Introduction

Linezolid is a synthetic antibiotic within the oxazolidinone class, with activity against gram positive bacteria and mycobacteria. Its antibacterial spectrum includes methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus1. It is approved for use in nosocomial pneumonia, community-acquired pneumonia and skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI), and it has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of osteoarticular and prosthetic materials infections2. On the other hand, according to the classification by the World Health Organization, it belongs to Group 5 of anti-tuberculosis agents used as 2nd line in multi-drug resistant tuberculosis, caused by multi-drug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and extensively-drug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis (XDR-TB)3.

Linezolid is an antibiotic with a good safety profile, though adverse effects have been described, such as: diarrhea, vomiting, headache, anaemia, thrombocytopenia, lactic acidosis, and peripheral and optic neuropathy. In clinical practice, it has been used for complicated infections requiring prolonged treatment. However, its safety in > 28-day treatments has not been systematically evaluated in controlled clinical trials. Overall, optic and peripheral neuropathies are side effects observed in prolonged treatments.

Optic neuropathy is defined as a clinical syndrome characterized by blurry vision, loss of visual acuity, damage in the papillomacular bundle, presence of central or ketocentral scotoma in the range of vision, and alteration of colors4.

Linezolid acts by inhibiting the synthesis of bacterial proteins through the specific binding of the ribosomal sub-unit 50S. This blockade has almost no impact on mammal proteins, but with prolonged treatments it can interfere in the protein synthesis of mitochondria, causing its dysfunction5. The optic nerve is the hypothesis supporting the etiology of optic neuropathy alteration of the mitochondrial oxidative metabolism in the by linezolid.

Some of the outstanding causes that can originate optic neuropathy are: chemotherapy agents such as ethambutol, isoniazid, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, anti-tumor necrosis factor agents (anti-TNFs), toxic agents such as methanol and mercury, alcoholism and smoking, as well as nutritional deficiencies, such as lack of vitamin B12, thiamine, and folic acid6.

There are limited data on the frequency of optic neuropathy associated with linezolid. Cohort studies and case series described a relatively low prevalence, ranging between 1.3% and 3.3%7-9. However, in a meta-analysis conducted in 2012, it was observed that there was a 13.2% increase in prevalence10; and most recently, in 2015, an 8%11.

The objective of the present review was to collect all described cases of optic neuropathy associated with linezolid that had been published in literature, and to analyze the demographical, clinical and ophthalmological characteristics of this group of patients.

Methods

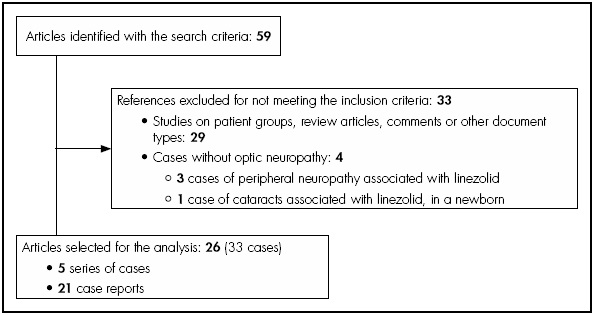

A qualitative systematic review was conducted on cases of optic neuropathy associated with linezolid, following the guidelines established by PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses). The analysis included patients from case reports or series of cases from original articles. The search was conducted using the following data-bases: PubMed-Medline, Embase and ScienceDirect, between September, 2002 and April, 2018. The terms of search were “linezolid” and “optic neuropathy”, conducted for “All field”. The search equation for Medline was: (linezolid(MeSH Terms)) AND optic neuropathy(MeSH Terms). Titles and abstracts of the articles were used for the process of selection; articles in Spanish, English, French and German were analyzed. Figure 1 shows the flow diagram for case selection.

Demographical and clinical characteristics of each patient were collected and analyzed: age, gender, background, concomitant treatment, type of infection and bacteria involved, daily dose of linezolid and total accumulated dose, time of exposure to linezolid until the onset of symptoms and time of exposure until withdrawal, treatment for optic neuropathy and its efficacy, presence of other adverse effects attributed to linezolid, and time of follow-up since antibiotic withdrawal. Clinical ophthalmological characteristics were also collected and analyzed: presence of blurry vision, type of ocular alteration: bilateral or unilateral, presence of color alteration, visual acuity (VA), type of alteration in ocular fundus and in the range of vision.

Descriptive analysis was conducted through the SPSS program (version 20.0). Qualitative variables were expressed in percentages, and quantitative variables in mean value (± standard deviation).

Results

According to the search criteria, 59 studies were obtained in total. During the selection process, 33 articles were excluded, and the analysis included 33 cases in total of optic neuropathy associated with linezolid, from 26 independent articles (Figure 1).

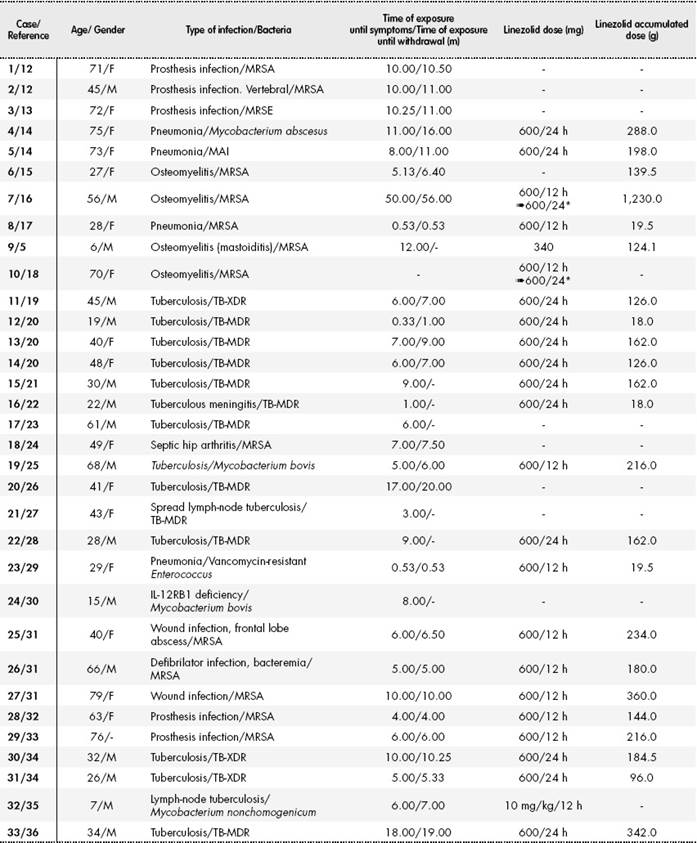

Table 1 shows the clinical and demographical characteristics of these 33 cases: 16 out of 32 (50%) patients were female, and two were pediatric patients. Their mean age was 44.97 ± 21.40 years (range: 6-79). The duration of treatment with linezolid until the onset of symptoms was > 28 days, in 29 (90.6%) out of 32 documented cases. The mean time of exposure until the onset of symptoms and the mean time of exposure until withdrawal of linezolid was 8.5 ± 8.6 months (range: 0.33-50) and 10.1 ± 10.3 months (range: 0.53-56) respectively. The mean time of follow-up was 5.6 ± 5.0 months (range: 1-23). Fourteen (14) patients received linezolid ≤ 600 mg/24 h (including the two pediatric patients), eight received 600 mg/12 h and two initiated treatment at 600 mg/12 h and then were adjusted to 600 mg/24 h. In the rest of cases, the dose used was not available. The mean dose accumulated was 201.6 ± 222.9 g (range: 18-1,230).

Table 1. Demographical and clinical characteristics of the 33 cases of optic neuropathy associated with linezolid14,16, 18, 19, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 31, 32, 33, 34, 36

F: female; M: male; m= months; MAI: Mycobacterium avium intracelulare; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MRSE: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis; TB-MDR: multi-drug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis; TB-XDR: extensively drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. *Treatment initiation at 1,200 mg/24 h and dose reduction at 600 mg/24 h.

In 30 of the 33 (90.9%) patients, VA loss was observed; 28 (93.3%) of the 30 documented cases presented bilateral VA alteration, and two presented unilateral VA alteration. 19 (82.7%) of the 23 documented cases suffered color alteration. In terms of ocular fundus examination, optic disc alterations were detected in 23 (79.3%) of the 29 cases documented. In the range of vision examination, defects were collected in 22 (95.7%) of the 23 patients documented, including: seven central scotomas, seven ketocentral scotomas, two with peripheral constrictions, and one with generalized field involvement.

Linezolid was withdrawn in all cases, once diagnosis had been confirmed, and clinical improvement was observed in 31 of the 33 (93.9%) patients. In one case there was symptom worsening, and another patient presented total and irreversible loss of vision, regardless of linezolid discontinuation. In one patient, linezolid was reinitiated with a subsequent final withdrawal, due to a rapid relapse of symptomatology.

In five patients, treatment with corticosteroids was initiated; three of them received systemic corticosteroids, one received ophthalmic topical corticosteroids, and one received both. Clinical improvement was observed in two patients with the administration of corticosteroids, once linezolid had been withdrawn, while no satisfactory clinical response was reached in the other three, but there was a worsening in neuropathy before linezolid withdrawal, and one patient even presented total and irreversible vision loss, as already mentioned.

In 17 (48.5%) cases, symptoms compatible with peripheral neuropathy were observed, while only five (14.3%) were confirmed through electrodiagnosis. Only four of 13 (30.8%) cases presented symptom recovery, one of them partial and the other slow and progressive.

Two patients suffered lactic acid elevation, and one of them presented also hepatic encephalopathy, myopathy and renal impairment. In one case, myelosuppression secondary to linezolid was described (anaemia and neutropenia).

Regarding nutritional status, one case presented vitamin B12 deficiency associated with chronic gastritis, and another one had a mild deficiency of folic acid.

On the other hand, three cases received concomitant treatment with ethambutol, two with capreomycin, seven with quinolones, two with isoniazid, and one received previous treatment with vincristine.

Discussion

The increase in the incidence of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis in the past two decades has represented a setback for the control of the tuberculosis epidemics at world level, and forced to use second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs, such as linezolid. Treatment duration has led to an increase in adverse effects associated with prolonged exposure, such as optic neuropathy. In our review, we have collected and analyzed 33 cases in total of optic neuropathy associated with linezolid; their main infections were caused by multi-drug resistant TB, among others.

Optic neuropathy secondary to linezolid is associated with its prolonged use. In the meta-analysis by Zhang et al., with 23 optic and 79 peripheral neuropathies, the duration of treatment with linezolid was > 5 months11. In other study on a retrospective cohort with five optic neuropathy cases, the time of linezolid administration was > 7 months in all cases, and the mean time of administration was 10 months37. According to the results mentioned, in our study the mean treatment duration was 10 months. On the other hand, it is worth highlighting the presence of three cases of optic neuropathy associated with short treatments < 28 days17,20,29.

The dose ≤ 600 mg/24 h vs. ≥ 600 mg/24 h, in the meta-analysis by Sotgiu et al., reduced the frequency of optic neuropathy and other adverse effects, without compromising efficacy in patients with multi-drug resistant tuberculosis10. Subsequently, in the previously discussed meta-analysis by Zhang, the dosing ≤ 600 mg/24 h did not show a reduction in optic neuropathy in this type of patients11. In our study, we found up to 12 cases of adult patients with a 600 mg/24 h initial dose, who experienced optic neuropathy regardless of the reduced dose, which shows the need for ophthalmological follow-up and monitoring for all patients with prolonged treatments, regardless of the dose used.

Optic neuropathy associated with linezolid is a reversible process in most cases, and there is symptom improvement once the antibiotic has been withdrawn. In our review, only one case suffered worsening regardless of linezolid withdrawal20, and another case suffered a total loss of vision17. On the other hand, peripheral neuropathy is usually an irreversible process, where no clinical benefit is observed regardless of antibiotic withdrawal38. Only four cases compatible with peripheral neuropathy experienced improvement in our study21,25,28,30.

The efficacy of corticosteroid treatment is a controversial matter. In their study, Mehta et al. observed clinical improvement, both in patients treated with corticosteroids and in those not treated37. In our review, corticosteroid administration was beneficial in two cases12,13, while three experienced a worsening in their neuropathy15,17,35. Therefore, more studies are necessary, on a wider population, in order to reach final conclusions about the benefit of corticosteroids.

Finally, it is worth highlighting the low incidence of myelotoxicity (anemia and thrombocytopenia) associated with linezolid in our series, with only one patient documented. This can be explained by a difference in mechanism, regarding mitochondrial inhibition in optic neuropathy.

Our review presents some limitations. Firstly, there is a small sample size, and we have evaluated cases from articles with potential publication bias. Secondly, the level of detail provided in each case was not homogeneous and, therefore, was subject to a certain level of data interpretation. Regardless of limitations, we believe that this review will provide useful information.

In conclusion, optic neuropathy is a complication associated with the prolonged use of linezolid, regardless of the dose received, and reversible in most cases. The increasing use of linezolid in regimens for treatment of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis and complicated infections caused by resistant gram positive bacteria, has led to an increase in the incidence of optic neuropathy associated with the prolonged use of linezolid. Therefore, it is important to conduct multidisciplinary follow-up for patients on long treatment regimens > 28 days, particularly in those with visual alterations. It would be convenient to conduct an exhaustive ophthalmological examination (to evaluate visual acuity, range of vision, color vision, and ocular fundus) in order to be able to conduct an early diagnosis of optic neuropathy, and therefore an early withdrawal of linezolid.

texto em

texto em