Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

The European Journal of Psychiatry

versión impresa ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.30 no.1 Zaragoza ene./mar. 2016

Insight assessment in psychosis and psychopathological correlates: Validation of the Spanish version of the Schedule for Assessment of Insight - Expanded Version

Juan Soriano-Barcelóa, MD; Javier D. López-Moríñigob, MD; Ramón Ramos-Ríosa, MD; E. Alonso Rodríguez-Zanabriac, MD and Anthony S. Davidb, MD, FRCP, FRCPsych

a Psychiatry Department, University. Complex Hospital of Santiago de Compostela. Travesia da Choupana, s/n. 15706. Santiago de Compostela. (A Coruña, Spain).

b Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London. PO-Box 63-Institute of Psychiatry. De Crespigny Park. SE5 7BE. London (United Kingdom).

c St. John of God Psychiatric Hospital, "Centro de Reposo de Enfermos Mentales de Piura y Talara", C/ Cayetano Heredia. s/n, Piura (Peru)

JDLM and ASD are supported by the National Institute of Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the South London & Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and the Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, UK. JDLM also acknowledges funding support from the British Medical Association via the Margaret Temple Grant for schizophrenia.

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives: Lack of insight is a cardinal feature of psychosis. Insight has been found to be a multidimensional concept, including awareness of having a mental illness, ability to relabel psychotic phenomena as abnormal and compliance with treatment., which can be measured with the Schedule for Assessment of Insight (SAI-E). The aim of this study was to validate the Spanish version of SAI-E.

Methods: The SAI-E was translated into Spanish and back-translated into English, which was deemed appropriate by the original scale author. Next, the Spanish version of the SAI-E was administered to 39 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (DSM-IV criteria) from a North Peruvian psychiatric hospital. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for Schizophrenia (PANSS) and the Scale of Unawareness of Mental Disorder (SUMD) were also administered. Specifically, internal consistency and convergent validity were assessed.

Results: Internal consistency between the 11 items of the SAI-E was found to be good to excellent (α = 0.942). Compliance items did not contribute to internal consistency (A = 0.417, B = 572). Inter-rater reliability was excellent (ICC = 0.99). Regarding concurrent validity, the SAI-E total score correlated negatively with the lack of insight and judgement item of the PANNS (r = -0.91, p <0.01) and positively with the SUMD total score (r = 0.92, p <0.001).

Conclusions: The Spanish version of the SAI-E scale was demonstrated to have both excellent reliability and external validity in our sample of South American Spanish-speaking patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

Key words: Insight; Psychosis; SAI-E; Validation; Spanish; Psychometrics.

Introduction

Lack of insight has been considered a cardinal feature of psychotic disorders, particularly schizophrenia1. Lack of insight in psychosis is also associated with greater psychopathological severity, poorer psychosocial functioning, longer duration of untreated psychosis2,3, poorer compliance, increased readmissions, especially compulsorily4, and overall, with a poorer prognosis4,6.Over the last 20 years, a multidimensional model of insight has been consistently replicated7-9. In particular, in 1990 David proposed three different, albeit related, dimensions: awareness of having a mental illness, treatment compliance, and the ability to characterize previous psychotic symptoms as pathological. Amador (1993) distinguished awareness from attribution10,11 and emphasized awareness of the social consequences of the illness6.

However, the mechanisms underlying lack of insight in psychosis remain unknown, although psychological12, psychopathological13 and neuropsychological14 theories have been proposed, including the role of cultural factors15,16.

With regard to neurocognitive deficits, both general cognition and executive function impairments have been linked to poor insight in schizophrenia14. Of note, these cognitive deficits appear to precede the onset of psychosis17.

From a psychodynamic perspective, lack of insight has been considered to be a denial mechanism which might protect patient self-esteem18. This may be supported by the known association between insight and severity of depressive symptoms19, although the role of insight in suicidal risk remains unclear20. Both negative and positive symptoms severity has been associated with impaired insight. However, depressive symptoms were found to have a positive relationship with insight22,23.

Hence, insight assessment seems to have crucial implications on patient management.

Thus, several scales have been validated for the multidimensional assessment of insight: the Insight and Treatment Attitudes Questionnaire (ITAQ)11, the Schedule for the Assessment of Insight (SAI)9 and extended version (SAI-E)24, the Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder (SUMD)10, and the Birchwood Self-report Insight Scale (IS)25. These scales showed high levels of correlation, hence insight can be measured in spite of its conceptual complexity26.

The expanded version of SAI9, the SAI-E24 is a semi-structured interview used to measure three insight dimensions in accordance with David's model9. This scale has been validated in several languages, including Greek4, Portuguese27 and Arabic28, Tamil29 and Mandarin (ref) (among others)4,27-29. Although no SAI-E Spanish version has been validated to date, the Scale of Unawareness of Mental Disorder (SUMD)10 had been validated in Spanish30, thus it was available to use as a validating criterion in this study.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the reliability and validity of a Spanish version of the SAI-E.

Methods

Sample

The sample for this study comes from the "Centro de Reposo de Enfermedades Mentales de Piura y Talara" (CREMPT), placed in 'San Juan de Dios' Hospital (Piura, Peru). In this region, the mother tongue of the vast majority of the population is Spanish. However, given the high levels of social deprivation in this area, outpatient status does not necessarily mean clinical stability. Thus, both in- and outpatients were approached over the period from October 2013 to January 2014.

Those patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder according to the 'Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV'31 were invited to participate in the study. A history of brain injury and drugs abuse were exclusion criteria. Participants provided written informed consent.

The study obtained ethical approval from the local Ethics Committee and all participants signed informed consent.

Assessments and scales

Sociodemographic and clinical variables were recorded. In particular, age, gender and level of education were considered for the analyses. Also, general psychopathology was assessed with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)32, which also includes an item for the assessment of (lack of) insight and judgement, i.e. the higher the score, the poorer the insight. Also, both the SAI-E and SUMD were used for this validation study purposes.

The Schedule for Assessment of Insight - Expanded version (SAI-E) was used to evaluate insight. This is a semi-structured interview easily applicable to clinical practice that provides separate insight scores based on David's model9: 'awareness of mental illness', 'relabeling of psychotic symptoms as abnormal' and 'compliance'.

The Scale of Unawareness of Mental Disorder (SUMD) measures those insight dimensions proposed by Amador10,33. Specifically, three general items evaluate awareness of having a mental illness, awareness of treatment effects, and awareness of social consequences of mental illness. In addition, 17 items assess awareness and attribution of specific symptoms33. The Spanish version of the SUMD30 was taken as the "gold standard" for this validation study.

The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)34 was used to measure overall psychosocial functioning, which ranges from 0 (poor functioning) to 100 (no functioning impairment at all).

Procedures

All the above assessments were carried out by the same senior psychiatrist (JS). Also, a second rater (AR), who was blind to the SAI-E scores, administered the SAI-E to a subsample formed of 10 patients randomly selected and scored separately by JS, in order to test the inter-rater reliability. The evaluation was conducted separately, with a maximum difference of two days.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 (Chicago, Il, USA). First, the internal consistency of the Spanish SAI-E version was calculated using Cronbach's alpha coefficient. Second, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were estimated in order to measure the inter-rater reliability, while the external validity was measured with the SUMD and PANSS insight item through bivariate correlations. Also, further bivariate correlations between five psychopathological dimensions from a PANNS32 factorial analysis35 and the three insight dimensions assessed by the SAI-E were conducted.

Results

Sample characteristics

The sample was composed of 39 patients. The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1.

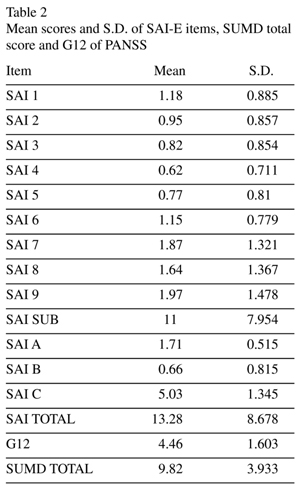

Of relevance, most of patients were severely psychotic. Thus, the mean score of PANSS total score was 80.46 (± 19.17), including very limited overall insight (PANSS lack of insight item: 4.46 ± 1.60). The mean total score for the SAI-E was 13.28 ± 8.68 and SUMD total score mean was 9.82 ± 3.93. These scales ratings are presented in Table 2.

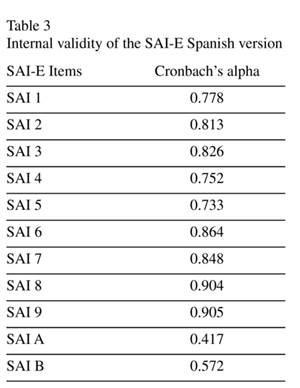

Internal validity SAI-E

For evaluating internal validity, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was estimated. In particular, for total insight this coefficient was 0.942. Coefficients for individual items are detailed in Table 3.

Inter-rater reliability

The inter-rater reliability was calculated using the ICC in a subsample of (n = 10) patients, which ranged from 0.992 to 1. The ICC for the total subscale was 0.99. ICC was used instead of the Kappa index due to the quantitative and continuous nature of the variables, with the risk of accepting that our sample is normally distributed.

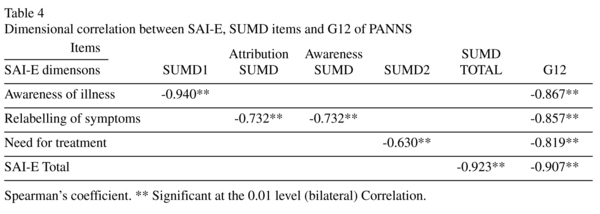

External validity

In terms of external validity, the insight item of the PANSS and the SUMD scores showed similar significant bivariate correlations with the three insight dimensions proposed by David, which are presented in Table 4.

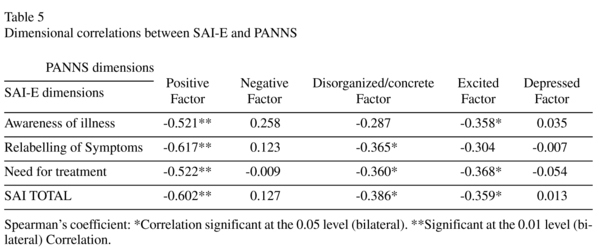

Insight dimensions correlations with psychopathological symptoms

Table 5 shows the correlations between the three dimensions of insight and five PANSS dimensions. Awareness of illness correlated with the Positive factor and Excited factor (r = -0.521, r = -0.358, respectively, p < 0.01). Relabeling of symptoms was found to correlate with both the Positive (r = -0.617, p < 0.01) and Disorganized factor; (r = -0.365, p < 0.05). Need for treatment showed significant correlations with Positive (r= -0.522, p < 0.01), Disorganized (r = -0.360, p < 0.05) and Excited factors; (r = -0.332, p < 0.05).

Discussion

Main findings

This study aimed to validate the Spanish version of the SAI-E when administered to a sample of Spanish-speaking patients with schizophrenia and related disorders. In particular, our results appear to validate the use of this Spanish version of the SAI-E to assess insight in patients with psychosis in Latin American in- and outpatient settings given its good internal and external validity and reliability.

Specifically, the mean total score of SAI-E from our study (13.28) was similar to previous samples of inpatients27,36, which are comparable with our mixed setting in terms of symptoms severity given the specific socioeconomic characteristics of North-Peru, particularly the limited access to inpatient care (the threshold for admissions is much higher than in the Western world). Thus, participants in previous outpatient studies were reported to have similar levels of total insight to our subsample of outpatients4,28 (mean SAI-E: 16.48).

With regard to the inter-rater reliability (n = 10), our ICC was 0.99 for the total insight score. Also, individual items ICCs ranged from 0.992 to 1, which is in line with recent validation studies in Greece4, Brazil27 and Tunisia28; being all above scores over 0.72, which had been found in the validation study of the original version of the SAI5.

Thus, the Spanish version of the SAI-E showed satisfactory internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.94 for the total scale scores. Of note, those items concerning adherence were found to be relatively low (0.417 and 0.572 respectively). However, these findings were in line Konstantakopoulus study et al.'s4, while the Nakhli validation study found a higher consistency across items28. These differences may be due to the characteristics of samples. Thus, these two studies4,28 used a sample of chronic patients and outpatients respectively, whereas the study by Nakhli and colleagues28 was limited to stable patients (PANNS total < 90 and a minimum duration of the illness of three years).

Alternatively, these mixed findings may be also be related to the existence of different adherence profiles. Thus, Roe et al.37 described four narrative profiles of insight (integrative insight, accepts illness / rejects labels, passive insight, and rejects illness) indicating the importance of distinguishing adherence from insight [38]. Thus, Konstantakopoulus et al4 described two groups of patients in relation to this aspect of insight, namely "insight induced" and "insight spontaneous", which are similar to the passive and integrative profiles reported by Roe et al, respectively. Adherence may also be affected by other external contributing factors such as past experiences of treatment, therapeutic relationships with the mental health professional, the level of community support and cultural background24.

Of relevance, convergent validity was found to be satisfactory for total scores and individual items when compared with the PANSS insight item, which is in full agreement with previous studies4,28,36. In addition, a good correlation between the total score of the SAI-E and SUMD was reached. Moreover, when individual insight dimensions were analyzed, these correlations remained significant for most SAI-E and SUMD items, consistently with a previous study39.

Associations of insight dimensions with psychopathology and functioning

Of note, with regard to psychopatholgy and insight, we replicated a negative relationship between the PANSS positive factor and the three insight dimensions. Thus, our results are in full agreement with a previous meta-analysis22, which encompasses 40 studies and revealed a small negative association between awareness of mental illness and positive and general symptoms. Also, both the disorganized and excited factors showed significant negative correlations with insight. However, our study failed to replicate associations of depressive and negative symptoms with insight dimensions, in line with a previous study40. These findings were, however, relatively in contrast to the aforementioned meta-analysis22, which may have been due to the overall psychotic severity of our patients. In keeping with our results, Cuesta et al. also found a correlation with disorganized, excited and negative schizophrenic dimensions while they failed to report further relationships with other Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale dimensions such as depression and positive symptoms41.

Insight had also been reported to predict long-term functioning in psychosis6. Thus, we found a cross-sectional association between total insight and psychosocial functioning, consistently with previous studies4,42. It could therefore be speculated that insight may improve long-term psychosocial functioning in patients with psychotic disorders via increased compliance with medication, which contributes to long-term symptomatic stability. In addition, engagement with mental health services, which has been associated with insight6, may help patients meet complex social needs such as employment and housing. Hence, insight may positive affect thus overall psychosocial functioning, particularly taking into account the high levels of social deprivation in our catchment area.

Influence of culture

Of relevance, in the study population region, which is close to the Andean highlands, certain 'cultural syndromes' have been previously described, particularly the so-called "Susto" (shock in Spanish), which is highly prevalent in Peruvian Andes43. This phenomenon consists of a magical or spiritual explanation for all kinds of ailments, which originally comes from Quechua culture, including a wide range of variations throughout Latin America. The soul (not according to the Christian meaning) is thought to leave the body due to strong reactions in places inhabited by mythical beings. Thus, symptoms can range from mild somatic symptoms such as headaches to hallucinations and delusions. More severe patients can go on to die by suicide in relation to nihilistic delusions or as coping strategies with medically unexplained symptoms44. Also, those affected by this 'syndrome' receive treatments and rituals delivered by shamans and healers. In our study, 65.5 % of participants reported having 'ever' been seen by local healers or shamans. This alternative approach to mental illness conceptualisation relates to previously reported non-medical models of illness45,46. Of note, our results appear to support the usefulness of the SAI- E to measure insight across cultures15,29. Thus, since the SAI-E consists of a 'semi-structured' interview enquiring about insight dimensions, the examiner can formulate the SAI-E questions in accordance with the patient cultural background.

Strengths and limitations

To our best knowledge, this is the first study aimed to validate the Spanish version of the SAI-E and can be generalized to other Spanish-speaking countries. Thus, while our findings may contribute to this area, namely insight in psychosis, replication studies are needed and our findings should be taken cautiously.

In addition, several study limitations should be borne in mind when interpreting our results. In particular, our sample may have been too small, which was also mixed with regard to patient status (both in- and outpatients were included) and illness stage, but the most important limitation is the small sample for inter-rater reliability. Also, the same researcher (JS), who had a good knowledge of the patient clinical status and cultural background, administered the SAI-E, the PANSS, and SUMD in the same interview, which may have biased these ratings and increased their correlation.

Conclusion

In summary, the SAI-E Spanish version has been demonstrated to have sufficient external validity and psychometric properties for it to be used for a multidimensional insight assessment in Spanish-speaking patients in Peru with schizophrenia and related disorders.

Conflict of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest concerning the subject of this study.

Additional contributions

All the authors have collaborated in this study and have approved the final manuscript.

References

1. Amador XF, Flaum M, Andreasen NC, Strauss DH, Yale SA, Clark SC, et al. Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and schizoaffective and mood disorders.Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994; 51(10): 826-36. [ Links ]

2. Drake RJ, Haley CJ, Akhtar S, Lewis SW. Causes and consequences of duration of untreated psychosis in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000; 177: 511-5. [ Links ]

3. López-Moríñigo JD, Wiffen B, O'Connor J, Dutta R, Di Forti M, Murray RM, et al. Insight and suicidality in first-episode psychosis: understanding the influence of suicidal history on insight dimensions at first presentation. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2014; 8(2): 113-21. [ Links ]

4. Konstantakopoulos G, Ploumpidis D, Oulis P, Soumani A, Nikitopoulou S, Pappa K, et al. Is insight in schizophrenia multidimensional? Internal structure and associations of the Greek version of the Schedule for the Assessment of Insight-Expanded. Psychiatry Res. 2013; 209(3): 346-52. [ Links ]

5. David A, Buchanan A, Reed A, Almeida O. The assessment of insight in psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1992; 161: 599-602. [ Links ]

6. Amador XF and David AS. Insight and psychosis: awareness of illness in schizophrenia and related disorders. 2nd ed. 2004, Oxford: Oxford University Press. xiv, 402 p. [ Links ]

7. Lin IF, Spiga R, Fortsch W. Insight and adherence to medication in chronic schizophrenics. J Clin Psychiatry. 1979; 40(10): 430-2. [ Links ]

8. Amador XF, David AS, Yale SA, Gorman JM. Awareness of illness in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull, 1991; 17(1): 113-32. [ Links ]

9. David AS. Insight and psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1990; 156: 798-808. [ Links ]

10. Amador XF, Strauss DH, Yale SA, Flaum MM, Endicott J, Gorman JM. Assessment of insight in psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1993; 150(6): 873-9. [ Links ]

11. McEvoy JP, Apperson LJ, Appelbaum PS, Ortlip P, Brecosky J, Hammill K, et al. Insight in schizophrenia. Its relationship to acute psychopathology. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989; 177(1): 43-7. [ Links ]

12. Lysaker PH, Roe D, Yanos PT. Toward understanding the insight paradox: internalized stigma moderates the association between insight and social functioning, hope, and self-esteem among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2007; 33(1): 192-9. [ Links ]

13. Cuesta MJ, Peralta V. Lack of insight in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull, 1994; 20(2): 359-66. [ Links ]

14. Aleman A, Agrawal N, Morgan KD, David AS. Insight in psychosis and neuropsychological function: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2006; 189: 204-12. [ Links ]

15. Saravanan B, Jacob KS, Prince M, Bhugra D, David AS. Culture and insight revisited. Br J Psychiatry. 2004 Feb; 184: 107-9. [ Links ]

16. Saravanan B, David A, Bhugra D, Prince M, Jacob KS. Insight in people with psychosis: the influence of culture. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2005; 17(2): 83-7. [ Links ]

17. Wiffen BD, O'Connor JA, Russo M, Lopez-Morinigo JD, Ferraro L, Sideli L, et al. Are there specific neuropsychological deficits underlying poor insight in first episode psychosis? Schizophr Res. 2012; 135(1-3): 46-50. [ Links ]

18. Poole NA, Crabb J, Osei A, Hughes P, Young D. Insight, psychosis, and depression in Africa: a cross-sectional survey from an inpatient unit in Ghana. Transcult Psychiatry. 2013; 50(3): 433-41. [ Links ]

19. Crumlish N, Whitty P, Kamali M, Clarke M, Browne S, McTigue O, et al. Early insight predicts depression and attempted suicide after 4 years in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005; 112(6): 449-55. [ Links ]

20. López-Moríñigo JD, Ramos-Ríos R, David AS, Dutta R. Insight in schizophrenia and risk of suicide: a systematic update. Compr Psychiatry. 2012; 53(4): 313-22. [ Links ]

21. Mutsatsa SH, Joyce EM, Hutton SB, Barnes TR. Relationship between insight,cognitive function, social function and symptomatology in schizophrenia: the West London first episode study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006; 256(6): 356-63. [ Links ]

22. Mintz AR, Dobson KS, Romney DM. Insight in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2003; 61(1): 75-88. [ Links ]

23. Belvederi Murri M, Respino M, Innamorati M, Cervetti A, Calcagno P, Pompili M, et al. Amore M. Is good insight associated with depression among patients with schizophrenia? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2015; 162(1-3): 234-47. [ Links ]

24. Kemp R and David A. Insight and compliance. Blackwell, B. (Ed.), Treatment Compliance and the Therapeutic Alliance, 1997: p. 61-84. [ Links ]

25. Birchwood M, Smith J, Drury V, Healy J, Macmillan F, Slade M. A self-report Insight Scale for psychosis: reliability, validity and sensitivity to change. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994; 89(1): 62-7. [ Links ]

26. Marková IS, Berrios GE. Insight in clinical psychiatry. A new model. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995; 183(12): 743-51. [ Links ]

27. Dantas Cde R, Banzato CE. Inter-rater reliability and factor analysis of the Brazilian version of the Schedule for the Assessment of Insight: Expanded Version(SAI-E). Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2007; 29(4): 359-62. [ Links ]

28. Nakhli J, Mlika S, Bouhlel S, Amamou B, Chaieb I, Ben Nasr, et al. Translation into Arabic and validation of the Schedule for the Assessment of Insight-Expanded Version (SAI-E) for use in Tunisia. Compr Psychiatry. 2014; 55(4): 1050-4. [ Links ]

29. Saravanan B, Jacob KS, Johnson S, Prince M, Bhugra D, David AS. Assessing insight in schizophrenia: East meets West. Br J Psychiatry. 2007; 190: 243-7. [ Links ]

30. Ruiz A, Pousa E, Duñó R, Crosas J, Cuppa S, García C. (Spanish adaptation of the Scale to Asses Unawareness of Mental Disorder (SUMD)). Actas Esp Psiquiatr.2008; 36(2): 111-1198. [ Links ]

31. First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. New York State, Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, New York, 1997. [ Links ]

32. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS)for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987; 13(2): 261-76. [ Links ]

33. Amador XF. The scale to assess unawareness of mental disorder. Columbia University and New York State, Psychiatric Institute, 1990. [ Links ]

34. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC, USA: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [ Links ]

35. Wallwork RS, Fortgang R, Hashimoto R, Weinberger DR, Dickinson D. Searching for a consensus five-factor model of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012; 137(1-3): 246-50. [ Links ]

36. Sanz M, Constable G, Lopez-Ibor I, Kemp R, David AS. A comparative study of insight scales and their relationship to psychopathological and clinical variables. Psychol Med. 1998; 28(2): 437-46. [ Links ]

37. Roe D, Hasson-Ohayon I, Kravetz S, Yanos PT, Lysaker PH. Call it a monster for lack of anything else: narrative insight in psychosis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008; 196(12): 859-65. [ Links ]

38. Morgan KD, Dazzan P, Morgan C, Lappin J, Hutchinson G, Suckling J, et al. Insight, grey matter and cognitive function in first-onset psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010; 197(2): 141-8. [ Links ]

39. Gilleen J, Greenwood K and David AS. Anosognosia in schizophrenia and other neuropsychiatric disorders: similarities and differences. In: G.P. Prigatano, (Ed.) The Study of Anosognosia, Oxford University Press, 2009; 255-290. [ Links ]

40. Danki D, Dilbaz N, Okay IT, Telci S. (Insight in schizophrenia: relationship to family history, and positive and negative symptoms). Turk Psikiyatri Derg.2007; 18(2): 129-36. [ Links ]

41. Cuesta MJ, Peralta V, Zarzuela A. Psychopathological dimensions and lack of insight in schizophrenia. Psychol Rep. 1998; 83(3 Pt 1): 895-8. [ Links ]

42. Lincoln TM, Lüllmann E, Rief W. Correlates and long-term consequences of poor insight in patients with schizophrenia. A systematic review. Schizophr Bull. 2007; 33(6): 1324-42. [ Links ]

43. Bernal-Garcia E. Folk Syndrome in four cities in the peruvian hihglands. Anales de Salud Mental. 2010; 26(1): 39-48. [ Links ]

44. Rubel AJ, Nell CO, Collado-Ardon R. Susto: A Folk-Illness. University of California Press, Berkeley, 1984. [ Links ]

45. Kapur RL. Mental health care in rural India: a study of existing patterns and their implications for future policy. Br J Psychiatry. 1975; 127: 286-93. [ Links ]

46. Gater R, de Almeida e Sousa B, Barrientos G, Caraveo J, Chandrashekar CR, Dhadphale M, Goldberg D, al Kathiri AH, Mubbashar M, Silhan K, et al. The pathways to psychiatric care: a cross-cultural study. Psychol Med. 1991; 21(3): 761-74. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr. Juan Soriano-Barceló, MD

Psychiatry Department

University Complex Hospital of Santiago de Compostela

Travesia da Choupana, s/n. 15706

A Coruña. Spain

Tel. 0034981951063 - 0034981951481

E-mail: Juan.Soriano.Barcelo@sergas.es

Received: 19 July 2015

Revised: 9 December 2015

Accepted: 15 January 2016