INTRODUCTION

Sedentary behavior, unlike physical inactivity, can be characterized by the performance of small movements when sitting or reclining that require an energy expenditure ≤ 1.5 metabolic equivalents (1). Epidemiological evidence supports the associations of sedentary behavior with metabolic behavior (2-4), mortality (2), and other outcomes (4) in adults. Reducing sedentary behavior could help prevent an increase in body mass index in adulthood and thereby reduce the prevalence of obesity (5), especially in college students (6).

Thus, monitoring sedentary behavior is an important step toward preventing and controlling obesity. Self-reported data (mainly collected via questionnaire) are the most frequent economically and logistically viable method of evaluating sedentary behavior in epidemiological studies (1). The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent implementation of public health measures, such as social distancing, increased remote research (7), as studies migrated from a face-to-face format to a virtual environment. However, despite the practicality of online tools, some issues may arise regarding the quality of the collected data (8), such as differences in literacy and access to the internet, especially in low- and middle-income countries (7).

Although the use of online tools can expand and increase the flexibility of questionnaire application in epidemiological studies (9,10), including health behaviors (8), an evaluation of the psychometric properties of online sedentary behavior questionnaires, especially in low- and middle-income populations, is lacking. Thus, the objective of the present study was to evaluate the reliability and validity of an online questionnaire assessing sedentary behavior in university students from low-income regions.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

STUDY DESIGN

The present cross-sectional methodological feasibility stu- dy (11) is part of a longitudinal multicenter observational study, the 24-hour Movement Behavior and Metabolic Syndrome (24 h-MESYN) study (12), and was structured according to the concepts of the scientific method (13). During the 2021 academic year, the online questionnaire was administered to participants twice to test the temporal stability of responses (reliability) and construct structural validity. Detailed information about the 24 h-MESYN study can be found elsewhere (12).

ETHICAL ASPECTS

This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki (2008 revision, Seoul, South Korea) and Resolution 466/2012 of the Brazilian Ministry of Health regarding the ethical principles of research involving humans. The study procedure was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Centro Universitário do Maranhão (UNICEUMA, no. 4055604). After the educational institution provided written consent, subjects received a formal invitation to participate in the study in a virtual environment. Subjects were also informed of the risks and discomfort of the study, in accordance with the protocols of the institution, and signed an informed consent form (ICF).

SAMPLE CHARACTERIZATION

We invited university students from a higher education institution in the municipality of Imperatriz, Maranhão, Brazil to participate in the study. In 2020, this institution had 2,225 students and offered nine majors (Nursing, Physical Therapy, Nutrition, Physical Education, Aesthetics and Cosmetics, Psychology, Social Work, Administration, and Law). To calculate the necessary sample size, we used an α of 0.05, a β of 0.10 (90 % power) and a correlation coefficient of 0.28 (14); we determined that 98 subjects were needed (15). To compensate for participant drop out (50.0 %), refusal to participate (50.0 %) and missing data (50.0 %), 342 students were invited to participate in the study. We selected students by stratified random sampling, considering distributions (60 %/40 %) based on previous studies by i) biological sex (female and male) and ii) nature of the majors (health sciences and other areas) (16,17).

ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA

We included undergraduate students ≥ 17 years of age who signed the informed consent form. We excluded students who were pregnant or had a physical disability. In the validity study, we excluded students who returned incomplete questionnaires, and in the reliability study, we excluded students who did not complete the first questionnaire. The exclusions occurred only at the time of data analysis.

STUDY VARIABLES

The operational variables of the study were (13) participant biological sex, age, major, shift of coursework, and duration of sedentary behavior.

INSTRUMENTS

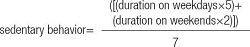

We collected data through the online questionnaire, available at https://forms.gle/L92wXsVaxxfPNgpE8. The sedentary behavior questionnaire was from the South American Youth/Child Cardiovascular and Environmental (SAYCARE) study, which was developed and validated in South American children and adolescents (18). The SAYCARE questionnaire has 10 items regarding time spent watching television, using a computer and/or cell phone, studying, playing electronic games and passive commuting on weekdays and weekends (18). The responses were reported in hours per day according to a preset scale (e.g., 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 hours per day). After administering the questionnaire, we calculated the weighted daily duration of sedentary behavior via the equation:

Additionally, we retrieved information on biological sex (male/female), chronological age (17 to 99 years), major (Nursing, Physical Therapy, Nutrition, Physical Education, Aesthetics and Cosmetics, Psychology, Social Work, Administration, or Law) and shift of coursework (morning, afternoon, evening, or full).

Procedures

To standardize the research procedures, the multidisciplinary team of researchers underwent 20 hours of training (12). During the training period, we reviewed the online questionnaire to correct typos (and issues with semantics) and address problems with the access link. Next, we conducted data collection in three stages. The first stage consisted of a direct (face-to-face) approach, in which we explained the project and sent the link to the informed consent form and questionnaire via WhatsApp. If the electronic questionnaire was not completed, we sent up to three reminders. In the second and third stages, the online questionnaire was administered twice (Q1 and Q2), separated by an interval of two weeks (12). The Q2 questionnaire was sent only to those who completed the Q1 questionnaire. In the latter two steps, our contact was restricted to messaging via WhatsApp.

DATA ANALYSIS

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata software, version 15.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). We used the Shapiro-Wilk test to assess the normality of data distribution. The significance level adopted was 95 % (p ≤ 0.05). To evaluate sensitivity, we used the chi-square goodness-of-fit test compare the distributions of the samples between Q1 and Q2 (19). To evaluate reliability, we used the Spearman correlation coefficient (a nonparametric analysis) with a cutoff point of ≥ 0.30 (20). To evaluate structural validity, we performed an exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation, excluding items with loadings < 0.3 (19). We extracted the factors based on the Kaiser rule, retaining factors with an eigenvalue > 1 (19). Previously, we conducted a preliminary analysis to determine whether an exploratory factor analysis was feasible given the data, using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test (considered feasible when KMO > 0.50) to assess sample adequacy and the Bartlett test (considered statistically significant when p < 0.05) to assess data sphericity (19).

RESULTS

Of the 342 students contacted, 43.0 % did not complete the Q1 questionnaire and 40.0 % did not complete the Q2 questionnaire. Thus, we identified a 57.0 % response rate (students contacted who completed the Q1 questionnaire) at Q1 and a 60.0 % response rate at Q2 (students who completed the Q1 questionnaire as well as the Q2 questionnaire). Detailed information regarding the sample is shown in table I. Most participants were women aged 21 to 25 years who majored in Physical Education and attended the night shift at both Q1 and Q2. We did not identify significant differences in participant characteristics at the two time points in the sensitivity analysis (Table I).

Table I. Sensitivity analysis based on sociodemographic and academic characteristics.

Q1: questionnaire first application; Q2: questionnaire second application.

*Chi-squared goodness-of-fit test.

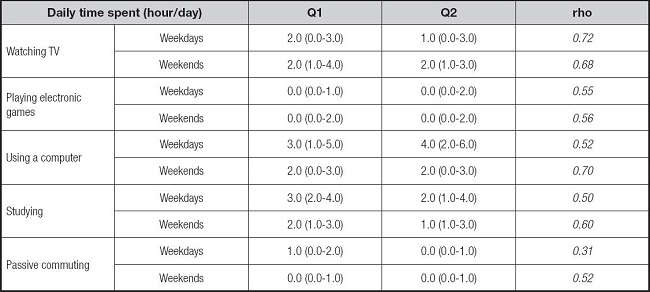

Table II shows the characteristics of sedentary behavior according to self-report data. We observed that during a typical weekday, computer use accounted for the highest median duration, followed by studying and watching TV; during a typical weekend day, watching TV and using a computer were the most common behaviors. The mean total daily sedentary duration in our sample was 9.53 (± 4.22) hours/day (data not shown). Furthermore, we identified acceptable reliability in all variables of the SAYCARE questionnaire, with Spearman's correlation coefficients ranging from 0.72 (watching TV on a weekday) to 0.31 (passive commuting on a weekday).

Table II. Reliability analysis of the American Youth/Child Cardiovascular and Environmental (SAYCARE) sedentary behavior questionnaire.

Values are median (25th-75th percentile).

Q1: questionnaire first application; Q2: questionnaire second application; rho: Spearman's correlation coefficient.

Significant values are in italics (p < 0.05).

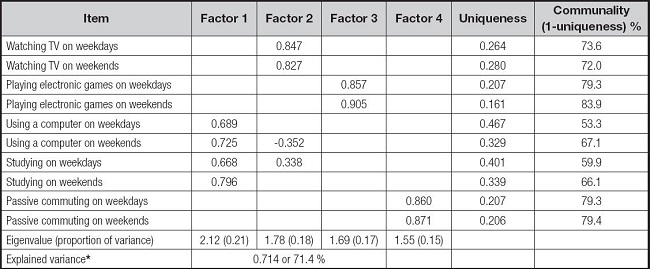

Regarding structural validity (Table III), our data were appropriate for exploratory factor analysis (KMO = 0.572; Bartlett's test, p < 0.001). We identified the following four factors: “studying and using a computer during the week” (Factor 1), “watching TV, using a computer and studying during the week” (Factor 2), “electronic games” (Factor 3) and “passive commuting” (Factor 4); together, these factors explained 71.4 % of the variance in the data. Based on the factor loading and analysis of commonality, no items were excluded.

Table III. Validity analysis (exploratory factor analysis) of the American Youth/Child Cardiovascular and Environmental (SAYCARE) sedentary behavior questionnaire.

A factor loading < 0.30 was not shown.

*Proportion and explained variance for the first 4 factors (factor 1, factor 2, factor 3, and factor 4) identified by using the eigenvalue greater than one rule (Kaiser's rule).

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to evaluate the psychometric properties of the SAYCARE questionnaire for assessing sedentary behavior among university students as well as the first to evaluate the feasibility of administering such a questionnaire in an online format in a low-income region. We found that the online SAYCARE questionnaire had acceptable temporal stability (reliability) and structural validity. Even though this questionnaire was developed for a face-to-face context, its psychometric properties were similar in a remote context (i.e., during social distancing, in an online format) as a viable alternative for collecting data in a pandemic context in a low-income region.

Although our sample varied in terms of age, sex and major, young women majoring in health sciences comprised the majority of respondents. These findings are in line with previous Brazilian epidemiological studies with university students (21,22), including those in low-income regions (17). In Brazil, young women account for the majority of enrolled in undergraduate health programs (23) who complete higher education degrees (24), which could potentially explain the demographic and academic distribution in our sample.

Our study indicates that the 10-item online SAYCARE questionnaire has acceptable reliability for measuring sedentary behavior among university students from low-income regions. These findings are in line with previous systematic reviews regarding the psychometric properties of subjective measures among youth (25) and adults (26). Although no previous study has assessed the reliability (and validity) of the SAYCARE questionnaire in adults (to our knowledge), this tool was reliable in young people in South America (18). Consistent with this finding, a systematic review and meta-analysis reported that questionnaires assessing sedentary behavior in epidemiological studies show moderate-to-good reliability; in addition, multiple-item questionnaires have slightly better reliability than single-item questionnaires (pooled correlation coefficient: 1-item = 0.34, 2-to-9-item = 0.35; ≥ 10-item = 0.37) (26). This pattern of reliability can be explained by the stable nature of the behaviors evaluated (e.g., computer use), since sedentary behaviors tend to be more stable than active behaviors (27). Additionally, we speculate that the sedentary behaviors studied are related to the university routine, which could reinforce this behavior pattern and consequently increase the precision of data.

Moreover, we found acceptable structural validity of the SAYCARE questionnaire among the university students studied. The structural validity of this questionnaire has not been studied to date, but studies on similar questionnaires have reported satisfactory criterion (25,28), concurrent (26,28), and structural (29,30) validity. The structural validity of the SAYCARE questionnaire can be explained by its construction (18), which included the following factors: i) construction by experts in behaviors related to energy expenditure; ii) inclusion of a range of typical behaviors (e.g., watching TV, using a computer or passive commuting), which seem sufficiently diverse and complementary in their domains; iii) questionnaire covering a longer recall period (e.g., weekday, weekend) and iv) validation against an objective instrument. Alternatively, the structural validity be attributed to the number of items in the SAYCARE questionnaire. A recent systematic review noted that questionnaires with fewer items (measured behaviors) have greater psychometric robustness, possibly because the participants may struggle with multiple-item questionnaires, making it difficult to replicate patterns and domains of sedentary behavior (26).

The present study has some limitations that should be noted, such as potential biases (including social desirability) and the lack of epidemiological representativeness of the sample (11). Regarding the latter, the current study was not designed to be representative of a specific population11; but, to reproduce with sufficient power at a given error level the psychometric properties of the SAYCARE questionnaire under planned population distribution (e.g., age range, biological sex and major) (11). Thus, the results should not be extrapolated beyond the psychometric findings. Although we observed a high rate of refusal to participate (57.0 % at Q1 and 34.2 % at Q2), post hoc analysis revealed that the power of the sample (lowest correlation observed = 0.31; n = 117) remained significant (β = 0.14; power = 0.86). Indeed, the included sample (n = 117) was larger than the planned amount (n = 98), partially attributable to the higher prediction (up to 50.0 %) of drop outs/missing data/refusal to participate incorporated in the study design grounded in our experience in questionnaire validity in the South American population (18). The research site was also selected by convenience, although the sample was randomly selected. These choices were based on the sociodemographic and academic diversity of the institution, which may provide a good idea of the characteristics of students from low-income regions, since representative methodological studies are not feasible (31) or ethical (14). We successfully recruited a sample with similar demographic and academic characteristics in the university context from low-income regions of Brazil (17,22). Finally, the questionnaire of interest should be evaluated in terms of external validation, preferably against objective data (e.g., using an accelerometer), to confirm its ability to measure the duration of sedentary behavior in this population (32). The strengths of this study were its methodology, involving epidemiological feasibility assumptions for assessing the psychometric properties of the (online) SAYCARE questionnaire; a robust sample, in terms of size and diversity, of Brazilian university students; and its adapted protocol to collect data during social distancing measures in low-income regions.

CONCLUSION

The SAYCARE questionnaire, in online format, exhibited acceptable reliability and validity for assessing sedentary behavior in university students from low-income regions. In this online format, the questionnaire represents a low-cost alternative to face-to-face administration (useful for conditions of restricted social contact).