INTRODUCTION

Esophageal cancer is one of the most common tumors among digestive system neoplasm, and its incidence rate ranks the 7th among malignant tumors in worldwide range (1). China is one of the countries with high incidence and death rate of esophageal cancer, the mortality rate ranking the 4th in global, and esophageal cancer has become one of the main diseases affecting the health of population (2).

The main treatments for esophageal cancer include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, biological therapy and immunotherapy. Until now, radical esophageal cancer resection is still the main method to treat patients with esophageal cancer. Nevertheless, the incidence of postoperative complications in esophageal cancer patients can still be as high as 10 % to 30 % (3).

Preoperative malnutrition can affect postoperative clinical outcomes and long-term survival. Studies have shown that postoperative complications occurred significantly more frequently in esophageal cancer patients with low prognostic nutritional index (4). Appropriate nutritional interventions for malnourished patients with esophageal cancer before surgery can reduce the postoperative hospitalization durations and total complication rate (5). Preoperative malnutrition in patients with esophageal cancer can be reversed with appropriate nutritional interventions (6). Therefore, it is of great clinical significance to explore simple, effective and highly targeted nutritional assessment tools for early clinical identification of preoperative malnutrition in esophageal cancer patients and formulation of reasonable individualized nutritional support.

In 2018, the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) published a new perception for the diagnosis of malnutrition based on a two-step method (7). The GLIM synthesizes the inclusion of indicators from a widely used assessment tool worldwide and presents a global consensus on the diagnosis of malnutrition by combining etiological and phenotypic indicators. After the release of the GLIM criteria, it has been supported by several national nutrition societies. Due to the complexity of malnutrition assessment, the GLIM encourages the nutrition community to do some further research to confirm the clinical significance of these criteria. Some studies have proved that the GLIM is a good nutritional assessment and prognostic indicator in cancer patients undergoing major abdominal surgery (8). Recently, Yin et al. reported that the GLIM criteria defined the highest incidence of malnutrition and seemed to be the best way to predict postoperative complications in esophageal cancer patients (9). In this study, 23.1 %, 12.2 % and 33.3 % of esophageal cancer patients were diagnosed as malnourished as defined by the Patient Generated-Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA), European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) and GLIM, respectively, which is much lower than the incidence of malnutrition (76 %) reported by Cao et al. (9,10).

The pathological types of esophageal cancer mainly include adenocarcinoma (EAC) and squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). The ESCC accounts for almost 90 % of esophageal cancer cases in China (11). A prognostic indicator may have different predictive value in ESCC patients and EAC patients, and the study by Yin et al. failed to differentiate ESCC from EAC, leaving its prognostic significance in operable ESCC largely unclear (9,12).

As a modified version of the SGA, Patient Generated-Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) is recommended as a standard tool for tumor nutritional assessment (13). Therefore, this study was conducted to evaluate the consistency between GLIM and PG-SGA in malnutrition judgment and to assess the effect of malnutrition as defined by the two methods on the clinical outcomes of patients with ESCC who underwent radical esophagectomy.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

STUDY DESIGN AND PARTICIPANTS

This was a prospective cohort study carried out at the Zhongshan Hospital, Xiamen University. All patients were aware of this research protocol and signed an informed consent form. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital, Xiamen University, and the data were consecutively collected between October 2018 and December 2019.

Inclusion criteria included: a) age 18-80 years; b) patients diagnosed with ESCC by gastroscopic biopsy pathology before surgery; c) patients who underwent elective thoracoscopic radical resection of esophageal cancer; d) patients who had undergone radiotherapy or chemotherapy before admission; e) patients who were able to communicate normally and able to complete the questionnaire independently or with the assistance of the investigator; and f) informed consent and voluntarily participation in this study.

Exclusion criteria were: a) patients with severe cachexia or severe impaired internal organ function diseases, such as cerebral infarction, heart disease, and severe lung dysfunction; b) palliative surgery; c) patients with distant metastases who could not undergo surgery; d) those who underwent tumor intervention such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy after admission; and e) relevant indicators involved in this study were missing or incomplete.

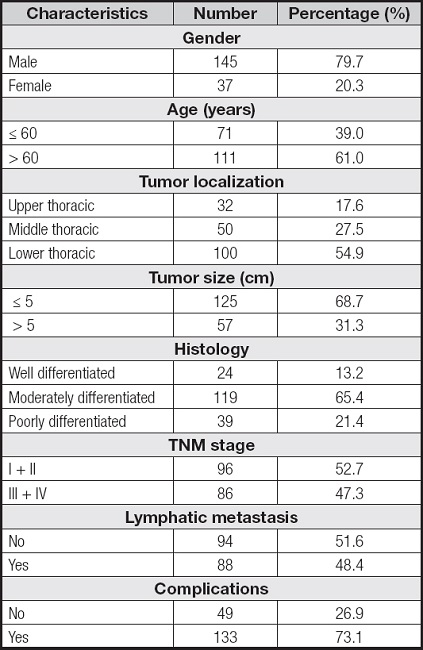

According to the above-mentioned criteria, a total of 182 patients were included, of which 145 were males and 37 were females (Table I).

DATA COLLECTION

Data were collected within 24 hours of hospitalization using standardized questionnaires, including: a) preoperative information, including age, sex, height, weight and weight changes over the past six months, body mass index (BMI), planar skeletal muscle mass index (SMI), change in food intake and preoperative nutritional support; b) tumor characteristics, including location, size, histologic type, and TNM stage; and c) clinical outcomes, including length of stay, hospitalization expenses and postoperative complications.

According to the consensus issued by the Esophagectomy Complications Consensus Group, postoperative complications can be categorized as involving the stomach, lungs, heart and so on (3). According to the Clavien-Dindo classification, postoperative complications were defined as grade II or higher adverse outcomes (14).

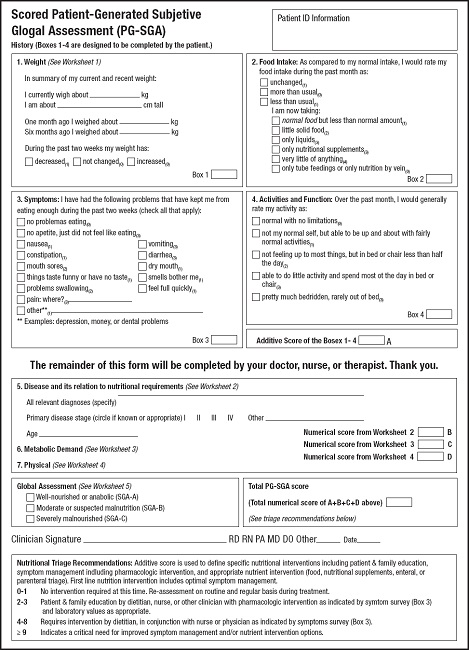

PG-SGA

PG-SGA, as a “good standard” for evaluating the nutritional status of oncology patients, is composed of two parts: patient self-assessment and medical staff evaluation. The first part mainly includes recent changes in body weight, changes in eating habits, symptoms and activities affecting eating, and limitations of activity and physical function. This part is completed through a questionnaire with the patient and the score is summed as A. The second part, which includes disease and age scores, metabolism and stress levels, and physical examination, is scored as B, C, and D, respectively, and is completed by a registered dietitian. The PG-SGA score is the sum of A, B, C and D, and the higher the score, the worse the nutritional status. After the scoring is completed, an overall evaluation is conducted, with grade A indicating good nutrition, grade B indicating moderate or suspected malnutrition, and grade C indicating severe malnutrition. For statistical convenience, grade A is classified as good nutrition group, and grades B + C are classified as malnutrition group (13) (Fig. 1).

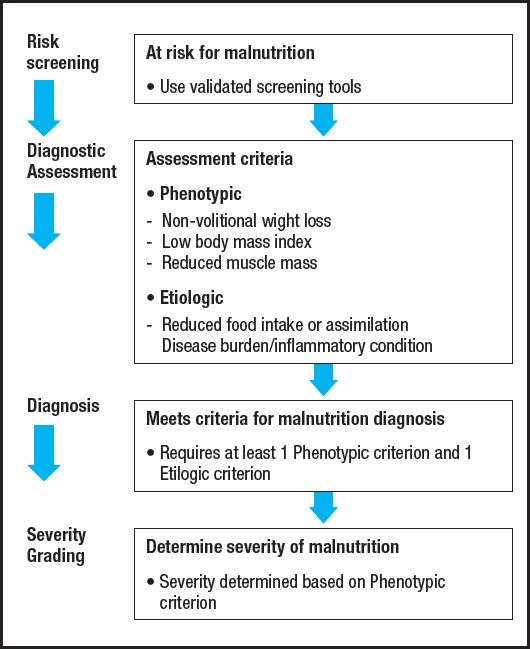

GLIM

The GLIM criteria are composed of a two-step method for the definition of malnutrition (7) (Fig. 2). The first step is to recognize nutritional status with “at-risk”, and the second step is to validate malnutrition and to assess the severity in cases of nutritional risk. In the current study, the Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS-2002) was applied for nutritional risk screening (15). Patients with NRS-2002 ≥ 3 were regarded as at risk of malnutrition.

The malnutrition assessment needs to meet at least one phenotypic criterion and one etiologic criterion. Phenotypic criteria include small BMI, non-volitional weight loss, and decreased muscle mass. Etiologic criteria include decreased food intake or absorption, and disease burden or inflammation. All included cases which were pathologically diagnosed with ESCC, which met the etiologic criteria associated with the burden of disease. For the phenotypic criteria, non-volitional weight loss was assessed according to the data of the nutritional questionnaire. Low BMI (< 18.5 if < 70 years, or < 20 if > 70 years) was defined according to the GLIM criteria on an Asian population (7). Decreased muscle mass was diagnosed based on the third lumbar vertebra (L3) cross-sectional SMI gained from abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans before operation. A threshold value (SMI < 52.4 cm2/m2 (male) or < 38.5 cm2/m2 (female) was set according to one previous study (16).

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 20.0. The continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and proportions for categorical variables. Continuous variables were analyzed using independent t-tests. Associations between the categorical variables were analyzed using Chi-squared or Fisher's exact test. The validity of GLIM was assessed using a combination of the following methods: sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV). The kappa (κ) statistic by correlation analysis was applied to assess the consistency of GLIM and PG-SGA (17). To estimate the predictive values of the malnutrition defined by PG-SGA and GLIM in the discrimination of ESCC patients with or without postoperative complications, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated. Areas under the curve values > 0.90 were regarded as noteworthy; 0.80-0.90 values, as excellent; and 0.70-0.80 values, as acceptable (18). A two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

COMPARISON OF NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT RESULTS DEFINED BY THE PG-SGA AND THE GLIM IN ESCC PATIENTS

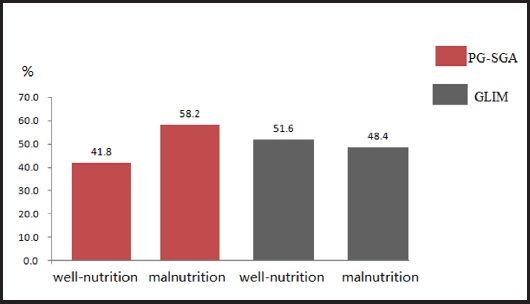

Among 182 ESCC patients, 76 patients were diagnosed with well-nourished (PG-SGA A) and 106 patients with malnourished (PG-SGA B + C) according to the PG-SGA. The incidence of malnutrition was 58.2 % and 75 patients were suspected or moderately malnourished whereas 31 were severely malnourished.

Our study results showed that 94 patients were well-nourished and 88 patients were malnourished according to GLIM. The incidence of malnutrition was 48.4 % and 55 patients were moderately malnourished whereas 33 were severely malnourished (Fig. 3).

Using PG-SGA as a reference, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of the GLIM for diagnosing malnutrition in ESCC patients were 75.5 %, 89.5 %, 90.9 % and 72.3 %, respectively. Our study results showed that GLIM and PG-SGA had good consistency in nutritional assessment of ESCC patients (k = 0.628, p < 0.001) (Table II).

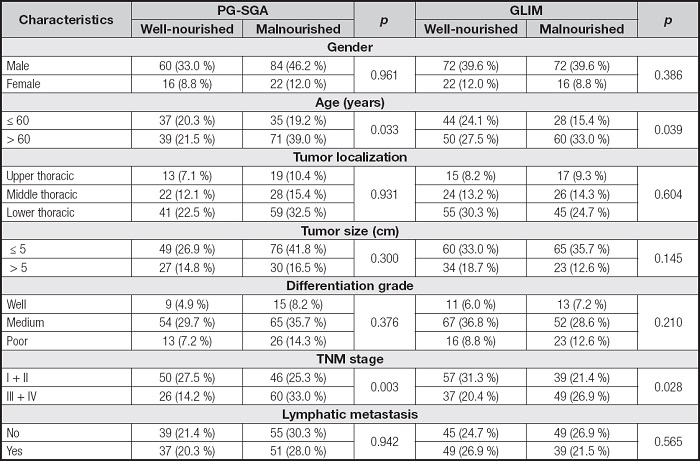

CHARACTERISTICS OF ESCC PATIENTS STRATIFIED BY THE PG-SGA AND GLIM

The associations between characteristics of ESCC patients and the nutritional status defined by the two methods are shown in table III. Of all the characteristics mentioned, the age and TNM stage were positively associated with the presence of malnutrition as defined by the two methods. There was no difference between the nutritional status of ESCC patients diagnosed using the two methods and gender, differentiation degree of tumor tissue or lymph node metastasis (p > 0.05).

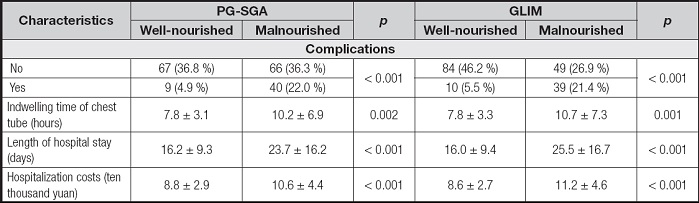

UNIVARIATE ANALYSIS OF THE POSTOPERATIVE OUTCOMES STRATIFIED BY THE PG-SGA AND GLIM

In this study, 26.9 % (49 of 182) of ESCC patients experienced pulmonary infection, anastomotic fistula and other complications after esophagectomy. The incidence of postoperative complications, the indwelling time of chest tube after esophagectomy, hospital stay and hospitalization costs of patients were positively correlated with the presence of malnutrition as defined by the PG-SGA and GLIM (Table IV).

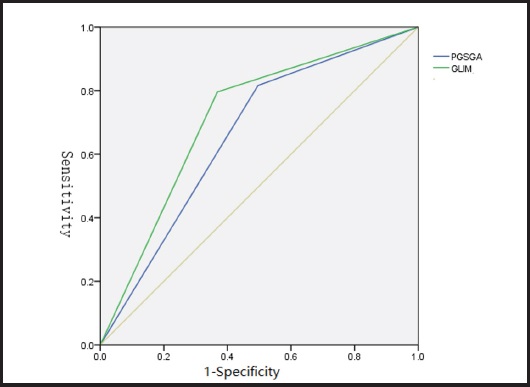

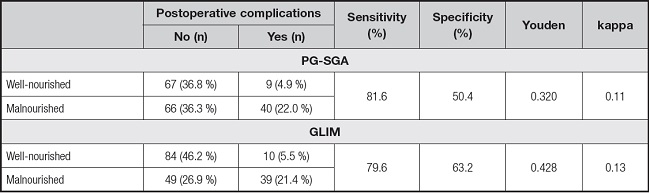

COMPARISON OF MALNUTRITION AS DEFINED BY THE TWO METHODS IN PREDICTING POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS OF ESOPHAGECTOMY

Comparing the predictive efficiency of postoperative complications, the sensitivity values of PG-SGA- and GLIM-defined malnutrition were 81.6 % and 79.6 %, the specificity values were 50.4 % and 63.2 %, the Youden indexes were 0.320 and 0.428, and the Kappa values were 0.110 and 0.130, respectively. Although the sensitivity of PG-SGA-defined malnutrition was slightly higher, the specificity and Youden index of GLIM-defined malnutrition were higher than those of PG-SGA-defined malnutrition. The areas under the ROC curve of PG-SGA- and GLIM-defined malnutrition and postoperative complications were 0.660 and 0.714, respectively. Compared with PG-SGA-defined malnutrition, GLIM-defined malnutrition had better clinical value in predicting postoperative complications (Table V and Fig. 4).

Table V. Comparison of malnutrition in predicting postoperative complications.

GLIM: Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition; PG-GSA: Patient Generated-Subjective Global Assessment..

DISCUSSION

Due to the stealth property in the early stage of the disease and not typical symptoms, esophageal cancer patients often experience a long-term body consumption before diagnosis. In the advanced stage, the esophagus is involved by the lesions, and it directly affects the patients' food intake. Patients experience swallowing difficulties, dietary changes and nutrient digestion and absorption disorders. Moreover, due to tumor growth and stress response, the body is in a high catabolic state, which aggravates the occurrence of nutritional risk (19). The results in the current study showed that 58.2 % and 48.4 % of ESCC patients were moderately or severely malnourished before surgery as defined by PG-SGA and GLIM, respectively. Similarly, Quyen et al. reported that the rate of malnutrition in esophageal cancer patients was 50.2 % with 44 % as class B (moderate malnutrition) and 6.2 % as class C (severely malnutrition) as defined by the PG-SGA (20). A recent study reported that the incidence of malnutrition in patients with esophageal cancer could reach 76 % (10). These studies showed that the incidence of malnutrition was common in patients with esophageal cancer.

According to the results reported by Yin et al., 23.1 %, 12.2 % and 33.3 % of esophageal cancer patients were diagnosed as malnourished as defined by PG-SGA, ESPEN and GLIM, respectively, which is lower than the results of the current study and other studies mentioned above. One of the reasons may lie in the recruited cases, which included both esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, while the current study only included esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Another reason may be different from the adoption of evaluation indicators. In their report, the cases for malnutrition were severe malnutrition (PG-SGA ≥ 9), while in the current study and other studies mentioned above, the cases for malnutrition were suspicious or moderate malnutrition (PG-SGA ≥ 4). Besides, a low BMI is regarded as one important indicator for defining malnutrition in GLIM, whereas BMI is not used in PG-SGA.

Malnutrition can affect postoperative clinical outcomes and long-term survival. Therefore, it is of great clinical significance to find simple, effective and highly targeted nutritional assessment tools for early clinical identification of preoperative malnutrition in esophageal cancer patients. PG-SGA remains the only validated and specific tool for a comprehensive nutritional assessment in oncology (13). It has also been suggested as the gold standard tool to evaluate the performance of other nutrition screening tools (21). Despite its significant efficacy, the need of time and trained professionals has hampered its use in many facilities and regions of the world.

After the release of GLIM criteria, the GLIM encourages the nutrition community to do some further research to confirm the clinical significance of these criteria (7). In the current study, we confirmed the validity of GLIM criteria in malnutrition judgment compared with PG-SGA and explored the effect of malnutrition as defined by the two methods on the clinical outcomes of patients with ESCC who underwent radical esophagectomy. The results of the current study showed a well agreement of GLIM with PG-SGA to identify malnutrition in ESCC patients (k = 0.628, p < 0.001). Similarly, a recent study which was carried out by Yin et al. indicated that GLIM had a diagnostic concordance against PG-SGA in patients with esophageal cancer (k = 0.519, p < 0.001). Xu et al. had already reported that GLIM criteria had a moderate agreement with PG-SGA in diagnosing malnutrition of patients with gastric cancer (k = 0.548). Thus, GLIM may have a good agreement with the PG-SGA in diagnosing malnutrition.

The results of this study also showed that there were statistical differences in patients' age, TNM stage and malnutrition as defined by GLIM and PG-SGA, respectively (p < 0.05). The incidence of malnutrition in older patients (> 60 years old) and patients with TNM stage (III + IV) was significantly higher than in patients under 60 years old and patients with TNM stage (I + II), respectively. Our findings indicate that malnutrition is prevalent in advanced and elder ESCC patients, and these patients should be paid more attention and require timely nutrition education and guidance, treatment for symptoms, such as drug interventions, and proper nutritional support.

Esophageal cancer patients with malnutrition have previously been demonstrated to have an increased risk for both postoperative complications and mortality, as compared to patients with non-malnutrition (22). In the present study, the incidence of postoperative complications in ESCC patients with malnutrition defined by PG-SGA and GLIM was significantly higher than that in patients with non-malnutrition. Reporting preoperative malnutrition as a stronger predictor of complications than good nutrition has been shown in some published studies, whereas malnutrition defined by different tools may come to different conclusions (9). Interestingly, ESCC patients with malnutrition defined by GLIM in the current study had higher complications than that in patients with non-malnutrition, the same as defined by PG-SGA. Among all the complications in the present study, the incidence of anastomotic leakage was the highest, suggesting that if these patients can be provided with appropriate nutritional intervention before surgery, the incidence of postoperative anastomotic leakage may decrease. In terms of complications and delaying hospital stay, Martineau et al. found that patients with malnutrition had significantly longer hospital stay and higher incidence of complications, which was consistent with our findings (23). In the current study, the duration of chest tube indwelling, postoperative hospital stay and hospitalization cost are significantly higher in patients with malnutrition defined by GLIM and PG-SGA than that in patients with non-malnutrition. Therefore, we believe that preoperative nutritional evaluation using PG-SGA and GLIM can effectively predict the occurrence of postoperative complications, and providing necessary nutritional support may decrease postoperative complications, shorten the length of hospital stay and reduce hospitalization costs.

Based on predicting the occurrence of postoperative complications, the sensitivity values of PG-SGA- and GLIM-defined malnutrition were 81.6 % and 79.6 %, the specificity values were 50.4 % and 63.2 %, and the Youden indexes were 0.320 and 0.428, respectively. Although the sensitivity of PG-SGA-defined malnutrition in predicting postoperative complications was slightly higher, the specificity and Youden index of GLIM-defined malnutrition were higher than those of PG-SGA-defined malnutrition. Moreover, the areas under the ROC curve of PG-SGA- and GLIM-defined malnutrition in predicting postoperative complications were 0.660 and 0.714, respectively. These results seem to indicate that GLIM-defined malnutrition has better clinical value in predicting postoperative complications than PG-SGA-defined malnutrition. One of the reasons for the difference may be that SMI is regarded as one important indicator for defining malnutrition in the GLIM, and reduced SMI at L3 is reported being closely associated with poorer clinical outcomes in cancer patients (24).

Our study design has several limitations. Firstly, the number of cases included in this study was relatively limited, and some data only reflected the trend of change to a certain extent and cannot reflect the difference well. Secondly, this study only observed and recorded the type and number of postoperative complications, but did not conduct a graded study on their severity, which needed to be further studied and expanded. Thirdly, the postoperative clinical outcomes in this study were only reflected in the incidence of postoperative complications, postoperative chest tube indwelling time, length of stay and total hospitalization cost. Follow-up analysis of long-term prognosis is still needed to better compare the relationship between different assessment tools and postoperative clinical outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows the effectiveness of malnourishment diagnosed according to the GLIM and the PG-SGA in predicting postoperative clinical outcomes among patients with ESCC. Compared with the PG-SGA, the GLIM criteria can better predict postoperative complications of ESCC. Follow-up analysis of postoperative long-term survival is needed to explore the relationship between different assessment tools and postoperative long-term clinical outcomes.