Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista Española de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial

versão On-line ISSN 2173-9161versão impressa ISSN 1130-0558

Rev Esp Cirug Oral y Maxilofac vol.27 no.6 Madrid Nov./Dez. 2005

Artículo clínico

Lateral orbitotomy using a temporal approach

Orbitotomía lateral mediante abordaje temporal

H. Herencia Nieto5, J.J. Verdaguer Martín1, F. Riba García2,

J. Calvo de Mora Álvarez5, A. del Amo Fernández de Velasco5,

R. Pujol Romanya3, C. Navarro Cuéllar4

|

Abstract: The lateral orbitotomy it still the surgical technique of choice for biopsies or the removal of intraorbital lesions that are lateral to the optic nerve, for biopsies of the optic nerve itself and for removing the lacrimal gland. Key words: Orbit; Tumor of the orbit; Orbital surgery; Lateral orbitotomy.

|

Resumen: La orbitotomía lateral sigue siendo en el momento actual la

técnica quirúrgica de elección para la biopsia o extirpación de lesiones

intraorbitarias laterales al nervio óptico, la biopsia del propio nervio

óptico y la extirpación de la glándula lacrimal. Palabras clave: Órbita; Tumor de órbita; Cirugía de órbita; Orbitotomía lateral. |

Recibido: 5.07.05

Aceptado: 15.11.05

1 Médico Adjunto. Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial. Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid.

2 Médico Adjunto. Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial. Complejo Hospitalario de Ciudad Real.

3 Médico Adjunto. Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial. Hospital Virgen de la Salud, Toledo.

4 Médico Adjunto. Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial. Hospital Universitario de Guadalajara.

5 Médico Residente. Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial. Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, España.

Correspondencia:

Honorio Herencia Nieto.

Calle Jose Domingo Rus, nº23 1º1 escalera derecha. 28043. Madrid, España.

e-mail: jonor@excite.com

Introduction

The orbit and its contents represent an entity that is anatomically complex. The existence of certain pathologies at this level makes surgical treatment compulsory (biopsies or removal of tumors, surgical decompression of Graves-Basedow disease etc.). Choosing the most appropriate approach in view of the type of pathology and its location within the orbit, is fundamental for ensuring the success of the procedure.1,2 To date, the lateral orbitotomy is considered the ideal technique for reaching lesions in the lateral half of the orbit, for biopsies of the optic nerve and for the removal of lacrimal glands.1,3,4

Traditionally the lateral wall of the orbit was reached with a skin incision into the external canthal area or into the upper eyelid crease. Since the procedure was first description by Krönlein in 1888 and up until the present time, the incisions have undergone many modifications (Fig. 1).

Krönleins original incision is along a convex curve anterior to the lateral orbital rim area. In 1960, Stallard and Wright popularized their italic «s» shape incision that ran parallel to the external orbital rim from the end of the brow, finally running parallel to the zygomatic arch. This approach route has been widely used by most surgeons up until the appearance of the eyelid incision. This is a modification of the Stallard-Wright incision, as it runs along the upper eyelid crease. It has now displaced its predecessor and it is currently considered by many authors as the incision of choice for the lateral orbitotomy.5

Although the results obtained with this incision can be considered satisfactory in most cases, it is not exempt of potential complications such as visible scars, lesions of the elevator eyelid muscle and eyelid retraction.6

In order to avoid these complications, different approaches have recently been proposed in craniofacial surgery for carrying out the lateral orbitotomy.7 The most important are the coronal7,8 and temporozigomatic approaches,9 and the approach used for the postero-lateral orbitotomy which entails a skin incision at the temple. 6,10,11 In this case of ours, this last approach was considered the route of choice for carrying out the intervention, as the complications that arise with the classical incisions could be avoided. Also, it allows proper exposure of the surgical field, enabling the surgery to be carried out.

Material and method

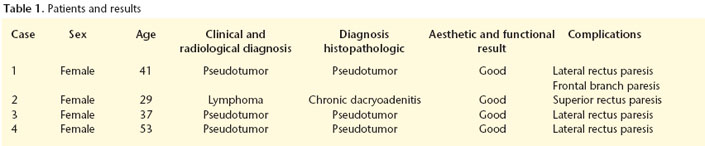

Over the last three years four patients underwent surgical procedures (all female) and lateral orbitotomies were carried out by means of an incision into the temple area (Table 1).

All four patients had initially displayed similar clinical symptoms such as exophthalmos and diplopia with an onset that was both progressive and rapid, and which had no associated symptoms. They were first evaluated by the Ophthalmology Department. In all cases imaging studies were carried out (MRI and/or CAT) as part of the diagnostic study. In three of the cases the suspected radiological diagnosis was of orbital pseudotumor. In the fourth case, an extraconal tumor-like mass could be appreciated that was affecting the supero-external part of the orbit. It was consistent radiologically with a lymphoma.

The three cases with a diagnosis of pseudotumor were treated with systemic corticoids according to the Ophthalmology Department protocol. As the response proved inadequate, they were referred to our department for biopsy. The case that was compatible with lymphoma was referred to us for diagnostic confirmation by biopsy without previous treatment.

In all four cases the size and location of the mass made using the lateral orbitotomy advisable as a biopsy technique.

Surgical technique

The incision used for carrying out the lateral orbitotomy in this particular case is very similar to that used for harvesting the temporalis flap.

The head is shaved in the temple and sideburn area and the skin in this area is infiltrated with an anesthesia-vasoconstrictor mixture (in our case lidocaine with adrenalin at a concentration of 1:100.000) these are steps previous to the surgery that, although not essential, facilitate the latter considerably.

A curvilinear incision is made with a superior convex curve, two centimeters above the superior temporal line, and with a vertical extension in the preauricular region to the tail of the helix (Fig. 2). This vertical extension can be continued downwards if necessary, for greater exposure of the surgical field. Most of the incision line is designed so that it is behind the hair line, which means that it is hidden. Extending the anterior part of the incision line very far is not necessary as scarring in the frontal region should be avoided and care should be taken not to damage the frontal branch of the facial nerve that runs a centimeter and half behind the orbital rim.12

The posterior part of the incision is deepened to the deep layer of the temporal fascia. From this point the dissection continues forwards over the fascia, so that the frontal branch of the facial nerve that is within the subcutaneous cellular tissue and the temporoparietal fascia is not damaged.13,12 The lateral and superior orbital rims are then accessed (Fig. 3). From this point the technique is the same as that used in any lateral orbitotomy regardless of the skin incision used.

The periosteum is cut approximately two millimeters behind the lateral orbital rim. The temporalis muscle is retracted posteriorly, it is disinserted from the temporal fossa, and the external part of the lateral wall of the orbit is exposed. The periosteum in the internal part of the orbit should also be stripped carefully.

Before carrying out the osteotomies, repositioning the bone fragment that is to be removed for accessing the intraorbital contents, should be planned. For this the bone incisions that are to be made are marked with a sterile graphite pencil, and the lowprofile titanium miniplate is first shaped and the holes for the screws are made in the lateral orbital wall, taking care that at least two screws are left at each side of the marks made.

Next, the contents of the orbit are protected by gently placing a malleable valve on the inside of the orbit, between the bone and the periosteum. The upper incision is carried out on a level with the frontozygomatic suture or above it. The lower one is made where the zygomatic arch and the lateral orbital rim join. The osteotomies are carried out with an oscillating saw and in the direction of a point approximately a centimeter and a half behind the orbital rim, over the greater wing of the sphenoid bone. The posterior vertex of the bone fragment that has been removed will therefore have a triangular shape (Fig. 4).

If necessary, the osteotomies can be completed with a fine chisel. Examining the inside of the orbit helps to control properly where the cuts into the bone are made, which is especially important when trying to avoid entering the anterior cranial fossa on performing the upper cut.

After removing the bone fragment, the periorbita is incised and the intraorbital content is reached by means of dissecting the periocular fat and moving the lateral rectus muscle away from the eye if necessary.

After the intraorbital procedure, the bony wall is replaced using the low-profile miniplate and the incision is closed by layers (periosteum, temporo-parietal fascia, subcutaneous layer and skin). For the first 24-28 hours leaving a subcutaneous drain is advisable so that postsurgical hematomas are avoided.

Case Report

Patient, 29 years old, was evaluated by the Ophthalmology Department due to axial proptosis of the left eye and diplopia that had only recently appeared (one month approximately) and that was progressing rapidly. MRI was carried out which showed the existence of an extraconal mass in the supero-external region of the left orbit which appeared radiologically to be a lymphoma (Fig. 5).

Given the characteristics and location of the mass, a lateral orbitotomy was considered as the best route for the biopsy- excision. The technique was carried out by means of an incision into the temple, and during the surgical procedure a well-defined, encapsulated mass was found that could be completely removed. The anatomopathologic diagnosis of the specimen was of chronic dacryoadenitis.

The aesthetic and functional results were excellent, with the only complication being paresthesia of the upper and lateral rectus muscles of the left eye, that disappeared spontaneously after two months. Six months after the surgery, no complications of any type have arisen.

Results

In all four cases the temporal approach proved adequate for carrying out the lateral orbitotomies and for accessing the intraorbital lesions. In three cases the masses that were found were not well-defined and a biopsy was performed. In the case that was diagnosed radiologically as a lymphoma, a well-defined encapsulated mass was found that could be removed completely. The anatomopathologic analysis confirmed the diagnosis of orbital pseudotumor in the three cases with this suspicion. In the cases of possible lymphoma, the definitive diagnosis was of chronic dacryoadenitis and the mass removed was actually from the lacrimal gland that had been affected by inflammatory phenomena.

The patients with the definitive diagnosis of pseudotumor of the orbit were sent back to the Ophthalmology Department to continue treatment (systemic corticotherapy at a higher dosage than had been given previously).

The aesthetic result was excellent in all cases. The surgical scar was completely covered by hair and there were no visible sequelae of any type. Obviously, this approach avoids any incidence of eyelid retraction given the access route chosen (Fig. 6).

In all cases transitory paresthesia was produced of the lateral and upper rectus muscles of the eye (as a result of intraocular manipulation, not the access route itself).

The only complication that could be directly attributed to this approach was the appearance in one of the patients of transitory paresthesia in the frontal branch of the facial nerve.

To date there have not been any permanent or long term complications in any of the patients.

Discussion

Surgery of the orbit tends to carry a high degree of difficulty due to the existence of a large numbers of important structures in a physically small space and with complex anatomic relationships. Perhaps it is because of this complexity that there is no single technique that is «ideal» for reaching the orbit, and different procedures are needed according to the type of pathology and the size, number and location of the lesions.

Although new ways of reaching the interior of the orbit are continually appearing (with endoscopy standing out as it is increasingly used),14 the lateral orbitotomy is still the technique of choice according to most authors for excision (and currently for biopsies) of lesions that are lateral to the optic nerve (intraconal as well as extraconal) and of the lacrimal gland. This surgery requires accessing the lateral wall of the orbit and removing a fragment by means of an osteotomy so that the contents of the orbit can be reached.

The procedure has undergone many modifications since it was first described by Krönlein, so that the potential aesthetic and functional sequelae can be reduced for the patient.15 These modifications consist generally in changes in the skin incisions for accessing the lateral wall of the orbit, as scars that are more «aesthetic» are sought. The way osteotomies are carried out has, on the other hand, been kept practically the same with regard to the original description, although some authors have introduced variations, so that closure and replacing the bone fragment removed when gaining access to the interior of the orbit is made eariser.16

The ideal incision for approaching the lateral wall of the orbit should avoid any complications and sequelae for the patient as much as possible, and the access to the surgical field should be wide enough to allow the area to be reached with ease. Over the last years the incision most used for carrying out a lateral orbitotomy has been the upper eyelid approach. Although the results obtained are generally acceptable, and adequate access to the lateral wall of the orbit is facilitated, it is not exempt of potential complications, as the orbicular muscle has to be sectioned at least minimally together with the lymphatic vessels of the eye lid. As a result of this, eyelid retraction can appear secondary to surgery together with lesions of the lid elevator muscle. Lid opening may be difficult and there may be permanent eyelid edema. In addition to this, despite being camouflaged in the eyelid crease, it cannot be claimed that the scar is completely invisible.

Other approaches have appeared, some in conjunction with craniofacial surgery, that try to avoid these inconveniences by using alternative incisions. One of the most versatile is the temple incision. In addition to providing excellent surgical field exposure and facilitating to a large extent the intervention, it has two great advantages: the scar is nearly completely hidden by hair and the eyelid does not have to be touched. The sequelae that may remain in this area from using other approach routes are in this way avoided. The surgical plane between the deep temporal and temporoparietal fasciae is practically avascular, which means that the surgical technique is, in most cases, relatively simple.

The chief inconvenience that can be attributed to this approach is the possibility of damaging the frontal branch of the facial nerve. If the surgical layers are respected, and if care is taken when carrying out the dissection, this complication is very infrequent. On the other hand, this can be due to traction phenomena and compression on the nerve on separating or carrying out the dissection, and not to the nerve being damaged directly. When this appears it tends to be partial (paresis and not paralysis), and in most cases there is normally complete and spontaneous recovery.

Conclusions

The technique we have described here is possibly one of the most adequate for carrying out a lateral orbitotomy. The temple incision very often surpasses the classical incisions, and excellent aesthetic and functional results are obtained. There is minimum morbidity for the patient and, in most cases, it is technically simple. For these reasons, it can be perfectly recommended as an alternative to other incisions, including the upper eyelid incision, that has been chosen by most authors over recent years.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Alejandra Rojas for her generous contribution in carrying out this work.

References

1. Nerad JA. Cirugía oculoplástica: los requisitos. En: Pellerin P, Lesoin F, Dhellemmes P, Donazzan M, Jomin M. Cap. 14. Elsevier Science 2002;387-417. [ Links ]

2. Schick U, Dott U, Hassler W. Surgical treatment of orbital cavernomas. Surg Neurol 2003;60:234-44. [ Links ]

3. Arai H, Sato K, Katsuta T, Rhoton AL Jr. Lateral approach to intraorbital lesions: Anatomic and surgical consideration (surgical anatomy and technique). Neurosurg 1996;39:1157-63. [ Links ]

4. Rothon A L Jr. The orbit. Neurosurgery 2002;51(Suppl 1):303-34. [ Links ]

5. Abouchadi A, Capon-Degardin N, Martinot-Duquennoy V, Pellerin P. Orbitotomie latérale par voie palpébrale supérieure. Annales de chirurgie plastique esthétique 2005;50:221-7. [ Links ]

6. Carta F, Siccardi D, Cossu M, Viola C, Maiello M. Removal of tumours of the orbital apex via a postero-lateral orbitotomy. J Neurosurg Sciences 1998;42: 185-8. [ Links ]

7. Kalmann R, Mourits M Ph, van der Pol JP, Koornneef L. Coronal approach for rehabilitative orbital decompression in Graves´ ophthalmopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 1997;81:41-5. [ Links ]

8. Tessier P. Inferior orbitotomy. A new approach to the orbital floor. Clin Plast Surg 1982;9:569-75. [ Links ]

9. Pellerin P, Lesoin F, Dhellemmes P, Donazzan M, Jomin M. Usefulness of the orbitofrontomalar approach associated with bone reconstruction for frontotemporosphenoid meningiomas. Neurosurgery 1984;15:715-8. [ Links ]

10. Cossu M, Pau A, Viale GL. Postero-lateral microsurgical approach to orbital tumors. Minim Invas Neurosurg 1995;38:129-31. [ Links ]

11. Viale GL, Pau A. A plea for postero-lateral orbitotomy for microsurgical removal of tumours of the orbital apex. Acta Neurochir 1998;90:124-6. [ Links ]

12. Urken ML. Atlas of Regional and Free Flaps of Head and Neck Reconstruction. New York 1995, Raven Press. Cap. 14, pp. 197-211. [ Links ]

13. Rouvière H, Delmas A. Anatomía Humana. París 1994, Masson. Tomo I, pp. 525 y sig. [ Links ]

14. Tsirbas A, Kazim M, Close L. Endoscopic approach to orbital apex lesions. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2005;21:271-5. [ Links ]

15. Harris GJ, Logani SC. Eyelid crease incision for lateral orbitotomy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 1999;15:9-16. [ Links ]

16. Hunter KLY, Chong YH, Chan SK, Tse KK, Chan N, Lam DSC. Modified lateral orbitotomy for intact removal of orbital Dumbbell dermoid cyst. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2004;20:327-9. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em