Introduction

The World Health Organisation has for some time defined health as "a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity". This definition was criticised as utopian at the time and echoes of such opinions can still be heard. However, there is now sufficient evidence to suggest that health can be created through strategies that are combined and maintained for long enough to bring about measurable results. This concept is now called health promotion.

The Ottawa Charter defined five main action areas for health promotion: building a healthy public policy, creating supportive environments, strengthening community action, developing personal skills and re-orienting healthcare services.

A "setting or environment for health" is defined as the place or social context in which persons carry out daily activities and where environmental, organisational and person factors that affect health and wellbeing interact. Recent decades have seen successful attempts to develop healthy environments in a range of settings, such as education centres, the workplace, cities, hospitals and markets1-3.

Prisons can be settings for health, given that there is a very real possibility of promoting it there. However, prisons are closed and highly regulated environments and so situations may arise where persons lose control over conditions that can affect their health. They should therefore be protected from such risks and special attention needs to be paid to the physical, mental and social characteristics of this setting; not so much to promote health but rather to ensure that the health of the inmates and staff who work there does not get any worse. Imprisonment should be the only sentence imposed on inmates. Prisons should ensure that all the rights guaranteed by the Spanish Constitution for all citizens are complied with4-6.

Working with the notion that the mission of the persons employed in the prison system is to offer male and female inmates the opportunity to make positive changes and positively transform their lives, the healthy prisons movement commenced in England when a White Paper published in 1992 listed the elements necessary for the "health of the nation" and identified the following working areas: schools, homes, the workplace, hospitals and prisons. The development of healthy prisons in Liverpool led to this concept being transmitted to other European countries.

A healthy prison needs to be committed to health promotion for the prison population. The healthy prison is based on the diagnosis of needs identified by both inmates and medical personnel, and promotes wellbeing that has its roots in a participative process in the prison community5,6.

Health is now regarded as a resource for life and the vast majority of the prison population has not had the opportunities needed to acquire and maintain a "health capital". We should put health at the service of rehabilitation and reintegration, and protect vulnerable individuals in the prison setting from entering a vicious circle of exclusion.

Health promotion of the prison population represents an enormous challenge. The idea of health for many marginal groups is very different from that of the general public, for whom most programmes and activities are designed. For inmates, health means the absence of disease and has a relative value. This is hardly surprising, given that their lives outside prison are focused on survival and this attitude defines their priorities. Prison often appears as a restricted space with tough social relationships, but is also one where someone "doesn't have to fend for himself every day". For this reason, at a moment of rupture caused by imprisonment and relative calm, inmates might willingly accept health promotion, especially if it is attractive and linked to tangible and attainable improvements. The activities should be methodologically well designed and systematically evaluated4,7,8.

Prisons are a difficult challenge, but at the same time they represent an opportunity to deal with the complex needs of a vulnerable population, with specially adapted and fair medical treatment. We should not therefore be surprised if the next stage in the process is to turn our prisons into healthy environments.

The general aim of this study is to analyse the implementation of health promotion in Catalonian prisons, Several objective were proposed with this objective in mind:

Describe the socio-demographic characteristics of the nursing staff working in Catalonian prisons.

Identify what types of health promotion programmes have been carried out in Catalonian prisons over the last five years.

Identify the elements that may interfere with the implementation of health promotion programmes in this setting.

Establish the relationship between the operating time of the prison and the number of health promotion projects.

Material and method

Design

Descriptive, observational, retrospective and transversal multi-centre study carried out between January 2019 and October 2020.

Scope of study

Category 1 and 2 prisons in Catalonia. Category 3 prisons and the Prison Hospital Unit of Terrassa were excluded. The Catalonian prisons that were included were: Barcelona Women's Prison, Ponent: Quatre Camins, Brians 1, Brians 2, Young Persons' Detention Centre, Lledoners, Puig de les Basses and Mas d'Enric.

Population

The study included all the nursing professionals of the above mentioned prisons, which makes a total population of 99 professionals.

Data instruments and gathering

The data gathering instrument consisted of an ad hoc questionnaire.

There was no questionnaire validated for use in the study, which meant that a detailed review of the bibliography was necessary. The purpose was to identify and include the elements that enabled the health promotion programmes carried out in prisons to be evaluated in order to effectively meet the objectives defined in this investigation.

The questionnaire underwent a pilot test with a group of professionals made up of ten nurses, to evaluate readability and understanding of the questions, The areas included were drafting, expression, understanding and possible causes of error or confusion. The suggested changes were included to validate the questionnaire in terms of understanding and readability.

The questionnaire consisted of 31 questions, 5 of which were open-ended while 26 were closed, and had the following structure:

A first block of six questions, with two possible answers, which provided information about the variables: sex, higher education studies in health promotion, worked in the prison when it was managed by the Department of Justice, health promotion programmes carried out between 2015 and 2018, health promotion programmes carried out in 2019 and health problems that required management based on health promotion.

A second block of 14 questions, with more than two possible answers. The questions provided information about the variables: prison, type of nursing study, instigators of health promotion programmes, appraisal of prison setting for implementing health promotion programmes, barriers/difficulties of the prison setting with regard to health promotion, facilities/strong points of the prison setting for health promotion and type of health problem that should be treated with health promotion.

A third block of four questions, with more than two possible answers in sequence. These questions provided personal information about the levels of satisfaction and level of usefulness by the person taking the survey.

A fourth block with two questions, which were evaluated on a continuous scale. These gave information about the number of health promotions programmes that were carried out and were grouped into five intervals (from one single programme to five or more).

As the questionnaire shows, the most common questions were closed, and many of them had several standardised answers to make data tabulation simpler and facilitate the process of completing the questionnaire.

One point to be taken into consideration is that the questionnaire consists of three battery questions, which are organised to be answered sequentially according to the answer given to the question in the previous sequence, in order to further examine the information given, in line with the sequence of answers. The questions gather information about three main blocks of the questionnaire, which are: the health promotion programmes completed between 2015 and 2018, the health promotion programmes carried out in 2019 and health problems that require management based on health promotion.

Finally, there were four evaluation questions, which are designed to obtain information on how the respondent feels about a series of items or aspects, to provide us with a qualitative assessment. Likert scales were used for this process, to measure the positive or negative response to a declaration. Five point scales were used on this occasion. The questions provided the nursing staff's level of satisfaction and usefulness of the health promotion programmes at their prison. It should also be mentioned that the questions followed a logical sequence from one to another and went from general to more specific questions in order to achieve the best response rates.

Description of procedure

Contact was established with the medical director and the deputy of the prison primary healthcare team (PPHT) of Figueras, to present them with the study and ask for their collaboration, for subsequent assessment by the Catalonian Health Institute and for it to facilitate information about the regional nursing staff and their corporate mail addresses. Thanks to this process the necessary contacts were established to carry out the field work.

Before sending the questionnaire, the nurse responsible for research at the PPHT of Figueras was contacted and a survey was organised with all the facilitators of the nine prisons included in the study. The objectives of the study were explained at the meeting, and the participants were asked to collaborate in transmitting the information to their nursing colleagues so as to gain the largest possible number of participants. They were also notified of the date when the questionnaire would be sent (mid-February 2020).

An e-mail message was sent all the prison nurses participating in the study with information and an explanation about the research, an informed consent and a link to the online questionnaire. a margin of two weeks was given to answer the questionnaire. Given that there was little participation, it was re-sent, with a request for the greatest possible participation, and another two weeks margin was given. Finally, the data was gathered from 15 February to 15 March 2020, which was then exported to an Excel spreadsheet for statistical analysis. The informed consents were kept under conditions of strict confidentiality. Once the questionnaire was designed, it was entered in the Google Forms program to create direct access via a and facilitate the process online for the participants. The program also made it easier to gather the data and dump it in an Excel spreadsheet for processing.

Statistical analysis

The data was entered on an Excel spreadsheet. The Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) v. 2019 was used for statistical analysis of the study.

The study variables corresponding to the nursing professionals included the ones related to socio-demographic information and to specific features of health promotion in prisons: age, sex, prisons, years since nursing studies were completed, type of nursing studies, higher education studies in health promotion, years worked as a prison nurse, work on health promotion when healthcare was managed by the Department of Justice, health promotion programmes carried out between 2015 and 2018, health promotion programmes completed in 2019, number of health promotions, instigators of health promotion programmes, issues covered in health promotion programmes, satisfaction level, level of utility, evaluation of prison setting for implementing health promotion programmes, facilities/strong points of the prison setting for health promotion, barriers/difficulties of the prison setting for health promotion, health problems that require management based on health promotion and type of health problems that should be treated with health promotion.

An initial descriptive study was carried out, using measures of central tendency such as the mean and standard deviations for the quantitative variables. A comparison was then made between the quantitative variables by determining Spearman's correlation coefficient and a linear regression model was established between the dependent variable (operational time of the prison) and the independent variable (number of health promotion projects). The considerations regarding the significance of the variables were explained (p <0.05). Finally, the Likert scales were used to assess the level of satisfaction and utility of the health promotion programmes, obtaining medians which were evaluated and interpreted.

Ethical considerations

This study complies with current legislation on ethics.

Approval of study: the study was approved the Research Ethics Committee of the Jordi Gol i Gurina University Institute for Research into Primary Healthcare on 4 March 2020.

Confidentiality of information: no data is shown about the professionals who participated in the study and Organic Law 3/2018, of 5 December, on Protection of Personal Data and Guarantees of Digital Rights, and the EU General Data Protection Regulation were complied with.

Right to privacy: no data about the professionals who participated in the study was shown.

Protection of patients: no experiments or tests were carried out in the study.

Informed consent: in accordance with the basic principles of the Helsinki Declaration, all the participants were informed about the study and its implications for research. The study included an informed consent that gave authorisation to form part of same, along a declaration that the questionnaire was completed on a voluntary basis and with complete anonymity.

Results

Participation in the study was 29.3% of the total population. Only 29 of the 99 nurses answered the questionnaire.

We found that all the male participants were diploma holders and corresponded to 11% of the professionals with this qualification. There were two female graduates, which corresponded to 6.89% of the participants. Women were represented in all the prisons except for Mas d'Enric. Only 10.34% of the participants were male and worked in Mas d'Enric and Puig de les Basses prisons. Most of the male and female nurses who participated in the study were in the 41-50 age group, most of whom had completed their studies some 15-25 years ago. Almost all the participants are diploma holders and only 7.69% of the female nurses were graduates. All the male nurses and the vast majority of the female nurses had taken postgraduate studies.

Most of the participants declared that they had done a health promotion programme at the prison where they worked in the last five years, while all the men and 92.3% of the women felt that prisons were a good setting for implementing projects or programmes based on health promotion.

As regards health promotion and the programmes promoted in Catalonian prisons in the last five years, 82.8% of the participants stated that a health promotion project had taken place at the prison where they work. On the other hand, 17.2% stated that no project had taken place at their prison.

Most of the nurses answered that they had carried out one or two health promotion projects in the last five years at the prison where they worked.

The results for the organisation that furthers such projects and programmes in Catalonian prisons showed that most of the health promotion programmes (51.5%) were imposed by the Department of Health and only 13.8% were organised at the initiative of the prison itself.

The health promotion programmes for each prison are the ones described in Table 1.

Table 1. Health promotion programmes at each prison.

| Puig de les Basses | Brian 1 and 2 |

|---|---|

| Healthy habits/mental health; HIV/STD; Smoking/drug use; Tuberculosis; Cardiovascular diseases; Hepatitis C | Diabetes; HIV/STD; Smoking/drug use; Cardiovascular diseases; Hepatitis C |

| Lledoners | Quatre Camins |

| Healthy habits; Smoking/drug use | Diabetes; Healthy habits; HIV/STD; Smoking/drug use; Tuberculosis; Cardiovascular diseases; Hepatitis C |

| Ponent | Mas D'Enric |

| Diabetes; Healthy habits; HIV/STD; Tuberculosis; Cardiovascular diseases; Hepatitis C | Healthy habits; Smoking/drug use |

| Dones de Barcelona | |

| Healthy children. | |

Note: STD: sexually transmitted disease; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus. Source: complied by authors.

The healthy habits/mental health programme is the one most commonly used in prisons, closely followed by the tobacco/drugs programme. The one least frequently repeated is the healthy child programme, which for obvious reasons is only offered at the Women's Prison of Barcelona. According the participants, the prison with the largest number of programmes is Quatre Camins.

The level of satisfaction (valued on a numerical scale from 1 to 5, with 1 being the lowest level and 5 the highest) showed that the perception of nurses when carrying out health promotion programmes is mainly 3 or more (75.8%), with level 3 being the most frequent answer amongst the respondents (31%). The level of satisfaction of the respondents was 3.36, with a standard deviation of 1.254. This score implies that most participants are not very satisfied with the health promotion programmes carried out at their prison.

The nurses' perception of the level of usefulness (valued on a numerical scale from 1 to 5, with 1 being the lowest level and 5 the highest) when they carry out the health promotion is medium, at 3 or more (79.2%), with level 3 being the most frequent answer amongst the respondents (31%). The average perceived utility of the health promotion programmes was 3.46, with a standard deviation of 1.261. This score implies that most professionals considered the health promotion programmes in their prison to be quite useful.

The elements that may interfere in the implementation of health promotion programmes in the prison setting are shown below in four blocks: elements linked to prison conditions (regimented system, staff shortages and lack of suitable spaces), ones linked to prison staff (do not prioritise health promotion activities, heavy workload and poor motivation), ones linked to the prison medical staff (heavy workload, health promotion activities are not prioritised and difficulties in forming and working with multidisciplinary teams) and finally elements related to the inmates themselves (poor adherence to the programmes, lack of interest and motivation with regard to health and lack of collaboration).

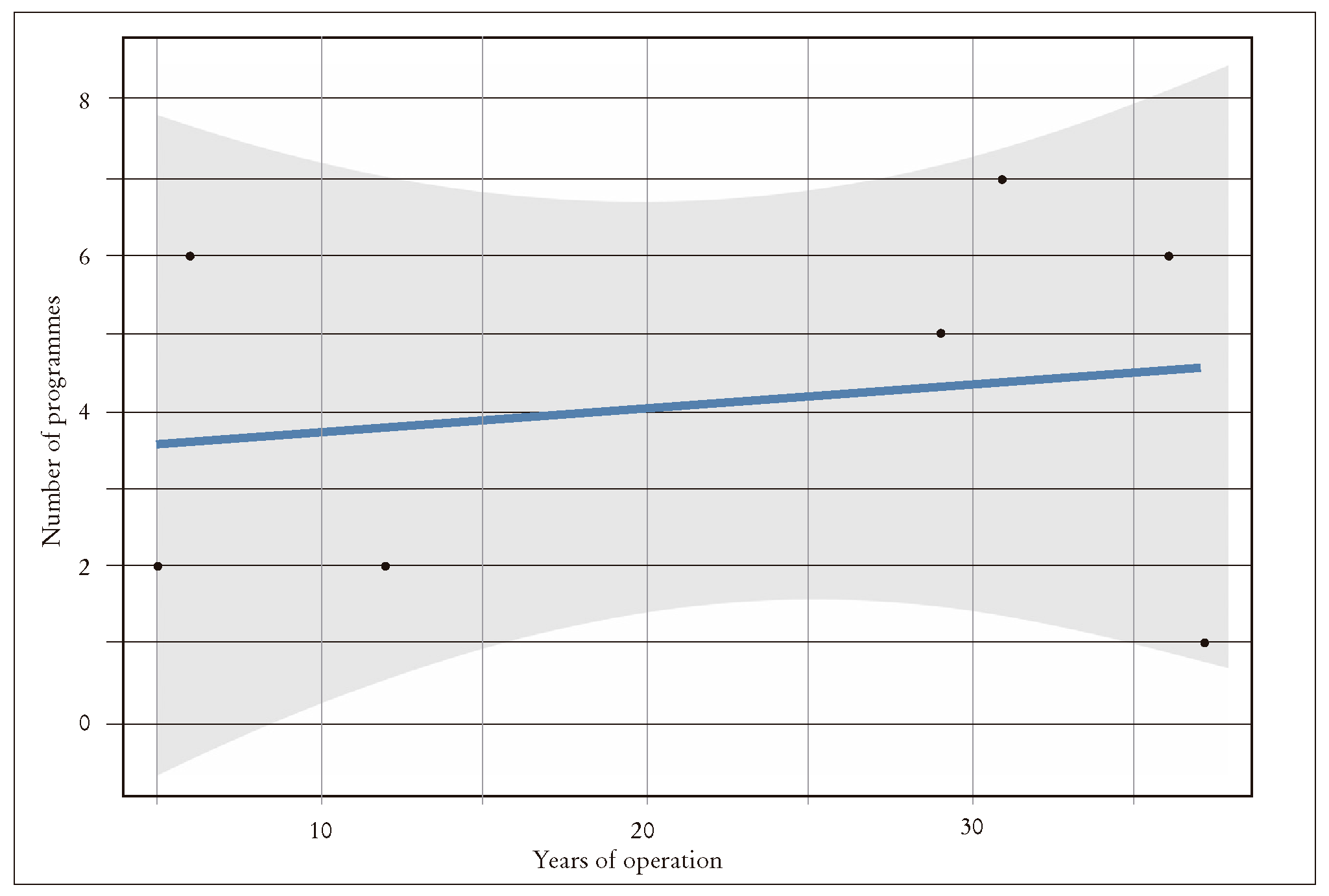

To establish the relationship between the operational time of the prison and the number of health promotion projects, a correlation and linear regression study was carried out with the operational data in years and the programmes. When the correlation study (Spearman) on the variables was completed, a value of 0.190 was obtained. This value is very low, which may imply that there is not a very strong relation between both characteristics. An hypothesis test was carried out to verify the actual relationship between the two variables in which the significance was calculated, given that otherwise this result could be due to random factors. The outcome was a value of 0.6838, and therefore the correlation was not considered to be significant.

Even after obtaining these results, another linear regression study was carried out to achieve a model that might explain the linear relation between the two variables if such a one exists. As we guessed in the previous correlation results, there is no significant linear relation between the number of programmes and the years that the prison has been operating (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Linear regression Graph of linear regression between the time variables of the time the prison has been operating and the number of health promotion programmes that take place there.

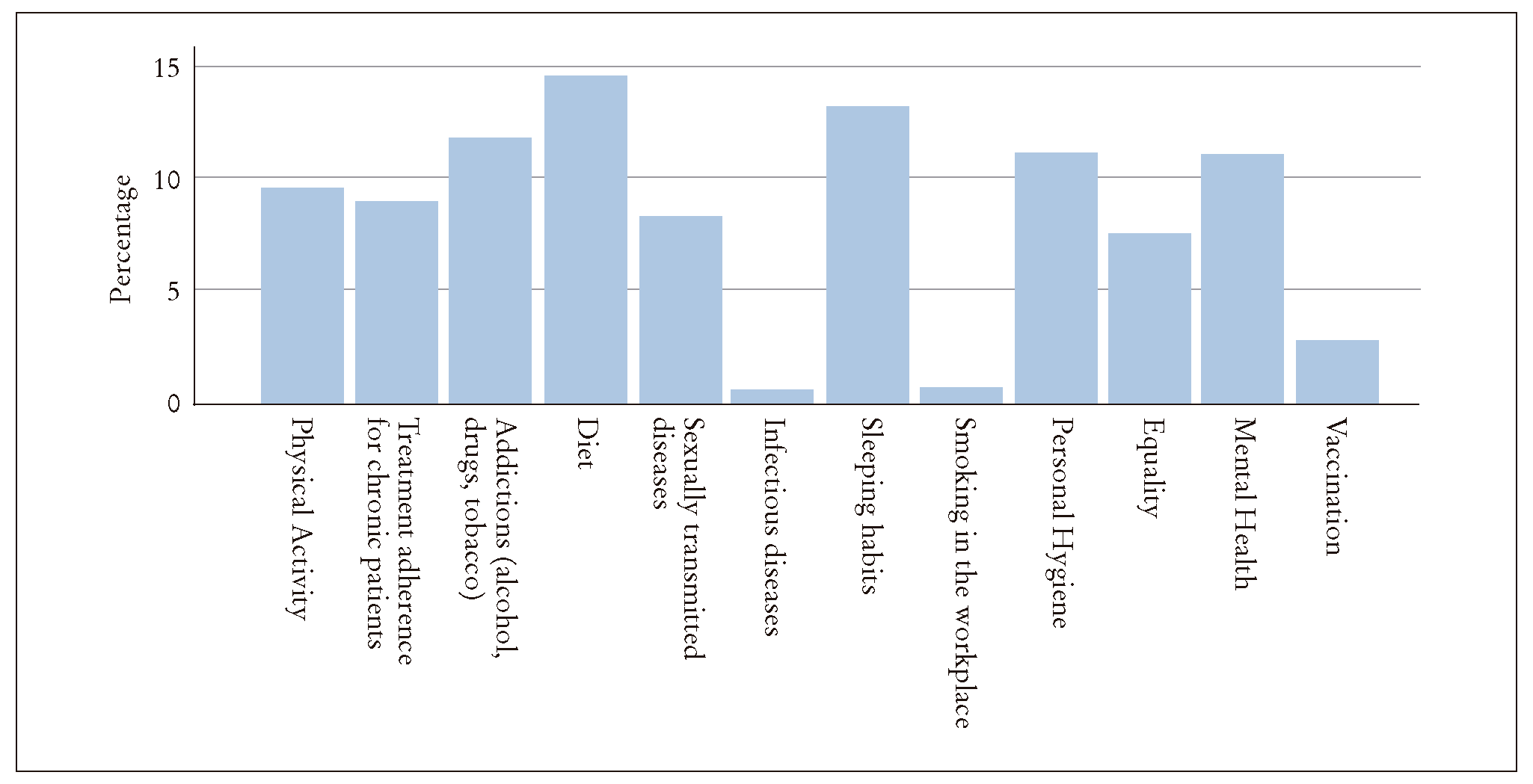

One final result is that 86.2% of the participants believe that there are health problems that prisons do not manage from a health promotion perspective. These are diet and sleep habits, with 14.5 and 13.1%, respectively (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

Certain features of prison life can be beneficial for an inmate's health, such as stability, control of times, limitations on drug and alcohol abuse and access to medical professionals. Prisons carry out early screenings and diagnoses of a range of diseases; thus making imprisonment a good moment to treat people who would most likely otherwise not go to a doctor for diagnosis or treatment. In fact, for many inmates prisons are often the gateway to normalised use of the national health system.

On the other hand, the prison setting can also be a source of many adverse effects on physical and mental health. However, imprisonment should also be regarded as an opportunity and a strategic setting to detect health problems where efforts can be made to reduce high risk behaviours in this vulnerable group9.

The Spanish prison system has shown real interest in providing services that improve the inmates' quality of life, including better healthcare and approaches that can prepare them for life outside prison, which highlight the need for educational action that focuses on promoting and maintaining healthy habits and behaviours, and an adequate use of preventive and treatment services9-11.

Authors such as Del Pozo-Serrano and Añaños-Bedrinana state that nowadays socio-educational action should be based on a participative model, and the approach taken by public health is towards community participation, equality and reduced social inequalities in health. Therefore, health promotion in prisons is a good example of intervention to reduce such inequalities. This process should be based on personal skills and the importance of overcoming social barriers12.

The principal mission of prisons, apart from serving sentences, is social rehabilitation and reintegration. A healthy prison programme can have an important collaborative role in bringing this about. The beneficiaries of such an approach would be the inmates, their families and prison staff while the long term social impact could be considerable13.

Law 33/2011, of 4 October, on Public Health, provides the current legislative framework for developing health promotion practices in Spain, and highlights the changes in social, environmental, economic and labour conditions required to encourage an impact on health; actions in different settings and through networks; the introduction of quality criteria and recognition of good practices; and the participation of citizens, either directly or via social organisations, in programmes or interventions. However, authors such as Paredes-Carbonell comment that to make this a reality, it would be necessary to systematise health promotion activities bases on theories and models of intervention that have shown themselves to be effective and that are based on contrasted evidence and experiences14.

We personally agree wholeheartedly with this idea, given that health promotion programmes designed for the general public are used in prison settings, which is the reason why they fail or have little impact.

To make our objective of creating healthy prisons a reality, it is necessary to design and evaluate the health promotion programmes, bearing in mind the special characteristics of the setting and placing particular focus on the health priorities of the prison population.

This study has shown that nurses' levels of satisfaction and utility regarding the health projects promoted at their prisons are not especially high; the average perception is not very satisfied and they are not felt to be very useful.

There is little in the way of literature about health promotion strategies in Spanish prisons. However, some previous studies were found, such as "Design of graphic materials as educational tools for health in the women's module of Zuera prison", by Arroyo, Esteban and Duato, written in 2005. The study consisted of a health education programme in the women's module15. Another was "Health education in prisons: evaluation of an experience with diabetics", by Minchón-Hernando, Domínguez-Zamorano and Gil-Delgado, written in 2009, which gave a positive assessment of a health promotion strategy for persons with diabetes and showed that there was a high degree of commitment by patients to participate in future actions of this nature at Huelva prison16. Finally, there are two studies carried out in 2016, one by Martínez-Delgado and Ramírez-López, entitled "Health education intervention in cardiovascular diseases at Soria prison"17; and another by Maestre Miquel, Zabala-Baños, García and Antolín, called "Health education for problems prevalent in the prison setting, project at Ocaña I", where a pilot health education programme was developed for inmates of Ocaña I prison. The programme was very positively received by the participants18.

Health education is a highly effective tool for promoting healthy habits and disease prevention in prisons, and so such tools clearly need to be integrated into the core structure of health promotion strategies, along with monitoring studies to evaluate their effectiveness.

Initiatives of this kind should encourage us to progressively implement this working methodology in prisons and also to pursue greater autonomy within the nursing profession, gradually changing a system that at present is mainly based on a "medicalisation" of healthcare in the prison setting2,19. The current situation continues to be one of the main barriers or limitations facing nursing staff when they work in prisons, many of whom feel that the "non-prioritisation of health promotion activities" is often one of the main reasons why they are not carried out in prisons.

Finally, it should be pointed out that there is little awareness amongst health professionals outside prison of the work done by prison nurses, who play a secondary role in the health sector. Prison nurses may defined as "specialists unknown by society, with limited human and technical resources who treat unique patients, given that not only are they all serving prison sentences, but also that a growing number of them suffer from mental illnesses, drug dependencies and infectious diseases". These special characteristics of the population and the prison setting in turn make the prison nurse a special figure20.

One of the limitations of the study is the retrospective design, which means that it only provides information about the past. Another limitation is imposed by the use of an online program for sending the survey and gathering the data, which led to low participation by the study population. Finally, there is another information bias given by the staff working when the information is gathered, since it may change as a result of sick leave, holidays or for other reasons. At the start of the study, the first decision made regarding the bibliography was to use the most recent publications, but when it was found that there were very few studies, that the subject matter was very specific and that there was little published scientific evidence, the revision was carried out with no time limit, in order to find the most relevant articles in terms of the information about the subject being studied.

The challenge of this type of project revolves around the principle of equality in public health and the development of new health promotion strategies for a highly vulnerable population. One new feature of this study is that health promotion strategies are now being developed in Catalonian prisons, although it has also brought to light the absence of this approach in many other health issues.

Health promotion strategies have been carried out in prisons, but they are basic and insufficient, and are regarded as unsatisfactory (but useful) by nursing professionals. This leads us to conclude that more work needs to be done to improve this area.

Many of the health promotion initiatives are developed by the Department of Health and the most common ones are mental health and tobacco and drug cessation programmes. It should also be mentioned that many of the health promotion programmes organised by this department are usually designed for the general public. The particular characteristics of such programmes often lead to low results or failure when they are used with the prison population.

Finally, the operating time of the prison is not linked to the number of health promotion projects that take place there. One proposal therefore would be to introduce actions on health promotion policies that focus more on prisons. This work could act as a starting point for other prison nursing professionals who are interested in professional development to continue with this line of work and above all start to development health promotion programmes designed for the prison setting and for inmates, The entire process would be suitably monitored and then evaluated, given that we can only defend such important work in this field with the right scientific evidence.

We believe that not only would this benefit the patients who participate in such programmes, but that it would also facilitate the development of the nursing profession in the prison setting, and improve the skills needed to deal with the medical challenges that time and circumstances impose. It would also strengthen our motivation and by doing so further develop our work in prisons.