Introduction

School violence and cyberbullying are two of the social and public health problems of most worldwide concern in education, organizations, and interpersonal relations (Bjärehed et al., 2019; Dennehy et al., 2020; Doumas & Midgett, 2020; Ng, 2019; Ruiz-Hernández et al., 2020; Viejo et al., 2020) along with substance use (Fernández-Artamendi et al., 2021; Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2021; Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2020). Violence on electronic devices and social networks has become one of the phenomena most studied in recent years (Barragán et al., 2021; Carvalho et al., 2021; Nasaescu et al., 2020). Cyberbullying consists of harm caused to another person through the repeated use of information and communication technologies (texting, social networks, calls, emails, etc.) by a person or group of persons (Kowalski et al., 2014; Nixon, 2014). In addition, its most outstanding characteristics are the possibility of carrying out such aggression at any time, anonymously, with a higher probability of an audience, and the physical distance separating victim and aggressor (Field, 2018; Wright et al., 2019). All these characteristics, along with the intentionality and power imbalance contribute to the growing prevalence of this phenomenon (Buelga et al., 2020; Kowalski et al., 2014), in which aggressors, victims, and observers are all involved.

Cyber-aggressors use the technology as a way to relieve their frustrations and generally have low self-esteem, problems expressing their emotions appropriately, and problems at school (Livazovic & Ham, 2019). The victims of cyberbullying intentionally harmed by the aggressor are usually introverted and timid, lacking social skills and social adaptation (Rodríguez-Álvarez et al., 2021). The lack of physical contact and unknown identity of the aggressor generate a feeling of desperation and helplessness in the victim that is worsened by the ease with which the harmful content quickly goes viral (Dong, 2020). Spectators are usually silent or defend the victim, although their opportunities for intervention in preventing cybervictimization are reduced, since most of the interactions are unsupervised and isolated, or they may even encourage the cyber-aggressor (Gardella et al., 2017). This type of behavior has become expected and accepted by youths as a relational and group process instead of considering individual differences (Menin et al., 2021). This study therefore focuses on the role of cyberbullying victims.

Studies to date have varied both in their conception of the phenomenon and how it is measured, although most have found that from 20% to 50% of youths have had at least one cyberbullying experience, increasing the number of cyber-victims (Garaigordobil, 2011; Garaigordobil, 2015; González-Calatayud & Prendes, 2021; Lee & Shin, 2017; Ortega-Barón et al., 2016). Victimization experiences are associated with adolescent wellbeing and behavior at school (Gardella et al., 2017). Factors such as age and gender have been evaluated in cybervictimization, although the results on the role of gender are not conclusive (Livazovic & Ham, 2019; Rodríguez-Domínguez et al., 2020). Kowalski and Limber (2007) emphasize that females are more prone to cybervictimization. Among the personality factors, cybervictimization is related positively to neuroticism (Alonso & Romero, 2017). Social intelligence acts as a protective factor against cybervictimization (Kowalski et al., 2014) and low cognitive empathy is a risk factor in cyberbullying behavior (Livazovic & Ham, 2019). Furthermore, emotional intelligence (Guerra et al., 2021; Quintana-Orts et al., 2021) and communication skills and parental control are protective factors (Feijóo et al., 2021), as is adolescent school adjustment (Rodríguez-Fernández et al., 2020).

Various studies have emphasized the negative consequences to adolescents who experience cybervictimization (Bauman et al., 2013; Fisher et al., 2016), especially psychological, behavioral, and educational problems (Brown et al., 2014), which differ from face-to-face victimization due to the role of technology in the adolescent's immediate environment (Bronfenbrenner, 1992). Thus, cyber-victimization is linked to more somatic complaints, and victims of cyberbullying tend to blame themselves (Rey et al., 2020), and say they feel anger, shame, and indifference. They also suffer from episodes of depression and anxiety, as there is a significant relationship between high levels of depression and stress and being the cyber-victim or aggressor (Martínez-Monteagudo et al., 2020). A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies on perpetration and victimization by cyberbullying found that the use of the internet along with anxiety and depression are predictors of cybervictimization (Marciano et al., 2020). Another study done on university students who had undergone cyberbullying in high school showed high levels of anxiety and depression (Jenaro et al., 2017). Similar results have been found in children and adolescents, where there is a significant relationship between cybervictimization, depression, and anxiety (Audrin & Blaya, 2020; Martínez-Monteagudo et al., 2020).

The main objective of this study was to analyze the relationship between cybervictimization, anxiety, and depression in an adolescent population through a meta-analysis, evaluate the heterogeneity and bias in publications, and identify the moderating variables that could help explain the various correlations.

Method

A review was made following the guidelines on preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) (Moher et al., 2015).

Data Sources and Searches

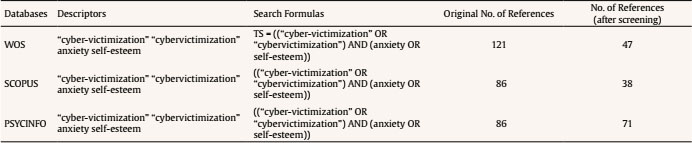

The search for publications was made in the Web of Science, Scopus, and PsycINFO databases on March 25, 2021. In all cases, the results were filtered by Open Access “journal articles” as the type of document, and the time period was limited from 2011 to 2021. Different specifications were made depending on the characteristics and coverage of the databases. In Web of Science, the search was limited to the term “theme” to refer to the title, abstract, and keywords. In Scopus and PsycINFO, the search was limited to title or abstract.

The search strategy consisted of combining Boolean operators with the following descriptors: “cybervictimization”, “cybervictimization”, “anxiety”, “self-esteem”, as shown in Table 1.

Study Selection

The bibliographic search was made separately by several researchers, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus or by consulting with another researcher. First, abstracts were examined to verify the articles that were relevant to the review, and then the complete text was evaluated to check that the articles met the following criteria: a) cross-sectional studies, b) studies with samples of adolescents aged 12 to 18, c) studies that provided empirical data on the cybervictimization, anxiety, and depression constructs, and d) studies published in English or in Spanish in scientific journals.

The exclusion criteria were: a) longitudinal studies, b) experimental studies, case studies, and controls or controlled trials, systematic reviews and meta-analyses, d) studies about variables other than anxiety and depression in the victims.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The following data were extracted from the articles selected for review: 1) basic study characteristics (authors, year and country), 2) sample characteristics (type of design sample size, age), and 3) correlation between the study variables (cybervictimization, anxiety and depression).

Quality was evaluated separately by two researchers using the STROBE checklist for evaluating the quality of reports on cross-sectional observational studies (Vandenbroucke et al., 2007).

Data Analysis

The meta-analysis was conducted using comprehensive meta-analysis (CMA) (ver. 3.0; Biostat, Englewood, New Jersey, USA) with the correlation coefficient.

To calculate the summary or combined r, and the 95% confidence interval, the test hypothesis was used to judge whether the correlation was statistically significant. In view of the differences in sample size, random effect models were used to calculate the correlation coefficient.

The heterogeneity between studies was evaluated using the Q-statistic (Cochran, 1954) and I2 was used to test the coherence between studies, because it does not depend on the number of articles. An I2 of 25% was interpreted as low inconsistency, 50% as moderate, and 75% as high (Higgins et al., 2003).

A forest plot was used to show the effect size and was interpreted in terms of the probability of superiority of the effect size and the effect incremental index, considering Cohen's (1988) effect size criteria: r ≈ .10 (small effect), r ≈ .30 (moderate effect), r ≈ .50 (large size). Nevertheless, the interpretation of the effect size in line with the Cohen's criteria suppose only a qualitative approach. Then, Cohen's categories were complemented with quantitative operationalizations: the probability of superiority of the effect size (PSES; Gancedo et al., 2021), consisting of the transformation of the effect size to a percentile, and the effect incremental index, an estimation of the effect due to the association between the variables over a trivial effect, .05 (EII; Fandiño et al., 2021). As for the significance of the observed mean correlation, with large samples (> 7,000) even trivial correlations result statistically significant. Hence, statistical significance was complemented with the met of the two following criteria (Arce et al., 2020): the confidence interval has no 0 and the lower limit of the true correlation (95% CI lower limit) should explain more than 1% of the variance (less than 1% is a trivial explanation).

Funnel graphs (Egger & Smith, 1995), Egger's regression intercept, the classic sail-safe N and Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill were used to evaluate bias in the publication. Meta-regression analyses were performed to examine the moderator variables such as mean age, standard deviation, percentage of females, year of publication, and continent.

Results

Search Results and Study Selection

The bibliographic search identified a total of 156 articles. Figure 1 shows the study selection process for the review. First, 44 duplicate studies were eliminated. Then, inclusion and exclusion criteria were set for the review of abstracts and later analysis of complete texts. This left 13 studies that met the selection criteria for the meta-analysis.

Characteristics of Studies Included

The articles selected were cross-sectional studies published from 2013 to 2020. Table 2 shows the detailed information for the review. The study population was mainly preadolescent and adolescents aged 8 to 19, except three, in which the sample included youth and adults.

The instruments used to measure cybervictimization were mainly the Cyber Peer Experiences Questionnaire (C-PEQ) (Landoll et al., 2013; Landoll et al., 2015), the Cyber-Bullying/Victimization Experiences Questionnaire (CBVEQ) (Kokkinos et al., 2013), the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire (ECIPQ) (Brighi et al., 2012; Del Rey et al., 2015), and other questionnaires on cyberbullying that evaluate cybervictimization, such as the Cyberbullying Screening of Peer Harassment (Garaigordobil, 2013, 2017), the Cyberbullying and Online Aggression Instrument (COAI; Hinduja & Patchin, 2008). The main instruments used to evaluate anxiety were the Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A; La Greca & Lopez, 1998) and the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (March et al., 1997). The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger, 1983), the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS; Mattick & Clarke, 1998) and the 21-item scale that evaluates depression, anxiety, and stress (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995; Daza et al., 2002). The main instrument for measuring depression was the Center for Epidemiological Studies - Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), although other studies used the Children's Depression Inventory (Kovacs, 1985), the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI II; Beck and Steer, 1984), or subscales of other instruments that measure this construct.

Of the 13 studies compiled for their analysis, about 54% were done in the United States, 15.4% in Spain and Greece, and the remaining 15.2% in Romania and Canada.

Correlation between Cybervictimization, Anxiety, and Depression

Figure 2 shows the forest plot of the relationships between cybervictimization and anxiety. A total of 13 studies with a total sample of 7, 348 were included in the analysis. The results of the meta-analysis showed a significant (p < .001, the 95% CI has no 0, and the lower limit of the CI explains 4% of the variance), positive and moderate magnitude (r ≈ .30) mean correlation between cybervictimization and anxiety, r = .31, 95% CI .20, .42]. The observed mean effect is higher than 74.2% (PSES = .742) of all possible effect sizes, implying an increase in the effect of 83.9% (EII = .839) over trivial. The Q-test showed heterogeneity (Q = 309.65, p < .001) with a high level of inconsistency (I2 = 96.12) between studies.

The meta-analysis of the 13 studies in the correlation analysis between cybervictimization and depression (Figure 3) revealed a significant (p < .001, the confidence interval has no 0, and the lower limit of the confidence interval explains 3.6% of the variance), positive, and of moderate magnitude (r ≈ .30) mean correlation coefficient of r = .28, 95% CI [.19, .36] for a total sample of 7,348. The observed mean effect is higher than 71.9% (PSES = .710) of all possible effect sizes, implying an increase in the effect of 82.8% (EII = .828) over trivial. In the Q-test, the results showed that there was heterogeneity (Q = 181.593, p < .001) with high inconsistency (I2 = 93.39) between studies.

Publication Bias

Figure 4 shows the funnel graph, where it may be observed there was no evidence of publication bias in the studies that evaluated the relationship of cybervictimization with anxiety and depression. Neither did the Egger's regression test (t = 0.02, p = .491) reveal any bias in publications. According to the results of the classic fail-safe N test, 8,036 studies would have to be included with a mean effect size of zero to cancel the effect size, demonstrating the total reliability of the effect size. According to the Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill test, both the fixed effects and the random effects models would have to add nine studies on the right-hand side to make the funnel graph symmetric.

Analysis of Moderator Variables

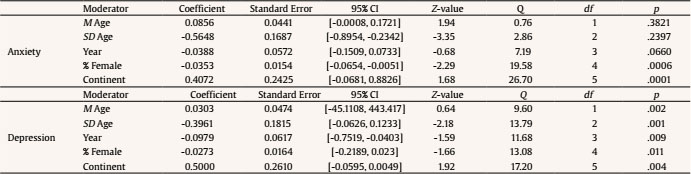

Given the heterogeneity of the studies, Table 3 examines mean age, standard deviation of age, year of publication, percentage of females, and the continent where the study was done as moderator variables.

In the meta-regression analysis, the test of individual variables showed that in the relationship between cybervictimization and anxiety, the percentage of females (Q = 19.58, df = 4, p < .001) and continent (Qb = 26.70, df = 5, p < .001) were significant moderators. The year of publication was tendential (Q = 7.19, df = 4, p = .0660) and the rest of the moderators were not significant. However, in the relationship with depression, all the moderators were significant: mean age (Q = 9.60, df = 1, p < .01), standard deviation of age (Q = 13.79, df = 2, p < .01), year of publication (Q = 11.68, df = 3, p <.01), percentage of females (Q = 13.08, df = 4, p < .01), and the place where the study was done (Q = 17.20, df = 5, p < .01) (see Table 3).

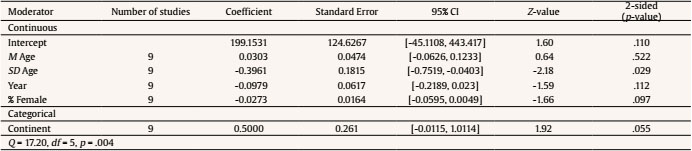

Table 4 shows the combined impact of all the covariates in the model with the Q statistic, where all the moderators of the sample characteristics were zero. In this case, with a Q = 26.70, df = 5, p = .000, the null hypothesis was rejected and we concluded that at least one of the covariates was related to the effect size. All the moderators were significant except year of publication and continent. This means that for each increase of one unit in mean age, the effect size would increase by .0856 (p = .0523) and other moderators were excluded. Likewise, for each increase in one unit in the percentage of females, the effect size would increase by -.0353 (p = .0219). The proportion of variance explained by this model was R2 = .78, which means that it was able to explain about 78% of the variance in the real effects.

Table 5 shows the moderator variables in the correlation between cybervictimization and depression. In this case, the null hypothesis was also rejected and it was concluded that at least one of the covariates was related to the effect size (Q = 17.20, df = 5, p = .004). In this sense, the significant moderators were the standard deviation of age, the percentage of females, and the continent where the study was done. Thus, each increase in one unit of the percentage of females and the standard deviation of age would increase the effect size by -.0273 (p = .097) and -.3961 (p = .029). Similarly, for each increase in the categorical variable continent, the effect size would increase by .5000 (p = .055).

Thus, the proportion of explained variance in this model was R2 = .50, which means that this model was able to explain around 50% of the variance in the real effects.

Discussion

The systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies found in a search in three different databases (Web of Science, Scopus, and PsycINFO) provided findings on cybervictimization, which studies to date had only identified as consequences associated with this phenomenon in all environments (Brown et al., 2014). Therefore, the objective this study pursued was to find out the effect of the relation between cybervictimization with anxiety and depression disorders in an adolescent population, since some studies have shown the negative consequences to victims of cyberbullying (Bauman et al., 2013; Brown et al., 2014). Adolescent victims of cyberbullying have a high risk of psychological distress through negative emotions and feelings of guilt (Rey et al., 2020) and, moreover, these situations generate feelings of helplessness and desperation because they cannot intervene (Dong, 2020).

The results of this meta-analysis, showed that adolescent victims of cyberbullying have a greater likelihood of anxiety and depression (Martínez-Monteagudo et al., 2020), as both disorders are predictors of cybervictimization (Marciano et al., 2020). In addition, their stage of development is also a predictor of this type of phenomenon (Audrin & Blaya, 2020; Martínez-Monteagudo et al., 2020).

The relationship to cybervictimization with anxiety had significant (when the confidence interval has no zero, indicating the effect size was significant), positive, and medium magnitude (r ≈ .30), a mean effect size of r = .31 (CI of 95% = .20 to .42), and with depression of r = .28 (CI of 95% = .19 a .36), explaining 9.6% and 7.8% of the variance, respectively. There did not seem to be any impact of publication bias in the studies selected, and the rest of the tests done demonstrated the total reliability of the effect size. These results are in line with other studies which show high levels of anxiety and depression disorders in adolescent victims of cyberbullying (Audrín & Blaya, 2020; Jenaro et al., 2017).

Our results suggest that the moderately strong relationship between cybervictimization and depression and anxiety would benefit from a larger number of more detailed studies of the association between these two disorders and the factors that moderate their relationship with cybervictimization. The results of the meta-regression analysis showed that the mean age and percentage of females are influential covariates in the relationship between cybervictimization and anxiety. In turn, these two moderators, along with the place where the study was done, are influential factors in the association of cybervictimization and the depression disorder. However, more research analyzing the effect of these covariates on the relationship between cybervictimization and these two disorders would still be necessary in view of the few studies analyzed.

As in any study, this meta-analysis also had some limitations that should be taken into account. In the first place, the number of studies selected is not very large, and so it would be a good idea to widen the search to other databases to be able to check the effects and the confidence interval. In the second place, the selection of studies only considered those in English and Spanish, which could be considered a bias in the study selection. Nonetheless, we believe that this did not affect the results, as English is the language most used in scientific literature. In the third place, there was diversity in gender and nationality, but not in age, as the age range of the sample was restricted to adolescents.

Future studies should widen the search to other databases and selection criteria. A comparison by gender could be made, as well as a study of other moderators between cybervictimization and the two disorders, such as gender and educational stage or educational level of the participants. We could also analyze whether this relationship also exists between the rest of the agents involved in cyberbullying, and whether it also occurs at other levels of education, such as primary and university, where the prevalence of cyberbullying is lower.

Conclusions

The results of this study, in spite of the limitations, show a statistically significant relationship between cybervictimization and depression and anxiety disorders. That is, the poor management of use of the new information and communication technologies may lead to psychological and social maladjustment of individuals with negative repercussions on their development.

Given the relationship of this phenomenon with both disorders, the importance of creating and implementing prevention and intervention programs is evident. Such programs should take into consideration the attitudes and behaviors acting as risk factors of cybervictimization, which can lead to psychological, behavioral, and educational problems, as well as protective factors that could help palliate such adverse situations.

Therefore, the findings show a series of practical implications for health and education that must be considered in the study and design of future interventions. Throughout this study, the relationship between anxiety and depression of adolescent victims of cyberbullying has been demonstrated. This could be behind the significant increase in mental health problems, and therefore, intervention in both those aspects would have a positive impact on adolescent wellbeing.