 years of HIV in follow-up All the patients had undetectable VL and the adherence to ART was 99.4%. No improvement was observed in the decrease of tobacco use 9 patients presented NAE in the form of neoplasm, 5 cardiovascular events and one acute kidney failure |

What are the main recommendations for shared care?

Using all care settings to support early diagnosis, counseling, and shared follow-up of PLWH is recommended (B-III).

Generating evidence on shared care in high-income countries is considered a priority (C-III).

With the increase in age and comorbidities in PLWH, it is necessary to implement effective organizational models in other chronic diseases, which implies improving coordination between HC and PC (A-III).

A chronic and shared care model between PC and HC for PLWH should be implemented as soon as possible, which would greatly benefit both the patient and the healthcare system (B-II) (table 5).

Table 5 Benefits of shared management between Primary Care and Hospital Care for individuals with human immunodeficiency virus

| Improvement in the control of HIV replication |

| Improvement in patient retention and follow-up |

| Improvement in the vaccination program |

| Patient empowerment by facilitating self-care |

| Prevention and treatment of comorbidities |

| Prevention of drug interactions |

| Early screening for tumors, whether or not they are associated with HIV |

| Diagnosis and treatment of fragility |

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

New models of non-face-to-face care and coordination

The national medical societies in Spain have guidelines regarding telemedicine in the management of PLWH16,17.

Models of non-face-to-face care with patients and between HC and PC should be established to achieve greater proximity and accessibility of care (C-III).

Telemedicine should be seen as a complementary support tool to optimize resources and facilitate patient care (C-III).

Progress should be made towards safer and more standardized telemedicine care, and its results on the health of PLWH should be evaluated (C-III).

3.2. Vaccinations for patients with HIV infection

What are the recommendations on the vaccination schedule?

Vaccinate with the same guidelines as the general population. Live attenuated vaccines with CD4+ cell counts < 200 cells/μL (A-I) are contraindicated.

Pneumococcal (A-II), annual influenza (A-II), SARS-CoV-2 (A-II), high-dose HBV (A-I), and postvaccination serological response (B-I), hepatitis A (A-I), human papillomavirus (A-III), and herpes zoster (B-I) vaccines are indicated (table 6).

Serology against the hepatitis A and B viruses should be performed on all patients at the beginning of the study to assess their vaccination status (A-I). In women of childbearing age, rubella serology is recommended for vaccination if IgG is negative (C-III).

The vaccination status and the vaccination record should be reviewed both in PC and in HC (C-III).

Table 6 Vaccination schedule for patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection

| INFECTION | VACCINES AVAILABLE | PATHWAYS |

|---|---|---|

| INACTIVATED VACCINES | ||

| Pneumococcus | 13-Valent Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) | Designed to administer a single dose

If there is no prior vaccination, administer with no restrictions If there is a prior PPV23 vaccination, it can be administered 1 year later |

| 23-Valent Pneumococcal non-conjugated vaccine (PPV23) |

Administer 2 months after PCV13 Possible booster ≥ 5 years later |

|

| Influenza | Tri- or tetravalent (3-4 subtypes of the influenza virus) | Annual seasonal booster (October-November), no restrictions |

| HBV | There is a combined HBV and HAV vaccine |

3 doses (40 µg): 0, 1 and 6 months 4 doses (20 µg): 0, 1, 2 and 6 months |

| HAV | Existe vacuna combinada del VHB y VHA |

Administer 2 doses: 0 and 6 months If CD4+ cell count < 350, administer 3 doses (0, 1 and 6 months) Request prevaccine markers for individuals born before 1977 |

| HPV | 9-Valent vaccine (HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 y 58). | Administer 9-valent vaccine, 3 doses: 0, 2 and 6 months |

| Meningococcus | Monovalent (serogroup C), 4-valent (serogroups A/C/W/Y) and recombinant (serogroup C, 2- and 4-antigenic) conjugate vaccine |

Administer 4-valent vaccine (MenACWY), 2 doses: 0 and 2 months Assess the booster every 5 years |

| ATTENUATED LIVE VACCINES | ||

| Measles, Rubella, Mumps | Triple viral vaccine with high immunogenicity | Administer 2 doses: 0 and 1 months |

| Herpes zoster | Recombinant vaccine with Ag (glycoprotein E) of the varicella zoster virus | 2 doses: 0 and 2 months |

| TRAVELERS | ||

| Yellow fever | Attenuated live viral vaccine |

1 dose (CD4+ cell count > 200 cell/µL and age < 60 years old) Reminder every 10 years (if the risk persists) |

| Rabies | Composed of inactivated viruses |

3 doses: 0, 7 and 28 days (fourth dose, if insufficient serological response) Repeat +1 year and every 3-5 years |

| Typhoid fever | Vi capsular polysaccharide Ag vaccine | Single dose (can be repeated/3 years) |

| Oral attenuated vaccine |

4 doses, taken/48 hours 2 weeks before traveling Contraindicated if CD4 cell count < 200 cell/µL |

|

| OTHER VACCINES | ||

| COVID-19 |

SARS-CoV-2 vaccine mRNA vaccines, viral vectors, based on proteins and inactivated viruses |

Number of doses based on selected vaccine |

Ag: antigen; HAV: hepatitis A virus; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HPV: human papilloma virus

3.3. Current Antiretroviral Treatment Management

What are the recommendations for ART monitoring?

ART consists of a combination of two or three antiretroviral drugs. Laboratory evaluation and aspects related to the choice and monitoring of ART are specified in the corresponding GeSIDA guidelines (table 7)18.

It is essential to know the main side effects of antiretroviral drugs and to avoid polypharmacy, interactions, and new side effects (A-I).

Special situations, such as pregnancy, tuberculosis, and/or comorbidities, require extreme precautions in monitoring and treatment (A-I).

Table 7 Recommended starting antiretroviral treatment combinations as preferred regimen

| THIRD DRUG | REGIMEN | COMPONENTS |

|---|---|---|

| Integrase inhibitor | BIC/FTC/TAF | |

| DTG/ABC/3TC |

ABC is contraindicated in patients with positive status for HLA-B*5701 Do not use in patients with chronic hepatitis B |

|

| DTG+FTC/TAF* | ||

| DTG/3TC |

Not recommended in patients with baseline figure of CD4+ cell count < 200 cell/µL Do not use in patients with chronic hepatitis B Not recommended after failure of PrEP without the result of resistance study |

Preferred regimens: regimens applicable to most patients, who in randomized clinical trials have shown efficacy not lower or greater than other regimens also considered currently as preferred and present additional advantages due to the number of tablets, resistance barrier, tolerance, toxicity or a low risk of pharmacological interactions18.

*The use of TFV as TDF can be considered an alternative to TAF, when it is not combined with a potentiated drug and as long as the presence of renal impairment and osteopenia/osteoporosis is ruled out, and there are no other factors for developing them.

How to manage interactions and polypharmacy?

Collaboration between PC and HC professionals is critical in order to avoid severe interactions and to reduce the risk of polypharmacy (B-III).

ART and concomitant medication should be accessible to all prescribing physicians in real-time (B-II).

All medication for PLWH should be reviewed at every clinical visit, especially if the medication is to be modified. Online tools like the one developed by the University of Liverpool (available at: https://www.hiv-druginteractions.org/) can be used to assess interactions. Contraindications should be considered, and dose adjustments made when necessary (A-II).

How to monitor adherence and control ART?

Adherence to ART should be monitored at each clinical visit. This should be done through multidisciplinary collaboration between healthcare professionals (A-II).

Adherence to ART should be recorded in the clinical history. This information should be shared between PC and HC (C-III).

The use of two independent methods for measuring adherence is recommended. Pharmacy records and simple validated questionnaires are easily accessible in the clinic (C-III).

Healthcare for PLWH should include implementing adherence improvement programs, such as sending reminders via mobile devices or patient education programs (B-I).

3.4. Management of comorbidities

Cardiovascular risk

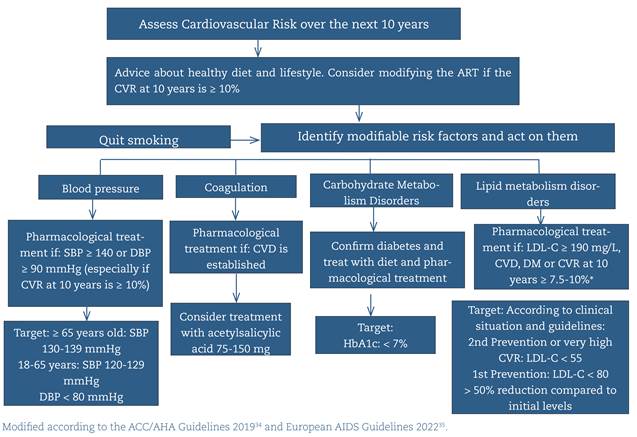

Cardiovascular risk (CVR) should be assessed in the initial evaluation and repeated annually with any of the available tools (Framingham, REGICOR, D:A:D, ACC/AHC...) (A-I).

Patients should be encouraged to change their lifestyle, including avoiding smoking (the main modifiable CVR factor), adopting a diet more suited to their needs, and providing the necessary physical exercise (A-II).

In managing dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and high blood pressure, using the same therapeutic algorithm as in the general population is recommended, while taking interactions with ART into account (A-II) (figure 2).

HbA1c should be requested before starting ART. Subsequently, in patients with diabetes, it should be monitored every six months to maintain a level < 7% (A-I).

Interactions between the drugs used (mainly statins) and some antiretroviral drugs should be considered (A-II).

Hepatic, respiratory, renal, bone, and CNS comorbidities

In patients with HIV infection, all hepatic, renal, bone, pulmonary, and/or CNS comorbidities should be evaluated at each clinical visit (HC and PC). Preventive screening and, if necessary, modification of lifestyle habits, antiretroviral therapy, and specific treatment of the healthcare issue should be performed. (A-I). (table 8).

Table 8 Comorbidity screening

| COMORBIDITY | SCREENING | DECISIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatic | ||

| Cirrosis por VHC tras RVS12 | Hepatocarcinoma |

Ultrasound every 6 months Potentially avoidable if LS < 14 kPa in SVR12 |

| Esophageal varicose veins |

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy every 2-3 years until the emergence of varicose veins with risk of bleeding and start of prophylaxis Do not screen if LS < 30 kPa and platelets > 110,000 in SVR12 |

|

| Infection by HBV | Hepatocellular carcinoma | PAGE-B > 10: biannual ultrasound |

| FLD-MS | Liver fibrosis |

Measure transaminases and request liver ultrasound in case of high values Prevention: treating obesity, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia |

| Respiratory | ||

| Lung cancer | Not indicated | Prevention: treat tobacco habit |

| Renal | ||

| Kidney disease | Kidney function impairment | CKD-EPI and basic urinalysis every 6 months |

| Bone | ||

| Osteoporosis | Annual FRAX in men > 50 years old and postmenopausal women | |

| Risk of fractures |

DEXA in:

Men and premenopausal women ≥ 40 years old in which FRAX estimates a high risk of fracture (> 3% in hip and/or major fracture > 10% at 10 years). Adults of any age with higher risks factors to present fracture due to fragility (glucocorticoid use, history of fragility fracture, high risk of falls) Post-menopausal women Men ≥ 50 years old |

|

| Central nervous system | ||

| Cognitive impairment | Not indicated | Prevention: reduction of CVR |

CKD-EPI: Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration; CVR: Cardiovascular Risk; DEXA: Bone Density Scan; FLD-MS: Fatty Liver Disease associated with Metabolic Syndrome; HBV: Hepatitis B Virus; LS: Liver Stiffness.

HIV-associated infections

Knowing the vaccination status, the patient's immunological status, and the use of prophylaxis for opportunistic diseases will help to establish an appropriate differential diagnosis for an infectious condition (A-II). The GeSIDA document on the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections and other coinfections in PLWH19 has recently been updated.

Perform STI screening in sexually active patients at least once a year (or more frequently, depending on individual risk assessment) (A-II) (table 9).

Active search for parasitosis in patients from specific countries (migrants, travelers...) (A-II).

Table 9 Screening for sexually transmitted infections

| ETIOLOGICAL AGENT | DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|

| Treponema pallidum | Serology (treponemal test + nontreponemal test for syphillis) |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | Multiplex PCR (vaginal, rectal and oropharyngeal swab according to sexual practices) |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Optical microscopy, culture, multiplex PCR (vaginal, rectal and oropharyngeal swab according to sexual practices) |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | Cervical, vaginal, urethral exudate Optical microscopy and PCR (vaginal swab) |

| Human papilloma virus | Vaginal, anal cytology (according to sexual practices) PCR |

PCR: polymerase chain reaction.

Screening for neoplasms

In the first year after the diagnosis of HIV infection, it is recommended to perform two cervical cytology tests (every six months). If both are normal, they should be repeated annually, including the inspection of the anus, vulva, and vagina (B-III).

Breast and colon cancer screening should be performed according to the recommendations for the general population (B-III).

-

In immunosuppressed patients (B-III):

Currently, anal cytology, followed by high-resolution anoscopy if the cytology is abnormal, represents the method of choice for screening for squamous intraepithelial lesions (B-II). Annual anal cytology is recommended for PLWH of the GBMSM group (especially >35 years or advanced immunosuppression) and women with lower genital tract dysplasia (B-III).

PLWH with liver cirrhosis and those with HBV infection and estimated risk of hepatocellular carcinoma greater than 0.2% per year should be screened by biannual liver ultrasound (A-I).

Neuropsychiatric alterations in HIV infection

In PLWH, it is advisable to assess their emotional health, paying attention to coping strategies and stigma (A-III). In places where there is no free choice of a mental health specialist, it is recommended to study the case and authorize the requested changes of specialists.

Validated scales such as the HADS can be used to screen for anxiety and depression at the time of diagnosis and on an annual or biennial basis (A-III).

If depressive symptomatology is identified, suicide risk should be assessed using the MINI structured interview (B-II).

3.5. Particular aspects of the follow-up of women with HIV

Pregnancy

Pregnancy is a criterion for an immediate referral from PC to HC. To avoid vertical transmission, all women with HIV should receive ART as early as possible, preferably before conception (A-II).

The ART of choice should be triple therapy. Abacavir-lamivudine or TDF-emtricitabine combinations plus a third drug, which may be raltegravir, dolutegravir, or darunavir/ritonavir, are of choice. The choice will depend on the time of initiation (whether prior to conception or not), the history of resistance or intolerance, and the patient's preference (A-II).

Intrapartum treatment with IV zidovudine is indicated if the plasma viral load is > 1000 copies/ml or unknown at delivery time (A-I).

During delivery, cesarean section is indicated in women with confirmed or suspected viral load of more than 1000 copies/ml (A-II). It is recommended in women with a viral load between 50-1000 copies/ml, although each case should be personalized (B-III).

In these circumstances, breastfeeding is not recommended (A-II).

Conception, contraception, menopause

In PLWH, family planning must be done in the best possible clinical situation, minimizing the risks for the woman, the couple, and the fetus, explaining the different reproductive options (A-II) (table 10).

It is recommended to evaluate the age of onset of menopause, considering the symptoms associated with menopause, premature aging, and comorbidities. Hormone replacement therapy can be assessed with the same indications as in the general population (A-III).

DEXA is advised in postmenopausal women with HIV infection (A-I).

Table 10 Reproductive options based on the follow-up of the infection in the partner

| SITUATION | MEASURE |

|---|---|

| Man or woman with HIV infection without virological control |

Wait until virological control If this option is not possible: Sperm washing and insemination Use pre-exposure prophylaxis If it is the woman who has the HIV infection, self-insemination is an option. |

| Woman with HIV infection without virological control | If it is not possible to wait for virological control, self-insemination is an option |

| Woman or man with HIV infection with suppressed viral load | Natural conception is an option during the time of highest fertility |

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

3.6 Toxic habits

It is recommended to ask about tobacco use at least once every two years and advise patients to quit smoking by providing help through specific intervention (A-I).

Factors that negatively influence adherence to ART (alcohol and other drug abuse) should be addressed from PC and dealt with available resources (B-II).

Refer PLWH with alcohol dependence (B-III), severe nicotine use disorder (A-III), or problematic drug use (including chemsex) to specialized Addiction Care. The comprehensive approach to chemsex users is detailed in the specific guidelines20.

The treatment of choice for cannabis, cocaine, and MDMA abuse is psychotherapy and/or psychoeducation (B-II).

Agreed-upon protocols for interdisciplinary work and referral between hospital emergency departments, PC, STI centers, HIV units, mental health and addiction resources, and community-based organizations should be designed and implemented (A-III).

Preferential care centers for chemsex users should be identified in each city. A referral professional should be assigned to each user to follow up on the case and coordinate referrals between services (A-III).

4. SOCIAL ASPECTS

How can the social determinants of vulnerability be approached?

A gender approach should be incorporated, and all types of diversity (sexual, gender, class, functional, cognitive, age, and cultural) should be considered, along with the structural factors at the intersection of health and HIV, taking them into account when recording medical histories and while providing health care (A-II).

Interventions must be adapted to the particularities of vulnerable PLWH (GBMSM, sex workers, transgender people, people with problematic drug use, and migrants), improving the interaction between socio-community services and PC/HC. (B-II).

Assessment of health-related quality of life

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in PLWH should be assessed to personalize and improve health care (B-II).

The EQ-5D-5L instrument is one of the most commonly used tools for cost-efficiency calculations or comparisons with the general population. If the aim is to determine the degree to which different dimensions of HRQOL are affected, the WHOQOL-HIV-BREF is a reliable questionnaire with psychometric evidence for PLWH in Spain21,22 (B-III).

HC typically has the most favorable settings to determine the HRQoL for PLWH, but the results should be shared with PC (B-III).

Ideally, HRQoL should be recorded at the beginning of ART and annually before the follow-up consultation in HC (B-III).

Legal and ethical aspects. Confidentiality

HIV testing should be informed and consented to by the patient. Healthcare facilities should ensure that the test is performed and the results are reported in a confidential manner (A-I).

Training of healthcare and administrative personnel involved in the care of PLWH on privacy and confidentiality issues should be increased for all age ranges, considering the impact of gender, disability, and culture (A-III).

The rights to privacy and data protection of PLWH should be guaranteed if there is no risk of transmission (see the original document where particular situations are detailed)1.

5. SHARED TEACHING AND RESEARCH IN HIV INFECTION

Regular teaching sessions should be agreed upon to generate shared knowledge regarding screening, management of HIV infection, comorbidities, and social, ethical, and legal aspects (A-II). Online formats and flexible schedules should be sought (B-III).

The development of joint meetings between different healthcare settings should be encouraged concerning the shared care of PLWH and those at risk of acquiring HIV (A-III).

Shared research between PC and HC should be promoted by creating multidisciplinary working groups on various topics (prevention, screening, connection to care, adherence to treatment, interactions, polypharmacy, management of comorbidities, quality of life, continuity of care) (B-III).

REFERENCES

1. Panel de expertos del Grupo de estudio de SIDA (GeSIDA) y de la Sociedad Española de Medicina de Familia y Comunitaria (semFYC). Manejo compartido del paciente con infección por VIH entre Atención Primaria y Hospitalaria. [Internet]. GESIDA. semFYC; 2022 [consultado: el 25 de enero de 2023]. Disponible en: https://gesida-seimc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/manejo-compartido-del-paciente-con-infeccion-por-vih.pdf [ Links ]

2. Martínez E, Arribas JR, Polo R (coord.). Documento de consenso de GeSIDA/Plan Nacional sobre el sida respecto al tratamiento antirretroviral en adultos infectos por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana. Actualización enero 2022. [Internet]. GeSIDA; 2022 [consultado: 25 de enero de 2023]. Disponible en: https://gesida-seimc.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/GuiaGeSIDAPlanNacionalSobreElSidaRespectoAlTratamientoAntirretroviralEnAdultosInfectadosPorElVirusDeLaInmunodeficienciaHumanaActualizacionEnero2022.pdf [ Links ]

3. Ayerdi Aguirrbengoa O, Coll Verd P (coord.). Recomendaciones sobre la profilaxis pre-exposición para la prevención de la infección por VIH en España. [Internet]. GeSIDA - SEIMC; 2023 [consultado: 25 de enero de 2023). Disponible en: https://gesida-seimc.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/DocumentoGesidaPrEP2022Final.11.01.23.pdf [ Links ]

4. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, et al. Revised Recommendations for HIV Testing of Adults, Adolescents, and Pregnant Women in Health-Care Settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006; 55:1-CE-4. [ Links ]

5. HIV in Europe. Enfermedades indicadoras de infección por VIH: Guía para la realización de la prueba del VIH a adultos en entornos sanitarios. [Internet]. HIV in Europe; 2011 [consultado: 25 de enero de 2023]. Disponible en: https://www.eurotest.org/media/0ymdzdvu/guidancepdf.pdf [ Links ]

6. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. HIV testing: increasing uptake and effectiveness in the European Union. [Internet]. Stockholm: ECDC; 2010 [consultado: 25 de enero de 2023]. Disponible en: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/media/en/publications/Publications/101129_GUI_HIV_testing.pdf [ Links ]

7. Ministerio de Sanidad Servicios Sociales e Igualdad e Instituto Nacional sobre el Sida. Guía de recomendaciones para el diagnóstico precoz de VIH en el ámbito sanitario. [Internet]. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad; 2014. [consultado: 25 de enero de 2023]. Disponible en: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/ciudadanos/enfLesiones/enfTransmisibles/sida/docs/GuiaRecomendacionesDiagnosticoPrecozVIH.pdf [ Links ]

8. Domínguez-Berjón MF, Pichiule-Castañeda M, García-Riolobos MC, Esteban-Vasallo MD, Arenas-González SM, Morán-Arribas M, et al. A feasibility study for 3 strategies promoting HIV testing in primary health care in Madrid, Spain (ESTVIH project). J Eval Clin Pract. 2017; 23:1408-14. [ Links ]

9. Puentes Torres RC, Aguado Taberné C, Pérula de Torres LA, Espejo Espejo J, Castro Fernández C, Fransi Galiana L. Aceptabilidad de la búsqueda oportunista de la infección por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana mediante serología en pacientes captados en centros de atención primaria de España: estudio VIH-AP. Aten Primaria. 2016; 48:383-93. [ Links ]

10. Martínez-Sanz J, Vivancos MJ, Sánchez-Conde M, Gómez-Ayerbe C, Polo L, Labrador C, et al. Hepatitis C and HIV combined screening in primary care: A cluster randomized trial. J Viral Hepat. 2020; 28:345-52. [ Links ]

11. Agustí C, Martín-Rabadán M, Zarco J, Aguado C, Carrillo R, Codinachs R, et al. Early diagnosis of HIV in Primary Care in Spain. Results of a pilot study based on targeted screening based on indicator conditions, behavioral criteria and region of origin. Aten Primaria. 2018; 50:159-65. [ Links ]

12. Cayuelas Redondo L, Ruiz M, Kostov B, Sequeira E, Noguera P, Herrero MA, et al. Indicator condition-guided HIV testing with an electronic prompt in primary healthcare: A before and after evaluation of an intervention. Sex Transm Infect. 2019; 95:238-43. [ Links ]

13. De la Fuente L, Delgado J, Hoyos J, Belza MJ, Álvarez J, Gutiérrez J, et al. Increasing Early Diagnosis of HIV through Rapid Testing in a Street Outreach Program in Spain. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2009; 23:625-9. [ Links ]

14. Fernández-Balbuena S, Belza MJ, Zulaica D, Martínez JL, Marcos H, Rifá B, et al. Widening the access to HIV testing: The contribution of three in-pharmacy testing programmes in Spain. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0134631. [ Links ]

15. Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad y Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos. Guía de actuación farmacéutica en la dispensación de productos sanitarios para autodiagnóstico del VIH. [Internet]. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad; 2017 [consultado: 22 de febrero de 2023]. Disponible en: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/eu/ciudadanos/enfLesiones/enfTransmisibles/sida/docs/diagnosticoPrecozVIH_05_Accesible.pdf [ Links ]

16. Martínez Chamorro E, Arribas López JR, Mariño Callejo A, Montes Ramírez ML, Suárez García I, Viciana Ramos I, et al. Panel de expertos del grupo de estudio de SIDA (GeSIDA). Documento de consenso sobre teleconsulta (TC) con personas que viven con infección por VIH (PVVIH). [Internet]. GeSIDA; 2021. Disponible en: https://gesida-seimc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/TELECONSULTA_Guia_GeSIDA.pdf [ Links ]

17. Thompson MA, Horberg MA, Agwu AL, Colasanti JA, Jain MK, Short WE, et al. Primary Care Guidance for Persons With Human Immunodeficiency Virus: 2020 Update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2021; 73:e3572-e3605. [ Links ]

18. Palacios R, Arribas JR, Polo R (coord.). Panel de expertos de GeSIDA y Plan Nacional sobre el Sida. Documento de consenso de GeSIDA/Plan Nacional sobre el Sida respecto al tratamiento antirretroviral en adultos infectados por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana. [Internet]. 2023 [Actualización: enero 2023; consultado: 3 de marzo de 2023]. Disponible en: https://gesida-seimc.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Guia_Modificada_DocumentoDeConsensoDeGeSIDAPlanNacionalSobreElSidaRespectoAlTratamientoAntirretroviralEnAdultosInfectadosPorElVirusDeLaInmunodeficienciaHumana.pdf [ Links ]

19. Documento de prevención y tratamiento de infecciones oportunistas y otras coinfecciones en pacientes con infección por VIH. [Internet]. GeSIDA; 2021. [consultado: 25 de enero de 2023]. Disponible en: https://gesida-seimc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/GUIA_PREVENCION_INFECCIONES_OPORTUNISTAS.pdf [ Links ]

20. Soriano Ocón R (coord.). Abordaje del fenómeno del chemsex. Secretaría sobre el Plan Nacional sobre el Sida. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad; 2020. [ Links ]

21. Fuster-Ruizdeapodaca MJ, Laguía A, Safreed-Harmon K, Lazarus JV, Cenoz S, Del Amo J. Assessing quality of life in people with HIV in Spain: psychometric testing of the Spanish version of WHOQOL-HIV-BREF. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):144. [ Links ]

22. Hernández G, Garin O, Pardo Y, Vilagut G, Pont A, Suárez M, et al. Validity of the EQ-5D-5L and reference norms for the Spanish population. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:2337-48. [ Links ]

23. Tu D, Belda P, Littlejohn D, Pedersen JS, Valle-Rivera J, Tyndall M. Adoption of the chronic care model to improve HIV care: In a marginalized, largely aboriginal population. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59:650. [ Links ]

24. Goetz MB, Bowman C, Hoang T, Anaya H, Osborn T, Gifford AL, et al. Implementing and evaluating a regional strategy to improve testing rates in VA patients at risk for HIV, utilizing the QUERI process as a guiding framework: QUERI Series. Implement Sci 2008; 3:16. [ Links ]

25. Gómez-Ayerbe C, Martínez-Sanz J, Muriel A, Pérez Elías P, Moreno A, Barea R, et al. Impact of a structured HIV testing program in a hospital emergency department and a primary care center. PLoS One. 2019; 14:e0220375. [ Links ]

26. Rogers GD, Barton CA, Pekarsky BA, Lawless AV, Oddy JM, Hepworth R, et al. Caring for a marginalised community: the costs of engaging with culture and complexity. Med J Aust 2005; 183:S59-S63. [ Links ]

27. Cabral HJ, Davis-Plourde K, Sarango M, Fox J, Palmisano J, Rajabiun S. Peer Support and the HIV Continuum of Care: Results from a Multi-Site Randomized Clinical Trial in Three Urban Clinics in the United States. AIDS Behav 2018; 22:2627-39. [ Links ]

28. Kay ES, Lacombe-Duncan A, Pinto RM. Predicting Retention in HIV Primary Care: Is There a Missed Visits Continuum Based on Patient Characteristics? AIDS Behav. 2019;23:2542-8. [ Links ]

29. Page J, Weber R, Somaini B, Nöstlinger C, Donath K, Jaccard R, et al. Quality of generalist vs. specialty care for people with HIV on antiretroviral treatment: a prospective cohort study. HIV Med 2003; 4:276-86. [ Links ]

30. Hutchinson J. HIV services - what role for primary care? Drug Ther Bull. 2011;49:85. [ Links ]

31. Kendall CE, Shoemaker ES, Porter JE, Boucher LM, Crowe L, Rosenes R, et al. Canadian HIV Care Settings as Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMHs). J Am Board Fam Med 2019; 32:158-67. [ Links ]

32. Webel A, Prince-Paul M, Ganocy S, DiFranco E, Wellman C, Avery A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a community navigation intervention to improve well-being in persons living with HIV and other co-morbidities. AIDS Care 2019; 31:529-35. [ Links ]

33. Riera M, Ferre A, Santos-Pinheiro A, Vilchez HH, Martin-Peña ML, Ribas MA, et al. Pilot Program of Shared Assistance with Primary Care in Patients Living with HIV, and Satisfaction with The Healthcare Received. [Internet]. EACS 2019. (Consultado: 25 de enero de 2023). Disponible en: https://europepmc.org/article/ppr/ppr351221 [ Links ]

34. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. [Internet]. Circulation. 2019 [consultado: 3 de marzo de 2023]; 140:e596-e646. Disponible en: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678 [ Links ]

35. European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS). Guidelines version 11.1. EACS; October 2022. [ Links ]

iThis article is published simultaneously, within the framework of the corresponding publication and copyright agreement, in: Revista Clínica de Medicina de Familia and in Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica.

iiThe complete version of the document can be found online at https://gesida-seimc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/manejo-compartido-del-paciente-con-infeccion-por-vih.pdf

texto en

texto en