1. Introduction

Spain joined the list of countries that have decriminalized assisted suicide and allowed their citizens to put an end to their lives through medical assistance on March 24, 2021, with the passage of the Organic Law on the Regulation of Voluntary Euthanasia (LORE). The law generated mixed reactions-while some researchers observe that it is consistent with the evolution of Spanish society and with its consideration of the right to life in non-absolute terms, others believe it violates fundamental rights or even exerts pressure on elderly and disabled people to commit suicide.

In any event, LORE established a new legal framework in Spain and the number of people requesting assistance to die has indeed increased. In this sense, the Spanish medical system and governmental authorities face practical problems concerning the concrete application of the law-the legitimacy of performing euthanasia on patients with mental diseases, or the modalities and practicalities necessary and appropriate in providing the assistance to die, for example. In this regard, this article analyzes the practical extent of the legalization of euthanasia and the necessary procedures that must be developed. More concretely, we conclude that the statutory articles establishing the principal concepts of the legislation (art. 3), the physical locations where euthanasia can take place (art. 14) and the role of the medical staff with respect to these actions (art. 11) lack clarity with respect to defining the specific procedures required under the law. In this sense, we find that the law contains inconsistences concerning three main points: (a) regulation of the assistance to die for patients with mental illnesses; (b) the legality of third persons' cooperation in the self-administration of the relevant drugs; and (c) the role of medical staff in providing assistance to patients who decide to self-administrate the relevant drugs. These issues indicate that, although euthanasia is now officially recognized under Spanish law, its practical aspects require careful assessment in order to prevent confusion in its implementation.

The article is organized as follows. The first section analyses the regulation of euthanasia and cooperation in suicide from a comparative perspective. The second section focuses on the LORE in Spain and explores the particular issues that attend the provision of assistance to die in patients suffering from mental illnesses. The third section analyzes the modes of assistance to die contemplated under the law and explores the choices available to patients receiving assistance during self-administration of the relevant drugs. The fourth part of the article examines the role of medical staff in providing the assistance to die with a particular focus on the assistance that a doctor must provide when a patient chooses to self-administrate drugs. Finally, the fifth section summarizes the principal conclusions and highlights the essential problems in the content of the law.

This paper contributes to the discussion concerning the implementation of euthanasia and explores several practical issues that the law in its current form faces. We hope this would generate discussion of and momentum for subsequent clarifications that would guarantee and facilitate effective and efficient access to euthanasia.

2. Euthanasia and Cooperation in Suicide: A Comparative Perspective

Euthanasia is often a sensitive subject that generates attention from several groups, including doctors, politicians and members of religious communities. The debate concerning euthanasia among these groups is often centered around morality rather than practical considerations regarding its implementation. In general terms, euthanasia-in which a doctor administers a lethal dose of medication to a patient-and physician-assisted suicide ("PAS")-in which a doctor prescribes a drug and the patient herself takes it-are largely illegal. However, several countries have legalized one or both practices, which has generated debate over the possibility of broadening the scope of these practices to the point of considering them human rights.

Beginning in 2006, Switzerland has allowed physician and non-physician assisted suicide without a minimum age requirement or diagnosis (Hamarat et al., 2021). Although the law is certainly broad with respect to its "permissibility", it is strict concerning its implementation and permits PAS only if the interested parties' motivations are not selfish (Fischer et al, 2008; Richards, 2017; Boshard et al, 2008). While PAS is legal in Switzerland, euthanasia is not: even though the patient receives assistance, she must self-administer the drug or ingest the barbituric.

The Netherlands was the first country to legalize euthanasia in 2002. It should be noted that the Dutch law does not include the term euthanasia, but instead uses the term termination of life on demand, and does not develop an extensive definition of that term (Kouwenhoven et al., 2019). Dutch law provides that the direct and effective intervention of a doctor in causing the death of a patient suffering from an irreversible disease, or who is in a terminal phase and subject to an unbearable condition, is legal. Although the law strictly guarantees the latter, its eligibility requirements are strict. Specifically, the patient must reside in the Netherlands and the request for euthanasia or aid in suicide must be voluntary and made with reflection (Berghmans and Widdershoven, 2012).

In terms of the motivation for the request, the applicant's suffering must be intolerable with no prospect of improvement. The patient must also demonstrate an understanding of her disease and its prognosis. In addition, the doctor who will perform the euthanasia involve a partner in consulting on the case and that partner must issue a corresponding validating report (Rietjens, et al., 2019).

Similar to the Netherlands, Belgium legalized euthanasia and PAS in 2002. The requirements for eligibility in Belgium are strict. Namely, the patient must be an adult, an emancipated minor, or a minor with capacity for discernment. Second, the patient must make a voluntary, well-considered and repeated request that is not the result of external pressure. Third, the patient must exhibit a medical condition that promises no prospect of improvement. Fourth, the patient must experience constant and unbearable physical or psychological suffering that cannot be alleviated. Finally, the patient's suffering must result from a serious and incurable disorder that was caused by illness or accident (Cohen-Almagor, 2009).

A controversial issue relating to euthanasia in Belgium-and in the Netherlands and Spain-concerns the concept of psychological suffering, as the applicable statutory schemes do not specify how the difference between psychological suffering and physical suffering should be assessed. The absence of any consensus or legal guidance regarding how to define psychological suffering, for example, makes it possible to use the concept in an increasingly broad way. The Belgian law regulating euthanasia contains significantly more detail than the related Dutch law, which was primarily generated as the codification of existing regulations. For these reasons, the Belgian legislature drafted and passed detailed provisions to provide a greater level of protection and security to doctors and patients in this area (Dierickx et al., 2016; Cohen-Almagor, 2009).

In the United States, certain states (Oregon, Washington, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Hawaii, New Jersey, Vermont, Maine) and the District of Columbia permit doctors to prescribe lethal drugs for self-administration. The requirements governing this practice are generally very strict and subject to the laws of each individual state (Indabas, 2017). In Oregon, for example, individuals must have an incurable and irreversible disease that is likely to cause death within six months, the request must be made orally, followed in writing and signed by two independent witnesses, and two doctors must oversee the procedure. In Montana, doctors may assert a defense to assisting in a person's suicide under a 2009 court ruling (Young et al., 2019).

Colombia was the first country in Latin America to decriminalize euthanasia in 1997. The Colombian law allowed euthanasia only in cases of terminal illness, however, and the government did not develop a regulation to implement it until April 20, 2015. On July 22, 2021, the Colombian Constitutional Court expanded this right, allowing the procedure if the patient is subject to intense physical or mental suffering due to bodily injury or a serious and incurable disease (Downie et al., 2022).

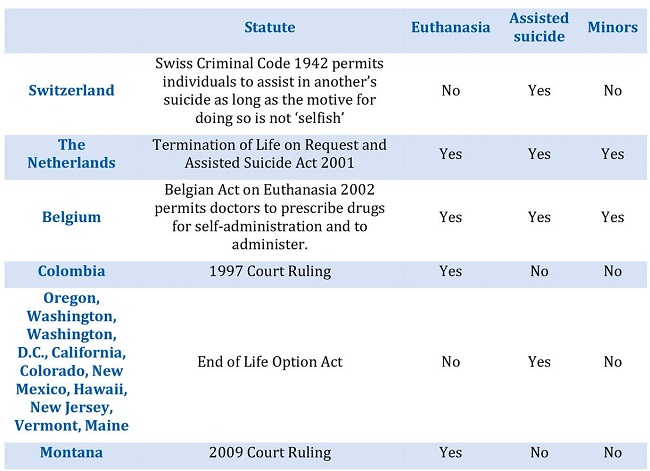

The following table summarizes the main elements regarding euthanasia and PAS in several countries/states:

In summary, the foregoing discussion demonstrates that regulations concerning euthanasia and PAS vary in extent and scope across the world. What is clear, however, is that elements such as establishing ages for requesting euthanasia or determining psychological suffering have not been revolved and, in fact, the newly approved Spanish law shows that these elements deserve special attention if the intent is to develop a comprehensive law that guarantees certain basic conditions.

3. Organic Law 3/2021, March 24, on the Regulation of Voluntary Euthanasia (LORE)

LORE was drafted in the context of a variety of rights contained in the Constitution of Spain of 1978-CE: Life and Moral and Physical integrity (art. 15 CE), Dignity (art. 10 CE), Freedom (art. 1.1 CE), Freedom of Ideology and Conscience (art. 16 CE) and Privacy (art. 19.1 CE). In this sense, during the last several decades Spain has experienced conflict among groups of citizens who claimed the existence of a free disposal to the right to life-and therefore the right to die-and those who considered that the state was responsible to protect its citizens' right to live and thereby to forbid any attempt to cooperate or produce the death of a third person.

Before LORE was approved, Spanish courts systematically rejected the legality of euthanasia-interpreted as the direct administration of a drug directed to the death of a patient-and applied article 143 of the Criminal Code (Código Penal) to prosecute purported violators for cooperation in suicide. Most of the complaints submitted to the European Court of Human Rights1 received no support, as that Court determined that, despite the fact that euthanasia may not be forbidden under the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (specially art. 2 and art. 8), it should likewise not be considered a right thereunder either-a view derived from the right to respect for private life (Sartori, 2018; Arruego, 2021).

As a result, during this period several extremely controversial cases polarized Spanish society, like the death of Ramón Sampedro-who received assistance to die after decades of being tetraplegic, Fernando Cuesta-who moved to Switzerland to commit assisted suicide and Ángel Hernández-who assisted his wife, who was suffering from multiple sclerosis, to commit suicide and was prosecuted by the Gender Violence Court (Tribunal de Violencia de Género). These cases ultimately increased the Spanish public's support for legalization of the assistance to die, which reached 72.4% in January 2021 (CIS, 2021: 20).

In this sense, LORE incorporated the right to receive assistance to die as part of the right to self-determination. Even though this law was judicially appealed to the Spanish Constitutional Court (Tribunal Constitucional) by the far-right political party Vox, on March 2023, the Court determined its constitutionality and recognized that the right to receive assistance to die is consistent with the Spanish Constitution (Cambrón, 2020; Tomás-Valiente, 2021a: 102).

In addition, while the law contemplates conscientious objection (Objeción de Conciencia) by the health professionals pursuant to article 16, some medical groups have questioned the role of the medical staff in this process. The Spanish Association of Bioethics and Medical Ethic ("AEBI"), for example, explicitly stated its disapproval of the law, particularly with respect to the protagonist role foisted upon medical staff as the primary facilitators of the assistance to die (AEBI, 2021). AEBI further supported the statement of the Spanish Medical Colleges Organization ("OMCE") in its rejection of any medical intervention directed to the end of provoking a patient's death (OMCE, 2021).

Another key aspect of the law is that it contemplates euthanasia as an exception to the crime of cooperation in suicide. Specifically, as long as the provision of assistance to die is undertaken pursuant to all the requirements established by the law, the provider of that service will not incur any legal responsibility for the resulting death and, instead, the death will be considered to have occurred of natural causes (First Additional Disposition). In fact, LORE amended article 143 of the Criminal Code by modifying paragraph 4 of that article and adding a new paragraph 5: "Despite what the previous paragraph establishes, there will not be criminal responsibility for the person causing or actively cooperating in the death of a person if fulfilling the content of the Organic Law regulating Euthanasia."2

In this sense, LORE is similar to the existing laws in Belgium and Netherlands (Velasco, Bernal and Trejo, 2022) as it recognizes both euthanasia and assisted suicide and establishes a key role for medical staff in support of those ends. This contrasts with the Swiss law, which authorizes the participation of non-profit organizations in assisted suicide. LORE establishes a myriad of requirements with respect to these rights. Juanatey notes the following elements: (a) the patient's informed consent is required (art. 3.a); (b) the assistance to die must be directed by a doctor (art. 3.d); and (c) the patient must be subject to severe, chronic and disabling suffering or a serious and incurable disease (2021: 79). Additional requirements include that the patient is a Spanish citizen, she has legal residence in Spain, or she can accredit residence in Spain for at least 12 months prior to the request; the patient is an adult and there must be a temporal delay between the two requests for assistance to die or a formal revision before its implementation.

With respect to the severe, chronic and disabling suffering requirement, some commentators have already warned of potential problems in the manner in which the law establishes the nature of the patient's suffering or disease. The relevant provision states that a patient must be "Suffering a severe and incurable disease or a severe, chronic and disabling suffering in the terms established by this law (art. 5.d).3 The law does not, however, contain specific language concerning mental disorders-i.e., severe depression or schizophrenia-and patients with these diseases may request similar legal recognition and assistance to die. This interpretation would ostensibly be consistent with the plain language of article 3 with respect to "severe, chronic and disabling suffering", which might reasonably include both physical and psychological suffering.

Even though some countries-Belgium and the Netherlands, for example- have legalized this practice, the lack of protocols and specific evaluation requirements under LORE threatens to require additional legislation or more specific legal interpretation in the courts. In fact, the Spanish Association of Psychiatry (SAP) has already proposed a procedure to address these issues, which is summarized in four questions directed to the patient that are designed to evaluate the mental state of the patient, the existence of effective medical treatments and the nature of the patient's suffering in relation to the mental disease (SAP, 2021: 15).

This issue is rooted in the existing controversy concerning patients suffering from diseases that cause cognitive impairment. In 2016, a doctor was prosecuted in the Netherlands after performing euthanasia on a patient with Alzheimer's disease who had previously manifested in writing her desire to receiving euthanasia but, when receiving the assistance to die-and with her cognitive skills severely deteriorated-refused and was subsequently forced by her family members (Miller and Kim, 2019). While the doctor was ultimately absolved in 2019, the case prompted discussion concerning how advance euthanasia directives should be treated if a patient expresses changed views at a time when her decision-making capacity is deteriorated (Mangino et al, 2020).

With respect to this issue, LORE allows a patient to manifest in writing4 her desire to receive assistance in dying should she no longer be in full possession of her faculties or lack the ability to make a free, willing, and conscious request (art. 5.2). While this formulation may offer a solution in cases of unconscious patients, it may be insufficient to resolve similar circumstances in which patients are conscious but mentally impaired.

This question is particularly intriguing considering that LORE recognized the relevance of a patient's perception of her own suffering. Specifically, the law recognizes the right for a patient to request assistance to die when the physical or psychological suffering is considered by the patient to be intolerable (art. 3.c.). This language may prove problematic when a patient, while suffering a degenerative mental disease, might not necessarily be considered to have the capacity to experience the requisite intolerable-applying literal interpretation of the law-necessary to provide a legitimate basis for the assistance to die.5 This controversy may be further complicated when Advance Care Directives ("ACD") are involved in patients with severe mental diseases. Specifically, the issue would arise as to whether an ACD should prevail with the same force over the patient's will when she is mentally disabled but arguably does not suffer the requisite intolerable pain.

In fact, this issue has been analyzed in the Guidelines for the Practice of Euthanasia (Manual de buenas prácticas en eutanasia), a document approved to detail the concrete process according to the LORE' Sixth Additional Disposition. In this sense, these Guidelines establish a procedure to evaluate the patient's capacity which requires the evaluation of two different doctors. After a clinical interview aimed at evaluating her capacity of understanding, reasoning, and deciding, the doctor in charge of the evaluation could ask for support tools to better evaluate the cognitive decline, like the Minimental State Examination (MMSE), the Aid to Capacity Evaluation (ACE) or the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Treatment (MacCAT-T). Finally, the doctor in charge must consult another one having specific formation about the patient's pathology who, in turn, will elaborate a second report concerning the fulfilment of the requirements established to provide assistance to die and evaluating the cognitive capacity of the patient. After that, the Guidelines state that:

If both [doctors] agree in the patient's incapacity, the decision concerning the request of assistance to die will be based on the content of the advance directives (or analog document), if this document states, in a clear and univocal way, the circumstances in which the patient requests assistance to die in the case of incapacity; and nothing suggests that the patient's will has changed6 (Ministerio de Sanidad, 2021: 89).

In this sense, these guidelines establish that if the patient finds herself in a state of cognitive impairment and she had explicitly asked in her ACD for assistance to die given that context, the medial staff must proceed in that sense. However, as the Guidelines require that "nothing suggests that the patient's will has changed", the manifestation of a patient with cognitive decline against receiving assistance to die could still prevent its application. Finally, if the doctors disagree with the cognitive state of the patient, the final decision will be on charge of the Warranty and Evaluation Committee ("CGE").

Even though this document provides clarity to the concrete process of evaluating the cognitive capacity of the patient and states that, given cognitive impairment, the ACD becomes the manifestation of the patient's will, the process yet lacks of an explicit solution to the two key points previously mentioned: a) how to evaluate if the patients have a severe, chronic and disabling suffering or a serious and incurable disease; b) how to proceed when the patient's current manifestations oppose to the assistance to die requested in the ACD.

On the one hand, if we apply the LORE in literal terms, as the article 5.2 recognizes that the assistance to die can omit the requirement of the patient's consent when a doctor determinates that she is not in "her sound and sober senses" and had previously establish her will in ACD, we could defend that doctors should go on with the process even against the will of the patient with cognitive impairment. On the other hand, considering the particularly need of protecting the life-and therefore the exceptional nature of the assistance to die-and making and extensive interpretation of the article 6.3, which establishes that "The requester or the assistance to die can revoke her request at any moment, (...)"7, we could defend that the patient's opinion should be listened even when mentally diminished.

In sum, because a patient's subjective considerations regarding the level of her suffering is contemplated under LORE, the formulation and implementation of coherent guidelines regarding circumstances in which an ACD and the "present-time" patient's directions might conflict are increasingly relevant. However, it is likely that any additional legislation explicitly regulating this procedure would still be insufficient to resolve this legal conundrum, as any ambiguous statement or interpretation of this norm could let to the claim that the rights of the patients are being transgressed and to the starting of criminal accusations. In this sense, most likely courts will eventually be required to establish through jurisprudence the ponderation between the fundamental rights at stake-particularly how to guarantee the best possible representation of the patient's will-and the concrete process to develop assistance to die in those contexts.

4. The Two Modalities of the Assistance to Die

LORE establishes two different modalities of "assistance to die" that are derived from the right to euthanasia recognized under the law. Pursuant to article 3.g., a patient's death permitted under LORE may result from the direct administration of a substance from a health professional (3.g.1) or from self-administration by the patient of a substance provided or prescribed by the health professional (3.g.2). In this sense, while the first mode of assistance matches the definition of euthanasia-as the patient's death is produced by the direct administration of a drug from a third party-the second mode is more properly considered to be cooperation in suicide-as the doctor merely provides the substance that the then patient voluntarily ingests to cause her own death. In this context, the patient generally can decide the degree of involvement that she wants the doctor to have concerning her death. For obvious reasons, when the patient is not in a coherent state ("Situación de incapacidad de hecho") and has manifested her will to end her life, the euthanasia should necessarily take place through direct administration.

Nonetheless, there are some inconsistencies in regulation's application with respect to assistance to die. Specifically, article 3.g.2 permits the provision or prescription of the drug to the patient so that she may self-administer it to cause her own death. However, the exact nature and extent of the patient's autonomy under these circumstances is not clear, especially concerning the possibility of receiving assistance during this process. In one sense, the concept of "self-administration" may be considered flexible enough to include not only the patient's actual voluntary ingestion of the drug under her own power but also any additional collaboration she may require with respect to that process from a third party. Alternatively, a narrower interpretation might conclude that "self-administration" includes only the direct acts of the patient and, in that sense, forbids any collaboration. With respect to this issue, Juanatey, 2011 clearly defends the more expansive interpretation and rejects the narrower one as exceedingly formalist. In this sense, according to the theory of participation under criminal law, any collaboration in harmony the doctor's command and respectful of the law should be considered legal and appropriately authorized under the law (2021: 80).

Tomás-Valiente (2021b: 104), on the other hand, explored the medical nature of the assistance to die established by LORE. In this analysis, caution should be exercised when considering the extent to which the concept of self-administration applies in this context as the term is not clearly defined under the law. The primary reason for this is that LORE was designed to function as an exception to the Criminal Code-that is, only if the behavior consistent with the language of the law does it qualify for the exception to the crime of cooperation in suicide (art. 143.5). Consequently, it may reasonably be surmised that any act of cooperation in suicide that is included in article 143 and not explicitly excluded by LORE would constitute the crime of cooperation in suicide. This reasoning is further supported when considering that this law systematically limits the right to assist to euthanasia to medical personnel (see, e.g., art. 1, 3.g and 11). In this sense, the ambiguity in the law becomes problematic as it means not only that the cooperation in causing the death of the patient is permitted, but it also reconfigures the nature of the subject providing legitimate assistance to die. In other words, despite LORE's explicit limitation of the permissibility of these acts to medical staff, the statutory ambiguity perhaps indicates the acts of any person collaborating with the patient who successfully fulfils the requirements established by the law and that aims at self-administrating the drug should be permitted to do so.

5. Role of Medical Staff During the Euthanasia Process

One of the key aspects of the Spanish regulation of euthanasia is the medical nature of its legislation. Specifically, medical staff is afforded a key role during various moments of the procedure: as a witness to the patient's will of putting end to her life, as an informative expert regarding palliative and alternative treatments, as an evaluator of the patient's health and as the direct dispenser of the drugs. In addition, doctors are subject to certain administrative obligations concerning the patient's clinical history in order to guarantee that the mandated procedures occurred, including notification after euthanasia takes place.

Even so, the role of medical staff substantially differs depending on the type of "assistance to die" that a patient requests. If the patient chooses to receive the drug directly from the principal doctor on her case, "she and the medical staff will have to assist the patient until the moment of her death" (art. 11.2) 8, thus implying the accompaniment until the patient's death. Alternatively, if a patient chooses the euthanasia regulated by article 3.g., a doctor should limit her actions to prescribing and providing the necessary drug and "keep the due task of observation and support until the moment of her death" (art. 11.3).9

The second type of euthanasia described above generates a question as to the extent of the medical staff´s "observation and support" duty. Interpreted narrowly in strict accordance with its literal terms, this article requires ongoing observation and assistance from the moment the doctor prescribes the drug until the moment the patient dies. This interpretation presents two interesting analytical issues. The first issue is the delimitation of the role of the medical staff in the article 3.g. type of euthanasia; specifically, to what degree are the doctor and medical staff required to observe and assist the patient? This question is particularly relevant at the time of determining medical misconduct and associated potential legal liabilities. The second issue concerns the extent of the discretion afforded to the patient in self-administering the drug. Specifically, if the medical staff must observe and assist the process of self-administration, how much autonomy does the patient have to decide where, when and how to ingest the drug?

This question in fact leads to a related issue concerning the specific locations where euthanasia is permitted to take place. As previously indicated, LORE provides that the provision of assistance to die may occur in public, private or concertados (semi-public) health centers, as well as in the patient's residence (art. 14). However, the law does not provide an explicit explanation of the implications of this process and how it might be implemented. More concretely, LORE does not clarify the manner in which a patient's right to choose the place of assistance to die should occur when she chooses self-administrated euthanasia. A literal interpretation could support the notion that the law restricts the spaces where self-administrated euthanasia may occur. Specifically, a patient may choose between consuming the drug at the applicable medical facility or in her home, but not in any other place. Such an interpretation would significantly diminish the patient's autonomy, with respect to the location where euthanasia may take place. In fact, this interpretation is coherent with the Guidelines for the Practice of Euthanasia, as they establish that the administration of the euthanasia will only take place at the hospital or at the patient's home (Ministerio de Sanidad, 2021: 22)10.

It is important to note as well that this provision must be read along with article 11.3, which mandates that the medical staff observe the patient following her self-administration of the drug. In that way, it is reasonable to inquire whether the medical staff's duty "of observation and support until the moment of her death" (art.11.3) implies verification that the euthanasia is administered in the manner required by the law. In fact, the Guidelines establish that "During the realization of the assistance to die, the medical staff will be present during the whole process" (Ministerio de Sanidad, 2021: 29)11. In addition, it also mandates the medical staff to be prepared to administrate intravenously additional doses of the drug when the oral ingestion fails at provoking death or causes unnecessary pain.

This question is particularly important considering that the law does not mandate any maximum period between the acceptance of the assistance to die and the prescription and consumption of the drug. In fact, pursuant to article 18.b, the CGE has two months after a positive report to verify that the assistance to die was effectively administered. After that, according to the Guidelines of the LORE, it will be presumed that the patient desisted from her desire of being assisted to die (Ministerio de Sanidad, 2021: 23).

Nonetheless, this provision is unclear because LORE does not mandate consequences that attend failure to provide appropriate assistance to death within the delimited term. It is unclear, for example, whether the process should be restarted from the beginning or, in the case where the assisted death occurs after the mandated term, whether such assistance could potentially generate criminal responsibility.

In sum, it is reasonable to conclude that the medical staff's duty of observation and assistance may imply stronger involvement as more time passes from the date of prescription. Increased involvement would allow for medical evaluation to observe, among other things, whether the patient has maintained the necessary will or has come under external pressure. In this sense, because LORE requires a thorough process to guarantee that a patient's will to put an end to her life remains consistent and is not subject to external pressure, it would seem reasonable to conclude that the task of observation and assistance required of the medical staff would include verification that the process was executed appropriately-i.e., that the patient has not changed her will and that she is not suffering pressure to ingest the drug from any family member or other third party.

In addition, although LORE mandates the medical staff perform a correct "observation and support until the moment of her death", it lacks the legal resources to develop this protection. In this sense, the law strictly focuses on resolving whether or not the patient has the right to receive the assistance to die: it requires, for example, the informed request of the patient to be manifested twice during a twenty day period, a report of the doctor evidencing that the patient has fulfilled the law's requirements and a final revision of the CGE report.

Nonetheless, after the final permission of the CGE is granted, there is no further statutory language to establish a coherent procedure to revise the plan if necessary under the authority of the medical staff observing and supporting the process until the patient's death. In fact, according to the LORE's Guidelines, the place and the moment of the assistance to die will be discussed between patient and doctor under the principle of "flexibility". This implies that the date can be determined and even delayed in time according to the patient's needs-even though always between the two-months period. In this sense, LORE contains a contradiction: it places responsibility on the medical staff without establishing any legal mechanisms to prevent a violation of the procedure.

However, unlike the previous problematic concerning the assistance to die in patients mentally impaired, this ambiguity could be resolved with minor legislative changes. Firstly, because the main conundrum involves the lack of concrete processes to guarantee how the medical staff must behave during the process of patient' self-administration or the direct application of the drug causing death. And secondly because the main need here is to develop a protocol to corroborate the patient's will to continue with the assistance to die-without questioning her mental capacity or an eventual application of the ACD. Therefore, the modification of the Guidelines for the Practice of Euthanasia, in the sense of including more detailed directives about the timing and the concrete responsibilities of the medical staff, could be sufficient to provide more legal certainty to all the parts involved.

6. Conclusion

On March 24, 2021, Spain joined the small group of countries that have legalized euthanasia and recognized a patient's right to put an end to her life while receiving expert medical assistance. In this sense, LORE established a complex process aimed at guaranteeing that the patient's will is informed, sustained over a period of time and free of any external pressure. Under its mandated procedure, the law recognizes a significant role to be played by the medical staff. Doctors must, for example, among other things, evaluate the patient's physical and phycological state, inform the patient about possible treatments and assist the patient in the administration, provision or prescription of the medication that provokes her death.

In this connection, the Spanish government produced a model for assistance aimed at maximizing ability to control the disposition of her life while simultaneously imposing limitations concerning the state of the patient's health her consent to the procedure. Nonetheless, despite LORE's drafters' efforts to establish a consistent and coherent procedure, certain provisions of the law (especially art. 3, art. 11 and art. 14) do not provide express regulation regarding certain controversial issues relating to the implementation of euthanasia. First, LORE does not expressly regulate the assistance to die concerning patients with mental illnesses, thus leaving uncertain how to evaluate a patient's mental state and, moreover, when such illnesses may constitute such cognitive impairment to affect the legitimacy of the entire process. Second, while the law allows a patient to self-administer the substance causing her death, it does not recognize the possibility of obtaining assistance from non-medically trained third parties. In this sense, because the law constitutes an exception to the application of the crime of cooperation in suicide, a non-medical provider's cooperation with a patient's self-administration of euthanasia might not be legally protected and, as such, may eventually lead to legal liability or prosecution. Third, there are inconsistencies concerning the role of medical staff during the process of providing assistance to die, particularly with respect to patients who decide to self-administrate the relevant drug. Specifically, the law provides no clear explication of the extent of the medical staff's duty of "observation and support" after the provision or prescription of the drug.

In sum, even though LORE clearly establishes a cornerstone in the regulation of a patient's right to receive assistance to die, and has proposed an adequate system to guarantee the protection of all parties' rights, it exhibits certain inconsistencies that diminishes its clarity and may jeopardize the rights of both patients and medical staff. In this sense, this paper was intended to assess and provide some insight with respect to these ambiguities in order to provoke discussion that permits more efficient implementation of this new law.