INTRODUCTION

Low- and middle-income countries face a double burden of malnutrition in the form of micronutrient deficiencies, undernutrition, and overweight and obesity (conditions related to eating disorders and non-communicable diseases). Among the multiple reasons for this epidemiological phenomenon is the nutritional transition (1) — for example, Mexico has seen a reduction in stunting in children under five years of age from 26.9 % in 1988 (2) to 13.9 % in 2020 (3), but an increase in overweight and obesity (OW) across all age groups. In particular, women over 20 years of age have presented an alarming increase in OW from 34.5 % in 1988 (2) to 76 % in 2020 (4), representing an increase of over 100 % over three decades. Social feeding programs would therefore be expected to target the management and reduction of malnutrition and OW: however, that is not always the case. Social feeding programs in Mexico have historically targeted food insecurity and undernutrition through the distribution of food items (5).

Until its cancellation in 2018 (6), the Program for Social Inclusion (Prospera) was one of the flagship social programs in Mexico, originating in 1997 as a program of monetary transfers conditional upon attendance to preventative health check-ups, health and nutrition talks, distribution of nutritional supplements to pregnant women and pre-school aged children, and school enrollment for children and adolescents. The objective of Prospera was to improve the life conditions of families living in extreme poverty through improving health, education, and nutritional outcomes in both rural and urban zones (7). It achieved notoriety across Latin America, where similar programs emerged including “Progresando con solidaridad” in the Dominican Republic, “Más Familias en acción” in Colombia, “Bolsa familia” in Brazil, and “Red de Oportunidades” in Panama (8).

Multiple external impact evaluations on Prospera demonstrated positive effects on growth (9) and reduction of stunting and anemia (10) in pre-school aged children, and in the improvement of behavior in schoolchildren (11). However, these also highlighted an increase in OW in the adult population of beneficiary households (12). For this reason, the objective of the present study is to estimate the association between overweight and obesity and participation in conditional cash transfers (CCT) programs and other social feeding programs for women 15 to 49 years of age in the most economically vulnerable population groups in Mexico.

METHODS

Data for this analysis were derived from the Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey 100k (in Spanish, ENSANUT 100k): a probabilistic survey representative of the population in localities with under 100,000 inhabitants in Mexico and who live with the greatest prevalence of poverty (52 % of the population). ENSANUT 100k uses a stratified, multi-stage cluster design. Data was collected between March and June of 2018. Details on the design and sampling of ENSANUT 100k are described by Romero et al (13). Unprocessed data will be made available by the authors at any time.

STUDY VARIABLES

Overweight and obesity (OW)

Weight and height of the women in the study sample were measured by personnel trained and standardized using conventional protocols to obtain body mass index (BMI = kg/m2). BMI values outside the 10 to 58 range were considered invalid and eliminated. For adolescent women between 15 and 19 years of age, Z-score was calculated using the World Health Organization guidelines for that age group (14). Adolescents with Z-scores over +1 and under +2 SD were classified with overweight, and those with scores over +2 with obesity (15). BMI Z-score values between -5.0 and +5.0 was considered valid, in accordance with the known distribution of BMI for women of reproductive age in Mexico. Women aged 20 years or over with a BMI from 25.0 to 29.9 were classified as overweight, and those with a BMI above 30.0 were classified with obesity (16).

Social feeding programs

Information was obtained through a questionnaire applied to the female mother or head of household regarding the participation of her or her household in any food assistance program. Positive responses determined the classification of the women as a beneficiary of the program of interest. The programs with greatest coverage in Mexico during the year of data collection were a) Program for Social Inclusion (Prospera), b) distribution of food items to vulnerable families by the System for Wholistic Family Development (in Spanish, DIF), c) Social Program for Milk Distribution Liconsa (in Spanish, PASL), which distributes milk fortified with vitamins and minerals to vulnerable population groups, d) food assistance from non-governmental organizations (NGO's) e) DIF Community Kitchens, or f) Community Kitchens by the Secretariat of Social Development (in Spanish, SEDESOL).

Household food insecurity (FI)

FI was measured using the adapted version of the Latin America and the Caribbean Food Security Scale (in Spanish, ELCSA) (17). This scale has the objective to document the perception of household members around insufficient resources to get food or the worry that food will no longer be available (mild FI), reduced dietary diversity and quality (moderate FI), and limited quantity of food as well as hunger in adults and minors under 18 (severe FI) (18). The instrument uses 15 dichotomic questions (yes/no) applied to the household member responsible for food decisions and uses as period of reference the three months prior to survey application. Categories of FI are constructed using the raw number of positive responses. In households with children or adolescents under 18, a score of 0 = food security, 1-5 = mild FI, 6- 10 = moderate FI, and 11-15 = severe FI. For households without children or adolescents under 18, a score of 0 = food security, 1-3 = mild FI, 4-6 = moderate FI, and 7-8 = severe FI.

Education level

Maximum formal education level completed of participants was classified as a) none, b) primary or secondary, c) high school, or d) undergraduate or post-graduate.

Employment

Current employment status was classified as: a) employed; b) unpaid domestic work; c) student; or d) unemployed.

Wellbeing index (socioeconomic level)

An index was constructed through principal component analysis which considers variables describing dwelling characteristics (floor material, ceiling, walls, number of rooms, availability of running water, possession of an automobile), possession and number of electronic devices and services (television, cable service, computer, radio, telephone), and possession and number of large household appliances (refrigerator, stove, washing machine, hot water heater, microwave oven). The first principal component explained 40.5 % of total variation with a value (lambda) of 3,24. Wellbeing conditions were divided into quintiles, where the first quintile (Q1) represents the lowest wellbeing conditions.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Characteristics of the study population were described through proportions and 95% confidence intervals (95 % CI). Measurement of the association between OW and participation in social feeding programs resulted in odds ratios and confidence intervals adjusted for the different study covariables using a multiple logistic regression model. Statistical significance was set at < 0.05. Analyses were performed with consideration for the survey design and weighted for estimation at the national level, using the Stata 14.0 SVY module for complex samples (Stata Corp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14, 2015).

RESULTS

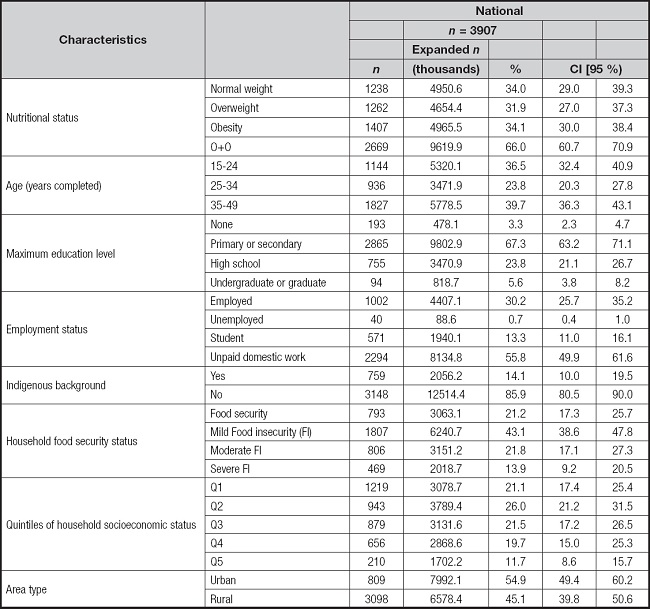

All data were obtained from 3,907 women aged 14-49 years, who represented 14,570,500 women from localities with < 100,000 inhabitants in Mexico. Average age was 30.7 ± 0.42. In all, 54.9 % (95 % CI, 49.4-60.2) of women lived in urban areas; 67.3 % (95 % CI, 63.2-71.1) of women had primary or secondary education, while 23.8 % (95 % CI, 21.1-26.7) had attended high school, 5.6 % (95 % CI, 3.8-8.2) had undergraduate or graduate degrees, and only 3.3 % (95 % CI, 2.3-4.7) had no formal education. In terms of employment status, 55.8 % (95 % CI, 49.9-61.6) of women performed unpaid domestic work, one of every three women were gainfully employed, and 13.3 % (95 % CI, 11.0-16.1) were students. A total of 78.8 % of women participants perceived some level of FI in their household (43.1 % mild FI, 21.8 % moderate FI, and 13.9 % severe FI), and 14.1 % (95 % CI, 10.0-19.5) of households spoke some indigenous language. Two in every three women 15-49 years of age residing in localities of < 100,000 inhabitants had overweight or obesity (Table I).

Table I. General and sociodemographic characteristics of Mexican women 15-49 years of age living in localities of < 100,000 inhabitants.

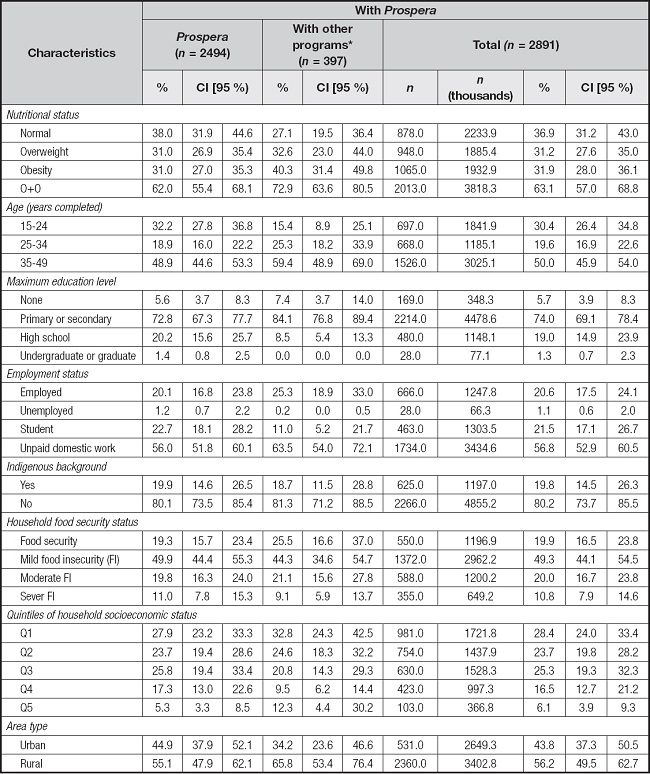

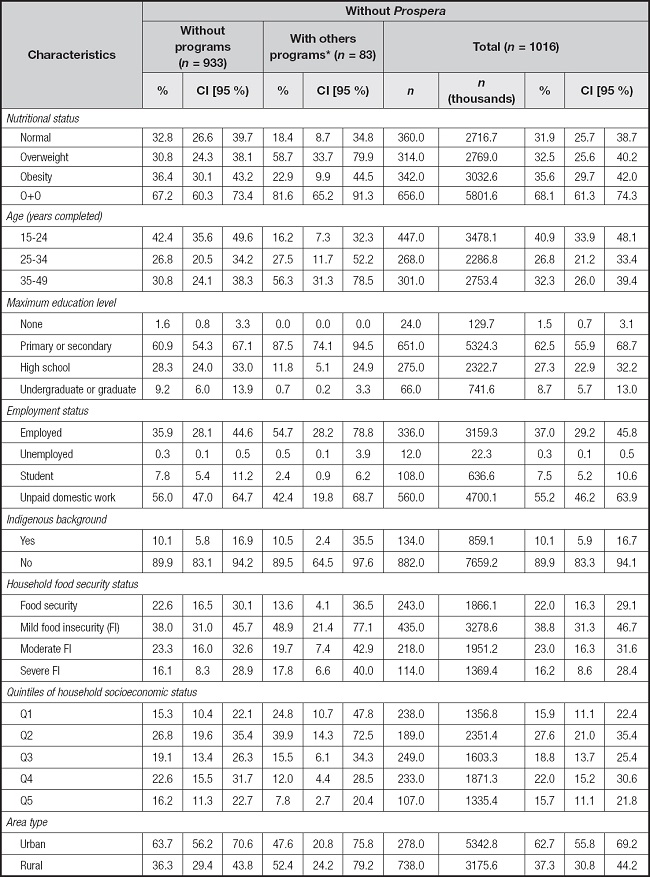

Of women who were beneficiaries of Prospera, OW prevalence was 63.1 % (95 % CI, 57.0-68.8) while in non-beneficiaries this was 68.1 % (95 % CI, 61.3-74.3) (p = 0.19). Among beneficiaries of any social feeding program, 62.0 % (95 % CI, 55.4-68.1) of women who only benefited from Prospera had overweight or obesity, while beneficiaries of other programs in addition to Prospera showed 72.9 % (95 % CI, 63.6-80.5) (p = 0.04). Women participating only in other programs (not including Prospera) showed an 81.6 % (95 % CI, 65.2-91.3) prevalence of OW and women who were not beneficiaries of any program showed 67.2 % (95 % CI, 60.3-73.4) (p = 0.07) (Tables II and III):

Table II. Characteristics of 15 to 49 year-old Mexican women living in localities of < 100,000 inhabitants with Prospera and others social feeding programs.

Prevalences and 95 % CI were obtained considering sample design of the ENSANUT 100K 2018 survey.

*Other programs: being beneficiary of one or more of the following social food programs: 1) DIF food distribution/assistance, 2) DIF Community Kitchens, 3) SEDESOL Community Kitchens, 4) Food/nutrition assistance from NGOs (food, nutritional supplements for children, micronutrients, support for food production), and 5) Social Program for Milk Distribution Liconsa.

Table III. Characteristics of 15 to 49 year-old Mexican women living in localities of < 100,000 inhabitants without Prospera and others social feeding programs.

Prevalences and 95 % CI, were obtained considering sample design of the ENSANUT 100K 2018 survey.

*Other programs: being beneficiary of one or more of the following social food programs: 1) DIF food distribution/assistance, 2) DIF Community Kitchens, 3) SEDESOL Community Kitchens, 4) Food/nutrition assistance from NGOs (food, nutritional supplements for children, micronutrients, support for food production) and 5) PASL milk distribution Liconsa..

Table II and table III show statistically significant percent differences in the education level of beneficiaries of Prospera, where 74.0 % (95 % CI, 69.1-78.4) have primary or secundary education compared to 62.5 % (95 % CI, 55.9-68.7) of non-beneficiary women. In contrast, just 1.3 % (95 % CI, 0.7-2.3) of beneficiaries of Prospera have a bachelor's degree as compared to 8.7 % (95 % CI, 5.7-13.0) of non-beneficiary women (p < 0.1). Significant differences were also evident in employment status, where 20.6 % (95 % CI, 17.5-24.1) of beneficiaries of Prospera were employed and 21.5 % (95 % CI, 17.1-26.7) were studying, as compared to 37.0 % and 7.5 % (95 % CI, 5.2-10.6), respectively, of non-beneficiaries (p < 0.01). No differences were observed between the percentage of women across both groups who performed unpaid domestic work (56.8 % vs. 55.2 %).

Other statistically significant differences (p < 0.01) were observed in in the distribution of wellbeing by quintile, where 28.4 % (95 % CI, 24.0-33.4) of beneficiaries of Prospera and 15.9 % (95 % CI, 11.1-22.4) of non-beneficiaries were in the lowest quintile of economic solvency (Tables II and III). Conversely, 6.1 % (95 % CI, 3.9-9.3) of beneficiaries and 15.7 % (95 % CI, 11.1-21.8) of non-beneficiaries were in the highest quintile; 56.2 % of beneficiaries of Prospera lived in rural areas as compared to only 37.3 % of non-beneficiaries (p < 0.01) (Tables II and III).

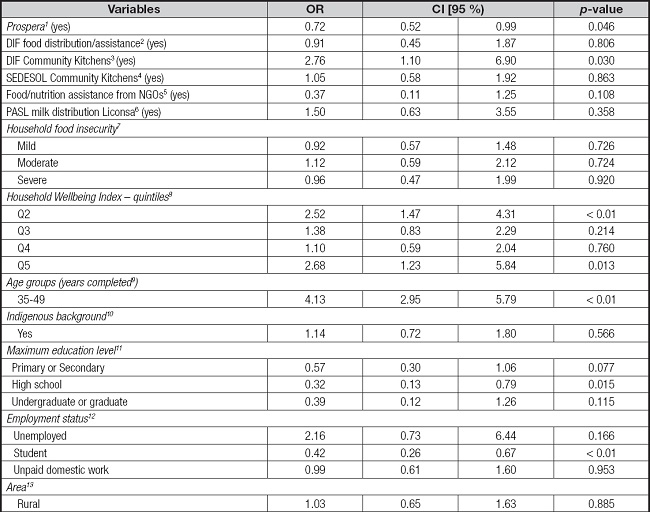

Table IV shows estimations of odds ratio (OR) with 95 % CI, where a logistic regression model adjusted for age and multiple sociodemographic variables was used to evaluate the association between OW and participation in social feeding programs for women 15-49 years of age. Odds of suffering OW were greater in women who participated in the DIF program Community Kitchens (OR = 2.76, 95 % CI, 1.10-6.90; p = 0.030), and being a beneficiary of Prospera was a protector associated for OW (OR = 0.72, 95 % CI, 0.52-0.99; p = 0.046). Furthermore, a risk association was present for women in both high and low wellbeing conditions, including Q2 (OR = 2.52, 95 % CI, 1.47-4.31; p < 0.01) and Q5 (OR = 2.68, 95 % CI, 1.23-5.84; p = 0.013), as well as women between 35 and 49 years of age (OR = 4.13, 95 % CI, 2.95-5.79; p < 0.01). Other protectors from OW in women were having an education level of high school or above (OR = 0.32, 95 % CI, 0.13-0.79; p = 0.015) and being currently engaged in studies rather than being employed (OR = 0.42, 95 % CI, 0.26-0.67; p < 0.01).

Table IV. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) between overweight and obesity and participation in social feeding programs for women 15-49 years of age.

1No receives benefits from other programs.

2No receives DIF food distribution/assistance.

3No receives DIF community kitchens.

4No receives SEDESOL community kitchens.

5No receives Food/nutrition assistance from NGOs.

6No receives PASL milk distribution Liconsa.

7Food security.

8Q1 Household Wellbeing Index.

9Age group ≥ 15 to ≤ 34.

10No indigenous background.

11Non-educational and preschool level.

12Employed.

13Urban area

DISCUSSION

In this study, participating in a social CCT program had a protective effect for OW for women 15-49 years of age residing in areas with under 100,000 inhabitants in Mexico. This reinforces a multitude of previous studies undertaken with beneficiaries of the Prospera program (previously called Oportunidades) when it was still ongoing. One randomized trial in 2003 found that rural adult beneficiaries 30-65 years of age who participated in this program for 3,5-5 years showed a lower prevalence of obesity (20.28 % vs. 25.31 %, p < 0.001) and overweight (59.2 % vs. 63.0 %, p = 0,03) as compared to the control group (19). Another study on Prospera in 2011 revealed a reduction in the rate of obesity in adolescent girls 15-21 years of age who had benefitted from the program for an average of four years in poor rural settings; the authors hypothesized, through a discontinuous regression design, that the effect could in fact be attributed to the mix of factors that the program offers, including access to schooling, information, improved diet quality, healthcare screenings, and physical activity (20). One analysis of the effect of the Prospera monetary transfers in urban areas which factored in the duration of time living there, showed a protective effect on overall body weight and abdominal fat of adults, particularly in younger populations (18-35 years). In beneficiary women, the protective effect was twice as strong for BMI (21).

Existing evidence therefore indicates that participation in CCT programs is important to preventing obesity. Furthermore, evidence has shown that women are particularly vulnerable to income inequality (22). The implementation of CCT has demonstrated positive impacts in combatting the simultaneous issues of poverty and obesity in Mexico (21). It is possible that the conditions set by this type of program, such as attendance at talks or workshops on food, nutrition, physical activity, and health, in addition to the mandatory attendance to periodic health screenings, offers women beneficiaries the elements needed to practice healthy behaviors. Consequently, these programs appear to protect against OW. In this sense, experimental and quasi-experimental studies among 18- and 65-years old participants from Oportunidades program, demonstrated effects over risk conducts, in general, they showed an improvement over healthy behavior (12,19).

In relation to our findings on the weight in the beneficiary population from the Prospera, external evaluations have shown different results to ours. In the initial stages of the program's operation in 2013, a study reported that duplication of cash transfers in the household was associated with a higher body mass index and a higher prevalence of overweight or obesity in the adult beneficiary population (23). Another study reported risk of weight gain in beneficiary women in 2004 (24). At the same time, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in the beneficiary population of women is similar to the figures or trends in the country (25). The potential explanations of these findings in women beneficiaries of Prospera, may be related to the fact that, due to the economic benefit present in the homes, it could lead to buying and consuming unhealthy foods, such as snacks or foods with a high energy content, which would contribute to the weight gain in the population. At that time, the increase in the prevalence of overweight or obesity in the Mexican population could also be partly explained by the greater availability of energy in this period (26). Regarding the energy supplement for women provided by the program from the beginning of its operation until 2013, there is no evidence that its consumption was related to weight gain in women (27). In addition, in 2014 the supplement was changed to one without energy (tablets with multiple micronutrients) in the context the integrated strategy for attention to nutrition (EsIAN, in Spanish) for the Prospera beneficiary population, which has documented favorable effects on health and nutrition outcomes in both children and women (28,29). Especially in women, the consumption of such a supplement did not show changes in weight between pregnancy and postpartum (28). Therefore, the benefits of the EsIAN could reflect favorable effects on the weight in the beneficiary women as those reflected in our findings. A prospective study in Colombia which evaluated the effect of CCT provided through program “Más Familias en Acción” on BMI and obesity in women living in poverty found that exposure to the program was significantly associated with greater BMI (β = 0.25; p = 0.03) and greater probability of obesity (OR = 1.27; p = 0.03) (30).

In the present study, participation in the DIF program Community Kitchens represented a risk factor for OW in women. In these Kitchens, which serve vulnerable populations, the food prepared is provided by DIF and often consists of non-perishable items, which are then complemented with fresh locally consumed foods. No monitoring exists on the food security or nutritional status of the population who use these spaces (31), which may explain in part the association found. Globally, little rigorous evidence exists to demonstrate the benefits of Community Kitchens. One systematic review highlighted the importance of Community Kitchens for low-income beneficiaries and their families in terms of social and nutritional health (32). Other results from this review led to the conclusion that it is possible to improve the budgeting skills of beneficiaries and in this way alleviate economic constraints on food security.

Our study found a significant risk association in older, as opposed to younger, age groups. Previous evidence has long shown that increased age is linked to an increased risk of obesity. In line with this, one study in the north of Iran found that the rate of obesity was greater in women than in men, and that this rate shows a statistically significant increase with age (33).

Another finding from our study is the association of OW with education level, where an inverse association was revealed between OW only in women with high school education or greater, as compared to those with no formal studies. Multiple studies have demonstrated that greater education level is negatively associated with OW (33,34). Devaux et al. (35) performed an analysis with data from health surveys in Australia, Canada, England, and South Korea, finding that greater education was associated with lesser probability for obesity, especially in women. Another study in California showed an inverse association with education level and BMI; that is, as education level increases, BMI decreases (36). The same was found in Paraguay, where an analysis of three national health surveys showed a greater prevalence of OW in those with lower education as compared to those with higher education (37).

In this study, we also observed a positive association between OW and the highest wellbeing conditions (Q5) in women; nonetheless, the same association was shown for Q2. Reviews which aim to analyze the association between obesity and socioeconomic status (SES) have found that women in middle-income countries with lower SES have the highest prevalence of obesity, and that in low-income countries the prevalence of obesity in women is higher with higher SES (38,39). One study with women participating in food assistance programs in Peru demonstrated an association between program participation and the risk of suffering OW in households without poverty indicators. The authors argue in favor of improved program and product targeting to ensure that women at higher risk of overweight do not receive excess calories through the energy-dense food distributed by certain programs (40).

One limitation of our study was that it did not consider individual variables which may contribute to OW such as energy consumption, dietary diversity, and physical activity.

It is critical that the scientific evidence produced through rich experiences with programs such as Prospera be used to shape public policy and social feeding programs. This will allow the largest contemporary health and nutrition problems in the Mexican population to be addressed. Although the Prospera program is no longer active in Mexico, analysis of the data generated in the beneficiary population over the years it was in place continues to be key to decision-making around the provision and design of other national programs. In addition, these analyses generate evidence on the utility of monetary transfers across contexts.