Several meta-analyses conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of batterer intervention programs (BIPs) have indicated that the effect size of these interventions on reducing recidivism tends to be small (Arce et al., 2020; Babcock et al., 2004; Cheng et al., 2019; Eckhardt et al., 2013; Feder & Wilson, 2005; Smedslund et al., 2011). This limited success of BIPs in reducing recidivism has been attributed to different factors such as low treatment compliance and high dropout rates (Bennett et al., 2007; Daly & Pelowski, 2000; Jewell & Wormith, 2010; Lila et al., 2019; Olver et al., 2011), lack of motivation for change (Carbajosa, Catalá-Miñana, Lila, & Gracia, 2017; Carbajosa, Catalá-Miñana, Lila, Gracia, et al., 2017; Crane et al., 2015; Eckhardt et al., 2008; Zalmanowitz et al., 2013), problems in building the working alliance (Cadsky et al., 1996; DiGiuseppe et al., 1994; Murphy & Baxter, 1997; Taft et al., 2004), and poor engagement in program activities (Musser et al., 2008; Taft et al., 2003).

Motivational strategies are one of the approaches to overcome these limitations and, consequently, to improve the effectiveness of BIPs (Babcock et al., 2016; Feder & Wilson, 2005; Santirso et al., 2020). Among the motivational strategies included in BIPs are, for example, interventions based on the ‘stage of change' approach (Alexander et al., 2010), retention techniques (Mbilinyi et al., 2011; Musser et al., 2008; Taft et al., 2001), or motivational interviewing (Alexander et al., 2010; Crane & Eckhardt, 2013; Kistenmacher & Weiss, 2008; Lila et al., 2018; Mbilinyi et al., 2011; Murphy et al., 2017; Musser et al., 2008; Scott et al., 2011; Woodin & O'Leary, 2010). A growing body of research reports promise results regarding the effectiveness of BIPs incorporating motivational strategies, in terms of decreasing intimate partner violence recidivism and levels of dropout (Alexander et al., 2010; Crane & Eckhardt, 2013; Lila et al., 2018; Mbilinyi et al., 2011; Murphy et al., 2017; Scott et al., 2011; Taft et al., 2001; Woodin & O'Leary, 2013) and increasing intervention attendance, homework compliance, and stage of change level (Crane & Eckhardt, 2013; Kistenmacher & Weiss, 2008; Lila et al., 2018; Murphy et al., 2017; Musser et al., 2008; Taft et al., 2001).

Motivational strategies aim to build a strong facilitator-participant working alliance that helps to reduce participants' intervention resistance and increase motivation for change (Stuart et al., 2007). Also, these strategies are likely to promote protherapeutic behaviors among participants, thus leading to an improved group climate in BIPs (Brown & O'Leary, 2000; Musser et al., 2008; Rondeau et al., 2001; Semiatin et al., 2013; Taft et al., 2003; Taft et al., 2004).

The working alliance, according to Bordin (1979), consists of three components: facilitator-participant agreement on the intervention goals, participants' acceptance of and collaboration with the tasks proposed by facilitators to address participants' problems, and facilitator-participant emotional bond. The working alliance has been related to physical and psychological IPV reduction. For example, using observers' scores, Brown and O'Leary (2000) found that the working alliance in the first sessions of a voluntary couple intervention on IPV was associated with significant reductions of physical and psychological violence at the end of the intervention. In a court-mandated group intervention to prevent IPV, Taft et al. (2003) found that the therapeutic alliance reported by the therapist was also related with significant reductions of physical and psychological violence at six-month follow-up.

As for protherapeutic behaviors in the context of BIPs, Semiatin et al. (2013) defined them in terms of participants' verbalizations indicating: a) acknowledgment of personal responsibility and the need for personal change to avoid future violent behavior; b) participants' role behavior facilitating positive changes of other group members; and c) participants' verbalizations indicating a positive perception of both the group and the intervention program. These protherapeutic behaviors have been related to a significant reduction of physical and psychological IPV reported by victims at six-month follow-up (Semiatin et al., 2013).

However, despite the importance of these key intervention processes, little research has been conducted to assess the effectiveness of motivational strategies on increasing participant-facilitator working alliance and participants' protherapeutic behavior in BIPs.

The Present Study

The main aim of the present study was to examine whether adding motivational strategies to a standard BIP increases participant-facilitator working alliance and participants' protherapeutic behaviors. To this end, a randomized controlled trial was conducted, comparing a standard BIP (control group) with an experimental condition in which an individualized motivational plan was added to the standard BIP as a motivational strategy (IMP; Lila et al., 2018; Romero-Martínez et al., 2019). The IMP is based on several approaches aimed at increasing intervention compliance in BIPs that have proved their effectiveness in different settings: motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 2002), stages of change approach (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1982; Prochaska et al., 1992), solution-focused brief therapy (De Shazer & Berg, 1997), and the Good Lives model (Langlands et al., 2009; Ward, 2002). The main components of the IMP are: (1) five individual motivational interviews, of which three were conducted during the evaluation phase to reduce participants' resistance to the intervention and establish participants' personal goals, one was conducted in the middle of the program to monitor their progress, and the last one was conducted around the end of the program to assess their achievements; (2) three group sessions, where participants share their personal goals, explain their progress to the group, and receive feedback, support, and advice from facilitators and other group participants (these group sessions are conducted at the beginning, middle, and end of the program); (3) facilitators follow-up and reinforcement of participants' goals in every weekly group session throughout the intervention; and (4) retention techniques, such as phone calls when participants miss a group session. The IMP also implies that facilitators adopt an empathic and motivational attitude throughout the intervention, creating a climate of acceptance and using confrontation only when it becomes absolutely necessary.

As far as we know, the only previous experimental study analyzing whether motivational strategies increase working alliance and protherapeutic behaviors in BIP participants was conducted by Musser et al. (2008). In their study, groups receiving two motivational interviewing sessions as a pretreatment intervention were compared to control groups (i.e., intake as usual, without motivational interviewing). These researchers observed in the experimental group an increase in protherapeutic behaviors (i.e., verbalizations of responsibility for abusive behavior and group intervention usefulness) and higher working alliance late in intervention rated by therapists.

The present study pulls ahead previous research in two relevant issues, one related to the implementation of motivational strategies and the other related to the assessment of both protherapeutic behaviors and working alliance. First, in our study the motivational strategy was delivered throughout the BIP and not only as pretreatment intervention. We expected that the higher the exposure to motivational strategies the more positive the effect on the working alliance and protherapeutic behaviors. Second, we used a systematic observational methodology conducted by external observers to assess both protherapeutic behaviors and the working alliance. This methodological approach addressed impression management and social desirability issues when using offenders' self-reports, as well as potential biases in facilitators' self-reports or observations (Bennett, 2007; Gracia et al., 2015; Juarros-Basterrechea et al., 2018; Santirso et al., 2018; Weber et al., 2019).

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 153 males convicted of intimate partner violence against women and court-mandated to a community-based BIP. Offenders had been sentenced to less than a two-year term in prison, did not have previous criminal records, and their sentence was suspended on the condition that they attended the intervention. Eligibility criteria for this study were the following: (a) men over 18 years of age, (b) who had no severe psychological disorder, (c) had no severe substance abuse problems, and (d) had signed an informed consent form. Mean age was 40.73 years (SD = 11.99, range: 18-78). The sample consisted primarily of Spanish (71.7%, n = 110), Latin American (n = 17, 11.2%), European (other than Spanish, n = 13, 8.6%), African (n = 11, 7.2%), and Asian (n = 2, 1.3%) males. Regarding educational level, 6.4% had no education, 51% had primary education, 31.5% had secondary education, and 11.1% had university education. As for marital status, 33.3% were single (n = 51), 32.7% were divorced (n = 50), 24.2% were married or in a relationship (n = 37), and 9.8% were separated (n = 15). On average, annual family household income was between €6,000 and €;12,000. About half of the participants were unemployed 45.1% (n = 69) at the time of the initial assessment.

Intervention Conditions

Standard batterer intervention program (SBIP). This condition consisted of 35 weekly group sessions of a standard cognitive-behavioral intervention. It was divided into six modules with the following main aims: a) first module: to build a climate of trust and establish norms for the group to function; b) second module: to introduce the IPV basic concepts and address attribution of responsibility; c) third module: to train in cognitive emotion management techniques and cognitive restructuring; d) fourth module: to develop awareness of IPV consequences on victims, empathy, and positive communication skills in intimate relationships; e) fifth module: to discuss sexist attitudes, gender roles, and gender equality; and f) sixth module: to consolidate learning objectives and prevent relapse. Several techniques were applied during the SBIP (i.e., group dynamics, role-playing, monitored exercises, and training in cognitive restructuring or emotion management skills). Closed-ended groups in both conditions ranged from 10 to 12 men per group and were led by two facilitators.

Standard batterer intervention program plus individualized motivational plan (SBIP + IMP). The experimental condition consisted of the same standard cognitive-behavioral intervention with the addition of the IMP (see description above).

Facilitators training and intervention adherence. Facilitators were psychologists with at least two years' experience in BIPs. They received approximately 25 hours of training in their respective intervention condition. Facilitators were blind to the intervention condition. Each pair of facilitators intervened exclusively on one intervention condition. Facilitators for each condition were supervised independently once every two weeks. Supervision sessions focused on adherence to treatment protocol, group management, participants' progress, and preparation of future sessions. To ensure the content of and adherence to the protocol, written intervention manuals for each condition were used (Lila et al., 2018).

Randomization. Participants assessed for eligibility came through the penitentiary system (N = 181). Twenty-eight men were excluded, mainly for not attending the first meeting (see Figure 1). A random number generator was used to allocate participants to the SBIP or the SBIP + IMP condition. Fourteen intervention groups were established, seven for the SBIP + IMP condition (n = 74) and seven for the SBIP condition (n = 79). Figure 1 provides the description of participant flow from recruitment to study completion.

Procedure

Participants were clearly told that refusing to participate in the study would not affect their legal situation and would have no legal consequences. Confidentiality was assured, with the sole exception of situations that could pose a risk to participants or other people. Participants who agreed to take part in this study completed a written consent form and were randomly assigned to the SBIP + IMP or SBIP condition. Four independent trained graduate research assistants, who were blind to the objectives and hypotheses of the study, coded videotaped sessions. Working alliance and protherapeutic group behaviors were assessed twice: early in intervention (sessions 3-7) and late in intervention (sessions 24-28). Raters previously underwent training in which they assessed the same recorded session separately until they reached an acceptable level of agreement (i.e., not differing by more than one point on each assessed item). Two-hour recorded intervention sessions were divided into 24 five-minute intervals. Each participant received an average rating across session intervals on working alliance and protherapeutic group behaviors.

Measures

Working Alliance Inventory-Observer short version (WAI-O-S; Tichenor & Hill, 1989; Spanish version by Santirso et al., 2018). This observational scale assesses both general working alliance, and two components of working alliance (i.e., agreement and bond). The WAI-O-S contains 12 items (e.g., "There is a mutual liking between participant and facilitator", "There is agreement on what is important for the participant to work on"). Raters responded on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (conclusive evidence against) to 7 (conclusive evidence in favor). The scale had adequate internal consistency in this study with Cronbach's alpha equal to .97 and .92 for early and late in intervention measures, respectively. In a previous study with a sample of male IPV offenders, results showed an excellent level of inter-rater agreement and significant correlations with other indicators of intervention effectiveness (e.g., stage of change, motivation to change, and protherapeutic group behaviors; see Santirso et al., 2018).

Observational coding of protherapeutic group behavior (Semiatin et al., 2013). This observational tool assesses protherapeutic behaviors of group participants through their verbalizations. It is a 3-item measure of the following protherapeutic behaviors: (a) responsibility for abuse—participants' verbalizations related to assuming vs. denying responsibility for their abusive actions, consequences of these actions, and the need for a personal change to avoid committing abusive acts in the future; (b) participant role behavior—interpersonal behaviors within the group that promote or hinder change by other participants; the coding system addressed four types of participant role behavior along two axes, confirmation vs. confrontation and negative progress vs. positive progress; and (c) group value—participant verbalizations related to the perceived value of the group and the intervention in general. Raters assessed each of the protherapeutic behaviors on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (conclusive evidence against) to 5 (conclusive evidence in favor). The effect of different raters assessing the same participants was evaluated. Pooled reliability correlation (r) across the three coded variables for averaged session ratings was .53, n = 30, p = .011.

Statistical Analyses

To analyze whether participants who received SBIP + IMP and participants who received SBIP were equivalent at the time of allocation, chi-square and independent t-tests were conducted for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. To assess ‘time' and ‘group' differences in working alliance and protherapeutic behavior, we carried out repeated measures ANOVAs, with working alliance and protherapeutic group behaviors (early and late in intervention) as between-subject factors, and ‘intervention group' (SBIP + IMP or SBIP) as the within-subject factor. When a factor was significant in previous ANOVAs, Bonferroni tests were performed. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0, and two-tailed tests with p set to .05 were considered as significant.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

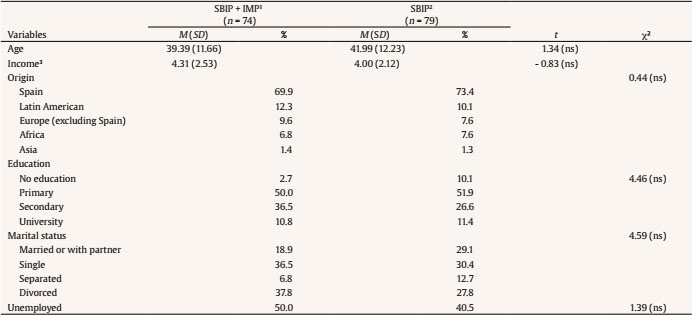

Table 1 contains information on sociodemographic characteristics by treatment condition. The results showed that randomization was satisfactory. No pretreatment characteristics significantly distinguished SBIP + IMP and SBIP groups.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Participants in Each Intervention Condition (N = 153)

Note. 1SBIP + IMP = standardized batterer intervention program plus individualized motivational plan; 2SBIP = standardized batterer intervention program; 3annual income: 1 = < €1,800; 2 = €1,800-€3,600; 3 = €3,600-€6,000; 4 = €6,000-€12,000; 5 = €12,000-18,000; 6 = €18,000-€24,000; 7 = €24,000-€30,000; 8 = €30,000-€36,000; 9 = €36,000-€60,000; 10 = €60,000-€90,000; 11 = €90,000-€120,000; and 12 = > €120,000..

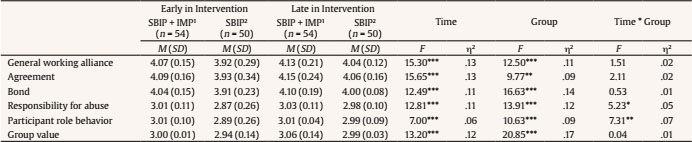

Observational Ratings of Working Alliance and Protherapeutic Group Behaviors

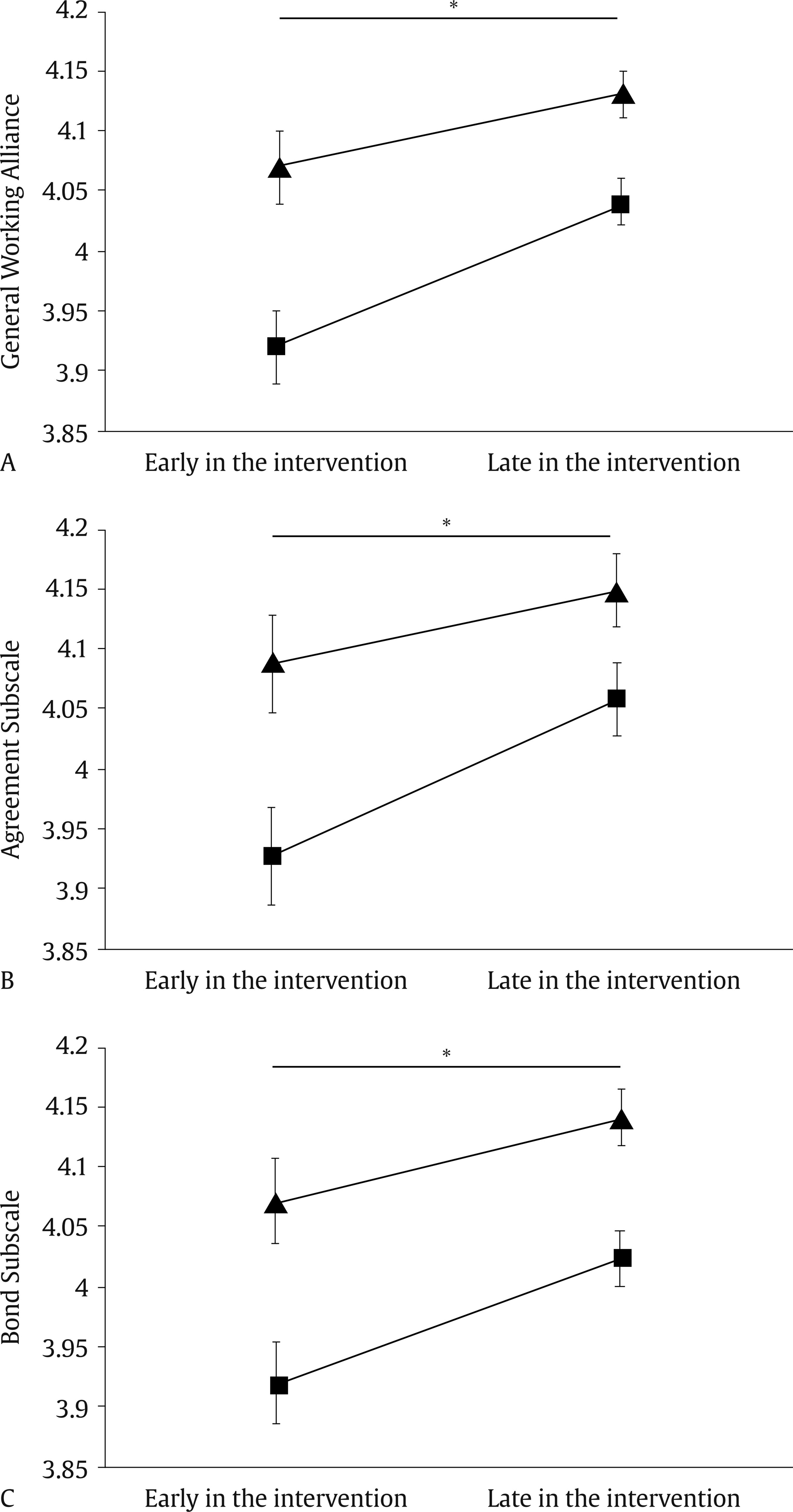

There was a significant effect of ‘time' on general working alliance, and on the agreement and bond subscales, F(1, 102) = 15.30, p = .0001, η2 = .13; F(1, 102) = 15.65, p = .0001, η2 = .13; F(1,102) = 12.49, p = .001, η2 = .11, respectively, with higher scores later in intervention than early in intervention in the total sample (see Table 2). A significant effect of ‘group' was also found on general working alliance, and on agreement and bond subscales, F(1, 102) = 12.50, p = .001, η2 = .11; F(1, 102) = 9.77, p = .002, η2 = .09; F(1, 102) = 16.63, p = .0001, η2 = .14, respectively. Size effects were moderate to large (Cohen, 1988). Participants who received SBIP + IMP intervention showed higher general working alliance than those who received SBIP intervention, regardless of intervention moment (see Table 2 and Figure 2). No other significant effects were found on working alliance.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics and 2 x 2 Repeated Measures ANOVAs for Completers Sample (n = 104)

Note. SBIP + IMP1 = standardized batterer intervention program plus individualized motivational plan; SBIP2 = standardized batterer intervention program.

* p ≤ .05,

** p ≤ .01,

*** p ≤ .001.

* Effect of group (SBIP + IMP or SBIP) (p < 0.05).

Figure 2. Working Alliance Scores Early in Intervention and Late in intervention in SBIP+IMP group (represented by triangles) and SBIP group (represented by squares). a) General working alliance; b) Agreement subscale; c) Bond subscale.

Additionally, a significant effect of ‘time' was found on responsibility for abuse, participant role behavior, and group value scores, F(1, 102) = 12.81, p = .001, η2 = .11; F(1, 102) = 7.00, p = .009, η2 = .06; F(1, 102) = 13.20, p = .0001, η2 = .12, respectively, with higher scores late in intervention compared to early in intervention in the total sample (see Table 2). Moreover, a significant ‘group' effect was found on responsibility for abuse, participant role behavior and group value scores, F(1, 102) = 13.92, p = .0001, η2 = .12; F(1, 102) = 10.63, p = .002, η2 = .09, F(1, 102) = 20.85, p = .0001, η2 = .17, respectively, with participants who received SBIP + IMP having higher scores (see Figure 3). Size effects were moderate to large (Cohen, 1988). Furthermore, a significant ‘time * group' effect was found on responsibility for abuse and participant role behavior scores, F(1, 102) = 5.23, p = .02, η2 = .05; F(1, 102) = 7.31, p = .008, η2 = .07, respectively (see Table 2 and Figure 3). Specifically, participants who received SBIP + IMP intervention showed higher responsibility for abuse early (p = .001) and late in intervention (p = .013) than those who received SBIP. Additionally, participants who received SBIP + IMP condition had significantly higher participant role behavior scores (p = .002) and tended to show higher participant role behaviors scores late in treatment than those who received SBIP only (p = .067). Finally, responsibility for abuse and participant role behaviors significantly increased throughout intervention in participants who received SBIP (for all, p < .0001), but not in those in SBIP + IMP condition (for all, p > .35).

* Effect of group (SBIP + IMP or SBIP) (p < 0.05). * Effect of ‘time*group' (p < 0.05). (t) Effect of ‘time*group' (p = 0.067).

Figure 3. Protherapeutic Group Behavior Early in Intervention and Late in Intervention in SBIP+IMP group (represented by triangles) and SBIP group (represented by squares). a) Responsibility for abuse; b) Participant role behavior; c) Group value.

Discussion

Working alliance and protherapeutic behaviors are key intervention processes to improve BIP effectiveness. Motivational strategies can contribute to build a strong working alliance and promote protherapeutic behaviors. However, little rigorous research has been conducted to assess the effectiveness of motivational strategies to increase working alliance and participants' protherapeutic behavior in BIPs. The randomized controlled trial conducted in this study showed that adding motivational strategies to a standard BIP increases participant-facilitator working alliance and participants' protherapeutic behaviors.

Our results showed that both general working alliance and scores on the agreement and bond subscales increased significantly over the course of the intervention in both intervention conditions, and was significantly higher in the SBIP + IMP intervention condition (both early and late in intervention). The results indicate that using an IMP helps to establish an agreement between IPV offenders and facilitators on BIPs' objectives and tasks. Reaching this agreement is a challenge in BIPs, as IPV offenders tend to minimize or fail to recognize acts of violence for which they have been convicted (Flinck & Paavilainen, 2008; Lila, Oliver, Catalá-Miñana, & Conchell, 2014; Martín-Fernández et al., 2018; Murphy & Maiuro, 2009; Weber et al., 2019). For example, they do not recognize that their anger is problematic, and tend to attribute responsibility for their abusive actions to their partner or the legal system, believing that they have been treated unfairly and that they are the main aggrieved party (DiGiuseppe et al., 1994; Murphy & Maiuro, 2009; Vitoria-Estruch et al., 2017). In addition, most of these men are court referred or enter intervention as a result of external pressure (Daly & Pelowski, 2000; Velonis et al., 2016). Motivational strategies seem to overcome some of these difficulties by establishing a collaborative environment and helping participants to establish self-determined goals through the exploration of potential benefits of change (Lee et al., 2014; Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Regarding bond, Safran and Muran (2000) stressed the importance of participants' trust in facilitators' ability to help them throughout the intervention. Among the basic intervention principles of motivational strategies, such as the IMP, is the acceptance of participant resistance as part of the change process (Murphy & Maiuro, 2009). This attitude of accepting resistance and supporting participants' self-efficacy facilitates and strengthens the bond between a facilitator and a participant.

As for protherapeutic behaviors, our results showed that assumption of responsibility was significantly higher in the SBIP + IMP intervention condition (both early and late in intervention). Participants in the SBIP + IMP condition recognized more frequently within the group their responsibility for the violence, its consequences on people around them, and the need to make personal changes to avoid committing abusive acts in the future. Non-confrontational, non-judgmental, and empathetic listening qualities of motivational strategies may explain this increase in participants' assumption of responsibility (Musser et al., 2008; Taft & Murphy, 2007). In fact, the framework of motivational interviewing is that participants feel accepted despite the presence of some unacceptable behaviors (Murphy & Maiuro, 2009). Concerning early in intervention participant role behavior, offenders in the SBIP + IMP intervention condition showed significantly greater efforts to help other members of the group to change and to assume responsibility for their behavior. For example, participants in the SBIP + IMP group more frequently confronted other group members' comments about avoiding responsibility by blaming their partner or the legal system, or reinforced assumptions of responsibility of other group members (Gracia, 2014; Henning & Holdford, 2006; Lila, Oliver, Catalá-Miñana, Galiana, et al., 2014; Martín-Fernández et al., 2018). Regarding group value, participants in the SBIP + IMP intervention condition were more likely to make positive assessments of the group, and the intervention in general, both early and late in intervention.

The results of our study highlight the importance of using motivational strategies in order to increase their impact on both participant-facilitator working alliance and participants' protherapeutic behaviors. Our study pulls ahead previous research on the importance of motivational strategies to increase the effectiveness of BIPs (Musser et al., 2008) at least in three aspects. First, in our study, motivational strategies were implemented throughout the intervention program. Other studies tend to implement motivational strategies only at pre-intervention stage. However, as our results showed, a more extensive implementation of motivational strategies can lead to more long-lasting gains (Crane & Eckhardt, 2013; Musser et al., 2008; Santirso et al., 2020; Stuart et al., 2013). This idea is also supported by research on other behavior change interventions. For example, a systematic review of the effectiveness of motivational interviewing on substance abuse, gambling, health-related behaviors, and engagement in intervention showed a positive association between the motivational intervention dose and its efficacy (Lundahl et al., 2010). Second, in our study we assess both protherapeutic behaviors and working alliance using a systematic observational methodology conducted by external observers. This methodological approach allows researchers to address important limitations that arise when using offenders' self-reports (i.e., impression management or social desirability). This approach also overcomes potential biases in facilitators' reports (Bennett, 2007; Gracia et al., 2015; Santirso et al., 2018). For example, previous research reports different results depending on the source of information, such as participants or facilitators (Musser et al., 2008). Third, facilitators used in our study were psychologists with at least two years' experience in managing BIPs. Facilitators' experience can be a major factor in the implementation quality of motivational strategies (Hamel et al., in press).

As for limitations, although manuals for each condition were used to ensure the content of and adherence to the protocol, and facilitators were regularly supervised, the IMP protocol was not quantitatively rated by an external observer. Also, this study was conducted with IPV offenders court-mandated to a community-based BIP. This could limit the generalizability of our results to other population samples such as men attending voluntary programs, men imprisoned for IPV, women who have committed IPV, or individuals with severe substance abuse problems or psychological disorders. Despite these limitations, this is the first RCT evaluating the effectiveness of a motivational strategy implemented throughout the intervention program—IMP—on the participant-facilitator working alliance and participants' protherapeutic behaviors. Our findings have important practical implications, as our results clearly showed that a motivational strategy tool such as the IMP improves key intervention processes (i.e., working alliance and protherapeutic behaviors) in BIPs, therefore increasing their effectiveness.