Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Enfermería Global

versão On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.20 no.63 Murcia Jul. 2021 Epub 02-Ago-2021

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.456511

Reviews

Bibliographic review on the historical memory of previous pandemics in nursing reviews on COVID-19: a secularly documented reality

1aEnfermera Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca de Murcia. Murcia. España.

1bGrupo Cuidados Enfermeros Avanzados del Instituto Murciano de Investigación Biosanitaria Arrixaca. Murcia. España.

2a Enfermera vinculada Hospital General Universitario Reina Sofía de Murcia. Murcia. España.

2bProfesora Contratada Doctora vinculada Universidad de Murcia. Murcia. España.

2cGrupo Cuidados Enfermeros Avanzados del Instituto Murciano de Investigación Biosanitaria Arrixaca. Murcia. España.

Objective:

We plan to map the content of recent reviews in the nursing area on COVID-19 to see if it refers to health crises due to epidemics and infectious diseases.

Methodology:

Descriptive narrative review. The Science Web, PubMed and Lilacs were consulted to identify the reviews; The content of the documents was consulted to detect the presence of descriptors and terms related to pandemics prior to the 21st century of humanity, taking into account the inclusion criteria and objectives of the study.

Conclusions

There may be reluctance to use documentation published more than a century ago; However, it would be advisable not to lose the historical memory of pandemic crises that humanity has suffered for millennia

Key words: Pandemics; Epidemics; History; Ancient History

INTRODUCTION

Since Coronavirus disease, responsible for COVID-19, emerged at the end of 2019, and subsequently since the declaration of the disease as a pandemic in March 2020, there has never been before such an increase in publications in journals indexed in the main bibliographic databases in just 12 months. These Bibliographic Databases have been open access for researchers and health care professionals. However, when we write about health crises, we should reasonably document the arguments bearing in mind the historical bibliography that support that epidemics and pandemics have existed for centuries. Documents written in all types of support on plague, typhus (gaol fever), whooping cough, measles, cholera, influenza, AIDS (HIV), meningitis, tuberculosis, could remind us that the situation created by the COVID-19 is not new. Infectious diseases in the form of epidemics or pandemics have accompanied the human race throughout history.

The correct use of terminology is also important. To consult the meaning of, among other concepts, epidemiology, plague, epidemic, pandemic, endemic, epidemiological outbreak, zoonosis, lazaretto, the dictionary of medical terms of the Royal Academy of Medicine of Spain1) can be consulted.

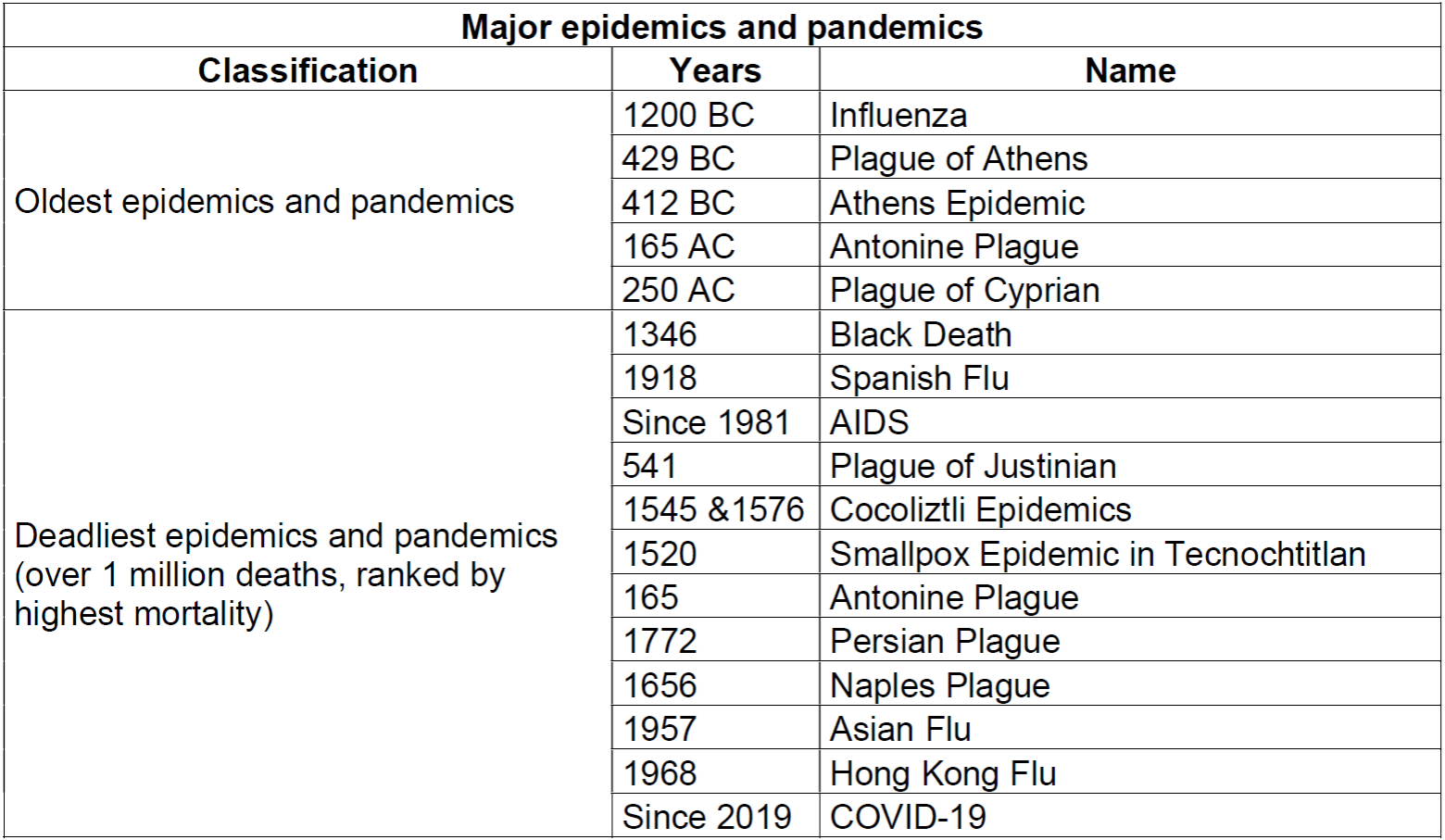

Detecting the oldest pandemics of human kind and those that have caused the greatest number of deaths could be the first step. The following Table, self-elaborated and based on a wide variety of literature and sources, lists the oldest and deadliest epidemics and pandemics.

Epidemics in Art

As a mere matter of extension and due to the subject matter of this journal, only a few samples have been cited in literature and painting, bearing in mind that there are other examples in architecture, sculpture, music, dance and cinema.

In literature, references to pandemics and epidemics, generally plague, in different classical and modern texts can be easily found. In the fifth century B.C. Thucydides, father of scientific historiography, and Sophocles made references in their works to the plague that devastated Athens2. The Decameron, written in 1352 by Boccaccio, begins with a description of the bubonic plague that struck Florence in 1348 and how a group of ten young people fleeing from the plague, take refuge in a villa on the outskirts of Florence3-5.The diseases that devastated London during the 16th century are reflected in Shakespeare's plays; in Romeo and Juliet the plague and the quarantine of Verona play a crucial role6. Daniel Defoe in A Journal of the Plague Year which relates the Great Plague of London (1665) describes situations that seem to be current nowadays because they are so similar7. The Plague, by Albert Camus published in 1947, tells the story of some doctors who discovered the sense of solidarity in their humanitarian work in the city of Oran while it was struck by an epidemic of plague; the text begins with a quote from the aforementioned Defoe: " It is as reasonable to represent one kind of imprisonment by another as it is to represent anything that really exists by that which exists not" 7).

In paintings there are numerous samples of infectious diseases (plague, leprosy, tuberculosis and syphilis, etc.) and the fear they caused in the population and their socio-cultural implications. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, Dürer 1498; St Roche Among The Plague Victims and The Madonna In Glory, Ponte Basano,1575; The Plague of Asdod, by Poussin, 1630; The Plague of Athens, by Sweerts, 1652; Market Square, the plague of Naples, Gargiulo,1656 and Plague hospital( plague ridden) Goya in 17988 are some examples.

Medical texts on epidemics and pandemics (plague)

Medical historians such as López Piñero9or Sánchez Granjel10, among others, include in their works authors whose texts contain hidden titles and chapters dealing with plague and epidemics.

Until the 16th century, we can highlight: The Ebers papyrus that mentions some pestilential fevers that devastated the population from the margins of the Nile around the year 2000 B.C; probably the text in which the oldest reference to a collective suffering is made. Abu Ghiaphar Ibn Khatemar, an Arab physician from Almeria, described the epidemic that struck Almeria in 1347. Abu Mohamed Ben Alkhathib, an Arab physician from Granada, wrote in 1348 about the plague that struck this city; Guy Chauliac in 1363 wrote about the effects of the plague in Avignon and commented how parents did not visit their children, children did not visit their parents and how doctors did not risk visiting the sick because they were afraid of being infected.

In the 16th century, the development of printing press and medical humanism merged together what represented a turning point in the dissemination of books in general and especially medical books. We can highlight, among hundreds of texts available in digital libraries such as Dioscorides from the Complutense University or Cervantes Virtual, authors who refer in their texts to the bubonic plague, to its prevention and treatment, to collateral effects on society and psychology. We only have to type in their search forms the term plague, for the period 1501 to 1600 and in authors to identify titles like Regiment preservatiu e curatiu de la pestilencia written by Alcanys, 1490, Tratado util e muy provecho contra toda pestilencia and ayre corupto written by Fores in 1507, Information Book and cure of the plague of Zaragoza, and general preservation against the plague, written by Porcell in 1565, Remedios preservativos y curativos para el tiempo de la peste y otras curiosas experiencias written by Martinez de Leiva in 1597, De natura et conditionibus, praservatione et curatione pestis by Luis Mercado in 1598.

Lazarettos and other quarantine facilities

Nowadays disused facilities remind us that the isolation of infected people in remote buildings has existed throughout human history. They are not the current "Noah's Arks" or "Bubble Groups" or COVID hospitals, but some similarities can be established.

Until the end of the 19th century, maritime navigation was one of the main mechanisms for the spread of infectious diseases and a system for the expansion of epidemics and pandemics11. The passengers of some ships suspected to be infected by contagious diseases were confined to buildings for quarantine. Lazarettos were health facilities for the isolation, disinfection and care of people or animals infected or suspected of having an epidemic or contagious disease; they were quarantine stations1,11,12 Articles on the history of specific lazarettos, such as that Mahon one, remind us the existence of these confinement buildings13.

Other sanitary isolation, confinement or isolation facilities for infected people are the leprosarium (facilities, house or sanitary town destined specifically to provide healthcare to the patients of leprosy) (1 and the anti-tuberculosis sanatoriums (generally in mountain areas) like the one in Sierra Espuña in Murcia, the Royal Sanatorium of Guadarrama in Madrid, the Anti-Tuberculosis Dispensary of Raval in Barcelona. The document from the Carlos III Health Institute on sanitary architecture and tuberculosis sanatoriums 14) compiles detailed information on these buildings in Spain and Europe.

About Spanish flu

The 1917 Influenza pandemic, mistakenly called the Spanish Flu, is the most recent health crisis in history with the greatest health and socio-economic similarities to the current COVID-19. Articles about this pandemic were published in the main medical journals (The British Medical Journal and The Journal of the American Medical Association).Their authors already presaged future pandemics15.Alfonso Mendiola in “Crisis and history or Pandemic and Historiographic Operation” 16) provided a timely philosophical and historical reflection on the contextualization and/or decontextualization of the current COVID-19 crisis.

In The great influenza The epic story of the deadliest plague in history 17the author tells the epic story of the deadliest plague in history. The well-documented book is intended for physicians, scientists, health students, and historians as it combines health issues with science and politics. Understandably and convincingly written, it is a highly relevant book for the present times of COVID-1918.

Gould19) also reviews Barry's text on pandemic influenza and highlights how the book is told from the perspective of scientists and political leaders. Personal stories are told, about intuition, physicians and scientists who fought tenaciously the disease with science. It describes the 2 principles applied at the time: to explore epidemiology and to track clues in the laboratory.

For Wei20, 2019 coronavirus disease is the greatest public health crisis since the 1918 influenza pandemic and represents, as it did then, an unprecedented global threat.

OBJECTIVE

To map the production of knowledge about the history of pandemics; to check whether literature reviews in the field of pandemic nursing, and especially COVID-19, reflect historical background, specifically to episodes prior to the 21st century.

METHODOLOGY

A narrative and descriptive literature review has been carried out; online, digital or virtual libraries have been consulted for the history and conceptual framework, looking for the terms plague and epidemic as descriptors; the online dictionary of medical terms of the Royal Academy of Medicine of Spain was consulted.

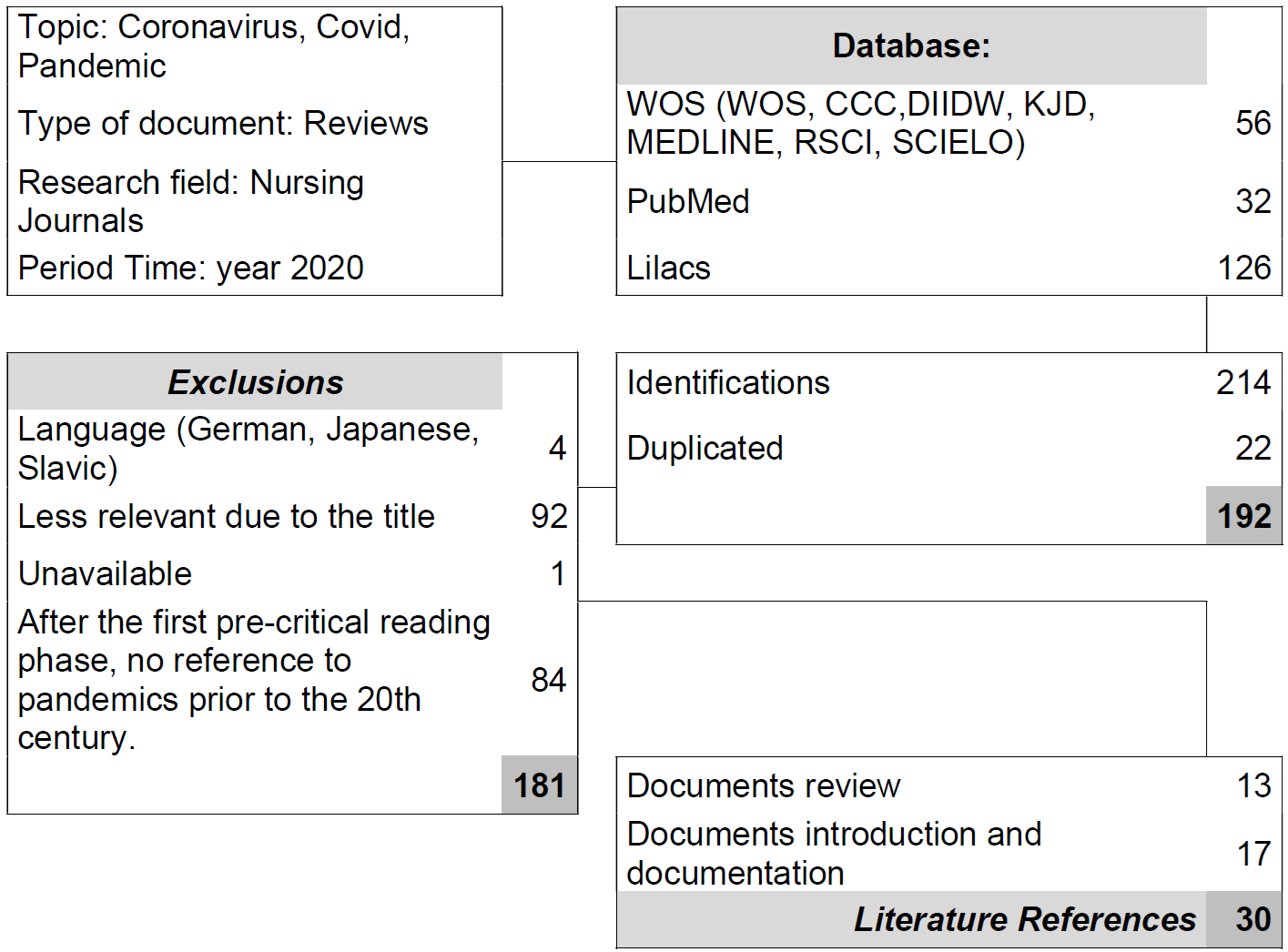

The Website of Science (WOS), PubMed and Lilacs were consulted for the review, with the terms COVID, Coronavirus and pandemic for reviews published from 2020 in the nursing field. The inclusion criteria were literature reviews on pandemics in general and COVID-19 in particular in the nursing field published since 2020, as well as other literature beyond this time frame, relevant to the subject under study. Documents in Japanese, German, Danish or Swedish were excluded; those that, despite dealing with pandemic subjects or COVID-19, did not mention historical antecedents to pandemics prior to the 21st century. A document was excluded because it could not be recovered. The WOS, the Virtual Library of Murciasalud and Google Scholar have been used to recover documents (See Table 2: flow diagram). The bibliographic management software EndNote x7 personal license and EndNote Web through the University of Murcia were used.

RESULTS

Historical research has identified a wealth of literature to base the most remote history of a pandemic. It was difficult to filter out such a wealth of information that is why only documentary threads for a more in-depth study of pandemics in humankind have been reflected in the introduction.

The literature review identified 214 reviews, 22 were duplicated. 185 were excluded due to language, relevance, and availability.11 reviews were analysed, trying to identify references of previous pandemic episodes or consequences of previous crises due to epidemics and pandemics.

Considering the pandemic’s origin

According to Nagib21) we are constantly invading the space of other living animals. That is not really news. We forget the history of other diseases that arose from animals that were domesticated in the Neolithic, more than 10,000 years ago. The era of agriculture emerged together with the domestication of wild animals.

Addressing impacts on health systems

For Keller 22 SARS-CoV-2 is an extraordinary event in the history of health care systems. It has had a rapid, universal, and powerful impact on the world, showing deficiencies in both the resilience of health care systems and the dissemination of best practices during an evolving situation.

Paterson23highlights the critical role of nurses in preventing the further spread of influenza and reducing the severity of the pandemic, which they consider to be the most devastating epidemic in history.

Daniela Savi 24 reminds us Nightingale in the present challenges of nursing management in the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the aforementioned article by Gould19on Barry's text17, S.Johnson 's book "The Ghost Map: The Story of London's Most Terrifying Epidemic"25tells the story of the cholera outbreak in Victorian London in 1851 that quickly became an epidemic and how it changed science, cities and the modern world. He creates a realistic account of life during that time while describing the efforts of the medical community to track the disease applying scientific methods and a persistent detective work, a model that still serves to public health providers today. He tells about a committed physician who tracked the disease without modern epidemiological tools.

Another article by Gould26, which has not been possible to consult because it was not available in the resources used, discusses the learning and standards of care in the COVID-19 disease.

Attention to side effects

Usher27) comments that throughout history, they have caused enormous loss of life and, as a result, have generated extreme social suffering.

For Wei, (20 the COVID-19 pandemic is the greatest public health crisis since the 1918 influenza pandemic and represents an unprecedented global threat.

Other documents of interest

Because of the small number of relevant results found, we propose the reading of some relevant documents.

Mirzaie28carried out a review of the narrative literature on the options of traditional medicine for the treatment of COVID-19.

Roney29describes the need to analyse the sequelae of COVID-19, with unprecedented effects in history, as it evolves and continues in the coming years.

For Rosa W30, nurses are leaders in patient care, education and care science. She analyses how environmental factors, psychosocial characteristics and interpersonal relationships affect the well-being of nurses and comments how their levels of burnout and job satisfaction are affected by environment.

CONCLUSIONS

Even if the subject of an article or review is a specific epidemic or pandemic, it may be relevant to reflect historical facts and ancient literature in order to have knowledge and evidence that these health crises have been repeated throughout human history.

On the other hand, it is important to substantiate an opinion. The current pandemic is not an invention; today we have more scientific evidence than three decades ago and we can see that human race has already experienced multiple epidemics and pandemics in history. Forgetting the past can be the reason to repeat some historical facts.

With the relevance of the documents, we have proven that, once more, a health crisis in the form of a pandemic is once again devastating human kind.

Since there is a lack of a minimal historical perspective in most of the mapped reviews, we advocate that articles and literature reviews on COVID-19 or other pandemics reflect, or at least mention, literature referring to previous pandemic crises.

If scientific evidence is essential in health care and in research, memory or historical evidence is necessary.

Acknowledgements

Health care professionals have been, are and will be at the forefront of the battle against the 'plague'.

REFERENCES

1. Real Academia Nacional ME. Diccionario online de términos médicos de la real Academia Nacional de Medicina de España [visitado 12/10/2020]. Accesible en: http://dtme.ranm.es/index.aspx. [ Links ]

2. Saravia de Grossi MI. Edipo rey de Sófocles: Una lectura del Estásimo IV. Argos. 2014; 37(2): 119-40. Accesible en: https://www.scienceopen.com/document?vid=81f13d7b-c2cf-4531-a553-6f87b9ec3468 [ Links ]

3. Cuadrada C. The spread of the plague: A sciento-historiographic review. Med Hist (Barc). 2015; (2): 4-19. Accesible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26399143 [ Links ]

4. Lombardi A. THE DEVIL IN THE FLESH: A READING OF BOCCACCIO'S DECAMERON. Alea-Estudos Neolatinos. 2012; 14(2): 180-200. Accesible en: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/alea/v14n2/03.pdf [ Links ]

5. Wigand ME, Becker T, Steger F. Psychosocial Reactions to Plagues in the Cultural History of Medicine: A Medical Humanities Approach. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2020; 208(6): 443-4. Accesible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32472811 [ Links ]

6. Paya E. Las enfemedades infecciosas en la obra de Willian Shakespeare. Revista Chilena De Infectologia. 2013; 30(6): 660-. Accesible en: https://scielo.conicyt.cl/pdf/rci/v30n6/art14.pdf [ Links ]

7. Guerard A, Sr. Looking Back in the Pages of WLT: OUR 1948 REVIEW OF ALBERT CAMUS'S LA PESTE. World Literature Today. 2020; 94(3): 69-. Accesible en: https://doi.org/10.7588/worllitetoda.94.3.0069 [ Links ]

8. Seoane Prado R. Las enfermedades infecciosas en el arte. Anales de la Real Academia Nacional de Medicina. 2018; 135(3). Accesible en: https://analesranm.es/wp-content/uploads/2018/numero_135_03/pdfs/ar135-rev12.pdf [ Links ]

9. López Piñero JM. Historia de la medicina universal. Valencia: Ayuntamiento de Valencia; 2010. [ Links ]

10. Sanchez Granjel L. Historia de la medicina española. Barcelona: Sayma; 1962. 205 p. p. [ Links ]

11. Ocaña Quevedo L. El Lazareto de Mahón. Medicina y Seguridad del Trabajo. 2007; 53(207): 63-9. Accesible en: http://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/mesetra/v53n207/original8.pdf [ Links ]

12. Rodríguez Toro JG, Pinto García R. La lepra. Imagenes y conceptos. Antioquia2007. 177 p. [ Links ]

13. Maldonado H, Hernandez M. Memorias de un sanatorio antituberculoso. Biomedica : revista del Instituto Nacional de Salud. 2004; 24 Supp 1: 27-33. Accesible en: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/bio/v24s1/v24sa05.pdf [ Links ]

14. Escuela Nacional S. Arquitectura sanitaria: sanatorios antituberculosos2014. Accesible en: http://gesdoc.isciii.es/gesdoccontroller?action=download&id=20/02/2015-5b9b4cb421. [ Links ]

15. Manrique-Abril FG, Beltrán-Morera J, Ospina-Díaz JM. Cien años después, recordando cómo BMJ y JAMA comunicaron la pandemia de gripe de 1918-1919. Revista de Salud Pública. 2018; 20(6): 787-91. Accesible en: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rsap/v20n6/0124-0064-rsap-20-06-787.pdf [ Links ]

16. Mendiola A. Crisis e historia o pandemia y operación historiográfica. Historia y grafía. 2020; (55): 173-5. Accesible en: http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/hg/n55/1405-0927-hg-55-173.pdf [ Links ]

17. Barry JM. The great influenza: the epic story of the deadliest plague in history. New York: Viking; 2004. 546 p p. [ Links ]

18. Palese P. The great influenza The epic story of the deadliest plague in history. The Journal Clinic Investigation. 2004; 114(2). Accesible en: https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI22439 [ Links ]

19. Gould KA. The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing. 2020; 39(3): 165-6. Accesible en: https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI22439 [ Links ]

20. Wei E, Segall J, Villanueva Y, et al. Coping With Trauma, Celebrating Life: Reinventing Patient And Staff Support During The COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Affairs. 2020; 39(9): 1597-600. Accesible en: https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00929 [ Links ]

21. Nagib Atallah A. COVID-19, evidências clínicas mais confiáveis. Os ensaios clínicos e as revisões sistemáticas. Daignostico y tratamiento. 2020; 25(2). Accesible en: http://docs.bvsalud.org/biblioref/2020/07/1115994/ok-rdt_252edit_alvaro-atallah.pdf [ Links ]

22. Keller KG, Reangsing C, Schneider JK. Clinical presentation and outcomes of hospitalized adults with COVID-19: A systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2020. Accesible en: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/jan.14558 [ Links ]

23. Paterson C, Gobel B, Gosselin T, et al. Oncology Nursing During a Pandemic: Critical Re flections in the Context of COVID-19. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2020; 36(3). Accesible en: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2020.151028 [ Links ]

24. Geremia DS, Vendruscolo C, Celuppi LC, et al. 200 Years of Florence and the challenges of nursing practices management in the COVID-19 pandemic. Revista Latino-Americana De Enfermagem. 2020; 28. Accesible en: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S0104-11692020000100403&script=sci_arttext [ Links ]

25. Johnson S. The ghost map : the story of London's most terrifying epidemic * and how it changed science, cities, and the modern world. New York: Riverhead Books; 2006. 299 p. p. [ Links ]

26. Gould KA. IHI Virtual Learning Hour Special Series: COVID-19 and Crisis Standards of Care. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing. 2020; 39(6): 351-2. Accesible en: no disponible [ Links ]

27. Usher K, Jackson D, Durkin J, et al. Pandemic-related behaviours and psychological outcomes; A rapid literature review to explain COVID-19 behaviours. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020. Accesible en: https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12790 [ Links ]

28. Mirzaie A, Halaji M, Dehkordi FS, et al. A narrative literature review on traditional medicine options for treatment of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2020; 40: 101214. Accesible en: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101214 [ Links ]

29. Roney LN, Beauvais AM, Bartos S. Igniting Change Supporting the Well-Being of Academicians Who Practice and Teach Critical Care. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America. 2020; 32(3): 407-19. Accesible en: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnc.2020.05.008 [ Links ]

30. Rosa WE, Davidson PM. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): strengthening our resolve to achieve universal palliative care. International Nursing Review. 2020; 67(2): 160-3. Accesible en: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/inr.12592 [ Links ]

Received: November 17, 2020; Accepted: October 11, 2020

texto em

texto em