Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Psychology, Society & Education

versión On-line ISSN 1989-709X

Psychology, Society & Education vol.15 no.3 Córdoba sep./dic. 2023 Epub 18-Mar-2024

https://dx.doi.org/10.21071/psye.v15i3.16092

Articles

Educational use of connectivity in childhood and adolescence: a systematic literature review

1 Universidad de Cantabria, Santander (Spain)

2 Universidad del País Vasco, Bilbao (Spain)

3 Universidad Lusófona, Lisboa (Portugal)

Internet connectivity during childhood and adolescence entails risks and opportunities in several vital areas. Specifically, this work focuses on identifying lines of research and intervention to take advantage of the digital connectivity of minors in the educational context. To this end, a systematic review of the literature based on the PRISMA method and the Web of Science and Scopus databases is proposed for the search and selection of articles. This study focuses on five key fields: historical trajectory, research methodology, findings, implications for research and educational practice, and future lines of research. Of the 68 papers analyzed, it can be observed that: (1) they have recently increased their publication; (2) qualitative approaches predominate, evaluating the effects of educational interventions, mainly on children and young people in Europe and at the Primary and Secondary Education levels; (3) it is concluded that the environments where children's digital connectivity has had a positive impact include improved learning and academic performance, digital inclusion and accessibility, digital creation and production, collaborative learning, and media and digital education; (4) it suggests fostering media literacy and digital competence education from an early age to prevent risks and take advantage of opportunities; and (5) it encourages exploring new areas to optimize the use of digital connectivity among children. This review reveals the areas digital connectivity has had a positive impact on children's education.

Keywords: Training; Internet; Children; Teenagers; Benefits

In 2003, the first literature reviews on the use of technology in childhood and adolescence began to be carried out, showing how this was limited exclusively to computers, considered only as complementary tools in education (Stephen & Plowman, 2003). Subsequently, the digital transformation of educational centers has led to an effective integration of technology (Timotheou et al., 2022). This refers not only to the incorporation of technological devices and internet connectivity in the classroom but also to the implementation of a learner-centered pedagogical approach that harnesses the potential of technology to enhance learning and skill development (Vidal-Hall et al., 2020). Even though digital connectivity has significantly improved the way students learn and collaborate, there is still a digital divide, especially in remote or low-resource areas (Kalolo, 2019). This means that equal educational opportunities have yet to be guaranteed.

In this sense, prestigious organizations such as UNESCO (2021) propose, within the framework of the evolution of the right to education, that the digitization of education should be based on two aspects: the reduction of the digital divide to increase learning opportunities and protection in cyberspace. Despite this, the study of digital connectivity among children and adolescents has focused more on the risks it may entail and how to prevent them than on the opportunities it offers, as evidenced by the study by Orben (2020), which analyses 80 systematic reviews and meta-analyses. This is due to several factors, among which stand out: (1) the concerns of teachers, families and experts about digital security and access to inappropriate content, online harassment, or scams (Romera et al., 2021); (2) the negative impact on the well-being of children and adolescents as a consequence of misuse of technology and contact with dangerous people online (Van Endert, 2021); and (3) the lack of understanding of the educational opportunities that technology offers (Ihmeideh & Alkhawaldeh, 2017).

At the same time, digital connectivity has significantly transformed the world of education and opened new opportunities for students. Previous research has pointed out some of its educational benefits, including (1) access to a wealth of information, as well as educational resources and materials (Salmerón et al., 2018); (2) the personalization of learning through online educational tools and platforms, where the educational process can be tailored to the needs of each student and offer individualized feedback and support (Panjaburee et al., 2022); (3) the improvement of collaboration between students and faculty and among students themselves, through online educational tools and platforms that have made it possible to collaborate on projects, discuss ideas, and use resources more easily and efficiently; (4) the development of interactive learning through the creation of interactive educational resources such as educational videos, simulations, or online games, in which students can be actively involved (Sahronih et al., 2019); (5) fostering creativity and content creation through blogs, videos, or podcasts (Marsh et al., 2018); and (6) the creation of a more inclusive and equitable learning environment, providing access to those who, due to geography, economic status, or functional diversity, might face limitations (García-Hernández et al., 2023; Parmigiani et al., 2021). Therefore, digital transformation is a process that can significantly improve the quality and equity of education, but requires careful planning, investment in resources and adequate teacher training (Fernández-Batanero et al., 2022).

The paradigm of research on digital connectivity in the education of childhood and adolescence is another critical issue. The review by Miller et al. (2017), based on the methodologies used in studies on student use of technologies, concludes that most focus on cross-sectional and mixed designs are limited to homogeneous samples, and do not include vulnerable groups. Other reviews on digital connectivity in children and adolescents suggest future lines of research. Specifically, Belo et al. (2016) propose studying the role of teachers and the impact on learning if the activities are digital or not, and Mantilla and Edwards (2019) suggest studying effective strategies for teaching digital skills and how to involve families in this process.

This systematic literature review aims to conduct a thorough analysis of educational contexts that have optimized the use of digital connectivity, with particular emphasis on those scenarios that have shown a positive impact on children. This study facilitates the identification and replication of strategies to enhance the quality and effectiveness of teaching in the digital era. It highlights the relevance of focusing on situations that have positively impacted the child and youth population, given their high vulnerability to influences and the dependence of their future on the quality of education they currently receive.

Method

This study presents findings from a systematic literature review based on the PRISMA 2020 standards (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses). This updated guide provides the phases to answer specific research questions and guide the review process, including identification of information sources, eligibility criteria, search strategies, study selection, data analysis, and systematization of findings (Sánchez-Serrano et al., 2022). The objective is to review the scientific literature on the use of digital connectivity in the education of children and adolescents concerning five areas of research: (1) temporal evolution, (2) research methods, (3) results obtained, (4) implications for research and educational practice, and (5) future lines of research. Together, these five areas provide a complete and in-depth view of this subject of study, from its progress over time and its methodological foundations to its practical applications and prospects.

Phase 1: Research questions

In the first phase, research questions related to these five areas were posed, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Research questions associated with the areas raised

| Research areas | Research questions |

|---|---|

| Area 1 | Q1. How are the articles published between 2013 and March 2023 distributed? |

| Area 2 | Q2. What type of research designs (quantitative, qualitative, mixed) are most used? |

| Q3. How many studies are based on evaluating the effects of a particular educational intervention? | |

| Q4. At what educational stage (early childhood, primary, secondary, post-secondary) do you focus your studies the most? | |

| Q5. Are there studies that include children and adolescents belonging to groups in vulnerable situations? | |

| Q6. If the answer to the previous question is yes, to which groups in situations of vulnerability do these children and adolescents belong (disability, ethnic-cultural minorities, socioeconomic disadvantage, rural areas, etc.)? | |

| Q7. To which country or countries do the children in the studies belong? | |

| Area 3 | Q8. What results are obtained from these studies? |

| Area 4 | Q9. What recommendations for research and practice do the studies reflect? |

| Area 5 | Q10. What future lines of research do the studies suggest? |

Phase 2: Sources of information and eligibility criteria

We have selected those articles that address the use of digital connectivity in the education of people up to 18 years of age, since these children and adolescents are the main educational agents in the study of this impact. To find them, exhaustive searches were carried out in Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus. The search parameters were adjusted to include only articles containing the corresponding descriptors in the title, abstract, keywords, and that were available in open access article format in English and/or Spanish, in Educational Sciences and Psychology in WoS or Social Sciences in Scopus. These areas were selected because they concentrate studies on this field of interest.

The search focused on studies published between 2013 and the first three months of 2023. This nearly ten-year time frame allows us to reveal advances in digital education, gain an up-to-date understanding of the field of study, identify new research trends, and manage an adequate volume of literature for a comprehensive analysis.

Phase 3: Search strategies

The most common keywords in the scientific literature on the topic in question were identified using the UNESCO Thesaurus. Applying these keywords and different Boolean operators, the following search equation was established in the databases: (“opportunit*” OR “positive impact” OR “digital connection” OR “Internet” OR “digital competence*”) AND (“kid*” OR “young” OR “adolescent*” OR “preschool” OR “childhood education” OR “primary education” OR “secondary education”).

Phase 4: Selection process

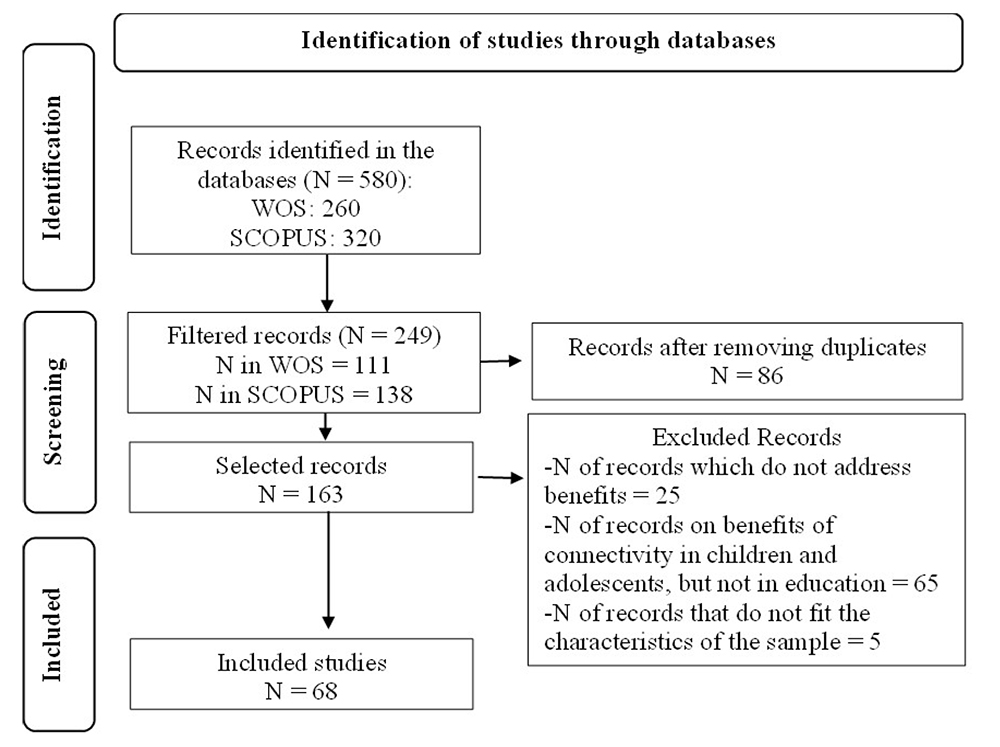

First, a total of 580 articles were identified using the search equation in both databases. After applying the eligibility criteria, the sample was reduced to 249 articles. Then 86 duplicates were detected between the two databases, reducing the sample to 163 articles. We proceeded to read the title and abstract, and if necessary the full article, to determine whether they were related to the subject of the review and to apply the exclusion criteria shown in Figure 1.

Results

The results of the systematic literature review are presented according to the areas identified and the research questions posed in each of them. This section cites the studies from the systematic literature review included in Annex 1.

Research area 1. Temporal evolution

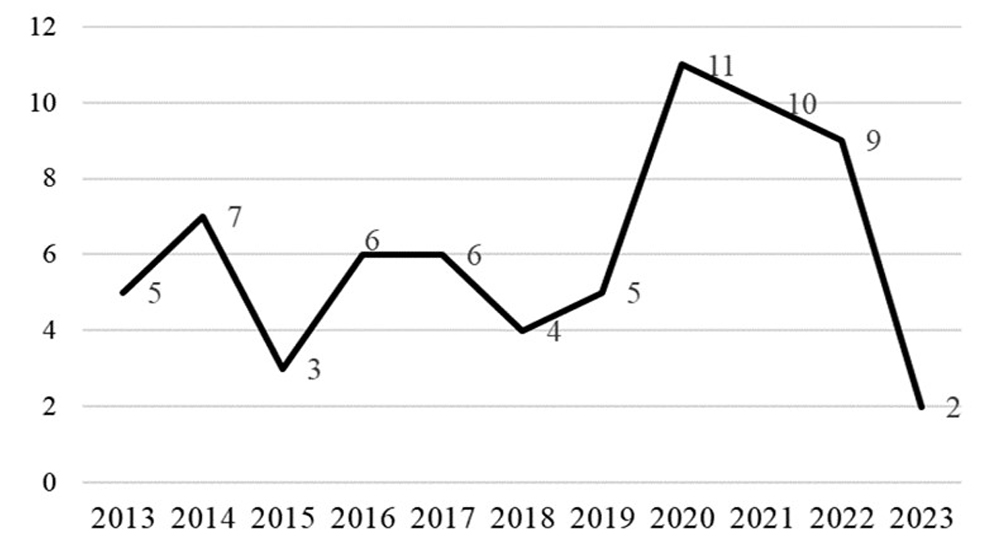

In response to Q1, studies on the use of digital connectivity in the education of children and adolescents have increased in recent years, as can be seen in Figure 2. The highest number of studies is reached in 2020.

Research area 2. Research methods

The research design of the analyzed works (Q2) was, to a greater extent, qualitative, with 45.5% of the cases (Domingo-Coscollola et al. 2018; Suparmi et al., 2020) and, to a lesser extent, quantitative, with 30.8% (Chou, 2017; Lin et al., 2017) and mixed, with 24% (Cohen Zilka, 2016; Gabarda et al., 2017). In response to Q3, most studies were based on evaluating the effects of an educational intervention, with 73.5% (Holguin-Álvarez et al., 2022; Leung et al., 2020).

Regarding the educational stage to which the participating children and adolescents belong (Q4), the number of studies in each of them is as follows: Early Childhood 0-5 years = 4 (Hollenstein et al., 2022; Vogt & Hollenstein, 2021); Primary6-11 years = 21 (Dunn & Sweeney, 2018; Kumpulainen et al., 2020); Secondary12-15 years = 20 (Gil Quintana & Osuna-Acebo, 2020; Yu et al., 2021); Postsecondary16-17 years = 5 (Mantilla Guiza & Negre Bennásar, 2021; Neagu et al., 2021); and various educational stages = 18 (Goodyear & Quennerstedt, 2020; Yelland, 2018). Consequently, the stages in which most studies concentrate are Primary and Secondary Education.

On the other hand, children and adolescents belonging to a vulnerable group (Q5) were considered in 36.7% of the cases. In response to Q6, these groups are functional diversity (Cranmer, 2020), ethnic-cultural diversity (Santos et al., 2015), high abilities (Suparmi et al., 2020), socioeconomic disadvantage (Cohen Zilka, 2016), rural areas (Ramoroka, 2014), underage women (Rillero et al., 2020), and intersectionality or various groups (Tuluk & Yurdugül, 2020).

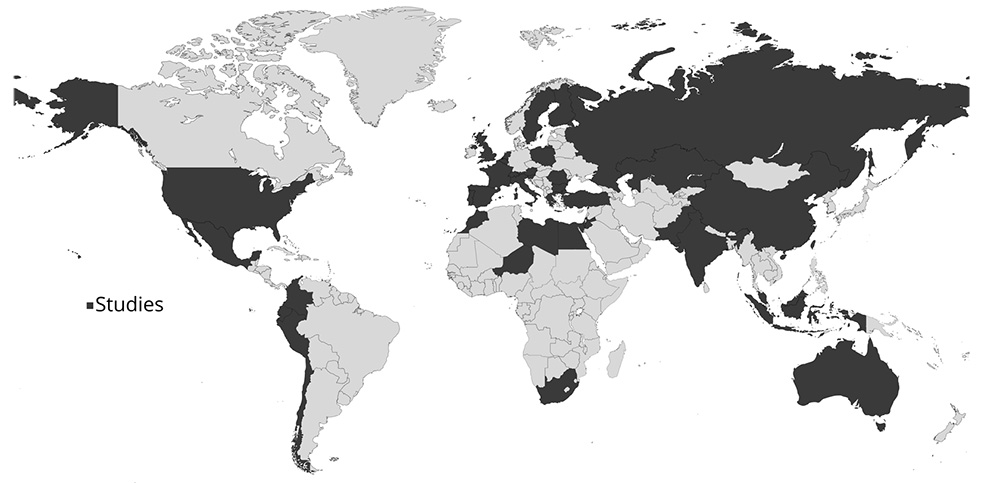

To respond to Q7 and provide a comprehensive view of the research on this topic, one observes that most of the articles (92%) refer to studies in which the participants are children and adolescents from a single country. Only in five studies are more than one country involved, notably that of Ranieri and Fabbro (2016), in which children and adolescents from seven European countries participate. In total, 78 countries are represented, as can be seen in Figure 3. In 54.4% of the studies, the participants are children and adolescents from European countries (Dias-Fonseca & Potter, 2016; Dunn & Sweeney, 2018), while in 19.1% belong to Asian countries (Lee, 2017; Leung et al., 2020), 13.2% to American countries (Armijo-Cabrera & Rojas, 2020; Jackson, 2022), 4.4% to African countries (Abimbola, 2013; Ramoroka, 2014), and only 2.8% to Oceania (McLean et al., 2016; Yelland, 2018). Within European countries, Spain is the country that reaches the highest number, with 11 published studies (Cuervo-Sánchez et al., 2022; Domingo-Coscollola et al., 2018). There are also studies that include countries from more than one continent, such as America and Africa (Rillero et al., 2020) and America and Europe (Tuzel and Hobbs, 2017).

Research area 3. Results obtained

The results obtained in the studies on the use of digital connectivity in the education of children and adolescents (Q8) have been distributed into six categories in relation to their use and these, in turn, according to whether there was a specific intervention to carry out the research.

1. Learning and improvement related to learning and improvement of specific subjects

The studies that highlight the benefits of connectivity in relation to the improvement of learning of subjects included in school curricula and learning in general, in which no specific intervention was carried out, emphasize that using of digital technologies and resources in the classroom favors both learning and digital competence. The study by García-Martín and García-Martín (2022) indicates that students perceive that this use supports their learning, although they are also aware that it can be distracting. Although González Vidal (2021) demonstrates the benefits of connectivity for academic performance in vulnerable students, Armijo-Cabrera and Rojas (2020) recommend that their exposure to the internet should be moderate and controlled by adults.

The appropriate use of social networks is beneficial since it increases students' informal learning and improves their motivation and digital competence, according to Gil Quintana and Osuna-Acebo (2020), Oliveira and Dias (2014) and Panskyi et al. (2021). Regarding the development of digital competence, Mantilla Guiza et al. (2021) show that it improves with the development of computational thinking and consequently improves the students' problem-solving ability.

Most of the studies found collected data after carrying out an intervention in the classroom that required digital technologies and resources. These studies highlight that the appropriate use of technologies in educational environments improves learning and students' own digital competence (García-Valcárcel et al., 2016; Magis-Weinberg et al., 2023), in addition to creativity (Sclater & Lally, 2014), due in part to the greater motivation of the students (Clarke & Abbott, 2016; Leinonen & Sintonen, 2014; Lin et al., 2017). Similarly, it was found that interventions in which social networks were used improved student learning in relation to health care, supporting habits such as sports or healthy eating (Goodyear et al., 2019; Goodyear & Quennerstedt, 2020). Even Badshah et al. (2021) demonstrated that the academic use of social networks by the entire educational community (students, teachers, and families) not only increases the academic performance of students, but also reduces school absenteeism.

Other results derived from the use of technologies in the classroom highlight the improvement of teacher-student communication and the promotion of student participation in activities (Santos Júnior et al., 2020), the interest in learning (Lee, 2017), or the improvement of writing skills (Dunn & Sweeney, 2018). As a nuance, Yelland (2018) states that using technologies in the classroom by itself does not improve learning and that their use should complement traditional methodologies. It was found to be equally beneficial for the learning of students belonging to vulnerable groups, such as students with high abilities (Abakumova et al., 2019), students living in rural areas (Ramoroka, 2014), visually impaired (Cranmer, 2019), or with limited economic resources (Solórzano Alcívar et al., 2022).

Some of the analyzed articles place value on the appropriate use of technology and connectivity to improve academic performance in curricular subjects such as English (Abimbola, 2013; García-Valcárcel et al., 2016; Toleuzhan et al., 2023), History (Kotsira et al., 2021), Biology (Rillero et al., 2020), Mathematics (Al-Mashaqbeh, 2016; Hrastinski & Stenbom, 2013; Holguin-Alvarez et al., 2022; Tuluk & Yurdugül, 2020;), Science (Chou, 2017), Language (Santos Júnior et al., 2020), Music (Romero Martínez & Vela Barranco, 2014), or STEAM competencies from Primary Education (Kumpulainen et al., 2020).

2. Advantages of connectivity to digital inclusion and accessibility and the fight against exclusion or digital divide

Children and young people's connectivity is analyzed in several studies that report advantages to overcoming challenges of digital exclusion, reducing the digital divide and promoting inclusion in the digital sphere. In the studies in which there was no specific intervention in the classroom, it was found that students belonging to disadvantaged groups who have the opportunity to use the internet appropriately overcome barriers related to digital exclusion (Álvarez-Guerrero et al. 2021; Neagu et al., 2021; Pathak-Shelat & DeShano, 2014; Simões et al., 2013) significantly when taking advantage of the possibility to communicate with others afforded by social media (Vasco-González et al., 2021).

These benefits that allow the digital inclusion of children and young people have also been found in research comprising classroom interventions. Cohen Zilka (2016) concluded that connectivity originating from the classroom reduces the digital divide for youngsters. Wong and Kemp (2018) also verified that this connectivity supported by teachers can reduce the digital gender gap.

3. Advantages of digital creation and production

The papers we analyzed that looked at the possibilities of creating and producing their own digital content conclude that it has multiple benefits for children. All of the papers in this sub-section carried out a classroom intervention in which the students had digital resources for their own creation. The improved expansion of children's creativity was evident in different educational stages in the work of Suparmi et al. (2020).

Specifically, interventions that proposed the design of collaborative video games in the classroom found improvements in children's digital competences (Laakso et al., 2021), in raising awareness about social and social justice issues (Jackson, 2022), and in creativity and critical thinking (Behnamnia et al., 2020; Leung et al., 2020). Advantages were also found in creating digital applications (Hollenstein et al., 2022) and group blogs (Goedhart et al., 2022).

The experiments based on the Do-it-Yourself (DIY) culture collaboratively using digital resources stand out among the studies in this sub-section. This type of experiment improved the digital competence, creativity, and self-regulation of the students (Domingo-Coscollola et al., 2018); and Kumpulainen and Kajamaa (2020) claim that the use of “maker spaces” acts as a privileged space to create and develop the interest, collaboration, and empowerment of students.

4. Advantages for the development of collaboration skills

Several studies identified significant advantages from digital connectivity in promoting skills related to collaboration. All had carried out a classroom intervention and reported improvements in communication, collaborative work skills (Santos Júnior et al., 2020), and shared responsibility in learning (Sjöberg & Brooks, 2020). In studies comprising playing a collaborative online game, Shiue and Hsu (2017), Vogt and Hollenstein (2021), and Khouna et al. (2019) found that collaboration and communication, creativity, critical thinking, motivation, and commitment in learning improved.

5. Advantages resulting from the participation in specific media and digital education programs

Training programs focused on leveraging connectivity among children are addressed in the part of the analyzed research, highlighting multiple advantages. Wernholm and Reneland-Forsman (2019) suggest that programs focused on the appropriate use of social media favor the construction of their digital identity.

All the studies included in this category that carried out an educational intervention agree in putting forward a firm commitment to the inclusion of these programs (Cuervo-Sánchez et al., 2022; Dias-Fonseca & Potter, 2016; Martens & Hobbs, 2015; Rillero et al., 2020; Tuzel & Hobbs, 2017), reporting improvement in the students' intercultural communication, in their civic engagement (Hobbs et al., 2013), in the empowerment of vulnerable young people (Santos et al., 2015), in preventing the incorrect influence of the media on teenagers' identities (McLean et al., 2016), or in the development of skills to prevent and fight online discrimination (Ranieri & Fabbro, 2016). However, it must be considered that the authors emphasize the need for teacher training in this area for the programs to be effective.

6. Advantages of connectivity in emergencies (pandemic)

The closure of educational centers because of the COVID-19 pandemic led to new forms of online learning, with positive effects on students, who developed their digital skills (Panskyi et al., 2021) and learning in general (Yu et al., 2021). The intervention proposed by Álvarez-Guerrero et al. (2021) allowed the continuity of learning among students with functional diversity.

Research area 4. Implications for educational research and practice

Responding to Q9, we found that several studies recommend taking advantage of students' critical capacity regarding the media content they consume to undertake social change through education (Espinosa-Bayal et al., 2014; Vasco-González et al., 2021), use the opportunities provided by the internet in classrooms within a training plan (Tarango Ortiz et al., 2014), and consider the positive impact of the use of social media in rural contexts or with socioeconomic disadvantage (Badshah et al., 2021).

Leinonen and Sintonen (2014) highlight the need to promote media education from an early age to prevent risks and take advantage of the opportunities of the internet, and Gabarda et al. (2017) demand specific training plans aimed at students, teachers, and families. Likewise, the potential of virtual contexts to motivate learning for both students with high abilities (Abakumova et al., 2019) and those with low academic performance (Chou, 2017) is highlighted. The possibilities of personalizing teaching-learning through individual devices are also highlighted (Al-Mashaqbeh, 2016).

There are publications that value action research to analyze student behavior (Domingo-Coscollola et al., 2018), gamification to promote pedagogical practices based on immersion for language learning (Santos Júnior et al., 2020), and videogames in general as elements of motivation (Sjöberg & Brooks, 2020; Jalal et al., 2019; Goodyear & Quennerstedt, 2020), teacher training to encourage the use of digital games (Hollestein et al., 2022), and teaching communities to exchange experiences on digital learning (Lin et al., 2017). We could find replicable contributions from pedagogical models along these lines (Cuervo-Sánchez et al., 2022).

As secondary implications, it should be noted that when researching the impact of digitalization in education, not only access should be valued, but also the actual use and literacy of students (García-Valcárcel et al., 2016; Pathak-Shelat and DeShano, 2014; Simões et al., 2013)

Research area 5. Future lines of research

Lastly, in answering Q10 and looking out for the potential of technologies to develop opportunities in the educational field, the analyzed papers still propose new research that gets a more profound knowledge about some of the aspects that have already begun to be explored. Thus, a deeper analysis is suggested on digital educational practices in language learning (Santos Júnior et al., 2020), the collaborative design of digital games (Laakso et al., 2021), the integration of augmented reality in education (Kotsira et al. 2021), the use of blogs as an educational tool (Romero Martínez & Vela Barranco, 2014), or game-based learning and gamification (Shiue & Hsu, 2017; Tuluk & Yurdugül, 2020).

The interest in continuing to delve into the possibilities of online assessment is highlighted (Lee, 2017), as into the development of learning opportunities in the virtual context aimed at students with functional diversity (Álvarez-Guerrero et al., 2021) or initiatives that seek to reduce the digital gender gap (Wong & Kemp, 2018) and digital exclusion (Simões et al., 2013).

Similarly, longitudinal studies are proposed to understand possible changes in trends (García-Martín & García-Martín, 2022) and overcome particularities linked to the pandemic (Panskyi et al., 2022) or expand work carried out in specific populations, such as first childhood (Hollenstein et al., 2022).

Likewise, some authors suggest expanding the focus of analysis to other agents within educational ecosystems. Thus, studies are proposed that include the perspective of the teachers and the management teams of the centers (García-Martín & García-Martín, 2022).

Discussion and conclusions

This article offers a systematic review of the literature on the advantages of digital connectivity in the education of children and young people based on the analysis of 68 studies published in the last decade.

Regarding the first research area, the results show how, in recent years, studies on the use of digital connectivity in the education of children and youth have increased. This represents progress in this object of study if we remind that, at the beginning of the century, research was limited exclusively to computers, considered as secondary objects in the educational process (Stephen & Plowman, 2003) and, later, to the prevention of risks as a predominant approach (Orben, 2020)

The second area of this review focused on understanding the research methodologies deployed. The results show the prevalence of qualitative designs that seek to evaluate the effects of an educational intervention, particularly those in which the participants are European, are in the Primary and Secondary Education levels, and include vulnerable groups in a third of the cases. These findings differ from the results obtained in the review by Miller et al. (2017), which concluded that the predominant methodology is based on mixed designs and survey methods for data collection, and that the samples are homogeneous. However, our findings do agree with the review by Miller et al. in which learning tasks and social interactions are taken as study variables.

The third area of research addresses the central objective of this review. It is concluded that digital connectivity is beneficial for children and young people if it is linked to learning and improving the subject matters, digital inclusion and accessibility, digital creation and production, collaborative learning, and media and digital education. This finding supports previous research which demonstrated the educational use of connectivity associated with: access to educational information and resources (Salmerón et al., 2018), the personalization of learning to improve educational quality (Panjaburee et al., 2022), collaboration between students and interactive learning (Sahronih et al., 2019), promoting creativity and content production (Marsh et al., 2018), and creating a more inclusive and equitable learning environment (Parmigiani et al., 2021).

Per the fourth area, the studies in this review stress the need for media education and the development of critical thinking from an early age to prevent risks and leverage the opportunities of the internet. This is in line with UNESCO's strategy (2021) based on taking advantage of connectivity and risk prevention in developing of the right to education. Indeed, they emphasize the possibilities of personalizing teaching-learning through technological devices, considering different situations of vulnerability of students. All of them are implications for educational practice, which can be implemented in teaching innovations for which teachers must be trained (Fernández-Batanero et al., 2022). Implications for research are also raised, such as studying the actual use and positive impact of digital connectivity on children and young people due to media literacy.

Furthermore, the last area of research gives an account of the future lines proposed by the analyzed articles, which suggests continuing investigating educational practices to take advantage of connectivity. This is in line with the review by Belo et al. (2016), which proposes to study the impact of digital activities on learning, and with that of Mantilla et al. (2019), which suggests investigating effective strategies to teach digital skills.

Regarding this study's limitations, it should be noted that only two databases were considered. Although both have broad reach and recognition in the academic community, for future research we suggest including other complementary indexing systems that may contain more articles related to this topic. In this regard, a broader comparative vision is proposed that integrates the rest of the agents of the educational community, such as teachers, management teams and families, or groups of students above 18 years old.

REFERENCES

Belo, N., McKenney, S., Voogt, J., y Bradley, B. (2016). Teacher knowledge for using technology to foster early literacy: A literature review. Computers in Human Behavior, 60, 372-383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.053 [ Links ]

Fernández-Batanero, J. M., Montenegro-Rueda, M, Fernánfez-Cerero, J, García-MartínezI. (2022). Digital competences for teacher professional development. Systematic review. European Journal of Teacher Education, 45(4), 513-531. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1827389 [ Links ]

García-Hernández, A., García-Valcárcel Muñoz-Repiso, A., Casillas-Martín, S., y Cabezas-González, M. (2023). Sustainability in digital education: A systematic review of innovative proposals. Education Sciences, 13(1), Artículo 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010033 [ Links ]

Ihmeideh, F., y Alkhawaldeh, M. (2017). Teachers' and parents' perceptions of the role of technology and digital media in developing child culture in the early years. Children and Youth Service Review, 77, 139-146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.04.013 [ Links ]

Kalolo, J. F. (2019). Digital revolution and its impact on education systems in developing countries. Education and Information Technologies, 24, 345-358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-018-9778-3 [ Links ]

Mantilla, A., y Edwards, S. (2019). Digital technology use by and with young children: A systematic review for the Statement on Young Children and Digital Technologies. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 44(2), 182-195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1836939119832744 [ Links ]

Marsh, J., Plowman, L., Yamada-Rice, D., Bishop, J., Lahmar, J., y Scott, F. (2018). Play and creativity in young children's use of apps. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(5), 870-882. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12622 [ Links ]

Miller, J. L., Paciga, K. A., Danby, S., Beaudoin-Ryan, L., y Kaldor, T. (2017). Looking beyond swiping and tapping: Review of design and methodologies for researching young children's use of digital technologies. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 11(3), Artículo 6. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2017-3-6 [ Links ]

Orben, A. (2020). Teenagers, screens and social media: A narrative review of reviews and key studies. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55, 407-414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01825-4 [ Links ]

Panjaburee, P., Komalawardhana, N., y Ingkavara, T. (2022). Acceptance of personalized e-learning systems: A case study of concept-effect relationship approach on science, technology, and mathematics courses. Journal of Computers in Education, 9, 681-705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-021-00216-6 [ Links ]

Parmigiani, D., Benigno, V., Giusto, M., Silvaggio, C., y Sperandio, S. (2020). E-inclusion: Online special education in Italy during the Covid-19 pandemic. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 30(1), 111-124. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2020.1856714 [ Links ]

Romera, E. M., Camacho, A., Ortega-Ruiz, R., y Falla, D. (2021). Cibercotilleo, ciberagresión, uso problemático de Internet y comunicación con la familia. Comunicar, 67, 61-71. https://doi.org/10.3916/C67-2021-05 [ Links ]

Sahronih, S., Purwanto, A., y Sumantri, M. S. (2019). The effect of interactive learning media on student' science learning outcomes. En Association for Computing Machinery. ICIET 2019: Proceedings of the 2019 7th International Conference on Information and Education Technology (pp. 20-24). https://doi.org/10.1145/3323771.3323797 [ Links ]

Salmerón, L., García, A., y Vidal-Abarca, E. (2018). The development of adolescents' comprehension-based Internet reading activities. Learning and Individual Differences, 61, 31-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.11.006 [ Links ]

Sánchez-Serrano, S., Pedraza-Navarro, I. y Donoso-González, M. (2022). ¿Cómo hacer una revisión sistemática siguiendo el protocolo PRISMA? Usos y estrategias fundamentales para su aplicación en el ámbito educativo a través de un caso práctico. Bordón, 74(3), 51-66. https://doi.org/10.13042/Bordon.2022.95090 [ Links ]

Stephen, C., y Plowman, L. (2003). Information and communication technologies in pre-school settings: A review of the literature. International Journal of Early Years Education, 11(3), 223-234. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966976032000147343 [ Links ]

Timotheou, S., Miliou, O., Dimitriadis, Y., Villagrá Sobrino, S., Giannoutsou, R. C., Martínez Monés, A., y Ioannou, A. (2022). Impacts of digital technologies on education and factors influencing schools' digital capacity and transformation: A literature review. Education and Information Technologies , 28, 6695-6726. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11431-8 [ Links ]

UNESCO (2021). Rewired Global Declaration on Connectivity for Education. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000381482.locale=en [ Links ]

Van Endert, T. S. (2021). Addictive use of digital devices in young children: Associations with delay discounting, self-control and academic performance. PLoS ONE, 16(6), Artículo e0253058. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253058 [ Links ]

Vidal-Hall, C., Flewitt, R., y Wyse, D. (2020). Early childhood practitioner beliefs about digital media: Integrating technology into a child-centred classroom environment. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 28(2), 167-181. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2020.1735727 [ Links ]

Abakumova, I., Bakaeva, I., Grishina, A., y Dyakova, E. (2019). Active learning technologies in distance education of gifted students. International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science Engineering and Education, 7(1), 85-94. https://doi.org/10.5937/IJCRSEE1901085A [ Links ]

Abimbola, O. (2013). Towards the integration of mobile phones in the teaching of English language in secondary schools in Akure, Nigeria. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 3(7), 1149-1153. https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.3.7.1149-1153 [ Links ]

Al-Mashaqbeh, I. F. (2016). IPad in elementary school Math learning setting. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 11(02), 48. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v11i02.5053 [ Links ]

Álvarez-Guerrero, G., López de Aguileta, A., Racionero-Plaza, S., y Flores-Moncada, L. G. (2021). Beyond the school walls: Keeping interactive learning environments alive in confinement for students in special education. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.662646 [ Links ]

Armijo-Cabrera, M., y Rojas, M.T. (2020). Virtualidad y cultura digital en las experiencias escolares infantiles: Una etnografía visual en contexto de pobreza. Pensamiento Educativo, 57(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.7764/PEL.57.1.2020.8 [ Links ]

Badshah, A., Jalal, A., Rehman, G. U., Zubair, M., y Umar, M. M. (2021). Academic use of social networking sites in learners' engagement in underdeveloped countries' schools. Education and Information Technologies, 26(5), 6319-6336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10619-8 [ Links ]

Behnamnia, N., Kamsin, A., Ismail, M. A. B., y Hayati, A. (2020). The effective components of creativity in digital game-based learning among young children: A case study. Children and Youth Services Review, 116, Artículo 105227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105227 [ Links ]

Chou, C. C. (2017). An analysis of the 3D video and interactive response approach effects on the science remedial teaching for fourth grade underachieving students. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 13(4), 1059-1073. https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2017.00658a [ Links ]

Clarke, L., y Abbott, L. (2016). Young pupils', their teacher's and classroom assistants' experiences of iPads in a Northern Ireland school: “Four and five years old, who would have thought they could do that?”. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(6), 1051-1064. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12266 [ Links ]

Cohen Zilka, G. (2016). Reducing the digital divide among children who received desktop or hybrid computers for the home. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 15, 233-251. https://doi.org/10.28945/3519 [ Links ]

Cranmer, S. (2020). Disabled children's evolving digital use practices to support formal learning. A missed opportunity for inclusion. British Journal of Educational Technology , 51(2), 315-330. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12827 [ Links ]

Cuervo-Sánchez, S. L., Martínez-de-Morentin, J. I., y Medrano-Samaniego, C. (2022). Una intervención para mejorar la competencia mediática e informacional. Educación XX1, 25(1), 407-431. https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.30364 [ Links ]

Dias-Fonseca, T., y Potter, J. (2016). Media education as a strategy for online civic participation in Portuguese schools. Comunicar, 24(49), 9-18. https://doi.org/10.3916/C49-2016-01 [ Links ]

Domingo-Coscollola, M., Onsés Segarra, J., y Sancho Gil, J. M. (2018). La cultura DIY en Educación Primaria. Aprendizaje transdisciplinar, colaborativo y compartido en DIYLabHub. Universidad de Murcia Servicio de Publicaciones. https://digitum.um.es/digitum/handle/10201/75641 [ Links ]

Dunn, J., y Sweeney, T. (2018). Writing and iPads in the early years: Perspectives from within the classroom. British Journal of Educational Technology , 49(5), 859-869. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12621 [ Links ]

Espinosa-Bayal, M. Á., Ochaíta-Alderete, E., y Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, H. (2014). Adolescent television consumers: Self-perceptions about their rights. Comunicar, 22(43), 181-188. https://doi.org/10.3916/C43-2014-18 [ Links ]

Gabarda, S., Orellana Alonso, N., y Pérez Carbonell, A. (2017). La comunicación adolescente en el mundo virtual: Una experiencia de investigación educativa. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 35(1), 251-267. https://doi.org/10.6018/rie.35.1.251171 [ Links ]

García-Martín, S., y García-Martín, J. (2022). Uso de las TIC en Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Ventajas e inconvenientes. Revista Internacional de Humanidades, 11, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.37467/revhuman.v11.3965 [ Links ]

García-Valcárcel, A., Basilotta, V., y Mulas, I. (2016). Fomentando la ciudadanía digital mediante un proyecto de aprendizaje colaborativo entre escuelas rurales y urbanas para aprender inglés. Profesorado, 20(3), 549-581. [ Links ]

Gil Quintana, J., y Osuna-Acedo, S. (2020). Transmedia practices and collaborative strategies in informal learning of adolescents. Social Sciences, 9(6), Artículo 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9060092 [ Links ]

Goedhart, N. S., Lems, E., Zuiderent-Jerak, T., Pittens, C. A. C. M., Broerse, J. E. W., y Dedding, C. (2022). Fun, engaging and easily shareable? Exploring the value of co-creating vlogs with citizens from disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Action Research, 20(1), 56-76. https://doi.org/10.1177/14767503211044011 [ Links ]

González Vidal, I. M. (2021). Influencia de las TIC en el rendimiento escolar de estudiantes vulnerables. RIED Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 24(1), 351-365. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.24.1.27960 [ Links ]

Goodyear, V. A., Armour, K. M., y Wood, H. (2019). Young people and their engagement with health-related social media: New perspectives. Sport, Education and Society, 24(7), 673-688. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2017.1423464 [ Links ]

Goodyear, V., y Quennerstedt, M. (2020). #Gymlad - Young boys learning processes and health-related social media. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 12(1), 18-33. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1673470 [ Links ]

Hobbs, R., Donnelly, K., Friesem, J., y Moen, M. (2013). Learning to engage: How positive attitudes about the news, media literacy, and video production contribute to adolescent civic engagement. Educational Media International, 50(4), 231-246. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2013.862364 [ Links ]

Holguin-Alvarez, J., Apaza-Quispe, J., Cruz-Montero, J., Ruiz Salazar, J. M., y Huaita Acha, D. M. (2022). Gamificación mixta con videojuegos y plataformas educativas: Un estudio sobre la demanda cognitiva matemática. Digital Education Review, 42, 136-153. https://doi.org/10.1344/der.2022.42.136-153 [ Links ]

Hollenstein, L., Thurnheer, S., y Vogt, F. (2022). Problem solving and digital transformation: Acquiring skills through pretend play in kindergarten. Education Sciences, 12(2), Artículo 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12020092 [ Links ]

Hrastinski, S., y Stenbom, S. (2013). Student-student online coaching: Conceptualizing an emerging learning activity. The Internet and Higher Education, 16, 66-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2012.02.003 [ Links ]

Jackson, R. (2022). Collaborative video game design as an act of social justice. Studies in Art Education, 63(2), 134-151. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393541.2022.2050985 [ Links ]

Jalal, K., Lotfi, A., Ahmed, R., y Abdelilah, E. M. (2019). Are educational games engaging and motivating Moroccan students to learn physics? International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 14(16), 66-82. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v14i16.10641 [ Links ]

Kotsira, M., Ntalianis, K., Kikili, V., Ntalianis, F., y Mastorakis, N. (2021). New technologies in the instruction of History in primary education. International Journal of Education and Information Technologies , 15, 21-27. https://doi.org/10.46300/9109.2021.15.3 [ Links ]

Kumpulainen, K., y Kajamaa, A. (2020). Sociomaterial movements of students' engagement in a school's makerspace. British Journal of Educational Technology , 51(4), 1292-1307. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12932 [ Links ]

Kumpulainen, K., Kajamaa, A., Leskinen, J., Byman, J., y Renlund, J. (2020). Mapping digital competence: students' maker literacies in a school's makerspace. Frontiers in Education, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.00069 [ Links ]

Laakso, N. L., Korhonen, T. S., y Hakkarainen, K. P. J. (2021). Developing students' digital competences through collaborative game design. Computers y Education, 174, Artículo 104308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104308 [ Links ]

Lee, C. I. (2017). Assigning the appropriate works for review on networked peer assessment. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education , 13(7), 3283-3300. https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2017.00717a [ Links ]

Leinonen, J., y Sintonen, S. (2014). Productive participation - Children as active media producers in kindergarten. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 9(3), 216-236. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1891-943X-2014-03-04 [ Links ]

Leung, S. K. Y., Choi, K. W. Y., y Yuen, M. (2020). Video art as digital play for young children. British Journal of Educational Technology , 51(2), 531-554. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12877 [ Links ]

Lin, M. H., Chen, H. C., y Liu, K. S. (2017). A study of the effects of digital learning on learning motivation and learning outcome. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education , 13(7), 3553-3564. https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2017.00744a [ Links ]

Magis-Weinberg, L., Muñoz Lopez, D. E., Gys, C. L., Berger, E. L., y Dahl, R. E. (2023). Promoting digital citizenship through a school-based intervention in early adolescence in Perú (a pilot quasi-experimental study). Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 28(1), 83-89. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12625 [ Links ]

Mantilla Guiza, R. R., y Negre Bennásar, F. (2021). Pensamiento computacional: Una estrategia educativa en épocas de pandemia. Innoeduca: International Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation, 7(1), 89-106. [ Links ]

Martens, H., y Hobbs, R. (2013). How media literacy supports civic engagement in a digital age. Communication Studies Faculty Publications, 23(2), 120-137. https://doi.org/10.1080/15456870.2014.961636 [ Links ]

McLean, S. A., Paxton, S. J., y Wertheim, E. H. (2016). Does media literacy mitigate risk for reduced body satisfaction following exposure to thin-ideal media? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(8), 1678-1695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0440-3 [ Links ]

Neagu, G., Berigel, M., y Lendzhova, V. (2021). How digital inclusion increase opportunities for young people: case of NEETs from Bulgaria, Romania and Turkey. Sustainability, 13(14), Artículo 7894. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147894 [ Links ]

Oliveira, A., y Dias, R. (2014). With or without a computer? Do you want to play with me? Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences , 5(13), 21-28. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n13p21 [ Links ]

Panskyi, T., Korzeniewska, E., Serwach, M., y Grudzień, K. (2022). New realities for Polish primary school informatics education affected by COVID-19. Education and Information Technologies , 27(4), 5005-5032. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10778-8 [ Links ]

Pathak-Shelat, M., y DeShano, C. (2014). Digital youth cultures in small town and rural Gujarat, India. New Media & Society, 16(6), 983-1001. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813496611 [ Links ]

Ramoroka, T. (2014). Wireless internet connection for teaching and learning in rural schools of South Africa: The University of Limpopo TV White Space Trial Project. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences , 5(15), 381-385. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n15p381 [ Links ]

Ranieri, M., y Fabbro, F. (2016). Questioning discrimination through critical media literacy. Findings from seven European countries. European Educational Research Journal, 15(4), 462-479. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904116629685 [ Links ]

Rillero, P., Soykal, A. K., y Bicer, A. (2020). Virtual exchange with problem-based learning: Practicing analogy development with diverse partners. The American Biology Teacher, 82(7), 447-452. https://doi.org/10.1525/abt.2020.82.7.447 [ Links ]

Romero Martínez, S., y Vela Barranco, M. (2014). Edublogs musicales en el tercer ciclo de educación primaria: Perspectiva de alumnos y profesores. Revista Complutense de Educación, 25(1), 195-221. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_RCED.2014.v25.n1.41351 [ Links ]

Santos Júnior, G. P., Escudeiro, P., Moura, A., y Lucena, S. (2020). Gamificação e os dispositivos digitais no ensino secundário em Braga, Portugal. Práxis Educacional, 16(41), 278-298. https://doi.org/10.22481/praxisedu.v16i41.7264 [ Links ]

Santos, S., Brites, M. J., Jorge, A., Catalão, D., y Navio, C. (2015). Learning for life: A case study on the development of online community radio. Cuadernos.Info, 36, 111-123. http://dx.doi.org/10.7764/cdi.36.610. [ Links ]

Sclater, M., y Lally, V. (2014). The realities of researching alongside virtual youth in late modernity creative practices and activity theory. Journal of Youth Studies, 17(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2013.847908 [ Links ]

Shiue, Y. M., y Hsu, Y. C. (2017). Understanding factors that affecting continuance usage intention of game-based learning in the context of collaborative learning. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education , 13(10), 6445-6455. https://doi.org/10.12973/ejmste/77949 [ Links ]

Simões, J. A., Ponte, C., y Jorge, A. (2013). Online experiences of socially disadvantaged children and young people in Portugal. Communications - The European Journal of Communication Research, 38(1), 85-106. https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2013-0005 [ Links ]

Sjöberg, J., y Brooks, E. (2020). Problem solving and collaboration when school children develop game designs. En A. Brooks y E.I. Brooks (Eds.), Interactivity, Game Creation, Design, Learning, and Innovation (pp. 683-698). Springer. [ Links ]

Solórzano Alcívar, N., Quinto Veloz, K., Valarezo Risso, S., y Elizalde Ríos, E. (2022). MIDI-AM, serious games for children as supporting tools in educational virtuality for marginal areas of high vulnerability. En Latin American and Caribbean Consortium of Engineering Institutions Proceedings of the 20th LACCEI International Multi-Conference for Engineering, Education and Technology: “Education, Research and Leadership in Post-Pandemic Engineering: Resilient, Inclusive and Sustainable Actions”. https://doi.org/10.18687/LACCEI2022.1.1.500 [ Links ]

Suparmi, P, Suardiman S. P. , BudiningsihC. A . (2020). The pupil's creativity is inspired by experience through electronic media: Empirical study in Yogyakarta. International Journal of Instruction, 13(2), 637-648. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2020.13243a [ Links ]

Tarango Ortiz, J., Romo González, J. R., Murguía Jáquez, P., y Ascencio Baca, G. (2014). Uso y acceso a las TIC en estudiantes de escuelas secundarias públicas en la ciudad de Chihuahua, México: Inclusión en la didáctica y en la alfabetización digital. Revista Complutense de Educación , 25(1), 133-152. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_RCED.2014.v25.n1.41250 [ Links ]

Toleuzhan, A., Sarzhanova, G., Romanenko, S., Uteubayeva, E., y Karbozova, G. (2023). The educational use of Youtube videos in communication fluency development in English: Digital learning and oral skills in Secondary Education. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology, 11(1), 198-221. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijemst.2983 [ Links ]

Tuluk, A., y Yurdugül, H. (2020). Design and development of a web based dynamic assessment system to increase students' learning effectiveness. International Journal of Assessment Tools in Education, 7(4), 631-656. https://doi.org/10.21449/ijate.730454 [ Links ]

Tuzel, S., y Hobbs, R. (2017). the use of social media and popular culture to advance cross-cultural understanding. Comunicar, 25(1), 63-72. https://doi.org/10.3916/C51-2017-06 [ Links ]

Vasco-González, M., Goig-Martínez, R. M., Martínez-Sánchez, I., y Álvarez-Rodríguez, J. (2021). Socially disadvantaged youth: Forms of expression and communication in social networks as a vehicle of inclusion. Sustainability, 13(23), Artículo 13160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313160 [ Links ]

Vogt, F., y Hollenstein, L. (2021). Exploring digital transformation through pretend play in kindergarten. British Journal of Educational Technology , 52(6), 2130-2144. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13142 [ Links ]

Wernholm, M., y Reneland-Forsman, L. (2019). Children's representation of self in social media communities. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 23, Artículo 100346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2019.100346 [ Links ]

Wong, B., y Kemp, P. E. J. (2018). Technical boys and creative girls: The career aspirations of digitally skilled youths. Cambridge Journal of Education, 48(3), 301-316. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2017.1325443 [ Links ]

Yelland, N. J. (2018). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Young children and multimodal learning with tablets. British Journal of Educational Technology , 49(5), 847-858. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12635 [ Links ]

Yu, L., Lan, M., y Xie, M. (2021). The survey about live broadcast teaching in Chinese middle schools during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Education and Information Technologies , 26(6), 7435-7449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10610-3 [ Links ]

Funding This work has been funded by the Department of Universities, Equality, Culture and Sports of the Government of Cantabria, in support of the R&D project “Media and digital literacy in young people and adolescents: diagnosis and educational innovation strategies to prevent risks and promote good practices on the Internet” (2022-23).

Received: May 17, 2023; Revised: September 06, 2023; Accepted: October 11, 2023

texto en

texto en