Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Clínica y Salud

versão On-line ISSN 2174-0550versão impressa ISSN 1130-5274

Clínica y Salud vol.26 no.2 Madrid Jul. 2015

https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clysa.2015.06.001

Verbal expressions used by anaclitic and introjective patients with depressive symptomatology: Analysis of change and stuck episodes within therapeutic sessions

Expresiones verbales usadas por pacientes anaclíticas e introyectivas con sintomatología depresiva: análisis de episodios de cambio y estancamiento durante las sesiones terapéuticas

Nelson Valdés y Mariane Krause

Escuela de Psicología, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

The research reported in this paper was financed by the National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development [Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (FONDECYT)], Project No3130367: "Characteristics of the verbal expressions used by anaclitic and introjective patients with depressive symptoms during the therapeutic conversation and its relationship with therapeutic change".

ABSTRACT

A person's speech makes it possible to identify significant indicators which reflect certain characteristics of his/her personality organization, but also can vary depending on the relevance of specific moments of the session and the symptoms type. The present study analyzed 10 completed and successful therapeutic processes using a mixed methodology. The therapies were video-and audio-taped, as well as observed through a one-way mirror by trained observers. All the sessions of each therapy were considered (N = 230) in order to identify, delimit, transcribe, and analyze Change Episodes (CEs = 24) and Stuck Episodes (SEs = 26). Each episode was made up by patients' speech segments (N = 1,282), which were considered as the sampling unit. The Therapeutic Activity Coding System (TACS-1.0) was used to manually code each patient's verbalizations, nested within episodes and individuals, in order to analyze them using Hierarchical Linear Modelling (HLM). The findings suggest that anaclitic patients tend to use more verbalizations in order to ask for feedback or to be understood by their therapists (attune), whereas introjective patients tend to use more verbalizations in order to construct new meanings (resignify) during therapeutic conversation, but especially during SEs. Clinical implications to enrich the therapeutic practice are discussed.

Key words: Change episode. Therapeutic dialogue. Communicative actions. Communicative patterns. Personality organization.

RESUMEN

La manera como una persona habla permite dar cuenta de ciertos indicadores que reflejan características de su organización de personalidad, pero además estos pueden variar dependiendo de la relevancia de momentos específicos de la sesión y de la sintomatología de las pacientes. El presente estudio analizó 10 procesos terapéuticos completes y exitosos utilizando una metodología mixta. Todas las terapias fueron grabadas en audio y video, además de ser observadas por observadores entrenados a través de un espejo de visión unidireccional. Se incluyeron todas las sesiones de cada terapia (N = 230) con el fin de identificar, delimitar, transcribir y analizar los Episodios de Cambio (EC =24) y Episodios de Estancamiento (EE = 26). Cada episodio además está conformado por segmentos de habla de las pacientes (N = 1.282) los cuales se constituyeron finalmente nuestra unidad de análisis. La codificación manual de cada uno de estos segmentos de habla se realiza a través del Sistema de Codificación de la Actividad Terapéutica (SCAT-1.0), los cuales fueron anidados en episodios e individuos para analizarlos posteriormente con el Modelo Jerárquico Lineal (HLM). Los resultados sugieren que las pacientes anaclíticas usaron más verbalizaciones con el fin de solicitar feedback o ser entendidas por sus terapeutas (sintonizar), mientras que las pacientes introyectivas usaron más verbalizaciones con el fin de construir nuevos significados (resignificar) durante la conversación terapéutica, incluso durante los episodios de EE. Se discuten las implicancias clínicas para el quehacer terapéutico.

Palabras clave: Episodio de cambio. Diálogo terapéutico. Acciones comunicacionales. Patrones comunicacionales. Organización de personalidad.

Therapeutic communication, specifically the speech of patients and therapists, is a dimension in which, microanalytically speaking, therapeutic change is constructed (Boisvert & Faust, 2003; Elliot, Slatick, & Urman, 2001; Krause et al., 2007; Llewelyn & Hardy, 2001; Orlinsky, Ronnestad, & Willutzki, 2004; Wallerstein, 2001). However, this activity has received less attention than the effectiveness of therapy or therapeutic outcomes (Asay & Lambert, 1999; Messer & Wampold, 2002; Wampold, 2005; Wampold, Ahn, & Coleman, 2001), or unspecific or common factors such as the therapeutic alliance (Hubble, Duncan, & Miller, 1999; Krause, 2005; Maione & Chenail, 1999; Meyer, 1990; Orlinsky & Howard, 1987). The conclusion that specific therapeutic interventions, associated with particular therapeutic models, are not the main causes of change (Lambert & Barley, 2001; Wampold & Brown, 2005) may be a bit rash. If therapeutic action were separated from specific schools, and studied in generic terms, seeking those shared by the different therapeutic approaches and modes, it would be possible to assess their actual contribution to the construction of the patient's change in therapeutic interaction.

There is growing evidence to support the idea that a person's verbal expressions makes it possible to identify significant indicators which reflect certain characteristics of his/her social processes and personality (Pennebaker, Mehl, & Niederhoffer, 2003). Based on the assumption that human beings do not act as a result of what things are, but according to their own representation of them, studying the way patients speak may lead to a better understanding of the subjective meanings (cognitive, affective, evaluative, and behavioral) that they ascribe to themselves and the relationship with their surroundings. The homogeneous effects of different therapeutic approaches in terms of their outcome (Matt & Navarro, 1997) have made it necessary to seek new and more convenient analysis systems capable of estimating psychotherapeutic change more accurately, and which can help in the formulation of theories based on empirical data. This has prompted, for example, studies devoted to understanding patient-therapist interaction (Williams & Hill, 2001). In addition, other work has focused on unspecific change factors in order to identify the internal and external factors of therapy which are instrumental in producing change, and which are also shared by all therapy types (Chatoor & Krupnick, 2001; Krause, 2005).

Classification Systems of Psychotherapeutic Dialog

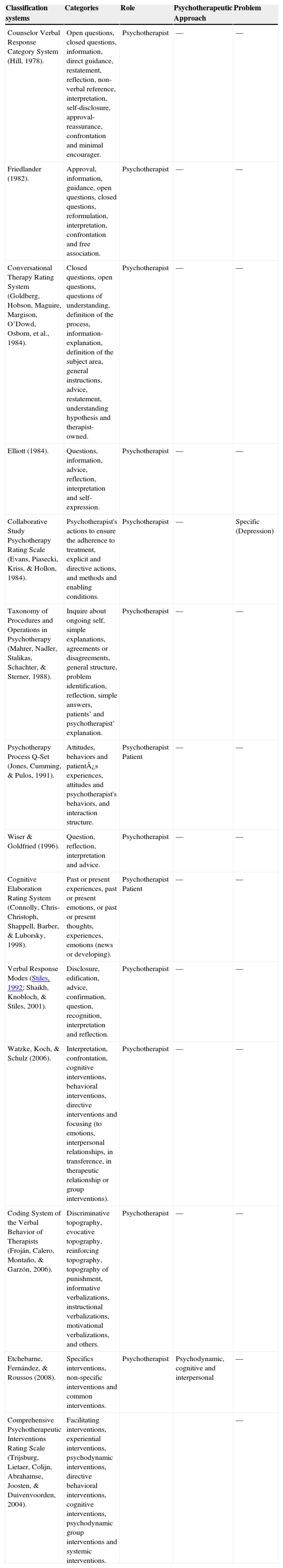

The main conclusions about the complexity of the series of processes involved in therapeutic interaction have highlighted the necessity of studying the said processes using different levels of analysis to attain a deeper understanding of them, and of developing new research methodologies for the systematic analysis of what occurs during the sessions (Hageman & Arrindell, 1999; Hill, 1990; Hill, O'Grady, & Elkin, 1992; Mahrer & Boulet, 1999; Stiles, Shapiro, & Firth-Cozens, 1990; Valdés, 2010; Valdés, Dagnino et al., 2010; Valdés, Krause, & Alamo, 2011; Valdés et al., 2005; Valdés, Tomicic, Pérez, & Krause, 2010;). Experts have developed systems to classify both patient and therapist verbalizations. Many of these classification systems were constructed only considering the therapists' utterances, while others can be applied to both therapists and patients (see Table 1). In addition, some of these systems have been constructed upon the basis of a specific therapeutic approach, or to analyze a particular therapeutic issue. However, even though most of them have proven useful for analyzing verbal interaction in psychotherapeutic dialog, it was deemed necessary to develop a single system for studying patients' and therapists' utterances, in order to describe therapeutic communication, understand its evolution, distinguish different types of episode, and identify change in psychotherapeutic processes of various approaches in different psychological problems.

Table 1. Systems for the Classification of Psychotherapeutic Dialogue.

Text analysis is one of the systems developed to determine multiple psychological dimensions based on people's speech. One of the methodological strategies used in psychology involves the analysis of each of the phrases in a text in order to generate codes, which has made it possible to identify individuals with different medical diagnoses (Gottschalk, Stein, & Shapiro, 1997), personality traits (Weintraub & Aronson, 1964), and cognitive and emotional dynamics (Stiles, 1992). This is the purpose of the Therapeutic Activity Coding System (TACS-1.0), a classification that enables researchers to analyze the nature of therapeutic language in itself, which includes both the performance of actions by patients when they speak and the transmission of contents which are directly associated with the object of therapeutic work. This twofold notion of verbal communication makes it possible to analyze therapeutic activity by identifying variable actions whereby patients and therapists influence each other without losing track of content, as both dimensions participate in the construction of psychological change (Valdés, Tomicic et al., 2010).

During the therapeutic conversation, therapists' and patients' verbal expressions take the form of "communicative patterns" (CP), which allow them to coordinate communication within themselves and with the other participant during the therapeutic activity (Valdés, 2014). Bearing this in mind, verbal expressions are analyzed using a process-based approach that leads to understanding therapeutic change as a change in meanings, that is to say, as a representational modification. Said change has been associated with the patient's subjective view of him/herself, his/her problems and symptoms, and the connection between such issues and the environment in which they occur (Krause et al., 2007). In other words, therapeutic change can be understood as a patient's construction of new Subjective Theories about his/her self and his/her relationship with the world, upon the basis of connections constructed gradually through associations which result from a successive process of resignification. Such associations are fostered during segments of the session considered significant or relevant for change according to certain criteria, and are also expressed at a communicative level during therapeutic conversation.

Anaclitic and Introjective Personality Configurations

According to Blatt (1992, 2008), personality development involves the achievement of a differentiated and consolidated identity; yet, it is also necessary to develop stable, enduring, and mutually satisfying interpersonal relationships. A distorted preoccupation with one task over the other allows us to identify two personality configurations: the first has been termed "anaclitic personality", which is characterized by disruptions of gratifying interpersonal relationships (e.g., object loss or neglect), while the second has been termed "introjective personality", which is characterized by disruptions of an effective and essentially positive sense of self (e.g., feelings of failure or guilt). Extensive research has been conducted showing important differences between anaclitic and introjective personality, thus demonstrating the validity of diagnosing both configurations to understand a wide range of psychopathology, specifically within depression and personality disorders. Furthermore, anaclitic and introjective configurations involve a different experiential mode and behavioral orientation, with very different types of gratification and preferred modes of cognition, defense, and adaptation. Therefore, each group of patients is expected to experience the psychotherapeutic process differently, which may be reflected in their speech.

The distinction between anaclitic and introjective personality derives primarily from psychodynamic considerations, including differences in instinctual focus (libidinal vs. aggressive), types of defensive organization (avoidant vs. counteractive), and predominant character style (e.g., emphasis on an object vs. self-orientation, and on affects vs. cognition). Anaclitic individuals use predominantly avoidant defenses such as denial, repression, and displacement, in an effort to maintain interpersonal ties, because of an exaggerated and distorted emphasis on interpersonal relatedness (Blatt, 2008; Blatt & Blass, 1996). However, the development of the self is neglected and defined primarily in terms of the quality of interpersonal experiences; thus, these individuals are very dependent and vulnerable to experiences of abandonment. Relatedness refers to feelings of loss, sadness, and loneliness in reaction to the disruption of relationships. These feelings are not undifferentiated and nonspecific; rather, they reflect concerns about the loss of a special person to whom one feels attached. Dependence refers to feelings of helplessness, fear, and apprehension about separation and rejection, and intense and broad-ranging concerns about a general loss of contact with others, unrelated to a particular relationship. These items reflect a desperate need for others but with little differentiation or specification of any particular person or relationship. By contrast, an exaggerated and distorted preoccupation with establishing and maintaining definition of the self at the expense of establishing meaningful interpersonal relations defines the psychopathologies of the introjective patients (Blatt, 2008; Blatt & Blass, 1996). The primary preoccupation with self-definition in these configurations distorts the quality of interpersonal experiences, which makes these individuals very vulnerable to feelings of failure, criticism, and guilt. These individuals tend to use counteractive rather than avoidant defenses including isolation, doing and undoing, intellectualization, reaction formation, introjection, identification with the aggressor, and overcompensation in an effort to preserve a consolidated sense of self.

Each configuration responds differentially to different types of psychotherapeutic intervention: anaclitic patients appear to respond primarily to the supportive interpersonal or relational dimensions, whereas introjective patients appear to respond primarily to the interpretive or explorative aspects of the treatment process (Blatt & Shahar, 2004). Regardless of the therapeutic approach used and the course of the therapy, both groups of patients display different contents of therapeutic change. For example, introjective patients change primarily in terms of the frequency of their clinical symptoms as well as the level of their cognitive functioning; therefore, psychotherapeutic changes occur more slowly and more subtly in anaclitic patients, who express those changes primarily through the quality of their interpersonal relationships. Such findings suggest that these two personality configurations might also have divergent responses to different therapeutic intervention forms, or to each of the phases of the therapeutic process.

Based on a performative view of language (Reyes et al., 2008; Searle, 1980, 2002), which stresses that every time a patient says something, he/she is also doing something, and assuming that communicative patterns are defined by the communicative actions that patients use, the most relevant of such actions employed during the therapeutic conversation in relevant episodes of the therapy were studied considering different levels of analysis. Some of these episodes were related to the process of co-construction of new meanings with therapists, while others were associated with a temporary halting of the patient's change process due to a reemergence of the problem. The aim of the present study was to identify the presence of verbal micromarkers in the speech of patients, depending on episode type, phase of the therapeutic process, and symptomatology. In addition, we expected to predict the appearance of those verbal micromarkers depending on whether the patient has an anaclitic or an introjective personality configuration (Blatt & Shichman, 1983).

Hypotheses

The present study was guided by the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: certain verbal micro markers make it possible to differentiate Change Episodes (CE) and Stuck Episodes (SE), regardless of the patients' symptoms and personality style.

Hypothesis 2: introjective patients resignify more than anaclitic patients, while the latter use more verbalizations in order to attune.

Hypothesis 3: anaclitic patients focus their work on contents referred to a third party, compared to introjective patients.

Hypothesis 4: both anxious and depressive patients work on affective contents throughout the therapeutic process; however, depressive patients do it more extensively during the final phase compared to anxious patients.

Hypothesis 5: the resignification of contents is higher during the final phase of therapy, compared with the initial phase.

Hypothesis 6: introjective patients resignify more cognitive contents, while anaclitic patients resignify more contents referred to themselves.

Method

Sample

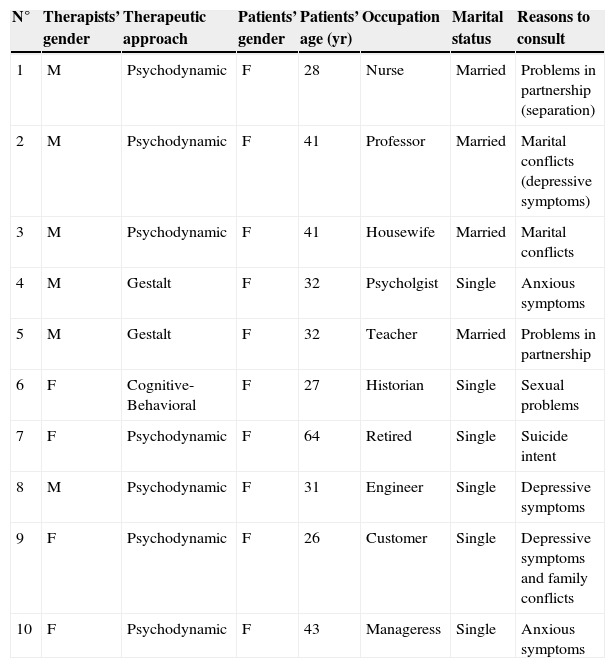

Ten therapies conducted in Chilean private therapeutic centers were analyzed (see Table 2). All the therapies are part of the Therapeutic Processes Database provided by the Chilean Millennium Nucleus Project, which has generated audiovisual recordings over the last years with the purpose of conducting process analysis. The therapies were intentionally selected according to the following criteria: (a) therapies with a weekly individual modality, (b) therapists with 10 to 30 years of professional experience, (c) therapies with a significant degree of change as well as an evolution of change throughout the process, and (d) participants who gave their informed consent to participate in the study. The therapies carried out included 10 women aged between 26 and 64 (M = 37, SD = 10.93).

Table 2. Characteristics of Therapeutic Processes.

Procedure and Instruments

Therapeutic outcome. Therapeutic outcomes were estimated using the Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45.2), developed by Lambert et al. (1996), and validated for Chile by Von Bergen and de la Parra (2002). A high total score in the questionnaire means that the patient reports a high level of unhappiness in spite of his/her high quality of life, which is expressed through his/her symptoms, interpersonal relationships, and social role. The interpretation of the results is based on a Reliable Change Index (RCI), which determines whether the patient's change at the end of the treatment is clinically significant (RCI for Chile =17; Jacobson & Truax, 1991). In this study, patients displayed a significant degree of change during the therapy (A = 19.6, B = 20). The List of Generic Change Indicators was used to estimate the evolution of therapeutic change (Krause et al., 2007), considering both the amount and levels of change moments throughout the process. A significant increase in the patients' openness to new forms of understanding was observed (Level II). The consolidation of the structure of the therapeutic relationship (Level I) was more frequent during the initial stages of the process, while both patients were capable of constructing and consolidating a new way of understanding themselves at the end of the process (Level III).

Classification of the therapies according to the predominant symptoms. Ten therapies met the above-mentioned requirements; however, the next step was to classify them according to the predominant symptoms, regardless of the reasons for consulting. For this purpose, an Observation Guideline for the Diagnosis of Depressive Symptoms was developed (Salvo, Cordes, & Valdés, 2012) for identifying those patients who were seeking psychotherapeutic help because of their depressive symptoms. This Observation Guideline initially includes an item which captures the existence of criteria related to psychotic disorders, substance-related disorders, dementia and other cognitive disorders, mental retardation, and antisocial personality disorder. Subsequently, the observers had to analyze the patients' narratives and observed behavior in order to identify the predominance or absence of depressive symptoms. They had to register in which minute and in which speaking turn the criterion was met during the patients' verbalizations, and also note whether the temporal criterion for a Major Depression was met (a minimum of two weeks).

The first part of the guideline was constructed on the basis of the criteria for a Major Depression set out in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). However, it does not claim to diagnose a depressive or any other mood disorder; instead, it is used for capturing the presence or absence of depressive symptoms (Salvo et al., 2012). The presence of depressive symptoms was approved if one of the first two items was answered affirmatively. However, if the temporal requirement of a minimum of two weeks was also met in all the observed criteria, the observer was able to diagnose a Major Depression according to the DSM-IV-TR.

Using this Observation Guideline, an inter-rater reliability study was conducted for classifying all the therapies according to the patients' predominant symptoms. A diagnostic examination based on the first two video-taped sessions of the 10 included therapies was conducted by three observers with at least five years of clinical experience, in order to identify those patients who were seeking psychotherapeutic help due to the predominance of depressive symptoms. The reliability study was carried out in the following three successive stages: a) two observers individually coded each item of the Observation Guideline; b) they discussed their coding in order to reconcile their differences and to make a final decision about the presence or absence of depressive symptoms in each patient. If necessary, they additionally watched a part of the videos or read the transcriptions again to reach a consensus based on the data; and c) this last coding was compared again with the assessment of a third observer, who rated the therapy sessions following the same principles and procedure mentioned above.

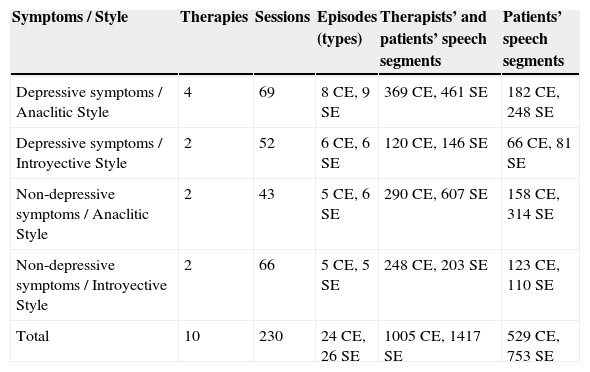

The degree of agreement for coding each item of the guideline was calculated using the Cohen's kappa between the joint judgment of the first two observers and the judgment of a third observer. The degree of agreement varied from moderate to perfect in ten of the items, showing no significant effects only in items four (ĸ = .375, p = .236) and eight (ĸ =-.364, p = .197). However, the items which most directly reflect the main criteria and the final diagnostic conclusion for depressive symptoms showed a moderate to high degree of agreement between the observers. According to the first part of the guideline, the total sample was distributed as follows: 6 patients with a predominance of depressive symptoms and 4 patients with a predominance of anxious symptoms (see Table 3).

Table 3. Distribution of therapists' speech segments according to episode type,

as well as patients' symptomatology and personality style.

Note. CE = Change Episodes, SE = Stuck Episodes

Classification of patients according to their depressive personality styles. Additionally, the Observation Guideline developed has a second part to differentiate the predominance of one of the following depressive personality styles: Anaclitic, Introjective and Mixed. These styles were proposed by Blatt in 1974, as a result of psychoanalytic theoretical formulations and clinical observation of depressive patients. Some items present in the Depressive Experiences Questionnaire (DEQ; Blatt, D'Afflitti, & Quinlan, 1976) were included in the guideline to allow observers to identify the patient's predominant depressive style. Research has shown that the concepts of dependency and self-criticism are closely related to these styles: for example, the symptomatology of depressed patients reveals few differences among them, but these depressive styles are much more effective in highlighting variation. A depressed patient with an Anaclitic personality style is characterized by deep feelings of loss and loneliness, while a depressed patient with an Introjective personality style is characterized by intense feelings of worthlessness (Blatt, 2008). The same reliability study showed a high degree of agreement between the observers when differentiating the patients' personality styles (items 12 and 13). Therefore, according to the second part of the Observation Guideline, the total sample was distributed as follows: 6 anaclitic patients and 4 introjective patients (see Table 3).

Demarcation of change and stuck episodes. The ten videotaped therapies were observed by expert raters trained in the use of a protocol for detecting and identifying relevant moments during therapeutic sessions (Krause et al., 2007). All the sessions were listed in chronological order and transcribed to facilitate the subsequent delimitation of the Change Episodes (CE) and Stuck Episodes (SE).

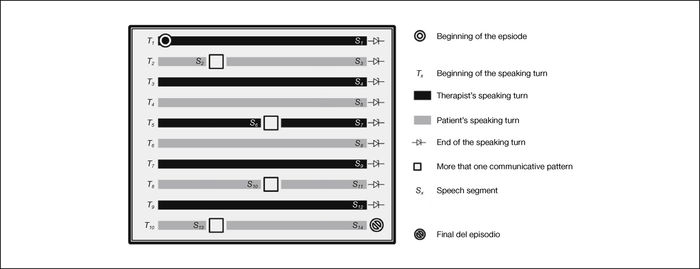

As shown in Figure 1, the moment of change marks the end of the CE. Said moment of change must meet the criteria of theoretical correspondence, novelty, topicality, and consistency; that is, they must match one of the indicators from the Hierarchical List of Change Indicators (GCI; Krause et al., 2007), being new, occurring during the session, and persisting over time. Afterwards, using a thematic criterion, the beginning of the therapeutic interaction referring to the change moment is tracked in order to define the start of the CE.

Figure 1. Delimitation of a Change Episode and a Stuck Episode (Valdés, 2012, p.160).

In the case of SEs, it was necessary to identify those periods of the session in which there was a temporary halting of the patient's change process due to a reissue of the problem, that is, episodes of the session characterized by a lack of progressive construction of new meanings (Herrera et al., 2009). A SE must also match one of the topics from the List of Stuck Topics, occur during the session, and be nonverbally consistent with the topic of that kind of episode. In addition, a SE must comply with the following methodological criterion: be at least three minutes long and be at least 10 minutes apart from a CE in the same session.

All the sessions of each therapy were considered in order to transcribe, delimit, and analyze all the CEs and SEs identified (see Table 3). Specifically, 50 episodes included in 230 sessions were analyzed. Each episode was made up of patients' and therapists' speaking turns, which began with the start of one participant's verbalization and ended when the other's began (Krause, Valdés, & Tomicic, 2009). Moreover, each speaking turn was divided into speech segments - the sampling unit - depending on the presence of two or more Communicative Intentions coded within a single speaking turn (see Figure 2). Therefore, the total sample comprised 1,282 patients' speech segments, 529 of which were included in CEs and 753 were part of SEs.

Figure 2. Segmentation of speaking turns. According to the TACS-1.0 Manual, this example

of episode has 10 speaking turns (Tx) and 14 speech segments (Sx) (Valdés, 2012).

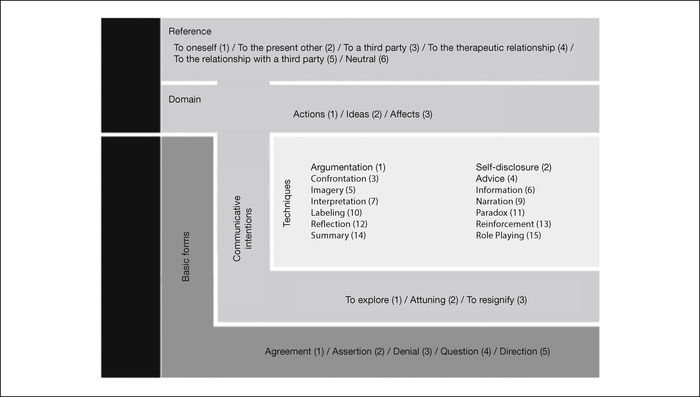

Characteristics of communicative actions. The Therapeutic Activity Coding System (TACS-1.0; Valdés, Tomicic et al., 2010) was used to manually code the verbalizations present in patients' speech segments during the CEs and SEs delimited. Verbalizations were termed Communicative Actions, because they have the double purpose of conveying information (Contents) and exerting an influence on the other participant and the reality constructed by both speakers (Action). This system is based on a performative view of language, and was developed in order to reveal the complexity and multidimensionality of communicative interaction in psychotherapy (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Dimensions and categories of the Therapeutic Activity Coding System, version 1.0 (Valdés et al., 2010).

The TACS-1.0 is made up by five parallel and non-inclusive categories of analysis; three of them belong to the Action dimension while two belong to the Content dimension. The categories that include the 22 Action codes are: Basic Form (formal structure of the utterance), Communicative Intention (communicative purpose expressed during the utterance), and Technique (methodological resources present in the utterance, some of which coincide with therapeutic techniques, while others are typical of everyday interaction). On the other hand, the categories that include the 9 Content codes are: Domain (cognitive, affective, or behavioral) and Reference (protagonist of the object of therapeutic work).

A second reliability analysis was carried out to evaluate the degree of agreement between the coders of the speech segments included in the CEs and the SEs. In order to do this, a sample of 268 speech segments was selected at random (11% of the total sample) to calculate Cohen's kappa for each of the five TACS-1.0 categories. The results are the following: Basic Form (k = .95, p =.000), Communicative Intention (k = .70, p =.000), Technique (k = .51, p =.000), Domain (k = .73, p =.000), and Reference (k = .79, p =.000). Therefore, the reliability of the raters' coding of the CEs and the SEs ranged from average to very good.

Characteristics of patients' communicative patterns. The resulting code configuration of each speech segment was analyzed. This configuration was termed "communicative pattern" (CP), and was generated using the combination of digits assigned to each TACS category (Valdés, Krause, Tomicic, & Espinosa, 2012). All the CPs have two levels separated by a hyphen: the first level is referred to as Structural Level and includes three digits corresponding to a specific content associated with the object of therapeutic work (domain), which is transmitted with a certain purpose (communicative intention) and using a certain formal structure (basic form); in contrast, the second level is referred to as Articulative Level and includes the last three digits corresponding to the participant that emits the information (reference) and the presence or absence of any resources used by the speaker to provide support for the purpose of his/her verbalization (technique). In other words, two CPs can have the same characteristics at the Structural Level, but, at the same time, they can be articulated differently depending on the circumstances present in a given moment of the conversation, which does not affect their structure. For example, a patient could use the CP213-101 in order to explore (second digit, 1) affective contents (third digit, 3) using an assertion as formal structure (first digit, 2), but also these contents are referred to herself (fourth digit, 1) and uses argumentations to support the communicative intention present in this speech segment (fifth-sixth digits, 01).

The present study analyzed all the Communicative Actions considering the categories present in the TACS-1.0 (Basic Form, Communicative Intention, Technique, Domain, and Reference), as well as some of the Communicative Patterns configured from such categories.

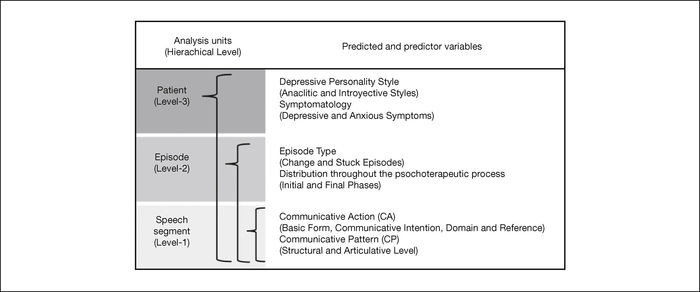

Data Analysis

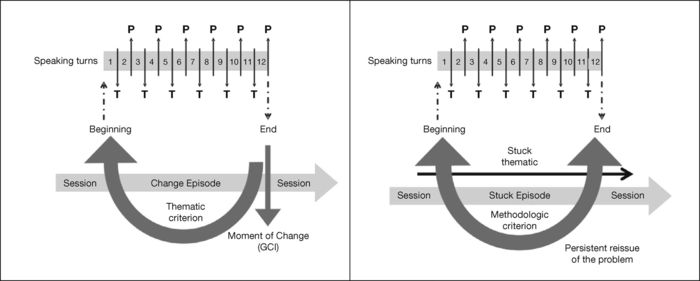

Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) was used to analyze variance in the outcome variables (CAs and CPs) because they are nested in the predictor variables, which are in a different hierarchical level (Woltman, Feldstain, MacKay, & Rocchi, 2012). Therefore, the hypotheses advanced in this study involve a three-level hierarchy. The highest level (Level-3) contains the patient-related variables, such as symptomatology and personality style (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Factors at each hierarchical level that predict patients' verbalizations.

Episode-related variables are situated at the middle level of the hierarchy (Level-2). Level-2 variables are nested within and impacted by Level-3. Speech segment-related variables, such as verbalizations with the presence of specific CAs or CPs are situated at the lowest level (Level-1). The Level-1 predicted variables are nested within and impacted by the Level-2 predictor variables. In HLM, the outcome variable of interest is always situated at the lowest level of the hierarchy. For example, patients verbalize specific communicative actions (Level-1) during Change Episodes (Level-2) depending on their personality style (Level-3).

Results

Analyses revealed several results related to the patients' verbal expressions used during the therapeutic conversation. Those results were organized as follows: first, patients' CAs predicted only from the episode type using a two-level model; second, patients' CAs predicted from the episode type, but also considering symptomatology, personality style, and the phase of the therapeutic process (three-level model); and finally, the CPs predicted from episode type, symptomatology, personality style, and the phase of the therapeutic process (three-level model).

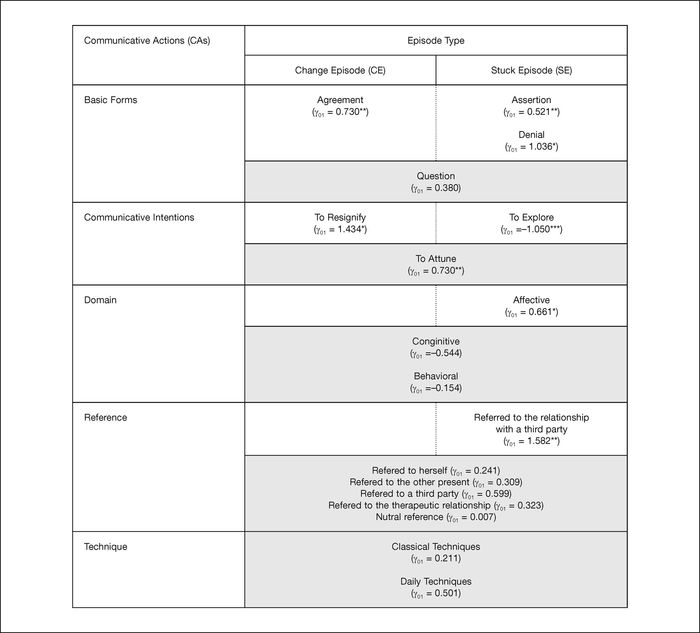

Predicting Communicative Actions (CAs) from Relevant Episode Type (CE and SE)

The first category of the TACS-1.0 has been termed Basic Form and makes it possible to classify the formal structure of the patient's verbalization, distinguishing between the following communicative actions: agreement, assertion, denial, and question. Patients are more likely to use verbalizations with agreement (e.g., "yes", "right", "of course", "maybe", "mhm") during CEs (OR = 2.07, p = .002), compared to SEs. However, the opposite occurs with the use of assertions (e.g., "but he always tried to support me, even when I left him", "she did it to commit herself", "impossible to know") (OR = 0.59, p = .006) and denial (e.g., "no", "no way") (OR = 0.35, p = .029), which are more frequently used by patients during SEs. The only verbalizations used by patients with the same probability for both episode types are those with a question as a basic form (e.g., "and what do I have to do, then?", "can you understand me?").

The second category of the TACS-1.0 has been termed Communicative Intention and makes it possible to classify the communicative purpose of the patient's verbalization, that is, what the speaker wants to achieve with it. This category includes the following communicative actions: exploring, attuning, and resignifying. The patients are more likely to use explorations during SEs (OR = 0.35, p < .001), in order to find out, provide or clarify unknown contents, and/or direct the therapist's attention towards a specific aspect of the conversation (e.g., "let me tell you something that happened to me this weekend", "I mean, I won't complete my university degree"). However, the probability of patients using resignifications in order to co-construct and/ or consolidate new meanings is highest during CEs (OR = 11.19, p < .001) (e.g., "I think that this thing of being so serious and boring has to do with how my father educated me", "deep inside, I never wanted to stop being a child"). The only verbalizations used by patients with the same probability during both episode types are those used to attune - to ask the other speaker for feedback, or to be understood by the therapist (e.g., "I need you to understand what I'm trying to explain", "what you just said bothered me").

The third category of the TACS-1.0 has been termed Technique and makes it possible to classify the methodological resources present in the patient's verbalization to support the communicative intention during a speaking turn. This category includes the following communicative actions: eight psychotherapeutic techniques which characterize certain psychotherapeutic approaches (confrontation, imagery, interpretation, labeling, paradox, reflection, reinforcement, and role-playing) and six communicational resources typical of everyday interaction (argumentation, self-revelation, advice, information, narration, and summary). All of these methodological resources have the same probability of being used in both CEs and SEs.

The fourth category of the TACS-1.0 has been termed Domain and makes it possible to classify the patient's verbalization depending on whether the object of the therapeutic work is mostly cognitive (ideas), emotional (affects), or behavioral (actions). The results showed that patients are more likely to work on affective contents during SEs (OR = 0.52, p = .042), in order to focus on emotions, feelings, or moods (e.g., "that's why I cannot feel any pleasure, I think in that case I would feel very sad"). However, both cognitive (e.g., "I think that is why I'm like this, because I do not take advantage of the time of others") and behavioral contents (e.g., "when they start quarreling, I just stay away") have the same probability of being worked on by patients during both episode types.

The last category of the TACS-1.0 has been termed Reference and makes it possible to classify the patient's verbalization depending on whether it is referred to herself (e.g., "I try to be as honest as I can, but I can't tell if it's really like that"), referred to the therapist (e.g., "do you think it is possible?"), referred to a third party (e.g., "they don't understand me, they are not patient with me"), referred to the therapeutic relationship (e.g., "you have helped me become aware of things I had never realized before"), referred to the relationship with a third party (e.g., "my husband and I couldn't agree on this subject"), or if it has a neutral reference (e.g., "that is the question exactly"). Patients are more likely to work on contents referred to their relationship with a third party during SEs (OR = 0.21, p = .002), while all the others are worked on by patients with the same probability during both CEs and SEs.

In summary, hypothesis 1 was confirmed: there are communicative actions that could be considered as verbal micromarkers to characterize the therapeutic conversation during CEs and SEs, regardless of the patients' symptoms and personality style. Specifically, more agreement and resignifications are associated with the therapeutic work during CEs, while the work done during SEs is associated with more assertions, denial, explorations, affective contents, and verbalizations referred to the relationship with a third party (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Differences between Change Episodes and Stuck Episodes depending

on the Communicative Actions predicted by the episode type (Level-2).

Predicting CAs from Episode Type, Symptomatology and Personality Style

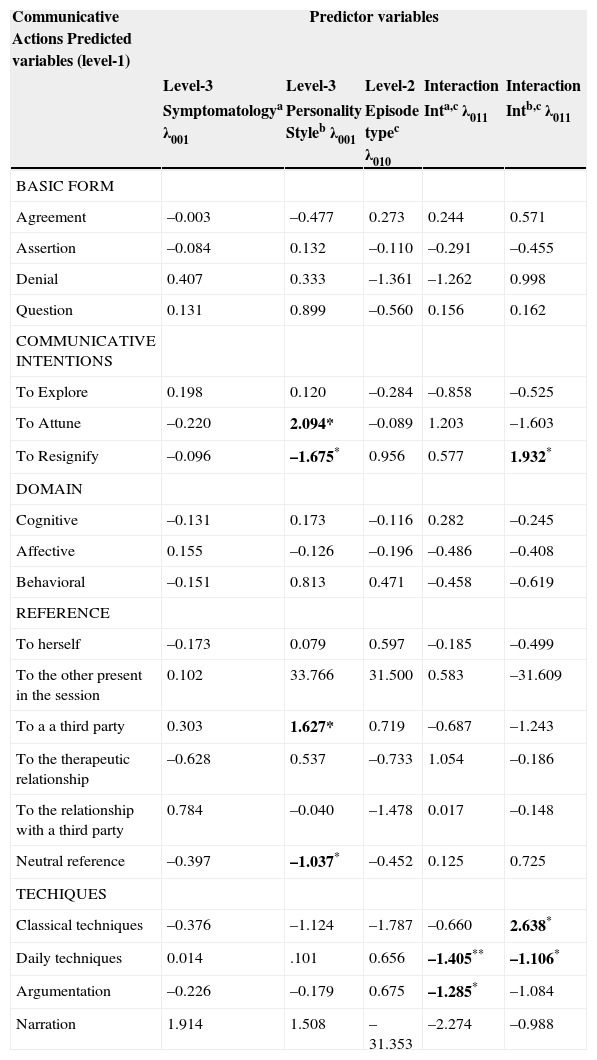

When the symptomatology and personality style were considered in the model, the results showed that all the basic forms mentioned above were used by patients with equal probability of occurrence during CEs and SEs (see Table 4). Therefore, the use of these formal structures is mediated by the patient-related variables, but their occurrence is neither directly predicted by these Level-3 variables, nor by an interaction between levels.

Table 4. Hierarchical non-linear modelling results with Communicative Action as dependent

variable, the Episode Type as independent variable entered on Level-2 (fixed effect,

γ010), Symptomatology and Personality Style as independent variables entered separately

on Level-3 (fixed effect, γ001), and adding the interaction of the variables

mentioned above to the model, (fixed effect, γ011).

Note. acontrolling depressive symptoms and anxious symptoms as Level-3 predictors;

bcontrolling anaclitic personality and introjective personality style as Level-3 predictors;

ccontrolling change episode and stuck episode as Level-2 predictors; a,cadding the

interaction term to the model with symptomatology and episode type; and

b,cadding the interaction term to the model with personality style and episode type.*

p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Regarding communicative intentions, the results showed that patients explore contents with equal probability for both episode types when symptoms and personality style were considered (see Table 4). However, personality style can be employed to predict the occurrence of patients' verbalizations used in order to resignify. Introjective patients are more likely to use resignifications during the therapeutic conversation (OR = 0.19) compared with anaclitic patients. Even more so, there is an interaction effect between the patient's personality style and the episode type which predicts the probability of occurrence of such verbalizations. Therefore, the construction of new meanings during SEs is greater in introjective patients (OR = 0.20, p = .0004) compared with anaclitic patients. The resignification of contents during CEs is independent of the patient's personality style; therefore verbalizations of this kind have the same probability of being used by patients with either personality style. The Level-3 variables have no effect on the episode type as a Level-2 predictor variable; however, it is possible to directly predict the probability of occurrence of patients' verbalizations used in order to attune based on personality style. Thus, anaclitic patients are more likely to use this communicative action than introjective patients (OR = 8.12), regardless of the relevant episode type. Therefore, hypothesis 2 was also confirmed.

The two-level analysis showed that the probability of using techniques to support the speaker's communicative purposes does not depend on the episode type. However, this observation does not apply when symptomatology and personality style are considered (see Table 4). On the one hand, the use of techniques depends on the interaction effect between personality style and the episode type in which they are used. Thus, introjective patients are more likely to favor classical techniques during SEs (OR = 0.33, p = .041) and communicational resources typical of everyday interaction during CEs (OR = 0.50, p = .004) compared to anaclitic patients. On the other hand, the probability of occurrence of the latter group of techniques can be predicted by the interaction effect between the episode type and the patient's symptoms. Results showed that anxious patients are more likely to use techniques typical of everyday interaction during CEs (OR = 0.24, p < .000) compared to depressive patients.

The two techniques most frequently used by patients during relevant segments of the session are argumentation and narration. In the first case, the speaker provides support, an example, a generalization, or justification for a content (e.g., "I've been feeling the urge to consume because I'm very tired, down", "for example when I made the choice not to call him anymore", "I won't cry because men never cry"). The use of this communicational resource in each episode type depends on the symptomatology presented by the patient: anxious patients are more likely to use arguments during CEs (OR = 0.22, p < .000), while depressive patients use them more frequently during SEs (OR = 0.37, p = .001) (see Table 4). In the second case, when a narration is used, the speaker verbalizes contents which refer to a succession of events taking place at a certain period of time (e.g., "that time, he told me that he didn't want to be with me anymore, and I panicked, and asked him to please give another chance to our relationship. From that moment on, he began arriving home very late, almost every night"). The results showed that narration is a technique used with the same probability in both episode types, regardless of the patients' symptomatology and personality style.

As shown in Table 4, patients' verbalizations used to work on affective, cognitive, and behavioral contents not only have the same probability of occurrence in both episode types, but are used regardless of the type of symptoms and personality style.

When episode type was considered as the only predictor variable in the two-level analysis, the results showed that the probability of occurrence of verbalizations referred to the patient's relationship with a third party was higher during SEs (see Table 4). Therefore, such verbalizations and those referred to themselves, referred to the other present (therapist), and referred to the therapeutic relationship, are equally likely to be used by patients, regardless of the episode type, type of symptoms, and personality style. However, both the verbalizations referred to a third party and those with a neutral reference can be used regardless of the episode type and the type of symptoms, but their probability of occurrence does depend on the patients' personality style. Thus, hypothesis 3 was confirmed: anaclitic patients are more likely to work on contents referred to a third party than introjective patients (OR = 5.09), while the latter are more likely to work on contents with a neutral reference during the therapeutic conversation (OR = 0.35).

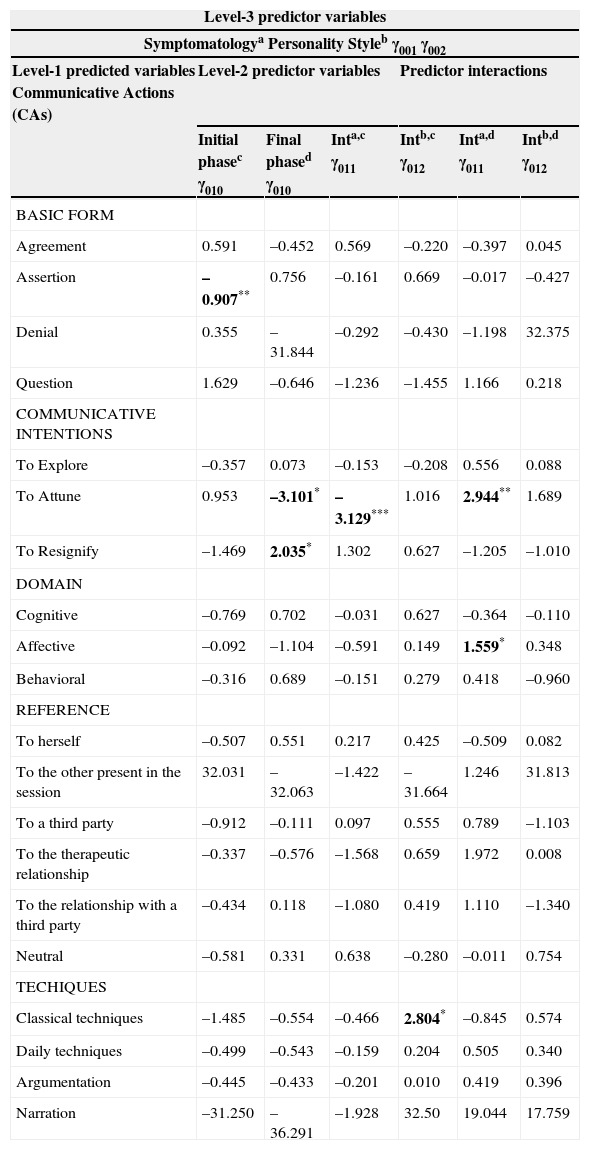

Predicting CAs from the Phase of the Therapeutic Process

It is possible to predict the probability of occurrence of verbalizations with an assertion as a basic form during the initial phase of therapy, when the patient's symptoms and personality style are considered as a Level-3 predictor variable (see Table 5). There is a high probability that patients use fewer assertions to work on contents during the first third of therapy (OR = 0.40) compared to the last two thirds measured together (middle and final phase). However, the verbalizations with an agreement, a denial, or a question as a basic form are not predicted by the phase of therapy; therefore, they are used by patients with equal probability during the first third (initial phase) and the last third of therapy (final phase).

Table 5. Hierarchical non-linear modelling results with Communicative Actions as

dependent variable, the Initial and Final Phase as independent variables entered on

Level-2 (fixed effect, γ010), Symptomatology and Personality Style as independent

variables entered separately on Level-3 (fixed effect, γ001 and γ002, respectively),

and adding the interaction of the variables mentioned above to the model, (fixed

effect, γ011 and γ012, respectively). Independent variables could be significant

when the interaction is also significant (fixed effect, β02).

Note. acontrolling depressive symptoms and anxious symptoms as Level-3 predictors;

bcontrolling anaclitic personality and introjective personality style as Level-3

predictors; ccontrolling initial phase and the last two-thirds of the therapy

together as Level-2 predictors; dcontrolling final phase and the first two-thirds of

the therapy together as Level-2 predictors; a,cadding the interaction term to the

model with symptomatology and initial phase; b,cadding the interaction term to the

model with personality style and initial phase; a,dadding the interaction term to

the model with symptomatology and final phase; and b,dadding the interaction term to the

model with personality style and final phase.* p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

The verbalizations used in order to explore are applied by patients with the same probability throughout the therapeutic process (see Table 5). Therefore, this communicative intention is used independently of the patient's symptoms, personality style, and the phase of the therapy. However, the probability of occurrence of verbalizations used to resignify contents is predicted by the phase of the therapy. Therefore, hypothesis 5 was confirmed: patients use more verbalizations in order to resignify contents during the final phase of the therapeutic process (OR = 0.91) compared to the first two thirds of the therapy taken together (initial and middle phase). In contrast, verbalizations used to attune are not only more likely in depressive patients (OR = 4.82); also, their probability of occurrence depends on the interaction effect between the patients' symptoms and the initial phase of therapy. Results showed that depressed patients tend to attune more often than anxious patients and that they do it less often during the initial phase of therapy (OR = 0.15, p < .000), but more frequently during the final phase (OR = 15.60, p = .000).

Patients used verbalizations to work on cognitive and behavioral contents with equal probability throughout the therapeutic process; therefore, such contents are worked on regardless of the patients' symptoms, personality style, and the phase of therapy (see Table 5). However, the probability of working on affective contents during the final phase of therapy depends on the patient's symptomatology. Hypothesis 4 was thus confirmed: depressive patients are more likely to work on affective contents than anxious patients during the final phase of the process (OR = 2.79, p = .006), compared to what happens during the first two thirds of the therapy taken together (initial and middle phases).

Contents referred to the patients themselves, to the other present (therapist), to a third party, to the relationship with a third party, and to the therapeutic relationship, as well as those with a neutral reference, are worked on with equal probability throughout the therapeutic process, regardless of the patients' symptomatology and personality style, and during all phases of therapy (see Table 5). The same result was found when the techniques typical of everyday interaction were analyzed. However, the probability of using classical techniques to support the communicative purpose during the initial phase of therapy does depend on the patients' personality style. Patients with both personality styles are highly likely to use such technical resources during the initial phase of therapy, while introjective patients will use them more during the last two thirds of the therapeutic process (OR = 0.15, p < .000) compared to anaclitic patients.

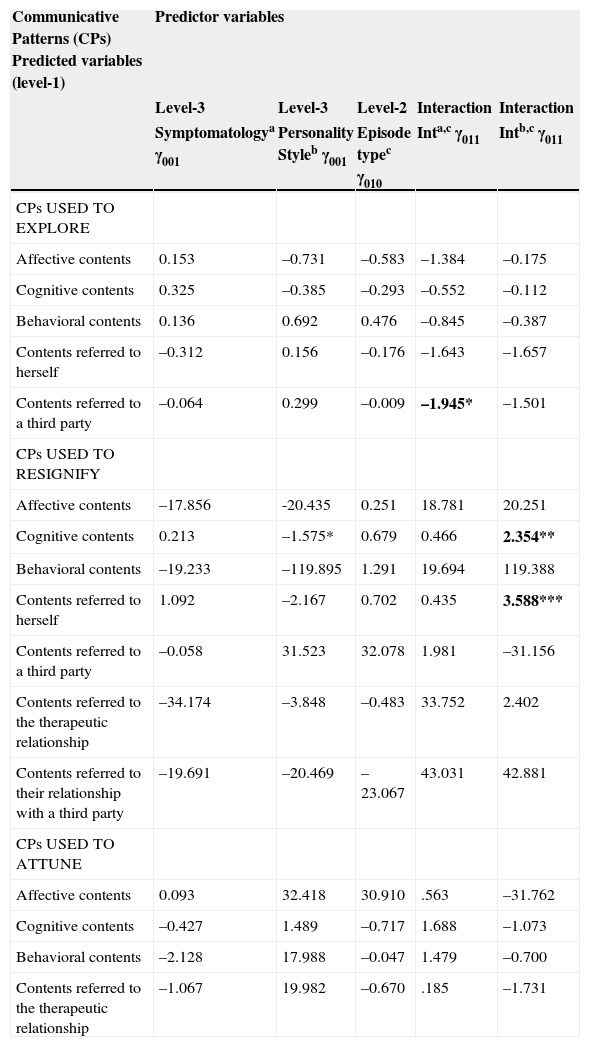

Predicting CPs from Symptomatology, Personality Style, and Episode Type

The top section of Table 6 presents the final model predicting the 5 Communicative Patterns (CPs) used by patients to convey a content, clarify it, and/or direct the therapist's attention to certain contents, which are grouped as follows: at a structural level, there are 3 CPs related with the exploration of contents depending on the domain worked on during the psychotherapeutic dialogue (cognitive exploration, affective exploration, and behavioral exploration), while at an articulative level, there are 2 CPs related with the exploration of contents depending on who the protagonist of the therapeutic work is (exploration referred to herself and exploration referred to a third party). All these CPs are used by patients with equal probability during the conversation, regardless of the symptoms, personality style, and even the episode type. However, the exploration referred to a third party is the only CP whose probability of occurrence can be predicted by the interaction effect between the symptoms and the episode type. Thus, it is more likely to explore contents related to a third party during CEs (OR = 0.31, p = .000) compared to depressive patients. According to the personality style, both anaclitic and introjective patients use this CP with the same probability during SEs.

Table 6. Hierarchical non-linear modelling results with Communicative Pattern as dependent

variable, the Episode Type as independent variable entered on Level-2 (fixed

effect, γ010), Symptomatology and Personality Style as independent variables entered

separately on Level-3 (fixed effect, γ001 and γ002, respectively), and adding the

interaction of the variables mentioned above to the model, (fixed effect, γ011 and

γ012, respectively). Independent variables could be significant when the interaction is also

significant: (1) initial phase γ002=1.828*, (2) initial phase γ001=1.572*, (3) final phase

γ002=1.359*, and (4) final phase γ002=-0.957*.

Note. acontrolling depressive symptoms and anxious symptoms as Level-3 predictors;

bcontrolling anaclitic personality and introjective personality style as Level-3 predictors;

ccontrolling change episode and stuck episode as Level-2 predictors; a,cadding the

interaction term to the model with symptomatology and episode type; and b,cadding

the interaction term to the model with personality style and episode type.* p < .05, **

p < .01, *** p < .001.

The middle section of Table 6 presents the 7 CPs used by patients to co-construct and/or consolidate new meanings for certain contents that have been worked on during the therapeutic conversation, which are grouped as follows: at a structural level, there are 3 CPs related with the resignification of contents depending on the domain worked on during the psychotherapeutic conversation (cognitive resignification, affective resignification, and behavioral resignification), while at an articulative level there are 4 CPs related with the resignification of contents depending on who the protagonist of the therapeutic work is (resignification referred to herself, resignification referred to a third party, resignification referred to the relationship with a third party, and resignification referred to the therapeutic relationship). In the first group, cognitive resignification is the only CP whose probability of occurrence can be predicted by the patient's personality style, with introjective patients being more likely than anaclitic patients to resignify cognitive contents (OR = 0.21). The first part of hypothesis 6 was confirmed, but this CP can be also be predicted by the interaction effect between personality style and the episode type. However, it is interesting that anaclitic patients resignify more cognitive contents during CEs (OR = 2.28, p = .009), while introjective patients mostly do it during SEs (OR = 0.21, p = .001). In the second group of CPs used by patients to co-construct new meanings during the therapeutic conversation, resignification referred to herself is the only one whose probability of occurrence is predicted by the interaction effect between personality style and the episode type (see Table 6). The second part of the hypothesis was confirmed: anaclitic patients are more likely to resignify contents referred to themselves during CEs (OR = 2.22, p = .015) than introjective patients, who use this CP more often during SEs (OR = 0.17, p = .003).

Finally, while it is true that patients use at least 4 CPs to show understanding, generate harmony, or provide feedback about certain contents, all of them are used with equal probability during the therapeutic conversation (see Table 6). The probability of occurrence of these CPs cannot be forecast using any of the predictor variables (Level-2 and Level-3), nor the interaction effect between those levels.

Predicting CPs from the Phase of the Therapeutic Process

All the CPs used by patients with the communicative intention of exploring, resignifying, and attuning, regardless of the kind of contents therapeutically worked on (cognitive, affective, or behavioral), as well as the references of those verbalizations (protagonists of therapeutic work), are used by patients during the first third of the therapy (initial phase) with the same probability as during the last two thirds of the process taken together (middle and final phases). Therefore, the probability of occurrence of such CPs cannot be predicted by observing the initial phase of the therapy. However, the probability that patients use more cognitive explorations during the last third of the therapy (final phase) can be predicted by their symptoms. Depressive patients are more likely to use this CP during the final phase (OR = 0.58, p = .037) than anxious patients. Patients were also observed to be more likely to use cognitive resignifications during the last phase of the therapy (OR = 0.73) compared to the first two thirds of the process taken together (initial and middle phases). In addition, introjective patients are more likely to use cognitive resignifications at the end of the therapy (OR = 0.40, p = .021) compared to anaclitic patients. Even though it was not an initial hypothesis, this result further confirms the aforementioned hypothesis 2.

Discussion

This findings presented in this article propose a view of therapeutic language which includes both the transmission of contents directly associated with the object of therapeutic work, but also the performance of actions by both participants when they speak. This twofold notion of verbal communication makes it possible to analyze therapeutic activity by identifying variable actions whereby both patients and therapists participate in the construction of psychological change (Valdés, 2012; Valdés, Dagnino et al., 2010; Valdés, Tomicic et al., 2010). This study focused on the existence of verbal micromarkers in the patients' speech, depending on whether they were therapeutically working on the construction of new meanings, or if they were experiencing a temporary halting of the change process during the session, characterized by an argumentative persistence in the patient's discourse that does not contribute to the objective of change. Furthermore, the probability of predicting those verbal micromarkers based on the patients' symptomatology and personality organization was also explored.

Communicative Actions are a relevant element in the psychotherapeutic process, because they make it possible to characterize the therapeutic dialog from the patients' and therapists' verbalizations. These actions are directly related with the object of therapeutic work, and do not only convey contents when speaking, but also construct a new reality upon the basis of language. In this sense, the TACS-1.0 has been developed considering parallel and non-inclusive dimensions of analysis, which make it possible to account for the complexity and multidimensionality of communicative interaction during the psychotherapeutic dialogue (Valdés, Tomicic et al., 2010). Previous studies have shown that TACS-1.0 is an analysis tool capable of identifying differences in the way both patients and therapists speak, allowing rigorous analysis in order to obtain information about the evolution of the verbal communication, the mechanisms, and the actions that produce change throughout the psychotherapeutic process (Valdés, 2012; Valdés, 2014; Valdés et al., 2011; Valdés et al., 2012). For example, it has been possible: (a) to account for the complementary or symmetrical nature of the therapeutic interaction, as well as the evolution of this relationship throughout the psychotherapeutic process; (b) to analyze therapeutic activity simultaneously in terms of its specificity (verbalizations which are more frequent in certain psychotherapy approaches and modalities) and its shared characteristics (verbalizations present in different types of psychotherapy); (c) to code patients' and therapists' verbalizations during relevant episodes of the session; and (d) to describe and monitor the characteristics of therapeutic work depending on the phase of therapy. However, this is the first time that patient-related variables are introduced to analyze the characteristics of their discourse, according to the symptomatology and personality organization they present.

The first question relates to the main differences between Change and Stuck Episodes with respect to the verbal micromarkers identified, regardless of the patients' symptomatology and personality organization, so as to determine whether there was any influence of these variables on the communicative actions used by patients during the therapeutic conversation in both episode types. A speaker's verbalization is characterized by a formal structure (Basic Form) with a communicative purpose (Communicative Intention) for working on a specific type of content (Domain), referred to the protagonist of that therapeutic work (Reference); also, sometimes a communicative or therapeutic resource (Technique) may be present to support the communicative purpose (Valdés et al., 2012). As expected, the episode type appeared to influence the verbalizations that patients use. During Change Episodes, patients display a greater tendency to admit as true what therapists say (agreement) and to co-construct and consolidate new meanings based on the contents provided by them (resignify). In contrast, during Stuck Episodes patients tend not to accept as true what therapists say (deny), while also failing to convey new contents, clarify them, or simply direct the therapist's attention towards certain aspects of the conversation (explore). In addition, patients verbalize contents belonging to the world of emotions (affective), many of which are related to their relationships outside of the session (reference to the relationship with a third party). This more extensive usage of deny by patients during Stuck Episodes may have been associated with the action of resisting the construction of new meanings, while the more frequent presence of agreement during Change Episodes has been deemed to reflect the use of verbal expressions to accept, maintain, or reinforce new meanings provided by therapists (Valdés, 2012).

An interesting finding was the predominance of affective contents during Stuck Episodes, that is, in those moments of the session with no co-construction of new meanings. Because affective and cognitive contents are always interacting during the patients' discourse, the verbal expression of emotional contents plays a central role when constructing new meanings. In this regard, even when the patients are not resignifying new meanings during Stuck Episodes, these periods of the session may be considered as a therapeutic space in which the therapist can delve into the patient's unconscious defenses that lead them to stagnate during the therapy using specific maladaptive patterns as a loop. The persistence of verbalizations related to the experience of negative basic emotions could be interpreted as a necessary condition to increase awareness of better cognitive or affective adaptive patterns during the construction of new meanings during Change Episodes. Facilitating the patient's emotional involvement during the therapeutic process appears to be a factor that fosters cognitive and behavioral changes (Castonguay, Goldfried, Wiser, Raue, & Hayes, 1996; Goldman, Greenberg, & Pos, 2005).

The second question relates to the main verbal micromarkers identified in terms of the patients' symptomatology and personality configurations. As mentioned above, differences in personality styles are determined in part by the dimension to which an individual gives priority: interpersonal relatedness or self-definition. However, in addition, patients with elevated levels of dependency may become depressed in response to stressful interpersonal events such as rejection and loss, while patients with elevated levels of self-criticism may become depressed in response to events threatening the self, such as failure. The results of this study were consistent with previous empirical and theoretical assumptions about the probability of predicting specific verbal micromarkers for each type of patient. As expected, anaclitic patients tend to use more verbalizations for asking their therapists for more feedback as a way to be understood by them (attune), but primarily to work on contents referred to others during the session (referred to a third party). This result is consistent with the fact that anaclitic patients are always desperately concerned about issues of trust, closeness, and the dependability of others, as well as about their own capacity to love and express affection. It is not a surprise that anaclitic patients use these verbal micromarkers, which express their exaggerated anxiety about establishing and maintaining interpersonal relationships. The patients' need to be cared for, loved, and protected, along with the permanent fear of being abandoned, configure a pattern that can be used to relate with their partners out of the session, but also with their therapists within the session.

In contrast, as we expected, introjective patients tend to use more resignifications in order to co-construct and/or consolidate new meanings; in addition, they use more verbalizations for working on contents in which the protagonist of the therapeutic work is not a person, but a reserved and distant position (neutral reference). This result is consistent with the fact that these patients share an exaggerated and distorted preoccupation with establishing and maintaining a definition of the self, at the expense of establishing meaningful interpersonal relationships. The cognitive processes in patients with an introjective configuration are more fully developed, and have a greater potential for the development of logical thought. They think primarily in sequential and linguistic terms and emphasize the analysis or the critical dissection of details and the juxtaposition and comparison of part properties (Blatt, 2008). Introjective patients use resignifications in order to note and emphasize differences and contradictions between the contents worked on during the therapeutic conversation, but primarily in the service of differentiation and self-definition. They have an ideational orientation; at the same time, they value reason over emotions as a way to be judgmental and critical of self.

Additionally, like anaclitic patients, introjective patients resignify new contents during Change Episodes, but they also use this communicative intention during Stuck Episodes, which was interpreted as a verbal mechanism aimed at evaluating and contrasting alternatives on their own, but also as a way to influence therapists to accept and conform to their views. It has been theoretically argued that introjective patients have an acute, intense, and narrow cognitive functioning, based on relevant and rigid ideas focused on technical details, with an emphasis on logical sequential thought and issues of causality (Blatt, 2008; Blatt & Blass, 1996). Previous studies have shown that verbalizations acquire a specific configuration with certain characteristics which depend on the way in which all these dimensions fit together during each speaking turn of therapeutic dialog. Such configurations are termed Communicative Patterns (CPs), and are used by patients and therapists to work on various contents and influence each other during the conversation (Valdés et al., 2012). The present study confirms this, since introjective patients not only resignify more contents during Stuck Episodes, but also resignify more cognitive contents as a pattern (cognitive resignification) during those periods of the session characterized by a temporary halting of the change process, with the persistence of reasons and arguments that do not allow for the construction of new meanings. In addition, they resignify more contents related to themselves as protagonists of the therapeutic work (resignification referred to themselves), that is, as a primary preoccupation with their self-definition. However, the opposite was observed in the case of anaclitic patients, who use this communicative pattern more often during Change Episodes, that is, they use it to facilitate changes in meanings, which also could be interpreted by the therapist as changes in the structural organization of their mental subjective theories or mental representations (e.g., Blatt, 2008; Blatt, Stayner, Auerbach, & Behrends, 1996).

As mentioned before, sometimes speakers use communicative or therapeutic resources to support their communicative intention (when they are exploring, attuning, or resignifying) during a verbalization. Introjective patients use therapeutic techniques (e.g., confrontation and interpretation) more often during Stuck Episodes, whereas they use more communicative techniques (e.g., argumentation and narration) during Change Episodes. It should be mentioned that introjective patients tend to use counteractive rather than avoidant defenses to confront or intellectualize their vulnerability to feelings of failure, inferiority, and guilt, in an attempt to defend their own ideas and preserve a consolidated sense of self. Based on that, the therapeutic relationship may be considered by introjective patients as a potentially dangerous situation, in which failure is experienced as a threat that others will take advantage of and humiliate them. It should be emphasized that they are self-critical individuals who are always trying to maintain their autonomy and control to generate stressful events involving rejection and confrontation (Blatt et al., 1976; Dunkley & Blankstein, 2000; Priel & Shahar, 2000; Zuroff & Duncan, 1999). It is for this reason that self-criticism functions as a primary instigator of depressive symptoms: it generates a risk-related social environment which interferes with close relationships (Shahar, Blatt, Zuroff, & Pilkonis, 2003) and predicts interpersonal tensions and ruptures (Priel & Shahar, 2000; Vettese & Mongrain, 2001).

The last question that guided the present study relates to the behavior of Communicative Actions and Communicative Patterns during the initial and final phases of the therapy. The results showed that the phase of the therapy predicts the probability of some communicative actions being used, but only when the patient's symptomatology and personality style are considered. As mentioned before, the patients' verbalizations used to ask for feedback or to be understood by their therapist (attuning) were not only more likely in the group with depressive symptoms; also, their probability of occurrence was observed to depend on the phase of therapy. Depressive patients use this communicative action less frequently during the initial phase of therapy, although they apply it more during the final phase. This result is consistent with the assumption that therapeutic work on specific contents is not only connected with certain emotional expressions and the construction of new meanings, but also with the patients' feeling of being understood by their therapists (Bänninger-Huber & Widmer, 1999; Popp-Baier, 2001). In other words, it is not enough to work on new perspectives using complex interventions during the therapeutic conversation, because patients increasingly demand moments of meeting or empathic understanding (Ávila, 2005; Gabbard et al., 1994; Mitchell & Black, 2004; Rubino, Barker, Roth, & Fearon, 2000; Stern, 2004), in which the use of verbalizations in order to attune may reflect a depressive patient's need of the emotional empathy required for working at a therapeutically deeper level - to have a more relevant impact on therapeutic outcome, which is also strong enough to persist for a longer period than in interventions that only involve the cognitive domain (Orlinsky & Howard, 1987).

Closely related to the previous point is the question of how the probability of working on affective contents during the final phase of therapy is also influenced by the patient's symptomatology. Depressive patients are more likely to work on affective contents during the final phase of therapy, compared to what happens during the first two thirds of the process. This result was predictable if we consider that patients' subjective emotional experience changes over the course of the psychotherapeutic process, so that better outcomes are associated not only with a decrease in the proportion of negative emotions, but also with an increase in emotional variability (Leising, Rudolf, Oberbracht, & Grande, 2004). The therapeutic conversation is an activity aimed at the reconstruction of patients' experience, which allows them not only to focus on constructing new meanings aided by the therapist's empathy and assistance, but also on narrating their own affective experiences in order to attain a more profound understanding of themselves.

The important role of therapeutic work at an affective level is clear to judge from this study; however, most of the work is done using verbalizations in order to resignify new meanings during the therapeutic conversation. Thus, patients tend to use more resignifications during the final phase of the therapeutic process than in the initial one. If psychotherapeutic change is understood as a modification at a representational level (Krause et al., 2007), it is not a surprise that patients tend to perform more cognitive resignifications throughout the process. The patients' discourse includes more questioning of elements, more establishment of relationships, and more offering or approval of new meanings for certain contents as therapy progresses, which could be interpreted as changes in their cognitive organization observable at a communicative level. In addition, it was possible to demonstrate that introjective patients use more cognitive resignifications towards the end of the therapy, compared to anaclitic patients. As expected, introjective patients are more responsive to interpretive interventions during the therapy process due to their primarily overideational orientation. Therefore, they are mainly focused on exploring and interpreting aspects of the treatment and the new meanings that they constructed, instead of paying attention to more relational aspects.

Implications for Clinical Practice

The Therapeutic Activity Coding System (TACS-1.0) has proven to be a tool capable of accounting for the complexity and multidimensionality of patients' verbalizations during the psychotherapeutic conversation, providing additional support to differentiate the discourse of anaclitic and introjective patients as a clinically important distinction that could be used by their therapists to understand their experiences based on their coherent verbal expression, in order to facilitate an effective therapeutic work by conducting a differential treatment process (Blatt, 1992; Blatt, 2008; Blatt et al., 1996). In this sense, therapists must be able to identify certain communicative patterns that seem to play a central role in patients' change, properly noting relevant characteristics of patients, dependent on their personality style, that facilitate a further understanding of the factors and mechanisms that contribute to therapeutic change. This study used a complex methodology to demonstrate that anaclitic patients tend to use more verbalizations for requesting the emotional empathy they need for developing a therapeutic relationship that allows them to work therapeutically, whereas introjective patients tend to use verbalizations that facilitate explorations and resignifications accompanied by a distant and emotionally controlled engagement (Fonagy et al., 1996; Gabbard et al., 1994).

Besides their implications for clinical practice, the results offer empirical support that can be used by therapists to develop and maintain an appropriate therapeutic relationship, using more interpersonal or more interpretive interventions depending on the specific concerns and conflicts present in each personality organization. Even if the therapeutic goals are the same, the focus is different in each case, that is, sometimes it will be necessary to enable patients to develop more mature levels of interpersonal relatedness in order to pave the way for future insights and self-understandings (anaclitic), but in other occasions it will be necessary to integrate a self-definition in order to facilitate the development of a suitable therapeutic relationship (introjective) (Blatt & Blass, 1996; Fonagy, Gergely, Jurist, & Target, 2002).

Study Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study included the development of a systematic methodology which considered several reliability studies with raters who have a vast clinical experience to identify the patients' symptomatology and personality styles using the Observation Guideline. Even when a level of expertise is required to code relevant segments within the therapeutic sessions, the SCAT-1.0 has proven to be a system that can be easily used to classify the verbal expressions in order to characterize the evolution of the verbal communication, the mechanisms, and the actions that produce the patient's change throughout the psychotherapeutic process. But the most important thing is that it was not constructed based on a specific psychotherapeutic model or a particular intervention. On the contrary, it was developed in order to study patient-therapist interaction in psychotherapies of different approaches and modes. The generic nature of the system makes it possible to analyze therapeutic activity simultaneously in terms of its specificity (for example, the analysis of the Communicative Actions which may be more frequent in certain psychotherapy types) and its shared characteristics (for instance, the analysis of Communicative Actions present in different types of psychotherapy).

Assuming that the predictor variables were at different hierarchical levels, a complex form of ordinary least squares regression (HLM) was used to analyze variance in our outcome variables. In this sense, the analysis system is fully adjusted to a design that we think is unique in its focus on describing the therapeutic conversation at different levels, respecting the nested nature of the data.