Introduction

The new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has become a pandemic that affects health and well-being worldwide. The global pandemic has forced many countries to introduce lockdown measures to minimize the spread of the virus. The period of lockdown represents a radical change in people's lifestyles, an interruption of the usual daily activities.

On 30 January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak of the disease caused by the COVID-19 coronavirus an international public health emergency and, on March 11, a global pandemic. In Spain, the government decreed the state of alarm on March 14 (Real Decreto 463/2020), and a period of mandatory lockdown was imposed throughout the Spanish territory from March 14 to May 3 to slow down and minimize the expansion of the coronavirus and reduce the health emergency. The lockdown restricted free movement in public areas an prohibi-ted all non-essential commercial, educational, work, and social activities.

Quarantine and isolation are adopted to protect people's physical health when there is a risk of infectious diseases, but it is essential to take into account the implications for the mental health of the people undergoing such restrictions (Hossain et al., 2020). Public health emergencies can affect the health, safety, and well-being of individuals and communities (Pfefferbaum & North, 2020). Although these measures may be critical to mitigate the spread of this di-sease, they will certainly have consequences for mental health and short- and long-term well-being (Galea et al., 2020).

Well-being assessment is a key aspect when evaluating the socio-psychosocial impacts on health emergency contexts. Most studies investigating the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the general public have used cross-sectional designs and have no control groups (Prati & Mancini, 2021). Several cross-sectional studies show that the COVID-19 pandemic has decreased subjective well-being (Ahuja et al., 2021; Yıldırım & Arslan, 2020).

Bendau et al. (2021) indicate that, although cross-sectional studies provide an important and timely first comprehension of the consequences of the pandemic on mental health, they have some shortcomings. According to these authors, the COVID-19 pandemic is a very dynamic situation in which the consequences for mental health can change ra-pidly, for example, due to changes in the number of cases, changes in government restrictions, habituation, or changes in media coverage and, therefore, longitudinal investigations with repeated measurements are needed to understand the progress of the psychological consequences of the pandemic.

The recent and only review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies on the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, conducted by Prati and Mancini (2021), had the following inclusion criteria: (a) longitudinal designs evalua-ting psychological functioning before and after the COVID-19 lockdowns using the same instruments; (b) natural expe-riments comparing participants who were confined to those who did not have such restrictions; (c) natural experiments with at least two (i.e., before and during the COVID-19 pandemic) cross-sectional data collection points (with diffe-rent individuals) in which samples were compared or collec-ted using the same methodology. They found only 25 articles, of which six studies reported the effects on positive psychological functioning (e.g., well-being, life satisfaction) and three studies on loneliness and suicide risk; these authors indicated that the meta-analytical findings show a small but significant effect of the COVID-19 lockdowns on mental health symptoms among the general population. Subgroup analyses indicated that depression and anxiety showed consistently small but significant effects of confinement. However, they found no evidence that the confinements reduce positive psychological functioning, such as well-being or satisfaction with life, and concluded that the psychological impact of COVID-19 confinement is small in magnitude and very heterogeneous, suggesting that it has no uniformly harmful effects on mental health and that most people are psychologically resistant to such effects (Prati & Mancini, 2021).

There is little agreement about the structure and content of well-being, as reflected by the number of theories and models that exist (for a review, see Jayawickreme et al., 2012) but there is at least agreement that well-being is a complex and multidimensional construction. In a recent study on the concept of well-being, Martela and Sheldon (2019) indicated that it has been operationalized in at least 45 different ways and that measures of at least 63 different constructs have been used. They pointed out that, while the most common way to conceptualize well-being is subjective well-being, a category that includes positive affect, negative affect, and satisfaction with life, many researchers consider that satisfaction with life and affect should be complemented by the dimension of eudaimonic well-being. Some theories focus on emotion (hedonic well-being), some emphasize eudaimonic elements, and others combine hedonic and eudaimonic domains (Ryan & Deci, 2001). While hedonic and eudaimonic conceptions of well-being have always been considered separate, in recent years the unilateral approach of the study of well-being has aroused interest (Kashdan et al., 2008; Henderson & Knight, 2012).

The best well-being model does not exist, but different conceptualizations can help examine the abstract construct of well-being and provide specific domains that can be measured and developed. Instruments based on a strong re-ference theory also relate to different concepts of well-being, particularly according to the theoretical reference paradigm, either hedonic or eudaimonic. In many multidimensional theories of well-being, efforts are being made to integrate and investigate the main components of well-being (Forgeard et al., 2011; Hone et al., 2014; Butler & Kern, 2016).

The most recent operational theory of well-being was proposed by Seligman (2011) and it recognizes five pillars of well-being, which create the acronym PERMA: Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment. This theory conceptualizes well-being holistically, as flourishing, and combines multiple hedonic and eudaimonic dimensions (Butler & Kern, 2016; Sun et al., 2018; Giangrasso, 2021). It is one of the main conceptualizations and operationalizations of the flourishing construct (Hone et al., 2014). Drawing on this theory, Butler and Kern (2016) developed a multidimensional measuring instrument called the PERMA-Profiler to evaluate well-being in multiple fields.

Martela and Sheldon (2019) pointed out that the diverse well-being measurement strategies often coincide very little with each other, leading to different outcomes and making it difficult to compare the conclusions of different studies. Most studies conducted to analyze the consequences of the lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic on well-being have assessed subjective well-being and, in quite a few cases, with very few items. We found no studies that measure hedonic and eudaimonic well-being as broadly as they are assessed with the PERMA-Profiler.

Optimism is related to well-being but there are still no generally accepted definitions of optimism and pessimism. The most popular view is Scheier and Carver’s (1985) definition of dispositional optimism (and pessimism), referring to generalized expectancies of positive and negative outcomes in one’s life. The widely used Life Orientation Test (LOT, Scheier & Carver, 1985; LOT-R, Scheier et al., 1994) is based on this definition. They also suggested that optimists report higher subjective well-being because they handle critical life situations better than pessimists (Scheier et al., 1986; Scheier & Carver 1993).

There are quite a few studies that report strong relationships between optimism and subjective well-being (for a review, see Carver & Scheier 2002). Several researchers have studied the relationship between dispositional optimism and well-being, considering that dispositional optimism can be used to predict subjective well-being, or that it is an influential factor of subjective well-being, or that it predicts various aspects of subjective well-being (e.g., Chang & Sanna, 2001; Diener et al., 2003; Hanssen et al., 2015; Pacheco & Kamble, 2016; Yu & Luo, 2018).

The main objective of this longitudinal study, with two repeated measurements, one before the lockdown and one during the lockdown, carried out with the same participants, is to investigate the impact of the confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being levels, as well as to determine the evolution of these levels of well-being from the first measurement to the se-cond.

Available cross-sectional studies on COVID-19 and mental health cannot report longitudinal changes in the mental health outcomes of the confined people. Added to this, they do not contemplate an overview of the welfare cons-truct.

We intended to obtain an overview of the evolution of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, to determine possible changes in any of the domains of well-being due to confinement, and the impact of confinement on people who have not had COVID-19 but who have been confined for several weeks. We also explore the effect of the level of dispositional optimism, age, and gender, as possible moderating variables on the well-being values of the participants during the lockdown.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Six-hundred and thirty university students were asked to participate in the online study. The first measurement was made in early March 2020 (March 2-8), a week in which there was no public notice that lockdown measures could be established in the following weeks. The second measurement was made at the end of April 2020 (April 20 to 26). At this time, the population had already been under mandatory confinement since March 14, when the Spanish government declared the alarm state and began a period of national mandatory lockdown, which lasted until May 3.

A total of 303 participants completed both measurements. Their mean age was 36.54 years (SD = 11.09), age ranging between 18 and 69 years. There were 60 (19.8%) men in the sample, mean age 40.48 years (SD = 11.41), age range between 19 and 66 years, and 243 (80.2%) women, mean age 35.57 years (SD = 10.82), age range between 18 and 69 years.

These participants were recruited from the National University of Distance Education (UNED) and volunteered to take part in this study. Due to the characteristics of the UNED, the participants study and work, practice different professions, live in urban and rural environments, and have a very wide age range.

All individuals gave their written informed consent to participate in the study. The data provided were anonymous and were treated according to Spanish law regarding general data protection. This study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and ethical guidelines.

Measures

The PERMA-Profiler

The PERMA-Profiler (Butler & Kern, 2016) was deve-loped to measure Seligman’s (2011) PERMA model of flou-rishing. Seligman’s (2011) PERMA model advocates that flourishing arises from five well-being pillars or domains: Positive Emotion (P), Engagement (E), Relationships (R), Meaning (M), and Accomplishment (A), abbreviated as the acronym PERMA, which groups together the five main factors on which the model is based. Focusing on the five domains defined by the PERMA theory of Seligman (2011) and through an extensive theoretical and empirical process, Bu-tler and Kern (2016) developed and validated the PERMA-Profiler, a measure that evaluates well-being in the five domains. Seligman (2011) suggested that these five domains can be defined and measured as separate but correlated

constructs.

The PERMA-Profiler contains 23 items, of which 15 items represent the five PERMA domains, and each domain is evaluated through 3 items. Positive Emotion (P): general tendencies toward feeling contentment and joy. Engagement (E): being absorbed or interested in an activity, a state of flow. Relationships (R): feeling loved, supported, and valued by others. Meaning (M): having a sense of purpose in life. Accomplishment (A): feelings of accomplishment and sta-ying on top of daily tasks.

Besides PERMA's 15 items, the measure includes 8 filler items, which aim to disrupt response trends and provide additional information about participants. The 8 filler items comprise an element that evaluates overall happiness (Happiness), three elements of negative emotions that evaluate a tendency to feel sad, anxious, and angry (Negative Emotion), an element that evaluates loneliness (Loneliness) and three elements that evaluate self-perceived physical health and vitality (Physical Health). A general well-being score (Overall Well-being, PERMA) is also calculated by adding items from the five PERMA domains and the Happiness item. Butler and Kern (2016) pointed out that the 15 PERMA questions (3 for each of the five PERMA domains) could be used as a brief form, but they recommend applying the full measure with the 23 questions. Each item is scored on an 11-point Likert-type scale anchored by 0 (never) to 10 (always), 0 (not at all) to 10 (completely), or 0 (terrible) to 10 (excellent), depending on the item content. Scores are calculated as the average of the items comprising each domain.

The PERMA-Profiler has shown acceptable psychome-tric properties in evaluations performed with several different international samples (Butler & Kern, 2016), and most of the data available concerning the psychometric properties are found in the original study of its development and validation (Butler & Kern, 2016). Butler and Kern (2016, p. 22) concluded that “through an intensive process, we created a measure that, at both content and analytical levels, captures the five PERMA domains. The measure demonstrates acceptable reliability, cross-time stability, and evidence for convergent and divergent validity”.

Despite its recent publication, the reliability and validity of the PERMA-Profiler have also been established in other cultural contexts, and it has been translated into foreign languages for use with different populations (Iasiello et al., 2017; Ayse, 2018; Sun et al., 2018; Pezirkianidis et al., 2021; Ryan et al., 2019; Wammerl et al., 2019; Cobo-Rendón et al., 2020; Giangrasso, 2021). In addition to the validity results provided by the authors Butler and Kern (2016), in regard to the convergent validity of the questionnaire, for example, Wammerl et al. (2019) and Giangrasso (2021), find that the domains of the PERMA-Profiler (P, E, R, M and A) showed consistently positive correlations with the Psychological Well-Being-Scales (PWB; Ryff & Keyes, 1995); Goodman et al. (2018) and Pezirkianidis et al. (2021) showed positive co-rrelations with the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985).

The PERMA-Profiler was translated into Spanish follo-wing the International Test Commission Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests (International Test Commission (ITC), 2017). Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency was calculated as a measure of reliability for each of the domains and the Overall Well-being (PERMA) score, Table 1 presents the results of internal consistency in the population of this study, at the two measurements, M1 and M2.

Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R)

The Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R) was deve-loped by Scheier et al. (1994). This scale was designed to assess generalized expectations of positive and negative outcomes. The LOT-R is a short instrument consisting of 10 self-report items. Only 6 of the 10 items are used to derive an optimism score. The remaining 4 items are filler items. Of the 6 items, 3 are worded in the positive direction (direction of optimism), and 3 in the negative direction (direction of pessimism).

In this study, we used the version adapted for the Spa-nish population of the LOT-R (Otero et al., 1998; Ferrando et al., 2002). Participants are asked to indicate the degree of agreement with each item through a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Items drafted negatively are reversed and their score is added to the items written positively, leading to a total score orien-ted towards the optimism pole. Scores can range from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating higher levels of dispositional optimism. Researchers sometimes split the Life Orientation Test-Revised into 2 subscales, one consisting of only positively valenced items and the other consisting of only negatively valenced items. We chose not to create subscales for theoretical and methodological reasons (Ryff & Singer, 2007; Segerstrom et al., 2011). Optimism is most accurately captured by a scale that combines positively worded items that are endorsed and negatively worded items that are rejected (Ryff & Singer, 2007). Furthermore, it is increasingly apparent that this separation into subscales may be at odds with the goal of controlling for acquiescence response bias in the measurement of psychological constructs (Kim et al., 2014). Thus, following recent theorizing and work in this a-rea, we used the 6-item composite, rather than creating two 3-item subscales (Segerstrom et al., 2011; Boehm et al., 2013; Cano-García et al., 2015). In a review, the authors of the test continue to recommend that the LOT-R be used as a one-dimensional scale (Carver et al., 2010).

The psychometric properties of the LOT-R have been well documented by the creators of the instrument (Scheier & Carver, 1985; Scheier et al., 1994). A meta-analytic study on the internal consistency of the LOT-R yielded a mean alpha coefficient of .73 (Vassar & Bradley, 2010). The LOT-R has become one of the most widely used measures to assess optimism. Its reliability and validity have been established in other cultural contexts and it has been adapted to many languages such as German (Glaesmer et al., 2012; Hinz et al., 2017), French (Trottier et al., 2008), Japanese (Sumi, 2004), Greek (Lyrakos et al., 2010), Portuguese (Laranjeira, 2008), Brazilian Portuguese (Roat el al., 2014), Serbian (Jovanović & Gavrilov-Jerković, 2013), Latin American Spanish (Vera-Villarroel et al., 2009; Zenger et al., 2013), and Spanish from Spain (Ferrando et al., 2002; Cano-García et al., 2015).

Table 1 presents the results of internal consistency in the population of this study, in the first measurement performed, M1.

Statistical Analysis

For all data analyses, we used the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM Corp. Released, 2017), and we used the SPSS PROCESS Macro (Hayes, 2018) to examine the effect of moderator variables. PROCESS is an SPSS macro for mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling.

To obtain the relationships between the domains and between domains and the Overall Well-being score (PERMA) at each measurement, we calculated Pearson product-moment correlations (two-tailed).

To analyze the mean differences of the domains and the Overall Well-being (PERMAscore), between the first and second measurements (M1 versus M2), we used Student's t-test for paired samples.

To examine the possible moderation effect of optimism, age, and, gender in the relationship between the scores of the domains at the first measurement and the second measurement, we applied Model 1 in PROCESS (simple moderation model), with a 95% confidence interval and 10000 bootstrapping samples, and applying pick-a-point approximation techniques for the variable gender, and pick-a-point and Johnson-Neyman for the variables optimism and age (Hayes, 2018). These are moderation analyses of effects in within-subject designs (Judd et al., 2001).

Results

Descriptive statistics

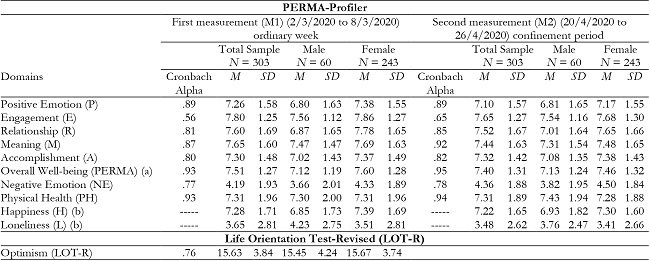

Cronbach alphas, means, and standard deviations were calculated for each domain in each of the two measurement periods and for optimism at the first measurement. Table 1 presents the results for the total sample of participants and by gender. All the internal consistency values were within acceptable levels.

Table 1: Cronbach´s alphas, means, standard deviations of the variables examined.

Note:(a) Overall Well-being (PERMA) is the average of the main 15 PERMA items and the happiness item.The 15 main items of PERMA are the items of the following domains: Positive Emotion (P), Engagement (E), Relationship (R), Meaning (M) and Accom-plishment (A)(b) Domains with a single item, the alpha of Cronbach is not obtained

Relationships between well-being domains within each measurement

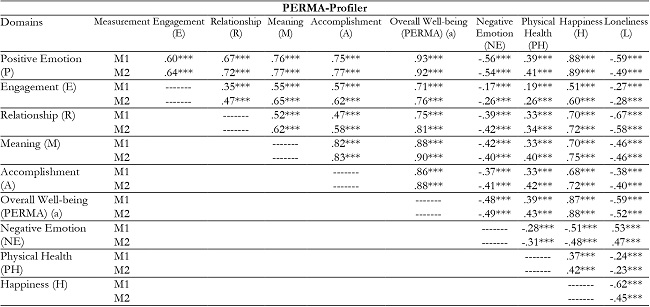

Within each measurement, M1 and M2, we calculated the correlation matrix between the domains, and between domains and the Overall Well-being (PERMA) score. The results can be seen in Table 2. All correlations were significant (p ≤ .001) at both the M1 and M2 measurements. The relationships between the domains, and between domains and the Overall Well-being (PERMAscore), were similar at both the M1 and M2 measurements, establishing identical relationships between them.

Table 2: Correlations between domains in each measurement.

N = 303;

***p ≤ .001.

M1= First measurement (2/3/2020 to 8/3/2020), ordinary week. M2= Second measurement (20/4/2020 to 26/4/2020), confinement period

Note:(a) Overall Well-being (PERMA) is the average of the main 15 PERMA items and the happiness item.The 15 main items of PERMA are the items of the following domains: Positive Emotion (P), Engagement (E), Relationship (R), Meaning (M) and Accom-plishment (A)

Positive correlations were established between the domains of Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, Accomplishment, Physical Health, Happiness, and Overall Well-being (PERMA). In turn, they all correlated negatively with the Negative Emotion and Loneliness domains. Finally, Negative Emotion and Loneliness were positively related with each other.Differences between Well-being domains when comparing both measurements

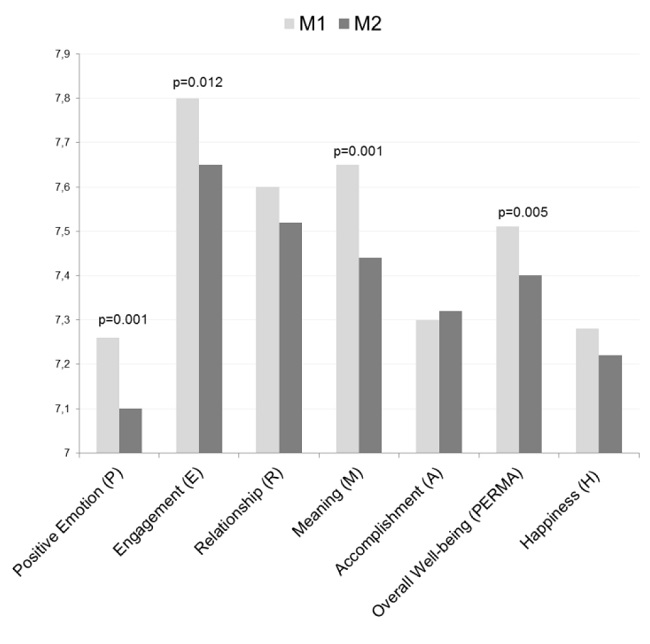

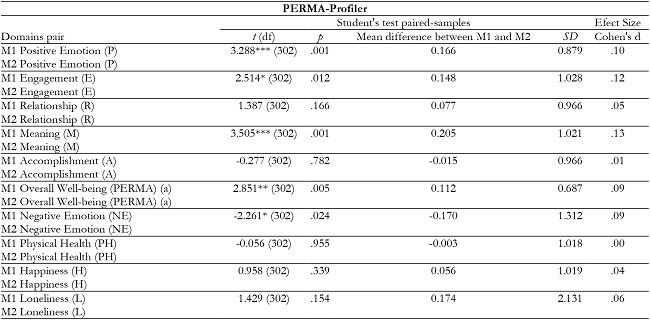

The results of the analysis of the mean differences bet-ween the M1 and M2 measurements in the domains and the Overall Well-being (PERMA) score, can be seen in Table 3. There were significant differences between the mean scores at the two measurements, M1 and M2, in four domains: Po-sitive Emotion, Engagement, Meaning, and Negative Emotion, and in the Overall Well-being (PERMA) score. The Positive Emotion domain, t(302) = 3.288, p = .001, presen-ted a higher mean score at the M1 (M = 7.26, SD = 1.58) than at the M2 (M = 7.10, SD = 1.57). The Engagement domain, t(302) = 2.514, p = .012, presented a higher mean score at the M1 (M = 7.80, SD = 1.25) than at the M2 (M = 7.65, SD = 1.27). The Meaning domain, t(302) = 3.505, p = .001, had the highest mean score at the M1 (M = 7.65, SD = 1.60) versus the M2 (M = 7.44, SD = 1.63). The Negative Emotion domain, t(302) = -2.261, p = .024, presented a lower mean score at the M1 (M = 4.19, SD = 1.93) than at the M2, (M = 4.36, SD = 1.88). Finally, the Overall Well-being (PERMA) score, t(302) = 2.851, p = .005, had a higher mean score at the M1 (M = 7.51, SD = 1.27) than at the M2 (M = 7.40, SD = 1.31).

Table 3: Analysis of the differences between the two measurement (M1 and M2) in the variables studied.

N=303; ***p ≤ .001; **p ≤ .01; *p ≤ .05

M1= First measurement (2/3/2020 to 8/3/2020), ordinary week. M2= Second measurement (20/4/2020 to 26/4/2020), confinement period

Note: (a) Overall Well-being (PERMA) is the average of the main 15 PERMA items and the happiness item.The 15 main items of PERMA are the items of the following domains: Positive Emotion (P), Engagement (E), Relationship (R), Meaning (M) and Accom-plishment (A)

Figure 1 shows a graphic representation of the mean scores obtained at the first (M1) and the second measurement (M2).

Simple Moderation: Dispositional Optimism, Age, and Gender as Moderators of Well-Being

We examined whether the variables dispositional optimism, age, and gender have a moderating effect between the scores obtained at the first and second measurements. The moderation issue concerns factors that affect the magnitude of that effect (Judd et al., 2001). We applied Model 1 in PROCESS (simple moderation model) separately for each domain and the Overall Well-being (PERMA) score, for the three variables considered moderators.

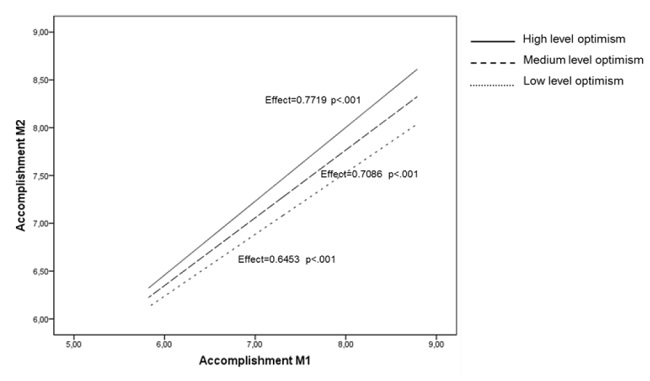

Moderation analyses revealed an interaction of the mo-derating variable dispositional optimism with the domain of Accomplishment, R2 change due to the interaction = .0063, F(1, 299) = 4.9812, p = .0264. The significant value obtained in this interaction indicates the presence of a moderation effect of Optimism on the domain of Accomplishment during confinement. The pick-a-point technique offers three levels of the moderating variable Optimism. People with low optimism = 11.7880 (Effect = .6453, se (standard error) = .0432, t = 14.9403, p < .001, LLCI (Lower Limit of the Confidence Interval) = .5603, ULCI (Upper Limit of the Confidence Interval) = .7303), with a medium level of optimism = 15.6304 (Effect = .7086; se = .0404, t = 17.5180, p < .001, LLCI = .6290, ULCI = .7882), and with a high level of optimism = 19.4727 (Effect = .7719, se = .0549, t = 14.0588, p < .001, LLCI = .6638, ULCI = .8799). The results show that optimism had moderator effect on the Accomplishment domain during confinement in all people, as all three levels generated from this moderating variable were significant. The Johnson-Neyman technique did not provide results, as there were no statistical significance transition points within the observed range of the moderator. The effect of the previous score of the Accomplishment domain on the Accomplishment score due to confinement is moderated by the person's level of optimism. The graphic representation of this interaction with the low, medium, and high optimism values generated by the technique can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Dispositional Optimism as moderators of Accomplishment. First measurement (M1) (March 2-8, ordinary week) and second measurement (M2) (April 20-26, confinement period).

Concerning the moderator variable gender, the moderation analyses revealed an interaction of gender with the Happiness domain, R2 change due to the interaction = .0056, F(1, 299) = 5.1626, p = .0238. The significant value of this interaction indicates the presence of a gender moderation effect during confinement in the Happiness domain. The pick-a-point technique shows the following result in men: Effect = .9367, se = .0713, t = 13.1341, p < .001, LLCI = .7963, ULCI = 1.0770; and in women: Effect = .7551, se = .0360, t = 20.9561, p < .001, LLCI = .6842, ULCI = .8260. Therefore, the effect of the previous score of the Happiness domain on the Happiness score due to confinement was mo-derated by being male or female. The graphic representation of this interaction with the values generated by the program can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Gender as moderators of Happiness. First measurement (M1) (March 2-8, ordinary week) and second measurement (M2) (April 20-26, confinement period).

When examining the means of men and women in the domain of Happiness, at the first (M1) and second mea-surement (M2), we observed a different evolution in the two genders. In men, Happiness increased during the lockdown, the mean of the M1, before confinement was M = 6.85 (SD = 1.73) and, at the M2, when people had already been confined for about six weeks, it was M = 6.93 (SD = 1.82). In women, the opposite was observed, during the lockdown, happiness decreased, the mean at the M1 was M = 7.39 (SD = 1.69) and at the M2, it was M = 7.30 (SD = 1.60).

Concerning age, moderation analyses showed no significant interaction between age and any of the domains, or with the Overall Well-being (PERMA) score.

Discussion and Conclusion

The purpose of this longitudinal work was to examine the effects of the lockdown on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, with two repeated measurements using the PERMA-Profiler (Butler & Kern, 2016), one made before the lockdown and one during the lockdown, and to know the effect of the level of optimism, age, and gender, as moderating va-riables of well-being.

The lockdown situation did not affect well-being in its entirety. The comparison of the mean domain scores and the Overall Well-being (PERMA) score at the two measurements (M1 and M2) yielded significant differences in four domains: Positive Emotion (experience of positive emotions), Engagement (engaging in life activities, character strength, and ability), Meaning (working towards a larger goal, feeling part of a larger purpose), and Negative Emotion (tendency to feel sad, anxious, and angry), and in the Overall Well-being (PERMA) score. In these well-being domains, the results show that the mean score was higher at pre-lockdown (M1) than during the lockdown (M2), when people had already been confined for six weeks. In contrast, in the Negative Emotion domain, the mean score was higher during the lockdown than at pre-lockdown.

We found no significant differences between the two measurements (M1 and M2) in the domains of Relationships (having satisfactory relationships with others), Accomplishment (feelings of achievement, and achieving successes regularly), Physical Health (self-perceived physical health and vitality), Happiness (general happiness), or Loneliness.

The well-being results of this longitudinal study cannot be compared with the results obtained in other studies, as none of them have evaluated all these domains of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being at two different times, before and during the lockdown. However, we can partially compare some of our results with the few longitudinal studies that have generally measured subjective well-being or psychological well-being. Kimhi et al. (2020) conducted a longitudinal study with two repeated measurements made at the end of the first wave of the pandemic and the beginning of the se-cond wave in a sample of Israeli Jewish respondents. Among other variables, they evaluated subjective well-being, using their own 9-item scale on individuals' current perception of their life in various contexts, such as work, family life, health, free time, and others. Their results show a significant decrease in the subjective well-being indicators in the second wave, second measurement, compared to the first wave, first measurement.

Sønderskov et al. (2020), in their study measuring the level of psychological well-being in Denmark during the COVID-19 pandemic and comparing it with previous Da-nish data obtained with the same measure, the five-item WHO-5 Well-being scale (Topp et al., 2015), concluded that the results suggest that the psychological well-being of the Danish population, in general, was adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and more so in women than in men.

On another hand, other studies found an increase in le-vels of well-being. Through a longitudinal study, Recchi et al. (2020) evaluated subjective well-being in the French population using their index that combines the answers to six different questions about how often participants have felt nervous, depressed, relaxed, sad, happy, and lonely during the previous two-week period. The panel data covering the French population before and after the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic showed that self-reported well-being has improved during the lockdown compared to previous years; that is, subjective well-being scores have increased since the start of the lockdown. However, they found inequalities in subjective well-being; it was lower in the most financially vulnerable people and in those living in smaller households. They also found regional disparities: residents in Paris experienced a considerable and significant decrease in their subjective well-being score compared to the rest of the country.

Sibley et al. (2020), through a longitudinal study in New Zealand that began in October 2019 and continued during the pandemic, analyzing two indicators of subjective well-being, satisfaction with life (Diener et al., 1985) and loosely interpreted personal well-being-which implied satisfaction with living standards, future safety, personal relationships, and health (Cummins et al., 2003)-, found no decrease in subjective well-being at the beginning of the lockdown.

In our study, we also wished to explore the effect of the level of dispositional optimism, age, and gender, as possible moderating variables on the participants’ well-being values during the lockdown. The results showed a moderation effect of dispositional optimism on the Accomplishment domain during the lockdown (M2) in all the people, with the score in the Accomplishment domain increasing as participants started out with higher levels of optimism; that is, the more optimistic the person is, the more their score increases in the Accomplishment domain during the lockdown (M2). There was no moderation effect of dispositional optimism on any other well-being domains.

Regarding gender as a moderating variable, the results also showed a gender moderation effect during the lockdown (M2) only in the well-being domain Happiness. A different effect occurred in the two genders: in men, happiness increased during the M2 lockdown, compared to the first M1 measurement, when they were not yet confined, and in women, happiness decreased during the M2 lockdown, compared to the first M1 measurement.

Finally, the age of participants did not show a moderation effect on any of the well-being domains during the lockdown. We have not found any studies analyzing the moderating effect of these variables on well-being during the lockdown, so we cannot compare our results.

Several limitations of this study are worth mentioning. We applied self-report measures, so social desirability likely influenced the response to the tests. Another limitation of this study is the loss of participants in the second measurement due to the confinement situation. As, to date, no other longitudinal study has been carried out that jointly measures hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, it is difficult to genera-lize the results, especially given the various biases and cultu-ral diversities.

We do not know the exact causes that have led to the decrease in some of the well-being domains, however, there are several reasons why people’s life satisfaction may have decreased during the early stages of the COVID-19 pande-mic. Restrictive measures implemented to prevent the spread of the virus including quarantine, physical distancing, and isolation of infected and at-risk populations, and the people also experience more stress factors, such as health-related concerns, job insecurity, work-family conflicts and discrimination, may lead to increased feelings of uncertainty and loneliness (Zacher & Rudolph, 2021).

We can conclude that the lockdown has not affected well-being in its entirety but it has affected some of the assessed domains of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. The well-being that decreased during the lockdown refers to the Positive Emotion, Engagement, Meaning, and Overall Well-being (PERMA) domains, whereas the well-being referring to negative emotion increased. There is a moderation effect of dispositional optimism on the Accomplishment domain during the lockdown (M2), such that the more optimistic the person is, the more their accomplishment score increases during the lockdown. Gender also had a moderation effect on the happiness domain during the lockdown: in men, the Happiness score increased during the lockdown and, in women, it decreased, both genders compared to their previous levels of non-confinement.

This study is the first longitudinal study to provide evidence of how the domains of well-being have evolved, including the hedonic and eudaimonic aspects of well-being, evaluated before and during the lockdown in the Spanish population. It also provides evidence of the moderating effect of dispositional optimism and gender. These results can help us understand the general health status of the confined population that did not have COVID-19. The findings may also be useful to psychological practitioners, as they can suggest ways to cognitively frame pandemic crises and support individuals’ effective coping efforts to help improve well-being. These factors need to be addressed in future research and may also be useful in dealing with other potential future crises.