Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Enfermería Global

versão On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.21 no.67 Murcia Jul. 2022 Epub 19-Set-2022

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.490561

Originals

Exploring the experience of community health workers in COVID-19 pandemic response in Indonesia: a qualitative study

1Departement of Community Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia. Indonesia

Background:

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a communicable disease that has infected millions of people in many countries, including Indonesia. Community health workers (CHWs) play a pivotal role in supporting primary health center programs, including in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods:

We conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews with thirteen CHWs in Makassar City, Indonesia. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results:

Six themes emerged from the interviews: (1) self-motivation; (2) valuable benefits; (3) noble duties; (4) perceived challenges; (5) meaningful support; and (6) way forward.

Conclusions:

Despite the challenges experienced by the participants, the involvement of CHWs is crucial to ensure that the community receives correct information and complies with health protocols to break the chain of COVID-19 transmission. The participants undertake the task with strong commitment and the feel of honor as they are trusted by the government and the community. The partnership between health service staffs and CHWs should be strengthened by providing sufficient support so COVID-19 cases in the community can be contained.

Keywords: Community health workers; COVID-19; Indonesia

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, which has infected millions of people worldwide. Infected persons will experience symptoms ranging from mild respiratory disorders, such as flu, to severe respiratory disorders, such as lung infections1,2. COVID-19 is transmitted rapidly to humans and can cause severe diseases particularly in vulnerable populations, such as the elderly with comorbidities3,4.

By July 2021, the number of confirmed cases worldwide has reached 197,943,446, of which 4,222,934 died5).Indonesia has continued to experience an increase in confirmed cases, and the accumulated number of cases reached 3,409,658; of which, 94,119 (3%) died, and 2,770,092 (81%) were cured6. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries have utilized a combination of control strategies to contain the spread of the virus while protecting the most vulnerable groups from the infection, including the elderly and individuals with comorbidities. Most countries adopt a spread control strategy through a health promotion approach7. Health promotion is a key intervention in disease prevention and a way for every individual or community to adopt optimal health behavior8. Information about COVID-19 needs to be disseminated to the public so they will know how to protect themselves from infection and be aware of the importance of social responsibility and correct preventive behavior9. The other prevention and control measures in suppressing the spread of the virus include diligently washing hands, maintaining social distance, increasing contact tracing, isolation or self-quarantine, and postponing large-scale public gatherings10).

Indonesian community health workers (CHWs), known askaders, are community members who are willing and able to carry out health promotion activities11. CHWs are critical to liaison between the community and primary health centers. CHWs actively support the health centers to limit the spread of disease outbreaks by early detection of cases and rapid response. They control outbreaks by involving and educating the public to implement preventive measures12,13.

Many countries have developed strategies to control this pandemic by involving CHWs as key populations in the community. For example, in the US, when COVID-19 hit the New York City, the disease became an initial and worrying threat to public health; the government developed a strategy by empowering CHWs to overcome misinformation, fear, and stigma on COVID-19 circulating in the community by providing information about how the virus is transmitted, precautions people can take to protect themselves and their families, and ways to gain support and access to health services14,15. Other countries such as Bangladesh, India, and Thailand also involved CHWs in the pandemic response through education, including promotion of adaptation of new habits, assisting in surveillance, contact tracing and quarantine efforts, and maintaining essential health services16).

From our preliminary study, we found that the District Health Office has proactively carried out health promotion of COVID-19 prevention and trained CHWs to actively participate in breaking the chain of COVID-19 transmission in the community. Understanding the CHWs' point of view about their participation in the program is important given that working with the community in pandemic situation is considered a risky task. Limited information is known about the experience of CHWs in efforts to contain COVID-19, particularly in the Indonesian context. Hence, we conducted this study to explore the experience of CHWs in the COVID-19 pandemic response in the country. We expect that the findings will be useful to inform stakeholders in enhancing the strategy of community empowerment to handle an infectious disease outbreak in the community.

METHODS

Study design

We used a qualitative design with a descriptive approach to elucidate the similarity of the meaning of participants' experience17,18. This approach helped us to understand the meaning of the live experience of CHWs by in-depth exploration of what they have undergone and felt in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants

This study involved thirteen CHWs who were selected using purposive sampling. Primary health center staffs were screened for participants who meet the inclusion criteria: active CHWs who carried out activities related to COVID-19 response and were willing to participate in this study.

Data collection

We conducted the study between February and March 2021. Data were collected through personal semi-structured interviews following strict health protocol. When face-to-face interviews were not possible, we conducted video or phone calls. We developed an interview guide based on the research objectives. Prior to the interviews, we explained the procedure and purpose of the study to the participants. Informed consent was obtained upon the agreement of the participants to be involved in the study.

Data analysis

The interview was recorded and transcribed. The transcript was then translated into English and then back into Bahasa Indonesia to ensure the similarity of meaning. Colaizzi method was used to analyze data19. The analysis was conducted by reading the transcript several times to gain an understanding of the meaning conveyed, identify significant phrases, formulate and validate the meaning through discussion within the research team to reach agreement, identify and organize themes into groups and categories, and develop descriptions about the theme.

Trustworthiness and credibility

Several strategies were used to ensure the trust and credibility of the research results. We examined the credibility of the data by member checking, where we re-confirmed the findings of the research results to the participants to be checked for correctness and validated the results to other participants who were not involved in this study to obtain accurate information. We also engaged in data interpretation and triangulating sources by involving the person in charge of the health promotion program at the primary health center responsible for CHW activities.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the research ethics committee, Faculty of Nursing, University of Indonesia (No: SK-21/UN2.F12.D1.2.1/ETIK 2021). We guaranteed the confidentiality of the participants by using a code in each interview transcript (e.g., P1, P2 etc.). All audio recordings and transcripts are stored on a password-protected electronic file.

RESULTS

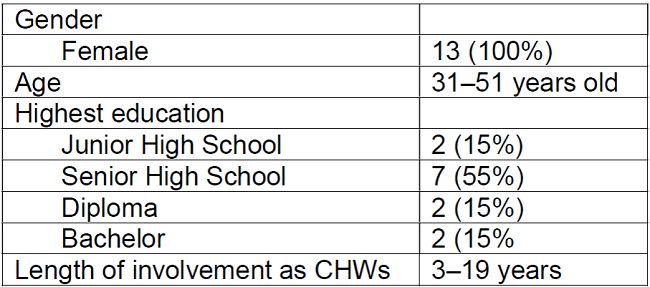

Thirteen CHWs participated in the study. The characteristics of the participants are shown inTable 1.

Six themes emerged from the study: (1) self-motivation, (2) valuable benefits, (3) noble duties, (4) perceived challenges, (5) meaningful support, and (6) way forward.

Self-motivation

The reason why CHWs became involved in COVID-19 response is their strong motivation. CHWs are willing to be involved in COVID-19 prevention. They also have a strong commitment to carry out their role as CHWs and to be part of the primary health center. A participant said:

“The reason I became a CHW was because I felt called to convey health information related to COVID-19 and wanted to be part of the primary health center as an extension of the hand of the center in the community.” (P3)

Another participant said:

“As a kader, I am responsible for helping the government to convey correct information about COVID-19 to the public.” (P8)

Valuable benefits

The lesson learned by CHWs while carrying out efforts to deal with COVID-19 is that they acquire valuable benefits from every activity they conducted. This theme was obtained from the participants' expression during the pandemic, that is, they increased their vigilance in doing activities and increased their awareness. One of the participants said:

“Our fellow citizens must understand this situation and take care of each other.” (P9)

The participants also have increased awareness on how to maintain health, as shown when a participant said:

“This pandemic teaches us to live healthy and to not ignore health protocols.” (P13)

Another benefit received by CHWs is the establishment of social relations with the community. The participants get to know the community better through health programs implemented, and one of them said:

“During this pandemic we always remind the residents to maintain health protocols and greet each other when meeting on the street.” (P5)

The knowledge of CHWs has also increased during this pandemic because they often get many opportunities to receive information from the primary care center. This theme was expressed by a participant who said:

“Pandemic provides an opportunity to know the dangers of COVID-19.” (P3)

Noble duties

The CHWs conveyed that undertaking their task in pandemic situation is a noble duty. They feel proud because they have been trusted and selected by the community to conduct the special task. They have to do particular task related to COVID-19 in addition to their routine jobs as CHWs. They felt that it is special as expressed by a participant who said:

“During the pandemic we as kaders feel honored, we are trusted by the community… We actively educate the public about the dangers of COVID-19 through various media, including through mosque loudspeakers, mobile counseling and distributing pamphlets” (P6)

In addition to specific tasks performed, the participants continue to undertake routine tasks, namely, helping the primary health center to provide health services. This finding was conveyed by a participant who said:

“During this pandemic, we as kaders also continue to make home visits to provide health services to the elderly, children under-five and teenagers.” (P9)

CHWs also provide vitamin A to toddlers:

“During the pandemic, the community clinic (Posyandu) was closed so that we as kaders went out in the community targeting toddlers to be given vitamin A.” (P12)

Perceived challenges

The challenges faced by CHWs in undertaking their duties during the COVID-19 pandemic are brought about by the following” community's negative attitude toward the pandemic, decreasing level of community compliance in implementing health protocols, inadequate facilities and infrastructure in carrying out their duties, and lack of time management.

The negative attitudes of the community are evident when CHWs conduct health promotion on COVID-19 prevention. These attitudes include boredom experienced by the community because they have to stay at home, nagging or being indifferent when they are told, not believing in COVID-19, not being aware of the dangers of the pandemic, lack of understanding about the disease, doubtful because they believe COVID-19 is an artificial disease, getting bullied during counselling, and believing on hoax news about COVID-19. This was expressed by several participants who said:

“People are less obedient and start to ignore wearing masks and assume COVID-19 does not exist” (P1)

“Many people do not believe in this COVID-19 pandemic, there are still people who are not aware and are still crowding, as well as the understanding of some people who consider COVID-19 as a form of political conspiracy” (P3)

Meaningful support

In undertaking their tasks, the participants receive support from the primary health centers. These supports include information regarding prevention efforts, financial support, facilities in prevention efforts, motivational support, and social support from the community. This can be seen when several participants said that the primary health centers actively conducted training and health promotion related to COVID-19 through a CHWs refresher program. After the training, they received some money for transportation. In addition, CHWs were equipped with masks and hand sanitizers in supporting the implementation of activities in the community. (P1, P4, P7, P8)

Way forward

Participants believe that several factors could contribute to strengthening their roles as CHWs during the pandemic. These factors include improving financial assistance and support for personal protective equipment, continuing the development of knowledge about COVID-19, improving the performance of primary health centers and the Government, supporting each other in the application of health protocols, and increasing the community understanding about the importance of vaccination. CHWs also wish to be given special incentives for their effort to handle the COVID-19 pandemic. This was expressed by several participants who said that in addition to the monthly incentives provided by the primary health center, they also want additional special incentives (P1, P6, P11)

In addition to special incentives, CHWs want updated information regarding the development of COVID-19 cases. This was expressed by a participant who said:

“Our hope as kaders is the renewal of knowledge or more updated information provided for us.” (P7)

Furthermore, CHWs also hope that the performance of the primary health center and the government can be improved and that they should support each other in the implementation of health protocols. They also expect that the community understands the importance of vaccination. This was conveyed by a participant who said:

“We as Kaders want the government to be more assertive in dealing with the crisis, the active participation of the community to be more obedient in implementing health protocols, and we want the public to be vaccinated.” (P9)

DISCUSSION

We conducted this study to understand the experience of CHWs in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the reasons why CHWs are involved in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic is due to their strong self-motivation. Motivation is a central concept in behavior change and an inner desire that drives a person to work with a high level of commitment20. The motivation described in Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is divided into extrinsic and intrinsic factors. Extrinsic factors are the desire of someone who works because of external contingencies, such as wages or bonuses obtained for the performance done. Intrinsic factors are motivations that arise within themselves due to the intention to achieve certain goals21. The present study reveals an intrinsic factor, that is, CHWs have willingness or motivation to contribute and be involved in handling and controlling the COVID-19 pandemic. This finding is in line with the meta-synthesis study conducted by Mohajer & Singh (2018), who identified factors, including call to serve, assist, and empower the community, which enable CHWs to bring about behavior change22. Another study stated that the existence of a high sense of empathy and concern is the reason why CHWs build relationships with stigmatized people in the context of AIDS intervention23).

In the implementation process, our study shows that the participants received many benefits in carrying out their duties in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. A qualitative study was conducted by Carroll et al. (2020) on strategies to cope with change during the pandemic; the results showed that some respondents reported the coping strategies they used to manage stress and lifestyle changes due to restrictions due to COVID-19, and they were more aware and wiser in facing the pandemic and focused on the positive aspects that can be done24. In addition, another study conducted by Balkhi et al., (2020) stated that more than three quarters of respondents admitted a change in their behavior to maintain health and ensure safety from COVID-19 transmission25. The health behavior/practices carried out by respondents include reducing physical contact as much as possible (86.5%), canceling activity plans (84.5%), and more often washing of hands (87%)25.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, CHWs are mandated with two tasks, namely, special tasks and routine tasks. The special task is the task of handling the pandemic, while the routine task comprises any activities to ensure that essential health programs are delivered to the community. CHWs actively conduct health education and share information about the dangers of COVID-19 to the community in their respective areas of residence. According to Ervin (2002), health promotion is a health intervention carried out directly to the community to change lifestyle and environmental behavior toward better health26. A qualitative study conducted by Sawee et al. (2021) showed that during the pandemic, CHWs in Vietnam were actively responsible for conveying information about COVID-19 to the public and advising them on how to protect themselves from transmission of the virus27.

In addition, our study indicates that the primary care centers ensure the continuous provision of essential health services even with some modifications, one of which is through the approach of CHW empowerment. Our study corroborates with a previous work that stated that the role of CHWs during the pandemic is not only to take infection prevention and control measures but also to help maintaining primary health services, such as vaccination and integrated case management of children with malaria, pneumonia, and diarrhea28.

In implementing the COVID-19 response initiatives, CHWs encounter many challenges. The challenge is in the form of the community's attitudes that tend to be negative. For example, some CHWs reveal that many people are indifferent when educated, do not believe in COVID-19, and think it is only an artificial disease; moreover, many hoax news circulate in the community, and CHWs have been bullied. This is in line with the findings of the Center for Indonesia's Strategic Development Initiatives (CISDI), which indicates that the common challenges in changing people's behavior include the following: health protocols that are only considered a formality so that they are applied only during inspections or raids; people continue to ignore health protocols despite knowing the dangers of COVID-19 because they are urged by other interests, such as having to sell, work, etc.; and people are increasingly ignoring the implementation of health protocols because there is no law enforcement for violators, especially in public places, such as markets29.

Despite these challenges, CHWs also receive various supports, including information support regarding prevention and COVID-19 efforts, financial support, supporting facilities in efforts to prevent COVID-19, motivational support from primary health centers, and social support from the community. This finding is reinforced by the study of Rosalia (2017), who reported the effect of refreshing CHWs' training on knowledge and skills in the implementation of health services30. Another study showed that the provision of basic health information could significantly increase the knowledge of CHWs31).In addition, a qualitative study identified several sources of CHWs motivation, one of which is financial and material support, including service fees and money for transportation32.

During this pandemic, CHWs have a lot of expectations to facilitate activities in the community. Greenspan et al. (2013) stated that moral support and material support are the main sources that motivate CHWs in carrying out their roles in the community32. Another study stated that internal factors that affect the performance of CHWs include motivation, recognition from the government, and award given by the health office to CHWs in carrying out their duties and responsibilities33).

CONCLUSION

CHWs play an important role in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The participants have shown their dedication in assisting the government and the community in handling COVID-19. Despite the challenges they encounter, CHWs have carried out various health promotion activities with a sense of responsibility. Comprehensive support must be provided to maintain the performance and well-being of CHWs. The findings of this study are expected to provide a rich description surrounding CHWs' involvement in the COVID-19 pandemic disaster so related stakeholders can increase their understanding when engaging with CHWs in similar programs and contexts.

REFERENCES

1. Zhai P, Ding Y, Wu X, Long J, Zhong Y, Li Y. The epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55. [ Links ]

2. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727-33. [ Links ]

3. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet [Internet]. 2020;395(10223):507-13. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 [ Links ]

4. Munster VJ, Koopmans M, van Doremalen N, van Riel D, de Wit E. A novel coronavirus emerging in China - Key questions for impact assessment. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):692-4. [ Links ]

5. WHO. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard 2020 [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 29]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/ [ Links ]

6. Satgas Penanganan COVID-19. Map of the distribution of Covid-19 in Indonesia [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Mar 29]. Available from: https://covid19.go.id/peta-sebaran [ Links ]

7. Bedford J, Enria D, Giesecke J, Heymann DL, Ihekweazu C, Kobinger G, et al. COVID-19: towards controlling of a pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(April):1315. [ Links ]

8. Salama BMM. The importance of health promotion in the prevention of COVID-19. Ann Clin Anal Med. 2020;11(suppl 3). [ Links ]

9. Ward DJ. The role of education in the prevention and control of infection: A review of the literature. Nurse Educ Today [Internet]. 2011;31(1):9-17. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.03.007 [ Links ]

10. Deng S-Q, Peng H-J. Characteristics of and Public Health Responses to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak in China. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):575. [ Links ]

11. Oendari A, Rohde J. Indonesia's Community Health Workers (Kaders) [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2021 Jul 31]. Available from: https://chwcentral.org/indonesias-community-health-workers-kaders/ [ Links ]

12. Perry HB, Dhillon RS, Liu A, Chitnis K, Panjabi R, Palazuelos D, et al. Community health worker programmes after the 2013-2016 Ebola outbreak. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(7):551-3. [ Links ]

13. Miao Q, Schwarz S, Schwarz G. Responding to COVID-19: Community volunteerism and coproduction in China. World Dev [Internet]. 2020;137:105128. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105128 [ Links ]

14. Peretz PJ, Islam N, Matiz LA. Community Health Workers and Covid-19 - Addressing Social Determinants of Health in Times of Crisis and Beyond. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2020;31(1):1969-73. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/ [ Links ]

15. Heath S. Community Health Workers Play Key Role in COVID-19 Response [Internet]. Patient Care Access News. 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 23]. Available from: https://patientengagementhit.com/news/community-health-workers-play-key-role-in-covid-19-response [ Links ]

16. Bezbaruah S, Wallace P, Zakoji M, Padmini Perera WS, Kato M. Roles of community health workers in advancing health security and resilient health systems: emerging lessons from the COVID-19 response in the South-East Asia Region. WHO South-East Asia J Public Heal. 2021;10(3):41. [ Links ]

17. Streubert HJ, Carpenter DR. Qualitative Research In Nursing: Advancing The Humanistic Imperative. Fifth. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. [ Links ]

18. Cresswel J. Research design. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 2013. [ Links ]

19. Phillips-Pula L, Strunk J, Pickler RH. Understanding phenomenological approaches to data analysis. Vol. 25, Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2011. p. 67-71. [ Links ]

20. Sands L. What are motivation theories? [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.breathehr.com/en-gb/blog/topic/employee-engagement/what-are-motivation-theories [ Links ]

21. Flannery M. Self-determination theory: Intrinsic motivation and behavioral change. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017;44(2):155-6. [ Links ]

22. Mohajer N, Singh D. Factors enabling community health workers and volunteers to overcome socio-cultural barriers to behaviour change: Meta-synthesis using the concept of social capital. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1):1-9. [ Links ]

23. Maes K. "Volunteers Are Not Paid Because They Are Priceless": Community Health Worker Capacities and Values in an AIDS Treatment Intervention in Urban Ethiopia. Med Anthropol Q. 2015;29(1):97-115. [ Links ]

24. Carroll N, Sadowski A, Laila A, Hruska V, Nixon M, Ma DWL, et al. The impact of covid-19 on health behavior, stress, financial and food security among middle to high income canadian families with young children. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):1-14. [ Links ]

25. Balkhi F, Nasir A, Zehra A, Riaz R. Psychological and Behavioral Response to the Coronavirus ( COVID-19 ) Pandemic. Cureus Publ Beyond Open Acces. 2020;12(5). [ Links ]

26. Ervin NE. Advanced Community Health Nursing Practice: Population-focused Care. Prentice Hall, editor. Universitas Michigan: Prentice Hall; 2002. [ Links ]

27. Sawee K, Naklang S, Behara M, Sangpaew K. The Roles Of Village Public Health Volunteer ( Vphv ) Conducting The Prevention And Reduction Of The Covid-19 Pandemic In Pattani. Psychol Educ. 2021;58:1997-2003. [ Links ]

28. Ballard M, Bancroft E, Nesbit J, Johnson A, Holeman I, Foth J, et al. Prioritising the role of community health workers in the COVID-19 response. BMJ Glob Heal. 2020;5(6):1-7. [ Links ]

29. Audwina AH. Improving Public Health Protocol Compliance Through Behavior Change Communication [Internet]. Center for Indonesia Strategic Development Initiatives. 2021 [cited 2021 Aug 4]. Available from: https://cisdi.org/id/gva_event/meningkatkan-kepatuhan-protokol-kesehatan-masyarakat-melalui-komunikasi-perubahan-perilaku/ [ Links ]

30. Rosalia V. The Effect of Refreshing Posyandu Cadres on Knowledge and Skills of Posyandu Cadres Regarding the 5 (five) Desk System [Internet]. [Indonesia]: Poltekkes Kemenkes Bandung; 2017. Available from: http://repository.poltekkesbdg.info/items/show/836 [ Links ]

31. Chahyanto BA, Pandiangan D, Aritonang ES, Laruska M. Providing basic information on Posyandu through cadre refresher activities in increasing cadre knowledge at the Sambas Port Health Center, Sibolga City. AcTion Aceh Nutr J. 2019;4(1):7. [ Links ]

32. Greenspan JA, McMahon SA, Chebet JJ, Mpunga M, Urassa DP, Winch PJ. Sources of community health worker motivation: A qualitative study in Morogoro Region, Tanzania. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11(1). [ Links ]

33. Andodi, Ainy A, Misnaniarti. Internal and External Factors of Motivation of Health Cadres in Implementing Alert Village in District of Ogan Ilir in 2011 Penda. J Imu Kesehat Masy. 2014;5:122-6. [ Links ]

Received: August 30, 2021; Accepted: January 14, 2022

texto em

texto em