Introduction

Women and girls make up around 7% of the world's prison population1,2, and the number of female inmates has increased more in recent decades when compared to male prisoners. The percentage of female prisoners in America was 8.4% in 2017, which is the largest female prison population in the world. The huge number of female inmates in Latin American countries is a cause for deep concern1,3. Women represent 5.3% of the prison population in Peru4.

Given that female inmates form a minority group, discrimination within the system is common. Their own special needs and characteristics are not taken into account, and there are unfavourable differences in terms of structure, treatment and health care5. Women entering prison generally belong to socially, educationally and economically disadvantaged groups, and suffer from a range of physical and mental pathologies6-8. The vulnerability of this group can be seen from the moment they are arrested, as they can be intimidated and coerced to sign declarations with serious legal consequences, or suffer sexual abuse and other forms of violence9. Furthermore, many female inmates are the only or main person responsible for their families, and sudden separation from their loved ones can bring about an intensely negative reaction5.

In comparison to male prisoners, the physical and mental health of female inmates is more likely to deteriorate as a result of overcrowding, lack of hygiene, inadequate nutrition10, the last of these being one of the major risk factors for chronic non-communicable diseases11, which are further aggravated by inappropriate and inadequate medical care12. The prison healthcare services in many countries are poorly equipped, understaffed and lack resources9, leading to imbalances in access to healthcare and violating fundamental rights6,12,13.

The Peruvian prison system does not meet international standards or constitutional guarantees on the protection of inmates' rights6. One of the main causes in structural terms is the critical level of overcrowding, which has an even greater effect on vulnerable groups7. In June 2020, the penal institutions of the National Prison Institute of Peru (INPE) reached levels of overcrowding of 126%4. The number of medical practitioners and other health professionals in prisons is way below what is really needed, further aggravated by other factors such as precarious working conditions, a severe shortage of essential medicines, medical materials and a shortage of ambulances, with the few that are available being obsolete and in poor condition14.

The rupture of social connections, and poor or non-existent family support, also have extremely negative affective consequences for female inmates, especially if they are mothers, and have a negative impact on their subsequent rehabilitation15. Incarceration of the mother can also have a devastating short and long term effect on the offspring. Many countries have different policies regarding the separation, custody and care of the young children of interned mothers or offer ways for the offspring to live with them in prison16. However, in the Latin American context, there are no solid mechanisms to protect and rehabilitate female inmates and minors after such a traumatic experience9.

The Peruvian Criminal Code states that female inmates are entitled to live with their children in prison until the child is 3 years old17.

The inadequate housing, dietary and living conditions in prison not only have a negative effect on the inmate but also have a drastic impact on the children who live with their mothers in prison. Their physical and mental development takes place in an unsuitable setting, where many opportunities necessary for someone of their age are missed16, and access to the medical care necessary for young children is lacking. The reduced and overcrowded spaces where they live and sleep, vulnerable conditions, the social problems caused by coexistence amongst inmates, shortages of medical resources and care, and the absence of recreational and educational spaces for children are issues that are glaringly evident in the Peruvian context6,14.

However, there are few recent studies in Peru that consider the complex question of the development of the mother-child relationship in prison. In view of this situation, this qualitative study has been proposed with the aim of exploring the experiences of female inmates living with their children in the Women's Prison of Chorrillos, in Lima, Peru, in 2020, with a view to contextualising and focusing subsequent proposals for improvement.

Materials and methods

The methods were described in accordance with the CoreQ recommendations18.

Study design

The qualitative, exploratory study was designed according to a phenomenological interpretative structure understood as a description and interpretation of human experiences and life situations19, through semi-structured interviews with female inmates who have children at the Women's Prison of Chorrillos.

Context

According to the latest report of the INPE (June 2020), 4,855 women are interned at 43 of the country's 67 prisons, and the Women's Prison of Chorrillos holds the largest number (n = 794), with 76% overcrowding. There were minors (n = 102) in 22 prisons, most of whom (n = 32; 20 boys and 12 girls) lived in the Women's Prison of Chorrillos4.

The female inmates with children at the Women's Prison of Chorrillos lived in a module apart from the rest of the population. The cells are for two persons, have one bathroom and the showers are shared. The diet for mothers is the same as for the rest of the population (three times a day), with an additional ration for the children. There is a prison infirmary that provides medical care for the entire population regardless of their incarceration regime. All the inmates can participate in occupational workshops and activities organised by the social and psychology services, which are subject to availability. During the working day, the children stay in their cradles and are attended to by the prison staff.

Research group

The interviews were carried out by the principal investigator, an obstetrician with training and experience in prison health management and research.

Population and study sample

The sample was intentional, diverse (maximum variation)19. The inclusion criteria were as follows: inmates of the Women's Prison of Chorrillos living with their child in the prison, willingness to participate in the study, physical and mental conditions that ensure that participation is freely consented to and that the answers are coherent.

A request was sent to the prison management to carry out the research. A total of 13 inmates with children participated in the study. Their sociodemographic, clinical and legal characteristics, arising from the problems and theoretical basis5,12,16, can be seen in Table 1. The inmates were invited to the interview by the prison staff at the principal investigator's request. Every participant was previously informed about the objectives and procedures of the study, after which the informed consent was read and signed. All the inmates were willing to participate.

Table 1. Socio-demographic, clinical and legal characteristics of incarcerated mothers at the Women's Prison of Chorrillos, Lima, Peru, in 2020

| Case no. | Inmate's age (years) | Place of origin | Educational level | Marital status | Offence committed | Prison sentence (years) | Diagnosis | Minor's gender | Minor's age (months) | Minor's state of health | Medical or surgical background of minor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 33 | Lima | Secondary education not completed | Cohabitant | Illegal drug trafficking | 6 | Clinically stable | M | 16 | Healthy | No |

| 2 | 26 | Arequipa | Secondary education completed | Single | Illegal drug trafficking | 5 | Clinically stable | M | 19 | Healthy | Unspecified anaemia |

| 3 | 25 | Piura | Secondary education completed | Single | Aggravated | 2 | Clinically | M | 14 | Healthy | No |

| 4 | 32 | Lima | Secondary education not completed | Cohabitant | Illegal drug trafficking | 6 | Clinically stable | F | 13 | Healthy | Premature birth |

| 5 | 30 | Lima | Secondary education not completed | Cohabitant | Aggravated burglary | 4 | Clinically stable | M | 27 | Healthy | Tachycardia |

| 6 | 19 | Lima | Secondary education completed | Single | Aggravated burglary | Awaiting trial | Clinically stable | F | 4 | Healthy | No |

| 7 | 21 | Colombia | Secondary education completed | Cohabitant | Illegal drug trafficking | Awaiting trial | Bronchial | M | 2 | Healthy | No |

| 8 | 28 | Lima | Higher | Cohabitant | Illegal drug trafficking | Awaiting trial | Clinically stable | M | 5 | Healthy | No |

| 9 | 25 | Lima | Secondary education not completed | Cohabitant | Aggravated theft | 4 | Clinically stable | M | 2 | Healthy | No |

| 10 | 24 | Junín | Secondary education completed | Single | Illegal drug trafficking | Awaiting | Clinically stable | F | 5 | Healthy | Unspecified allergy |

| 11 | 40 | Lima | Secondary education completed | Cohabitant | Murder | 30 | Clinically stable | M | 2 | Healthy | No |

| 12 | 22 | Lima | Secondary education not completed | Cohabitant | Grievous bodily harm | 6 | Epilepsy | F | 3 | Healthy | No |

| 13 | 23 | Lima | Secondary education not completed | Single | Aggravated burglary | 4 | Clinically stable | F | 19 | Healthy | No |

Note. F: female; M: male.

Categories and subcategories

The “experiences” category was represented by the following initial subcategories based on the background5,8,10,12,16 and a prior assessment of the context of the study (observation of the facilities and review of the prison regime): “family situation”, “experiences before imprisonment”, “experiences in prison”, “experiences in prison with regard to the child”, “personal care”, “ability to adapt to and accept prison discipline”, “interpersonal relations” and “legal situation”.

Data gathering instruments and process

With the objectives and methodology of the study in mind, the decision was made to gather the data through the script of semi-structured interviews designed by the research team and validated by a panel of eight experts. Each question had a Likert scale evaluation of 1-3. To establish the validity of the content, the total content validity coefficient was applied, giving a value of 0.9999999, which meant that the validity and concordance of the instrument were regarded as excellent.

The instrument consisted of 81 pre-designed questions that corresponded to eight initial subcategories. The interviews were carried out by the principal investigator at the prison infirmary with no third parties or children present, in a relaxed atmosphere (doctor's office with the door closed). Each interview lasted about 2 hours. The narrative data was gathered from the handwritten material taken at the time of the interview, and later transcribed onto an MS Word document for digital storage. Self recording was not used due to the prohibition against entering the prison with electronic devices. Feedback and confirmation of the narrative data with the participants was carried out at the end of the interview. The information was systematically collected and organised using a phenomenological focus in September 202019 until the categories were theoretically saturated when the information obtained systematically repeated. Likewise, to ensure the quality of the research, the following standards were applied: credibility, accountability and transferability20.

Data analysis

After the principal investigator had compiled the information, recorded it by hand and transferred it to a digital format, it was then reviewed in detail by both investigators to ensure quality and consistency. The interviews were codified for confidentiality. Data collection matrices with the most relevant subjects were prepared. The emergent typologies were reviewed and grouped, and the content was then analysed and interpreted. The circular process used in the qualitative method was applied (commonly understood as collection, review, codification, analysis and interpretation of the data throughout the process). Criteria of inclusion, analysis and reflection were followed. The results obtained were the outcomes of a consensus reached by the investigators (investigator triangulation).

Ethical considerations

The research project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Norbert Wiener Private University of Lima, Peru (Doc.117-2020) and complied with the Helsinki Declaration. The study procedures were explained to the participating inmates, and they signed the informed consent to express their voluntary acceptance of the process. Every effort was made to ensure that the data used in the research proceedings was for purely scientific purposes and confidentiality was maintained at all times.

Results

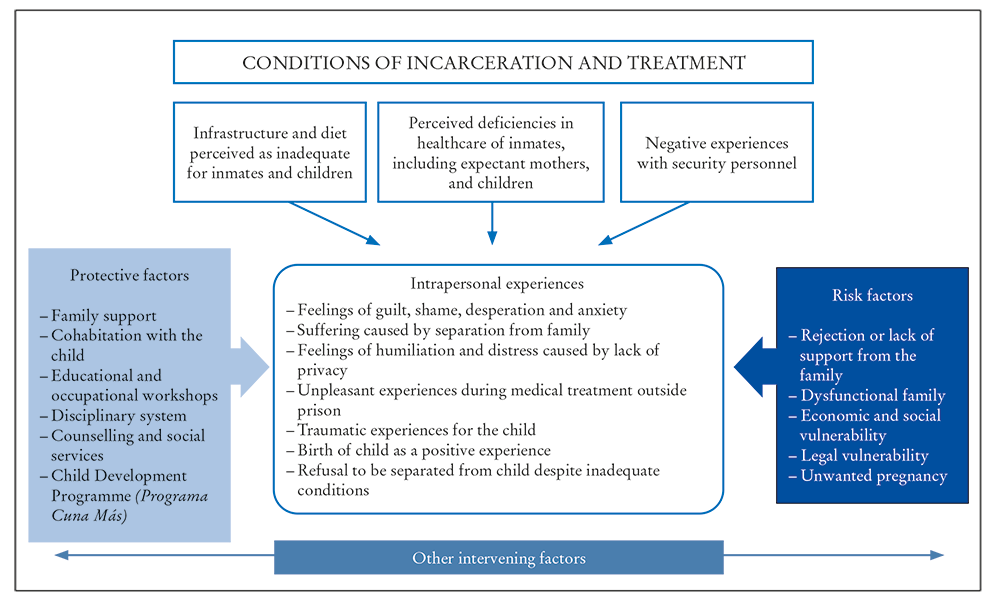

The findings of the study were grouped into three thematic areas (Figure 1) that are described below along with the textual quotations.

Intrapersonal Experiences

The predominant feelings of many participants when describing their experiences in prison were guilt, regret, desperation and anxiety:

“…I feel really desperate, we live with a lot of anxiety here…, day to day life here is really horrible” (case 1).

“…help us, there are a lot of mothers who are really suffering here too...” (case 3).

“…I was already 6 months pregnant when I entered prison…there were a lot of feelings, mostly guilt, pain, I felt very ashamed about what I did…” (case 10).

One of the main causes of suffering for inmates was separation from the family:

“…I feel really bad because I call my children and they ask me why they can't see me, why I don't take them to school, why I'm not helping them with their homework [crying]” (case 4).

The mothers were also aware that they were going to be separated from their child when he/she was 3 years old, which caused intense distress:

“…it's going to be really difficult…I've seen cellmates whose children have gone, I can imagine what's going to happen…” (case 10).

Other inmates mentioned feelings of humiliation and distress because of the lack of privacy:

“…I don't like people looking at me, and here you have to get undressed and change your clothes in front of all the girls, you have no privacy…” (case 5).

Some inmates were victims of psychological abuse from other inmates:

“…other inmates that make fun of my health, they laugh, they imitate my fits” (case 12).

All the interviewees gave birth in a public hospital, where the common denominator was feelings of discrimination because of their legal situation:

“…it was horrible because there were a lot of interns and quite a few women were about to give birth, but more interns came to my bed probably because I was from prison, I felt uncomfortable, like discriminated against” (case 2).

“… care during the delivery was horrible, I felt like people were glaring at me or like…discriminated, embarrassed too…” (case 9).

Many mothers also mentioned the physical and psychological distress caused by being handcuffed before, during and after labour:

“I felt bad emotionally, bad, bad, bad, it really hit me there…they treated me really badly, they put cuffs on my hands and feet and I had no way of holding my daughter, they imposed a lot of restrictions, I asked to go to the bathroom and the guard said: “do it in your diaper”, I complained about things, but they paid no attention, and that's where I felt really powerless, I got even more depressed there” (case 6).

“… I felt bad, I couldn't rest, I couldn't sit down because I was handcuffed too, chained to the bed when I gave birth…really horrible…” (case 12).

Several inmates described the suffering they felt for their children's traumatic experiences during transfer and confinement in another prison:

“…a really bad experience, a psychological trauma for the babies, my boy cried, miss, cried and cried, because he was scared of the vehicle” (case 1).

“I don't know why they transferred us…honestly, we've been cold, we've been hungry, we've gone through things that a child shouldn't have to live through, honestly…children crying of hunger…” (case 5).

In the other hand, the inmates commented on the birth of their child as a moment of happiness despite being in prison:

“…the happiest moment here in prison was when my baby was born” (case 9).

“…the day my daughter was born…when I saw her, it was unforgettable, the happiest day...” (case 10).

One frequent finding was the mother's refusal to be separated from the minor despite the inadequate conditions in prison:

“…it was the most painful day of my life when I had to leave my children, I wouldn't like to leave my son and watch him go when he's 3, that's just too painful, I couldn't cope with that” (case 1).

“…I don't want to be separated, at least she makes me feel better, it'd be worse here without my daughter” (case 4).

“…I don't want my son to leave my side, I want him here, I want to look after him, I feel good with him, full of life, he's everything, he's my strength, all my happiness”(case 9).

Conditions and treatment in prison

All the interviewees commented on major structural, organisational and interpersonal defects regarding prison conditions and treatment.

One of the most common observations was overcrowding:

“…I've been sleeping on the floor for two years… there's marihuana, noise, fighting, overcrowding” (case 11)

“…here there aren't many workshops and there are too many people, they can't cope with it all…” (case 5)

The infrastructure was regarded as inappropriate and unhealthy for inmates:

“…we sleep on a cement bed, we don't have a waste bin, we've got nowhere to wash clothes, there's a lot of damp” (case 11)

The food was also regarded as inadequate for the inmates, including breastfeeding mothers:

“…the food is disgusting, a lumpy mess, sometimes with cockroaches, sometimes they don't cook the rice or the vegetables correctly, they're all half cooked, it's all disgusting, disgusting, disgusting” (case 1).

“…the food is terrible, we had soup a few days ago and there were cockroaches in it and we asked them for rice with an egg because we were breastfeeding… it's true, it makes you hungry…a lot of people get ill with tuberculosis because of the food, there's a lot of tuberculosis here…” (case 8).

The prison conditions and diet for the children were also mentioned as being unsuitable and hazardous for the physical and mental development of the minor:

“… the infrastructure is inadequate, there isn't enough freedom for the child to develop…there are inmates who swear, there are inmates who behave badly and the kid is seeing all this…” (case 2)

“…then my daughter ended up with lung disease because I live in damp conditions, it's all made of cement, the place where I am is very cold for her” (case 4)

“…the people who live here have really bad habits, they smoke and the children have to inhale the smoke…you can see women with other women, couples, they're hugging and kissing each other” (case 5)

“…the babies break, break the door, they kick and scream, my boy has colic, I can't get out…the food for the children?… all the babies here have low haemoglobin and their teeth are bad…” (case 11)

“…they always give them the same, the food is nasty, they're not well fed…all the children have anaemia” (case 4)

Another important factor for the inmates with children was the major shortages in healthcare for inmates, including expectant mothers, and children.

An important finding of the study was the perceived indifference and mistreatment by prison health staff:

“when they're in a bad mood, they shout at you,… when I feel bad, when it hurts, they say “What do you expect?, that's life. isn't it”,…my pregnancy was difficult, but they didn't help, no matter how much I screamed from the pain” (case 11)

“the staff attention is dreadful, because they pay no attention to the ones who are pregnant, if you're bleeding like a pig, they pay no attention…” (case 1)

“…even now the cut from the C-section is open and it won't close, I've begged them to take me to the hospital, and no reply …my daughter was born prematurely, she's even had convulsions and no one in the medical unit wanted to take her to the hospital, they just said that if anything happened to here it was my responsibility” (case 4)

“…when I was about to give birth, they treated me very badly here, I begged them, I begged and begged, they didn't take me to hospital, they didn't take me, they injected me with something because they wanted to keep me here, I had a really bad time…” (case 6)

“…if they really treated me badly, it wasn't so much because of me but because of the baby …no doctor treats you well here, not one of them” (case 7).

They also mentioned the lack of essential medicines:

“…the treatment is appalling, you have to have a fever because if you don't, they don't treat you and the only thing they give you for every illness is paracetamol, nothing else…” (case 7).

“the most neglected ones are the children ..the magic pill is paracetamol, the panacea…” (case 11)

“…my son's temperature went up to 40, they gave him an injection and told me that they wouldn't be held responsible because there were no other medicines” (case 8).

The prison also lacks paediatric care:

“… the doctor said: ‘'I'm not going to treat you because I don't know about that, I'm not a paediatrician'' (case 7).

“…they say me: “I'm not a paediatrician… I'm going to give you this, and it's your responsibility” (case 13).

Some inmates regarded the mental health care as defective:

“…a cellmate was very depressed and cried, she killed herself, she committed suicide, they paid no attention to her…” (case 3).

Finally, several inmates had negative experiences related to the security personnel, including abuse, and racial and social discrimination:

“The discipline, they're abusive, there's a lot of abuse of authority…if they see an inmate who's poor or from the provinces, they treat her like a doormat…” (case 1).

“…security treats us as if we were nothing…” (case 7).

“…some guards want to treat you badly… they want you to feel like you're the worst thing in the world” (case 8).

Other intervening factors

Not all the inmates who participated in the study had such severe experiences despite the similarity in conditions. The other factors that could considerably modify adaptation to life in prison and its conditions and later reinsertion were identified.

Notable risk factors included abandonment or lack of support from the family, dysfunctional families, economic, social and legal vulnerability, and unwanted pregnancy:

“…my family don't come either, … my partner left me, turned his back on me…” (case 1).

“…my mother was imprisoned twice for theft, the first time when she was pregnant with me, and the second time when I was nine, she was back in here again…” (case 13).

“…I felt a lack of care, a lack of family, I was always alone, and that made me get into bad company, and the economic problems with having a sick daughter led to me crime…” (case 11).

“…my sister died from feminicide…and my two orphan nephews were what made me decide to be a drug mule…” (case 10).

“…I looked at my children and felt really scared, then he threatened me and said that if I didn't make the trip, people know my address, my personal details, they'd go to my house…” (case 4).

“my husband had to work with the baby on the motorbike and the bike crashed twice with the baby on board …I had to bring the kid here” (case 5).

“The police didn't let me call my family because I didn't want to sign their document that said that I had a gun, they got angry, they locked me in the holding cell, my family knew nothing…” (case 6).

“…I entered (prison) pregnant…I didn't want the baby…because it's a horrible place…” (case 7).

The following protective factors were also identified: family support; cohabitation with the minor; educational and occupational workshops; disciplinary regime; psychological and social care; the national infant development programme (Programa Nacional Cuna Más):

“my brothers and sisters, my mother, they supported me by paying for everything that has to be paid for here, my mother gave me advice, my sisters talked to me, I had emotional support…” (case 6).

“my husband helps me financially, he visits me, thank God that despite everything he didn't leave me” (case 8).

“…my daughter gives me a lot of light in the darkness, I want to get over all this for her sake” (case 10).

“…I learned to work because I didn't know how to work, and now I'm a micro-entrepreneur” (case 11).

“…I did the cosmetics workshop for one year, the teacher is really good, I learned a lot” (case 13).

“I've had a lot of help in getting a project in life, in getting myself organised, having a study diploma and going on to study outside…the social worker has helped me a lot” (case 1).

“the discipline has helped me to be a better person, because here I've got a timetable to do my stuff and outside I was disorganised…the psychologist and the social services really helped me…” (case 7).

“the infrastructure of the programme is really nice, it's for different ages” (case 10).

Discussion

The results of this study show that the experiences of incarcerated mothers at the Women's Prison of Chorrillos is a complex, multidimensional and multi-factorial phenomenon. The psychological distress and suffering experienced in the sample are commonly found in the female prison population, according to other studies5,8. It has also been shown that the negative impact of imprisonment, especially separation from the family, is more severe amongst women than men, and has a greater effect on the children21. For women who are pregnant or living with their children in prison, there are other added concerns such as health, diet, and the infant's development and wellbeing. Similar findings were reported in prisons in Indonesia22. However, no relation has been established in Spain between the levels of wellbeing and maternity amongst inmates8, possibly because of the different conditions of internment there.

A major negative experience for the sample population was related to pregnancy during incarceration and care during delivery at the public hospital. The physical and psychological suffering was caused by poor perinatal care, inappropriate referral, security conditions and perceived discrimination. Similar results were reported amongst pregnant internees in England and Brazil23,24. In their study, Kelsey et al., found breaches of the standards of care established by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists25.

At the same time, this study also found that the child's birth and cohabitation with the infant in prison is an experience that provides happiness and is a protective factor that enables the inmates to cope with conditions in prison, which is also mentioned in the study by Soares et al. in Brazil26. The mothers refused to be separated from their children, despite the inadequate conditions for the minor. Likewise, the fact that the child would have to leave the mother at a given age was a cause of additional suffering for mothers, who were unable to cope with the likelihood of this happening. This problem was also mentioned in the studies carried out in Brazil27 and the UK28.

The shortage of public resources for female inmates, including inadequate infrastructures and limited access to good quality health services, as shown in this study, not only have a negative effect on the inmates but also, and more so, on the infants who live with them, which matches the evidence from studies in Europe, Africa and America12,13,16,21,23-25,29. One other notable outcome of the study was the dehumanising attitude of the medical staff, which cannot be justified as a result of structural deficiencies. As Vildoso-Cabrera et al. state in their research, current prison policies in Peru are limited solely to the expectation of larger budgets for infrastructure or medicines, and neglect the ethical and human aspects of care for inmates and children13.

The dietary deficiencies in the study have a very significant impact on the inadequate health of the inmates and on the infants' development, as shown in Brazil11 and Kenya30. Unlike other articles, this study not only found shortages in the quantity and variety of food, but also in the storage and preparation, which also reflects issues with attitudes that require more attention.

Finally, the efforts made at different levels of the penitentiary system to address the situation should be acknowledged. The national child development programme, called Programa Nacional Cuna Más, is a multi-sector initiative that includes educational and occupational workshops, psychological care and social services, and was seen as a very positive and important measure by some of the interviewees. However, overcrowding acts as an impediment to inmates' fair and sustainable access to the services. A study carried out at another women's prison in Lima showed that work and educational activities contributed towards the inmates' good mental health5.

This study is the first one in Peru to consider the problems described from a qualitative perspective. The limitations of the study include the ones inherent to the phenomenological design when the interpretation of the experiences of the persons studied by the investigators can involve their own values when gathering and analysing the information; and a possible social desirability in the answers. To reduce such biases, a large number of open questions were used, while two investigators participated in the analysis: an obstetrician and a psychiatrist, both of whom were also specialists in health management. There were there no difficulties in gaining access to the prison or the sample.

Another limitation is that of carrying out a study at a prison in the capital city, given that the economic, social and cultural realities of the provinces of Peru are much more unfavourable than in Lima. Other research projects at prisons around the country may be effective in helping to adapt the corrective measures, considering the cultural and socioeconomic differences of each region. It would also be important to involve the medical, administrative and security personnel in such studies.

By way of conclusion, the results show evidence of severe structural and organisational deficiencies that infringe the fundamental rights of the group that was studied. It is important to not only address the material limitations, but also to strengthen the organisational culture and processes involved in health care, treatment in prison and social rehabilitation with an emphasis on sustainable preventive and promotional programmes. There is a need to create more scientific evidence to reduce the harmful effects of imprisonment during infancy.