Introduction

Psychological well-being refers to one's degree of optimal positive functioning. It allows personal potential and abilities to develop, and follows people's perceptions and the meaning they give to their own life circumstances (Keyes et al., 2002). Regarding life events, traumatic and stressful events promote positive change and personal growth in some people (see Tamiolaki & Kalaitzaki, 2020; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). Trauma seems to lead to an act of introspection that allows individuals to ascribe meaning to what happened and to battle their emotional distress (functional–descriptive model; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). In some people, this act of internal observation in the face of a traumatic event yields not only a considerable sense of strength and personal growth, but also increased social growth. This process results in deeper relationships with others, spiritual growth, and a greater appreciation for life (Tamiolaki & Kalaitzaki, 2020).

Recently, the National Health Commission (Huang et al., 2020) determined COVID-19 to be an infectious disease that affects not only physical health, but also negatively impacts mental well-being (e.g., restlessness, distress, fear of transmitting the virus, isolation, or negative reports in the media; Bo et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020). COVID-19 is increasing people's concerns for their own health and that of their loved ones (Li et al., 2020; Sandín et al., 2020). Infection is a vital event of great relevance that can cause posttraumatic stress (Liu et al., 2020). For instance, Liu et al. (2020) performed a cross-sectional study (N = 285) and reported that a significant number of residents of the most affected regions of China experienced posttraumatic stress. Participants suffered from the traumatic event itself, as well as hyperarousal, negative mood, or cognitive changes. This disease is influencing awareness one's own mortality and changing people's priorities (Li et al., 2020). During the SARS-CoV epidemic, Lau et al. (2006) demonstrated by means of a cross-sectional study (N = 818 Hong Kong residents) that in addition to negative mental health consequences (e.g., anger, helplessness, feelings of worry, sleep problems, or isolation), individuals also reported positive effects. Among them, increases in personal growth, social or family support, and favorable lifestyle changes stood out.

Self-forgiveness is defined as a psychological mechanism through which an offender acknowledges and accepts responsibility for their transgression, decreasing their self-resentment and increasing benevolence toward themself (Pelucchi et al., 2013). Hurting or offending others during the course of life is unavoidable, and ranges from offenses that are considered minor (e.g., speaking harshly to a loved one during an argument; Cornish & Wade, 2015) to acts of greater severity (e.g., use of violence in a conflict; Vargas et al., 2013). In this regard, forgiving oneself can result in greater psychological well-being, as previous research—mostly of a correlational nature—has strongly supported (Cornish & Wade, 2015; Fincham & May, 2019). Self-forgiveness is associated with positive potential outcomes such as improved mental health (e.g., Peterson et al., 2017; Toussaint et al., 2017), greater flexibility and emotional stability (e.g., Bem et al., 2021; Hodgson & Wertheim, 2007; Watson et al., 2012), higher levels of self-esteem and self-confidence (Pandey et al., 2020; Woodyatt & Wenzel, 2013), and greater personal growth and life satisfaction (e.g., Gilo et al., 2020; Thompson et al., 2005; Woodyatt et al., 2017). These associations have been demonstrated in the final stages of life (Kurkowski et al., 2018), as well as against diseases with different degrees of severity, such as HIV or cancer (Mudgal & Tiwari, 2015; Toussaint et al., 2014), and in survivors of complex trauma (e.g., combat scenarios; Worthington & Langberg, 2012).

The situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic presents some characteristics that are similar to assessments of cancer and HIV: COVID-19 is an infectious, transmissible, and sometimes deadly disease associated with stigma, acute fear, and a sense of hopelessness and uncertainty (Bo et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Mudgal & Tiwari, 2015). Given that self-forgiveness plays a role in resilience in the face of the counterproductive aftermath of negative life events (Bryan et al., 2015) and is associated with greater psychological well-being, we expect self-forgiveness to occur during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Compassion is a heartfelt and conscious response to the suffering experienced by others (Goetz et al., 2010). It involves a genuine desire to care for others and relieve their discomfort (Goetz et al., 2010; Pommier et al., 2020). Pommier et al. (2020) suggested that compassion is made up of four dimensions: a) mindfulness: a willingness to pay attention and listen to those who suffer; b) common humanity: the recognition that all people can experience difficulties, and a sense of connection with those who suffer; c) indifference: a form of disconnection from others' suffering; and d) kindness: concern for others' suffering and the desire to support those who need help most. Thus, the suffering of others—especially those in vulnerable groups (e.g., malnourished children or homeless people; Oveis et al., 2010)—has been specified as the generic trigger of compassion (Goetz et al., 2010; Rudolph et al., 2004).

Correlational and experimental studies that generated stimuli depicting others' suffering have associated various stimuli with greater compassion and sympathy for others: observing that other people feel pain when receiving shocks (Batson et al., 1983), listening to hospitalized patients cry out for help (Batson et al., 1997), or watching videos about children with disabilities (Eisenberg et al., 1988). In this sense, Aristotle (ca. 350 B.C.E./1991), in his Rhetoric, had already determined that the severe suffering of others (known in Greek as eleos) is a substantial precedent for compassion. Furthermore, Aristotle (ca. 350 B.C.E./2004) pointed out that compassion is aroused not by suffering itself, but by undeserved suffering, compassion becoming metaphorically known as the "guardian" of undeserved suffering (Goetz et al., 2010; Haidt, 2003).

Primarily through experimental and intervention studies (e.g., López et al., 2018), psychologists have found that compassion for others faced with external situations that are painful and difficult to cope with (e.g., dealing with sex offenders; Giovannoni, 2017) is associated with positive outcomes for others and for oneself (Jazaieri et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2021). Compassion helps maintain one's sense of common humanity (Giovannoni, 2017) and increases positive affect (Sprecher et al., 2007), personal growth, and life satisfaction as a result of providing care for and support to others (Watson, 2018; Wayment et al., 2015). Thus, compassion for others seems to be associated with great psychological strength, given full awareness of others' needs and suffering (Baer, 2010; Lee et al., 2021; López et al., 2018; Neff & Seppala, 2017).

The COVID-19 pandemic is a unique situation that is generating malaise in the population on a large scale (Sandín et al., 2020). This suffering can be considered undeserved because it fundamentally disadvantages vulnerable groups: higher mortality rates have occurred among older adults and people with previous pathologies such as cardiovascular diseases or chronic respiratory diseases, among others; for further review, see Shahid et al. (2020). Thus, suffering from COVID-19 triggers compassion toward others (see Goetz et al., 2010; Rudolph et al., 2004). This newfound compassion could promote full awareness of others' adversities and lead to positive psychological outcomes (Baer, 2010; Lee et al., 2021; López et al., 2018; Neff & Seppala, 2016). Therefore, we expected that compassion toward others should be associated with greater psychological well-being (i.e., personal growth and life satisfaction) in the era of COVID-19.

Although empirical evidence to date on the role of self-forgiveness in compassion for others is quite scarce—even more so in critical situations—qualitative evidence has suggested that practicing self-forgiveness is a critical part of developing compassion for others (Giovannoni, 2017). Along these lines, Neff and Pommier (2013) reasoned that the ability to forgive oneself and accept one's own imperfect humanity is also used to forgive others. Correlational research (e.g., Hill & Allemand, 2010) has indicated that self-forgiveness is associated with more positive interactions with others. Similarly, forgiveness for others is related to greater self-compassion (Matsuyuki, 2011; Sakiz & Sariçam, 2015); self-compassion requires self-forgiveness and a willingness to exercise benevolence (Neff, 2003). Thus, it is possible to conjecture that despite the lack of empirical studies on the relationship between self-forgiveness and compassion for others, as well as the possible mediating role of compassion for others in self-forgiveness and psychological well-being, there is evidence to the contrary that reveals self-compassion mediates the association between forgiveness for others and psychological well-being (Matsuyuki, 2011). As mentioned, people's levels of awareness and priorities seem to be changing due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic—uncertainty, loss of loved ones, undeserved suffering, and impacts on the most vulnerable people (Li et al., 2020; Sandín et al., 2020; Shahid et al., 2020). Forgiving oneself after committing an offense could be associated with greater compassion for others, ultimately resulting in positive psychological consequences by fostering awareness of other people's misfortunes.

Our Study

Considering the abovementioned points, we aimed to explore the roles of self-forgiveness and compassion in psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we examined self-forgiveness and compassion for others (i.e., mindfulness, kindness, indifference, and common humanity) in relation to personal growth and life satisfaction. We expected that (a) self-forgiveness should be positively associated with compassion (Hypothesis 1a), personal growth (Hypothesis 1b), and life satisfaction (Hypothesis 1c); (b) compassion should be positively related to personal growth (Hypothesis 2b) and life satisfaction (Hypothesis 2b); and (c) self-forgiveness should be associated with greater personal growth and life satisfaction via compassion (Hypothesis 3a and Hypothesis 3b, respectively).

Method

Participants

Our initial sample consisted of 433 Spanish participants from the general population (76 men and 280 women) aged between 18 and 83 years (M = 32.05, SD = 13.29). Using G*Power (Version 3.1.97), we estimated 197 participants were needed to perform a correlation test with a medium effect size of d = .25, a significance level of α = .05, and a power of .95. Seventy-eight participants were excluded from analyses because they did not complete the full questionnaire or because their comments indicated that they did not respond seriously to the description of the offense requested in the study. In addition, we removed 26 participants whose scores were below the established criteria for assuming offense responsibility (Pelucchi et al., 2013, 2015). Thus, the final sample was composed of 329 participants from the Spanish population (72 men and 257 women), who ranged in age from 18 to 83 years (M = 31.31, SD = 12.84). Of this sample, 43.5% were employed, 42.9% were college students, 11.2% were unemployed, and 2.4% were retired.

Procedure and Design

Participants voluntarily completed the online questionnaire through the Limesurvey research platform, and did not receive monetary compensation for their participation. The inclusion criteria to participate in the study were being of legal age and of Spanish nationality. The research was disseminated by the primary researchers through their private accounts on different social networks (Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram). Before completing the questionnaire, participants were informed that the purpose of the study was to examine "psychological and relationship aspects that may be affected due to the COVID-19 situation." They were also informed about the anonymity of their responses, ensuring confidentiality in the processing of their data. According to the Declaration of Helsinki, the participants checked the box with the following statement: "I agree to participate in this study." The study was conducted with approval from the Ethics Committee of [blinded for review].

First, participants responded to measures of compassion, personal growth, and life satisfaction after being instructed to consider the lockdown situation. Next, we asked participants to briefly describe an offense they had committed against another person prior to the lockdown period (which started in Spain on March 14, 2020, with 5,753 positive cases and 136 deaths; Spanish Ministry of Health, 2020). Finally, we asked participants about their degrees of self-forgiveness and present feelings of responsibility for their offenses.

Measures

Compassion Scale

The Compassion Scale (Pommier et al., 2020) is composed of 16 items structured in four dimensions assessing others' general life suffering: mindfulness (four items; e.g., "I listen patiently when people tell me their problems"), kindness (four items; e.g., "I like to be there for others in times of difficulty"), indifference (four items; e.g., "I think little about the concerns of others"), and common humanity (four items; "I feel that suffering is just a part of the common human experience"). We adapted the Compassion Scale to measure the degree of compassion elicited by the COVID-19 pandemic: "We ask you to consider the confinement situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and think about how you are with others." We performed a translation and back-translation process (English–Spanish/Spanish–English) per Wild et al. (2005). This measure had a Likert-type response format with five response options, ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The original measure revealed adequate psychometric properties, showing an internal consistency fluctuating between .69 and .75 for mindfulness, between .63 and .85 for kindness, between .67 and .84 for indifference, between .66 and .75 for common humanity, and between .77 and .90 for the full scale (Pommier et al., 2020). The Cronbach's alpha coefficients obtained in this study were mindfulness, α = .67; kindness, α = .68; indifference, α = .62; common humanity, α = .49; total scale, α = .75.

Psychological Well-Being Scale

To measure psychological well-being, we used the personal growth subscale of the Psychological Well-Being Scale (Ryff & Keyes, 1995; Spanish adaptation by Díaz et al., 2006), which consists of four items (e.g., "When I think about it, I haven't really improved much as a person over the years"). Participants were asked to consider the self-confinement situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and respond on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). The subscale has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties in the Spanish context (α = .68; Díaz et al., 2006). For this study, we obtained α = .76 for the personal growth subscale.

Satisfaction With Life Scale

The Satisfaction With Life Scale consists of five items assessing global cognitive judgments of satisfaction with one's life (Diener et al., 1985; Spanish version by Atienza et al., 2000; e.g., "So far, I have gotten the important things I want in life"). To respond to this scale, the same instructions were followed as for the personal growth subscale. The response format for this measure was a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). This scale also has adequate internal consistency among the Spanish population (α = .84; Atienza et al., 2000). In our sample, we obtained α = .90 for this scale.

Offense Description

Using the critical incident technique (Flanagan, 1954), participants were asked to describe an offense they committed against another person before the beginning of the quarantine period.

Responsibility

As in previous studies (Pelucchi et al., 2013, 2015), we used an item to assess the degree of responsibility ("To what extent do you feel responsible for the offense, considering the current confinement situation?"), rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = I do not feel responsible at all to 7 = I totally feel responsible).

Self-Forgiveness

We also included one item to measure participants' degree of self-forgiveness ("To what extent has the current situation favored your forgiving yourself after the offense was carried out?"), rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = It has not favored me at all to 7 = It has totally favored me).

Analysis Strategy

First, the autobiographical stories about the participants' offenses were analyzed by two coders, who carefully read the participants' descriptions and generated a preliminary coding system. Then, after detecting common elements in the participants' descriptions, different categories were established. Subsequently, the two coders compared the preliminary coding system they had developed and created a definitive general coding system. A similar procedure was followed in a study by Navarro-Carrillo et al. (2017).

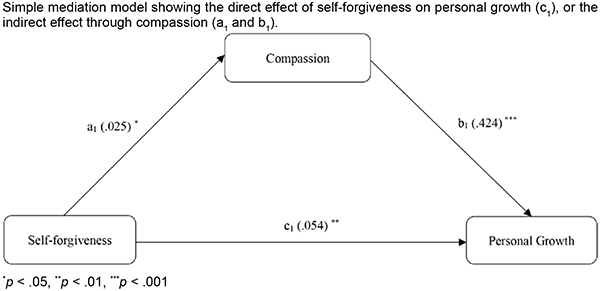

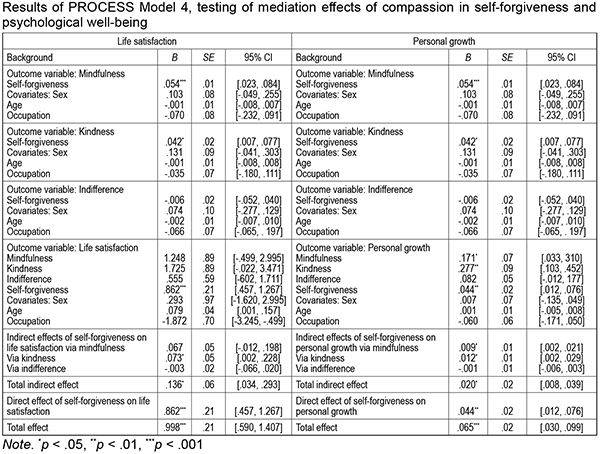

Next, to test the research hypotheses, we carried out a point-biserial correlation analysis to observe the way in which the study variables were associated (see Table 1). Ultimately, to determine whether compassion mediates the relationship between self-forgiveness and psychological well-being (personal growth and life satisfaction), we performed several multiple mediation analyses using Model 4 of the PROCESS macro program (Version 3.4.1; see Table 2, Figure 1). Sex, age, and occupation were included as covariates.

Results

Interpersonal Offenses

Participants reported a wide variety of interpersonal offenses they had committed. Specifically, 42.6% reported having offended a family member (e.g., insulting parents, mother, or siblings), 21.6% had offended their partner or ex-partner (e.g., accusing the partner of being unsupportive or unfaithful), 21.6% had offended a friend (e.g., revealing intimate details or secrets), 3% had offended classmates or coworkers (e.g., bullying or hiding important work-related information), and 11.2% reported offenses without specifying the person they had offended (e.g., yelling or being disloyal).

Associations among Self-Forgiveness, Compassion, and Psychological Well-Being

To examine whether self-forgiveness was positively related to compassion for others, personal growth, and life satisfaction (Hypotheses 1a, 1b, and 1c, respectively) and whether compassion was positively associated with personal growth and life satisfaction (Hypotheses 2a and 2b), we conducted a point-biserial correlation analysis. As seen in Table 1, self-forgiveness was positively associated with compassion (dimensions of mindfulness, kindness, and total compassion; Hypothesis 1a) and was positively related to personal growth and life satisfaction (Hypotheses 1b and 1c). This indicated that forgiving oneself after committing an offense is associated with higher levels of compassion for others and with a greater sense of personal growth and satisfaction with life during the COVID-19 quarantine period. Likewise, compassion (except in the indifference dimension) was positively related to personal growth (Hypothesis 2a) and satisfaction with life (Hypothesis 2b), indicating that higher levels of compassion for others are associated with higher levels of psychological well-being (personal growth and satisfaction with life). These results supported Hypotheses 1 and 2.

The Mediating Role of Compassion in Self-Forgiveness and Psychological Well-Being

To test the effect of self-forgiveness (Hypothesis 3a) on personal growth and life satisfaction (Hypothesis 3b) via the dimensions of compassion (mindfulness, kindness, and indifference), we performed various multiple mediation models (PROCESS macro Model 4). To this end, we followed MacKinnon et al.'s (2004) recommendation, using a nonparametric bootstrapping procedure with 10,000 replications to estimate a 95% confidence interval (CI). We included the sociodemographic variables mentioned in the previous section as control variables.

Regarding life satisfaction, the variables included in our model predicted 14.3% of the variance for the inclination to show satisfaction with life. However, as seen in Table 2, significant indirect effects were obtained only in the compassion dimension when referring to kindness. That is, self-forgiveness was indirectly linked to greater life satisfaction through its effects on increased kindness (B = .073, SE = .05, 95% CI [.002, .228]). We repeated the mediation analysis with the compassion measure as a combined scale (PROCESS Model 4, simple mediation analysis). The indirect effect was significant, indicating that self-forgiveness was indirectly linked to greater life satisfaction through its effects on increased compassion (B = .060, SE = .04, 95% CI [.005, .176]; see Figure 1). In addition, the total effect of self-forgiveness on life satisfaction was significant (B = .998, SE = .21, 95% CI [.590, 1.407]). Age (B = .083, SE = .04, 95% CI [.004, .162]) and occupation (B = -1.895, SE = .71, 95% CI [-3.290, -.500]) affected life satisfaction when included as covariates. In other words, older people and employed people (Memployed = 25.60, SD = 6.13; Mcollegestudents = 23.53, SD = 6.95; Munemployed = 18.38, SD = 8.08; Mretired = 19.50, SD = 8.37) reported higher levels of life satisfaction.

Figure 1. Simple mediation model showing the direct effect of self-forgiveness on life satisfaction (c1), or the indirect effect through compassion (a1 and b1).*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

In relation to personal growth, the variables included in the model predicted 18.6% of the variance for the inclination to show personal growth. As shown in Table 2, self-forgiveness was indirectly related to higher personal growth through its effects on increased mindfulness and kindness. By repeating the mediation analysis with the combined compassion measure, we obtained a significant indirect effect, indicating that self-forgiveness is indirectly linked to higher levels of personal growth via its effects on greater compassion (B = .010, SE = .01, 95% CI [.001, .023]; see Figure 2). The total effect of self-forgiveness on personal growth was also significant (B = .065, SE = .02, 95% CI [.030, .099]), and the covariates did not affect the model. These findings supported Hypothesis 3.

Table 2. Results of PROCESS Model 4, testing of mediation effects of compassion in self-forgiveness and psychological well-being

Note*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Discussion

We examined the roles of self-forgiveness and compassion in psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that higher levels of self-forgiveness were associated with higher levels of compassion, personal growth, and life satisfaction. Higher levels of compassion were associated with higher levels of psychological well-being, as well. On one hand, it may be possible that the ability to forgive oneself after performing a harmful behavior and assuming and recognizing that the offensive behavior might have been unfair enhanced awareness of other people's undeserved suffering during the COVID-19 pandemic. Even more so, it this might have led to developing greater feelings of compassion for the most vulnerable people and a deep desire to alleviate their discomfort. This interesting finding is in line with the previous literature, which suggested the ability to forgive oneself and accept that one is an imperfect being creates greater feelings of compassion and sympathy toward others (Neff & Pommier, 2013). On the other hand, it could be argued that the main perceptions of COVID-19 are similar to those surrounding HIV and cancer—diseases with high mortality rates that are accompanied by social stigma and feelings of fear and hopelessness (Bo et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Mudgal & Tiwari, 2015; Toussaint et al., 2014). In this regard, unresolved feelings of self-blame or self-resentment significantly interfere with an individual's optimal functioning (Toussaint et al., 2014).

Self-forgiveness is a self-awareness process for dealing with mistakes made that favors moral integrity (Kurkowski et al., 2018; Mudgal & Tiwari, 2015). For this reason, the COVID-19 pandemic could also be generating a need to move on among the global population—as in other people suffering from serious diseases. People can move on after accepting that mistakes have been made in the past; that these mistakes can be repaired in the present or the future; that nobody is perfect; and that one should try to find the good in what has gone wrong (Toussaint et al., 2014). This process of introspection and self-improvement can be achieved with self-forgiveness. In turn, the process contributes to better personal growth and existential well-being as people view themselves as more benevolent and find meaning in their offensive behavior.

At the same time, just as in other complex situations (Giovannoni, 2017; Lau et al., 2006), the population has become more aware of others' suffering caused by COVID-19 (e.g., loss of family members, friends, or partners). This can increase people's compassion for others and toward vulnerable groups, among whom suffering may now be perceived as undeserved to a greater extent (Konstan, 2004). Specifically, it appears that our study population showed greater eagerness to listen to and care for those who were suffering (mindfulness) and more concern for and desire to support those who needed help most (i.e., kindness; Pommier et al., 2020), traits which positively affect personal growth and satisfaction with life when linked to greater psychological strength (Baer, 2010; Neff & Seppala, 2017). However, more research is required to confirm these assumptions.

Ultimately, our results showed that high levels of self-forgiveness were associated with higher levels of compassion and, consequently, with higher levels of personal growth and life satisfaction. Considering the situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, this finding is interesting—forgiving oneself seems to lead to greater awareness of others' suffering and a greater willingness to listen, pay attention to, and care for them and mitigate their discomfort (Goetz et al., 2010; Pommier et al., 2020). Therefore, perhaps taking stock and accepting the offenses they have committed with a view toward better future behavior will lead to an improvement in people's well-being. In addition, this association could perhaps be tempered by the sense of injustice that the offender has about their offensive behavior and by their perception of others' suffering. However, this is the first empirical finding relating self-forgiveness to compassion for others. Future studies could replicate these findings in other situations or compare them with the postconfinement environment to see whether the effects are sustained over time and consider other latent variables, such as one's sense of justice (Pelucchi et al., 2013) or worthiness (Shahid et al., 2020).

We found it striking that older people reported higher levels of satisfaction with life. Previous studies have revealed that older adults tend to be more likely to review their personal experiences (e.g., Bohlmeijer et al., 2008; Hirsch & Mouratoglou, 1999), seem to understand the memory of positive experiences, and accept misbehaviors from the past along with resentment and feelings of guilt (Hirsch & Mouratoglou, 1999). The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., fear, uncertainty, or loss of loved ones; Li et al., 2020) may have been conducive to such recollection of personal experiences; although this may seem paradoxical, pandemic conditions may have fostered a sense of integrity, helping people find meaning and perceive greater satisfaction with their life stories (Hirsch & Mouratoglou, 1999). Future research could delve deeper into this suggestion.

Likewise, satisfaction with life was closely associated with income and employment (Kahneman & Deaton, 2010). Unemployment is associated with unhappiness and a lack of positive well-being (Gudmundsdottir, 2013). In this regard, if one looks at not only health concerns but also the economic crisis resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, a new global economic recession like the one experienced during the 2008 financial crisis is emerging (Danylyshyn, 2020). This situation can affect psychological well-being, especially in people who lack the economic support to survive. Future research could probe in greater detail how unemployment or income levels during the COVID-19 pandemic affected the global population's life satisfaction or happiness levels.

As we used a correlational methodology, we find ourselves with the limitation that the data we obtained do not allow causal relationships to be established or to be generalized to the entire population. However, our data allow us to observe the behavior of people at the present time, and they provide us with a point from which to continue investigating the current phenomenon (Stangor, 2011). Another limitation was the low reliability obtained in the common humanity dimension relative to the Compassion Scale. This could be due to some misconceptions when translating this dimension, or to the connotations that this dimension presented compared to the rest. Thus, while the dimension of common humanity focuses on more general aspects (i.e., it implies the recognition that all people can experience difficulties), the rest of the dimensions focus on individual aspects: willingness to pay attention to or worry about other people's suffering, and the desire to support those who need it most (Pommier et al., 2020). In this regard, it would be interesting for future research to delve into the significance of these dimensions and their associations with prosocial behaviors.

Similarly, because we used only one item to assess self-forgiveness, our results should be viewed with caution. Future research could replicate these results using a more robust measure of self-forgiveness focused on the situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Along the same lines, given that our study participants were mostly women and young people, future research could consider homogenizing the sample, as well as establishing different age groups to determine any differences in self-forgiveness as a consequence of experiences caused by COVID-19.

Finally, our research context focused on a sample from the Spanish population. Although self-forgiveness, compassion, and psychological well-being are considered universal constructs, our findings may not persist in other Western countries or populations of different cultures (see Goetz et al., 2010; Knight & Hugenberger, 2007; Russell, 2003). Future research could carry out more cross-cultural work to demonstrate the extent to which our findings can be replicated among the global population.

In conclusion, our study contributes to therapeutic practice by considering self-forgiveness training. Self-forgiveness interventions empower people to perceive themselves more positively, to find meaning in their offensive behaviors, and to notice their personal growth. Additionally, therapeutic practice could contemplate training people in compassion through the practice of kindness or affectionate generosity, to allow them to appreciate feelings of compassion for themselves and others. Both psychological mechanisms have the potential to decrease the levels of fear and hopelessness caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, with the ultimate goal of promoting individual well-being.