Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Enfermería Global

versão On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.22 no.72 Murcia Out. 2023 Epub 04-Dez-2023

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.551621

Reviews

Interventions for Prostate-Specific Antigen Testing: a rapid literature review

1Faculty of Nursing. Benemérita Autonomous University of Puebla, México

Objective:

To identify the best available evidence related to interventions for the acceptance of the prostate-specific antigen test.

Methodology:

Rapid literature review following the steps established by Tapia-Benavente, which are: 1.- research question, for which the PICO structure limited to the definition of the problem, intervention, and result was used; 2.- bibliography search in recognized databases; 3.- study selection and data extraction; 4.- bias risk assessment, for which the CONSORT group clinical trial verification guidelines were used; and 5.- preparation of a summary and conclusion of the evidence found.

Results:

The rapid literature search yielded a total of 51 publications from three databases, PubMed (27), EBSCO (13), and SCOPUS (11); 11 of which met the inclusion criteria. One hundred percent of the studies indicated a significant difference between the experimental and control groups (p < .05). The most frequently used strategies included home visits, conferences, group discussions, brainstorming, question-and-answer dynamics with slides, as well as the use of educational brochures, and were carried out in a period of one day and up to six months.

Conclusions:

There is an evident knowledge gap in the development and implementation of strategies for Prostate Cancer prevention behavior directed to indigenous men, as well as a lack of nursing intervention models focused on this disease.

Keywords: Randomized Clinical Trial; prostate cancer; Prevention; Intervention

INTRODUCTION

According to the World Health Organization, 1,414,259 people were diagnosed with prostate cancer (PCa) in 2020 (1), making it the leading cause of death among men over 50 years of age worldwide (2). This situation is no different in Mexico, since it was considered the deadliest disease in 2022, with 9.8 deaths per 100 thousand men and an approximate catastrophic expenditure of 2,218 dollars (4).

In this sense, diagnostic methods, such as digital rectal examination (DRE) and Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) testing, are important for the early detection of PCa, as well as for the development of health interventions with the purpose of not only contributing to the knowledge related to PCa, but also to the acceptance and application of these detection tests.

Studies focused on the evaluation of health interventions mention that the application of educational intervention programs with public health or pedagogical models are usually effective (5,6,7). However, it has also been found that the main obstacles are lack of cultural adaptation and the long duration of the interventions, which does not align with the availability of the target population. It has also been recommended that diagnostic tests should be offered during the interventions, and the tests should be quick and with flexible hours (8,9).

Considering the above, it is necessary to identify the best available evidence related to interventions for the acceptance of the prostate-specific antigen test, in addition to the fact that, thus far, there is no literature review to serve as a guide for adequate and effective strategies for health professionals to better approach this topic. This leads to the following research question: What is the best available evidence related to interventions for the acceptance of the prostate-specific antigen test?

METHODOLOGY

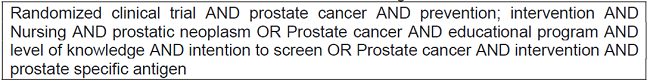

A rapid literature review was conducted following the steps established by Tapia-Benavente et al.,(10), which are: 1.- research question, for which the PICO structure limited to the definition of the problem, the intervention, and the result was used; 2.- a search of bibliography from 2016 to 2022 in recognized databases such as EBSCO, SCOPUS, and PubMed using a search string with Boolean operators (AND, OR) and health science descriptors (HSDe) (Table 1). 3.- study selection and data extraction, using the following inclusion criteria: full-text, open-access research papers in English or Spanish with results limited to the acceptance or non-acceptance of the prostate-specific antigen test, and the following exclusion criteria: duplicate articles, theses, dissertations, and studies that did not fit the objective of the present study; it should be noted that the reference manager Mendeley was used to store and organize the publications found; 4.- bias risk assessment using the CONSORT group clinical trial verification guidelines (11), which consist of 22 questions divided into four sections: a) title and abstract, b) introduction, c) methods, and d) results and discussion, as well as a flow diagram that can be used by authors, editors, reviewers, and readers to improve the quality of reporting of randomized clinical trials; and 5.- preparation of a summary and conclusion of the evidence found.

RESULTS

Search results

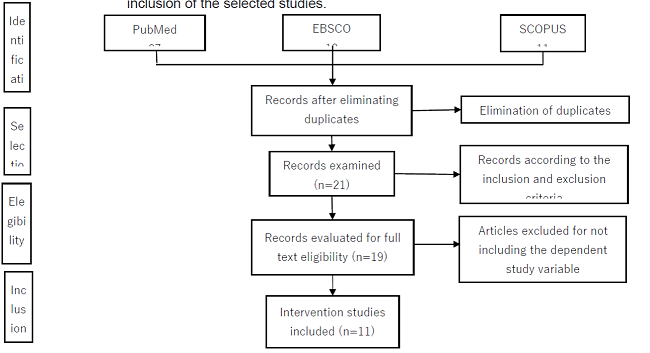

The rapid literature search yielded a total of 51 publications from three databases, PubMed (27), EBSCO (13), and SCOPUS (11), no older than ten years after conducting the study and after the elimination of duplicates. In the title selection by relevance (studies of interventions for PCa in any location), 30 studies were excluded, which resulted in a total of 21 full texts evaluated. After applying the quality criteria, eight studies were excluded for not specifying the intervention design or clarifying the type of screening performed, and they also did not include the dependent study variable. Finally, a total of 11 studies were used for the literature review (Figure 1).

Source: Created by the authors, based on the PRISMA Statement

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram (12) for a systematic review of the literature and the inclusion of the selected studies.

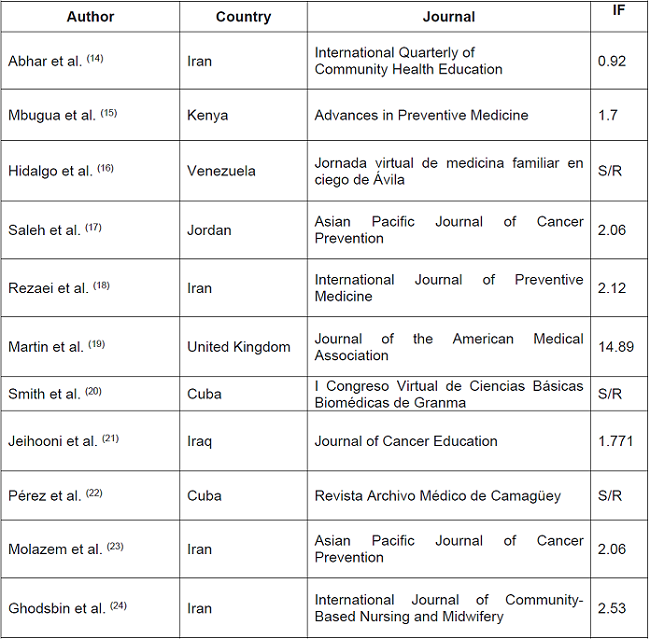

Characteristics of the studies

The 11 studies used were conducted in countries from Asia (Iraq, Iran, and Jordan), Africa (Kenya), Europe (United Kingdom), and America (Cuba and Venezuela), which was where the incident rates of PCa were the highest (111.6 and 97.2 cases per 100,000 men, respectively) (13), while the lowest occurred in the Asian countries (4.5 to 10.5 cases per 100,000 men). The studies were published in international journals with a high impact factor such as Journal of the American Medical Association, Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, International Journal of Community-Based Nursing and Midwifery, and International Journal of Preventive Medicine (Table 1).

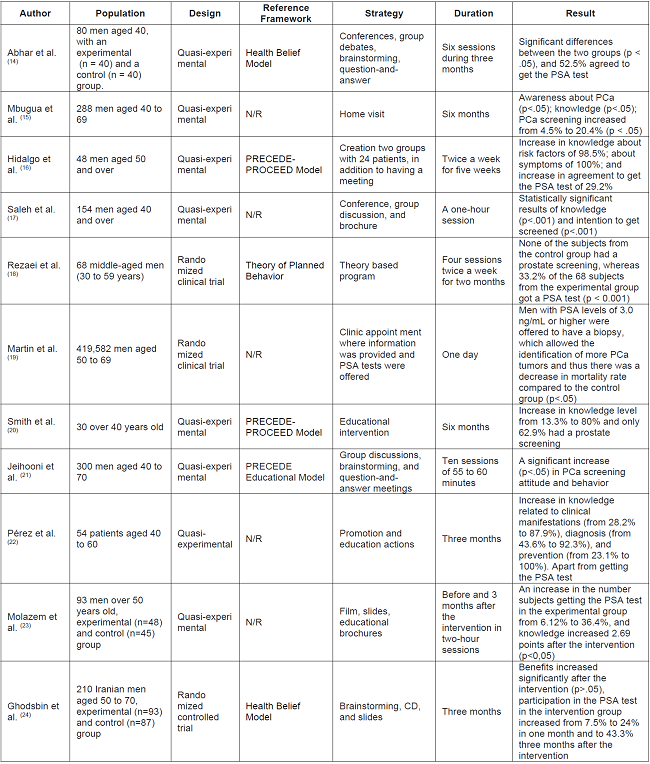

Based on the characteristics of the selected studies that focus on interventions for the acceptance of the prostate-specific antigen test, there was increased focus on non-modifiable factors such as age, family history, and race or ethnic group. Therefore, the aim of prevention efforts was for men to get the PSA test from the age of 40 with the purpose of decreasing the mortality rate in the target population. This emphasizes the importance of the interventions, which generated significant differences between experimental and control groups (p< .05) and resulted in more than 50% of subjects agreeing to take the PSA test, which was related to an increase in the knowledge (p<.05) about risk factors, signs, and symptoms. This was achieved through strategies such as home visits, conferences, group debates, brainstorming, question-and-answer dynamics with slides, and the use of educational brochures, which were carried out in a period of one day and up to six months. Of the studies selected, eight corresponded to a quasi-experimental design (14,15,16,17,20,21,22,23) and three to a randomized clinical trial (18,19,24), and were based on different reference frameworks, with the PRECEDE-PROCEED Model being the most frequently used in these studies, followed by the Health Belief Model (14,24) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (18). It should be noted that five studies did not mention any reference framework and did not report any PCa information at the beginning of the intervention (15,17,19,22,23) (Table 2).

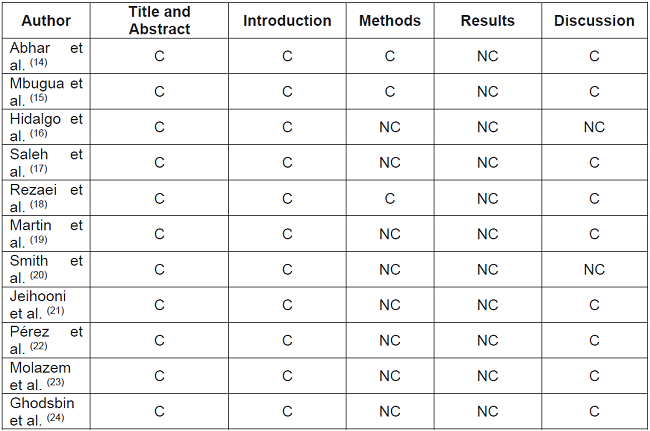

The qualitative assessment of the selected studies based on the CONSORT group clinical trial verification guidelines showed that most of the studies complied with the requirements for the abstract and introduction, based on the scientific and epidemiological background of the disease and the objectives and rationale of the project. However, in the case of the methods, Hidalgo et al., (16) and Martin et al., (19) did not include a description of the design, details to allow replication, an explanation of any interim analyses and stopping guidelines, and who generated the random allocation sequence of the participants in the interventions, including a description of the similarity of interventions and changes to the methods after trial commencement, as well as methods for additional analyses. In the case of the results, the studies by Smith et al. (20); Ghodsbin et al. (24); Abhar et al. (14); Mbugua et al. (15); Saleh et al. (17); Jeihooni et al. (21), and Molazem et al. (23) did not include the dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up. The studies by Martin et al. (19) and Hidalgo et al. (6) did not specify the demographic and clinical characteristics of each group (intervention and control), and the studies by Abhar et al. (15) and Martin et al. (16) did not include subgroup analyses, distinguishing pre-specified from exploratory.

In the case of the discussion, the studies by Molazem et al. (23) and Smith et al. (20) did not clarify the limitations, sources of potential bias, and possible generalization (external validity and applicability) of the trial findings. Finally, the studies by Smith et al. (20); Hidalgo et al. (16), and Jeihooni et al. (21) did not include the data of where the full trial protocol can be accessed (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The present study aimed to identify the best available evidence related to interventions for the acceptance of the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test, and the results showed that most studies used a quasi-experimental design without a control group (15,16,17,20,22). The studies were based on different reference frameworks, with the most frequently used being the PRECEDE-PROCEED methodological approach (16,20,21) followed by the Health Belief Model (14,24). Five studies did not use any reference framework and did not mention who generated the random allocation sequence of the participants in the groups (15,17,19,22,23), which does not allow an interpretation in terms of the selection and implementation of the interventions in order to improve health-promoting behaviors.

The above also complicates the replication of this type of studies. However, this has not been a limitation for the development of strategies by health professionals or for the creation of intervention models for the acceptance of the PSA test.

In the case of the characteristics of the male subjects, the results agree with existing data showing that men are the least concerned and have a low level of preventive health behaviors (8), which may lead to an increase in cases of PCa and other diseases that, if not detected in time, may cause serious complications in the quality of life of individuals. Given this situation, one may also question the lack of focus on indigenous men, which would imply, rather than an ideological challenge, an opportunity to promote responsible preventive health behaviors without invading their beliefs and customs.

The barriers that prevent men from deciding to have a prostate screening exam were observed as a concept involving beliefs that interfere with knowledge and preventive behavior related to PCa. This includes variables such as age, religion, education, stigmas of being a macho man, the quality of the information, and the care given by the health staff (14,24), and can contribute to a decrease in preventive behavior.

The influence of non-modifiable factors on behavioral change is highly important, since it was found in all 11 studies, and thus prevention efforts aim to encourage men to get the PSA test from the age of 40 in order to have an early detection and avoid possible complications.

It was also found that families may or may not favor the responsibility of PCa prevention behaviors (15,23), which should be considered in future interventions. In the case of acceptance of the PSA test, all research studies showed that more than 50% of men got tested after the intervention, which was related to increased knowledge about the risk factors and symptomatology of the disease (p<.05) (15,16,17,20,22,23) through strategies such as home visits (15,23), conferences (14,17), and group debates (14,17,21).

It is important to mention that there are noTable differences in the approach to this health problem in each country, since the health education provided by health workers during health promotion on the awareness, knowledge, perception, and acceptance of prostate screening is mostly carried out outside of the cultural context, with unsuiTable language, and at inflexible hours (17,18). This situation has, on the one hand, resulted in poor knowledge about PCa in the male population and, on the other hand, set back the acceptance and application of prostate screenings, increasing thus the number of clinical cases with delayed treatment.

Finally, these results indicate that knowledge should be provided and improved in order to counteract existing stigmas that prevent the application of PCa detection tests. This can be done through the creation of intervention models that promote a culture of responsible prevention and that will help to reduce prevalence rates related to PCa.

CONCLUSIONS

The rapid literature review carried out in the present study showed the knowledge gaps that exist in the development and implementation of strategies that address PCa prevention behavior in indigenous men, as well as the lack of nursing intervention models focused on this disease. This situation shows the need to guide the practice of promoting, managing, and addressing the professional care of these groups, taking into account barriers that discourage men from getting a prostate screening, knowledge related to PCa, and family support.

REFERENCIAS

1. Organización Mundial de la Salud. OMS. [Internet]. Cáncer. [Obtenido: el 8 de noviembre de 2022]. Disponible en: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer [ Links ]

2. Organización Mundial de la Salud. OMS. [Internet]. Datos y cifras, Cáncer. [Obtenido: el 17 de octubre 2022]. Disponible en: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer [ Links ]

3. Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública. (INSP). [Internet]. Mortalidad por cáncer de próstata en México a lo largo de tres décadas. [obtenido: el 27 de octubre de 2022]. Disponible en: https://www.insp.mx/avisos/4189-cancerprostatamx.html [ Links ]

4. Rascón Pacheco, R. A., González León, M., Arroyave-Loaiza, M. G., & Borja-Aburto, V. H. Incidencia, mortalidad y costos de la atención por cáncer de pulmón en el Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social. Salud Pública de México. [Internet]. 2019 [Obtenido: el 19 de noviembre del 2022]. 61 (3), 257-264. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.21149/9808 [ Links ]

5. Miller David B., Tyrone Hamler, C. & Weidi Q. Prostate cancer screening in Black men: Screening intention, knowledge, attitudes, and reasons for participation. Social Work in Health Care. [Internet]. 2020 [obtenido: el 29 de octubre de 2022]; 59, 543-556. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2020.1808149 [ Links ]

6. Calpa A., Santacruz G., Álvarez M., Zambrano C., Hernández E., Matabanchoy S. Promoción de estilos de vida saludables: estrategias y escenarios. Revista Hacia Promoción de la Salud. [Internet]. 2019 [obtenido: el 16 de diciembre de 2022]; 24 (2): 139-155. Disponible en: https://revistasojs.ucaldas.edu.co/index.php/hacialapromociondelasalud/article/view/2911 [ Links ]

7. Menor R, Aguilar C, Mur V, Santana M. Efectividad de las intervenciones educativas para la atención de la salud. Revisión sistemática. Medisur. [Internet] 2017 [Obtenido: el 16 de diciembre de 2022]; 15(1): 71-84. Disponible en: http://www.medisur.sld.cu/index.php/medisur/article/view/3424 [ Links ]

8. Cruz Bertan, F., & Kern de Castro E. Conductas de autocuidado y salud del hombre: el cáncer de próstata como ejemplo. Summa Psicológica. [Internet]. 2018 [obtenido: el 28 de octubre de 2022]; Disponible en https://summapsicologica.cl/index.php/summa/article/view/345/355 [ Links ]

9. Durães Oliveira, P. S., Vinicius Cardoso de Miranda S., Andrade Barbosa, H., Marques Batista da Rocha, R., Barbosa Rodrigues, A. & Maiada Silva, V. Cáncer de próstata: conocimientos e interferencias en la promoción y prevención de la enfermedad. Enfermería Global. [Internet]. 2019 [obtenido: el 14 de octubre de 2022]. 18(54), 250-284. Disponible en: https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.18.2.336781 [ Links ]

10. Tapia Benavente, L., Vergara Merino, L., Garegnani, L.I., Ortiz Muñoz L., Loézar, C. & Vargas Peirano M. Revisiones rápidas: definiciones y usos. Medwave. [Internet]. 2021 [obtenido el 10 de septiembre de 2020]; 21(01) Disponible en https://www.medwave.cl/revisiones/metodinvestreport/8090.html [ Links ]

11. Carbó, A.C. Randomized clinical trials (CONSORT). Medicina clínica. [Internet]. 2005 [obtenido: el 15 de noviembre de 2022] Disponible en: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-atencion-primaria-27-articulo-consort-un-intento-mejorar-calidad-15080 [ Links ]

12. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Medicine [Internet]. 2009 Jul 21 [obtenido: el 16 de noviembre de 2022];6(7):e1000097. https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [ Links ]

13. Islas Pérez L.A., Martínez Reséndiz J.I., Ruiz Hernández A., Ruvalcaba Ledezma J.C., Benítez Medina A., Beltran Rodríguez M.G., Yáñez González A., Rivera Gómez M.C., Jiménez Sánchez R.C. & Reynoso Vázquez J. Epidemiología del cáncer de próstata, sus determinantes y prevención. Journal of Negative no Positive Results [Internet]. 2020 [obtenido: el 29 de noviembre de 2022]; 5(9):1010-22. Disponible en: DOI: https://doi.org/10.19230/jonnpr.3686 [ Links ]

14. Abhar, R., Hassani L., Montaseri M. & Ardakani M.P. The Effect of an Educational Intervention Based on the Health Belief Model on Preventive Behaviors of Prostate Cancer in Military Men. [Internet]. 2022 Community Health Equity Res Policy. [obtenido: el 28 de octubre de 2022]; 42(2) 127-134. Disponible en https://doi.org/10.1177/0272684X209741 [ Links ]

15. Mbugua Ruth G., Karanja S. & Oluchina S. Effectiveness of a Community Health Worker-Led Intervention on Knowledge, Perception, and Prostate Cancer Screening among Men in Rural Kenya. Advances in Preventive Medicine. [Internet]. 2021 [obtenido: el 29 de octubre de 2022]; 27, 1-10 Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4621446 [ Links ]

16. Hidalgo Ávila, M., Purón Prieto, J., Vega Lorenzo, Y., Martínez Lorenzo, F. Y. & Leyva Guerra, Y. Intervención educativa sobre cáncer de próstata en la población de 50 años y más. Jornada virtual de medicina familiar en ciego de Ávila. [Internet]. 2021 [obtenido: el 07 noviembre del 2022]; Disponible en: https://mefavila.sld.cu/index.php/mefavila/2021/paper/download/ [ Links ]

17. Saleh, A.M., Ebrahim E.E., Aldossary, E.H. & Mazyad Almutairi, M.A. The Effect of Prostate Cancer Educational Program on the level of Knowledge and Intention to Screen among Jordanian Men in Amman. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. [Internet]. 2020 [obtenido el 18 de noviembre de 2022]; Disponible en https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31983186/ [ Links ]

18. Rezaei H., Negarandeh R., Pashaeypoor S. & Kazemnejad A. Effect of educational program based on the theory of planned behavior on prostate cancer screening: A randomized clinical trial. International Journal of Preventive Medicine. [Internet]. 2020. [obtenido el 8 de noviembre de 2022]; 11:146. Disponible en: https://www.ijpvmjournal.net/text.asp?2020/11/1/146/294695 [ Links ]

19. Martin R.M, Donovan J.L., Turner E.L., et al. Effect of a Low-Intensity PSA-Based Screening Intervention on Prostate Cancer Mortality. JAMA. 2018. [ Links ]

20. Richard M.M., Donovan J.L., Turner E.L., et al. Effect of a Low-Intensity PSA-Based Screening Intervention on Prostate Cancer Mortality. The CAP Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of the American Medical Association [Internet]. 2018 [obtenido el 14 de noviembre de 2020]; disponible en: doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0154 [ Links ]

21. Smith Hernández, M. S., Sánchez Smith L. I., López Enamorado Y., Lastres Fonseca, L., Enamorado Tamayo, A.L., & Enamorado Piña, G.V. Intervención Educativa sobre Factores de Riesgo del Cáncer de Próstata. [Internet]. 2020. I Congreso Virtual de Ciencias Básicas Biomédicas de Granma. Disponible en: http://cibamanz2020.sld.cu/index.php/cibamanz/cibamanz2020/paper/view/477/256 [ Links ]

22. Jeihooni K. A. & Kashfi Mansour S. The Effect of Educational Program Based on PRECEDE Model in Promoting Prostate Cancer Screening in a Sample of Iranian Men. Journal of Cancer Education. [Internet]. 2019 [obtenido: el 16 de noviembre del 2022]; Disponible en: DOI 10.1007/s13187-017-1282-8 [ Links ]

23. Pérez García, K., Ronquillo Paneca, B., Coronel Carbajal C., & Abreu Viamontes C. Intervención educativa sobre cáncer de próstata en población masculina entre 40 a 60 años. [Revista Archivo Médico de Camagüey. Internet] 2018 [Obtenido: el 05 de octubre 2022]; 9-16. Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/2111/211159706004/html/ [ Links ]

24. Molazem Z., Ebadi M., Khademian M. & Zare R. Effects of an Educational Program for Prostate Cancer Prevention on knowledge and PSA Testing in Men Over 50 Years old in Community Areas of Shiraz in 2016. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. [Internet]. 2018 [obtenido: el 19 de noviembre de 2022]; Mar 27;19(3):633-637. Disponible en doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.3.633. [ Links ]

25. Ghodsbin, F., Zare M., Jahanbin, I., Ariafar, A, Keshavarzi S. & Izadi T. The Effect of Health Belief Model-Based Education on Knowledge and Prostate Cancer Screening Behaviors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Community-Based Nursing and Midwifery. [Internet]. 2016 [obtenido: el 19 de noviembre de 2022]; 4(1):57-68. Disponible en PMID: 26793731; PMCID: PMC4709816. [ Links ]

Received: December 17, 2022; Accepted: March 05, 2023

texto em

texto em