INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus strain in which the virus and disease were unknown before the outbreak that began in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 [1, 2]. World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 as pandemic on 11 March 2020 [3]. Although the disease causes mild illness for most people (80%), it can be serious with some others (15%) and for few (5%) could be fatal and appear more vulnerable especially for older people and those with underlying medical problems [4]. According to WHO, the most common symptoms include fever, cough, shortness of breath, muscle pain, diarrhoea, sore throat, loss of smell and taste, as well as abdominal pain. Presently, although some vaccines are approved, several potential medication candidates are not [5], instead, control of the spread of the infection is being recommended by prevention. This include avoiding exposure to the virus by several ways such as use of face mask, wash hands with soap and avoiding crowded places [6, 7].

Minister of Health of Libyan Government announced on March 24, 2020, that the first infection case with the isolated new-corona virus was registered in Libya [8]. According to the National Center for Disease Control (NCDC), "the infection was confirmed, where the infected person is a 73-year-old who returned from Saudi Arabia via Tunisia and developed symptoms more than a week after his return to the country [9]. It should be noted that tracking the COVID-19 in Libya began early, since January 2020. During the COVID-19 disease, although Libya is experiencing comprehensive instability and divisions in its national institutions, and uneven weakness in its health systems, but it is commendable that the NCDC is unified in the country and works according to its limited capabilities with the utmost precision, transparency and scientificalness. NCDC has announced that the necessary measures had been taken in terms of preparations in accordance with the instructions of the WHO, indicating that Libya was classified as one of the least dangerous countries for the outbreak of the disease [10]. Upon the fact that most of the Libyan people are susceptible to COVID-19 as others elsewhere, it is extremely challenging to prevent and control the spread of this infectious disease between people. Many published articles have indicated that attitude, opinion and practice with respect to the disease are significantly correlated with protective behaviour [11, 12, 13, 14]. A negative evaluation to the government support during the pandemic is clear from participant's replies [15]. Knowledge of the public can play a major role in prevention and control of COVID-19 [16]. Accordingly, the aim of this study is to assess the public's impact of these factors towards COVID-19 pandemic in Libya.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

MATERIALS AND METHODS

STUDY DESIGN AND INSTRUMENTS

Due to quarantine at the time, a cross-sectional online survey was conveyed from 15th September until 29th of October 2020. After review of literature, a modified-design and pre-validated questionnaire that was derived from questionnaires used in previous published studies [6, 17, 18] to be compatible with the Libyan population. The questionnaire was written in Arabic language and then translated to English by an expert. People were invited to participate in the questionnaire, where the objective of the study was explained at the beginning of the questionnaire and each participant asked for his/her approval to be involved in the study, which were assured of confidentiality by the researchers. A pilot-tested in a sample of 50 participants, who agreed to be involved in the study, was carried out to ensure the level of validity and degree of repeatability, and they then were excluded from the actual study. Based on the Cronbach's alpha coefficient, the value of alpha was found 0.668, which is an acceptable measure of reliability or internal consistency [19]. Data was collected by an anonymous-structured questionnaire via a google link and put on different Libyan social media platforms to ensure more publicity. The inclusion criteria include capability to understand the questions and ≥18 years old, while the exclusion criteria were unable to fill in the questionnaire due to illness or other reasons, <18 years of age and refuse to participate. Based on the study purpose, the questionnaire was consisting of 23 questions to access the experience of Libyan people toward COVID-19 during the period from March to August 2020. Questions of the questionnaire were divided into five sections including demographic characteristic variables, attitude, awareness, opinion and practices with respect to COVID-19. The demographic variables were gender, age, education level, and place of residence. There were five questions in the attitude section, which include the fear from infection, suffer from chronic diseases, taking the prescribed medications if they suffer from other illness, development of any respiratory symptoms of the disease and adhere to the precautionary measures. To assess the awareness section, five options were put as 100% (highly strong awareness), 80 % (strong awareness), 50% (moderate awareness), 20 % (weak awareness) and 0 % (no awareness). The opinion section of the Libyans towards the responsible authority's measures in the country involved four questions. Each question contains five options include strongly agree (100%), agree (80%), not sure (50%), disagree (20%) and strongly disagree (0%). The section of practices of Libyans in the context of the events of the COVID-19 pandemic contains nine questions. Each one contains five options which are “always”, “often”, “sometimes”, “rarely” and “no”.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data collected from the survey were analyzed using statistical package for social sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) version 25. The gender, age, level of education, and residence were the independent variables for the present study, while the dependent one was the other sections. A descriptive statistical was used to calculate proportions and frequencies, furthermore analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine the differences between demographic variables and the opinion as well as practice towards COVID-19. Data of opinion and practice score were measured as (mean ± SD) and the statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Only three participants were excluded from the study because of their age (<18 years). Then, 2,305 subjects were involved in this study. The demographic details of the participants involved in this study are shown in Table 1. The response rates of the participants, from the four main regions of Libya, are 80% from the West region, 8.7% from the East region, 10% from the Middle region and 1.3% from the South region. The majority of the participants are females (63.1%), with the majority of the 20-50 years' age group (86.6%). Level of education among the responses are mostly university graduates (71.3%).

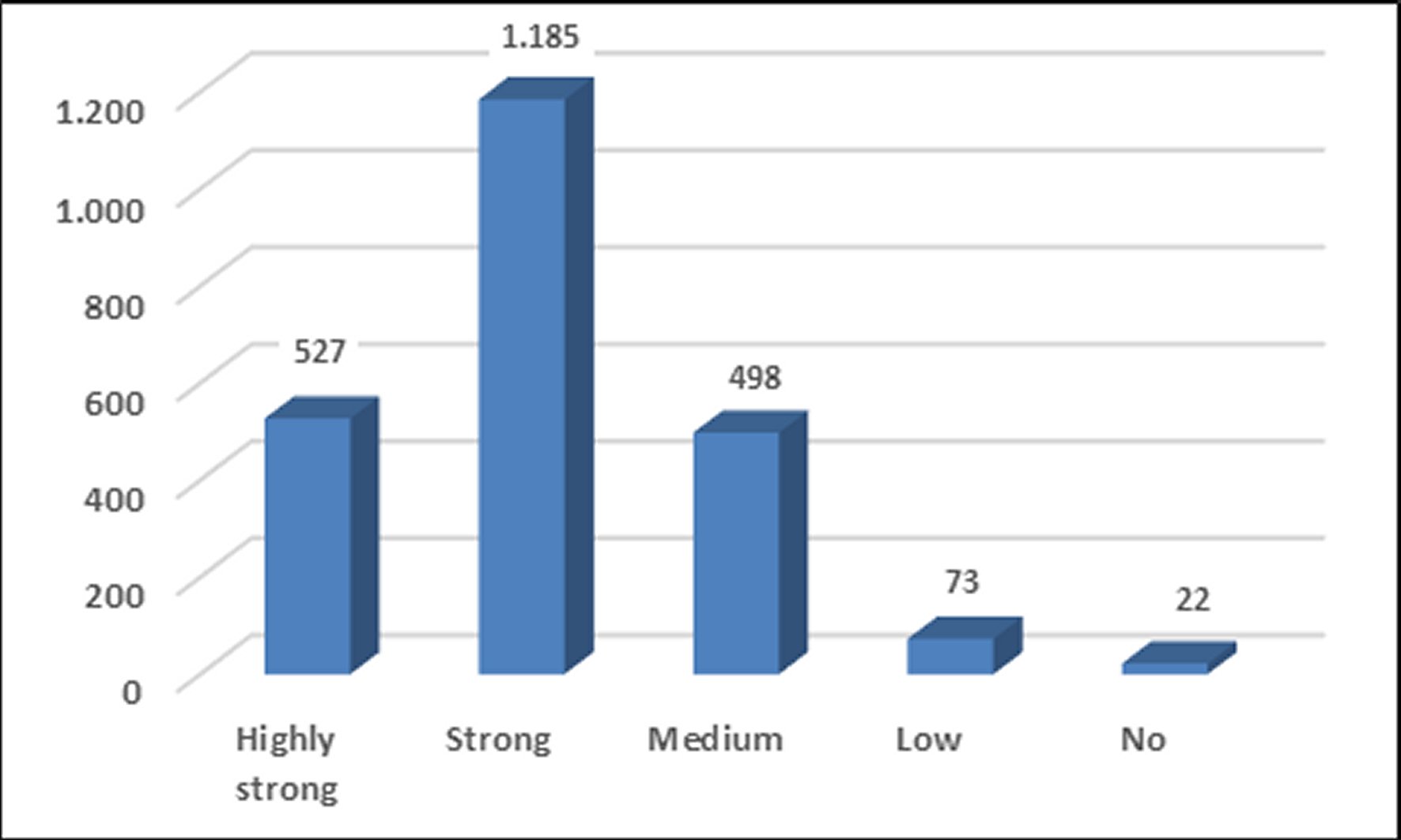

The level of awareness and understanding of the new coronavirus was given in Figure 1. The highest proportion was strong (n = 1185, 51.4%) followed by highly strong (n = 527, 22.9%). The proportions of medium, low and no awareness of the disease were (n = 498, 21.6%), (n = 73, 3.2%) and (n = 22, 0.9%), respectively.

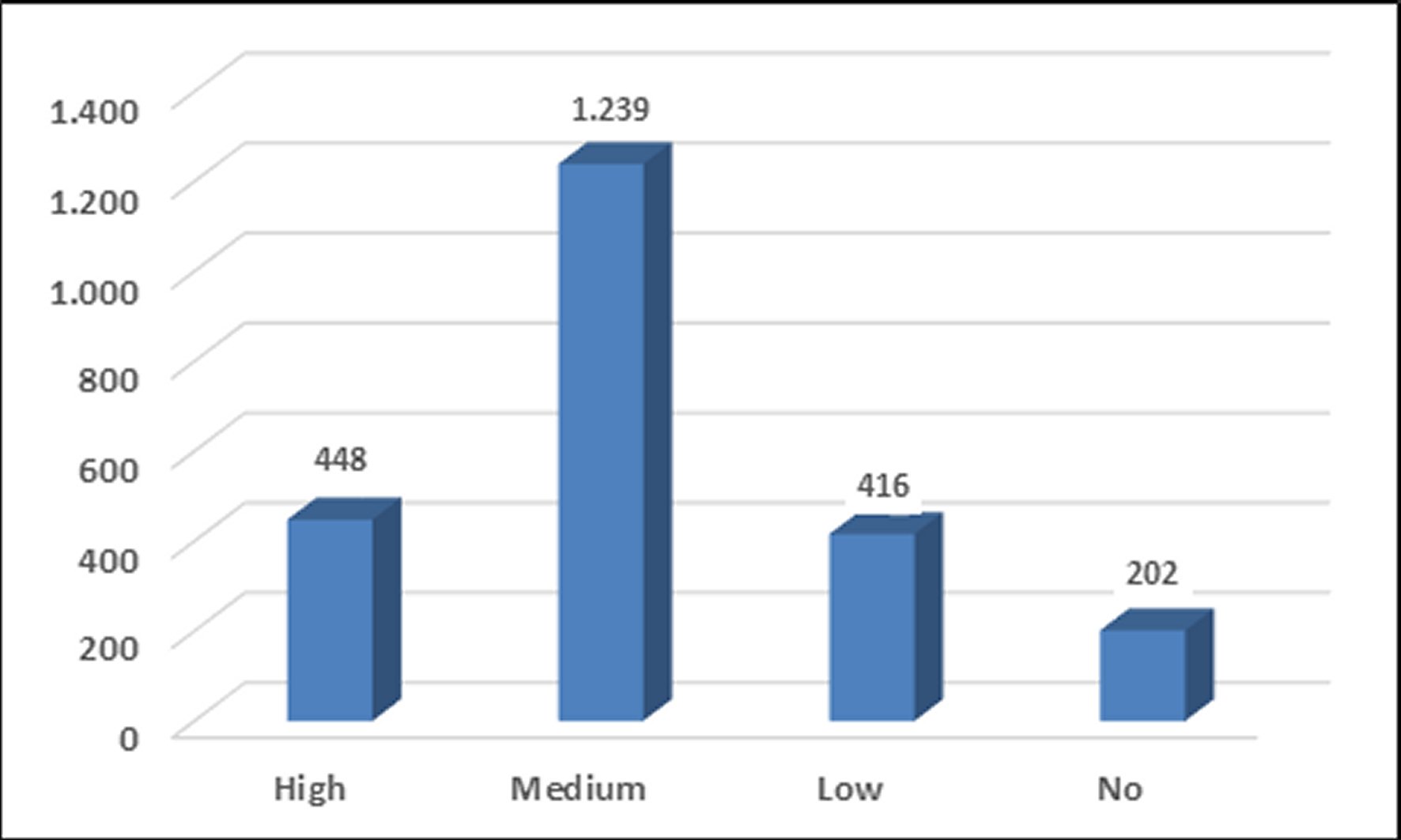

In Figure 2, the fear from infection responses were high (n = 448, 19.4%), medium (n = 1,239, 53.8%), low (n = 416, 18.0%) and no fear (n = 202, 8.8%). The low and no fear options were considered as positive results (26.9%) while high and medium reflects negative results (73.2%).

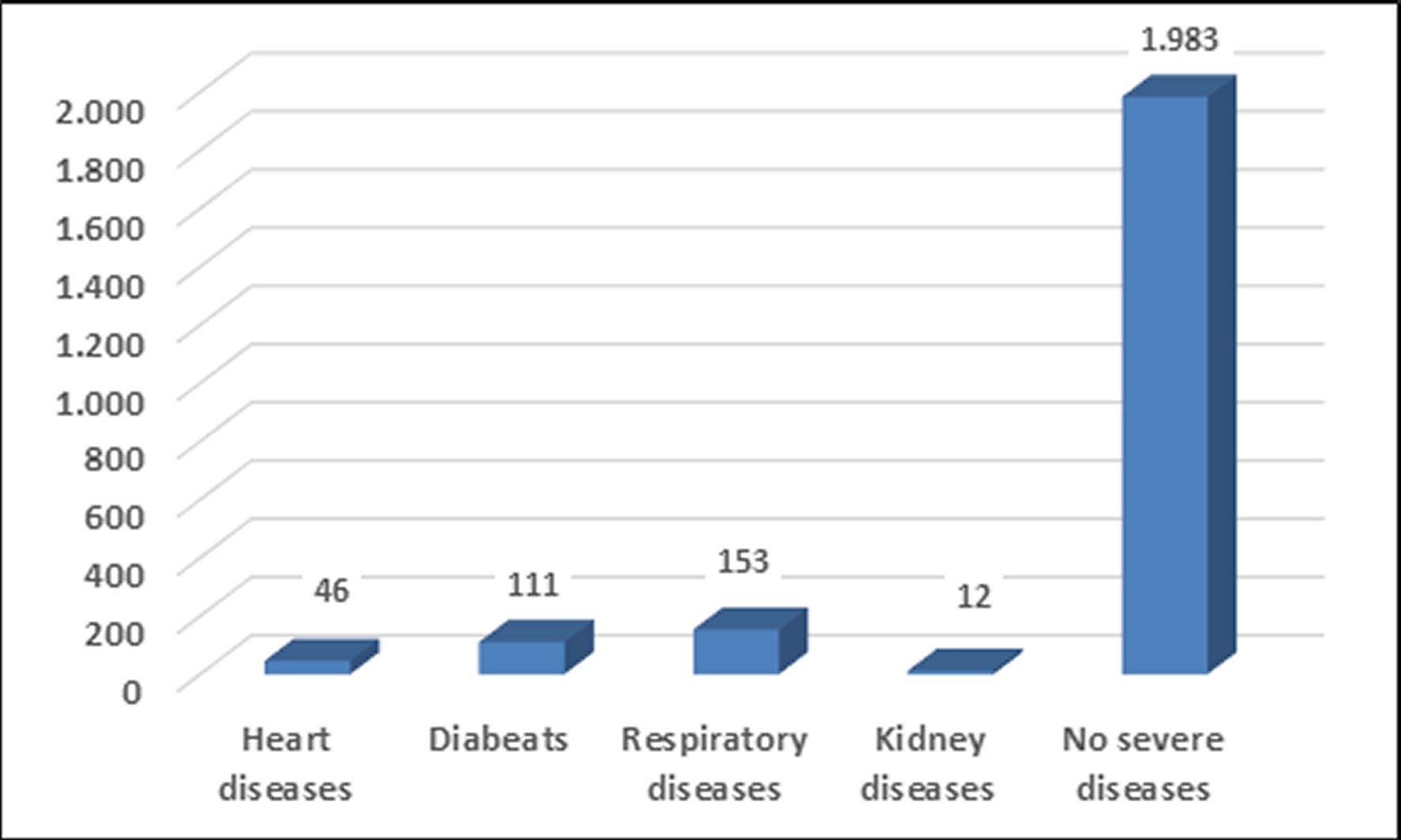

The possibility of chronic diseases presence among participants and the development of any respiratory symptoms since the onset of the disease are presented in Figures 3 and 4. Figure 3 shows the response for respiratory diseases (n = 153, 6.6%), heart disease (n = 46, 2.1%), diabetes (n = 111, 4.8%) and kidney diseases (n = 12, 0.5%), while participants who are free of the mentioned chronic diseases were the majority (n = 1983, 86 %).

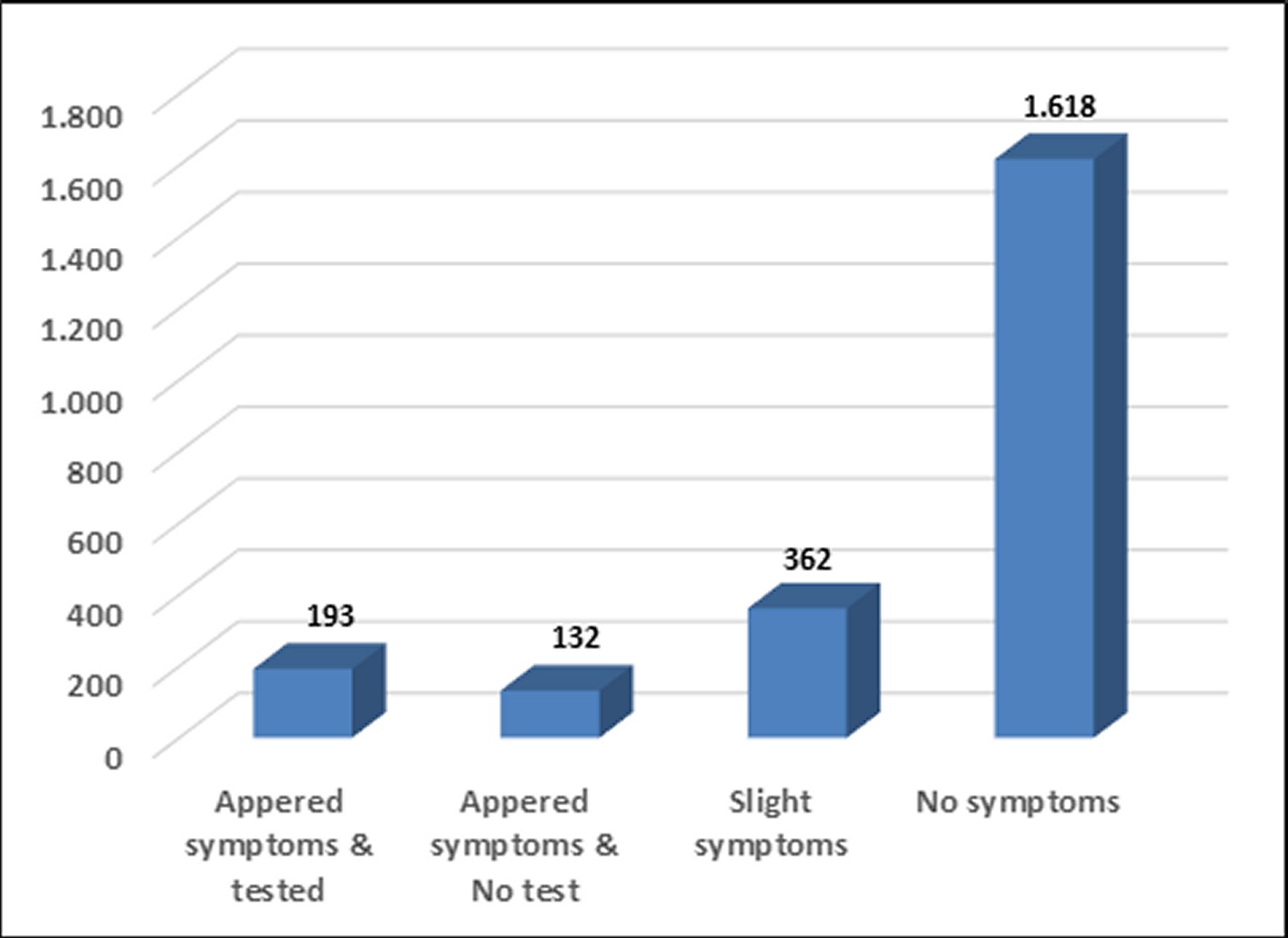

Figure 4 summarize the symptoms and the realization of COVID-19 test. Results were defined as appeared symptoms and tested, appeared symptoms & no tested, slight symptoms without test performed and no symptoms. The results were (n = 193, 8.4%), (n = 132, 5.7%), (n = 362, 15.7%) and (n = 1,618, 70.2%), respectively.

During the period from March to August 2020, when studying the participant's compliance with the preventive authorities' procedures, a slight compliance increase was found during the months of March and April, and then was decreased during the rest of months (Figure 5). In addition, a number of participants (n = 111, 4.8 %) are not interested at all in applying any precautionary measures, although a number of participants (n = 1,076, 46.8 %) has responded that they are committed in all months.

Figure 5. The participant's adhering to the authority's precaution measures from March to August 2020.ANI: Absolutely not interested.

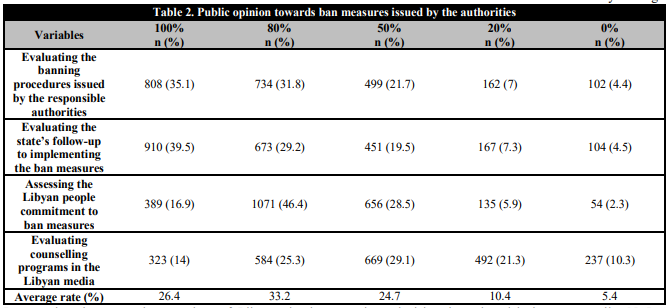

The opinion of Libyans towards the ban measures that have been taken by the authorities in the country is summarized in Table 2. The highest proportion went to disagree (20%) which is ranged from 25.3% (evaluating counselling programs in the Libyan media) to 46.4% (assessing the Libyan people commitment to ban measures) and the average rate value was 33.2%. It was followed by strongly disagree (0%) that range from 14 % (evaluating counselling programs in the Libyan media) to 39.5% (evaluating the state's follow-up to implementing the ban measures) with an average rate value of 26.4%. This opinion expresses Libyans' dissatisfaction with the measures taken by the responsible authorities, whether at the level of decisions or their follow-up on the ground.

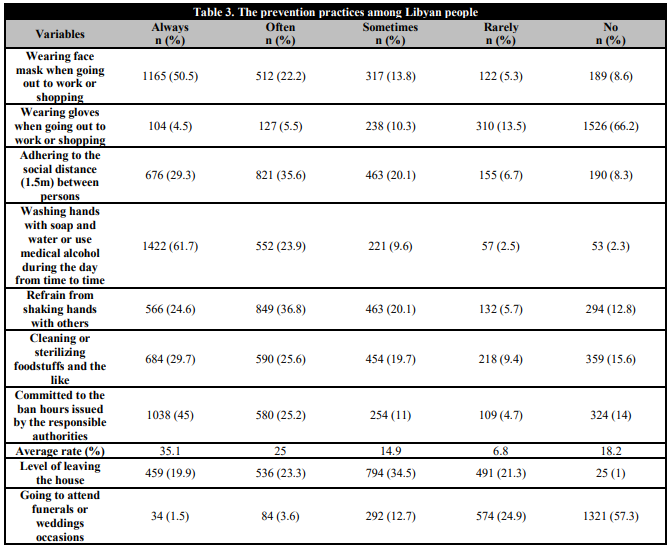

In assessing the preventive practices of Libyans in the context of the events of the COVID-19 pandemic is given in Table 3. The proportion of good practice always is ranged from 4.5% wearing gloves when going out to work or shopping to 61.7% washing hands with soap and water or use medical alcohol during the day from time to time and the average rate value was 35.1 %. On the other hand, the option no is considered as good practice for going to attend funerals or weddings occasions in which with a proportion of 57.3% expressed satisfaction with only offering condolences or joy using the phone or other social media of communication instead of personal presence. The sometimes option, which has been decided to be good practice for assessing the level of leaving the house for work or shopping, was in proportion of 34.5%.

An analysis by ANOVA revealed no difference effect statically between the score of the Libyan people's opinion towards ban measures of COVID-19 by authorities and gender (P = 0.313), age (P = 0.212), and residence (P = 0.183), while education had a statistically significant effect (P = 0.002) as shown in Table 4. The practice score of the Libyans showed a significant difference with gender (P =0.029), age (P = 0.000), education (P = 0.013) and residence (P = 0.000).

DISCUSSION

The present study reveals that COVID-19-related knowledge and understanding of the new coronavirus among Libyan people exhibited a good level and considered as strong. This may be attributed mainly to the educational level of participants [6]. In addition, the governmental released relevant education materials routinely through various television channels and the internet as well as NCDC platform since early stages of the pandemic may played an important positive effect. Health programs in Libya can be more organized to increase knowledge and awareness towards COVID-19 disease.

Participants showed responses towards the fear from infection (19.4% high and 53.8% medium, 73.2% totally). In a similar culture, more than 50% of Jordanian people were afraid from COVID-19 [20]. In addition, the current study was consistent with a study in India [21] that showed about half of the respondents were afraid of the COVID-19 pandemic. In China, fear of infection has expressed about 97% among public [6]. The present results indicating that authorities must further wonder about intense ongoing work, guidance, and adequate explanation corresponding to education in order to reduce public fear aspect. The increase of fear shall have negative influences on both the preventive intention and mental health of people [22].

Studying the possibility of chronic diseases presence among participants and the development of any respiratory symptoms since the onset of the disease, the majority of participants do not show any associated-conditions including respiratory diseases, heart disease, diabetes or kidney diseases that have been reported by to be more susceptible to suffer from COVID-19 [23]. Indeed, this is may be attributed to the majority of the age group (<50 years) among the participants. The results further indicate that the majority of participants did not show any COVID-19 known symptoms.

During the period of the study, the extent of the participant's commitment to the precautionary measures showed a slight compliance increase with preventive procedures announced by authorities during March and April. During the rest of study months, these measures have decreased which may have supported by the dramatic increase in the number of cases after that [8, 9]. The results may be attributed to a lack of public's confidence in the authority's ability to manage the pandemic [24].

Applying preventive measures is of utmost importance to reduce the spread of the disease [25]. The majority of Libyan people participated in the present study either disagree or strongly disagree to the ban measures issued by the responsible authorities in the country. This phenomenon may be related to the gap between the people and the weakness of the health system, as well as the confusion of the responsible authorities regarding the issuance of decisions towards the COVID-19 epidemic. In addition, it may also have attributed to the people behaviour change [26]. The level of knowledge about COVID-19 significantly influenced public obedience to authority's measures for controlling the epidemic [16].

The participants have adhered to good prevention practices, which is analogous with a study conducted in Bangladesh [27]. Only minority average rate has the least (rarely) practice among participants. Effective-adherence to public practice is essential towards COVID-19 [28]. In Iran of a similar awareness of Libyans, a study reveals high practice average rate among Iranian population about COVID-19 [29]. In order to improve the practice rate, the present study suggests that the authorities should work more to provide sufficient information so that the public can take further protective actions.

This study also shows that the level of the participant's commitment to the necessary precautionary measures was high, although there was a difference in commitment depending on the age of participants, their educational level and the area in which they live. Health authorities should target people by an advanced education program. For pre-graduate population, simple education materials could be more effective [30]. Improving people's knowledge is the master key to fight against the COVID-19 pandemic [31, 32].

The findings showed no statistical difference of the Libyan people's opinion score towards ban measures of COVID-19 by authorities with gender, age, and residence. The statistical analysis found that there is a difference between good, medium and poor practice scores with age, gender, education level and residence of participants. Similar results were obtained by Gao et al. [6] among Chinese people. The difference in this study is existing from one region to another, from one level of education to another, from one group of age to another, and between males and females. The reason for this difference may be due to differences in knowledge between regions and the number of participants involved in each region. These findings are useful for policymakers of health workers to recognize target populations for COVID-19 prevention and health education [31]. It is necessary to reexamine how the national government disseminates information in order to increase the degree of trust in that information among the public [32]. As for the educational level, there is no doubt that it played a role and gave an important indication with regard to the cognitive achievement of the disease. It has been reported that the level of education is significantly associated with having adequate knowledge [12, 29].

The present study was aimed to assess various impact factors on Libyan people and comparing the scores of opinion and practice with respect to COVID-19 in Libya. The findings of this study could be used in information campaigns on COVID-19 by public health authorities and the media. This evaluation is required as an attempt to help the authority's policymakers in Libya to improve preventive practices to reduce COVID-19 infection among the public, because there is no vaccine available at that time and no specific medication against the disease. Even in the presence of vaccines, the precautionary protection remain necessities associated until this dangerous epidemic being completely eliminated.

CONCLUSIONS

The Libyan people has an acceptable level of awareness and opinion in applying the necessary precautionary measures towards COVID-19 pandemic events. Prevention practices are influenced by educational level, residence, age and gender. The current study provides an insight, in order to contribute to the efforts made by the National Center for Disease Control.