Introduction

The concept of happiness in psychology is defined as wellbeing (Diener, 2000). Today, approaching events and facts with only general psychology theories does not provide us with enough results. Therefore, in order to obtain better data, the positive psychology field started to expand and the number of publications and studies increased rapidly. Much research on wellbeing has been done to reveal the sources of happiness. The interest of positive psychology is related to subjective experiences of individuals such as wellbeing, satisfaction, hope, optimism, flow and happiness (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Associated with the concept of happiness, wellbeing consists of three basic elements. These elements are positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction (Diener, 1984). Diener (2000) explains wellbeing as “being subjective, positivity and evaluation of one’s whole life generally”. Wellbeing is a subjective assessment of individuals' positive and negative emotions and their satisfaction with life.

Research shows that wellbeing and life satisfaction develop especially four areas of the lives of individuals. These are health, work life and income, social relationships, and social benefits. Research findings indicate that wellbeing positively affects health; individuals with high level of wellbeing are healthier and have less negative physical symptoms. Similarly, it is seen that individuals with higher wellbeing enjoy their jobs more and earn more than others do (Yalçın, 2015). Diener and Ryan (2009) state that positive social relations support wellbeing by indicating that individuals with a large number of friends and family members have higher levels of wellbeing. Wellbeing is associated with negative concepts as well as positive concepts. One of these concepts is burnout.

With his article called “Staff Burn-Out”, Freudenberger (1974) introduced the concept of burnout to the literature. In this article, Freudenberger (1974) defined burnout as ‘the loss of power and energy resulting from failing, wear out, and overloading, or a state of exhaustion of one’s internal sources resulting from failing to meet the desires” (pp. 160). The concept of burnout was defined by other theorists after Freudenberger. However, the definition of Maslach (2003) has been mostly discussed in the literature. Maslach (2003) defined burnout as ‘a psychological syndrome that involves a prolonged response to stressors in the workplace’ (pp. 189). Maslach discusses the concept of burnout in three different dimensions categorizing the feelings of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment (Ergin, 1992).

Individuals with burnout exhibit physical, emotional and behavioral symptoms. Physical symptoms are observed as chronic fatigue, loss of energy, sleep disturbances and shortness of breath. Emotional symptoms are seen as lack of motivation, decrease in self-esteem, feeling of worthlessness, excessive skepticism, anxiety, restlessness, feeling isolated, quick irritation, dissatisfaction, concentration disorders, helplessness, stress, confusion, and disorder. Behavioral symptoms include sudden responsiveness and hypersensitivity to criticism, irritability, impatience, rigidity in rules, susceptibility, time spent with other things instead of dealing with work, constant defense and blame, denial, rationalization, and deterioration in relations with the environment (Arı & Bal, 2008; Kaçmaz, 2005; Lambie, 2007; Torun, 1997).

Burnout has also emerged as a factor that reduces wellbeing. The research has showed that there is a negative correlation between burnout and wellbeing (Aypay & Eryılmaz, 2011; Duran & Barlas, 2014; Özyürek, Gümüş, & Doğan, 2012). In other words, individuals' experiences of burnout lead to a decrease in their wellbeing. In psychology, not only the negative aspects of individuals such as weakness, but also positive aspects such as powerfulness and virtue should be studied (Seligman, 1998). The individuals carry their strengths and weaknesses together in life. Human is not only weak or just a strong being. Therefore, the individual can be recognized more accurately and comprehensively when the wellbeing that constitutes the strong side of the individual and the burnout that constitute the weak side are considered together. Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000) recommend studying subjects in which individuals evaluate their subjective experiences. Therefore, when the relationship between wellbeing and burnout is studied, it is a necessity to determine the variables mediating between the two. One of these mediators is cynicism.

Cynicism has been the subject of study in different disciplines of social sciences such as philosophy, religion, politics, sociology, management and psychology. In studies on cynicism, the concept of cynicism is explained by different perspectives in different disciplines (Brandes, 1997; Hançerlioğlu, 2000; Kalağan & Güzeller, 2010). The individual, who believes that individuals pursue only their own interests and accepts everyone as beneficiary, is defined as cynical and the notion trying to explain that is defined as cynicism (Erdost, Karacaoğlu, & Reyhanoğlu, 2007). General judgment about cynicism is that the principles of honesty, justice and sincerity are sacrificed to personal interests (James, 2005). When the historical process is examined, cynic individuals are also known to despise the institutions in which they work (Kalağan & Güzeller, 2010). Moreover, these individuals seek to praise themselves by despising their institutions.

Cynicism and burnout are related but distinct concepts. The literature revealed a positive relationship between burnout and cynicism (Alan & Fidanboy, 2013; Bang & Reio Jr, 2017; Billing et al., 2011; İncesu, Yorulmaz & Evirgen, 2017, Wei, Wang & Mcdonald, 2015). The concept of cynicism was used instead of depersonalization, one of the dimensions of burnout, to explain the concept of burnout (Portoghese et al., 2018). However, burnout involves the adverse attitude towards each member of the organization while cynicism involves the adverse attitude towards only the authority. In burnout, negative emotions such as disappointment and frustration are directed towards both the individual itself and the people around while these negative emotions are directed towards only authority in cynicism (Alan & Fidanboy, 2013; Salanova et. al., 2005). From a behavioral perspective, burnout frequently indicates the withdrawal behavior of employees from the organizational life. On the other hand, cynical individuals demonstrate a defensive attitude. This defensive attitude can be demonstrated by mocking the organizational activities. The literature reveals that the outcomes of burnout are harmful to health while the outcomes of cynicism might be positive (Brandes & Das, 2006). All of the above shows that burnout and cynicism are related concepts but they do not have the same meanings. However, it can be stated that individuals experiencing burnout might feel being suppressed. In other words, it can be expressed that cynicism might be playing a mediator role in predicting the happiness of individuals experiencing burnout. Indeed, the findings in the literature confirm that (Bakker et al., 2004; Billing et al., 2011; Demerouti et al., 2005).

Cynicism has various effects on individuals. Within this context, cynicism leads to effects on individuals such as emotional numbness, indifference, insecurity and lack of importance resulting from long working hours, work intensity, ineffective leadership and management, new tasks in the workplace, and shrinking organizations (Abraham, 2000; Kalağan, 2009; Wanous et al., 2000). In other words, cynicism is expressed as a general or specific attitude that includes social insecurity, disbelief, despair and disappointment towards social communities, groups, institutions, ideology or individuals (Andersson, 1996). Despair and frustration of individuals experiencing cynicism by showing submission to authority or silence in the face of injustice also leads to a decrease in their wellbeing. Undergraduates that are teacher candidates have difficulties in finding job in Turkey after graduation in addition to the problems resulting from their life period. In this period, teacher candidates may experience burnout in the face of the difficulties. The findings in the literature shows that preservice teachers experience burnout widely (Balkıs et al., 2011; Cushman & West, 2006; Santen et al., 2010; Schorn & Buchwald, 2007; Tümkaya & Çavuş, 2010). For example, Balkıs et al. (2011) found that 17% of preservice teachers had high level of burnout while 60.4% had medium level burnout. In another study, it was found that 8.6% of preservice teachers experienced high level of burnout (Tümkaya & Çavuş, 2010). Schorn and Buchwald (2007) reported that 8% of preservice teachers had high level of emotional burnout, 13% had depersonalization, and 10% perceived low personal competency. The causes of preservice teachers’ burnout have been classified into two categories, which are personal and environmental (Tümkaya & Çavuş, 2010) Personal reasons are described as choosing teaching profession unwillingly and deciding that the profession is not suitable for them after starting the education but keeping on. On the other hand, environmental causes include having difficulty in classroom management, preparation of documents, lecturing, and carrying out the responsibilities during their practice at schools as an undergraduate. Moreover, preservice teachers have to pass the Public Personnel Selection Examination so that they could be appointed as teachers. Considering that nearly one million preservice teachers take this exam and twenty thousand individuals are appointed yearly, they fear of not being appointed, and experience anxiety, depression, and hopelessness (Şanlı-Kula, & Saraç, 2016; Tümkaya, Aybek & Çelik, 2007). All of these causes indicate that preservice teachers experience burnout. On the other hand, their wellbeing may reduce because they cannot take steps to find a job and a partner which are their basic life tasks as a result of their burnout. Individuals with burnout also participate in the society as unhappy individuals. In this study, it was aimed to draw attention to this issue by determining the mediating role of cynicism between the burnout and wellbeing of university students who are teacher candidates.

Method

Participants

Convenience sampling method was used in this study. The sample of 326 volunteered teacher candidates from a university in the northwest part of Turkey was recruited between February 2018 and May 2018. The mean age of the participants was 23.14 years (Standard Deviation = 2.36) with a range from 20 to 35 years. Of these, 58% (N = 189) were female and 42% (N = 137) were male.

Measures

The data of this study was collected using the Hunter Cynicism Scale, the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, the Life Satisfaction Scale and the Burnout Scale. Detailed information concerning these measures is presented below.

Burnout Measure Short Version: Burnout was measured with the Burnout Measure Short Version (BMS) developed by Pines (2005). The BMS is a self-report questionnaire with 10 items. Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 7 (always). Items include statements such as ‘‘I feel exhausted’’. The total score of the Turkish-BMS was the sum of the 10 items ranging from 7 to 70 with higher scores indicating a higher burnout level. BMS was translated into Turkish by Tümkaya, Çam and Çavuşoğlu (2009). The Turkish version of the BMS have good construct validity and internal reliability (Cronbach’s α = .91) and test-retest reliability coefficients (α = .70). In this study, the BMS also exhibited excellent reliability (Cronbach’s α = .91).

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule: Positive and negative affect was measured with the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) developed by Watson, Clark and Tellegen (1988). The PANAS is a self-report questionnaire with 20 items and two components (positive and negative affect). Items are rated on 7-point Likert scale from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 7 (extremely). Examples of items are ‘‘interested’’ for positive affect and ‘‘distressed’’ for negative affect. PANAS was translated into Turkish by Gençöz (2000). PANAS have good construct validity and internal reliability (Cronbach’s α = .83 and .86 for positive and negative affect, respectively). In this study, the PANAS also exhibited excellent reliability (Cronbach’s α = .85 and .86 for positive and negative affect, respectively).

Life with Satisfaction Scale: Life satisfaction was measured with the Life with Satisfaction Scale (LWSS) developed by Diener, Emons, Larsen and Griffin (1985). The LSS is a self-report questionnaire with 5 items. Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Items include statements such as ‘‘in most ways my life is close to my ideal’’. The total score of the Turkish-LWSS was the sum of the 5 items ranging from 5 to 25 with higher scores indicating a higher life satisfaction level. LWSS was translated into Turkish by Dağlı and Baysal (2016). LWSS have good construct validity (χ 2 /df = 1.17, RMSEA = .03, GFI = .99, AGFI = .97, CFI = 1.00, NFI = .84 and SRMR = .019) and internal reliability (Cronbach’s α = .88) and test-retest reliability coefficients (α = .97). In this study, the LWSS also exhibited excellent reliability (Cronbach’s α = .88).

Hunter Cynicism Scale: Cynicism was measured with the Hunter Cynicism Scale (HCS) developed by Lee, Restori and Katz (2010). The HCS is a self-report questionnaire with 21 items and two components (corporate trust and Deceptive behavior). Items are rated on 7-point Likert scale from 1 (disagree) to 7 (totally agree). Items include statements such as ‘‘most politicians are honest and trustworthy’’. The total score of the Turkish-HCS was the sum of the 21 items ranging from 21 to 147 with a higher score indicates a higher cynicism level. HCS was translated into Turkish by Kiraz and Bakioğlu (2016). The Turkish version of the HCS have good construct validity (χ 2 /df = 2.35, RMSEA = .06, GFI = .88, AGFI = .85, CFI = .94, NNFI = .94 and SRMR = .06) and internal reliability (Cronbach’s α = .82) and test-retest reliability coefficients (α = .67). In this study, the HCS also exhibited excellent reliability (Cronbach’s α = .79).

Procedure

The participants completed paper-and-pencil questionnaires in a classroom environment. In the data collection process of the research, the assessment tools were prepared as a leaflet and distributed to students in a classroom environment, all of whom had volunteered to participate in the research. Before each assessment application, the researchers introduced themselves and explained the importance and purpose of the research. In addition, the researchers told the participants that there would be no individual evaluation and no requirement for identity information and that the results would be used for scientific purposes only. The participants were allowed to answer the questionnaires at their own pace and typically took about 20 minutes to complete all of the sections.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analysis and correlation analysis were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine the measurement model and mediation models in AMOS Graphics. Further analyses for internal consistency and discriminant validity were conducted through MS Excel. We tested the structural model using maximum likelihood estimation. Item parceling method was used in order to reduce the number of observed variables and to improve reliability and normality of the resulting measures (Nasser-Abu Alhija & Wisenbaker 2006). Besides, item parceling method allows us to control for inflated measurement errors due to multiple items for the latent variable (Little et al., 2002). Two item parcels for Burnout Measure Short Version were created by using an item-to construct balance approach the goal of which is to derive parcels that are equally balanced with regard to their difficulty and discrimination (Little et al., 2002).

Several indices of goodness-of-fit were used as criteria for the above model selection. We used χ2/df< 5, CFI, TLI, GFI, IFI >.90, SRMR and RMSEA <.08, as the assessment standards of the model fit index (Hu & Bentler, 1999; MacCallum et al., 1996; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). A bootstrap analysis was conducted in order to determine the mediator role of cynicism in the relationship between burnout and wellbeing (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). The Bootstrapping Confidence interval was estimated in the indirect impact of burnout on wellbeing. 10000 resampling and 95% confidence intervals were used in this process.

Results

Measurement Model and CFA

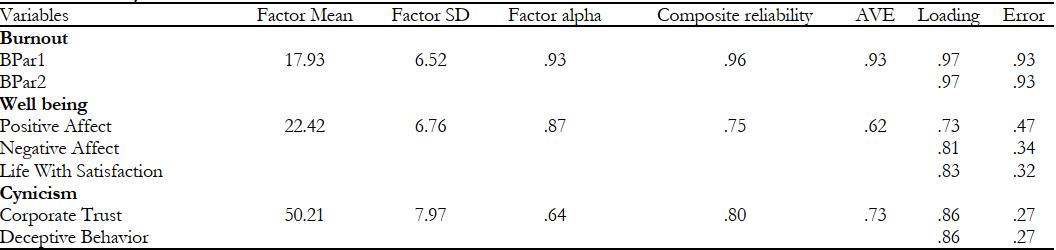

First, we tested the measurement model to assess whether each of the latent variable was represented by their indicators. The measurement model consisted of three latent factors, burnout, wellbeing and cynicism, and seven observed variables. The measurement model test indicated a satisfactory model fit:χ 2 (11, N = 326) = 21.950, p<.001; χ 2/df= 1.995; GFI = .98; CFI = .99; NFI = .98; TLI = .98; SRMR = .023; RMSEA =.055. The summary of the CFA are presented in Table 1.

As summarized in Table 1, each latent variable had adequate number of items for an acceptable measure (i.e., ≥3; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007) along with plausible internal consistency indices (≥ 0.70; Huck, 2012; Nunnally, 1978) and factor loadings (i.e., ≥ 0.32; Worthington & Whittaker, 2006). The measurement model explained 78.18% of the total variance which was considered plausible since it exceeded 50% (Henson & Roberts, 2006). Convergent and discriminant validity concerns were addressed to see the extent to which current variables shared their variance and how they differed from other measures (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). In addition to plausible composite reliability coefficients (i.e., ≥0.70; Nunnally, 1978), the shared variance between factors was examined with the average variance extracted (i.e., AVE), which exceeded 0.50 in most measures. The square roots of these values were calculated for all factors, which were bigger than their correlations with other factors, suggesting ideal discriminant validity. The factor loadings of all the indicators were significant (ranging from .59 to .87, p < .001), demonstrating that respective indicators are true representative of their latent factors.

Preliminary Analyses

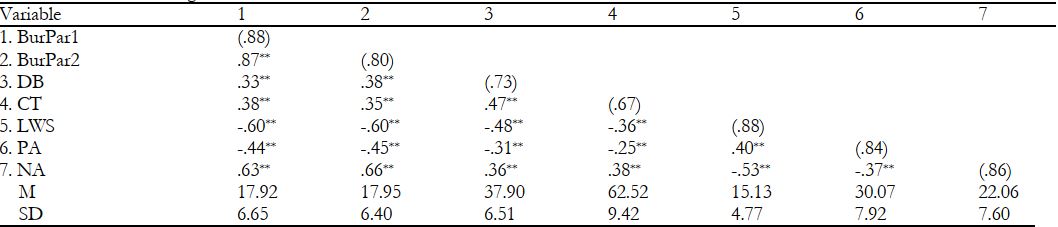

The relationships among burnout, wellbeing, and cynicism levels of teacher candidates were analyzed using structural equation modeling. The analysis was performed in two steps. In the first step, descriptive statistics were determined. In the second step, the hypothesized model was tested. The correlations among the variables of interest are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Correlations among the variables of interest.

Note.**p<.01, BurPar burnout parcels, DB deceptive behavior, CT corporate trust, LWS life with satisfaction, PA positive affect, NA negative affect, M mean, SD standard deviation. AVE’s square root is in parentheses.

When Table 2 is examined, it can be seen that there is a significant positive correlation between burnout parcels and cynicism (corporate trust and deceptive behavior) (r = .33 ≤ r ≤ .38, p < .01) and between burnout parcels and negative affect (r = .60 ≤ r ≤ .66, p < .01). There was a significant negative correlation between burnout parcels and life satisfaction (r = -.60, p < .01). There was a significant negative correlation between burnout parcels and positive affect (r= -.45 ≤ r ≤ -.44, p < .01). There was a significant positive correlation between cynicism and negative affect (r = .36 ≤ r ≤ .38, p < .01. There was a significant negative correlation between cynicism and life with satisfaction (r = -.48 ≤ r ≤ -.36, p< .01). There was a significant negative correlation between cynicism and positive affect (r = -.31 ≤ r ≤ -.25, p < .01). The square root of the AVE coefficients among the variables of the study ranged from .67 to .88.

Main Analyses

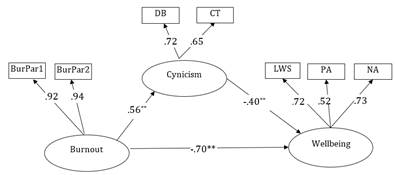

In the second phase of the study, the structural equation model was tested in order to determine the mediator role of cynicism in the relationship between burnout and wellbeing. The results are presented in Figure 1.

All path coefficients were observed to be significant in the analysis. Burnout predicted wellbeing negatively (β = -.70, p < .01) and cynicism positively (β = .56, p < .01). In addition, cynicism predicted wellbeing negatively (β = -.40, p < .01). Moreover, the effect coefficient of burnout predicting wellbeing through the mediation of cynicism was estimated to be -.39.

When the fit indexes of the model were examined, all of them were found to be at acceptable levels. The fit indexes were as follows: χ 2 (11, N = 326) = 21.950, p<.001; χ 2/df= 1.995; GFI = .98; CFI = .99; NFI = .98; TLI = .98; SRMR = .023; RMSEA =.055. Therefore, it can be stated that the structural equation model was confirmed.

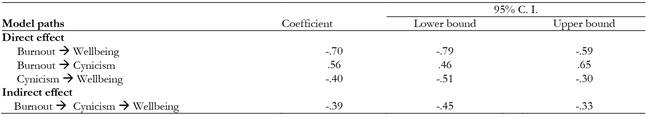

10,000 resample bootstrapping was conducted in order to provide additional evidence related to the significance of direct and indirect effects. The bootstrapping coefficients and the lower and upper bounds of 95% confidence intervals are presented in Table 3.

When Table 3 is examined, it can be seen that all of the effects in the structural equation model were significant. The bootstrapping confidence intervals lower and upper bounds of both the direct and indirect effects comprise not zero. Therefore, it can be stated that the teacher candidates’ burnout had an effect on their wellbeing through the mediation of cynicism according to the bootstrapping results.

Discussion

Happiness occurs with the pleasure of the individual's life. Individuals who are happy are more productive and they are the individuals who can look positively to life. On the contrary, individuals with burnout are unhappy. In this study, the mediator role of cynicism in the relationship between burnout and wellbeing of Turkish University students was investigated. As expected, the results show that the cynicism plays a mediator role in the relationship between burnout and wellbeing. Accordingly, cynicism is positively correlated with burnout and burnout negatively predicts wellbeing. In short, it can be expressed that as the university students’ cynicism level increases, their burnout level increase and wellbeing level increase, and vice versa.

In this study, a negative correlation was found between burnout and wellbeing. When the findings in the literature were examined, it was observed that they were similar to the current findings (Aypay & Eryılmaz, 2011; Burke, Koyuncu & Fiksenbaum, 2010; Duran & Barlas, 2014; Hall et al., 2016, 2017; Özyürek, Gümüş, & Doğan, 2012). Burnout as a negative concept is seen as a factor that decreases wellbeing. In fact, individuals who experience burnout experience emotionally loss of self-confidence, extreme skepticism, anxiety, dissatisfaction, helplessness, and stress. (Arı & Bal, 2008; Kaçmaz, 2005; Lambie, 2007; Torun, 1997). Individuals’ negative emotions cause them to be unhappy. Therefore, their wellbeing level decreases as the level of burnout decreases.

Another finding of this study was the positive relationship between cynicism and burnout. The literature is consistent with this finding (Bang & Reio Jr, 2017; Billing et al., 2011). It is observed that cynical individuals exhibit the desired behaviors instead of activating their own resources and become alienated from them. Therefore, self-alienated individuals also experience burnout. Cynical individuals also abandon honesty, justice and sincerity in order to pursue their own interests (James, 2005). Individuals who do not use their own resources take others as a reference for their behavior. In this case, it is inevitable for the individual to experience burnout.

In this study, cynicism was found to be a mediator between burnout and subjective wellbeing. There are some studies in the literature revealing the mediator role of cynicism among the workers’ burnout, prosocial behaviors and work performance (Bakker et al., 2004; Billing et al., 2011; Demerouti et al., 2005). Individuals with burnout exhibit sudden reaction, hypersensitivity to criticism, nervousness, rigidity in rules, susceptibility, persistent defense, and blame behavior (Arı & Bal, 2008; Kaçmaz, 2005; Lambie, 2007; Torun, 1997) and their wellbeing reduces. Cynicism is seen as a form of defense developed by individuals against unstable and unsafe living and working conditions (Mirvis & Kanter, 1989, 1991). Moreover, cynicism is a cognitive shield that protects the individual in stressful situations (Cartwright & Holmes, 2006). Individuals protect themselves by exhibiting cynicism towards submission to work performance while coping with the feelings of burnout caused by long-term stress (Taris et al., 2005). However, high level of cynicism affects the work performance of individuals negatively (Brandes & Das, 2005). In their study, Schaufeli, Taris and Van Rhenen (2008) found a positive relationship between the levels of cynicism and burnout of the employees and a negative relationship with job satisfaction. Individuals engaged in a job are happier. However, the fact that employees feel under pressure and that the employer wants to behave in a way that causes burnout and ingestion makes them feel unhappy.

This research was carried out with university students who were teacher candidates. Teacher candidates are experiencing difficulties in finding a job after graduation in Turkey. The main difficulties experienced by them are the lower number of assignments than the number of graduates in Turkey, Public Personnel Selection Examination, and the interviews conducted during assignments. Teacher candidates are required to obtain an adequate score from Public Personnel Selection Examination first, and then to pass the interview in order to be assigned as a teacher. In order to have a job, teacher candidates have to prepare for the exam in order to distinguish themselves from many competitors. Studying hours and intensity to get sufficient score in the exam can cause emotional burnout. On the other hand, the teacher candidates who have enough scores should have the required performance during the interview in order to be employed. During the interview, teacher candidates adopt a cognitive strategy risking self-alienation in order to have a job. Self-alienation paves the way for being unhappy. In the study conducted by Gün (2015), it was found that there was a positive medium level relationship between the general organizational cynicism attitudes and emotional exhaustion levels of the lecturers. Likewise, both the need to deal with an intense studying tempo to get sufficient score from the Public Personnel Selection Examination and the anxiety of not being able to pass through the interview cause teacher candidates to feel pressured leading them to experience burnout and digestion and to be unhappy.

Conclusion

In this study, it was concluded that cynicism played a mediator role between burnout and wellbeing. Wellbeing of individuals experiencing burnout reduces. Moreover, individuals with burnout may exhibit suppressive behaviors. Suppressed individuals tend to obey and remain silent in the face of an authority. Thus, suppressed individuals avoid exhibiting the behaviors expected of them and ignore their own power/existence. Especially teacher candidates should be supported to express their own ideas when they think that they are right and against injustice. Not only university administrations but also nongovernmental organizations should create environments for undergraduates to demonstrate their potentials and provide them with opportunities.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study provides an empirical data on the association between burnout, and wellbeing through cynicism among Turkish university students, several limitations to this study are worth noting. The first limitation was the characteristics of sample and sample size. The current study which limits the generalizability of the results was based on Turkish university students. Thus, using different populations or larger samples could be helpful to improve the generalizability. Second limitation was variables which are considered as mediators. Other meditation models in which different mediation variables are considered rather than cynicism may be examined on the link between burnout and wellbeing. Third limitation was data collection process. Self-report measures were used to collect the data. Hence, different methods might be used to collect data. Last limitation was the cross-sectional design of the study which cannot support causal inferences. Future studies which may use different designs like a longitudinal design may help to clarify causal directions.