INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is considered a chronic disease, characterized by the presence of high glycemic concentrations, causing disturbances in lipid, carbohydrate and protein metabolism, which in turn are caused by the absence or deficiency of insulin secretion by pancreatic β-cells in pancreatic Langerhans islets (1). The hyperglycemia caused by diabetes may be controlled by exogenous insulin and other medicines. Yet, despite therapy, renal, vascular, ocular, skin, and peripheral nerve complications are common occurrences that reduce life span and quality for these patients (2).

Besides hyperglycemia, other symptoms, including dyslipidemia or hyperlipidemia, are involved in the development of the micro and macrovascular complications of diabetes, being the primary causes of diabetes-related morbidity and mortality (3). Diabetic nephropathy, a pathologic process secondary to microvascular damage, is the most common cause of terminal chronic kidney failure (TCKF) in patients under dialysis treatment in developed countries (30 % of all cases) and Latin American countries (20 % of all cases) (4). The presence of uremia and creatinemia in clinical lab examinations is an important marker for the evaluation of renal damage as caused by DM. The metabolization and excretion of urea, which results from proteolysis, as well as creatinine elimination as carried out by the urinary system, are jeopardized by the renal damage caused by hyperglycemia, which leads to the accumulation of these toxic metabolites within the organism (5).

The diabetic syndrome and oxidative damage are strongly interrelated. Diabetic hyperglycemia promotes the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), generated by reduction of one or two electrons from the oxygen molecule (O2) (6,7). The cell damage caused by these free radicals may be irreversible, as they chronically accumulate in the body tissues. In this context, guarana (Paullinia cupana) has been described as an antioxidant agent possessing bioactive compounds that act directly on the body's metabolism, including methylxanthines, caffeine (8), theobromine (9,10), theophylline, tannins, saponins, catechins, epicatechins, and proantocianides (10 11 12-13). Caffeine is the main methylxanthine present in guarana extract (14), while polyphenols such as epicatechins and catechins are present in smaller concentrations, possessing a high biologic potential (15,16). Among the beneficial effects of polyphenols are the neutralizing effects of reactive oxygen species such as the superoxid anion and the hydroxyl radical, enzymatic activity, inhibition of cell proliferation, and antibiotic and anti-inflammatory effects (17,18). Saponins and tannins are found in high concentrations in guarana. These compounds, besides protecting DNA from damage (19), exert their antioxidant actions through inhibition of lipoperoxidation (20 21-22).

Due to the potential risk of clinical and metabolic disturbances related to the increase in oxidative stress caused by diabetes mellitus, and considering the antioxidant action of guarana, this study aims to evaluate the possible protective action of this compound on the biochemical profile of alloxan-induced diabetes in rats.

METHODS AND EXPERIMENTS

ANIMALS

The use of animals in this study was approved by the Ethics Committee for the Use of Animals at Universidade Federal Fluminense (CEUA–UFF), under approval number 972. Twenty-eight young male Wistar Furth rats (55 days of age) were enrolled for the experiment. These animals were randomly divided into 4 experimental groups as follows: the control group (CG) was fed a standard diet; the guarana group (GG) was fed a standard diet supplemented with guarana; the diabetic group (DG) included alloxan-induced diabetic rats that were fed a standard diet; and the diabetic guarana group (DGG) included alloxan-induced diabetic rats that were fed a standard diet supplemented with guarana.

All animals were provided by the Nucleo de Animais de Laboratório (NAL/UFF) and placed in individual plastic cages at a temperature of 21-23 ºC with a relative humidity of 60 %, light and darkness cycle control (12/12 h), and free consumption of water.

ALLOXAN-INDUCED DIABETES

The induction process was initiated with a feeding restriction over 30 hours in which the animals did not receive any kind of feeding except free water consumption. After the fasting period, the animals were manually contained and administered an intraperitoneal injection of alloxan monohydrate 98 % (Cayman Chemical, code 9002196) previously diluted in a 0.9 % sodium chloride solution in the proportion of 600 mg of alloxan in 40 mL of saline solution. This 1.5 % solution was administered at a dose of 1 mL for every 100 grams of live weight through a 25 x 7 needle on the right inferior quadrant of the abdomen, with the animal duly contained. The rats were then put back in their cages with water and commercial rat feed ad libitum (23).

The glycemia of all rats was measured three days after the administration of alloxan; following a fasting period of 6 hours, a drop of blood was obtained through a puncture with the aid of a scalpel on the animals' tail, and a OneTouch Ultra glucometer (Johnson & Johnson Company, USA) was employed to analyze the animals' glycemia. All animals presented glycemic levels equal to or higher than 270 mg/dL, hence they were considered to be diabetic and were included in the experiment (24). The animals remained under experimentation in the bioterium for a period of eight weeks, and their glycemia, food consumption, and body weight were evaluated weekly. None of the animals died during the induction of diabetes or during the experimental period. No reversion cases were observed.

EXPERIMENTAL FEEDS

The experimental feed was prepared at the Experimental Nutrition Laboratory at UFF (LabNE). A commercial pelletized feed was used (Nuvilab®, Nuvital, Paraná, Brazil) (Table I).To the experimental feed offered to the DGG and GG groups, 2 g of powdered guarana(Paullinia cupana) were added per kilogram of feed (25). The control group feed was also prepared from the same commercial pelletized feed, so that all animals received a standard diet. The ingredients were weighed and homogenized by an industrial mixer (Hobart®, São Paulo, SP, Brazil) with boiling water. The mass obtained was transformed into pellets and dried out in a ventilated oven (Fabbe-Primar® nº 171, São Paulo, SP, Brazil) at 60 ºC for 12 hours and, after identification, stored under refrigeration until its use.

EUTHANASIA OF ANIMALS AND COLLECTION OF BIOLOGICAL MATERIAL

At the end of the experimental period at the bioterium, the animals were euthanized. The animals were anesthetized with 75 mg/kg of ketamine + 10 mg/kg of xylazine, and the previously calculated dose was intraperitoneally administered.

Once the anesthesia condition was achieved, as assessed by absence of the foot reflex, the animals were subjected to bleeding by an intracardiac puncture, from which 10 mL of blood were obtained. After bleeding, an additional dose of anesthesia was given, which led to the death of the animal. The blood samples collected were placed in serological flasks with separator gel, centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 minutes. The obtained serum was stored at -20 ºC for the analysis of the biochemical profile.

BIOCHEMICAL PROFILE

To assess the lipid profile, serum triglycerides, total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL), low density lipoprotein (LDL), and very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) levels were analyzed. Renal damage markers (total proteins, albumin, urea, creatinine) and hepatic enzymes alanine-aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate-aminotransferase (AST) were also analyzed. These titrations were performed automatically using a Bioclin® analyzer (BioclinBS120, Quibasa – Química Básica Ltda., Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil) in the Experimental Nutrition Laboratory at UFF (LabNE, Niterói, Brazil).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The data were presented in the average and standard deviation form. To test the normal distribution of values, the Komolgorov- Smirnov test was employed. For the analysis of data, an ANOVA univariate test, in association with a multiple comparison test by Tukey-Kramer, was employed. Significance in all tests was established at the p < 0.05 level. The statistical analyses were made by the GraphPad Prism program in its 5.0, 2007 version (San Diego, CA, USA).

RESULTS

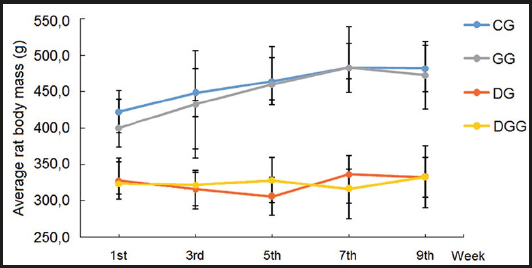

Of the 14 animals subjected to the intraperitoneal alloxan injection, 100 % developed glycemic levels above 270 mg/dL, thus being considered diabetic and included in the experiment. The mean weight of the animals was lower in the diabetic groups (DG and DGG) when compared to the control groups (CG and GG), with an extremely significant difference between groups (p < 0.0001). The results are expressed in figure 1). Consumption in diabetic groups was higher when compared to the control groups (Fig. 2). The concentration of LDL cholesterol in the GG was 33.27 % higher than that in the CG, 59.65 % higher than in the DG, and 43.67 % higher than in the DGG. The serum concentration of HDL cholesterol increased by 51.72 % in the DGG when compared to the CG, and by 57.59 % when compared to the GG.

The serum levels of ALT increased by 30.31 % in the CG when compared to the GG. In the DG, the concentration of ALT was 41.83 % higher than in the GG, and 29.58 % higher than that in the DGG. In relation to AST, the serum concentration in the DG was 44.55 % higher than in the CG, 36 % higher than in the GG, and 36.73 % higher than in the DGG. The CG and GG did not present a significant difference in serum urea levels when compared to each other; however, when compared to the diabetic groups, the DG presented an increase of 60.20 % when compared to the CG, and of 67.09 % when compared to the GG; the DGG presented an increase of 65.84 % when compared to the CG, and of 71.76 % when compared to the GG.

The average serum creatinine levels did not present statistically significant differences between the CG and GG; the DG presented an increase of 23.07 % as compared to the CG, and of 32.05 % in relation to the GG. Yet, the DGG presented a decrease of 21.79 % when compared to the DG and did not significantly differ from the CG. The remaining parameters of serum biochemistry did not exhibit any significant differences. The numeric data are expressed in table II.

Table II. Biochemical analysis

The letters a, b and c next to the means represent the groups that showed statistically significant differences. The index for statistical significance in the test (one-way ANOVA) was p < 0.05. LDL: low density lipoprotein; VLDL: very low density lipoprotein; HDL: high density lipoprotein; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotranferase; CG: control group; GG: guarana group; DG: diabetic group; DGG: diabetic guarana group. Results are shown as mean ± standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

The utilization of cytotoxic drugs aiming at a chemical induction of diabetes mellitus in Wistar rats for the production of experimental animal models is still largely employed (26,27). Nevertheless, the protocols utilized do not follow a single standard, presenting flaws in the establishment of the actual disease, reversion of the diabetic state, and post-induction death (26,28,29). During this work, it was observed that a 150 mg/kg dose of alloxan, at a 1.5 % concentration, preceded by a fasting for 30 hours and applied by intraperitoneal injection, caused an increase in glycemia in 100 % of the rats, and already within the first week. The animals evaluated presented a glycemia level equal to or higher than 270 mg/dL, and maintained this glycemia along the eight weeks of the experiment without any induction-related deaths during this period. Such data certify the efficacy of this method of induction of diabetes mellitus in rats.

Differently from what happens in humans, diabetic rats are resistant to alterations in their lipidic profile (30). The results obtained in this work reinforce this hypothesis because, in the animals that had diabetes mellitus induced by alloxan, total cholesterol, VLDL cholesterol, and triglycerides did not present any statistically significant differences between the groups tested. Such effect is reinforced by Cardozo et al. (31), who found similar results after evaluating the serum levels of cholesterol, triglycerides, and glucose in rats with alloxan-induced diabetes.

The addition of guarana powder to the diet may improve the lipid profile of rats, as demonstrated by Ruchel et al. (32), who in their experiment revealed that this phytochemical could reduce LDL-cholesterol levels in hypercholesterolemic rats. Caffeine and the polyphenols present in guarana, similarly to the components found in green tea or coffee, can reduce the oxidation of LDL- cholesterol. This protecting effect of guarana makes it appear as an efficient nutraceutic in the reduction of cardiometabolic diseases (33). Nevertheless, in the supplemented animals evaluated in this research, the cholesterol fraction that changed was the one bound to HDL, with DGG mice presenting a significant increase when compared to the animals in the CG and GG. Such results are similar to those that were observed by Lerco et al. (30).

In animal models, we can evaluate acute hepatic damage, and both aminotransferases (ALT and AST) represent the indicators mainly used by researchers (34). Serum elevations of ALT and AST are observed when a pathologic process causes hepatic cell damage (35). In this study, in relation to ALT, a significant decrease in its serum levels was observed in the test groups, the ones that were supplemented with guarana added to their diet (GG and DG), when compared to the non-supplemented groups (CG and DG). The diabetic animals that received guarana (DGG) also had a significant reduction in AST levels when compared to the diabetic control group. These results are in line with those of Kober et al. (36), who in their study evaluated the protective effect of guarana on hepatic damage in rats exposed to carbon tetrachloride, thus demonstrating the efficacy of guarana in the reduction of transaminases, by means of the stabilization of the hepatic cell membrane, which reduces the release of enzymes to the blood stream (35). The evaluation of the renal parameters showed a significant increase in the serum levels of urea in the animals of the diabetic groups when compared to the control groups, suggesting a possible picture of renal damage. Still, an analysis of the serum levels of creatinine in the tested groups showed that in the DGG serum creatinine was maintained near the CG value. An increase in the levels of urea in the DGG, without an increase in the levels of creatinine, may be linked to a greater protein intake in this group. According to Dalton (37), the titration of urea alone is nonspecific for a diagnosis of renal damage, since this parameter can undergo variations in its values because of the diet. In these cases, an assessment of both urea and creatinine will generate more reliable results (5).