INTRODUCTION

Malnutrition affects physical, mental and social development, especially in children (1). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines malnutrition as the product of “deficiencies, excesses and imbalances in a person’s caloric and/or nutrient intake”, this definition includes both undernutrition and overweight and obesity (1). Multiple studies have documented that children with undernutrition have a higher risk of dying from any cause, an increased risk of infectious and respiratory diseases, diarrhea, anemia, as well as poor physical and cognitive development (1,2). On the other hand, overweight and obesity in children are associated with lower self-esteem and an increased risk of skin and orthopedic diseases, as well as a higher risk of developing lipid abnormalities, sleep apnea, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and some types of cancer in adulthood (1,2).

The children with the highest risk of malnutrition are those who are in vulnerable environments, that is, they live in rural communities or in low-income households or belong to an indigenous community or ethnic minority (3). Globally, 18.4 % of children between the ages of 5 and 19 were overweight and obese in 2016 (4). Although developed countries have the highest prevalence, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have seen a significant increase in their rates of obesity and overweight in the last decade (4). Undernutrition in schoolchildren is rarely reported worldwide, but several local studies have shown that rural and indigenous communities in LMICs are the most affected (2). Malnutrition can occur due to limited access to nutritious food as in food insecurity (FI).

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) defines FI as “the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways” (5). FI is associated with multiple health problems, including a higher risk of asthma, anemia, cognitive problems, anxiety and depression, than people who are food secure (6-8). In the world, 29.3 % of people were moderately or severely food insecure in 2021, with LMICs, such as Africa (57.9 %) and Latin America and the Caribbean (40.6 %), having the highest prevalence (2).

Multiple studies have evaluated the relationship between FI and malnutrition. In the case of adults and adolescents, a higher level of FI is associated with a higher prevalence of overweight and obesity, particularly in women (9,10). In contrast, in preschool children (< 5 years), higher levels of FI are associated with an increased risk of developing undernutrition (10,11). In relation to schoolchildren (5 to 12 years), higher levels of FI have been associated with lower diet quality (12). Schoolchildren with FI have a lower consumption of fruits, vegetables, fiber, legumes, as well as a higher intake of calories, mainly from saturated fats and added sugars than their peers without FI (13-16). This indicates that schoolchildren with FI have a greater risk of malnutrition than those without FI.

A century ago, being overweight and obese was associated with wealth, but not anymore. In developed countries, poor children are often the most likely to be overweight or obese (17).

Children who are overweight often come from socioeconomically disadvantaged families. In the United States, for example, the rate of overweight in children decreases as educational level and family income increase (18). Sopoede et al. conducted a systematic review whose objective was to evaluate the relationship between FI and malnutrition in children aged 2 to 19 years in the US (19). The authors concluded that there is no evidence showing a relationship between FI and undernutrition. In relation to FI and overweight and obesity, the results were not consistent, but there seems to be a trend towards a higher risk of obesity. For schoolchildren (5-12 years) in LMICs, little is known about the relationship between FI and malnutrition. The purpose of this review is to study the relationship between FI and nutritional status in schoolchildren with characteristics of vulnerability from LMICs.

METHODS

CRITERIA FOR CONSIDERING STUDIES FOR THIS REVIEW

Participants

The population was schoolchildren (5 to 12 years) in conditions of vulnerability from LMICs. Vulnerability was considered when they lived in a rural community, had a low socioeconomic level and/or belonged to an Indigenous community or ethnic minority. Studies in which the majority of participants (more than 80 %) are in this age range or present separate data for this age range were included.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes were BMI-for-age Z-score (BMI-Z), odds ratio (OR)/relative risk (RR) for undernutrition, and OR/RR for overweight and obesity. Other anthropometric measures such as weight, waist circumference, skinfolds, height-for-age Z-score (HAZ), weight-for-age Z-score (WAZ), weight-for-height Z-score (WHZ) as well as the prevalence/incidence of malnutrition and prevalence/incidence of overweight and obesity were considered secondary outcomes.

SEARCH STRATEGY

The search for articles was performed using the databases PubMed (interface National Library of Medicine), MEDLINE (OVID interface), The Cochrane Library – CENTRAL (OVID interface), LILACS (Virtual Health Library) and SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online). The search was conducted during the months of March to April 2022 without language or publication date restrictions. The search strategy consisted of combinations of text words and controlled vocabulary (MeSH terms and DeCS) related to “schoolchildren”, “low- and middle-income countries” and “food insecurity” considering the search platform. The PubMed search strategy can be found in the supplementary material (Supplementary Table I). Following the recommendations of the Cochrane handbook, the bibliographical references of systematic reviews and included studies were considered as additional search sources (20).

SELECTION OF STUDIES

For the article selection process, the Mendeley version 1.19.8 software was used, to which the results of the searches in the different databases were imported for subsequent processing. In the first stage, duplicate results were removed. In the second stage, titles and abstracts were reviewed eliminating articles that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria. If the inclusion criteria were not well defined in the abstract, the article went to the third stage. In the third stage, the full text was reviewed to assess whether it met the inclusion criteria. The study selection process is described in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1).

DATA EXTRACTION AND SYNTHESIS

For data extraction, an electronic format (Excel sheet) was used, which collected the title of the article, author, year of publication, type of study, study population, number of participants, measurement tools and cut-off points for FI and malnutrition, in addition to the main results. The information collected from the included studies is presented through a narrative synthesis.

RESULTS

CHARACTERISTICS OF INCLUDED STUDIES

Of the 36 full-text articles that were evaluated, nine did not evaluate the relationship between FI and malnutrition, five did not meet the age criteria, and seven were not conducted in LMICs (Fig. 1). The 15 studies included in the review had a cross-sectional design and were published between 2007 and 2021 (6,21,30-34,22-29). These studies analyzed populations from Brazil (21,31), Ethiopia (23,30), the Philippines (24), Malaysia (25), Venezuela (27), Nicaragua (6), Colombia (34), Bolivia (22), Mexico (26,28,29,33) and Jamaica (32). The sample size ranged from 61 to 7181 schoolchildren, and all studies had vulnerability characteristics.

Nine different tools were used to assess FI, eight of which assessed FI at the household level and one at the personal level. The tools used were Brazilian Food Insecurity Scale (EBIA) (21,31), Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) (22,23), Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) (24), Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity Instrument (25), USDA Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) (34) and its version short (27), Latin American and Caribbean Food Security Questionnaire (ELCSA) (6,29), Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance (FANTA) (30), Mexican Food Safety Scale (EMSA) (26,28) and 2-items Hunger Vital Sign (HVS) (32,33).

To assess nutritional status, BMI-Z, HAZ, WAZ and WHZ were used. To classify children, 12 studies used the WHO 2007 cut-off points (21,22,31,34,23-30), one the CDC 2000 cut-off points (33), one the Frisancho 2008 cut-off points (6), and one the Cole references specific for sex and age (32).

FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION

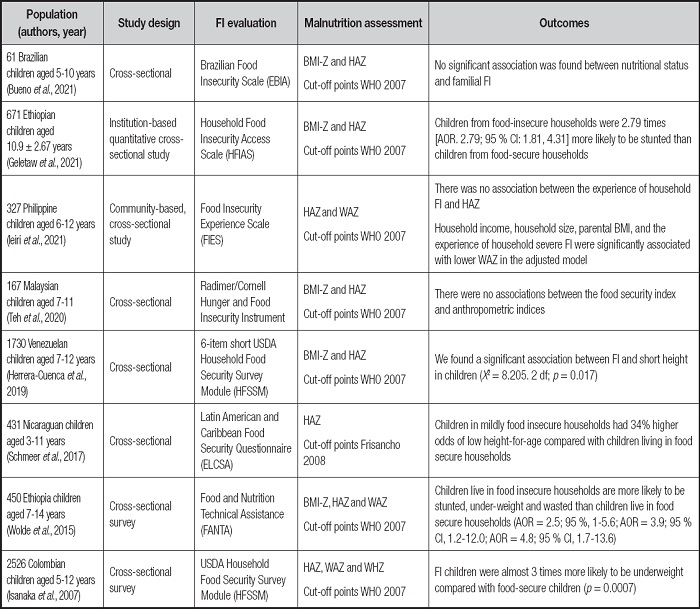

Eight articles evaluated the relationship between FI and undernutrition, the summary of results is shown in table I. Three studies found that higher levels of FI were associated with an increased risk (OR, 1.34 to 2.79) of stunted (measurement by HAZ) in schoolchildren (6,23,27). However, Ieiri et al. could not find a significant association between FI and HAZ, but did find a significant association between FI and lower WAZ (24). In agreement, two studies showed that schoolchildren with FI have a higher risk of low WAZ (OR, 3.0 to 4.8) compared to children without FI (30,34). Two studies found no significant association between FI and anthropometric indices (21,25).

FOOD INSECURITY AND OVERWEIGHT OR OBESITY

Nine articles evaluated the relationship between FI and overweight or obesity, the summary of results is shown in table II. Two studies conducted in Mexican schoolchildren found that higher levels of FI were associated with an increased risk of overweight and obesity (OR, 2.3) (28,33). However, Murillo-Castillo et al. and Shamah-Levy et al. found that higher levels of FI were associated with lower prevalence of overweight and obesity in Mexican schoolchildren (26,29). Similarly, two studies conducted in schoolchildren in Brazil and Jamaica found the same negative association between FI and lower risk of overweight and obesity (OR, 0.78 and OR, 0.65, respectively) (31,32). Bethancourt et al. found that FI and hair cortisol concentration were associated with a lower BMI-Z, in turn, FI was associated with a higher percentage of body fat in Bolivian schoolchildren (22).

DISCUSSION

LMICs are the most affected by FI and malnutrition. Children with FI and malnutrition have less physical, mental and social development in addition to more health problems(1,2,6,8). Knowing the relationship between FI and malnutrition, as well as its determinants, can allow the development of better strategies for its approach. However, evaluating the association between FI and malnutrition in schoolchildren is complicated because both problems are multifactorial.

There are many validated tools to assess FI and nutritional status, further complicating the association between FI and malnutrition. FI can be assessed at a household or personal level. In this review, nine different tools for assessing FI were identified, with eight at the household level and one at the personal level. Household-level surveys include a section to capture children’s experience, however, when answered by the head of the household, they identify FI globally (35). Various authors have suggested that parents’ perceptions of their children’s FI could be imprecise or incomplete (36,37). This may be because not all members of the same household deal with FI in the same way (38). Parents may not be fully aware of their children’s experiences or the actions they take to reduce the severity of FI (39). Research suggests that this discrepancy may be due to different ways of reasoning and response styles (36-39).

Studies evaluating the reliability of schoolchildren reporting their own experiences of FI concluded that those aged between 6 and 16 years are capable of doing so (37,40). In the USA, Connell et al. developed the Children Food Security Survey (CFSS), which adapted 9 questions from the HFSSM for use with children aged between 12 and 17 years (40). The CFSS demonstrated acceptable reliability and apparent internal validity (40). A study comparing the diet quality with FI levels, using both the HFSSM and CFSS for measurement, concluded that both surveys concurred in classifying FI as long as the child was ≥ 6 years old (41). However, the author suggested that the CFSS might be more sensitive in detecting differences in micronutrient intake (41).

The studies included in this review used the BMI-Z, HAZ, WAZ and WHZ indices to define malnutrition. Two of the studies included in this review did not find a significant association between FI and anthropometric indices (21,25). Nutritional status is normally defined by anthropometric indices, however, there are other tools that can aid in a more comprehensive evaluation. Nutritional status is defined as the physical condition resulting from the relationship between individual requirements and the consumption, absorption and use of energy and nutrients (1). Therefore, for a comprehensive nutritional assessment, one must consider not only anthropometric parameters, but also macro and micronutrient intake, as well as physical activity levels and the child’s medical history. Some studies suggest that the lack of association between FI and malnutrition may be attributed to potential confounding variables, including the child’s sex and age, household income level, parents’ nutritional status, and ethnicity (42-44).

Of the eight articles in this review that evaluated the association between FI and undernutrition, six of them showed significant associations between higher FI and greater risk of stunted and undernutrition in general. Various theories have been proposed as possible causes of lower HAZ in schoolchildren with FI, such as delayed introduction of supplemental foods, or the introduction of poorly nutritious foods rich in starch and low in protein, vitamin A, iron and zinc (16). On the other hand, an analysis of eating habits in relation to FI levels showed that diet quality decreases with increasing FI. Children with FI have a higher intake of calories from saturated fats and added sugars, as well as a lower intake of fruits, vegetables, and dairy products (12-15,45). These eating patterns suggest an increased risk of obesity in children with FI.

Examining the intriguing relationship between FI and a reduced risk of excess weight, particularly overweight and obesity, reveals a noteworthy pattern in our reviewed studies. Five out of the nine studies investigating the FI-overweight/obesity link reported a lower prevalence of these conditions, as indicated by a lower BMI-Z, among children experiencing FI. This trend, observed predominantly in developing countries, contrasts with patterns in developed nations, where higher FI levels often correlate with increased prevalence of overweight and obesity. The variations observed across different socio-economic contexts, food availability, accessibility, and levels of physical activity might account for these disparities (42-44).

In the global issue of overweight and obesity, it is noteworthy that, while developed countries exhibit the highest rates of these conditions, LMICs have experienced a significant increase in their rates over the past decade (4). This phenomenon is intertwined with the complex relationship between FI and overweight or obesity, as revealed by nine studies analyzed in this review. Of these, five demonstrate that children facing FI have lower prevalences of overweight and obesity. However, these same studies agree that the quality of the diet is compromised, reflected in reduced consumption of fruits and vegetables, as well as increased intake of simple carbohydrates and saturated fats, which over time could contribute to the development of overweight or obesity (22,26,29,31,32).

It is important to note that the apparent lack of association between FI and a higher prevalence of overweight and obesity can be explained by the nutritional transition phase these countries are undergoing, where a dual burden of malnutrition is observed in the same household. One study highlights that FI is associated with stunting in preschoolers only if the mother does not suffer from obesity (29). The disparity in the relationship between FI and overweight or obesity between developed and developing LMICs may be due to divergent trajectories. While in developed countries, available social support services are associated with an increase in overweight/obesity, in developing countries, limited assistance in the form of food subsidies contributes to children from poorer families with FI consuming fewer total calories, thereby decreasing the chances of developing overweight or obesity (32,46,47).

However, it is crucial to note that the association between FI and excess body fat was highlighted in the study by Bethancourt et al., demonstrating a higher percentage of body fat in schoolchildren experiencing FI (22). Similarly, the studies conducted by Rosas et al. and Ortiz-Hernández et al. found a higher risk of overweight and obesity among schoolchildren facing FI (28,33). The complexities of the relationship between FI and obesity are multifaceted and encompass factors such as the consumption of cheaper and more energy-dense foods, periods of insufficient food leading to overeating when available, and fluctuations in eating habits within families experiencing FI (48).

Schoolchildren living in vulnerable environments are at higher risk of experiencing a high prevalence of FI and malnutrition (2,3). Knowing the social determinants associated with FI and malnutrition will allow the creation of better approach strategies. As a strength, this review shows how FI may be related to malnutrition in schoolchildren (5 to 12 years) from LMICs. A limitation of this review is that the included studies had a cross-sectional design that precludes establishing causal relationships, so more research is recommended to explain how FI is related to malnutrition in schoolchildren through stronger epidemiological designs. Additional investigations may also be conducted to determine if there are other social determinants associated with these factors. These social determinants may include family structure, socioeconomic and educational level, access to resources, among others.

CONCLUSION

The present systematic review addressed the complex relationship between FI and malnutrition in schoolchildren from low- and middle-income countries. Analyzing 15 cross-sectional studies revealed significant variability in the findings. Concerning undernutrition, the majority of studies indicate an association between elevated levels of FI and an increased risk of low HAZ or low WAZ. However, discrepancies surfaced, with certain studies failing to establish a significant link between FI and anthropometric indices. Regarding overweight and obesity, the evidence presented conflicting results, with studies suggesting both positive and negative associations between FI and these health issues. The diverse outcomes underscore the necessity of considering contextual and population-specific factors when interpreting the relationship between FI and nutritional status.

These findings highlight the complexity of the relationship between FI and malnutrition in schoolchildren, suggesting that socioeconomic, cultural, and regional factors may significantly shape this association. The emphasis is placed on comprehensively addressing FI in public health policies, considering the various dimensions of nutritional status in school populations across diverse contexts.