Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Gaceta Sanitaria

versão impressa ISSN 0213-9111

Gac Sanit vol.27 no.6 Barcelona Nov./Dez. 2013

https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2013.03.001

Intimate partner violence in Europe: design and methods of a multinational study

La violencia de pareja en Europa: diseño y métodos de un estudio multinacional

Diogo Costaa,b, Joaquim J.F. Soaresc,d, Jutta Linderte,f, Eleni Hatzidimitriadoug, Andreas Karlssoh, Örjan Sundinh, Olga Tothi, Ellisabeth Ioannidi-Kapolouj, Olivier Degommek, Jorge Cervillal, Henrique Barrosa,b

aDepartment of Clinical Epidemiology, Predictive Medicine and Public Health, University of Porto Medical School, Porto, Portugal

bInstitute of Public Health, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

cDepartment of Public Health Sciences, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden

dInstitution for Health Sciences, Department of Public Health Sciences, Mid Sweden University, Sundsvall, Sweden

eDepartment of Public Health, Protestant University of Applied Sciences Ludwigsburg, Ludwigsburg, Germany

fDepartment for Medical Psychology and Medical Sociology, University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany

gFaculty of Health and Social Care Sciences, Kingston University and St George's, University of London, London, United Kingdom

hDivision of Psychology, Department of Social Sciences, Mid Sweden University, Östersund, Sweden

iInstitute of Sociology, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest, Hungary

jDepartment of Sociology, National School of Public Health Athens, Athens, Greece

kInternational Centre for Reproductive Health (ICRH), Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

lDepartmental Section of Psychiatry and Psychological Medicine, University of Granada, Granada, Spain

This research was financially supported by the Executive Agency for Health and Consumers-European Commission [contract: 20081310].

ABSTRACT

Objective: To describe the design, methods, procedures and characteristics of the population involved in a study designed to compare Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) in eight European countries.

Methods: Women and men aged 18-65, living in Ghent-Belgium (n = 245), Stuttgart-Germany (n = 546), Athens-Greece (n = 548), Budapest-Hungary (n = 604), Porto-Portugal (n = 635), Granada-Spain (n = 138), Östersund-Sweden (n = 592), London-United Kingdom (n = 571), were sampled and administered a common questionnaire. Chi-square goodness of fit and five-age strata population fractions ratios for sex and education were computed to evaluate samples" representativeness.

Results: Differences in the age distributions were found among women from Sweden and Portugal and among men from Belgium, Hungary, Portugal and Sweden. Over-recruitment of more educated respondents was noted in all sites.

Conclusion: The use of a common research protocol with the same structured questionnaire is likely to provide accurate estimates of the general population IPV frequency, despite limitations in probabilistic sampling and restrictions in methods of administration.

Key words: Intimate partner violence. Methods. Multi-centre study. Men. Women. Europe.

RESUMEN

Objetivo: Describir el diseño, los métodos, los procedimientos y las características de la población participante en un estudio diseñado para comparar la violencia de la pareja íntima en ocho países.

Método: Formaron parte de la muestra mujeres y hombres (18-65 años de edad), residentes en Ghent-Bélgica (n= 245), Stuttgart-Alemania (n = 546), Atenas-Grecia (n = 548), Budapest-Hungría (n = 604), Porto-Portugal (n = 635), Granada-España (n = 138), Östersund-Suecia (n = 592) y Londres-Reino Unido (UK) (n = 571). Se les administró un cuestionario común. Se calcularon la prueba de ji al cuadrado de bondad de ajuste y razones de fracciones poblacionales de cinco estratos de edad, según sexo y nivel educativo, con la finalidad de evaluar su representatividad.

Resultados: Se encontraron diferencias en las distribuciones de edad en las mujeres de Suecia y Portugal, y en los hombres de Bélgica, Hungría, Portugal y Suecia. Ha habido un exceso de reclutamiento de encuestados con un nivel educativo más alto en todos los países.

Conclusiones: Un protocolo común de investigación con el mismo cuestionario estructurado puede proporcionar estimaciones precisas de la frecuencia de violencia de la pareja íntima en la población general, a pesar de las limitaciones existentes en la creación de muestras probabilísticas y en los métodos de administración.

Palabras clave: Violencia infligida por la pareja. Métodos. Estudio multicéntrico. Hombres. Mujeres. Europa.

Introduction

In Europe, there is no comprehensive investigation designed to estimate the size and impact of intimate partner violence (IPV) on the health status of adult men and women residing in different countries, applying common standardized measurement methods and assessing both victimisation and perpetration.

To address such gaps, we designed a cross-sectional community study aiming to estimate IPV prevalence, identify its determinants and health consequences, based on samples of adult men and women from eight European countries.

The current paper presents and discusses the design and methods of the DOVE project (Domestic Violence against Men/Women in Europe) and describes the study population characteristics in the participating centres.

Methods

Population

We targeted the general population aged 18-65 living in eight cities: Ghent-Belgium; Stuttgart-Germany; Athens-Greece; Budapest-Hungary; Porto-Portugal; Granada-Spain; Östersund-Sweden; London-United Kingdom (UK). Assuming an expected IPV prevalence of 15%1 and 3.0% of relative precision, size of samples was determined as 544 (272 women) for each centre. Samples were proportionally stratified according to age and sex, based on national Statistics Institutes data for resident population in 2008. Non-institutionalized national citizens or documented migrants residing in the participating cities were eligible.

Sampling procedures

Registry-based sampling was used in Spain, Belgium, Germany and Sweden and random-route was used in Greece and Hungary. In Portugal, two strategies were used: registry-based sampling and random-digit-dialling. The UK also resorted to two sampling strategies: registry-based and a via-public approach.

Participants selected through registries were sent an invitation letter with a project summary. Data collection took approximately 9 months and was completed in May 2011.

Random sample lists were obtained through city's municipality registries in Belgium (n = 2720), Spain (n = 2176) and Germany (n = 3077), through electoral registry in Portugal (n = 1990) and UK (n = 4720) and through state person address registry in Sweden (n = 1996).

Additionally, in Porto we used random-digit dialling of Porto city landlines (n = 10623 calls) and in the UK participants were approached in public settings (n = 1280).

In Belgium, Portugal and Germany, after sending invitation letters, participants were called to schedule an interview. In Greece, random route sampling was based on stratification of four major regions of the Greater Municipality Area of Athens according to geographical proximity of municipalities and similar socioeconomic structure. In Hungary, streets were selected from localities in Budapest. An adapted Leslie Kish Key was used for participant selection.

Assessment tool

The assessment tool comprised a range of existing validated scales and questions designed specifically for this study. It included information on socio-demographics, intimate relationships, physical and mental health, use of medication, past-year health care use. The following scales were included: WHO-AUDIT - Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test,2 Short Form (SF-36) Health-Related Quality of Life Questionnaire,3 Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),4 Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS),5 and Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms Scale.6 IPV was assessed with the Revised-Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2),7 and violence-associated factors were examined with the Controlling Behaviours Scale-Revised8 and seven items assessing exposure to child abuse.

The tool was piloted using convenience samples in each city (n = 89 total pilot sample) and the study protocol was approved by local Research Ethics Committees.

Method of administration

Questionnaires were administered by face-to-face interviewing for all sections, except for the IPV sections, which was self-administered for ethical reasons. As a last alternative option, questionnaires could be mailed in all countries if participants were otherwise unreachable. The only variation of administration occurred in Sweden, where questionnaires were posted to identified participants with a pre-paid envelope for return as per this ethics committee's request.

The WHO ethical and safety guidelines9 for the conduct of this type of research were considered by all centres and a study manual was produced in accordance. Interviewer training included presentation of the projects" aims, detailed explanation of survey tool, role-playing involving scenarios related to introducing the interview, dealing with difficult participants and sensitive situations, research ethics and safety during field work including handling of reported/witnessed IPV incidents and a crisis-intervention protocol. The voluntary character of participation was emphasized and, although written informed consent was obtained by all face-to-face interviewed participants, no link between signed consents and questionnaires existed.

Necessary steps were taken by interviewers to ensure that the interview took place in a confidential and safe manner, meaning that only the trained interviewer and interviewee were present in the private setting during the completion of the questionnaire. In case a third person was present and refused to leave, the interviewer would have explained that, according with the study's objectives, he/she could not carry out the interview and would have tried to re-schedule it to another day and/or place. Questionnaires were administered at participants" home (Greece, Hungary), university premises (Belgium) or either places (Portugal, Germany). In the UK, university premises and pre-selected public locations (with private spaces) were used.

Statistical analysis

To assess national samples representativeness, chi-square goodness of fit tests were used to compare the proportions of participants with each city population. Also, Population Fractions (PFs) by age and sex were computed for each country, using the corresponding reference city population provided by the national statistics institutions for 2008. PF was defined as the number of persons responding in each age-sex group divided by the number of persons with the same characteristics according to the available data. Population fraction ratios (PFRs, ratio of men" to women" PF) were estimated for each country. PFRs greater than 1 indicate an “excess” of men in the sample, while an excess of women is indicated by PFRs lower than 1.

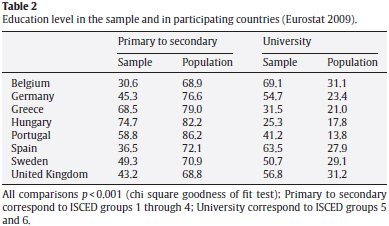

Participants" educational level was categorized to match International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) into two categories: primary to secondary corresponding to ISCED levels 0-4 (pre-primary, primary, basic, secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education), and university corresponding to ISCED levels 5 to 6 (tertiary). These were compared with the corresponding reference country population as available in Eurostat10 for 2009. PFs by age and education were computed for each country, so as PFRs for education. An “excess” of participants with education level university is indicated by PFRs lower than 1, compared to the country's distribution in that age strata.

A within-country comparison of the resulting samples according to age, sex and education was conducted for Portugal and UK. Chi square tests and Student's t-tests were used when appropriate. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 18 was used.

Results and discussion

Across study sites, more women than men participated in the study (Table 1, and see Table I in online Appendix) and a slightly higher proportion of older women participated compared to the city populations. Significant differences in the age distributions were found among women from Sweden and Portugal and among men from Belgium, Hungary, Portugal and Sweden (Table 1).

This may be expected, since Europe is currently facing a general demographic decline with the ageing of part of its population. We also interviewed proportionally more university-educated people than expected (Table 2, and see Table II in online Appendix). However, the comparison we have presented is based on available data from Eurostat for 2009, referring to whole country populations and not specifically the urban centres sampled. This could explain why the education level of participants is higher than the national educational level for the age and gender groups analysed.

In Spain and Belgium, logistical and ethical constraints made it impossible to reach the target sample size in due time compromising the statistical power for drawing inferences when considering these samples. In particular, the Spanish team experienced significant delays obtaining census registries from the Spanish National Statistics Institute and recruiting participants due to public reluctance to discuss about domestic violence after important media exposure. In Belgium, the fieldwork was constrained by the fact that the ethics committee allowed only for interviews to be conducted in the university facilities and did not approve telephone or postal interviews, which resulted in poor recruitment rates. Nevertheless, the probabilistic sampling approach, based on total number of residents from each urban centre, was expected to allow reasonable approximations to the cities" demographic characteristics.

We were not able to evaluate correct cooperation and response rates in our samples, since information on refusals was not collected and, in some cases, it was even impossible to obtain due to the sampling procedures. However, a comparison of characteristics of participants sampled from different sources, within the same country, was conducted for the Portuguese and UK samples which adopted this approach (the remaining countries used only one sampling frame to identify participants: Greece and Hungary by random route, Sweden, Spain, Germany and Belgium through municipal or state person registries). Results from this comparison confirmed that, despite minor differences (more men and younger participants recruited via public vs. electoral registry), no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of any type of violence was found (results not shown). Therefore, it can reasonably be assumed that participants" characteristics were similar, independently of the sampling method used.

Overall it is noted that the cross-country design of the study as well as its sensitive topic raised a number of challenges of the project teams during the recruitment of participants and conduct of the fieldwork, which was completed with some minor time difference between sites. Nonetheless, the use of a common research protocol and survey tool has assisted in providing comparable prevalence estimates of IPV in men and women across the project centres.

Authors´ contributions

D. Costa, J. Soares, J. Lindert, E. Hatzidimitriadou, O. Sundin, O. Toth, E. Ioannidi-Kapolou and H. Barros conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination. D. Costa performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors critical reviewed the manuscript providing important intellectual contributions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgment

A PhD grant from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia [SFRH/BD/66388/2009] to DC is acknowledged.

Appendix. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2013.03.001.

References

1. Breiding MJ, Black MC, Ryan GW. Prevalence and risk factors of intimate partner violence in eighteen U.S. states/territories, 2005. Am J Prev Med. 2008; 34:112-8. [ Links ]

2. Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, et al. AUDIT: the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Guidelines for use in primary care. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [ Links ]

3. Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992; 30:473-83. [ Links ]

4. Zigmond A, Snaith R. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983; 7:361-70. [ Links ]

5. Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, et al. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988; 52:30-41. [ Links ]

6. Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, et al. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 1993; 6:459-73. [ Links ]

7. Straus MA, Hamby SL, Warren WL. The Conflict Tactics Scales handbook. Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2). CTS: Parent-Child Version (CTSPC). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 2003. [ Links ]

8. Graham-Kevan N, Archer J. Investigating three explanations of women's relationship aggression. Psychol Women Q. 2005; 29:270-7. [ Links ]

9. Ellsberg M, Heise L, Pena R, et al. Researching domestic violence against women: methodological and ethical considerations. Stud Fam Plann. 2001; 32:1-16. [ Links ]

10. Eurostat: your key to European statistics (Internet). European Commission. (Consulted on 17.11.2011). Available at: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/eurostat/home/. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

dmcosta@med.up.pt

(D. Costa).

Received 12 December 2012

Accepted 15 March 2013