Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Psychosocial Intervention

versão On-line ISSN 2173-4712versão impressa ISSN 1132-0559

Psychosocial Intervention vol.23 no.2 Madrid Ago. 2014

https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psi.2014.07.004

Acculturation and adjustment of elderly émigrés from the former Soviet Union: A life domains perspective

Aculturación y adaptación de personas mayores exiliadas de la antigua Unión Soviética: Una perspectiva desde las facetas de la vida

Ana G. Genkovaa, Edison J. Tricketta, Dina Birmana y Andrey Vinokurovb

a University of Illinois at Chicago, U.S.A

b Optimal Solutions Group, U.S.A

ABSTRACT

Former Soviet émigrés in the United States are on average older than other immigrant groups, with adults over 65 comprising a large portion of the Russian-speaking population. Despite known risks associated with old-age migration, however, researchers and providers have underestimated adjustment difficulties for Russian-speaking elderly in U.S. These older adults tend to acquire a new culture with difficulty and remain highly oriented towards their heritage culture. However, limited research examines how acculturation to both the culture of origin and the host culture contributes to wellbeing for this immigrant group. This study assesses the adaptive value of host and heritage acculturation across several domains in the lives of older émigrés from the former Soviet Union resettled in the Baltimore and Washington, DC areas in the United States. Acculturation level with respect to both host and heritage culture was measured with the Language, Identity, and Behavior Scale (LIB; Birman & Trickett, 2001) and used to predict psychological, family, social, and medical care adjustment outcomes. Results suggest that acculturation to the host or heritage culture has different functions depending on life domain. Particularly, high American acculturation contributed to better adjustment in the psychological, family, and social domains. Heritage acculturation was associated with better outcomes in the social domain and had mixed effects for psychological adjustment. Theoretical implications highlight the importance of evaluating multiple life domains of adapting through a bilinear acculturation model for the understudied population of elderly immigrants.

Keywords: Immigrants. Elderly. Refugees. Acculturation. Life domains Émigrés

RESUMEN

Las personas ex-soviéticas que se exiliaron a los EE.UU. tienen una media de edad superior a la de otros grupos de inmigrantes; entre ellas, los adultos que superan los 65 años suponen un gran porcentaje de la población ruso parlante. A pesar de que se conocen los riesgos asociados con la inmigración de personas mayores, los investigadores y agentes que prestan servicios han subestimado las dificultades de adaptación de las personas mayores ruso parlantes en los EE.UU. A estas personas les cuesta adquirir una nueva cultura y siguen muy orientados hacia su cultura de origen. No obstante, no abunda la investigación que analice de qué mane-ra contribuye al bienestar de este grupo de inmigrantes la aculturación tanto en la cultura de origen como en la cultura de acogida. Este estudio analiza el valor adaptativo de la aculturación de origen y de acogida en diversas facetas de la vida de las personas de más edad que se exiliaron de la antigua Unión Soviética y se establecieron en EE.UU. en zonas de Baltimore y Washington DC. El nivel de aculturación tanto en la cultura de acogida como en la de origen se ha medido con la Escala de Idioma, Identidad y Comportamiento (LIB; Birman & Trickett, 2001), que se utilizó para predecir el grado de ajuste psicológico, familiar, social y sanitario. Los resultados indican que la asimilación de la cultura de acogida o de origen tiene funciones diferentes dependiendo de la faceta de la vida. En concreto una elevada aculturación estadounidense contribuía a una mejor adaptación en las facetas psicológica, familiar y social. La aculturación de origen se asociaba a mejores resultados en la faceta social aunque eran contradictorios en el ajuste psicológico. Las implicaciones teóricas destacan la importancia de evaluar las distintas facetas de la vida en la adaptación a un modelo de aculturación bilineal en el caso de la población de inmigrantes mayores, escasamente estudiada.

Palabras clave: Inmigrantes: Personas mayores: Refugiados: Aculturación: Facetas de la vida Exiliados

Socio-political events in recent decades drove large numbers of former Soviet Union citizens out of their homelands. Over half a million Russian-speaking émigrés resettled in the U.S. fleeing ethnic and religious persecution (Klinger, 2007; Polyakova & Pacquiao, 2006). Many extended families emigrated together, bringing aging relatives along. Consequently, adults over 65 comprise a large proportion of the Russian-speaking population in the U.S. (Polyakova & Pacquiao, 2006). Despite known risks associated with migration at an older age, however, researchers and providers have underestimated adjustment difficulties for Russian-speaking elderly in U.S. (Kim-Goh, 2006).

In some respects, Russian-speaking elders enjoy privileges inaccessible to other migrant groups (Birman, Persky, & Chan, 2010). Russian-speaking Jews, who comprise a large portion of the Russian-speaking population in the U.S., have political refugee status that grants them legal and social safeguards (Klinger, 2007). Further, although an oppressed minority group in the former Soviet Union, upon arriving into the U.S., Soviet Jews are perceived as part of the White majority (Persky & Birman, 2005), and may experience benefits relative to other immigrants. Additionally, most Russian-speaking immigrants come with a high formal educational background and professional qualifications, which may provide socio-economic advantages (Klinger, 2007). At the same time, Russian-speaking elderly undergo the stressors of the immigration experience with the added vulnerability related to their age of migration and difficulties learning the new language and culture. In addition, although they benefit from being perceived as "White" in the US context, they also experience discrimination and anti-immigrant sentiment prevalent in the larger US society (Vinokurov, 2001). These factors may impact the availability and quality of social resources linked to wellbeing (García-Ramírez, de la Mata, Paloma, & Hernández-Plaza, 2011; Prilleltensky, 2012).

Past research with Russian-speaking elderly has focused primarily on cultural resources with respect to the receiving culture. Specifically, studies have linked English language ability or time in the U.S. to better overall adaptation (Tran, Sung, & Huynh-Hohnbaum, 2008; Tsytsarev & Krichmar, 2000). However, others have suggested that older immigrants acquire a new language with difficulty and maintain their heritage culture for decades after resettlement (Jang, Kim, Chiriboga, & King-Kallimanis, 2007; Miller, Wang, Szalacha, & Sorokin, 2009). Therefore, we examine how both host and heritage cultural changes can facilitate or impair adjustment. We refer to these changes as acculturation to the host or heritage culture (Birman & Simon, 2013).

The adaptive value of acculturation to either culture depends on the context of adjustment. The resettlement process involves an "ecological transition" that requires adjusting to a "new physical and socio-cultural context, ... important changes in prevailing norms and values, the social position of individuals, their labor and economic situation, their network of interpersonal relationships and their general living conditions (Hernández-Plaza, García-Ramírez, Camacho, & Paloma, 2010, p. 237). From this perspective, adjusting to a new culture means functioning across spheres of daily life that present different goals, constraints, and opportunities. In addition, for immigrants, these spheres of life also differ culturally, as some exert constraints and opportunities related to the immigrants' heritage culture, and others to the larger surrounding culture of the host society (Birman, Simon, Chan, & Tran, 2014). Accordingly, in this study we apply an ecology-of-lives perspective to examine how acculturation to the host or heritage culture affects adjustment in several domains of the lives of Russian-speaking elderly (Trickett, 2009). Past studies have shown that immigrant adolescents and working-age adults rely on different cultural resources depending on the life domain they have to navigate (Arends-Tóth & van de Vijver, 2004; Birman et al., 2014; Birman, Trickett, & Vinokurov, 2002). However, research has not focused on the adaptation of older adults in their daily lives.

Interviews with older former Soviets have revealed that social networks, the family, and medical care are central domains in their lives (Ucko, 1986; Vinokurov, 2001). Moving to another country involves changes to all of these domains. The transition severs lifelong social ties and changes family dynamics and medical care in a time of life when social isolation and frail health present the greatest risks to wellbeing (Litwin, 1997; Treas & Mazumdar, 2002; Ucko, 1986). This study will explore how host and heritage acculturation are differentially related to adjustment with respect to these domains. In addition, we assess the direct relationship between host and heritage acculturation and psychological wellbeing.

A Life Domains Approach to Acculturation and Adaptation

A life domain perspective allows us to empirically assess the significance of varied acculturative strategies for individuals living in and adapting to multiple cultural contexts. In the United States, early models of acculturation reflected the dominant cultural narrative of a "melting pot." Norms, structures, and policies promoted assimilation (i.e., adopting the new culture while discarding the heritage culture) as the encouraged outcome of the acculturation process (Birman, 1994). Such perspective fails to account for discrimination against people of color who cannot become fully accepted in the larger society through assimilation. More recently, biculturalism and the parallel policies of social integration have been promoted as the optimal acculturation strategy (García-Ramírez et al., 2011). These policies encourage immigrants to acquire the new culture while maintaining attachments to their culture of origin. Berry's (1980) four-fold model of acculturation has served as the grounding framework establishing the value of biculturalism as an adaptive strategy. Nevertheless, empirical studies have provided mixed evidence regarding which acculturative styles facilitate psychosocial adaptation or pose barriers to wellbeing (Birman & Simon, 2013; Escobar & Vega, 2000; Rudmin, 2003). The resulting discussion in the acculturation literature has raised questions about the various contextual influences on the adaptation process (Birman & Simon, 2013; García-Ramírez et al., 2011; Prilleltensky, 2008). Consequently, research is now focusing on these contextual factors.

At the national level both biculturalism and social integration have considerable merit as the leading ideologies. At the individual or group levels, however, these ideologies may be oppressive to immigrants perceived to adopt alternative strategies (e.g. separatism, assimilation) rather than to adhere to the preferred one (i.e., biculturalism). However, acculturation strategy is not a personal choice, but the result of formal and informal societal pressures and factors such as age of migration, cultural differences, and migration causes (Liebkind & Jasinskaja-Lahti, 2000). For example, children migrating with families do not make the choice to resettle in another country. Additionally, the process of acquiring the new language and culture markedly differs for immigrants who arrive as children, adults, or elderly (Birman & Trickett, 2001).

The terms integration and biculturalism represent what Bronfenbrenner (1988) calls "social addresses", labels that have considerable heuristic value but do not clarify the specific life circumstances influencing acculturating groups in specific ecologies. For example, when faced with racism, minority youth may reject the dominant culture and identify with the culture of origin (Portes & Zhou, 1993). This strategy is considered separatism in Berry's (1980) model, but may be the most adaptive strategy for resisting oppression.

Acculturative contexts encompass multiple ecological levels as well as the dynamic interactions between them (García-Ramírez et al., 2011; Prilleltensky, 2008). The life domains approach differentiates the context of the acculturating individual across salient life areas such as school and home for adolescents (Birman, 1998) and family and work for adults (Birman et al., 2014). For immigrants, whose lives involve two cultures, these life domains vary in terms of the acculturative demands they exert in immigrants' lives (Birman, Trickett, & Buchanan, 2005; Trickett & Formoso, 2008). Therefore, each life domain may require different acculturative strategy. For example, former Soviet elderly may use the heritage culture, the host culture, or both to successfully meet daily needs. Consequently, the most adaptive acculturation strategy may depend on the specific life domain considered. This study aims to contribute to the literature by identifying a range of ways of acculturating considered adaptive for different people in different circumstances.

In this study, we focus on the acculturating elderly because they immigrate under different circumstances than children or working-age adults. The term acculturation, defined as changes occurring as a result of cultural contact, applies most readily to working age adults, but does not describe differences across the lifespan (Birman & Simon, 2013). For example, for children acculturation involves not only changes, but also continued development, and overlaps with the processes of enculturation and socialization. Late in life the process entails different goals. Elderly populations generally leave their homeland in order to remain close to children and grandchildren, with little interest in forming new social identities, engaging in transformative action, or even entering the workforce (Treas & Mazumdar, 2002; Tsytsarev & Krichmar, 2000). Given their immigration motives, elders' successful adaptation more likely depends on acquiring the cultural resources to address day-to-day needs. Therefore, we examine subjective wellbeing across multiple life domains that are situated within interpersonal, communal, and societal contexts of resettlement (Prilleltensky, 2012).

In order to understand the cultural resources that facilitate or hinder wellbeing across domains, we use a continuous scale that measures the extent of host and heritage acculturation in the cultural dimensions of language, identity, and behavior (LIB; Birman & Trickett, 2001). Host and heritage acculturation have been shown to be independent processes for Russian-speaking elderly immigrants (Miller, Wang et al., 2009). Therefore, we use an orthogonal measure to capture how acculturation to each culture affects wellbeing.

In this study we assess elders' adaptation through a lie domains perspective previously applied only to working-age adults and adolescents. Research these younger groups has shown that host and heritage acculturation provide culture-specific resources with varying usefulness for each life domain. Specifically, Turkish adults in the Netherlands indicated higher value for Dutch culture in public life domains, such as education, media, and government policy, and regarded Turkish culture more highly in private domains, including family life and religious celebrations (Arends-Tóth & van de Vijver, 2004). Similarly, host and heritage acculturation predicted different domains-specific outcomes for Vietnamese (Nguyen, Messé, & Stollak, 1999) and former Soviet (Birman et al., 2002) adolescents and adults (Birman et al., 2014) in the United States. We build on previous work by extending the life domains perspective to elderly immigrants.

Acculturation and Psychological Wellbeing

The most frequently studied outcome of the relationship between acculturation and adaptation for older adults encompasses overall psychological wellbeing (Nguyen et al., 1999; Swindle & Moos, 1992; Vinokurov, Trickett, & Birman, 2002). Although not a life domain, we include overall assessment of wellbeing in the present study to understand how cultural resources directly relate to subjective psychological wellbeing, thus expanding the present literature (Prilleltensky, 2012).

Across varied ethnic groups, older immigrants face the greatest risks of poor psychological adaptation (Kim-Goh, 2006; Ron, 2001; Tran et al., 2008; Vinokurov, 2001; Wrobel, Farrag, & Hymes, 2009; Zamanian, Thackrey, Brown, Lassman, & Blanchard, 1992). In reaction to differences between the culture of origin and resettlement, elders experience psychological distress characterized by a combination of psychological symptoms and physical complains (Krause & Golderhar, 1992; Ritsner, Modai, & Ponizovsky, 2000; Tsytsarev & Krichmar, 2000). Demographic characteristics also relate to psychological wellbeing for older adults. Women report greater adjustment difficulty than men (Shemirani & O'Connor, 2006), whereas married, highly educated elders experience fewer symptoms (Fitzpatrick & Freed, 2000; Jang et al., 2007).

Acculturation patterns, however, are related to both positive and negative indicators of psychological wellbeing (Yoon et al., 2013). Some studies suggest that host acculturation is related to decreased negative indicators, such as distress. For example, Latin American and Korean elders acculturated to the host culture were found to suffer fewer mental and physical symptoms of distress (Jang et al., 2007; Kraus & Goldenhar, 1992). In another study, former Soviet elderly who spoke the local language adjusted with less difficulty than the ones who did not (Tran et al., 2008). Therefore, host acculturation may provide cultural resources that elders need to function in a new country, reducing distress in the adjustment process.

With a few exceptions, studies with elderly immigrants have not measured heritage acculturation, so we know little about how it affects distress. For elderly Muslim immigrants, heritage acculturation related to more depressive symptoms (Abu-Bader, Tirmazi, & Ross-Sheriff, 2011), but this may not apply to Russian-speaking émigrés, who are White and may be perceived by others as part of the dominant U.S. culture aside from cultural and linguistic differences (Birman et al., 2010). Thus, the bilinear acculturation measure used in this study can indicate whether and how distress is associated with heritage acculturation.

Unlike distress, life satisfaction is a positive indicator of psychological wellbeing that measures a different aspect of adjustment (Yoon et al., 2013). Studies find that host and heritage acculturation both predict indicators of positive adaptation, including satisfaction with life (Yoon et al., 2013). In many cases, however, scales do not measure host and heritage acculturation independently. Instead, participants are categorized into one of the four acculturative styles within Berry's (1980) paradigm. This methodology has produced inconsistent results (Rudmin & Ahmadzadeh, 2001). For example, in one study all three acculturation categories of assimilation, integration, and separation predicted greater life satisfaction, leaving unclear the independent effects of the host and heritage cultures (van Selm, Sam, & van Oudenhoven, 1997). Because overall life satisfaction encompasses multiple aspects of people's lives, it is likely that both host and heritage acculturation relate to greater satisfaction. For example, host acculturation may contribute to higher life satisfaction through increased self-sufficiency in the new culture and heritage acculturation through positive relationships with the family and the Russian-speaking community (Katz, 2009; Litwin, 1997). The present study presents preliminary data on this issue.

Another wellbeing indicator that former Soviet elders frequently report is alienation from the host culture (Birman & Tyler, 1994). Cultural alienation refers to a sense of disconnect from established social norms and values of the host culture (Miller, Birman et al., 2009; Seeman, 1975). Elder immigrants may feel alienated as a result of strong attachment to heritage values and limited contact with the host culture (Fitzpatrick & Freed, 2000; Miller et al., 2006; van Selm et al. 1997). More specifically, former Soviet elders express a strong commitment to the heritage culture and report feeling unfulfilled in the U.S. (Fitzpatrick & Freed, 2000). They recognize America's economic advantages, but feel dissatisfied with social and family life (Ucko, 1986). They also perceive Americans as impersonal and insincere (Dunaev, 2012).

Acculturation and Life Domains

The family domain. Immigrants from the former Soviet Union highly value relationships with extended family members. The elderly rely on their family's support, so they typically emigrate in order to remain close to family members through old age (Iecovich et al., 2004; Ucko, 1986). In addition to providing care and support, younger family members give elders a purpose for the future in the new country. Older adults become invested in the success of children and grandchildren (Tsytsarev & Krichmar, 2000). They express hope that the new country will provide better education and employment opportunities and take pride in younger family members who actualize these hopes (Katz & Lowenstein, 1999).

The extended family serves both as elders' primary support system and aspiration for the future. Therefore, the successful adjustment of older immigrants highly depends on their family satisfaction. Elders who felt satisfied with family relationships and assistance experienced lower rates of depression (Kim-Goh, 2006). However, the acculturation process may also bring family conflict (Katz & Lowenstein, 1999). Family dynamics change under acculturative pressures. Younger immigrants acquire the host culture more rapidly than parents or grandparents (Ho & Birman, 2010), so older adults may come to depend on their children and grandchildren even for daily tasks (Vinokurov, 2001). Relying on younger relatives contrasts with elders' traditional roles as authority figures and may cause elders to feel dissatisfied with their new family positions. For this reason, greater acculturation to the host culture may enable older immigrants to feel independent, contributing to their family satisfaction (Treas & Mazumdar, 2002; Ucko, 1986). Heritage acculturation may also relate to greater family satisfaction because of stronger familial solidarity as a result of more frequent and involved intergenerational relationships (Lowenstein, 2002). The intensified relationships, however, may also create conflict, lowering family satisfaction (Katz, 2009). We thus explore the acculturation effects on elderly immigrants' family adjustment.

The social domain. Successful adaptation depends on forming supportive networks in the new country Jasinskaja-Lahti, Liebkind, Jaakkola, & Reuter, 2006; Lee, Crittenden, Yu, 1996). Researchers distinguish between the functions of social network composition and perceived support (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Cruza-Guet, Spokane, Caskie, Brown, Szapocznik, 2008). Studies suggest that immigrants need both host and heritage culture networks for successful social adjustment (Jasinskaja-Lahti et al., 2006). People from the heritage cultural background may be present in immigrants' networks early in the acculturation process. However, host networks may grow with acculturation to the host society (Jasinskaja-Lahti & Liebkind, 2007). Acculturation may also affect the perceived support from immigrants' networks, an important element of elders' social adjustment. Immigrants not acculturated to the host culture may need the security of counting on heritage networks for both instrumental and emotional support, while the perception of support from host communities may help bridge the cultural gap (Barnes & Aguilar, 2007). Therefore, network composition and perceived support both serve as measures of adjustment in the social domain.

Host and heritage acculturation may relate differently to the perceived composition and support of social networks. Because of cultural barriers, older immigrants have difficulty establishing connections with host networks (Treas & Mazumdar, 2002; Yoo & Zippay, 2012). Yet, heritage acculturation helps them form social relationships with other immigrants (Vinokurov & Trickett, under review). Therefore, Russian-speaking elders with low American acculturation may benefit from having more friends from the former Soviet Union. Additionally, acculturation may affect immigrants' perceived support from existing networks. Higher host culture acculturation related to greater support from both host and heritage networks in a study with adult immigrants (Jasinskaja-Lahti & Liebkind, 2007). Nevertheless, elderly Korean immigrants preferred to seek the support of people from their own ethnicity in one study (Yoo & Zippay, 2012). Elderly former Soviets may also be more likely to socialize with other Russian-speaking émigrés in their proximal community.

The medical care domain. Health is one of the major concerns for older Soviet immigrants (Kim-Goh, 2006). They may pay heightened attention to their health after immigration because they do not want to burden adult children with their care (Aroian, Khatutsky, Tran & Balsam, 2001). For the same reason, they may prefer to use formalized services rather than ask family members for help. Consequently, elders worry about availability of satisfactory medical assistance in light of declining health. Having spent the majority of their lives using a socialized medical system, they expect free, accessible services (Aroian & Vander Wal, 2007). Thus, unlike other immigrant groups, they tend to overuse, not underuse, the medical system because norms of the heritage culture encourage it (Aroian et al., 2001). Yet, most immigrant elderly in the U.S. face disparities in terms of access and quality of health care compared to non-immigrant older adults (Aroian et al., 2001; Lum & Vanderaa, 2010). To overcome these disparities, immigrant elders need to effectively navigate the U.S. medical system, which requires familiarity with English and American healthcare.

The Present Study: Questions and Hypotheses

This study examines the relationship of host and heritage acculturation to outcomes related to the psychological wellbeing, family life, social adjustment, and medical care of Russian-speaking older adults in the U.S. To assess the unique effects of acculturation, we control for time in the U.S. in addition to demographic characteristics known to influence immigrants' adjustment, including gender, marital status, education level, disability, functional health status, and living arrangements (Birman & Tyler, 1994; Jang et al., 2007).

With respect to overall psychological wellbeing, we expect a positive relation between American acculturation and psychological wellbeing: elders with higher host acculturation will feel less distress and alienation and experience greater overall satisfaction with life. We also predict Russian acculturation to relate to greater overall life satisfaction as well as feelings of cultural alienation. In addition, we explore how Russian acculturation affects psychological distress.

We use the outcome of family satisfaction to describe adjustment in the family domain. Because of the acculturation gap between older and younger generations, we expect greater host acculturation to relate to higher family satisfaction. Greater heritage acculturation may also contribute to family satisfaction, but no prior studies have assessed this relationship for elderly émigrés.

The social domain includes the outcomes of perceived network composition and social support. We expect Russian acculturation to relate to larger networks in the Russian-speaking community as well as greater support from these networks. We also hypothesize that American acculturation will relate to more perceived host connections and support.

Finally, in the medical domain, we will relate acculturation to elders' satisfaction with health care. American acculturation would expectedly relate to greater health care satisfaction. Heritage acculturation, on the other hand, may influence expectations for the care quality that differ from U.S. standards. Therefore, Russian acculturation will possibly relate to lower satisfaction with the American medical system and providers.

Method

Data and Sample

The data reported here were collected as part of a larger study with support from the Maryland Office of New Americans. The agency provided the researchers with a list of all families from the former Soviet Union who arrived to Maryland as refugees between 1989 and 1999. Russian-speaking interviewers contacted families by phone to identify eligible working-age adults, adolescents, and elders. Ninety-seven of the elderly participants were members of the contacted families and another 264 were recruited through a snowball sampling technique. The snowball method involved qualitative interviews with 12 key informants, who assisted in assembling groups of 6-40 former Soviet elders who completed a standardized survey in Russian (Vinokurov, 2001). In order to capture the experiences of those immigrating in late adulthood, we included women who were over 55 years old and men who were over 60 years old at the time they entered the U.S. The age cutoff corresponds to the age of retirement for men and women in the former Soviet Union. Those arriving at a younger age would have likely had a different acculturation experience, so they were excluded from the analyses (N = 44). Another 32 people were excluded after listwise deletion because of missing responses for key variables.

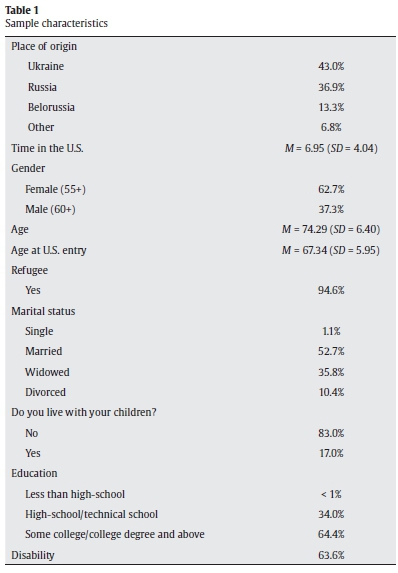

The final sample included 285 elder adults. Table 1 describes demographic characteristics of the participants. Over half were women (62%). The majority came from Ukraine (43%) or Russia (38%). Most of the participants were married (53%) or widowed (35%) and held a college degree or beyond (63%). Nearly all (94%) reported refugee status currently or in the past. The average age of the participants was 74, ranging from 59 to 94. Their average age of arrival was 67.3 and the highest was 86.6. On average participants had spent seven years in the U.S. (SD = 4.00). Only a minority (17.0%) resided with their extended families. Over half (63.6 %) reported having a serious illness that interfered with daily life.

The Community Context

The study participants resided in two large suburban metropolitan areas. Thirty five percent came from one of the metropolitan areas and the rest were spread across 8 contiguous communities outside another metropolitan area. Importantly, the material resources that elders could access were not dependent on the community context. The vast majority in both metropolitan areas had refugee status and received various assistance programs (92%) including public housing assistance (Vinokurov & Trickett, under review). Interestingly, receiving public assistance was not associated with stigma. On the contrary, elders often reported gratitude to the U.S. government for housing assistance, which often allowed them to live in subsidized apartment buildings with other Russian speakers, as well as health insurance and other aid, since their productive work lives had been in another country. Additionally, many elders lived close to public transportation and had access to Russian-speaking doctors and other health services (Vinokurov & Trickett, under review).

Although the larger community contexts between the two areas differed in ethnic density (see Birman, Trickett, & Buchanan, 2005), elders in both metropolitan areas could easily access social and cultural resources (Vinokurov & Trickett, under review). The proximal residential context rather that the larger neighborhood defined elders' community experiences. The majority resided in apartment buildings with large numbers of Russian-speaking elders living in close proximity. These residences provided opportunity to form formal and informal associations offering assistance and socialization (Vinokurov & Trickett, under review). Resources in the apartment buildings included community centers, large meeting rooms, resident councils, and social and cultural activities. Both Russian-speaking and some American neighbors helped and supported elderly immigrants with everyday issues and acculturative difficulties. The communities organized various informational, cultural and social events for elderly residents attended by many Russian-speaking elders. Even elders living away from ethnic clusters or with adult children kept in contact with the Russian-speaking community and often knew of and attended social and cultural activities (Vinokurov & Trickett, under review). Thus, even though the neighborhoods where elders resided provided different opportunities for Russian-speaking immigrants who worked or attended school, the proximal contexts in both communities facilitated social and cultural participation with the Russian speaking community and access to culture-specific resources.

Measures

All measures were translated into Russian. A collaborative translation process was rooted in the ecological theory in order to enhance cultural sensitivity and produce linguistically and culturally valid research instruments (Vinokurov, Geller, & Martin, 2007). Immigrants with professional translation experience developed the initial Russian version of the survey. Then, other Russian-speaking immigrants checked the translation and discussed any issues with the researchers. The revised translated measures were cognitively pretested with four Russian-speaking immigrants.

Acculturation to American and Russian cultures. Two parallel scales assessed acculturation to American and to Russian cultures along the dimensions of language, identity, and behavior (Birman & Trickett, 2001). Because all participants were native Russian speakers who arrived to the U.S. in late adulthood, the Russian scale measuring language ability was not administered. The English scale consisted of nine items (α = .96) measuring command of English on a four-point Likert scale that rated speaking and understanding in different situations (e.g., on the phone). The American and Russian identity subscales included four parallel items regarding identification with American (α = .88) and Russian (α = .92) cultures. On a 4-point scale, respondents indicated how much they felt they belonged to and had a positive regard of the American and Russian cultures. The eleven behavior items asked the extent to which participants engaged in the American (α = .79) and Russian (α = .75) cultures through activities, such as speaking, reading, and eating. In this study, we averaged the subscales to estimate an overall measure of American (α = .92) and Russian (α = .82) acculturation.

Life satisfaction. The perceived Quality of Life scale (Fazel & Young, 1988) contains 17 items about satisfaction with different aspect of life, including family, leisure time, health, and living standard. The scale was slightly modified to exclude employment-related items likely to be inapplicable for the age group of the sample. The administered scale contained 14 items (α = .84). Participants indicated how they felt about aspects of their life on a five-point scale ranging from 1(very badly) to 5 (very well).

Hopkins symptoms checklist. The Hopkins symptoms checklist (Green, Walkey, McCormick, & Taylor, 1988) measures levels of psychological distress through 21 items describing symptoms of depression, somatization, and performance anxiety. The responses range from 1 (not at all distressing) to 4 (extremely distressing). The internal consistency of the scale in the study was .91.

Cultural alienation. The alienation scale measures immigrants' feelings of social and cultural estrangement (Nicassio, 1993). Birman & Tyler (1994) translated the scale to Russian and excluded the I don't know response. The 10-item scale (α = .66) includes statements, such as "It is difficult for me to understand the American way of life" and "I feel like I belong in American society" (reverse-coded). Items were rated on a four-point scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree).

Family satisfaction. The researchers adapted Carver and Jones' (1992) 20-item family satisfaction scale for adults designed to measure feelings of satisfaction with extended family members and relationships (e.g., "I would do anything for a member of my family"). They omitted four of the items as inapplicable for older adults because of reference to parental rules and rephrased the remaining items in present tense. The scale ranged from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) and included six reverse-scored items. Carver and Jones reported an internal consistency of .98 and two-month test-retest reliability of .88. The calculated reliability for the present sample was .78.

Perceived social support. The perceived social support measure was adapted from Seidman et al.'s (1995) adolescent perceived microsystem scale and has been used in previous studies with adolescent and working adult samples (Birman & Trickett, 2001; Birman et al., 2002). The reference groups on the scale were altered to reflect the social connections of elder adults. Participants rated how much they could count on American and Russian friends for help with private matters, public programs, and money on a 3-point scale from 1 = not at all to 3 = a great deal. They also rated how much they enjoyed the overall interactions with American and Russian friends. We averaged the support rating across all four areas to calculate overall scores for perceived support from American friends and perceived support from Russian friends.

Social networks composition. The social networks measure assesses the perceived size and type of participants' social networks (Birman & Trickett, 2001). Participants indicated the number of Russians, Russian Jews, Americans, American Jews, and others, with whom they socialized, had dinner, or were close friends. We added the number of American and Russian friends to calculate the size of elders' network in the host and heritage communities.

Satisfaction with medical care. The present study used eight items (α = .80) from the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (Marshall, Hays, Sherbourne, & Wells, 1993) assessing the dimensions of general satisfaction, interpersonal aspects, and time spent with doctors. Participants rated their satisfaction from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). The modified scale specified that items referred to American doctors only.

Disability and health status. Disability was measured by a single yes or no question about whether or not participants had a serious illness that interfered with their daily lives. A health status scale included 5 questions about the extent to which health problems interfered with daily life in the past month (1= not at all, 5 = very much). The scale was created for this study and the measured reliability was .89.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

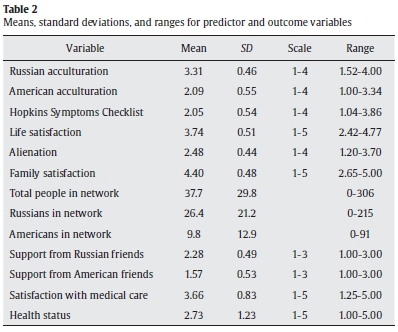

Table 2 displays the means, ranges, and standard deviations of participants' average acculturation scores and domain outcomes. As expected, participants were relatively highly oriented towards their own ethnic (Russian) culture, M = 3.31, SD = 0.46, and much less so toward American culture, M = 2.09, SD = 0.55 (on a 4-point scale). They reported high average scores of family satisfaction (M = 4.40, SD = 0.48) and life satisfaction (M = 3.74, SD = 0.51), both on a 5-point scale. Additionally, on average, participants reported almost 3 times as many Russians (M = 26.4, SD = 21.23) as Americans (M = 9.8, SD = 12.88) in their overall network (M = 37.7, SD = 29.78) and much higher satisfaction with their Russian (M = 2.28, SD = 0.49) than American friends (M= 1.57, SD = 0.53).

Table 3 displays bivariate correlations between acculturation and outcome variables, time spent in the U.S, gender (male), and education levels (college and beyond). The overall Russian and American acculturation scores showed a weak inverse correlation (r = -.17, p < .01). Time spent in the U.S. related significantly to higher American acculturation (r = .29, p < .01) and marginally to lower Russian acculturation (r = -.11, p = .06), suggesting that over time elders acquire some American culture, while their heritage cultural orientation remains high.

Although significant, inter-correlations show that psychological adaptation and the domain-specific outcomes are relatively independent. While all of the psychological adaptation measures were significantly related to each other, the magnitude of the correlations was modest, with strongest association between the Hopkins Symptom checklist and life satisfaction scores (r = -.46, p < .01). Within each of the life domains, the measures were likewise significantly but not highly correlated. For example, the significant correlation between support and satisfaction scores in the family domain was .34. Additionally, support received from Russian friends positively related to support from American friends (r = .28, p < .01). The support items also correlated with the participants' network composition (r = .54, p < .01 for American network and support and r = .16, p < .01 for Russian network and support). Correlations show that outcomes within each domain are associated, but they are fairly discrete constructs. Further, the life domain measures of adaptation were not highly related to the psychological measures. Thus, they were examined independently in the regression analyses.

Hypothesis Testing

To test study hypotheses, participants' overall Russian and American acculturation scores, together with the control variables of time in the U.S., demographic characteristics, and disability and health status, were regressed onto the outcome variables in each domain. Table 4 presents the unstandardized regression coefficients.

Psychological adaptation. With respect to psychological outcomes, it was hypothesized that American acculturation would uniquely contribute to lower distress level, lower alienation, and greater life satisfaction. Russian acculturation was expected to contribute to greater alienation and greater life satisfaction. As expected, American acculturation uniquely contributed to lower psychological distress, β = -.19, p < .01, lower feelings of alienation, β = -.38, p < .001 and greater satisfaction with life, β = .29, p < .001. Russian acculturation predicted greater alienation, β = .12, p < .05, but also higher life satisfaction, β = .11, p < .05, concurring with the hypotheses. It did not significantly affect psychological distress levels. Physical illness, however, related to higher distress, β = .26, p < .001, and lower life satisfaction, β = -.46, p < .001.

To further explore the positive relationship between both Russian and American acculturation and life satisfaction, we conducted 14 regression analyses of the items that comprise the life satisfaction scale. The 14 items covered satisfaction with life overall, material wealth and standard of living, amount and quality of leisure time, health, neighborhood, and family life (Fazel & Young, 1988). Each regression included the two acculturation predictors, controlling for demographics, health and disability, and living arrangements. Table 5 summarizes the regressions' results. American acculturation uniquely contributed to ten of the 14 items relating to satisfaction with life overall, the family, standard of living, amount of free time, and neighborhood. American acculturation approached significance for three additional items about family and leisure time and quality of goods and services. Russian acculturation significantly related to two of the 14 items that addressed how satisfied participants were with how they spend their free time with the family and in general. Russian acculturation also marginally related to three items regarding elders' overall life satisfaction, the pleasure they get from life, and satisfaction with their neighbors.

The family domain. In the family domain, American acculturation was expected to uniquely contribute to family satisfaction after controlling for demographics, health and disability, and time spent in the U.S. As expected, American acculturation related to greater family satisfaction, β = .18, p < .05. Russian acculturation also marginally contributed to family satisfaction, β = .12, p = .06. Married participants experienced greater family satisfaction than participants who were single β = -.56, p < .05 or divorced, β = -.37, p < .001. Those who lived with their children also reported greater family satisfaction than those who did not, β = -.25, p < .01.

The social domain. In the social domain, American acculturation was expected to relate to more American friends and greater perceived support from Americans. Likewise, Russian acculturation was predicted to contribute to more Russian friends and support. Regressions testing the hypotheses regarding the number of friends included the control variable of total network size. The ones testing hypotheses regarding satisfaction with support included controls for the size of Russian and American networks respectively. As expected, greater American acculturation uniquely contributed to more

Americans in elders' networks, β = .76, p < .001, and greater perceived support from Americans, β = .24, p < .001. Similarly, Russian acculturation related to more Russian friends, β = .14, p < .001, and perceived support from them, β = .13, p < .05. Unexpectedly, greater American acculturation related to fewer Russian friends, and greater Russian acculturation to fewer American friends, suggesting that, as older immigrants adopt the host culture, they expand host networks that replace the heritage ones; whereas maintaining the heritage culture precludes formation of friendships with Americans.

The medical care domain. In the medical domain, American acculturation was expected to relate to greater satisfaction with care. Russian acculturation, on the other hand, was hypothesized to relate to lower satisfaction with medical care. None of the hypotheses were supported and no single predictor significantly related to satisfaction with medical care.

Discussion

This study examined how acculturation related to the adjustment of Russian-speaking immigrants resettled in late adulthood. We approached this topic by assessing acculturation to both the host and heritage culture from a life domains perspective well suited for elderly populations, for whom remaining near family was a primary immigration motive. Although previous studies with older immigrants from several ethnic backgrounds have focused on the direct, psychological effects of acculturation, in this study we aimed to show that adaptation refers to positive outcomes in various domains of life in addition to psychological wellbeing (Chiriboga, 2004; Ritsner et al., 2000; Tran et al., 2008; Wrobel et al., 2009). Both host and heritage acculturation can serve as resources or impediments to positive adjustment. Results supported the life domains approach and highlighted the value of this framework for older immigrant populations.

The acculturation patterns of the present sample resembled those found in previous studies. Elder immigrants from different ethnicities remain highly acculturated to their heritage culture over time and acquire the host culture to lesser extents (Abu-Baden et al., 2011; Jang et al., 2007; Miller, Wang et al., 2009). Staying longer in the country of resettlement does not have a strong association with levels of acculturation to either culture. Rather, for older adult immigrants, host and heritage acculturation seem to occur relatively independently of each other and of time spent in the host country, as suggested by the weak correlations of these constructs. Therefore, we examined the independent effects of these acculturative processes on adjustment and recommend this approach for future research (Birman et al., 2014).

Host Acculturation Effects

Higher American acculturation facilitated elders' psychological adjustment and functioning in the family and social domains. Consistent with previous findings and the present hypotheses, participants with high host acculturation reported greater psychological wellbeing on all three measures used, suggesting that familiarity with the local language and cultural norms reduces adjustment difficulties. Greater American acculturation also contributed to family satisfaction, possibly because of a reduced intergenerational acculturative gap (Katz & Lowenstein, 1999; Treas & Mazumdar, 2002). Acculturative struggles claim much of younger immigrants' attention (Treas & Mazumdar, 2002). Therefore, younger relatives may provide elders with stability, but not with satisfactory social or emotional support. More acculturated elders can have a degree of independence and understanding of the problems their family members face in the U.S., leading to improved satisfaction with filial relationships. It is also likely that elders who are more acculturated to the American culture can participate in cultural activities together with their extended family, leading to higher family satisfaction.

The results also confirmed advantages of American acculturation for forming larger and more supportive social networks within the host community. Although not surprising, this finding shows that some people who resettle late in life may cultivate relationships in the host society despite difficulties of language, cultural barriers, and severed life-long social ties. However, overall American networks were not extensive and seemed to provide relatively little support. Even though 15 percent of the participants reported 10 or more Americans in their networks, a third had no American friends or acquaintances. The perceived support from Americans was also relatively low.

Findings also show an association between American acculturation and fewer Russian friends. With acculturation to the host country, elderly immigrants may possibly lose ties to co-ethnic communities and even become alienated from them. Unfortunately, prior studies have not considered the separate roles of host and co-ethnic support throughout the acculturation process of elderly immigrants. Future research should explore the potential negative impact of host acculturation on support from co-ethnic networks that we found in this study.

While overall, higher American acculturation was related to a number of indices of positive adjustment, it is important to note that the overall level of American acculturation was low, (2.09 on a 4 point scale; the highest score in the sample was 3.34), particularly relative to Russian acculturation. Thus, it is important to note that the effects observed here were associated with modest increase in host acculturation levels rather than the more co-equal idea suggested by the "bicultural" construct.

Heritage Acculturation Effects

Heritage acculturation presented advantages in the co-ethnic social adjustment domain. Those with higher Russian acculturation reported larger social networks and greater support within their own ethnic communities. Heritage networks may provide the only social contacts outside of the elders' family members (Jasinskaja-Lahti & Liebskind, 2006; Litwin, 1997). This held true for the majority of the participants in this sample. Eighty five percent reported having more than 10 Russian-speaking friends or acquaintances in their overall network.

In regard to psychological adjustment, heritage acculturation effects were mixed. Elders with higher Russian acculturation reported greater overall life satisfaction. As a result, both American and Russian acculturation related to greater overall life satisfaction, as suggested by biculturalism models. Yet, heritage acculturation may also present challenges to elders' adaptation. Participants with higher Russian acculturation reported increased feelings of alienation from the American society. Thus, integrating the different social and cultural values of the former Soviet Union and the U.S. may create struggles for these elders (Fitzpatrick & Freed, 2000).

Russian acculturation was also related to having fewer American friends, suggesting that maintaining the heritage culture precludes the formation of friendships with Americans. This finding, combined with the finding that American acculturation was related to having fewer Russian friends, suggests a subtractive process where becoming more American is associated with an expanding host network that displaces Russian social circles. This pattern of findings further suggests that elders may become more involved in one culture at the expense of the other. This finding challenges the notion that biculturalism, or a balanced integration into both social worlds, is possible for elderly immigrants.

Contrary to the hypotheses, acculturation to either culture did not relate to satisfaction with the medical care domain. Possibly, the medical care resources that elders used differed from those measured in this study. The medical care measure included several items that rated satisfaction with American doctors. However, the local community provided access to Russian-speaking doctors that elders might have been more likely to visit. In a previous study with former Soviet elders resettled in another U.S. metropolitan area, participants exclusively visited doctors who spoke Russian (Aroian et al., 2001). Therefore, it is possible that the measure of medical satisfaction in this study did not capture the care that elders received.

Acculturation and Life Satisfaction

In the initial analyses, host and heritage both related to greater overall satisfaction with life. To follow up on this finding, we explored how host and heritage acculturation related to the life domains represented in the items that create the life satisfaction scale (Fazel & Young, 1988). Host acculturation related to items regarding satisfaction with material needs, such as income, standard of life, neighborhood, and dwelling. By contrast, heritage acculturation related to items regarding leisure time, including free time in general and with family. These additional analyses provide further support for the life domains approach. Both host and heritage acculturation contributed to positive adjustment, but through different processes. Consequently, we propose that no single acculturative course can ensure wellbeing across all spheres of life. Rather, the study results suggest that the diverse ways to acculturate entail cultural skills more suitable for some life domains than for others.

Summary and Conclusion

This study adopted a life-domains approach to examine the direct effects of acculturation on adjustment. Findings suggest that both host and heritage acculturation have different significance in elders' resettlement experience. Host acculturation appears beneficial across several domains, which may result from the daily needs that the majority culture imposes on resettling individuals. Nevertheless, the culture of origin remains deeply engrained in adults who immigrate late in life, which appears to have mixed effects on adapting. The theoretical framework that guided this study helped detect these previously overlooked intricacies of the Russian-speaking elders' resettlement experiences.

The study showed that acculturation to the American and Russian culture had advantages for the elders in some circumstances and disadvantages in others. Russian acculturation proved beneficial for Russian networks and social support, but also reduced the size of American networks, as well as heightened feelings of alienation. Conversely, while American acculturation was associated with a number of adaptive benefits, it was also related to reduced size of Russian networks, an important source of social support for the elders. Living with such cultural conflicts may be normal throughout acculturation process. Thus, at the societal level, it is liberating to have policies and attitudes that legitimize and respect diverse ways of acculturating, rather than privileging a particular acculturative style over others.

In this way, this study suggests that efforts to pressure immigrants to adopt a particular acculturative style, whether it is assimilation or biculturalism, are misguided, and, at least with elderly immigrants, potentially unrealistic. Compared to working-age adults or children, elder immigrants are less likely to seek a new life. Although functioning in the new culture necessitates host language and cultural skill, heritage acculturation also helps elderly immigrants form positive social relationships with the Russian-speaking immigrant community. Therefore, Russian-speaking elders benefit from preserving their heritage culture without necessarily having the option to become bicultural. Future research may address the issue of whether such relationships represent a choice to remain close to co-ethnic relationships and/or a lack of acceptance from the receiving community. However, the data here suggest that biculturalism may or may not be advantageous depending on the life domain and generational status. Groups and individuals may pursue a range of different ways of acculturating and adapting to their particular immigration circumstances.

Limitations and Future Direction

Findings are based on cross-sectional and correlational data analysis and it is possible that results reflect behavioral patterns of psychological, social, and family wellbeing rather than effects of acculturation. For example, participants most satisfied with their lives may be the ones who acculturate to the American culture while successfully maintaining their heritage culture. Also, more Americans in elders' networks may contribute to greater American acculturation, and more Russian friends may reinforce Russian acculturation. Future studies should address this limitation through longitudinal designs that can infer causal direction. Additionally, the present conclusions may not extend to other Russian-speaking elderly immigrants residing in different areas and communities, although the demographic characteristics of the sample are similar to other Russian-speaking refugees in the U.S.

Importantly, further research can continue to explore the diverse patterns of acculturation, and varieties of adaptation of immigrants across diverse age groups in different community and national contexts. Although this study took an ecological approach to immigrants' wellbeing, variables at the communal and societal levels were not directly examined. Rather, the current study considered the community context only as it shaped the daily transactions between individuals and their setting in different life domains. Future work can examine the acculturative process as it evolves in across-age groups in different national and community contexts.

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.

References

Abu-Bader, S. H., Tirmazi, M. T., & Ross-Sheriff, F. (2011). The impact of acculturation on depression among older Muslim immigrants in the United States. Journal of Gerontological social work, 54, 425-48. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2011.560928 [ Links ]

Arends-Tóth, J., & van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2004). Domains and dimensions in acculturation: Implicit theories of Turkish-Dutch. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 28(1), 19-35. [ Links ]

Aroian, K. J., Khatutsky, G., Tran, T. V., & Balsam, A. L. (2001). Health policy and systems health and social service utilization former Soviet Union. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 33, 265-271. [ Links ]

Aroian, K. J., & Vander Wal, J. S. (2007). Health service use in Russian immigrant and nonimmigrant older persons. Family & community health, 30, 213-23. [ Links ]

Barnes, D. M., & Aguilar, R. (2007). Community social support for Cuban refugees in Texas. Qualitative Health Research, 17, 225-37. doi: 10.1177/1049732306297756 [ Links ]

Berry, J. W. (1980). Acculturation as varieties of adaptation. In Padilla, A. M. (Ed.), Acculturation, theory, models, and some new findings (pp. 9-25). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. [ Links ]

Birman, D. (1994). Acculturation and human diversity in a multicultural society. In E. J. Trickett, R. Watts, & D. Birman (Eds.), Human diversity: Perspectives on people in context (pp. 261-284). San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. [ Links ]

Birman, D. (1998). Biculturalism and perceived competence of Latino immigrant adolescents. American journal of community psychology, 26, 335-354. [ Links ]

Birman, D., Persky, I., & Chan, W. Y. (2010). Multiple identities of Jewish immigrant adolescents from the former Soviet Union: An exploration of salience and impact of ethnic identity. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 34, 193-205. doi: 10.1177/0165025409350948 [ Links ]

Birman, D., & Simon, C. D. (2013). Acculturation research: Challenges, complexities, and possibilities. In F. Leong, L. Comas-Diaz, G. Nagayama Hall, & J. Trimble (Eds.), APA Handbook of Multicultural Psychology. Washington, DC.: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Birman, D., Simon, C. D., Chan, W. Y., & Tran, N. (2014). A life domains perspective on acculturation and psychological adjustment: A study of refugees from the former Soviet Union. American Journal of Community Psychology. 53, 60-72. doi: 10.1007/ s10464-013-9614-2 [ Links ]

Birman, D., & Trickett, E. J. (2001). Cultural transitions in first-generation immigrants: Acculturation of Soviet Jewish Refugee adolescents and parents. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32, 456-477. [ Links ]

Birman, D., Trickett, E. J., & Buchanan, R. M. (2005). A tale of two cities: Replication of a study on the acculturation and adaptation of immigrant adolescents from the former Soviet Union in a different community context. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35, 83-101. [ Links ]

Birman, D., Trickett, E. J., & Vinokurov, A. (2002). Acculturation and adaptation of Soviet Jewish refugee adolescents: predictors of adjustment across life domains. American journal of community psychology, 30, 585-607. [ Links ]

Birman, D., & Tyler, F. B. (1994). Acculturation and alienation of Soviet Jewish refugees in the United States. Generic Social and Psychological Monographs, 120, 101-115. [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1988). Interacting systems in human development. Research paradigms: Present and future. In N. Bolger, A. Caspi, G. Downey, & M. Moorehouse (Eds.), Persons in context: Developmental processes (pp. 25-49). New York, NY: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. [ Links ]

Carver, M. D., & Jones, W. H. (1992). The Family satisfaction scale. Social Behavior and Personality, 20, 71-84. [ Links ]

Chiriboga, D. A. (2004). Some thoughts on the measurement of acculturation among Mexican American elders. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 26, 274-292. doi: 10.1177/0739986304267205 [ Links ]

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310-357 [ Links ]

Cruza-Guet, M. -C., Spokane, A. R., Caskie, G. I. L., Brown, S. C., & Szapocznik, J. (2008). The relationship between social support and psychological distress among Hispanic elders in Miami, Florida. Journal of counseling psychology, 55, 427-41. doi: 10.1037/ a0013501 [ Links ]

Dunaev, E. (2012). Acculturation, psychological distress, and family adjustment among Russian immigrants in the United States (Doctoral Dissertation). Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine. Department of Psychology. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. [ Links ]

Escobar, J., & Vega, W. A. (2000). Mental health and immigration's AAAs: Where are we and where do we go from here? Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 188, 736-740. [ Links ]

Fazel, M. K., & Young, D. M. (1988). Life quality of Tibetans and Hindus: A function of religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 27, 229-242. [ Links ]

Fitzpatrick, T. R., & Freed, A. O. (2000). Older Russian immigrants to the USA: Their utilization of health services. International Social Work, 43, 305-323. [ Links ]

García-Ramírez, M., De la Mata, M., Paloma, V. & Hernández-Plaza, S. (2011). A liberation psychology approach to acculturative integration of migrant populations. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47, 86-97 [ Links ]

Green, D. E., Walkey, F. H., McCormick, I. A., & Taylor, A. J. W. (1988). Development and evaluation of a 21-item version of the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist with New Zealand and United States respondents. Australian Journal of Psychology, 40, 61-70. [ Links ]

Hernández-Plaza, S., García-Ramírez, M., Camacho, C., & Paloma, V. (2010). New settlement and well-being in oppressive contexts: A liberation psychology approach. In S. Carr (Ed.), The Psychology of Global Mobility. Series: International and Cultural Psychology (pp. 235-256). New York: Springer [ Links ]

Ho, J. & Birman, D. (2010). Acculturation gap in Vietnamese refugee families: Impact on family adjustment. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 34, 22-33. [ Links ]

Iecovich, E., Barasch, M., Mirsky, J., Kaufman, R., Avgar, A., & Kol-Fogelson, A. (2004). Social support networks and loneliness among elderly Jews in Russia and Ukraine. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 306-317. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2004.00022.x [ Links ]

Jang, Y., Kim, G., Chiriboga, D., & Kallimanis, B. (2007). A bidimensional model of acculturation for Korean American older adults. Journal of Aging Studies, 21, 267-275. [ Links ]

Jasinskaja-Lahti, I., Liebkind, K., Jaakkola, M., & Reuter, A. (2006). Perceived discrimination, social support networks, and psychological well-being among three immigrant groups. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37, 293-311. doi: 10.1177/0022022106286925 [ Links ]

Jasinskaja-Lahti, I., & Liebkind, K. (2007). A structural model of acculturation and well-being among immigrants from the former USSR in Finland. European Psychologist, 12, 80-92. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.12.2.80 [ Links ]

Katz, R. (2009). Intergenerational family relations and life satisfaction among three elderly population groups in transition in the Israeli multi-cultural society. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 24, 77-91. doi: 10.1007/s10823-009-9092-z [ Links ]

Katz, R., & Lowenstein, A. (1999). Adjustment of older Soviet immigrant parents and their adult children residing in shared households: An intergenerational comparison. Family Relations, 48, 43-50. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/585681 [ Links ]

Kim-Goh, M. (2006). Correlates of depression among the Soviet Jewish immigrant elderly. Journal of human behavior in the social environment, 13(2), 35-47. [ Links ]

Klinger, S. (2007). Russian-Jewish Americans and American Jewry: Encounter, identity, and integration. Sociological Papers, 12, 24-34. [ Links ]

Krause, N., & Goldenhar, L. (1992). Acculturation and psychological distress in three groups of elderly Hispanics. Journal of Gerontology, 47, S279-S288. [ Links ]

Lee, M. S., Crittenden, K. S., & Yu, E. (1996). Social support and depression among elderly Korean immigrants in the United States. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 42, 313-327. [ Links ]

Liebkind, K., & Jasinskaja-Lahti, I. (2000). Acculturation and psychological well-being among immigrant adolescents in Finland: A comparative study of adolescents from different cultural backgrounds. Journal of Adolescent Research, 15, 446469. [ Links ]

Litwin, H. (1997). The network shifts of elderly immigrants: the case of Soviet Jews in Israel. Journal of cross-cultural gerontology, 12, 45-60. [ Links ]

Lowenstein, A. (2002). Solidarity and conflicts in coresidence of three-generational immigrant families from the former Soviet Union. Journal of Aging Studies, 16, 221-241. doi:10.1016/S0890-4065(02)00047-6 [ Links ]

Lum, T., & Vanderaa, J. (2010). Health disparities among immigrant and non-immigrant elders: The association of acculturation and education. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 12, 743-753. [ Links ]

Marshall, G. N., Hays, R. D., Sherboune, C. D., & Wells, K. B. (1993). The structure of patient satisfaction with outpatient medical care. Psychological Assessment, 5, 477-483. [ Links ]

Miller, A. M., Birman, D., Zenk, S., Wang, E., Sorokin, O., & Connor, J. (2009). Neighborhood immigrant composition, acculturation, and cultural alienation in former Soviet immigrant women. Journal of Community Psychology, 37, 88-105. [ Links ]

Miller, A. M., Sorokin, O., Wang, E., Feetham, S., Choi, M., Wilbur, J. (2006). Acculturation, social alienation, and depressed mood in midlife women from the former Soviet Union. Research in Nursing & Health, 29, 134-46. [ Links ]

Miller, A. M., Wang, E., Szalacha, L. A., & Sorokin, O. (2009). Longitudinal Changes in Acculturation for Immigrant Women from the former Soviet Union. Journal of cross-cultural psychology, 40, 400-415. doi: 10.1177/0022022108330987 [ Links ]

Nicassio, P. M. (1983). Psychosocial correlates of alienation: Study of a sample of Indo-Chinese refugees. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 14, 337-351. [ Links ]

Nguyen, H., Messé, L., & Stollak, G. (1999). Toward a more complex understanding of acculturation and adjustment cultural involvements and psychosocial functioning in Vietnamese youth. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30, 5-31. [ Links ]

Persky, I., & Birman, D. (2005). Ethnic identity in acculturation research: A study of multiple identities of Jewish refugees from the former Soviet Union. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36, 557-572. doi:10.1177/0022022105278542 [ Links ]

Polyakova, S. A, & Pacquiao, D. (2006). Psychological and mental illness among elder immigrants from the former Soviet Union. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 17, 40-49. [ Links ]

Portes, A., & Zhou, M. (1993). The new second generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 530(1), 74-96. [ Links ]

Prilleltensky, I. (2008). Migrant wellbeing is a multilevel, dynamic, value dependent phenomenon. American Journal of Community Psychology, 42, 359-364. doi: 10.1007/ s10464-008-9196-6 [ Links ]

Prilleltensky, I. (2012). Wellness as fairness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 49, 1-21. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9448-8 [ Links ]

Ritsner, M., Modai, I., & Ponizovsky, A. (2000). The stress support patterns and psychological distress of immigrants. Stress Medicine, 147, 139-147. [ Links ]

Ron, P. (2001). The process of acculturation in Israel among elderly immigrants from the former Soviet Union. Illness, Crisis, & Loss, 9, 357-368. [ Links ]

Rudmin, F. W. (2003). Critical history of the acculturation psychology of assimilation, separation, integration, and marginalization. Review of General Psychology, 7, 3-37. [ Links ]

Rudmin, F. W., & Ahmadzadeh, V. (2001). Psychometric critique of acculturation psychology: the case of Iranian migrants in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 42, 41-56. [ Links ]

Seeman, M. (1975). Alienation studies. Annual Review of Sociology, 1, 93-123. [ Links ]

Seidman, E., Allen, L., Aber, J. L., Mitchell, C., Feinman, J., Yoshikawa, H., ... Roper, G. C. (1995). Development and validation of adolescent-perceived microsystem scales: Social support, daily hassles, and involvement. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23, 355-388. [ Links ]

Shemirani, F. S., & O'Connor, D. L. (2006). Aging in a foreign country : Voices of Iranian women aging in Canada. Journal of Women & Aging, 18, 37-41. doi: 10.1300/ J074v18n02 [ Links ]

Swindle, R. W., Jr., & Moos, R. H. (1992). Life domains in stressors, coping, and adjustment. In W. B. Walsh, K. H. Craik, & R. H. Prices (Eds.), Person-environment psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Earlbaum. [ Links ]

Tran, T. V., Sung, T., & Huynh-Hohnbaum, A. L. T. (2008). A measure of English acculturation stress and its relationship with psychological and physical health status in a sample of elderly Russian immigrants. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 50, 37-50. [ Links ]

Treas, J., & Mazumdar, S. (2002). Older people in America's immigrant families: Dilemmas of dependence, integration, and isolation. Journal of Aging Studies, 16, 243-258. [ Links ]

Trickett, E. J. (2009). Community psychology: individuals and interventions in community context. Annual review of psychology, 60, 395-419. doi: 10.1146/annurev. psych.60.110707.163517 [ Links ]

Trickett, E. J. & Formoso, D. (2008). The acculturative environment of schools and the school counselor: Goals and roles that create a supportive context for immigrant adolescents. In H. Coleman & C. Yeh (Eds.), Handbook of School Counseling. New York, NY/Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Tsytsarev, S., & Krichmar, L. (2000). Relationship of perceived culture shock, length of stay in the U.S., depression, and self-esteem in elderly Russian-speaking immigrants. Journal of Social Distress and Homelessness, 9, 35-59. [ Links ]

Ucko, L. (1986). Perceptions of aging East and West: Soviet refugees see two worlds. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 1, 411-428. [ Links ]

Van Selm, K., Sam, D. L., & van Oudenhoven, J. P. (1997). Life satisfaction and competence of Bosnian refugees in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 38, 143-149. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00020 [ Links ]

Vinokurov, A. (2001). Development of the acculturative hassles inventory for Russian-speaking elderly immigrants (Doctoral Dissertation). University of Maryland, Baltimore County. [ Links ]

Vinokurov, A., Geller, D., & Martin, T. L. (2007). Translation as an ecological tool for instrument development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 6(2), article 3. [ Links ]

Vinokurov, A., & Trickett, E. J. (under review). Ethnic Clusters in Public Housing and Independent Living of Elderly Immigrants from the former Soviet Union. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. [ Links ]

Vinokurov, A., Trickett, E. J., & Birman, D. (2002). Acculturative hassles and immigrant adolescents: a life-domain assessment for Soviet Jewish refugees. The Journal of social psychology, 142, 425-45. doi: 10.1080/00224540209603910 [ Links ]

Wrobel, N. H., Farrag, M. F., & Hymes, R. W. (2009). Acculturative stress and depression in an elderly Arabic sample. Journal of cross-cultural gerontology, 24, 273-90. doi: 10.1007/s10823-009-9096-8 [ Links ]

Yoo, J. A., & Zippay, A. (2012). Social networks among lower income Korean elderly immigrants in the U.S. Journal of Aging Studies, 26, 368-376. doi: 10.1016/j. jaging.2012.03.005 [ Links ]

Yoon, E., Chang, C.-T., Kim, S., Clawson, A., Cleary, S. E., Hansen, M., ... Gomes, A. M. (2013). A meta-analysis of acculturation/enculturation and mental health. Journal of counseling psychology, 60(1), 15-30. doi: 10.1037/a0030652 [ Links ]

Zamanian, K., Thackrey, M., Brown, L. G., Lassman, D. K., & Blanchard, A. (1992). Acculturation and depression in Mexican-American elderly. Clinical Gerontologist 11, 109-121. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1300/J018v11n03_08 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

e-mail: agenko2@uic.edu

Manuscript received: 15/02/2014

Accepted: 24/04/2014