Introduction

Psychological research on the subject of happiness has seen an increase over the last three decades (Luhman et al., 2012; Van Hoorn, 2007). One reason for this recent interest is linked to the role that happiness and life satisfaction play in improving an individual's life quality (Diener, 2000; Medvedev & Landhuis, 2018; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Suh et al., 1998). The study of happiness has also been of interest since ancient times (Diener, etal 2009) and is particularly considered in Western culture as the ultimate goal in life, (Suh & Choi, 2018; Uysal et al., 2014; Veenhoven, 1994).

Historically, there are two different approaches to the concept of happiness. While the eudemonic perspective focuses on psychological well-being (human strengths and potential to reach optimal functioning; Ryff & Keyes, 1995), the hedonic perspective has more broadly defined happiness as subjective well-being (SWB), related to people´s assessment of their lives. SWB in particular, consists of an affective component (the prevalence of positive emotional experiences over negative ones; Diener, 2009) and a cognitive component (evaluation of one's life satisfaction; Diener, 2009). Although SWB and subjective happiness (i.e., a global, subjective assessment of whether one is happy or unhappy; Lyubomirsky, & Lepper, 1999) have a strong correlation and are often considered synonymous, some authors mention no overlap between either concept (Gallagher et al., 2009; Howell et al., 2010; Iani et al., 2013; Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999; Purvis et al., 2011). From this perspective, subjective happiness is not just a matter of a daily, positive mood or general satisfaction with life, but a more enduring and chronic state (Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2014).

In an extensive review of the connection between subjective happiness and health promotion, Scorsolini-Comin & Santos (2010) reported that the former is positively linked to a wide range of personal outcomes, such as academic performance (Dela Coleta & Dela Coleta, 2006), emotional support (Resende et al., 2009), or coping strategies (Shmotkin, 2005). Other variables traditionally related to SWB are emotional intelligence (Extremera et al., 2005), self-esteem (Furnham & Cheng, 2000; Shimai et al., 2004) satisfying relationships (Diener & Seligman, 2004) or personal control (Larsen & Prizmic, 2008). Indeed, extensive research highlighted the close links between happiness and both physical (Cross et al., 2018; Kushlev et al. 2020; Steptoe, 2018) and mental health (Lew et al., 2019; Lyubomirsky et al., 2005; Piqueras et al., 2011).

In this context, many researchers have attempted to understand the most relevant determinants in SWB or subjective happiness development. Among those described are internal factors such as personality attributes (Diener & Lucas, 1999; Moradi et al., 2005; Rusting & Larsen, 1997) or genetic disposition (Lykken & Tellegen, 1996; Roysamb & Nes, 2018); and external factors such as socio-demographic variables (Botha et al., 2017; Diener et al., 1999; Frey & Stutzer, 2002; Furnham & Petrides, 2003; Kasser & Kahner, 2004; Weech-Maldonado et al., 2017), life events (Ballas & Dorling, 2007; Clark & Oswald, 2002) or social contexts (Diener & Biswas-Diener, 2008); Holder & Coleman, 2009; North et al., 2008). Regarding the latter, family relations emerged as a critical variable in understanding subjective happiness, notably in early development stages.

In this line, connections between family functioning and SWB or subjective happiness in childhood and adolescence have been extensively documented in psychology literature. Thus, subjective happiness has been positively predicted from a wide range of family aspects, such as family cohesion (Fosco et al., 2020; Goswami, 2012; Hamama & Arazi, 2012; Leto et al., 2019; Xiang et al., 2020), positive family dynamics (Joronen &Astedt-Kurki, 2005; Rask et al., 2003) parental warmth (Kazarian et al., 2010) participation in family decisions (González et al., 2015), or family support (Hellfeldt et al., 2019; Rodriguez-Rivas et al., 2022); and negatively predicted by others, such as parental psychopathology (i.e., stress, anxiety or depression; Leto et al., 2019), family conflict (Fosco et al., 2020) or parental rejection (Kazarian et al., 2010). Although in early adulthood, family still plays a role in an individual's adjustment, particularly in cultures like the Spanish one where young people live with their parents well into their twenties, its connections with subjective happiness are less explored. These few studies have focused on the importance of family cohesion, support and involvement in young people´s SWB (Asici & Sari, 2021; Brannan et al., 2012; Schnettler et al., 2014; Xiang et al., 2020), however more research is required.

To understand the nature of the relationship between family and subjective happiness in early development stages, Bronfenbrenner's bioecological model provided a comprehensive, conceptual framework for how the central social contexts in an individual's life interact and influence adjustment (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006).

From this perspective, to ensure an individual´s optimal development, all participants in its microsystems should pursue effective interaction patterns called proximal processes (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). Nevertheless, the instability inherent in our society as regards family structure and functioning has had a profound, negative effect on the quality of these interactions. Specifically, the rise in divorce, amount of time parents spend away from home, and the strong irruption of digital technology in young people´s lives, among other factors, alter current family functioning patterns. Therefore, better understanding is required about which family patterns are functional and dysfunctional in early adulthood, since improved knowledge of all these aspects will contribute toward optimizing the quality of family interactions in young people and thus subjective happiness and life satisfaction.

The bioecological model also considered an individual's adjustment as a result not only of their social contexts, but also of their own personal characteristics (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). In this line, personality has proved strongly related to happiness in adulthood, with the more neurotic adults being those who show lower levels of happiness (Costa & McCrae, 1980; Furnham & Cheng, 2000; Hills & Argyle, 2001; Lauriola & Iani, 2015). However, on the basis that personality is still developing even past age 30 (Caspi & Silva, 1995;Costa & McCrae, 1994), temperament is widely considered a good measure of personality constructs in early development stages (Buss & Plomin, 1984; Holder & Klassen, 2010; Rothbart, 2007). In this connection, a study about adult temperament structure developed by Rothbart and Evans (2007) found that neuroticism was strongly related to the temperament scale of negative affect, considered as a high level temperamental motivational-emotional domain associated to potentially aversive stimuli. This association suggests that negative affect might be a temperament factor particularly relevant in explaining the contribution of individual characteristics to happiness and well-being. As with neuroticism, it might be expected that people with higher levels of negative affect could experience a more intense and negative response to environmental stressors, which consequently would decrease their levels of subjective well-being.

Although there is a great deal of research highlighting the relevant role of negative affect explaining several developmental outcomes (Clark et al., 1994; Crawford et al., 2011: Hirvonen et al., 2019; Rothbart et al., 1994), its relation to subjective well-being has been much less studied. Besides, this scarce literature has generally focused on single aspects of negative affect, such as shyness (Satici, 2019; Wang et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2012), which may offer a partial vision about the nature of this relationship. Once more, these few studies focused primarily on childhood and adolescence, putting emerging adulthood on a second level. Therefore, in actual practice, the link between young people's negative affect and happiness has barely been explored.

In addition to the single contributions of family functioning and negative affect, interaction between these factors is also of utmost importance. According to Rothbart's theory, temperament can be a protector or risk factor in the connection between different family subsystems and an individual's adjustment, playing a mediating or moderating role in this interplay (Garstein & Fagot, 2003). Several studies have confirmed the mediating or moderating role of temperament in the relationship between parenting and an individual's adjustment problems, mostly in childhood (Ato et al., 2015; Eisenberg et al., 2005; Karreman et al., 2008). Extrapolating this relationship pattern to early adult adjustment, it is to be expected that an individual's temperament can reduce or increase the impact of a dysfunctional family on their subjective well-being. We also believe that how family functioning affects negative emotionality expression may be conditioned by cultural beliefs about the family role in an individual's life. To our knowledge, this relational pattern has not yet been studied; thus its implications are not well understood.

Our main aim was to analyze the link between family functioning, negative affect and subjective happiness in a sample of young Spanish adults. Firstly, we expected family cohesion and flexibility to correlate with higher perceived well-being and for dysfunctional family interactions to correlate with lower happiness in young people. We also expected a negative correlation between negative affect and subjective happiness in early adulthood. Secondly, we examined the mediating role of negative affect in the relationship between family functioning and subjective happiness. In particular, we expected poor family functioning to increase the expression of negative affect in early adults, which in turn would decrease subjective happiness. We were also interested in finding which family dysfunctional patterns are worse for negative affect and subjective happiness in young people as regards Spanish culture. For our data collection, in the context of early adulthood we focused on college students, due to the emphasis this collective place on happiness, among other human values (Kim-Prieto et al., 2005).

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants were selected from the local university in Murcia, Spain. The goals of the research were explained and volunteers were requested. The original sample comprised 349 students enrolled in a four-year Educational college program (Primary Education, Infant Education and Social Education) at Murcia University (Spain). Two students were excluded due to generalized non-response to all items; the remaining students presenting a random pattern of 2 % missing responses imputed by the median of cases. Distributed by gender, 78 of respondents were male (22.48 %) and 269 female (77.52 %). The average age was 19.3 years with standard deviation of 3.71.

Following approval by the institutional ethics committee, informed consent was obtained from participants. Questionnaires were completed in the classroom, where students could consult researchers on any question. Participation was voluntary and no payment was provided.

Instruments

Temperament. The short form of the Adult Temperament Questionnaire (ATQ; Evans & Rothbart, 2007) was used to measure this subject. The short form version of ATQ includes 77 items on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = extremely untrue, 7 = extremely true), grouped into 13 scales and four dimensions (i.e., negative affect, effortful control, surgency/extraversion and orienting sensitivity). We used R lavaan package version 0.6.11 (Rosseel, 2012) to perform a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with MLR (Robust Maximum Likelihood) estimator to test the model of four factors for ATQ. Using conventional criteria (Hu & Bentler, 1998-99; Kline, 2016), we obtained a modest but satisfactory fit: CFI = .91, SRMR = .074 and RMSEA = .026 (90 % CI: .22-.28), p > .05. Measurement reliability of ATQ scale was obtained with R psych (Revelle, 2022) and R semTools (Jorgensen et al, 2022). Alpha reliability for the four temperamental factors of ATQ was between .65 and .80, and composite reliability ranged between .54 and .69.

For our research purpose, we only evaluated the Negative Affect construct, composed of 4 scales: (1) Fear: The negative affect related to anticipation or distress (7 items); (2) Sadness: Negative affect and lower mood and energy related to exposure to suffering, disappointment, and object loss (7 items); (3) Discomfort: Negative affect related to sensory qualities of stimulation, including sensitivity, rate or complexity or visual, auditory, smell/taste, and tactile stimulation (6 items), and; (4) Frustration: Negative Affect related to interruption of ongoing tasks or goal blocking (6 items). The reliability range for scales of the Negative Affect dimension was between .72 and .80 (Evans & Rothbart, 2007). We used R lavaan package version 0.6.11 (Rosseel, 2012) to perform a confirmatory factor analysis with estimator WLSMV shorthand for Diagonally Weighted Least Squares with robust standard errors and mean- and variance-adjusted Chi-square statistics, developed by Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017), to test the model of 4 factors for Negative Affect (NA) construct. Using conventional criteria (Hu & Bentler, 1998-99; Kline, 2016) we obtained a reasonable fit: RMSEA = .050; p = .474, SRMR = .056, CFI = .941 and TLI = .922. Measurement reliability of NA was obtained using R psych version 2.2.5 (Revelle, 2022) and R semTools (Jorgensen et al, 2022). Cronbach's Alpha was .78 and Omega total was .81 (Revelle & Condon, 2019). Alpha reliability for the four scales of NA ranged between .64 and .75.

Family functioning. To measure family functioning we administered the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale (FACES IV; Olson & Gorall, 2006), in its Spanish adaptation (Rivero et al., 2010). This scale was designed to assess family cohesion (i.e., family members´ emotional bonding; Olson, 2000) and flexibility (i.e., the amount of change in family leadership, role relationships and relationship rules of a couple or family system; Olson & Gorall, 2003) as suggested by the Circumplex Model of Marital and Family Systems (Olson, 2000), whose main hypothesis is that healthy families are more balanced while problematic families are more unbalanced. The Spanish version of the scale discarded some of the original 42 items, resulting in 24 items on a 7-point Likert Scale (1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree), divided into two delimited groups: two balanced scales (Cohesion and Flexibility) assessing the moderate and healthy regions of both dimensions, and four unbalanced scales (Enmeshed, Disengaged, Chaotic and Rigid) measuring the upper and lower extremes of Cohesion and Flexibility. The range of reliability for the Spanish adaptation of FACES IV balanced scales was between .65 and .77, and for unbalanced scales between .51 and .74.

A confirmatory factor analysis with MLR estimation achieved a reasonable fit to the model of six factors of FACES IV (Robust RMSEA = .038: 90% CI: .029-.048; SMSR = .054, CFI = .960, and TLI = .951). Alpha reliability ranged between .57 and .81 and composite reliability between .53 and .82. Due to our interest in separately studying functional and dysfunctional family interactions, we replicated the confirmatory factor analysis separating both balanced and unbalanced scales, also obtaining a reasonable fit with both balanced (RMSEA = .068; p = .100; SMSR = .035, CFI = .985, and TLI = .978) and unbalanced scales (RMSEA = .053; p = .340; SMSR

= .058, CFI = .963, and TLI = .953). For balanced scales, Alpha and Omega total ranged between .68 and .81. For unbalanced scales, Alpha and Omega total reliability was between .49 and .76.

Subjective Happiness. In assessing this subject, we used the Subjective Happiness Scale (Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999) in its Spanish version (Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2014). This scale includes 4 items on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = very unhappy, 7 = very happy), where participants either self-rate their global subjective happiness or compare themselves to others. The internal consistency coefficient for the Spanish version was .81.

We also performed a CFA with MLR estimation to test the one-factor model of the Subjective Happiness scale and obtained a reasonable fit: RMSEA = .061; (90 % CI: .00-.20), SRMR = .016, CFI = . 997, and TLI = .982. Alpha reliability was .79 and composite reliability .76.

Data analysis

Using R psych package version 2.2.5 (Revelle, 2022), we first calculated descriptive and polychoric correlation coefficients in order to analyze directionality of relationships between latent variables.

To test mediation hypotheses we used structural equation modeling (SEM) implemented in R lavaan (Rosseel, 2012) and R semTools (Jorgensen et al., 2022). Mediation models have often followed the causal step method proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986), though this has been criticized both for its low statistical power (McKinnon et al., 2004; Preacher & Hayes, 2004), and the assumption that all observed variables are measured without error. In spite of many recent advances (Hayes, 2013; Rucker et al., 2011), Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) has many advantages over traditional regression analysis with observed variables as it is designed to test measurement and structural models in a single step; allow observed and latent variables, multiple independent, mediators, moderators and outcome variables; and provides essential information relative to the fitted model (Kline, 2016). Thus, the causal relationships in a mediation process, the simultaneous nature of the indirect and direct effects, and the dual role of the mediator as both a cause for the outcome and an effect of an intervention can be more appropriately expressed using SEM models than regression analysis (Woody, 2011).

In the specification of our mediational models, we take four latent variables into account: (1) Negative Affect (NA), as a second order factor which includes Fear, Distress, Frustration and Sadness scales; (2) Family balanced scales (FBS), with Cohesion and Flexibility; (3) Family unbalanced scales (FUBS), including Enmeshed, Disengaged, Rigid and Chaotic scales; and (4) Subjective Happiness (SH).

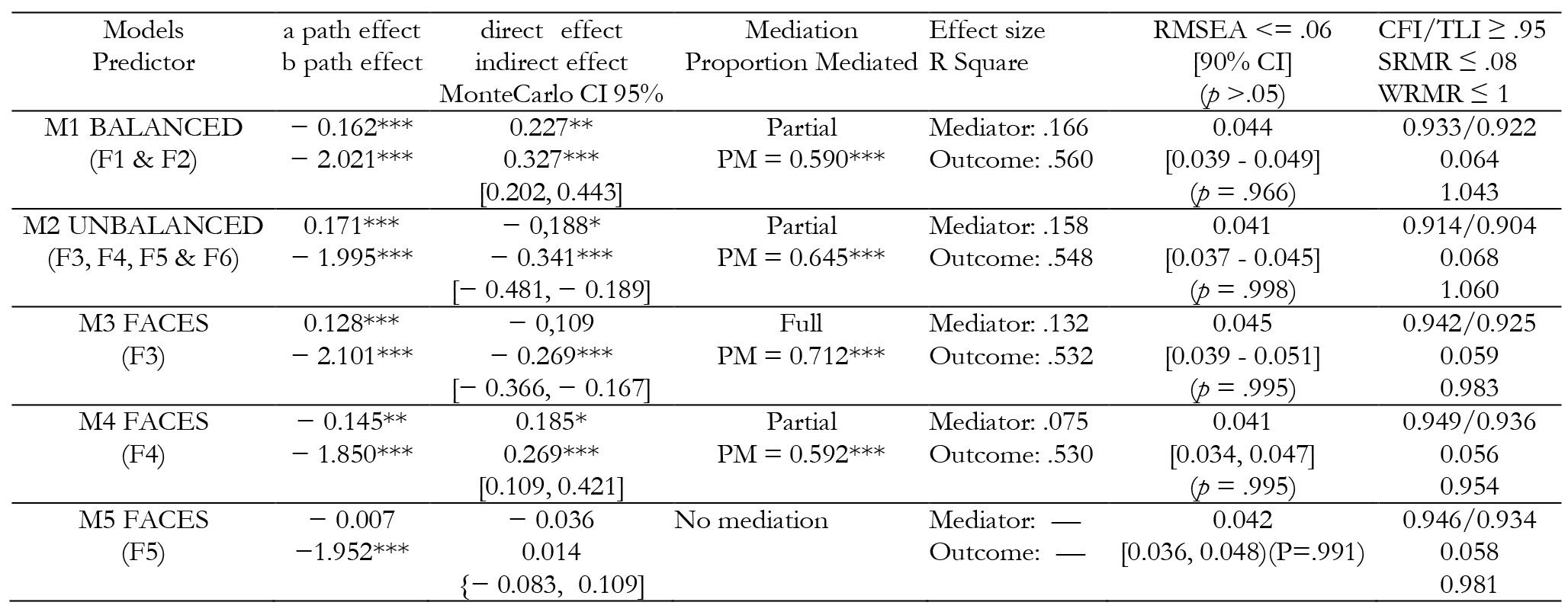

In a first step of our research planning, we use two SEM models to analyze the mediational pattern for both balanced and unbalanced family functioning: (M1) a model with FBS as predictor variable, SH as outcome variable and NA as the proposed mediator, and (M2) a model with FUBS as predictor variable, SH as outcome variable and NA as mediator.

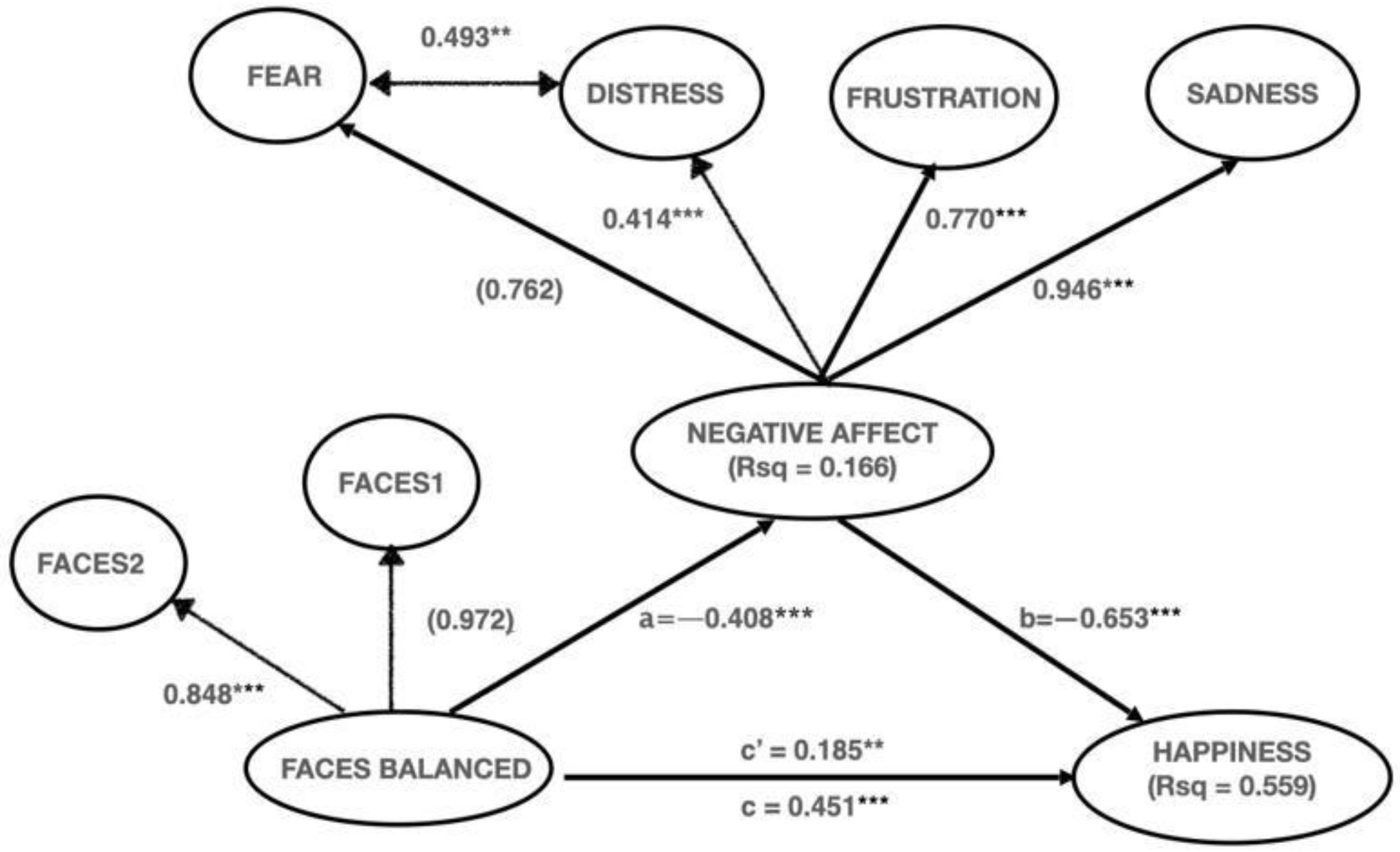

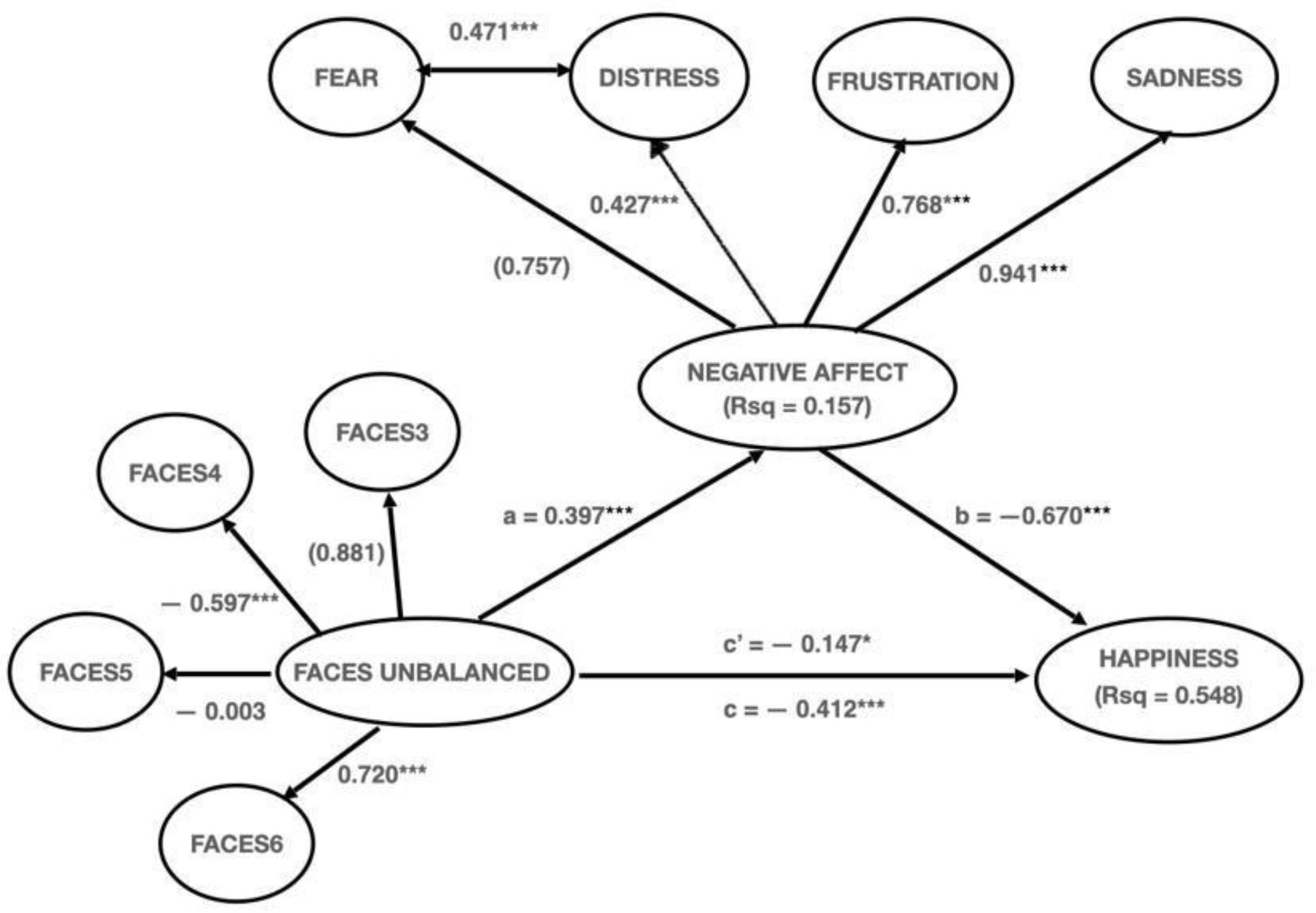

In a second step, we sought further knowledge on the role of different family dysfunctional patterns in this mediational structure. For that purpose, we tested new SEM, one for each unbalanced family scale as a predictor, and maintained SH as the outcome variable and NA as the proposed mediator. This led to testing four new mediational models: (M3) one with Disengaged scale (DS) as predictor, (M4) one with Enmeshed scale (ES), (M5) a model with Rigid scale (RS) and (M6), a model with Chaotic scale (CS) as predictor variable.

Due to the ordinal nature of our observed variables (Likert scales with 5 and 7 response options and a few items with skewness > 2 or kurtosis > 7), in all analyses we used WLSMV (Diagonally Weighted Least Squares with robust standard errors and mean and variance adjusted test statistic, as defined in Asparouhov & Muthén, 2010, and recommended by Finney & DiStefano, 2013, DiStefano & Morgan, 2014, and Shi et al., 2018). With semTools R package we also tested the indirect effect of all models with a robust MonteCarlo 95% confidence interval based on empirical sampling distributions of estimated model parameters (McKinnon et al., 2004; Preacher & Selig, 2012; Williams & McKinnon, 2008). To obtain an empirical distribution of indirect effects we drew 30,000 samples to minimize Monte Carlo error of the estimated CIs.

In order to select fit measures helping to evaluate the models tested, we followed some suggestions on differences from DWLS estimation compared to ML estimation (Savalei & Rhemtulla, 2013; Shi & Maydeu-Olivares, 2020; Xia & Yang, 2019), finally using the robust fit measures provided in the Lavaan version of DWLS. Following Hu and Bentler (1998-99), Kenny (2020), Kline (2016) and Hooper et al., (2008), we reported the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), with 90% CI and its P-value (minimum value for an acceptable fit: .06 and p >.05), the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR, minimum value for an acceptable fit: 0.08), the Weighted Root Mean square Residual (WRMR, optimal value approximately equal to 1), and standard fitting measures as the Comparative Fit Index (CFI ≥ .95) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI ≥ .95). We also added the Weighted Root Mean Square Residual Index (WRMR, with optimal value approximatively equal to or less than 1), first proposed by Muthén & Muthén (1998-2017), as it was specifically developed for categorical data and seems appropriate to detect misspecification of models (DiStefano et al., 2018; Yu, 2002). In other respects, we followed many recommendations on the best practices of reporting mediational analyses with SEM (González & McKinnon, 2021; Fairchild & McDaniel, 2017; Lachowich & Preacher, 2018), including the use of effect size measures (de Heus, 2012), unstandardized parameters (Greenland et al., 1991, however we inserted standardized coefficients in figures) and the Proportion of Mediation (PM), one which reflects how much of the predictor's effect on the outcome variable is due to its effect on the mediator (Ditlevsen et al., 2005; Nevo, et al., 2018, VanderWeele, 2013).

In all analyses, we considered a mediation hypothesis as complete or full if P (indirect effect) < .01 and P (direct effect) > .05, as partial if p (indirect effect) < .01 and P (direct effect) < .05. No mediation hypothesis was considered when P (indirect effect) > .05.

Results

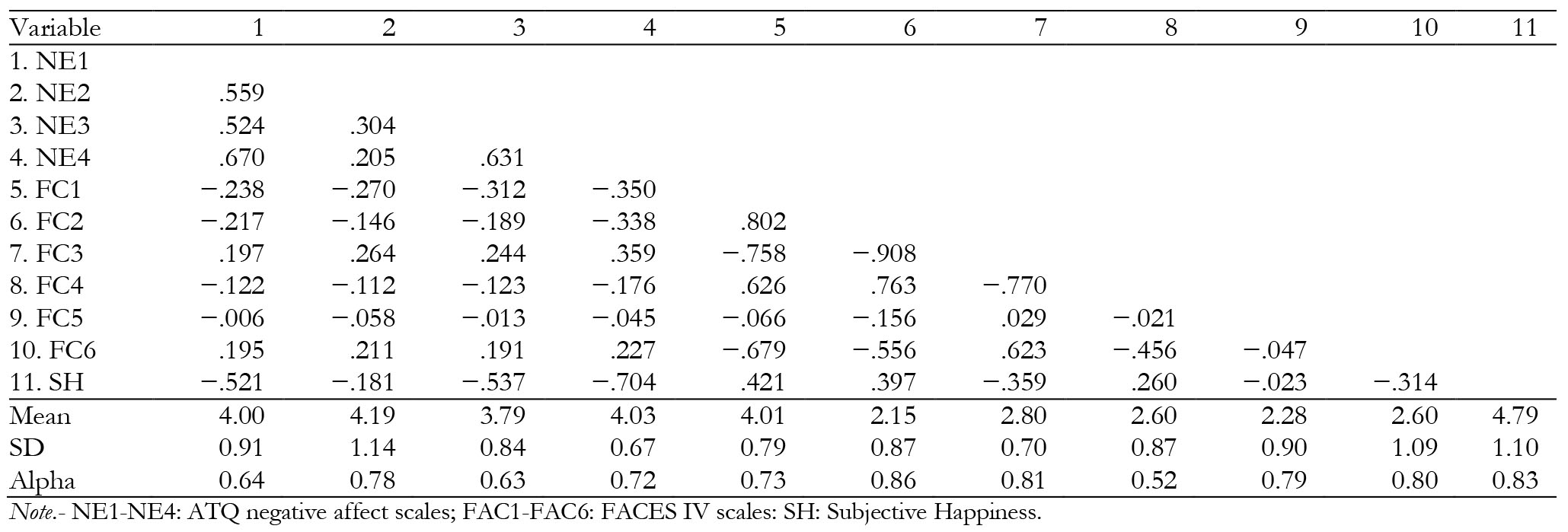

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics, reliabilities and polychoric correlation coefficients for all latent variables in our study (Gadermann et al., 2012). Examination of the correlation matrix revealed that NA subscales (i.e., Fear, Distress, Frustration and Sadness) positively correlated with Disengaged and Chaotic scales, negatively related with both FBS (i.e., Cohesion and Flexibility), and showed no correlation with Rigid scale. Both Frustration and Sadness negatively correlated with the Enmeshed scale.

Table 1: Means, standard deviations, ordinal reliabilities and intercorrelations between latent variables.

Note.NE1-NE4: ATQ negative affect scales; FAC1-FAC6: FACES IV scales: SH: Subjective Happiness.

Correlations between the four NA scales (i.e., Fear, Distress, Frustration and Sadness) and SH were negative. FBS scales and Enmeshed scale were positively correlated with SH, while Disengaged and Chaotic scales showed the opposite pattern. Ordinal Alpha coefficients of latent variables were modest with a range between .57 and .86.

The M1 model posited that Cohesion and Flexibility would predict SH over its effects on NA (see Table 2 for unstandardized and Figure 1 for standardized parameters). This model yielded satisfactory fit indices (SRMR = .064; WRMR = 1.043; RMSEA = .044; p = .966, CFI = .933 and TLI = .922) and a partial mediation hypothesis was confirmed. The indirect effect was .327; p < .001 and direct effect was .227; p < .01. Therefore, negative affect significantly mediates the relationship between family Cohesion/Flexibility and Subjective Happiness. Overall, the proportion of the effect of FBS on SH mediated by NE was 0.590.

Table 2: Mediation effects models and SEM fitting measures of FACES scales on SUBJECTIVE HAPPINESS mediated by NEGATIVE AFFECT.

Figure 1. SEM mediational model (M1) between FACES balanced scales (FBS; Cohesion and Flexibility), Negative Affect construct (NA; Fear, Distress, Frustration and Sadness) and Subjective Happiness (SH).

In order to assess how important NA was in accounting for the effect of FUBS on SH mediated by NE, another mediation model was tested (M2). Fit indices of this model were modest but reasonable (SMRM = .068; WRMR = 1.060; RMSEA = .041; p = .998, CFI = .914 and TLI = .904), and a partial mediation hypothesis was again confirmed (indirect effect: - .341; p < .001 and direct effect: - .188; p < .05), implying that dysfunctional family patterns significantly decreased young people´s Subjective Happiness by increasing Negative Affect. The proportion of mediated effect in this model was .645.

Figure 2. SEM mediational model (M2) between FACES unbalanced scales (FUBS; Enmeshed, Disengaged, Rigid and Chaotic), Negative Affect construct (NA; Fear, Distress, Frustration and Sadness) and Subjective Happiness (SH).

On confirming the mediating role of NA in the relationship between FUBS and SH, we were interested in analyzing possible differences between different unbalanced scales in this mediation pattern. Therefore, we tested four new SEM models, where M3 (indirect effect = - .269; p < .001; direct effect = - .109; p > .05) and M6 (indirect effect = -.178; p < .01; direct effect = -.100; p > .05) presented full mediation, M4 (indirect effect = .269; p < .001; direct effect = .185; p < .05) presented partial mediation and the M5 model, as expected, presented no mediation. The proportion of mediation of SH represented by the NA was .712 for M3, .592 for M4 and .641 for M6. Fit indices of these models were also modest but satisfactory for M3 (SMRM = .059; RMSEA = .045; p = .995, with CFI = .942, TLI = .925 and WRMR = .983), M4 (SMRM = .056; RMSEA = .041; p = .995, with CFI = .949, TLI = .936 and WRMR = .954) and M6 (SMRM = .057; RMSEA = .043; p = .977, with CFI = .947, TLI = .933 and WRMR = 1.003). Thus, Disengaged and Chaotic family functioning can potentially predict a decrease in Subjective Happiness increasing young people´s Negative Affect, while Enmeshed family functioning may predict an increase in perceived happiness decreasing Negative Affect.

Finally, in order to determine whether there were differences in this mediation pattern regarding gender, we tested mediation models with multiple group SEM and found that in model 4 only females and not males, presented this mediation pattern (diff= -.398, 95% CI [-.965/-.048] and p < .01). Although no differences were found for the rest of models, we believe this result deserves to be explored in future research with a greater sample size (particularly males).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyze the connection between family functioning, negative affect and subjective happiness in a sample of Spanish college students. Specifically, we sought to analyze the impact of family functioning and negative affect on subjective happiness in early adulthood and clarify the potential mediating role of negative affect in the relationship between family functioning and subjective happiness. In this mediational context, we also tried to compare different dysfunctional patterns to understand which are more negative in terms of young people's negative affect and subjective happiness in Spanish culture.

Regarding the first aim, our results show moderate levels of family cohesion and flexibility correlated positively with the student's subjective happiness, while some extreme levels of both scales (i.e., Disengaged and Chaotic), showed the opposite pattern. Although scarce, other studies have highlighted the importance of effective family functioning in an individual´s perceived happiness in early adulthood (Asici & Sari, 2021; Brannan et al., 2012; Schnettler et al., 2014, Xiang et al., 2020). From the bioecological model, an individual´s behaviors and well-being are explained by the direct influence of microsystems, family being one of the most relevant for an individual's development. On the basis that life satisfaction is strongly influenced by the degree of success in areas that individual value more (Oishi et al., 1999), the family´s role in an individual's happiness would be strongly conditioned by cultural beliefs. Spanish culture is traditionally family oriented (Jurado & Naldini, 1996), highlighting the role a family microsystem plays in explaining an individual's well- being. From the circumplex model (Olson et al., 2000), both cohesion and flexibility are considered curvilinear variables, indicating that both extremes are dysfunctional and correlate with more relationship problems, while moderate levels are not (Rivero et al., 2010). However, our correlation analyses led us to a contradictory result according to the Circumplex model, revealing a positive correlation between enmeshed family behaviors and young people's subjective happiness. As explained below, we believe this striking result may be related to Spanish family idiosyncrasies.

As for student temperament, we found that higher levels of negative affect correlate with lower levels of perceived happiness. There is abundant literature supporting positive correlations between negative affect and a variety of negative outcomes, particularly in childhood and adolescence (Eisenberg et al., 2005; Laible et al., 2010; Moran et al., 2013; Shewark et al., 2021). One possible explanation is that more negatively reactive children seem to be affected in social and emotional skills, raising the likelihood of exhibiting a wide range of psychological disorders. In relation to our research aim, the impact of negative affect on positive adjustment in early adulthood has been little explored in the literature, although it is assumed that the same implicit mechanisms described in previous stages are involved.

Results of mediation analyzes including both balanced and unbalanced FACES scales confirmed the mediational role of negative affect in the relationship between family functioning and subjective happiness, both models showing full mediation. In other words, students who live in “healthier” families seem to experience fewer levels of negative emotions, which improve their social and emotional satisfaction and perceived happiness. In contrast, those living in families with dysfunctional patterns experience higher levels of negative emotions and lower levels of subjective happiness. The mediating role of temperament in the relationship between family functioning and an individual's adjustment has been previously studied in childhood and adolescence (Ato et al., 2015; Eisenberg et al., 2005; Karreman et al., 2008), however, as far as we are aware, not regarding positive adjustment in early adulthood. From the bioecological perspective, interactions between individual characteristics and the influence of social context in the explanation of individual adjustment may help in understanding our mediational model. In this respect, our data results lead us to believe that family functioning has no direct effect on young people's perceived happiness, but an indirect effect through its role in modulating the expression of negative emotions such as anger, frustration and sadness. Family functioning has an amplifying or mitigating effect on young people's negative affect, directly influencing satisfaction and happiness.

On the subject of “less well-adjusted families”, we tried to study different dysfunctional patterns allowing us to clarify which have higher impact on young people's negative affect and subjective happiness, in the context of Spanish culture. With this goal in mind, we replicated our mediational model separating the different unbalanced scales of family functioning, obtaining a significant result for Disengaged, Enmeshed and Chaotic scales, but not for the Rigid scale. However, we found that though Disengaged and Chaotic scales had a positive relationship with Negative Affect construct, Enmeshed scale had a negative one. Thus, it appears that students living in families which are extremely disengaged or chaotic are at higher risk of expressing intense negative emotions, and so experience lower perceived well-being. Unexpectedly, families showing more enmeshed or dependent behaviors seemed to mitigate children's negative affect and thus there was increased perceived happiness. Despite negative relations between disengaged, enmeshed or chaotic family functioning and subjective happiness being previously reported in the literature (Gao & Potwarka, 2021; Manzi, et al., 2006; Szczesniak &Tulecka; 2020), there are no studies that have approached this relationship and explored the mediating role of negative affect.

A plausible explanation for these results may be provided by Spanish beliefs on parenting and family functioning. In this regard, compared to others, Spanish culture is traditionally family oriented, and places great emphasis on cohesion between family members. Most European countries show individualistic tendencies, however Spain maintains significant collectivistic features, particularly in family issues. It is perhaps for this reason that unbalanced cohesion functioning showed a significant impact on students´ negative affect and ulterior subjective happiness, because this aspect is particularly relevant in our culture. Besides, due to the intense expression of affection associated with the Spanish character, and its family orientation, it is not surprising that Spanish students may interpret enmeshed and dependent family behaviors as a normal expression of family cohesion and love. Furthermore, the transition to early adulthood in Spain does not presuppose separation from the family origin, unlike other European countries. This can explain why enmeshed behaviors can be seen as positive in Spanish culture, where young people's identity is not linked to a separation from family, while the opposite pattern has been reported in other countries (Manzi et al., 2006). On the contrary, disengaged family interactions may be perceived by young Spanish people as lack of love and a sign that something is not working in their families, which may increase their negative affect and subsequently decrease subjective happiness.

With regard to extreme flexibility scales, chaotic family functioning appears to have a negative impact on student's temperament, and ulterior subjective happiness. This is an expected result that might be accentuated in Spanish culture and explained by the fact that emerging adults still live with parents. It seems logical that they benefit more from organized and structured environments than emerging adults who live apart from parents. Additionally, chaos may be interpreted by young Spanish people as a signal of disinterest and disengagement, which is negatively perceived by Spanish families. As a result of this cultural perspective, we understand that students who live in disengaged and chaotic family environments appear to be at higher risk of experiencing negative emotions, which in turn may affect their perceptions of happiness and well-being, but not students who live in enmeshed environments, usually understood in our culture as normal or even positive.

In conclusion, we believe that important issues arise from the findings of our study leading to a number of social and clinical considerations. It is necessary that clinical interventions work in parallel with individual dispositions and family functioning in the search for greater levels of well-being in emerging adults. Since high levels of negative emotions such as anger or sadness, appear to decrease young people´s life satisfaction, it is important to teach strategies that improve their self-regulation skills and provide them with higher control of emotional reactivity. Young people´s clinical interventions must involve their parents, providing awareness on how unbalanced family functioning influences their children´s negative affect and ulterior happiness, and helping them to develop adequate cohesion and flexibility behaviors. Likewise, parents should know which dysfunctional patterns amplify their children's negative emotions according to cultural values, and what this entails for young people's subjective happiness. What emerges from our study is that Spanish parents should be particularly vigilant toward disengaged and chaotic patterns of family functioning, as these pose an increased risk regarding negative affect and subjective happiness in college students.

Lastly, although we believe our research provides interesting new information on the interactive relationship between family and temperament and its influence on young people´s subjective happiness, it has some limitations that should be addressed in future research. One is its cross-sectional nature, which obliges us to be very cautious with the causal interpretation of results (Antonakis et al., 2010). In our model we assumed that family functioning has a potential causal effect on young people's negative affect, directionality replicated in previous research on how parents shape children's temperamental characteristics (Acker & O´Leary, 1996; Davidov & Grusec, 2006; Malatesta & Haviland, 1986). However, a longitudinal design would be much more appropriate in determining the directionality of this relationship. As for measurements in our study, data was gathered only through self-report, implying reporting bias. To overcome this limitation, multiple methods (i.e., parents report, laboratory measures, etc.) might be used in future research. Indeed, other temperament measures, such as effortful control or extraversion, should be relied on for better understanding of how temperamental characteristics affect young people´s well-being. Finally, we have worked with a sample which is not representative; therefore, our results couldn´t be extrapolated apart from Spanish college students. In this line, it would be desirable not only to use a more representative sample, but also use data from several countries, allowing more precise analyses on how cultural values intervene in the relationship between family functioning, temperament and subjective happiness.