Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Enfermería Global

versão On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.21 no.66 Murcia Abr. 2022 Epub 05-Maio-2022

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.490281

Originals

Relationship between sexuality and acute myocardial infarction from a phenomenological perspective

1 Magister en Enfermería. Profesor a tiempo completo e Instructor. Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia, Bucaramanga, Colombia. claudiaj.nino@campusucc.edu.co

2 Magister en Enfermería con énfasis en salud cardiovascular. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Colombia.

Introduction

Sexuality has been present throughout the life of the human being including aspects such as sexual activity, identity, roles, orientation, eroticism, etc. People who have suffered an Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) sexuality is affected by psychological, physical and even social factors. Therefore, the main purpose of this research is to describe the meaning of sexuality from someone has suffered AMI from a phenomenological perspective.

Method:

Qualitative study with a phenomenological approach, which sample consisted of 19 people who suffered acute infarction of the myocardium and who were treated by the emergency department or internal medicine of an institution of fourth level of complexity in the city of Bucaramanga (Colombia). In-depth interviews were applied and coded using the Atlas.ti 6.1 version. The analysis was carried out using the Colaizzi model.

Results

The sexuality of the person who has suffered an acute infarction of the myocardium is associated with multiple situations that are not only related to the sexual act. It is also linked with the emotional relationships such as, sharing with their partner, family, and friends. It shall be understood that this experience triggers negative and positive aspects that could affect the sexual expression or enhance it.

Conclusions

The meaning of sexuality for a person who has suffered acute infarction of the myocardium is given by emotions, care, education, beliefs and changes in sexuality, which impact patient’s process of recovery from their disease and their quality of life.

Keywords: Sexuality; sexuality meaning; Myocardial infarction

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines sexuality as a central aspect of the human being that is present throughout someone’s life including; sexual activity (SA), identities, gender roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy and reproduction. Which can be expressed by thoughts, fantasies, desires, beliefs, attitudes, values, behaviors, practices, roles and relationships 1. Although sexuality can include all these dimensions, not all of them are experienced or expressed. In the case of being partially or totally manifested. They will improve the quality of life by strengthening the immune and cardiovascular system, mental health, personal relationships and family bounds2.

Meanwhile, statistics at a global level including Colombia show that acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality which manifests itself with more frequency in young people with an active sexual life. Therefore, it is considered a public health problem due to the personal, economic and social repercussions made thereunder3. Indeed, people who are at risk of suffering or have suffered an AMI see their sexuality affected by physical and psychological changes that completely impact their AS. Revealing alterations in the dynamics of life of both the person who is suffering it as well as their partner and even their immediate family members affecting patient’s quality of life 4.

Generally speaking, a person who suffers AMI will stop expressing their sexuality since the concept is usually attributed to the intercourse. However, patients would not consider that sexuality is also related to the social, emotional and affective self. Patients put sexuality aside causing stress and psychological symptoms5,6. According to Casado Dones et al 7. the experience of one's own sexuality is an intimate, private and partially shared event that can be influenced by a multitude of physical factors (age, sex, health status, disabilities, drugs), educational factors (lack of knowledge or beliefs), religious, moral, household-level factors (the existence of a sTable or an occasional partner), mental (depression, grief, fear), social (a sexual patterns that are frowned upon), among others.

Similarly, different studies performed internationally 8)(9)(10)(11suggest that the patient with AMI presents difficulties in expressing their sexuality and that these changes do not have an organic origin. Consequently, the changes presented in the dynamics of SA have a more psychological context. The patience will experience a sense of concern and fear of suffering a heart attack again after AMI not to mention the alteration in their body image, idea of feeling less attractive, decreased self-esteem or some unpleasant symptoms such as shortness of breath, dizziness, chest pain, sweating, etc., All of those symptoms ultimately lead to a decrease or cancellation of the AS 12.

Additionally, the lack of attention to issues of sexuality by the healthcare workers after AMI can increase patient’s negative psychological symptoms causing him to look for information on the internet or consulting unqualified people to give them some orientation regarding sexual matters. This phenomenon can lead to abandonment of SA or complications arising from inadequate management of the patient’s follow-up. Likewise, the lack of information can compromise adherence to pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments and it is associated with worse overall clinical outcomes and resulted in the greatest decrease in quality of life5)(6)(7)(13 .

Taking into account the above mention and reviewing the phenomenon that addresses the issue of post-heart attack’s sexuality, specifically sexual activity, no updated information is evidenced. That being the case, the objective of this research is to describe the meaning of sexuality for the person who has suffered AMI from a phenomenological perspective.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

The present study is a phenomenological qualitative research with a Husserlian approach that allowed us to describe the meaning of people with AMI and its sexuality based on life experiences14. For the analysis, the Colaizzi approach was selected as the qualitative strategy that facilitates a deeper description of the phenomenon studied 15. This method involves seven steps:

1. Read all the descriptions,

2. From each description, take the most significant data and formulations and eliminate similar information.

3. Formulate the meaning by describing what each phrase said.

4. Establish a code for each phrase.

5. Separate the codes into subcategories that will help us with the construction of categories. Codes, subcategories and categories were validated with the participants during the study in each transcribed survey making it possible to determine if there was something in the description of the meanings that had not been taken into account.

6. Develop an exhaustive description of the phenomenon from all the previous processing.

7. Go back to the participants so that they recognize that the description included their meaning. Comments were included in the end of each description.

The selection of the participants was carried out intentionally and the sample consisted of 19 participants with whom theoretical saturation was achieved. The inclusion criteria took into account patients who suffered AMI with or without the ST-segment elevation. Patients who had more than a month of being out of the health institution that were over 18 years old and at the time of participating and they were not under the influence of drugs or substances that will not allow them to communicate.

In-depth interviews were applied to collect the information and guiding questions were used to prove how the experience of sexuality was developed after the AMI. Prior to the implementation of the interviews an informed consent was received and explanation of the objective of the study was made. Patients were told that interviews could be suspended or withdrawn at any time. In the same way, the following instructions were read aloud to each one of them: "On your own words describe sexuality after having to suffered an AMI”. From your experience explain what is sexuality for you. Would you like to make a contributing in terms of suggestions or changes?"

Interviews were conducted the first and third months after the patient's discharge from the hospital so that the informant could experience the phenomenon described in this study and could contribute to a certain extend from his experience. Interviews were held at patients’ houses, although they were arranged by phone for those patients who wanted to participate in the study with an appointment and from which the hospital's Ethics Committee provided a contact database. In addition, support from the area of clinical psychology Cooperativa de Colombia University was offered in case of any emotional alteration in the participants which at the end was not required.

The analysis of interviews was recorded and later transcribed into Microsoft Word the same day they were conducted. Subsequently, they were converted to PDF and taken to the Atlas.ti program licensed by Cooperativa de Colombia University. Interviews were stored and coded by number of participants and number of interviews carried out, following the sequence User 1 - Interview 1 (paragraph 1, line 2) U1-E1 (1: 2).

To maintain methodological rigor this research had the criteria of credibility, auditability and transferability16. In the same manner the research was classified with minimal risk and maintained the ethical aspects for studies in human beings as contemplated by Resolution 008430 from 1993 in Colombia. It should be clarified that there was no any type of intervention or manipulation of behavior in the individuals and that the necessary means were applied to protect the rights and well-being of the patients. The research was approved under the guidelines of the Council of International Organizations of Medical Sciences and by the Ethics Committee of the Cooperativa de Colombia University through the act No. INV2660 of 07-23-2019 and of the fourth level hospital of the city of Bucaramanga (Colombia).

RESULTS

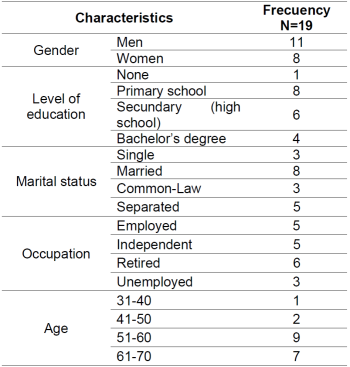

The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants in the research are shown in Table 1. Participants’ age is ranging between 50 and 70 years old (51-60 on average) most of which are men.

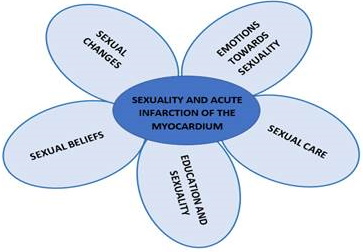

Based on the interviews performed with the patients and their respective analysis a diagram was constructed (Figure 1). This diagram synthesizes the description of the meaning of sexuality after facing an AMI. This meaning includes dimensions such as emotions towards sexuality, sexual care, education and sexuality, sexual beliefs and sexual changes.

Emotions and sexuality

This category refers to the emotions that are manifested in the person after an AMI especially because they experience negative emotional changes that are permanently expressed and externalized. In this way, patients would feel cautious or fearful, which prevents them from fully enjoying sexuality and causing frustration which alters their excitement, orgasm and therefore affective, personal and social relationships.

These emotions are expressed differently by every single person. The majority showed sadness, melancholy, loneliness, isolation and helplessness, factors related to feeling not completely useful during their convalescence process or in relation to poor performance during SA with their partner or sexual partner.

“I have not had a sentimental life because all that scares me… because I don't know if with whom I am going out and then having sex with would work. How can I say this? That is very frustrating. That happened to me in the beginning and because of this you start thinking “This will no longer work and what is left is just the 50% of it “That generates me sadness, like melancholy and I would end up isolating myself from everything partner, family, friends …” U10-E10 (10: 31-33).

However, these emotions change as the days go by allowing the reestablishment of affective relationships with the partner, family or friends. Feelings such as affection and love can arise when feeling loved which is important for the recovery process and the early reestablishment of AS as a key element for the beginning of a new life. Similarly, the participants consider other alternatives to express sexuality, such as hugs, massages, kisses, among others.

“At first when I had a heart attack, I thought that things were not going to improve and that I was never going to fully recover and that sex was going to take the back seat. However, with my rehabilitation I realized that everything was improving; the relationship with my partner, friends, family was a new beginning for me ... Ah, of course, so I was also looking for a way to have contact with my partner, a hug, a massage, kisses ... those expressions of affection and love are like a different way of expressing sexuality” U19-E19 (7:14).

Sexual care

This category refers to the necessary care provided by the partner, family and friends that in the early stages help to cope with the personal and sexual changes to which they have been subjected as a result of their AMI and during the adaptation and recovery. The initial changes are sudden and unexpected and they have a negative impact on the expression of sexuality that is just assumed from the physical component neglecting other elements that are also relevant such as expressions of affection, personal relationships, family and friends.

“I think to myself this is not going to fail… the economic expenses that I did not have budgeted and that were unexpected by the time of the heart attack ... There are things we cannot control ... then I think that I can lose my home by failing in the sexual part, and economical part as well. Thoughts come to mind, and a woman can leave you for that…” U17-E17 (5:14).

The care provided during the initial stages both physically and emotionally are necessary and they are a significant rewarding for the patient’s self-esteem which is why it fills the person with strength to achieve recovery and at the beginning of AS. This also affects the reestablishment of family and social relationships improving the quality of life. Therefore, it should be noted that within the care provided is the accompaniment, expressions of affection, interest and concern from the family, friends and individual and lifestyle changes also impact person’s well-being.

“With my family, friends, I have received good answers. They have played a major role in all of that. They have given me lots of love, I think, the care they have given me has helped me improving my health and allowing me to open myself to the world again. To me it felt like to be born again” U13-E13 (1: 5).

Education and sexuality

This category refers to the need expressed by most of the participants for a sexual education issue after the coronary event which must be given before discharge from the hospital, either by the specialist doctor or by the professional nurse. The participants emphasize that the education received is mostly focused on basic health care matters such as diet and exercise, but that very few health professionals discuss issues about sexuality which does not allow the early reestablishment of SA. The most frequently mentioned questions were related to the time in which they can restart AS if they can take pills to improve sexual performance. The duration of AS and whether or not they can reach orgasm due to increased arousal and the risk of new heart attack, among others. This leads to people looking for information in unreliable sources such as the internet, friends or other sources of information which can increase the risk of associated complications such as abandonment of pharmacological treatment, non-attendance at medical and health controls, etc.

“I would have liked that the nurse and the specialist doctor who treated me had given me information on this subject because I had doubts such as whether I can continue taking pills, whether it is normal for me to have erection problems or if it was more mentally related. I don't know. I would have like this to be part of the hospitalization ... because to be honest the one who told me about these things was a friend of mine and that's why I'm still afraid of being with the girl I like” U12- E12 (12:24).

Sexual beliefs

Beliefs about sexuality are seen differently by men and women: men are more focused on genitality and contact while women are more emotional, they value a good company and feelings.

“But if suddenly I cannot have sex, then they will start to go back ... Women look at sexuality from a different point of view from how men do. For them it is more a physical thing. They are more given to sex while we women are more into feelings and a good company” U15-E15 (3: 11-15).

Therefore, beliefs about sexuality in most cases are associated with the sexual encounter that allows establishing a strong bond with the couple which is necessary to live and enjoy with the partner. Thanks to the fact that sharing and establishing contact generates them emotional stability, accompanied or not by feelings such as love and affection which is essential to be in tranquility.

“For me, sexuality is being able to be with my partner the enjoyment of being together. Is about being able to express my feelings to another person. Something that gives me emotional stability, tranquility. It gives me the strength and motivates me to move forward. Is about sharing with people, sharing with family, sharing with the children” U13-E13 (1:26).

Similarly, some consider that the close relationships with family, friends and health personnel are part of this concept since this allows them to share and have greater emotional stability. This strengthens their relationships and they are more fruitful and they are associated with a lower risk of complications during sexual intercourse.

"Sexuality for me is like an enjoyment. The enjoyment of the person and beyond that the approach with other people to live in a pleasant state. I believe, that people enjoy to the fullest and reach a point of satisfaction not only in a relationship but also sharing with others like my family, friends, is about feeling good and strengthening these emotions with them” U7-E7 (7:32).

Sexual changes

In sexuality the changes that these people with AMI go through are personal, relationship, familiar and social related. These changes tend to be abrupted and expected and appear mainly in the initial stages after the coronary event.

"Well, my sex life after the heart attack changed for better and for worse ... for better because they take care of you when you are sick... and they are pending on you definitely and for worse because I became obsessed with the fact that something could happen to me, and that maybe could not be function as good as I used to” U8-E8 (8:42).

Among the personal changes, the participants expressed modifications in SA due to feelings of fear that the arousal complications may occur, for this reason they delay or ultimately, they avoid having SA. On the other hand, there are positive changes that are associated with healthy lifestyles, such as having a good diet, doing regular physical activity, reducing stress and alcohol consumption, among others.

"It has affected me considerably I mean I get depressed because I feel that I am not going to be able to satisfy her in the masculine way. It affects me a lot, so that has affected me as it is not like before" U10-E10 (10: 22-26).

“So, I have been trying to improve all the eating habits, walking, exercising, relationships with the family, with brothers, with mother, I mean to take more time for yourself, right now I am calm, I do not stress, I try not to fight at work with the employees, and to take things easy with my wife” U8-E8 (8: 32-34)

On the other hand, partner changes are given by adjustments in the dynamics prior to AMI so they replace contact and genitality as a form of expression to focus on intimacy based on kisses, soft caresses, massages, and some others. In the same way, they consider that this change in dynamics have strengthened their relationship in most cases. However, in some case scenarios specially for women they considered that the event was the breaking point of the relationship since men are less comprehensive initiating the AS and they would look for other healthy partners with whom they can have sex.

"My husband is now more affectionate, more attentive ... Ah and he did change. Before he was affectionate, but now he is even more ... Now I feel more attracted to him. I feel that now everything has improved. We change our way of seeing sexuality. I would think that now we see it more of a mutual enjoyment but not just sex it is more for company, love, and some other things” U18-E18 (6:10).

“Some men think that if the woman had a heart attack, they will end up the relationship because they cannot live without sex. They must have a person to have sex with” U15-E15 (3:10).

Regarding household relationships participants expressed that they experienced processes of isolation and loneliness during the first three months. Once the mourning was over, they were open to interaction and recognized in the process that they had a family and friends who showed concern, support and strengthened the recovery process which ultimately generates trust, happiness and comfort.

“Well, at first you isolate yourself, especially because of what I was telling you. You are scared of everything… but after a while you realize that your family, some friends, not all, have given you that support, affection, care, help that for me has been something important for my recovery. It has given me enough confidence to start again” U7-E7 (7:48).

DISCUSSION

The human sexual response is for the participants a multidimensional aspect where intercourse and contact predominate. However, at the same time they include the emotional bond as an important component for the expression of sexuality. This is how the bond covers important and necessary aspects such as company and affection, expressed in different ways either through health care, understanding, tolerance, patience as well as close relationships with the family, friends and society. Therefore, these results allow us to see this phenomenon from another perspective which complements what was found in other studies in which physical alterations are related to libido, difficulty in erection, ejaculation disorders and impotence due to age, diseases predominate. In addition, anxiety, fear of intercourse and lack of information 9)(10)(17, making it necessary for people who have suffered AMI to receive effective sexual counseling.

On the other hand, the negative emotions generated in the person after AMI are related to the changes at a personal and social level in which people are abruptly subjected. These emotions are represented by repetitive ideas of complications such as reinfarction or death leading them to self-isolation and prevent them from expressing sexuality in all its dimensions (coital, affective and relationships) in a healthy and early way. The above mention is also expressed by other studies 10)(13)(18)(19, where it is considered that emotions such as anxiety, fear and depression force the person to have changes in the behavior of the sexual pattern, hindering the social and sexual reincorporation and decreasing considerably the quality of life of people in a post-AMI state9.

Associated sexual problems such as impotence, premature ejaculation, decreased libido, the frequency and quality of sexual intercourse are associated with more emotional than physical problems or a combination of all of the above. This, added to the poor counseling by medical staff increases the risk of derived complications. The abandonment of pharmacological treatment or the abandonment of the sexual pattern which negatively affects the quality of life of people. Similarly, it was found that patients were not happy with their sexual life because they had complications during SA, such as premature ejaculation, orgasmic dysfunction, fatigue or dyspnea, which was associated with a new coronary event that can hinder, prevent or completely abolish AS restart 20)(21)(22 .

Participants also changed the way of expressing sexuality going from coital to other forms of contact such as hugs, massages, expressions of affection, love and care. These types of manifestations are necessary for recovery and are more satisfactory when provided by the partner, family or friends, a similar finding to what is proposed by Belizário Vieira et al. 23, who emphasize the importance of family support for adherence to treatment and the recovery of the patient which explains the protective effect of individual, family and social support as an antagonist of organized stress in the patient with AMI.

In the present study, sexual education provided by the health professional is important for the patient who has suffered an AMI and for his partner as a fundamental protagonist to restart the sexual life that he had before. Therefore, it is necessary to involve the couple in hospital discharge as this helps to reduce negative psychological symptoms associated with misinformation 24. In another study, with a similar context, it was considered that nursing professionals are a useful resource when establishing a therapeutic relationship with the patient. Thanks to the fact that they allow to clarify doubts, clarify prejudices and misconceptions that may alter sexuality as well as offering other therapeutical alternative mitigating the appearance of associated psychological symptoms 7,25. Similarly, the presence of nursing professionals facilitates the search for better solutions or strategies to strengthen sexual health and optimize patient’s quality of life 26)(27)(28)(29)(30.

In relation to the restarted time of the SA. Participants stated that it began between the first and third month after AMI but that it was performed with caution, which caused a decrease in the frequency of SA. These findings differ from those proposed by Alconero Camarero et al. 17, who point out that 44.4% of those interviewed in their research were aware of the recommendation to restart sexual activity from the second week after AMI. In the same study, a percentage of 9.3% believed that they would never be able to have sex again as a result of the event.

For the present study, a different result was found in the expression of sexuality between men and women after AMI. Consequently, women expressed greater sexual isolation, and psychological changes that affected their health as it was stated by McCall Hosenfeld et al. (31, who claimed that female sexual dysfunctions as psychosomatic disorders can appear permanently or temporarily in the sexual life of a woman and it could affect any of the phases of the sexual response: desire-excitement-orgasm and have a marked affective component and communication with the partner. For this reason, it is necessary for the nursing professional to recognize the sexuality of women as a fundamental element in the quality of life, understanding the meaning of sexuality, the influencing factors and the reality of sexual dysfunctions25 .

To summarize the experience of AMI in the person is manifested by symptoms that put the quality of sexual and psychosocial life at risk. This matches with what was stated by Zaranza de Sousa and Mendes de Oliveira 22, who argues that all the feelings that arise in the minds of patients at the time of a heart attack are the same generators of different fears and anxieties. Therefore, they deserve attention because of the high risk of generating emotional shocks and stress which makes them qualify to receive help from health professionals.

CONCLUSION

The meaning of sexuality for the person who has suffered AMI is guided by emotions, care, education, beliefs and changes in sexuality which impact the recovery process from their disease and quality of life. The emotions experienced by the person after the heart attack are generally fear and negative ideas related to the initiation of sexual activity as well as they experience erectile dysfunction and decreased libido, which generates concern and a need for professional help since their self-esteem and self-confidence are compromised. Therefore, it is important that the nursing professional from undergraduate programs recognize the experience and training in these issues so that they can easily develop communication with the patient when these circumstances are involved, identifying causes, taking the initiative and planning strategies to solve these problems from the intervention of the interdisciplinary team.

Recommendations when describing the meaning of sexuality for the person who has suffered AMI showed that it is necessary to consolidate knowledge and tools that allow strengthening holistic care in sexual counseling after hospital discharge and cardiac rehabilitation. Likewise, it is recommended to establish an effective communication channel by monitoring the person who has suffered AMI through an interdisciplinary team, so that understanding, interest and support can be demonstrated as a respond to the needs of the patients.

A program development is suggested within the educational goals in each institution aimed at the nursing staff that allows improving skills and security for counseling in the field of sexuality. It is also recommended to develop a management guide for sexual counseling for hospital discharge and one for the continuation in cardiac rehabilitation. A final recommendation is to continue conducting research in the sexual field that will enrich nursing practices such as the measurement of satisfaction with nursing care in sexual counseling for people with AMI.

Founding:

This article is the result of the research "Meaning of sexuality in the person who has suffered acute myocardial infarction", funded by Cooperativa de Colombia University. .

REFERENCES

1. Organización Mundial de la Salud. La salud sexual y su relación con la salud reproductiva: un enfoque operativo [Internet]. 2018 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021]. p. 12. Disponible en: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/274656/9789243512884-spa.pdf [ Links ]

2. Olivera Carmenates C, Bujardón Mendoza A. Estrategia educativa para lograr una sexualidad saludable en el adulto mayor. Rev Hum Med [Internet]. 2010 [citado el 10 de agosto de 2021];10(2). Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1727-81202010000200006&lng=es&nrm=iso [ Links ]

3. Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Análisis de Situación de Salud (ASIS): Colombia, 2018 [Internet]. 2019 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021]. p. 274. Disponible en: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/VS/ED/PSP/asis-colombia-2018.pdf [ Links ]

4. Stein R, Sardinha A, Araújo CGS. Sexual Activity and Heart Patients: A Contemporary Perspective. Can J Cardiol [Internet]. 2016 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];32(4):410-20. Disponible en: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0828282X15015019 [ Links ]

5. López González Y. Particularidades del desempeño sexual en pacientes con Cardiopatía Isquémica. Duazary [Internet]. 2005 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];2(1):11-8. Disponible en: http://revistas.unimagdalena.edu.co/index.php/duazary/article/view/279 [ Links ]

6. Lindau ST, Abramsohn EM, Bueno H, D'Onofrio G, Lichtman JH, Lorenze NP, et al. Sexual Activity and Counseling in the First Month After Acute Myocardial Infarction Among Younger Adults in the United States and Spain. Circulation [Internet]. 2014 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];130(25):2302-9. Disponible en: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012709 [ Links ]

7. Casado Dones M aJ., de Andrés Gimeno B, Moreno González C, Fernández Balcones C, Cruz Martín RM., Colmenar García C. La sexualidad en los pacientes con infarto agudo de miocardio. Enfermería Intensiva [Internet]. 2002 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];13(1):2-8. Disponible en: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1130239902780486 [ Links ]

8. Lugo Mata ÁR. Actividad sexual posterior a infarto de miocardio en pacientes de dos hospitales de Maturín, Venezuela: Agosto 2015 - Mayo 2016. Scientifica (Cairo) [Internet]. 2016 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];14(1):13-6. Disponible en: http://www.revistasbolivianas.org.bo/pdf/rsscem/v14n1/v14n1_a01.pdf [ Links ]

9. Díaz Cortina E. Actividad sexual en pacientes cardiópatas. Rev Mex Enfermería Cardiológica [Internet]. 2002 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];10(3):106-8. Disponible en: https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/enfe/en-2002/en023e.pdf [ Links ]

10. Steinke EE. Sexual dysfunction common in people with coronary heart disease, but few cardiovascular changes actually occur during sexual activity. Evid Based Nurs [Internet]. 2015 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];18(1):19. Disponible en: https://ebn.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/eb-2014-101787 [ Links ]

11. García Nicola Y. Evaluación de la aplicación de un programa de intervención psicológica en pacientes que han sufrido un evento cardiaco [tesis de maestría] [Internet]. Universitas Miguel Hernández; 2020. Disponible en: http://dspace.umh.es/jspui/bitstream/11000/5665/1/GARCIA Yovana TFM.pdf [ Links ]

12. Kalka D, Gebala J, Borecki M, Pilecki W, Rusiecki L. Return to sexual activity after myocardial infarction - An analysis of the level of knowledge in men undergoing cardiac rehabilitation. Eur J Intern Med [Internet]. 2017 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];37:e31-3. Disponible en: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0953620516303181 [ Links ]

13. Abramsohn EM, Decker C, Garavalia B, Garavalia L, Gosch K, Krumholz HM, et al. "I'm Not Just a Heart, I'm a Whole Person Here": A Qualitative Study to Improve Sexual Outcomes in Women With Myocardial Infarction. J Am Heart Assoc [Internet]. 2013 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];2(4):1-12. Disponible en: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/JAHA.113.000199 [ Links ]

14. Fuster Guillen DE. Investigación cualitativa: método fenomenológico hermenéutico. Propósitos y Represent. 2019;7(1):201-29. [ Links ]

15. Shosha GA. Employment of Colaizzi's strategy in descriptive phenomenology: a reflection of a researcher. Eur Sci J [Internet]. 2012 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];8(27):31-43. Disponible en: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/EMPLOYMENT-OF-COLAIZZI%27S-STRATEGY-IN-DESCRIPTIVE-A-Shosha/0d91d89244476162145584d13ac29cf85df5859d [ Links ]

16. Polit DF, Hungler B. Investigación científica en ciencias de la salud. 6a ed. Ciudad de México: McGraw-Hill Interamericana; 2000. 287 p. [ Links ]

17. Alconero Camarero AR, Casaus Pérez M, Gutiérrez Torre E, Saiz Fernández G, Pérez Bolado C. Evaluación de la información sobre actividad sexual proporcionada a pacientes con síndrome coronario agudo. Enfermería Intensiva [Internet]. 2008 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];19(2):78-85. Disponible en: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1130239908727482 [ Links ]

18. Lindau ST, Abramsohn E, Gosch K, Wroblewski K, Spatz ES, Chan PS, et al. Patterns and Loss of Sexual Activity in the Year Following Hospitalization for Acute Myocardial Infarction (a United States National Multisite Observational Study). Am J Cardiol [Internet]. 2012 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];109(10):1439-44. Disponible en: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0002914912004559 [ Links ]

19. Rodríguez Ricardo A, Torres Tamayo AM, Fernández Santiesteban VM. Estrategia de orientación educativa sobre el autocuidado en el adulto mayor con infarto agudo del miocardio. CCM [Internet]. 2019 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];23(4). Disponible en: https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/correo/ccm-2019/ccm194j.pdf [ Links ]

20. Altiok M, Yilmaz M. Opinions of Individuals Who have had Myocardial Infarction About Sex. Sex Disabil [Internet]. 2011 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];29(3):263-73. Disponible en: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11195-011-9217-5 [ Links ]

21. Parra Gil R, Lizcano Álvarez Á, Galván Redondo D, Guerra Blanco C. Infartapp: una app para los autocuidados en pacientes postinfartados. Enfermería en Cardiol [Internet]. 2019 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];16(76):83-8. Disponible en: https://campusaeec.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/ART_9_76AE01.pdf [ Links ]

22. Zaranza de Sousa M, Mendes de Oliveira VL. Vivenciando o infarto: experiência e expectativas dos pacientes. Esc Anna Nery [Internet]. 2005 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];9(1):72-9. Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1277/127720494009.pdf [ Links ]

23. Belizário Vieira M, da Silva Souza W, Freire Cavalcante P, Gonzaga Moura de Carvalho I, José de Almeida R. Percepção de homens após infarto agudo do miocárdio. Rev Bras em Promoção da Saúde [Internet]. 2017 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];30(3):1-9. Disponible en: http://periodicos.unifor.br/RBPS/article/view/5833 [ Links ]

24. Murphy PJ, Noone C, D'Eath M, Casey D, Doherty S, Jaarsma T, et al. The CHARMS pilot study: a multi-method assessment of the feasibility of a sexual counselling implementation intervention in cardiac rehabilitation in Ireland. Pilot Feasibility Stud [Internet]. 2018 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];4(1):88. Disponible en: https://pilotfeasibilitystudies.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40814-018-0278-4 [ Links ]

25. Achury D. Sexualidad en la mujer con enfermedad cardiovascular: un problema oculto. Rev Cuid [Internet]. 2011 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];2(1):225-9. Disponible en: https://revistas.udes.edu.co/cuidarte/article/view/61 [ Links ]

26. Rodríguez T, Navarro J, Moreno A, Castro C. La sexualidad del paciente con infarto agudo del miocardio en el marco de la rehabilitación cardiovascular. Sexol y Soc [Internet]. 2006 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];12(31):29-34. Disponible en: http://salutsexual.sidastudi.org/resources/inmagic-img/DD49374.pdf [ Links ]

27. Evcili F, Demirel G. Patient's Sexual Health and Nursing: A Neglected Area. Int J Caring Sci [Internet]. 2018 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];11(2):1282-8. Disponible en: http://internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org/docs/72_evcili_original_10_2.pdf [ Links ]

28. Karani S, McLuskey J. Facilitators and barriers for nurses in providing sexual education to myocardial-infarction patients: A qualitative systematic review. Intensive Crit Care Nurs [Internet]. 2020 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];58:102802. Disponible en: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0964339720300057 [ Links ]

29. Arikan F, Meydanlioglu A, Ozcan K, Canli Ozer Z. Attitudes and Beliefs of Nurses Regarding Discussion of Sexual Concerns of Patients During Hospitalization. Sex Disabil [Internet]. 2015;33(3):327-37. Disponible en: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11195-014-9361-9 [ Links ]

30. Rojas-Reyes J, Flórez-Flórez ML. Adherencia al tratamiento y calidad de vida en personas con infarto agudo de miocardio. Aquichan [Internet]. 2016 [citado el 6 de agosto de 2021];16(3):328-39. Disponible en: http://aquichan.unisabana.edu.co/index.php/aquichan/article/view/328/pdf_1 [ Links ]

31. McCall-Hosenfeld JS, Freund KM, Legault C, Jaramillo SA, Cochrane BB, Manson JE, et al. Sexual Satisfaction and Cardiovascular Disease: The Women's Health Initiative. Am J Med [Internet]. abril de 2008 [citado el 10 de agosto de 2021];121(4):295-301. Disponible en: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0002934307011783 [ Links ]

Received: August 26, 2021; Accepted: December 18, 2021

texto em

texto em