BRAZILIAN NATIONAL HEALTH SYSTEM

Brazil is the fifth largest country in the world covering 47% of South America, with an area of 8.5 million square kilometers and is divided into five administrative regions.1 Brazil has an estimated population of 212.5 million people in 2020 with 88% of Brazilians living in urban areas. Population growth is decreasing as the fertility rate is reducing to only 1.7 live births per woman in 2020, compared to 6.1 in 1955. Brazil ranks 75th globally in life expectancy at 76.6 years of age. Low life expectancy for males is related to "deaths for external causes" among teenagers and young adults.2 Brazil ranks 28th infant mortality rate with 11.0 infant deaths per 1,000 live births and ranks 24th in deaths of children under 5 years old: 13.0 per 1,000 live births.3 Similarly to other countries, the country suffers from a high burden of non-communicable diseases, accounting for 91% of deaths. In 2019, the main causes of death were circulatory diseases (26.8%), cancer (17.4%), respiratory diseases (12.0%), and external causes (10.5%).

The Brazilian National Health System (BR-NHS) has a large public health system with universal healthcare coverage. The organization and development of the healthcare system is a relatively recent, starting in 1990.3,4 The BR-NHS was created through the Federal Constitution and the Federal Law 8080/1990.5 The system is based on the principles of universality, equity, and comprehensiveness for health care. The system aims to provide all the population with access to high-quality health services in any place and for any health condition (Table 1).6,7 Approximately 54% of health expenditure occur in the private sector, which serves only 25% of the population. Thus, the majority of the poor have difficulty accessing health care, although it is free and universal, reinforcing inequity in access to health care.8-11

Table 1. Brazilian National Health System organization.6

| Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principles and premises | Coverage and eligibility/entitlement | Automatic universal coverage system for all citizens. Since the BR-NHS covers all Brazilians, choosing to pay for a health insurance is an individual decision that implies double the possibility of access (public and private) to the health network. It generally aims to improve the available network or reducing the time for access to health care. | ||

| Role of the state | Social welfare. Responsible for the funding, management and delivery of health services | |||

| Emphasis of reforms | Subsidy of supply to guarantee equitable access | |||

| Funding | Publicly funded via tax revenues (general taxes and contributions for social insurance) the federal, state and cities government have distinct rules in funding and provide medicines and care. See Table 4 ‘Peoples Pharmacy of Brazil', ‘Basic Component', ‘Specialized Component' and ‘Strategic Component' for detailed information. | |||

| Efficiency of system | Lower operating and administrative costs. Reduced unit costs due to economies of scale. Lower total expenses due to greater regulation of supply. | |||

| Design of service system | Networked, territorialized, PHC-orientated services | |||

| PHC approach | Comprehensive | |||

| Service provision | Services are provided mainly by the public sector, but sometimes public services, especially hospital services and diagnostic services, are delivered by the private sector through public-private partnership. | |||

| Integrality and package of services | Integration between individual care and public health actions. Integration of health promotion, prevention and care. Comprehensive care is implicit offering a broad spectrum of health services free of charge, including: preventive services, immunizations, primary health care services, outpatient specialty care, hospital care, maternity care, mental health services, medicines supply, physical therapy, dental care, optometry and other vision care, durable medical equipment (including wheelchairs), hearing aids, home care, organ transplant, oncology services, renal dialysis, blood therapy and any other necessary care. | |||

| Social determinants of health (SDH) | Incorporates the SDH approach. Facilitated possibility of intersectoral action | |||

| Equity | Guaranteed access to, and use of, health services between social groups for equal needs, regardless of ability to pay. | |||

| Co-payments/coinsurance and safety nets | Service type | Public sector | Private insurance fees per encounter/service | Maximum annual out-of pocket costs and safety nets |

| PHC visit | No charge | No limit and no limit with co-payment depending of insurance type | No limit | |

| Specialist consultation | No charge | No limit and no limit with co-payment depending of insurance type | No limit | |

| Hospitalization | No charge | No limit and no limit with co-payment depending of insurance type | No limit | |

| Prescription drugs supply | No charge, except for ‘Peoples Pharmacy of Brazil 10% of medicines costs | Not covered | - | |

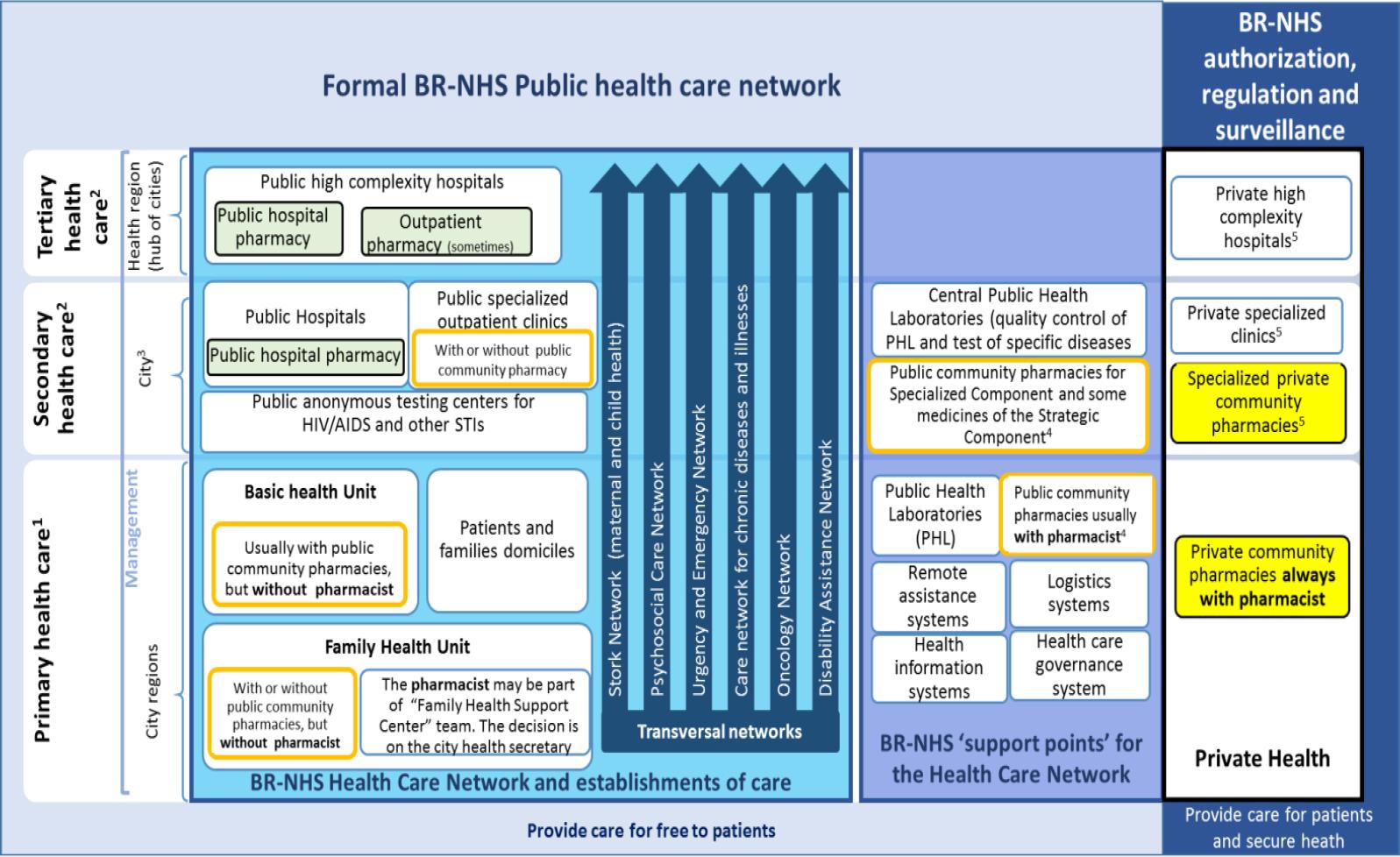

The health system is divided into public and private however private providers do provide services to the public sector with government remuneration and at no cost to the patient (see Figure 1). The private sector is authorized, regulated, and supervised by the BR-NHS with similar rules to those for the public sector.8,11-14

Figure 1. Rule of Public and private community pharmacies in BR-NHS 1At the federal government level linked to the Secretariat of Primary Health Care. 2At the federal government level linked to the Secretariat of Specialized Health Care. 3Small cities usually use hospitals and secondary health care of the hub of cities. 4At the level of the federal government linked Secretariat for Science, Technology, and Strategic Inputs - Pharmaceutical Management Department. 5These establishments can provide care for free by the partnership with BR-NHS. In this case, the services are named as procedures performed on an accredited public network and they are free for patients.

Public community pharmacies exist both in isolated location and as part of a multiprofessional health center. When in isolated locations, public community pharmacies are more likely to have a pharmacist (for 8 hours on working days). However, in most cases, these pharmacists are not formally considered as part of the multiprofessional care team, and they have access only to the patients' prescriptions, and cannot consult or write in the patients' medical records. Public community pharmacies located at healthcare centers, are often under the supervision of a health professional who is not a pharmacist (usually a nurse), and frequently have no pharmacist in charge. However, pharmacists, when they are part of that pharmacy staff, are generally considered part of the multiprofessional care team with access to consult and annotate the patients' medical (Table 2).7, 9-11,13-15

Table 2. Characteristics of public and private pharmacies in relation to insertion in the BR-NHS

| Public community pharmacy (isolated or as part of other health service) | Private community pharmacies | |

|---|---|---|

| • The only room that usually holds 7 days of medicines stock, one or more computers for supply management and dispensing control, and a place to store documents | • Ample space with access to over-the-counter products, counter with separation for controlled-sale products. Often, room for injection and dressing. Occasionally, private space for patient care. | |

| • The contact with the patient, which often generates in queues, is made through a window | ||

| • Patient access to the internal environment of the pharmacy, in most cases is prohibited | • The patient has access to most environments | |

| • They generally do not have specific locations for the pharmacist to talk to the patient. Mainly in isolated community pharmacies. When inserted in a health service, it is possible to use multiprofessional offices to provide other pharmaceutical services. | • Occasionally there is a private space for patient care, but generally, the room for injection and dressing is used to communicate with the patient in some privacy. | |

| Isolated public community pharmacy | Public community pharmacy as a multiprofessional service sector | Private community pharmacies |

| Pros | ||

| Classified as a health service | Part of an HCN service | Most common type of healthcare facility in the country. |

| There is more likely to be a pharmacist at the pharmacy. However, it is still very common for isolated public pharmacies to work without a pharmacist | Sometimes the number of pharmacists in the public network is higher because there are those linked to the central or central administration of medication supply and also those specific to direct patient care. This is a decision of the city's Health Secretary, so it varies greatly depending on the city and over time in the same city according to the group chosen. | Always have at least one pharmacist for 8 hours during working days. Sometimes, there are pharmacists at all hours of operation that can be up to 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. |

| Reduction in the number of pharmacies in the city (less structure to control and financing) | When there is a pharmacist at the pharmacy: • Typically, as fewer patients are connected to the service and the distribution of catches by the patient/pharmacist is better • The pharmacist is considered part of the multiprofessional team or part of the support team of the basic team. So it's easier to communicate with the rest of the healthcare team • Often, access to and registration in the patient's medical record |

Inspection of professional practice and compliance with health requirements are more intense |

| Lower complexity in medicines management processes between the city's central medicines supply centre and community pharmacies (usually 7 or 15 days of supply) | Increase in the number of pharmacies in the city (more opportunities for patients' access). In general, patients live close to pharmacies, which facilitates the relationship with them | |

| Cons | ||

| Service of secondary importance in the health system that almost always serves several health care units | Usually, the person in charge of the pharmacy is a health professional other than the pharmacist, often the nurse | The property generally belongs to non-professionals who sometimes interfere with the pharmacists' technical conduct. |

| The greater number of patients linked to the service does not guarantee proportionality in relation to the number of pharmacists or assistants | Occasionally, the number of pharmacists in the public network is lower and they are usually linked to the central administration or Central Supply | They are not considered part of the health care system |

| Patients need to travel long distances to get their medicines or to access pharmaceutical services (this can be a problem for those in need or work) | Increase in complexity in the management of drug distribution processes between supply centres and pharmacies | The health system does not have information about the services provided in these pharmacies and vice versa |

| The pharmacist is generally not considered as a part of the patient's health care team and has difficulty communicating with other health professionals | There is no national patient information system or electronic medical record system that communicates prescribers to private community pharmacies. Thus, private pharmacies only access patients' prescriptions and it is sometimes difficult to prevent fraud. | |

| Pharmacist often accesses only the patient's prescription and is unable to document the care provided in the patient's medical record | Pharmacists find it difficult to communicate with prescribers | |

While private community pharmacies can sell any medicine, public pharmacies dispense free of charge only medicines funded by the BR-NHS. Private community pharmacies are the most accessible healthcare setting in the country, however the information about their activities that they provide to municipal, state and federal governments, is limited to the dispensing data of the special controlled medications.8,12

PUBLIC AND PRIVATE COMMUNITY PHARMACIES' ORGANIZATION

Public community pharmacies are usually a small room to accommodate 7-day stock supply as well as administrative documents. Generally, public community pharmacies do not have specific locations to perform patient consultations with privacy, but in pharmacies located in healthcare centers pharmacists can use rooms shared with other professionals to ensure privacy. These pharmacies are open 8 hours on business days, sometimes without pharmacist on duty (Table 2).

Private community pharmacies generally have ample space to enable patients' access to over-the-counter products (self-selection and picking) and counters to dispense prescription medicines. Often, these pharmacies have a room to inject. Occasionally, private pharmacies have a small room to ensure privacy, but very frequently, the injection room is used for these purposes. These pharmacies work 24 hours a day, seven days a week, but they sometimes have a pharmacist only 8 hours in weekdays (Table 2). No restrictive legislation about private pharmacies location or establishment exists, resulting in a concentration of pharmacies in city centers, while low socio-economic areas and rural have insufficient number of pharmacies. In January 2019, 114,352 pharmacies were registered in the BR-NHS, with 77% private community pharmacies and with the distribution throughout the country showing different density patterns relative to the population (Table 3).

Table 3. Brazil and administrative regions characteristics, primary health care system production in 2019 (public community pharmacies) and insertion of Private Community Pharmacy on it

| Information | Brazil | Region | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | Northeast | Southeast | South | Midwest | ||

| Area (km2) | 8,515,767 | 3,853,676 | 1,554,291 | 924,620 | 576,774 | 1,606,403 |

| Number of states and | - | 7 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Population | 18,430,980 | 57,071,654 | 88,371,433 | 29,975,984 | 16,297,074 | |

| Private community pharmacies3 | ||||||

| Number | 87,794 | 6,628 | 21,047 | 37,432 | 14,038 | 8,649 |

| Per capita (per 10,000 inhabitants) | 4.18 | 3.60 | 3.69 | 4.24 | 4.68 | 5.31 |

| Pharmacist number3 | ||||||

| Number | 221,258 | 13,416 | 33,290 | 109,614 | 42,719 | 22,219 |

| Per capita (per 10,000 inhabitants) | 1.05 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 1.24 | 1.43 | 1.36 |

| Pharmacist annual salary in EUR; Mean (SD)1 | 5,502 (1,218) | 4,468 (854) | 5,112 (987) | 6,478 (280) | 6,548 (400) | 6,430 (1,223) |

| PHC prodution1,4 | ||||||

| Number of approved procedures | 3,759,673,839 | 223,953,823 | 769,923,437 | 1,896,133,871 | 597,869,433 | 271,793,275 |

| Medicines | ||||||

| Number | 1,022,200,782 | 17,428,199 | 160,784,629 | 578,919,758 | 196,878,845 | 68,189,351 |

| Proporcion (%) | 27.2 | 7.8 | 20.9 | 30.5 | 32.9 | 25.1 |

| Approved value in EUR1 | 3,526,039,529 | 133,044,871 | 509,987,847 | 966,481,763 | 385,194,150 | 144,875,161 |

| Medicines3 2 | ||||||

| Value in EUR1 | 80,216,968 | 2,502,368 | 10,627,608 | 45,377,439 | 14,408,889 | 7,300,663 |

| Proportion (%) | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 4.7 | 3.7 | 5.0 |

| Federal complement value in EUR1 | 7,489,716 | 103,907 | 720,597 | 4,134,341 | 2,416,514 | 114,354 |

| Federal complement (%) | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0.05 |

1One euro was 6.07 BRL, 2 Datasus information10,11,58,

CFF information54 Dispensing at public community pharmacies only

ROLE OF PHARMACIST AND OF PUBLIC AND PRIVATE PHARMACIES IN THE PROVISION OF HEALTH SERVICES

Federal Law 5,991 of 1973, known as the "Pharmaceutical Trade Law" regulates prescribing rights, pharmaceutical trade, pharmacist activities, and the types of establishments authorized to market medicines and health-related products.16 Pharmaceutical services by public and private community pharmacies, other than dispensing of medicines are not contemplated in this law.16-19

After significant efforts by the Brazilian Federal Pharmacist Association (CFF) [Conselho Federal de Farmácia] promoting the role of public and private community pharmacies and pharmacists as health services providers and active participants in health care networks (HCN) at PHC, in 2014 the Law 13.021 was enacted.20-25 This law, known as the ‘Pharmacy Law', described pharmacies as service delivery centers. Services such as vaccination, already regulated within the scope of professional duties by the CFF, and others such as functional foods and Cannabis products are now being dispensing by specially accredited private community pharmacies after being approved by regulators.26-30 An important number of pharmacists, who felt comfortable providing only dispensing services, lobbied against the implementation of this law.31 Therefore, these regulations are far to be applied in practice.32

Public community pharmacies

Since pharmacies main role is around the supply of medicines and other health products, governments and society expect that pharmacists and public and private community pharmacies provide quality medicines in a timely manner to all citizens. A Government document covering the supply/delivery of medications solely covers administrative issues, type of medications and the financial processes associated with this supply (Table 4).33-36 These are divided into:

Table 4. Federally funded pharmacy schemes in Brazil

| Information | Private pharmacies | Public pharmacies | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategic Component | Specialized Component | Basic Component | Peoples Pharmacy of Brazil | |

| Setting | Public community pharmacies | Public community pharmacies | Public community pharmacies | Private Community Pharmacy |

| Medicines or conditions covered | Medicines for tuberculosis, leprosy, malaria, leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, cholera, schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, filariasis, meningitis, trachoma, systemic mycoses, and other diseases arising and perpetuating poverty. Medicines for influenza, hematological diseases, smoking, and nutritional deficiencies are also guaranteed, in addition to vaccines, serums, and immunoglobulins. | • Medicines and other products from the cities' Essential Medicines List, especially items in Appendice III of Brazilian Essential Medicines List2Medicines and other products from the cities' Essential Medicines List, especially items in Appendice III of Brazilian Essential Medicines List2 | • Medicines and other products from the cities' Essential Medicines List, especially items in Appendices I and IV of Brazilian Essential Medicines List2 | Antihypertensive, antidiabetic, anti-asthma, and some othersAntihypertensive, antidiabetic, anti-asthma, and some others |

| • Up to 15% of the value transferred by the states and by the cities can be used to adapt the physical space of BR-NHS community pharmacies2. | ||||

| Aim | Equitable access to medicines and supplies, for the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and control of diseases and conditions of the endemic profile, with epidemiological importance, socioeconomic impact or affecting vulnerable populations, contemplated in BR-NHS strategic health programs. | Guarantee of comprehensive treatment for all clinical conditions contemplated in the different lines of care defined in the ‚Brazilian Clinical Protocols and Therapeutic Guidelines‛ | Assistance to the most prevalent diseases and conditions | Atenolol, captopril, propranolol, losartan, metformin, glibenclamide, human insulin NPH, human insulin regular, ipratropium bromide, beclomethasone dipropionate, salbutamol sulfate |

| Funding1 | Federal | Group 1: financing is under the exclusive responsibility of the Union | Fix amount of money per capita/year invested by the cities (€ 0.39), state (€ 0.39) and federal government (very low MHDI: € 0.99; low MHDI: € 0.98; average MHDI: € 0.98; high MHDI: € 0.97; and very high MHDI: € 0.96). | Subsidizes the most prevalent therapies |

| Group 2 e 3: medicines under the responsibility of the Health Departments of the States and the Federal District | ||||

| Supply | Medicines and supplies are financed and purchased by the BR-NHS | Group 1A: centralized BR-NHS acquisition | Cities, except the acquisition and distribution of human NPH and regular human insulins; clindamycin 300 mg and rifampicin 300 mg exclusively for the treatment of moderate suppurative hidradenitis and medications and supplies for female contraception that are done by the federal government | Each private community pharmacy |

| Group 1B: acquired by the States with the transfer of financial resources from the BR-NHS as reimbursement | Filling up prescriptions requires a patient visit to the pharmacy, holding an official picture ID containing the social security number, and the signed prescription. Full information of the clinic, hospital, or health unit must be informed in the prescription. In cases the patient cannot go in person to the accredited pharmacy, a registered letter of attorney will do. The medicines must be prescribed by its reference/ brand name or according to the Brazilian Common Denomination of drugs. | |||

| Dispensation | States and the Federal District. It is up to these to receive, store and distribute to the cities | States and Federal District Health Departments | Cities | |

| Regulation | 5858 | 37,57 | 37 | 34 |

"Basic Component", which meets the demands of ‘Essential Medicines' for primary health care.

"Strategic Component" which provides funds for the treatment of neglected diseases such as leprosy, tuberculosis, malaria, AIDS, and coagulopathies,

"Specialized Component", which involves the high-cost and high-complexity medicines that are dispensed only following their specific National Clinical Protocols and Therapeutic Guidelines.

Although BR-NHS guidelines mentioned the provision of services as a function of community pharmacists, in the "Portfolio of Primary Health Care Services" no billing codes for clinical pharmacist service are described.37 Interestingly and reflecting the government's expectation for public community pharmacies performance indicators in Primary Health Care (PHC) are limited to medicines supply (Table 3). No information relating to clinical services was included.38,39

A few public pharmacies initiated some clinical services, such as screenings, health education, management of minor illness, medication reconciliation, or medication review.40 Government funding for pilot projects aiming the implementation of pharmaceutical services was obtained. The state of Minas Gerais initiated in 2008 the pilot of the Pharmacy Program of Minas [Programa Farmácia de Minas] including 67 cities of up to 10,000 inhabitants and involving pharmacies that serve any component (i.e., basic, specialized and strategic). The objective was to improve the quality of drug dispensing services, as well as to promote the provision of clinical pharmacist services and provided funds to improve in the physical structure of pharmacies, training, and pharmacists' remuneration.41 This pilot was successful and is still active as a state government program, serving a large number of cities, now with different population sizes. The economic viability assessment of the "Pharmacia de Minas Program" demonstrated it be to be a useful model of public health service, in line with the BR-NHS principles to guarantee complete and universal health services to citizens.42 Recently a prospective observational study was published comparing the results with psoriatic arthritis patients of these pharmacies with others Brazilian public community pharmacies. The medication adherence, medication persistence, and clinical outcomes were evaluated at 12 months of follow-up. The results showed for the 197 patients included in the study had medication adherence of 74.6% and persistence of 72.1%. The medication persistence of patients attended by this program was higher than the overall patients in Brazil, which indicates the importance of pharmaceutical services to provide health care and promote the effectiveness and safety of biological therapies.43

The first major pilot with federal government funding took place in Paraná state, starting in 2012. This project produced four publications reporting the general characteristics and the process indicators, but without publishing results of the impact on health outcomes.44-47 In this project, pharmacists interviewed patients at the ambulatory care department of the main public hospital in Curitiba to improve their knowledge about medication and to identify potential drug-related problems, by using a long structured interview guide. With the completion of the pilot in Curitiba, capital city of Paraná, resources were deployed to train and develop the structure for the consolidation of these services, but no further information nor publications exists. The Paraná pilot project was reproduced, with a slightly different methodology in two other cities; but the publication of the results has not yet been completed.

In 2019, the Pharmacy Department of Paraná State government initiated a large-scale pharmacists' service implementation plan focused on the Specialized Component (high-cost and high complexity medicines). This program aims to merge the technological resources, mainly IT, and the district pharmacy team human resources to create a series of data-driven pharmacist services, e.g., new medicines service, medication review, medication follow-up, intensive pharmacovigilance.48 As a first output of the project, coverage of rheumatoid arthritis treatment has been demonstrated to be inadequate, requiring additional state funding.49 District pharmacists were also responsible for the patient education and the logistic control of original-to-biosimilar switch in rheumatoid arthritis biological treatments, ensuring the compliance with international safety recommendations and avoiding medication wastage.50

The CFF published a report to encourage the dissemination of good pharmacist practices in the BR-NHS. In 2019, a total of 13 "Successful experiences in the BR-NHS" [Experiências exitosas no SUS] implemented by public pharmacies were identified.51 The main problem of these experiences is that they were isolated initiatives without a systematic common support or methodologies. There are prospects for strengthening integration of pharmacists in the patient care team, which has been stimulated by the recent institutional and regulatory transformations, not fully implemented yet.36

Private community pharmacies

The relationship of private community pharmacies with BR-NHS is limited to dispensing a limited list of medicines through a program called ‘Peoples Pharmacy of Brazil' [Farmácia Popular do Brasil]. In this program, medicines for hypertension, diabetes, asthma are dispensed, to any patient with a prescription, with the government reimbursing covering 90% of the medicine price. Although the Peoples Pharmacy Program is available across the country, problems of access to medicines after commercial business hours still exist.52 The rationale of this program was based on a study performed in 2013, that reported that the proportion of people who received at least one of the prescribed medicines in the public health service was only 33.2%. The study showed that, on average, 40% of the drugs prescribed in primary care were not available when they were needed in public pharmacies.53

Brazil does not have a fully implemented national system that compiled data about prescriptions, dispensing or other pharmaceutical services from private community pharmacies, other than the Peoples Pharmacy Program dispensing. This means that information about the services is unknown to the government or civil society.

In 2019, the largest private community pharmacy chain, with more than 80,000 private community pharmacies reported that 2,978 pharmacies of their pharmacies had private consultation rooms used to provide clinical care. More than 3 million consultations have been carried out by 7,789 clinical pharmacists with a 39% increase rate in the past two years. The most frequent pharmaceutical services performed were clinical assessment of patients and point-of-care tests (41.15%), followed by injectable medication administration (26.83%). Young adults seek services to help them with weight control more often and children seek services for vaccination.28 No data about the out-of-pocket cost of these services or the overall amount of revenue obtained with these services have been published.

Health workforce and pharmacists

All the healthcare professionals in Brazil once completing their university degrees are considered able to practice after registering within the CFF. After the first registration, no re-register or re-certification processes are required to maintain the practice.54 Pharmacy is the third-largest health workforce with 42,243 pharmacists registered on BR-NHS as pharmacists (including pathologists).7 These pharmacists worked in 101,478 different settings mostly in public or private pharmacies (89.1%).55 The Pharmacists are in the 16th position in the national salary ranking and the 2nd for health professionals. the Brazilian per capita annual salary is about EUR2,700, with large differences among the five Brazilian regions (Table 3).

Pharmacy technicians do not officially exist in Brazil.56 All actions performed by pharmacy auxiliary staff are under the responsibility of the pharmacist responsible for that pharmacy. A movement to establish an allied degree in pharmacy exists after recognizing that technicians are an important part of the pharmacy workforce and their skills are needed to assist the pharmacist.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Despite the many attempts to expand clinical pharmacy services, it is worrying that the public and private community pharmacies are not considered part of HCNs of the BR-NHS. Also, governments only expect from pharmacies the supply of medicines to the population.

A joint effort from CFF, Universities and pharmacy departments of State governments should be done to improve clinical pharmacy education, to obtain more funds to support pharmacy practice research, and to improve regulations that facilitate the implementation of clinical pharmacy services in Brazil.

Finally, work has to be done to convince stakeholders about the need for the reorganization of the BR-NHS to review the conceptual framework of the organization of "Health Care Networks", including community pharmacies in a more prevalent position than just as network supporter.12,15