STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS

Stakeholder analysis involves the efficient gathering and analyzing of qualitative information by engaging identified players in a specific sector, in this case, the healthcare sector of Namibia, to determine whose interests should be considered when developing a policy or program and/or in the post/pre-implementation phase of a policy or program [1]. This approach also assists in identifying gaps that might exist within the sector under examination.

Pharmacovigilance systems are criritical for holistic health care delivery; this is not the case in most countries in sub-Saharan Africa. In Namibia, pharmacovigilance is coordinated by a national Therapeutic Information and Pharmacovigilance Centre (TIPC), with minimal and incosnsistent engagement of key stakeholders [2]. This approach has limited impact on the pharmacovigilance practice culture within public and private healthcare sectors, and among the populace at large.

This paper highlights the potential and defines roles of stakeholders critical to the strengthening of pharmacovigilance systems in Namibia. It also proposes a conceptual framework within which the different stakeholders can operate to the benefit of the central focus of pharmacovigilance, which is the patient.

National regulatory authorities (NRAs) are saddled with the responsibility of ensuring the safety, efficacy and quality of medicines that are registered and eventually found their ways into market place; this has a direct impact on the health and health status of the populace being served by such NRAs. The strength or capacity of NRAs to monitor medicine safety in sub-Saharan Africa depends on the quality of collaborative efforts that the entity can garner within the existing health system and among allied entities related to it [3]. Pharmacovigilance systems require a multi-sectorial approach for them to achieve the goal of better patient management and the end result of a reduction in costs due to adverse events [4]. Such a multi-sectorial approach has been successful tackling public health issues like HIV/AIDS pandemic [5]. It is important to understand the drivers of the pharmacovigilance system within a country and how to engage suc entities in ensuring better health status of the population [6].

WHO IS STAKEHOLDER IN THE PHARMACOVIGILANCE SYSTEM?

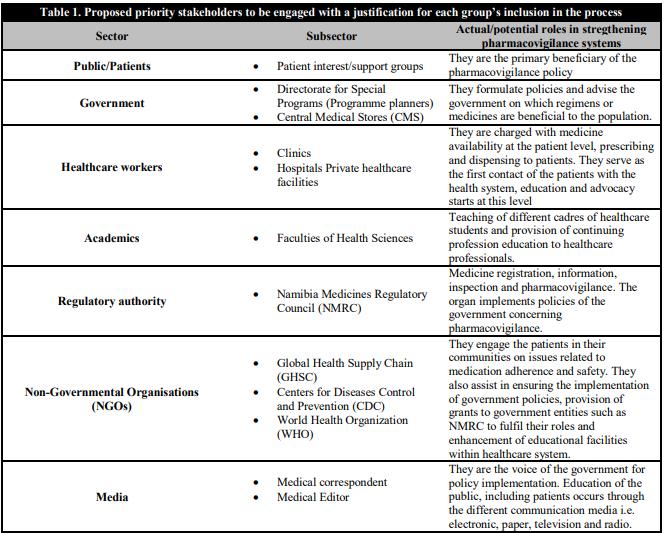

Stakeholders in a process are actors (persons or organizations) with a vested interest in the policy being promoted [7]. These stakeholders, or “interested parties,” can be grouped into the following categories: international donors, national or local politicians (legislators, governors, local government chairpersons), public (Ministry of Health and Social Services [MoHSS] and local government staff, policymakers and technocrats, social security agencies, professional associations, including labour unions, healthcare providers, both commercial and private non-profit organisations (non-governmental organizations, civil society, and users/consumers, individuals and beneficiaries). Table 1 depicts the possible stakeholders within the health system and their roles in enhancing pharmacovigilance systems in Namibia.

Table 1. Proposed prioriy stakeholders to be engaged with a justification for each group's inclusion in the process

In a bid to strengthen the pharmacovigilance systems in Namibia, we believe it is necessary to analyse and conceptualise how these stakeholders can be engaged. This will help policymakers and healthcare managers at different levels of the health system, work out better ways of optimising pharmacovigilance and adverse drug reactions (ADR) reporting by healthcare workers and patients. This analysis can assist MoHSS to detect and act to prevent potential shortcomings about and/or opposition to a pharmacovigilance policy or related programs in focus.

PROPOSED STRATEGY FOR ANALYSIS OF STAKEHOLDER INVOLVMENT IN PV

Qualitative data will be generated during stakeholder analysis, this will assist in identifying drivers of pharmacovigilance within and outside the healthcare sector. The data will be collected through face to face interviews which will be arranged with the different identified individuals within the various stakeholder groups over a period of time. Semi-structured questions will be developed, bordering around strengthening, awareness and analysis of the Strenght, Weakness, Opportunity and Threats (SWOT) to the current pharmacovigilance systems as perceived by the stakeholder group; however, interviewees will be allowed to cover more areas of the pharmacovigilance system that is not included in the developed questions.

A recording machine or paper-based record will be used to gather/collect data during the interview sessions. The data collected will be transcribed and common themes will be identified to allow for data synthesis, interpretations and analysis.

Respondents will be contacted by phone and through emails for their consent to be included in the stakeholder engagement study and also, to schedule meeting time suitable to them. Confidentiality of the respondents will be maintained and no marker identifiable to the respondents will be retained or collected during the interview period and after the interview.

MODEL QUESTIONS

How do you perceive the current pharmacovigilance systems in Namibia can be improved?

-

Who

Who should be taken on board to ensure better or strengthened pharmacovigilance systems in Namibia?

Where do you think pharmacovigilance should be practiced?

What should be the content of a pharmacovigilance policy, bearing in mind Namibian Patient Charter?

ENGAGING THE STAKEHOLDERS

Apart from the key informant interviews, focus group meetings will be held in various regions of Namibia, with substantial patient representation, as well as healthcare practitioners from both public and private healthcare settings.

It is hoped that the results of this study will reveal salient issues pertaining to pharmacovigilance in Namibia. Through the creation of awareness, greater involvement of policymakers at different levels of governance. Also, it can shed more insight into how different stakeholders thought their impact can be felt.