Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Enfermería Global

versão On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.21 no.67 Murcia Jul. 2022 Epub 19-Set-2022

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.488311

Originals

Evaluation of patient safety culture from the perspective of intensive care professionals

1West Regional Hospital - Chapecó - Santa Catarina – Brazil

2University of Paraná - Francisco Beltrão - Paraná – Brazil

4University of Fronteira Sul (UFFS) - Chapecó/ Santa Catarina – Brazil

Objective:

To evaluate the patient safety culture from the perspective of professionals who work in Intensive Care Units.

Method:

This is a descriptive, exploratory, cross-sectional study of a quantitative character. The sample consisted of 72 professionals, 31 nurses, 21 nursing technicians, 12 (physiotherapists, speech therapists, occupational therapists), 5 doctors, 2 psychologists, 1 nursing assistant who work in intensive care units in the southwest and northwest regions of Paraná and west of Santa Catarina. The data collection carried out between August and October 2020, via online electronic form, through the Google platform, using the questionnaire adapted to Research on Patient Safety in Hospitals. The data were tabulated in the Excel program and, subsequently, a descriptive analysis of the data was performed by using theStatistical Package for the Social Sciences software(SPSS 25.0).

Results:

Only 2 categories achieved more than 75% positive responses in relation to the unit's safety culture, namely: when there is a lot of work to be done, professionals work as a team to complete it and they are actively doing things to improve the patient's safety.

Conclusion:

From the perspective of professionals, patient safety is not effective yet, as in some aspects it needs to be improved as well as in other criteria, it is shown to be weakened.

Keywords: Intensive Care Units; Patient safety; Culture; Quality Inspection of Health Care; Health professionals

INTRODUCTION

Over the years, several events have raised great concern about Patient Safety (PS) and safety culture; however, the number of complications, Adverse Events (AE) and prevenTable deaths remain alarming1.

In Intensive Care Units (ICU), about 20% of patients can experience an AE, pproximately 40% to 45% could have been avoided2 3 4.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), PS is defined as “reducing the risk of unnecessary harm associated with health care to an accepTable minimum”2. The Patient Safety Culture (PSC) is composed of the following items: responsibility of leaders for safety, open communication, organizational learning, non-punitive approach to reporting AE, teamwork and shared belief in the importance of safety5,6.

The safety culture aims to prevent and to reduce risks to patients and encourage the reporting of incidents. The negative, punitive and fragile culture that generates fear and shame for professionals should not be incorporated into institutions7,8.

The global challenge to reduce AEs lies in changing the institution's safety culture and in the involvement and commitment of professionals and hospital management. Unsafe environment and care cause unnecessary risks to the patient, which can result in prolonged hospitalization, injuries, pain, falls, disabilities, dysfunctions and death. They also cause an increase in costs for the institution and a bad impression of the service, frustration and exhaustion of professionals, among other events9,10.

PS is considered a global priority, so studies have been developed in the area in order to reduce AEs, to improve the patient safety culture and the quality of care provided. Therefore, it is extremely important to produce knowledge for professionals and help institutions to recognize flaws and weaknesses in the work environment10. In view of the above, the problem question arose: what is the patient safety culture from the perspective of health professionals working in the ICU? Therefore, the aim was to evaluate the patient safety culture from the perspective of professionals working in Intensive Care Units.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

This is a descriptive-exploratory, cross-sectional research with a quantitative approach, developed online, through an electronic form composed of a questionnaire adapted cross-culturally and validated in Brazil, called the Hospital Surveyon Patient Safety Culture (HSOPSC) questionnaire, prepared by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ)11.

The questionnaire was made available through the link https://forms.gle/jyJt6UWiWyVvBtnQ6, through the Google platform, from August to October 2020, for the nursing directors and technical managers of the ICUs of the hospitals surveyed for dissemination among professionals working in this sector field.

The form covers 12 dimensions of the PSC and allows the assessment of the positive and negative aspects of the culture, with closed and open questions. Inclusion criteria were: health professionals of any age, gender and work shift, working in Adult and Pediatric ICUs in the Northwest and Southwest of Paraná, as well as in the West of Santa Catarina. Among the professionals: doctors, nurses, nursing technicians, nutritionists, speech therapists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and psychologists. As an exclusion criterion, it was decided not to include health professionals who were on vacation, leave or who did not accept to participate in the study, in addition to other professional classes, as well as those working in other sectors.

The sample selection was for convenience, upon acceptance of the Free and Informed Consent Term (FIC), by electronic means. The data were tabulated and their descriptive analysis was submitted to the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (SPSS 25.0). The questions referring to the dimensions studied in the instrument were exclusively known by the researchers, since the research participants were not identified, and the ethical and legal principles were preserved, according to Resolution 466/2012, of the National Health Council. It was approved by the Ethics Committee in Research with Human Beings of Universidade Paranaense - Unipar, according to opinion 4,053,787.

RESULTS

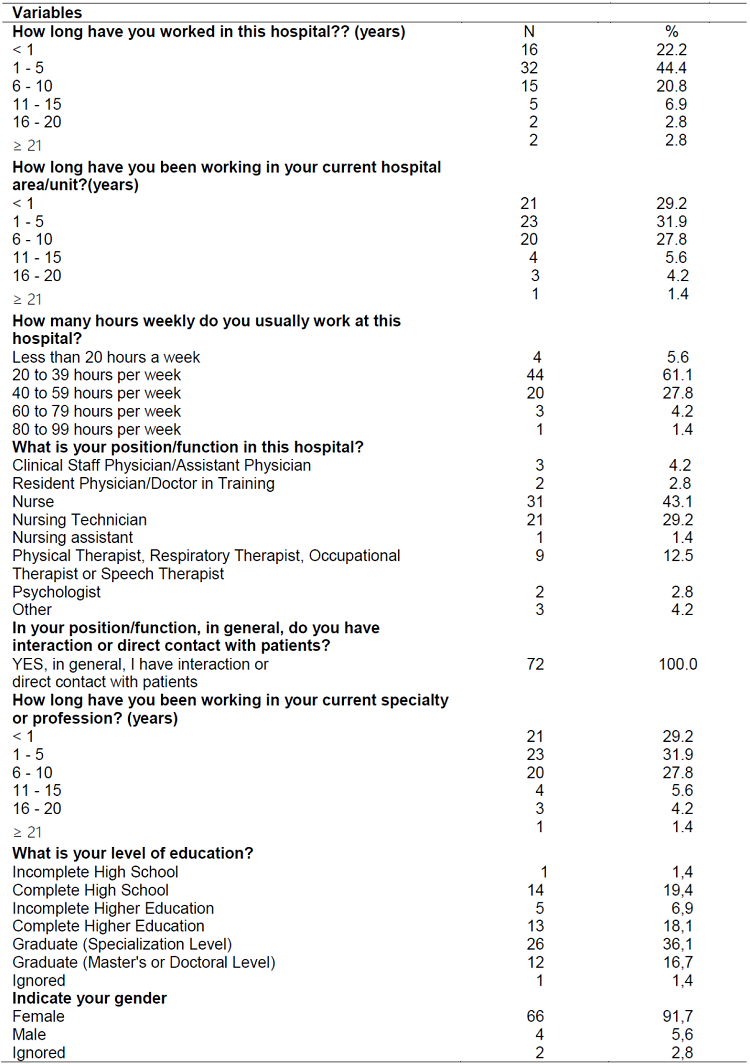

For better understanding, the data are presented in Tables and described based on the characterization of the participants.Table 1describes the profile of the study participants.

Table 1: General information about healthcare professionals. Brazil, 2020

Source: Research data, authors (2020).

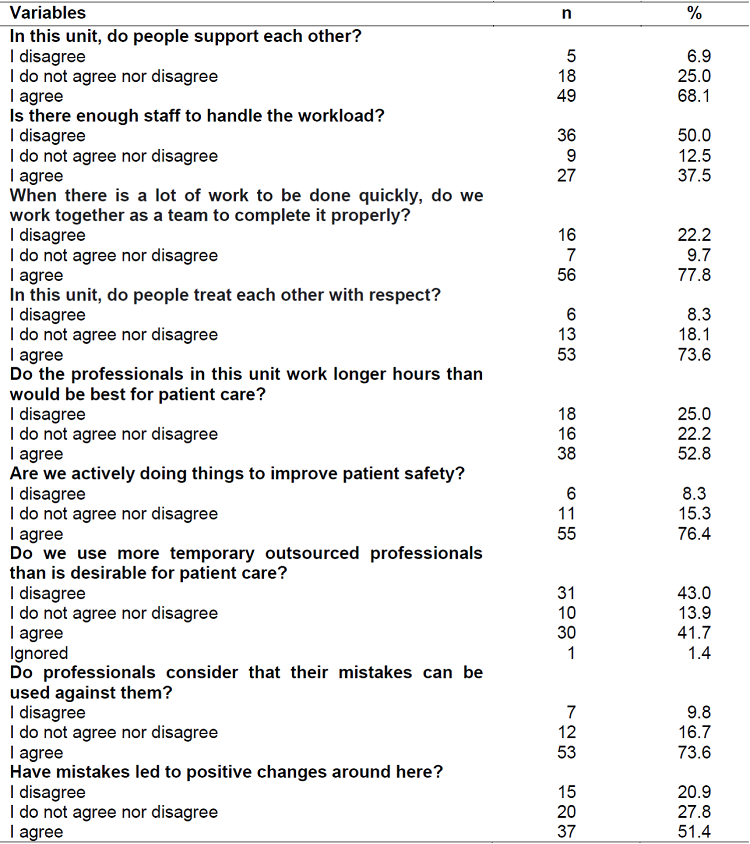

Regarding the aspects related to the work environment, considering the unit of work, the professionals agreed that people supported each other (68.1%); however, they disagreed about the sufficiency of personnel to handle the workload (50%). They pointed out that errors could be used against them (73.6%), but highlighted that the notification of errors motivated positive changes (51.4%).

With regard to the overload of the unit, 56.9% revealed collaboration between professionals. It is noteworthy that when an adverse event is reported, 70.8% of professionals agreed that the focus is on the person and not on the problem. Regarding professionals working in a “crisis situation”, trying to do too much and too quickly, 51.4% agreed with this statement.

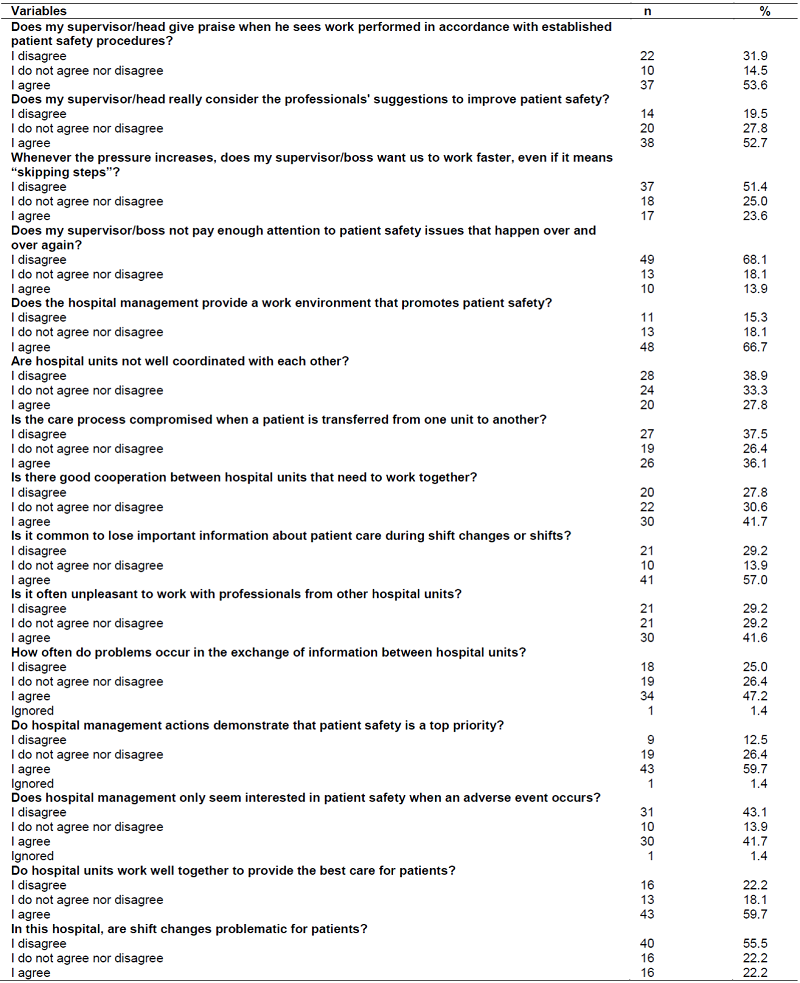

Table 2shows that 53.6% of the population surveyed agreed that the supervisor/head praised and accepted the suggestions for actions aimed at strengthening safe care. It was also observed that 41.6% said it was unpleasant to work with professionals from other hospital units. Most of the time, the professionals answered that there were problems in the exchange of information between the hospital units (47.2%).

Table 2: Perceptions of professionals on aspects related to the work environment, considering the unit of action. Brazil, 2020

Source: Research data, authors (2020).

Table 3: Professionals' perceptions of the supervisor/head of the hospital's work unit. Brazil, 2020

Source: Research data, authors (2020).

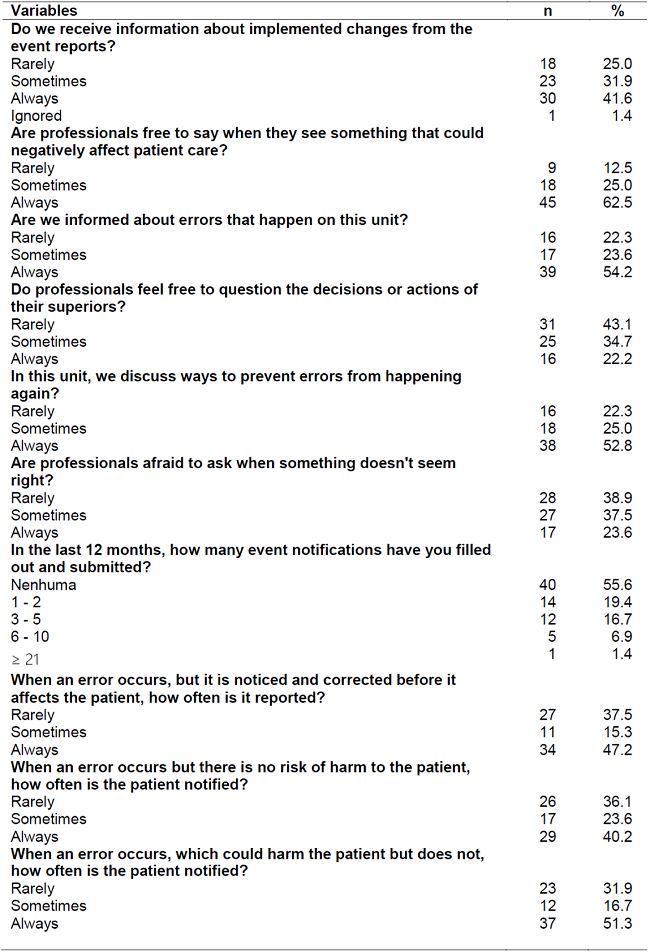

Table 4represents the data regarding the management of adverse events, the changes implemented and the communication between professionals working in the ICU. As for professionals being free to talk about something that could negatively affect patient care, the answer rarely stood out (62.5%).

Table 4: Data regarding the management of adverse events, the changes implemented and the communication between professionals working in intensive care units. Brazil, 2020

Source: Research data, authors (2020).

It should be noted that, for the most part, 54.2% of professionals were always informed about errors that occurred in the work unit. However, professionals rarely felt comforTable questioning superiors' decisions or actions (43.1%). In relation to the last 12 months, the answer “no notification” filled in and presented by the professionals participating in the research predominated (55.6%).

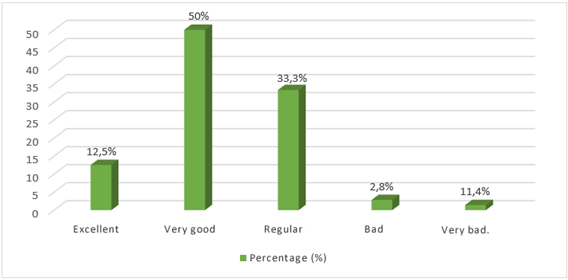

Regarding the patient safety assessment made by health professionals in the work unit, “very good” (50%) stood out, followed by “regular” (33.3%), “excellent” (12.5%), “very bad” (11.4%) and “bad” (2.8%), as shown inGraph 1.

DISCUSSION

Among the 72 professionals who participated in this study, a profile was found that points out positive and negative aspects related to the patient safety culture.

In this study, two dimensions obtained positive responses above 75%, classified as areas of strength for SP, as recommended by the AHRQ. Responses with a percentage greater than 50%, less than 75% are considered neutral, and areas with potential improvement are those with responses below 50%(1.12). In this study, results classified as neutral and areas with potential for improvement were found, with “neutral” responses prevailing.

Out of the 12 dimensions included in the instrument, two (75%) reached favorable responses to the safety culture, evidencing weaknesses in the organizational system that directly affect the quality of care offered to the patient. Asa sinequa nonrequirement, PS should be considered a priority in any health environment, especially in intensive care, as it is considered a space that houses critically ill patients who require highly complex and resolute interventions, in a short time, at the bedside13.

It is known that respectful and supportive relationships between professionals and teammates reduce conflicts and improve communication, contributing to the quality of care provided. Conditions that favor the promotion of the PS culture, as they reduce beliefs and judgments and improve the good relationship between the health team14,15. It is understood that the lack of professionals compromises patient safety, since the care provided in this way, seeking quantity and not quality, leaves the health professional overloaded, stressed and inattentive, favoring the development of AE8,9.

Working together reflects on shared responsibility for care, differentiated experience and knowledge, team unity, reduced conflicts and increased productivity. With a pleasant work environment and good communication between the team, benefits will be provided to PS16.

A study carried out in the southern region of Brazil, with ICU professionals, suggests an increase in the number of professionals, with a reduction in the workload and the weekly scale. Thus, it is reflected that in these units, professionals have an exacerbated workload and work exhaustively, due to complex procedures, serious patients and at risk of death5.

Good PS practices depend on a number of factors, among which are the workload and schedule compatible with legal recommendations and team capacity. It should be noted that many workers, as a result of low pay, end up working double shifts, greatly increasing the chances of error. Evidences corroborate that longs periods of care can lead to an increase in errors and AE, due to work overload, more than an employment relationship, to fatigue and exhaustion17,18.

The health of the worker and the PS are impacted by outsourcing, as a professional who is not well psychologically and physically will not provide fully safe care to the patients served. Outsourcing influences the implementation of a neoliberal model and the precariousness of work relationships19,20.

There are recommendations from the professionals of the health team to improve the PS, among these, it is important to carry out periodic training, develop and implement protocols, train new employees, prepare manuals on PS, correct inadequate practices of the service, increase the number of professionals, reduce the workload weekly hours, avoid shifts of less than 6 hours and more than 12 hours, minimize the turnover of professionals, improve the remuneration of professionals, promote equality of rights and duties among the team and implement regulations that regulate the behavior of professionals in the work environment5.

The professionals from the units surveyed agreed that errors can be used against them (73.6%). Health professionals disagreed on the dimension “it is only by chance that more serious errors do not happen” (45.9%), corroborating another survey that showed a disagreement of 38.6%. This can be explained by the lack of attention, work overload and stress in an ICU. The importance of performing EC/permanent and use of protocols is highlighted21.

When an AE was reported, professionals agreed that the focus was on the person and not on the problem or system (70.8%). Thus, confirming data from another survey that showed 82.46% of professionals believed that when an error occurs, they focus on the person who made a mistake1. With a negative and punitive safety culture in the institution, the chances of occurrence and underreporting of AE are increased, negatively interfering in the teamwork culture22,23.

Another aspect to be considered is the fact that 73.6% of the professionals were concerned that errors would be recorded in the job sheets. In health institutions, the punitive safety culture still prevails, in which professionals are held responsible for the mistakes made, thus impacting on AE underreporting and evidencing the fear of professionals reporting their own failures23,24.

In the same way, 50% of the professionals agreed that they had problems in the PS at work. However, they believed that the procedures and systems were adequate to prevent the occurrence of errors (62.5%).

The professionals mostly agreed that the supervisor/boss considered the suggestions for improving the PS, as found in a qualitative study carried out in Goiânia, in which the manager listened and discussed the suggestions offered by the team. It is extremely important that there is a dialogue between the supervisor and the team that is directly in contact with the patients, in order to perceive flaws and weaknesses. Thus, it is possible to intervene in the problem, in order to achieve quality in patient care25-27.

In the same way, it was found in a research carried out in four type II NICUs of four public hospitals in Florianópolis, in which 75% of the professionals also disagreed, in the item “skipping steps” when the pressure increases12. This is considered a positive point for the PS because when the work is done quickly, “skipping steps”, errors are more likely to occur due to the supervisor's existing charge15.

Regarding the direction of the hospital providing a work climate that promotes PS, 66.7% of professionals agreed. Effective leadership plays a fundamental role in promoting learning and a positive culture in the unit, knowing how to listen and coordinate with love makes the performance of teams proactive in favor of PS. Likewise, hospital management plays a fundamental role, as the entire physical, material and human structure depends on it, which are priority requirements for the implementation of a positive safety culture26,28.

The care process was not compromised, according to the professionals' responses (37.5%), when a patient was transferred from one unit to another; however, 36.1% of the professionals agreed that the care was impaired. In a study carried out in a public university hospital in Rio de Janeiro, this dimension was positively evaluated by professionals (36.61%). This point is highlighted by the lack of open communication between teams from different sectors and CE is highlighted as an important strategy to improve the exchange of information26.

As for the actions of the hospital management, the professionals agreed that the management demonstrated that the PS was the main priority (59.7%). However, in another study, it was found that 89.84% of the participants disagreed that PS would be a priority of the direction. The PS must be worked on by everyone in the institution, but it fundamentally depends on the way in which the direction and managers conduct the institutional policy, from the hiring of personnel, professional development policy, choice of products and materials, in short, a multitude of conditions interfere directly on patient safety1.

The professionals reported that it was common to lose information during the shift change (57%), that it was unpleasant to work with professionals from other units (41.6%) and that there were frequent problems in the exchange of information between the units (47.2%). Similar data were found in a research carried out at a university hospital in Rio de Janeiro, which showed a low percentage of positive responses in the three dimensions, 40.71%, 46% and 37.23%, respectively26.

Changing shifts is one of the propitious moments for AEs to occur, since, during this period, information about patient care is lost. It is noticed how communication is still flawed in the services, as well as changes in the service routine are poorly seen and interpreted as problematic. Likewise, it is essential that the shift change occurs in a noise-free place, to avoid misunderstood information28.

A considerable part of the professionals agreed that “the hospital management only seems interested in PS when an AE occurs”. In view of this data, it was found in the literature that 52% of professionals stated that management was only interested when an AE occurred. This can be explained by the fact that PS is still left aside in some institutions, and better attention is only given when an error occurs and puts patients' lives at risk12.

As for the hospital units working well together to provide the best care to patients, professionals agreed (59.7%). Regarding shift changes being problematic for patients, 55.5% of professionals disagreed. However, in another study carried out in Paraná, it was evidenced that 60.3% of professionals considered shift changes to be problematic for patients14, as well as a percentage of negative responses regarding joint work between units in a study of Florianópolis (42%)12.

Communication is a fundamental element in the shift change; correct information must be passed on about the continuity of care, thus reducing the chances of unsafe care18. The perception of a culture unfavorable to PS in intermediate care units is also shown, due to the low percentage of positive responses.

This demonstrates faulty communication between the team. In a survey that evaluated PS in public and private hospitals in Peru, only 35% of professionals gave a positive assessment regarding the degree of open communication, as well as whether professionals thought they could question superiors, when they saw something that could affect the patient negatively24.

In view of this data, it is demonstrated that changes must be made in health services, so that professionals can talk freely about possible care failures, especially those that can negatively affect the PS. They must be free to report mistakes, when made, without fear of punishment. Thus, it is possible to intervene where care is insecure8.

It is noteworthy that in the last 12 months, the majority did not report AE (55.6%). A study carried out in Belo Horizonte showed even greater value in terms of this statement, with 75.4% of professionals not reporting in the last 12 months, with the nurse being the professional who most carried out the notifications22. It is believed that the work overload in the ICU and the inadequate dimensioning of the health teams can influence the lack of time to carry out the notifications correctly. Also, the lack of interest and fear of punishment arising from the notification of errors did not really demonstrate the real problem encountered15.

It is known that errors, when committed, are underreported, which suggests that most errors that do not affect the patient or are noticed before they happen are probably not reported16, which was not demonstrated in this study.

It is also considered that the expansion of knowledge and the training of professionals contribute to the improvement of PS. Some strategies are also used in health services, such as Permanent Health Education (PHE) and training of professionals, contributing to the implementation of a positive safety culture and the recognition and identification of errors29.

The classification of PS, according to the perceptions of health professionals, was “very good” (50%). In a study carried out in 2019 at the NICU, the “regular” grade prevailed (48%). It was found in the literature that nurses, as they constitute the head of nursing, are the professionals who most consider patient safety as “weak”. Thus, it is believed that other categories are unaware of the process and have different perceptions about safety22. It should be noted that each institution has a different culture, from the perspective of professionals, and discussion, feedback and ECS/permanent are ideal for identifying the weaknesses of the service1.

CONCLUSIONS

The study identified that two categories achieved favorable responses regarding the safety culture in the ICU. Aspects of the safety culture were evidenced in need of interventions, considering the desired evaluative levels. The results showed conditions for guidance in relation to the identification of problems in the PS of the institutions surveyed and possible strategies to be carried out.

Health service managers, as well as professionals who are in direct contact with patients, should be directly involved in the search for conditions that favor SP as a priority for the development of safer care.

As a limitation of the study, the sample size was considered, a fact that may be related to the pandemic period, in which professionals find themselves with a high workload in the ICU and little availability to answer the questionnaires. Finally, we suggest the development of new research in the area, with different instruments, so that managers and professionals of health services can develop actions that enable quality care.

REFERENCIAS

1. Minuzzi AP, Salum NC, LocksMOH. Avaliação da cultura de segurança do pacienteemterapiaintensivanaperspectiva da equipe de saúde. Textocontextoenferm. 2016; 25 (2): [ Links ]

2. Brasil. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Assistência segura: uma reflexão teórica aplicada à prática. Brasília: Anvisa; 2017. [ Links ]

3. Nascimento KMB, Carvalho REFL, Girão AA, Freitas GH. Predisposição à eventos adversos em Unidade de Terapia Intensiva. Research, Society and Development. 2020; 9 (8): [ Links ]

4. Gonzalez NS, Garcia DAM, Cerón MEI, Jacinto EAL. Cultura de seguridade del paciente e nun hospital de alta especialidade. Revista de Enfermería Neurológica. 2019; 18 (3): 115-23. [ Links ]

5. Minuzzi AP, Chiodelli SN, OrlandiHLM, Nazareth AL, MATOS. Contribuições da equipe de saúde visando à promoção da segurança do paciente no cuidado intensivo. Esc Anna Nery. 2016; 20 (1): 121-9. [ Links ]

6. Lemos GC, Azevedo C, Bernardes MFVG, Ribeiro HCTC, Menezes AC, Mata LRF. A cultura de segurança do paciente no âmbito da enfermagem: reflexãoteórica. Rev Enferm Cent-Oeste Min. 2018; 8. [ Links ]

7. Lordelo MV, Gama GGG. Segurança do paciente: notificação de incidentes na Unidade de Terapia Intensiva. Rev Enferm Contemp. 2019; 8 (1): 33-40. [ Links ]

8. Mello JF, Barbosa SFF. Cultura de segurança do paciente em unidade de terapia intensiva: perspectiva da equipe de enfermagem. Rev Eletr Enf. 2017; 9. [ Links ]

9. Reis GAX, Oliveira JLC, Ferreira AMD, Vituri DW, Marcon SS, Matsuda LM. Dificuldades para implantar estratégias de segurança do paciente: perspectivas de enfermeiros gestores. Rev GaúchaEnferm. 2019; 40. [ Links ]

10. Soares EA, Carvalho TLC, Santos JLP, Silva SM, Matos JC. Cultura de segurança do paciente e a prática de notificação de eventos adversos. Rev Eletr. Acer da Saúde. 2019; 36. [ Links ]

11. Andrade LEL, Melo LOM, Silva IG, Souza RM, Lima ALB, Freitas MR et al. Adaptação e validação do Hospital Surveyon Patient Safety Culture em versão brasileira eletrônica. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2017; 26 (3): 455-68. [ Links ]

12. Tomazoni A, Rocha PK, Kusahara DM, Souza AIJ, Macedo TR. Avaliação da cultura de segurança do paciente em terapia intensiva neonatal. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2015; 24 (1): 161-9. [ Links ]

13. Bizarra MA, Balbino CM, Silvino ZR. Segurança do paciente - o papel do enfermeiro no gerenciamento de risco focado na UTI. RevistaPró-UniverSUS. 2018; 9 (1): 101-4. [ Links ]

14. Bohrer CD, Marques LGS, Vasconcelos RO, Oliveira JLC, Nicola AL, Kawamoto AM. Comunicação e cultura de segurança do paciente no ambiente hospitalar: visão da equipe multiprofissional. Rev Enferm UFSM. 2016; 6 (1): 50-60. [ Links ]

15. Costa DB, Ramos D, Gabriel CS, Bernardes A. Cultura de segurança do paciente: avaliação pelos profissionais de enfermagem. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2018; 27 (3): [ Links ]

16. Souza CS, Barlem JGT, Rocha LP, Barlem EDL, Silva TL, Neutzling BRS. Cultura de segurança em unidades de terapia intensiva: perspectiva dos profissionais de saúde. Rev Gaúcha Enferm. 2019; 40. [ Links ]

17. Souza VS, Silva DS, Lima LV, Teston EF, Benedetti GMS, Costa MAR et al. Qualidade de vida dos profissionais de enfermagem atuantes em setores críticos. Rev Cuid. 2018; 9 (2): 2177-86. [ Links ]

18. Gomes ATL, Salvador PTCO, Rodrigues CCFM, Silva MF, Ferreira LL, Santos VEP. A segurança do paciente nos caminhos percorridos pela enfermagem brasileira. Rev Bras Enferm. 2017; 70 (1): 146-54. [ Links ]

19. Petersen RS, Marziale MHP. Análise da capacidade no trabalho e estresse entre profissionais de enfermagem com distúrbios osteomusculares. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2017; 38 (3). [ Links ]

20. Mandarini MB, Alvez AM, Sticca MG. Terceirização e impactos para a saúde e trabalho: Uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Revista Psicologia Organizações e Trabalho. 2016; 16 (2): 143-52. [ Links ]

21. Borges F, Bohrer CD, Kawamoto AM, Oliveira JLC, Nicola AL. Grau da cultura de segurança do paciente na percepção da equipe multiprofissional hospitalar. Revista Varia Scientia. 2016; 2 (1): 55-66. [ Links ]

22. Notaro KAM, Corrêa AR, Tomazoni A, Rocha PK, Manzo BF. Cultura de segurança da equipe multiprofissional em Unidades de Terapia Intensiva Neonatal de hospitais públicos. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2019; 27. [ Links ]

23. Costa TD, Salvador PTCO, Rodrigues CCFM, Alves KYA, Tourinho FSV, Santos VEP. Percepção de profissionais de enfermagem acerca de segurança do paciente em unidades de terapia intensiva. Rev GaúchaEnferm. 2016; 37 (3): [ Links ]

24. Arrieta A, SUÁREZ G, Hakim G. Assessment of patient safety culture in private and public hospitals in Peru. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018; 30 (3):186-191. [ Links ]

25. Toso GL, Golle L, Magnago TSBS, Herr GEG, Loro MM, Aozane F et al. Cultura de segurança do paciente em instituições hospitalares na perspectiva da enfermagem. Rev Gaúcha Enferm. 2016; 37 (4). [ Links ]

26. Penha PM, Silva JOC. Avaliação da cultura de segurança do paciente na organização hospitalar de um hospital universitário. Enferm Glob. 2017; 16 (1): 309-52. [ Links ]

27. Beccaria LM, Meneguesso B, Barbosa TP, Aparecida RPM. Interferências na passagem de plantão de enfermagem em unidade de terapia intensiva. Cuid Art Enferm. 2017; 11 (1): 86-92. [ Links ]

28. Tobias GC, Bezerra AL, Moreira IA, Paranaguá TTB, Silva AEBC. Conhecimento dos enfermeiros sobre a cultura de segurança do paciente em hospital universitário. Rev enferm UFPE online. 2016; 10 (3): 1071-9. [ Links ]

29. Wegner W, Silva SC, Kantorski KJC, Predebon CM, Sanches MO, Pedro ENR. Educação para cultura da segurança do paciente: Implicações para a formação profissional. Esc Anna Nery. 2016; 20 (3). [ Links ]

Received: August 02, 2021; Accepted: January 03, 2022

texto em

texto em