INTRODUCTION

In recent years, a number of behavioral studies have tried to explain the relationship between nutrition and depressive disorders, taking into consideration overeating, frequency of eating, and preferences for certain foods 1,2,3. Depression is frequently accompanied by appetite changes, which may take the form of either decreased appetite (melancholic depression) or increased appetite (depression with atypical features) 3,4.

According to affective theories, people with depression may use food not only for nourisment, but also to cope with negative emotions; therefore, food intake can be considered as an inadequate coping mechanism in response to stress and tension that can be part of the causal link for developing overweight or obesity 5,6. Other theoretical frameworks have focused on neurobiological data such as brain-environment interaction referred to as midbrain dopamine system 3. Food represents a potent natural reward and gratification related to dopamine production that influences nutrition choice regarding higher fat and sugary foods ("comfort foods") 7. As part of a broader framework, reduced affective self-control (impulsive food choices), particularly for "comfort foods", and a desire to achieve immediate reward may be a shared cognitive mechanism contributing to the high prevalence of co-morbid mood disorders and weight gain 8. Additionally, increasingly greater food availability over recent decades may be another factor that contributes to the relationship between nutrition and depressive symptoms 3.

Studies on food cravings have mostly focused on carbohydrates consumption and, especially, mildly dysphoric mood. It is commonly assumed that carbohydrate craving is related to serotonin deficit 9; therefore, some people tend to overeat sugary food (carbohydrate beverages, pastries, sweets and chocolate, cakes and biscuits) to improve negative mood states 10,11.

Consistent with this theory, recent data suggests that there is an association between a preference for sweet taste and a higher depression score in patients with severe obesity 12. Other studies have shown that intake of "comfort foods", sweet foods, and a Western-type diet had an effect on physiological and psychological wellbeing and was associated with a higher depression score and obesity in the general population, especially in women 13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21.

Regarding college students and their eating habits, in studies performed in Germany 22, the USA 23 and the United Arab Emirates 24, it has been reported that young adults tend to overeat and consume unhealthy food in response to stressful situations. In the USA, Moorevile et al. 2 have shown that in non-treatment-seeking youths, aged 8-17 years, depressive symptoms were associated with significantly greater consumption of total energy and energy from sweet snack foods, which could lead to weight gain over time.

However, there are contradictory findings with respect to negative mood and food intake. In spite of the fact that in scientific literature food choice was considered as a deliberate strategy to modify temperament and mood, some researchers have found no consistent differences in dietary composition in comparing the periods of high and low life stress or depression. In addition, to this day it remains unclear whether the food consumption improves negative moods or whether the intake of certain foods can have an effect on human behavior 25.

In the study by Mikolajczyk et al. 26, conducted in three countries (Germany, Poland and Bulgaria) among first-year college students, a positive association has been found between food consumption (i.e., fast-food, cakes, snacks, sweets) and stress, but not between food consumption and depressive symptoms among female students; however, these patterns were not found among male students.

Additionally, Fulkerson and Nancy 27, in the study on depressive symptoms and eating behavior in adolescents, have shown that total caloric intake and snaking frequency were not significantly associated with depressed mood.

In Latin America, depression represents a growing problem among young adults. A high prevalence of depressive symptomatology has been reported among college students, from 11.8% to 30%, which can rise to 50% during stressful situations 28,29. Additionally, in Mexico overweight and obesity have a high and increasing prevalence, 36.3% in adolescents from 12 to 19 years old and 72.5% in individuals over 20 years old 30. Therefore, it is important to study eating habits and their relationship to mood disorders in young population groups. When students experience the transition to university life they are frequently exposed to stress, fatigue, and time restraints. Poor eating habits acquired at this age generally continue into adulthood and may lead to weight gain. An understanding of the influence of negative emotions on eating behavior, along with nutritional education, may be essential in preventing overweight/obesity in adulthood.

The aim of the present study was to investigate a possible association between perceived depression and unhealthy food consumption in college students in Mexico City, and to test the hypothesis that college students with a higher level of depression would have higher consumption of carbohydrate-rich and/or energy-rich food. Therefore, the objectives of this study were: a) to determine the prevalence of depression and unhealthy food consumption in first-year students, both men and women; and b) to analyze the possible association between depression score and unhealthy food consumption.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

SAMPLE

A cross-sectional study was performed at the Autonomous Metropolitan University in Mexico City with first-year students (n = 1,131), who participated in an on-line survey from a total population of 1,364 freshman students enrolled at the university in the autumn of 2016. The response rate was 82.9%.

The questionnaire section of this study was part of the online health survey for freshman students applied during the first week of classes in computer rooms.

ETHICS

The questionnaire was completed anonymously, and the participants were assured of data confidentiality. The students participated on a voluntary basis, and they acknowledged informed consent on-line. The University Review Board approved the project, where ethical aspects were considered.

INSTRUMENTS

A Spanish-language version of the 20-item depression scale created by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies (CES-D) was used to identify depressive symptoms.

This instrument has been validated and utilized in various studies with non-clinical Mexican populations 31. Twenty Likert-type items assessed the frequency of depressive symptomatology in the previous week, including depressed mood, feelings of guilt and worthlessness, psychomotor retardation, and sleep difficulties. This scale had shown a good internal consistency in Mexico's student population, with Cronbach's alpha 0.87. The maximum score of the instrument is 60, indicating severe depression, and the minimum score is 0, indicating absence of depressive symptoms. In this study, a cut-off point of 16 was used to recognize the presence of depressive symptomatology.

The assessment of food intake was performed using the Food Frequency Questionnaire, which consists of 69 items and encompasses all groups of foods 32. The carbohydrate-rich and/or energy-rich foods (unhealthy foods) were selected from this list and categorized into five groups: cereals (white bread was selected from white wheat cereals), fried food (such as potato chips, corn chips and tortilla chips, French fries, greaves and fried bananas), sweet food (cakes, cookies, pastries, sweets, chocolate, cakes, biscuits, sweet bread), and sweetened beverages (sugary soft drinks, natural and industial jucies). The fast food group (such as hamburgers, fried chicken, pizza, or sausages) was added to the questionnaire. Food intake frequency was measured as the consumption of respective food choices over a number of days of the week with the corresponding answers: almost never, once a week, two or three times per week, four or more times per week. A frequency of consumption of 2-3 times or more per week was considered as unhealthy behavior 33. Physical activity was assessed with the question "How many times per week do you exercise for at least one hour?" Less than 75 minutes of vigorous physical activity per week was considered as unhealthy behavior in line with the World Health Organization criteria and the recommendations of the American College Health Association 34,35.

Self-reported weight and height were recorded and BMI was calculated. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria 36, the cutoff point for being overweight was BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2; for being obese, ≥ 30 kg/m2; and for being underweight, < 18.5 kg/m2.

DATA ANALYSIS

The main characteristics of the study group are presented as means and standard deviations for continuous variables and percentage for categorical variables. To study the associations between food consumption frequency and depression, 78 students with low BMI (BMI < 18.5) were excluded from this analysis. A logistic regression analysis was carried out for food consumption frequency and CES-D depression score was divided by quartiles. The observations in the 1st quartile (non or few depression symptoms) were used as the reference group. The models were constructed by sex and adjusted for age and BMI. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were obtained. Statistical significance was set at p-value < 0.05. The statistical package STATA V12 (College Station TX. StataCorp LLC) was used for data analysis.

RESULTS

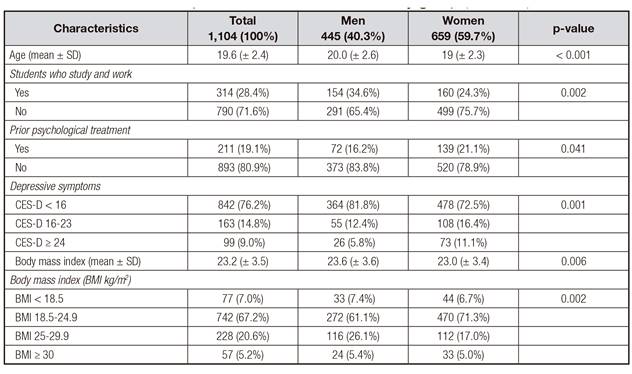

A total of 1,104 students were evaluated; 445 (40.3%) of them were men and 659 (59.7%) were women. The mean age of participants was 19.6 ± 2.4. Descriptive characteristics of the participants are presented in Table I.

About 19% of the students revealed that they had prior psychological treatment (16.2% men and 21.1% women, p = 0.041). Additionally, 268 students (23.8%) presented depressive symptoms (cutoff point of 16), more women (27.5%) than men (18.2%), p < 0.001.

Considering BMI, 228 participants (20.6%) were overweight and 57 (5.2%) were obese. Mean BMI was higher in men than in women (23.6 ± 3.6 and 23.0 ± 3.4, p = 0.006). Students with higher depression score demonstrated a higher BMI (β = 0.04, p = 0.002).

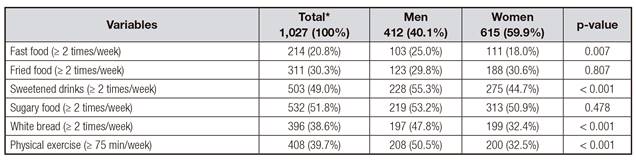

In terms of eating habits, college students frequently do not make healthy food choices and their diet was high in fried food (in 30.3% of the participants), soft drinks (in 49.0% of the participants) and, especially, sugary food (in 51.8%); less than a half of the students (39.7%) practice vigorous physical activity. Men consumed more fast food (p = 0.007), sweetened soft drinks (p < 0.001) and white bread (p < 0.001) than women; however, women exercised less than men (p < 0.001). Frequency of unhealthy eating habits and physical exercise is shown in Table II.

Table II. Eating habits and physical exercice in Mexican college students

*Students with BMI < 18.5 were excluded from this table

Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression models to analyze the relationship of depressive symptoms with food consumption and physical exercise are shown in Table III.

In women, according to bivariate analysis, the frequent consumption of fast food (OR = 2.07, 95% CI 1.13-3.78, p = 0.018), fried food (OR = 1.85, 95% CI 1.13-3.03, p = 0.014) and sugary food (OR = 2.17, 95% CI 1.37-3.42, p < 0.001), as well as exercising less than 75 min/week (OR = 1.80, 95% CI 1.11-2.91, p = 0.016) were associated with higher depression score. No association was observed between depression score and food variables in men. However, an association was found between the 4th quartile of depression score and low physical activity compared with the 1st quartile of depression score in men (OR = 2.22, 95% CI 1.26-3.91, p = 0.006).

Table III. Odd ratios from the logistic regression models for food consumption variables and depression score in female college students (n = 615)

Reference depression score 1st quartile. *OR adjusted for age and BMI.

In women, according to the multivariate logistic analysis, significant associations were observed between the 4th quartile of depression score and the frequent consumption of fast food (OR = 2.08, 95% CI 1.14 -3.82, p = 0.018), fried food (OR = 1.92, 95% CI 1.17-3.15, p = 0.010), sugary food (OR = 2.16, 95% CI 1.37-3.43, p < 0.001) and low frequency of exercise (OR = 1.80, 95% CI 1.11-2.91, p = 0.017) (Table III).

DISCUSSION

The present study examined the association of depression symptoms with unhealthy food consumption and exercise in first-year college students. Our findings support the hypothesis that higher depression score is related to unhealthy behavior (poor eating habits and low exercise frequency). According to the results, the prevalence of depression was high among participants, especially in women (27.5%), similar to other studies performed in student populations that have shown an onset of depression from a young age, its elevated prevalence among young adults, and a higher prevalence in females than in males 28,29.

A considerable number of the participants reported the consumption of unhealthy food more than two times per week, i.e., fast food (20.8%), fried food (30.3%), sugary drinks (49.0%), sweet foods (51.8%) and white bread (38.6%). Approximately one third of women (32.5%) and half of men (50.5%) performed rigorous physical activity at least 75 minutes per week. These data are consistent with previous findings that have shown low levels of physical activity and unhealthy habits such as the frequent consumption of sugary foods and a high intake of fast food in Mexican student groups 37,38. Regarding differences by sex, we found that some unhealthy eating (sweetened beverages and white bread) was significantly more frequent in men than in women, whereas women had less frequency of exercise than men had.

In women in the present study, depression symptoms were significantly associated with consumption of fast food, fried food, and sweet foods, as well as with lower exercise frequency. It is important to note that these unhealthy behaviors acquired at a young age can consequently lead to weight gain. In a systematic review and meta-analysis, it has been reported that considerable weight and adiposity gains occur throughout college life, with a mean change in weight of 1.55 kg and 1.17% in body fat mainly due to decreased physical activity and food consumption away from home 39. Obesity, unhealthy dietary practices, and physical inactivity are risk factors for the development of metabolic syndrome from early adulthood 40. In the follow-up study, performed in the USA among young adults, it has been reported that the risk of metabolic syndrome increases on average 23% per 4.5 kg of weight gained, whereas regular physical activity over time versus low activity was considered to be a protective factor 41.

Our data were similar to the results of previous studies performed in the USA, UK, Australia, and China that have shown an association between a higher depression score and intake of a Western-type diet such as processed food, fried foods, refined grains, and sugary products in the general population 13,14,15,16, as well as with obesity 17, particularly in women 18,19,20,21. According to Dubé et al. 13, intake of "comfort foods" was associated with physiological and psychological wellbeing in women: high-calorie foods (high sugar and fat content) were more efficient in alleviating negative affects whereas low-calorie foods were more efficient in increasing positive emotions. In the study by Kampov-Polevoy et al. 14, it has been shown that hedonic response to sweet taste is associated with elevated sensitivity to mood altering effects and impaired control of eating sweet foods. Consistent with our data, Jeffery et al. 15 have found that in middle-aged U.S. women, depressive symptoms were positively associated with the consumption of sweet foods and negatively associated with the consumption of non-sweet foods.

In the present study, a significant association was found between depressive symptoms and BMI. This finding corroborates the hypothesis that people with higher depression score frequently use "comfort foods" to make them feel better. It is worth mentioning that a growing number of studies have shown a reciprocal relationship between depression and higher BMI 42; therefore, it is important to take into consideration the influence of negative mood on eating behavior in overweight prevention and treatment strategies. "Comfort foods" have become increasingly available in an "obesogenic" environment over the last half-century, and individuals with depression symptoms can seek out "comfort food" in order to improve their psychological wellbeing 3. A rational coping style (i.e., planning to solve a problem or thinking of an alternative way to solve it), is generally more effective than an emotional eating style, and these skills must be learned from an early age. The transition to university life is a stressful experience for many students; therefore, time management, stress and problem coping skills should be taught for those susceptible to depression.

However, we did not find any association between sweetened drink consumption and depression score, nor has an association between unhealthy eating behavior and depression score been found in men. The above suggests that these eating behaviors are more typical for women, and men may have other ways of managing their negative emotions and stressful situations 13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21.

Additionally, non-consistent results reported in this domain may be explained by the fact that depressive symptoms or emotional stress can lead to either increased or decreased appetite. Effects of emotions on eating have been studied extensively. Surveys have shown that most people experience changes of appetite and eating behaviors in response to emotional stress: 11% to 55% eat more, while 32% to 70% eat less 43. Therefore, due to individual variability it remains difficult to predict how negative emotions may affects eating habits in a given person.

However, due to the high and increasing prevalence of overweight/obesity worldwide and the fact that individuals with elevated depressive symptoms may be prone to overeating and exibit a preference for high-energy foods, an integral approach aimed at stress and emotion management and nutrition education may contribute to the development of healthy eating behavior 44.

Most countries have experienced nutrition transition, which is characterized by marked socio-economic transformation over recent decades. Such a transition has led to profound changes in food consumption and lifestyle patterns 45. The intake of fast food and sugar-sweetened beverages has increased drastically and the intake of milk, fruit, vegetables, and high fiber foods has decreased. Additionally, the level of physical activity has decreased and sedentary behavior has risen. This may contribute to the incidence of obesity and associated chronic diseases 46,47.

Finally, it is important to underline that information on the dietary and lifestyle patterns of young people is needed to prevent weight gain and to promote healthy food habits among the young population.

Among the limitations of the study, it should be noted that it was carried out with a specific non-clinical population (freshman students with a mean age of 19 years) and it is difficult to extrapolate the results to other population groups.

The self-reported questionnaire applied in the study for assessing depression only identifies symptoms or vulnerability to depression and does not diagnose a clinical condition. Additionally, a self-reported questionnaire may overestimate or underestimate food consumption frequency; weight and height were also self-reported. Despite this limitation, the study was carried out on a large sample of the student population, and associations were found between depression score and variables of food consumption in women, as well as between depression score and BMI. Further research with more precise techniques is required to assess the consistency of this data. Finally, longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate the long-term effect of depression on food consumption and body weight.

CONCLUSIONS

Freshman students presented a high prevalence of depression symptoms, and their diet was high in fried food, sweetened drinks and sugary food. Consumption of fast food, fried food and sweet food, as well as low exercise frequency were associated with higher depression score.

Individuals vulnerable to depression may use food for psychological comfort; therefore, an integral approach should be included in nutrition education. The efficiency of institutional programs, promotion of physical activities, and thematic workshops aimed at stress and emotion management may contribute to the development of healthy eating behaviors.