INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a health condition that affects millions of people worldwide, and its treatment is a challenge that requires a multidisciplinary approach.

According to the Spanish agency for food safety (Agencia Española de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición, AESAN) and the National epidemiology center of health (Instituto Carlos III, ISCIII), in 2023, 4.9 % of the adult population residing in Spain suffers from severe obesity (mass index (BMI) > 35 kg/m2) and 1 % have a BMI > 40 (1).

The World Health Organization (WHO) highlights that obesity is responsible for 10-13 % of deaths worldwide (2). When compared to medical treatment, metabolic/bariatric surgery (MBS) has proven to be one of the most effective treatments for patients with severe obesity (3). MBS maintains its effectiveness after the intervention and reduces the risk of other associated comorbidities (4). In fact, studies provide evidence of a substantial reduction in mortality in patients with severe obesity who undergo MBS, along with reduced healthcare utilization and a drop in direct medical costs (2,5).

Worldwide, the number of MBS procedures performed exceeded 800,000 in 2019 (6). According to the ENRICA study, “Estudio de Nutrición y Riesgo Cardiovascular en España” (7), the number of MBS interventions performed has been increasing in Spain, reaching 6,000-7,000 procedures per year in 2023. According to estimates, Spain had over 11,000 patients awaiting MBS in 2022 (8).

MBS improves quality of life and perceived health status, with changes observed in the first year and benefits retained for up to ten years or more (9). However, it is not always the most appropriate treatment for all patients (10). Not all people undergo MBS have a favorable outcome (11) and indeed, for many patients, weight recurrence is a compelling problem that arises between 1 and 3 years after surgery. In addition, in smaller subsets of patients, MBS is associated with an increased risk for substance abuse, self-harm and suicidal ideation, attempts or suicidal death (9). For these reasons, it is necessary to establish careful assessment and preparation procedures for individuals who are seeking MBS.

Rates of psychopathology for any psychiatric disorder across the lifespan are elevated in people seeking MBS, being close to 50 % for the 45-59 age group study (12). The most common psychiatric disorders in this population are affective and anxiety disorders, as well as binge eating disorders (13). Preoperative psychopathology may pose a challenge to adjustment and adherence after surgery as it is associated with longer hospital stays, increased complications and readmission rates (14). Patients behaviors after surgery also influence substantially long-term outcomes (14). While there is a dearth of strong, consistent evidence that pre-operative mental health conditions or eating disorders are associated with postoperative weight outcomes (15), some studies show that patients with greater social complexity showed a greater increase in BMI at 10 years after surgery relative to those without (11). Further, when eating pathology and depression symptoms recur after MBS, poorer weight loss outcomes were reported (9).

Therefore, preoperative psychosocial evaluation is crucial for optimizing the outcomes of patients seeking MBS. It is a way to identify strengths and vulnerabilities and develop recommendations to enhance surgical outcome (14). As early as 1991, the NIH Consensus Statement recommended that patients seeking MBS should be evaluated by a “multidisciplinary team with access to medical, surgical, psychiatric, and nutritional expertise” (5). Since then, the value of such evaluations has continued to be emphasized (5,16,17).

Bauchowitz et al. (2005) reported that the majority of pre-MBS programs (86.4 %) required a psychological evaluation to approve the procedure (18). However, the current view of the goal of the pre-MBS psychosocial assessment is not to provide a dichotomous recommendation about “clearance” — rather, the goal is to assess for risk factors and potential challenges to the patient smoothly navigating the demands of surgery, body image changes, and lifestyle changes required after surgery. Examples include uncontrolled psychiatric symptoms, active substance abuse, severe stressors, economic challenges, etc. Furthermore, when such potential challenges are identified in the pre-operative assessment, the goal is to address them, to optimize post-operative outcomes (5). One factor that complicates the assessment of patients seeking MBS is that in many settings, there is little connection and/or sparse communication between the evaluating mental health clinician and the MBS team. For instance, Bauchowitz et al. (2005) found that only 25.9 % of MBS programs had their own mental health professional on staff, while 65 % referred patients to mental health professionals in the community.

In this context, the Boston Interview for Bariatric Surgery (BIBS) (19) is a valuable tool in the psychosocial assessment process of people seeking MBS. It provides a framework for exploring psychosocial dimensions, allowing mental health professionals from diverse backgrounds to obtain a more complete picture of the patient's readiness for surgery and the lifestyle changes that will follow. Its content areas align closely with the American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) recommendations for the psychological assessment of people seeking MBS (20). It is designed to provide a standardized but flexible and individualized way of working that allows mental health professionals to gather consistent and comparable information on known psychological factors that may influence the outcome of intervention. In addition, it can provide a standardized and agreed method for collecting data for research and a reliable guide to professionals who are training in the psychosocial assessment of people seeking MBS.

The BIBS has been translated into Italian and is recommended by the Italian Society of Obesity Surgery (SICOB) (2011) as one of the tools to adopt for preoperative psychological assessment (21).

In 2023, almost 500 million people worldwide will have Spanish as their mother tongue, representing 6.2 % of the world's population. It is the second-most common native language based on number of speakers (22). However, despite the prevalence of Spanish in the world, there is no standardized interview model in Spanish to assess the psychological readiness of people seeking MBS. This represents a barrier for Spanish-speaking patients seeking MBS treatment. Adapting tools that are already used in other countries would allow the implementation of the knowledge acquired, save efforts in the development of a tool and have greater validity and generalizability as data are taken from different population (23). Even though most guidelines assume that theoretical constructs are similar in both cultures (conceptual equivalence) and that therefore a semantic and linguistic adaptation suffices (23), cross-cultural adaptation is fundamental to guarantee the adequacy of an instrument in a different culture, ensuring that it remains equivalent to the original version, while being relevant to the cultures in which it is being used (24). The cross-cultural adaptation involves not just converting words from one language to another, but also accounting for differences in cultural contexts, expressions, and sensitivities, using forward and back translations and committee consensus approaches to resolve ambiguities or discrepancies and to reach agreement to adapt terms culturally (23). This approach ensures that linguistic and cultural nuances are accurately conveyed and potential misinterpretations or misunderstandings stemming from cultural disparities can be minimized.

The translation of the BIBS into Spanish is an important step to make the preoperative psychosocial assessment more accessible to patients and more standardized for the use of professionals. It is the aim of this paper to present the process of translation into Spanish and cross-cultural adaptation of the BIBS.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The Boston Interview for Bariatric Surgery (BIBS) consists of an initial introductory section in which basic sociodemographic information is collected and 7 sections that evaluates dietary history and eating habits, screen for eating disorders, medical history and the knowledge about specific surgical procedures, including the risks and post-surgical regimen, motivation and expectations for the surgery, strength of patient's support systems and relationships, and finally, a psychiatric evaluation. It should be noted that, having been published in 2008, the BIBS includes material relating only to the two procedures most commonly performed at that time, the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band and the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) (Annex 1: https://www.nutricionhospitalaria.org/anexos/05254-01.pdf).

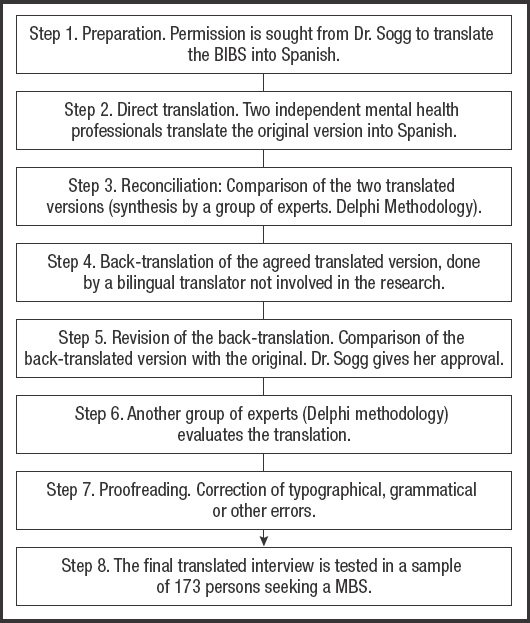

The original version of the BIBS was translated following the back-translation procedure based on the suggested principles for translation and interculturality of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) (25 26 27-28). The steps followed are summarized in figure 1.

The research was carried out after having requested the relevant authorization from the ethics committee of the University Hospital Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda in Madrid (HPHM Madrid, Spain. PI: 75/22).

Dr. Sogg, the first author of the original, English-language version of the BIBS, was contacted to request her permission/authorization to translate and adapt it. As the BIBS in its revised version was updated in 2008 (19), it was recommended by the author to update some of the items using the DSM-5 as well as to implement the suggested criteria for “night eating syndrome”. In addition, it was agreed to update the information included in the section “Understanding surgical procedures, risks and postoperative regimen”, to add the types of bariatric interventions used in our setting: vertical sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass.

Two independent bilingual professionals whose native language was Spanish translated the original version of the BIBS into Spanish (Annex 2: https://www.nutricionhospitalaria.org/anexos/05254-02.pdf). Both versions were collated to create a common version that was reviewed by a group of experts (3 psychiatrists with experience in the evaluation of severe obesity) and consensus corrections were introduced following a methodology similar to the e-Delphi (29). Once the final version was agreed upon, a native bilingual translator other than the initial translator, who was not involved in MBS assessments, retranslated it into English. This version was compared with the original English version, focusing on conceptual equivalence and linguistic consistency, prioritizing the comprehensibility and meaning of the content, rather than literal equivalence of the verbiage. No significant discrepancies were observed between the two versions. Finally, the translated version was shared with the authors of the BIBS and their suggestions were incorporated to establish the definitive Spanish version.

Since this interview is designed as a support for the clinician who adapts the questions to the context and reality of each patient, and since there is no standard measure of comparison established in the MBS population, expert judgment was used to verify that it was understandable and culturally adapted to our environment. A group of experts from different specialties (general surgeons, endocrinologists, psychologists and psychiatrists) was formed; including professionals accustomed to evaluating patients who were people seeking MBS. The input of professionals who are knowledgeable about MBS but are not mental health clinicians was included since some sections of the interview focused on technical and nutritional aspects of the surgery. Finally, three men and six women between 35 and 55 years of age, which was considered sufficient (29), formed the group of experts. Of them, three were endocrinologists with specialization in nutrition, three were general surgeons dedicated to metabolic surgery, two were psychiatrists, and one was a psychologist with specialization in the MBS evaluation.

An online survey was designed grouping the questions into 23 sections by thematic content and length. In each section, respondents were asked if the questions were understandable (clarity of wording) and appropriately culturally adapted using a Likert scale with ratings 0 to 3 (0: deficient, 1: acceptable, 2: good, and 3: excellent). The first four sections were only assessed by the mental health specialists (psychiatrists and psychologist) as these sections focused on specific aspects of mental health evaluation. In addition to the Likert scale questions, a free response section was added to suggest changes in the translation to improve comprehension and adaptation. In this last section, the comments offered were grouped into four categories (1. no modifications, 2. typographic mistakes, 3. slight suggestions that did not modify the original meaning, and 4. comments proposing changes in the meaning of the original question). Except for this last category, the suggestions made were introduced in the translated final version. Again, an e-Delphi methodology (29) was used to collect the experts' responses. Only one round of questions was necessary because the assessment was good and the agreement high. It was considered that the response rates in a second round would not be much different from the results already obtained.

The translated interview was also used to evaluate 173 patients who were people seeking MBS referred to the mental health service of the HPHM from June 2022 to December 2024. No patient refused to participate in the study. Only those patients who were already being treated by other mental health professionals were excluded as the evaluation was preferably done by their Mental Health providers. After the interview, all of the people interviewed were asked to rate their satisfaction with the interview experience on a Likert scale of 0-10 (0: very dissatisfied and 10: very satisfied). It is repeatedly proposed in the literature, that people seeking MBS may be biased in their reporting because they fear a negative evaluation that may prevent them from having surgery (30,31). To minimize this bias, assessments from people seeking MBS were anonymized with a code, and it was explained to them that it would have no influence on their subsequent evaluation or care.

The sociodemographic characteristics of the people seeking MBS evaluated were: 111 women (64.2 %) and 62 men (35.8 %), aged between 18 and 63 years (mean: 46.93, SD: 10.94). Of these, 130 came from Spain (75.1 %), 35 came from Latin America (20.2 %) and the remaining subjects had other nationalities—8 (4.6 %). In relation to level of education: no education or basic education, 35 (20.3 %); university, 55 (31.4 %); and secondary education, 83 (vocational training and high school: 48.3 %). Of the patients evaluated, 14 (8.1 %) did not answer the satisfaction survey. The sociodemographic characteristics of those who did not answer were similar to those who responded, with no statistically significant differences being found between the two samples in relation to age, education or sex.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The data is presented as absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables and as mean and standard deviation or median and 25th and 75th percentiles for numerical variables. The percentage of agreement between the different medical specialties was estimated with the corresponding 95 % confidence interval.

The statistical analysis was performed with the Stata v18 statistical package (StataCorp. 2023. Stata Statistical Software: Release 18. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

RESULTS

RESULTS OF THE ANALYSIS OF THE BIBS BY THE GROUP OF EXPERTS

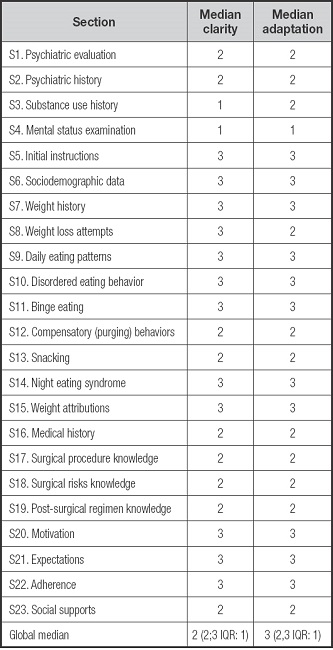

From the analysis of the surveys carried out by the group of experts, the median scores in each section ranged from 2: good to 3: excellent (Table I), except for sections 3 (writing) and 4 (writing and adaptation), which were rated 1: acceptable. The overall median rating of the quality of writing was 2: good, and for cultural adaptation was 3: excellent. The overall mode and median were 3: excellent. The overall IQR (interquartile range) was 1 for both questions, which was considered consensus (29).

Table I. Medians of the evaluations of each section for “clarity of wording” and “cultural adaptation” (n = 173).

0: poor; 1: acceptable; 2: good; 3: excellent.

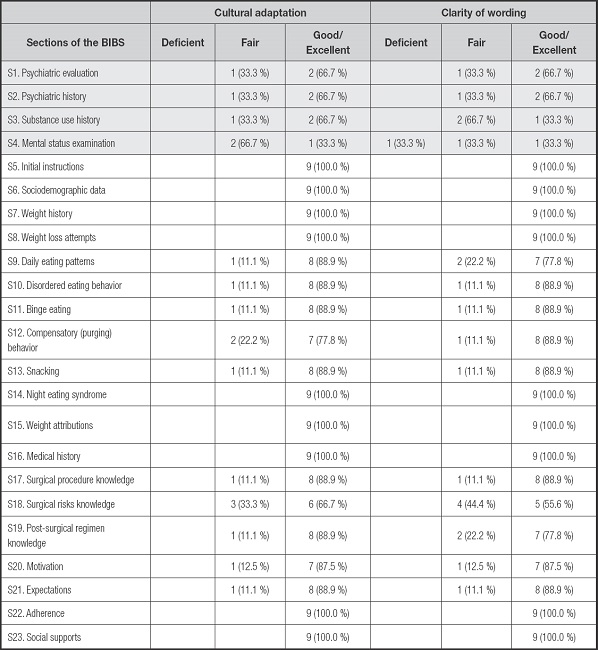

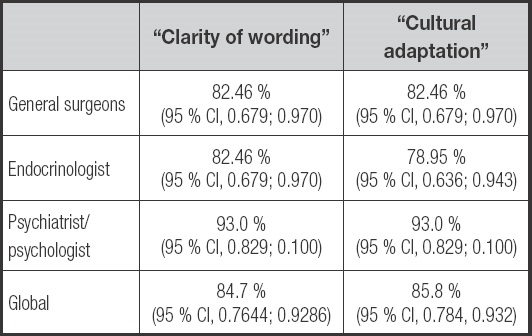

In addition, the percentages of agreement in each section were obtained. Table II shows the percentages obtained in relation to cultural adaptation and clarity of wording.

Table II. Agreement for each section on “cultural adaptation” and “clarity of wording” (n = 3 for S1 to S4 for highlighted results, n = 9 for the rest).

As it can be seen in the table, only in section 4 was the clarity of writing considered deficient by one of the evaluators. The section with the lowest rate of agreement for cultural adaptation was the one related to history taking and psychopathological examination (33 % agreement). In the remaining sections of cultural adaptation, the percentage of good/excellent had a range of 66.7 % to 100 %.

For clarity of wording, sections 3 and 4 related to substance use history and psychopathological history and examination, were the sections with the lowest ratings. In the rest of the sections, the percentage of good/excellent for clarity of writing ranged from 66.6 % to 100 %.

Table III shows the percentages of agreement for the different groups of specialists. There were no relevant differences (p < 0.05) between the various specialists. The overall percentage of agreement rating the question on the cultural adaptation of the text as good/excellent was 85.8 % (95 % CI, 0.784, 0.932). The percentage of overall agreement rating it as good/excellent was 84.7 % (95 % CI, 0.7644; 0.9286).

Table III. Percentages of agreement for the different groups of specialists related to “clarity of wording” and “cultural adaptation” (n = 23).

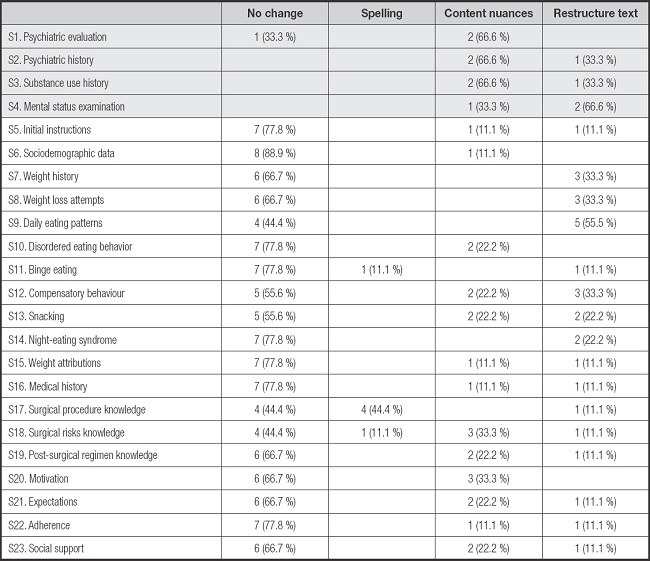

In the qualitative evaluation (Table IV), the comments offered were grouped into 4 categories: no modifications, spelling errors found, suggestions for improved wording without altering the original meaning of the text, and comments that questioned the original question by proposing changes in question meaning.

Table IV. Clarification from experts (n = 3 for S1 to S4 for highlighted results, n = 9 for the rest).

Section 4, on the collection of background information and psychopathological examination, showed the highest level of dissatisfaction (66 % of the raters asked for greater detail), followed in this case by section 9, which was concerned with daily food intake (55 % of raters suggested more detail).

RESULTS OF PATIENT ASSESSMENTS AFTER EVALUATION WITH BIBS

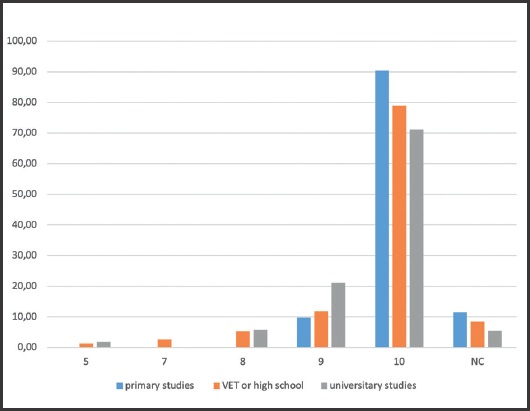

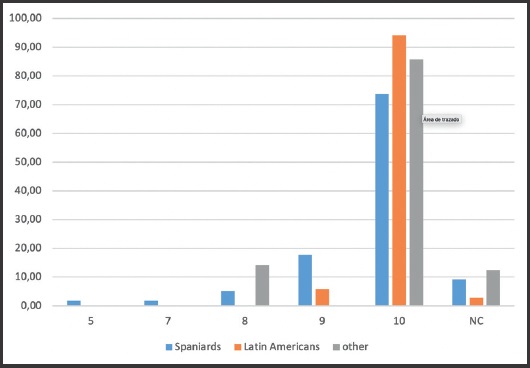

As interviews were conducted, no difficulties in comprehension were evident. The items were clear and understandable for patients. A total of 148 patients (93.1 %) responded with a score of 9 or 10 (with 10 representing “highly satisfied”) on the interview assessment. The median of the evaluations (p50) in both the Hispanic and Spanish populations did not differ, with the score obtained being 10 (10; 10).

The survey was equally well rated among the population with different levels of education (100 % with primary education, 90.79 % with VET or high school, 92.31 % with university studies), as well as among the people coming from Latin America (100 % rated 9 or 10) and the native Spanish population (91.53 % rated 9 or 10) (Fig. 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Relative frequencies of ratings by language (n = 173). Ratings from 0 to 10 (0-deficient to 10-excellent).

DISCUSSION

Adapting a semi-structured interview to another language may seem a simple process but it is complex, not only because of the difficulties inherent in translation (32) but also because once it has been translated, it is difficult to objectively check that it has been done properly and that the properties of the original instrument are maintained. Unlike what happens with questionnaires or scales, in which the psychometric properties of the instrument can be evaluated once it has been translated and adapted, with a semi-structured interview there are no objective values that allow comparison of the original and translated versions. Furthermore, systematic reviews highlight the scarcity of psychometric assessment instruments for people seeking MBS (33) that can serve as valid comparators.

Two questionnaires, the Bariatric Interprofessional Psychosocial Assessment Suitability Scale (BIPASS) (13) and the Revised Master Questionnaire (MQR) (34), have been developed to assist in the assessment of people seeking MBS, but neither of them has a validated Spanish version. The aim of a psychosocial assessment interview of people seeking MBS is not a numerical output, but guiding a conversation to observe the strengths or difficulties in coping with post-surgical requirements as well as determining the degree of mental health support that is required (20,35,36). Validating a translation means establishing that both versions, translated and original, are equivalent not only in semantic terms, that is, in conveying the original idea, but also in their conceptual equivalence and in their applicability to individuals in their respective cultures (32).

To translate the BIBS, it was decided to adopt the previously described translation-back-translation method (25-27), although some authors such as Walde and Wölm recommend the use of the TRAPD method: “Translation, Review, Adjudication, Pretest and Documentation” (37). The TRAPD method advocates evaluating the questionnaire in the target population rather than comparing the original and back-translated versions, as they argue that such a comparison provides only limited and potentially misleading information about the quality of the text in the target language (32,37). In our case, and given that it is not possible to easily evaluate the BIBS, the back-translation method was considered more appropriate as it allowed us to confirm with the original authors that the translation maintained its original meaning. However, as Kristjansson et al. point out, back-translation, while allowing semantic equivalence to be determined, does not guarantee conceptual equivalence or cultural fit (32). Therefore, as the interview is utilized by practitioners, qualitative validation using expert judgement was considered necessary. Expert judgement has been used in research to validate an instrument subjected to translation and standardization procedures in order to adapt it to different cultural meanings (38 39-40).

In relation to the methods for collecting the information provided by experts, it was decided to use the Delphi method (29), a technique that offers a high level of interaction between experts through an iterative process, while allowing anonymity and the use of virtual technology, bridging geographical distances. The Delphi technique incorporates the use of an anonymous questionnaire that is answered autonomously, but sharing decisions through the researcher, who aggregates the opinions provided.

The selection of the number of experts depends on aspects such as ease of access to them or the possibility of knowing enough experts on the subject matter of the research (39). Finding mental health experts trained in the assessment of people seeking MBS in Spain was complex as there is no formal/recognized area of specialization in this field. Therefore, a multidisciplinary group of experts was selected that included mental health professionals who had experience or regularly performed this task, endocrinologists with expertise in nutrition, and surgeons specialized in metabolic surgery. Only sections 1 to 4 (psychiatric assessment and history, including personal psychiatric and substance use history) were exclusively assessed by mental health professionals.

The difficulty in finding mental health experts in the field of metabolic surgery, on the other hand, highlights the need for training and also the need for a semi-structured interview that can help mental health professionals to understand which aspects are relevant during this type of interview, facilitating a greater identification and standardization of criteria.

In the qualitative assessment (Table IV), most of the comments offered were in relation to the lowest-rated sections, those relating to the psychopathological examination and general clinical history taking (Section 4), which is generally carried out in the initial assessment. This section is less detailed in the original English version of the BIBS as it is expected that the mental health clinician has training in administering a general mental health evaluation, and therefore it is left to the expertise of the assessing professional. They were also rated lowest by the experts both in terms of clarity of wording and cultural adaptation. Almost all comments offered in the qualitative assessment in Section 9, referring to daily eating patterns, were reviewed and introduced in the definitive translated version. The rest of the results obtained from the group of experts were favorable, with consensus among most experts, who were satisfied with the translation, confirming that the equivalence between the original meaning and the Spanish translation had been achieved. Moreover, it was well accepted by the majority of the 173 patients seeking MBS who were evaluated using the translated version of BIBS, thus proving its acceptability.

Although the interview translation was designed with the Spanish population in mind, no differences were found between the ratings of the interviews conducted with Latin Americans (p50, 10), nor were there any difficulties in their comprehension. However, given that the experts who were asked to evaluate this came from Spain, it would be advisable to test its fit in populations in which the evaluators are Latin Americans.

Despite its limitations, such as the difficulty in finding experts and the need to extend its validation to mental health professionals from Latin America, this study represents a significant advance in the psychosocial assessment of people seeking MBS, as it is the first work to propose the cultural adaptation and translation of BIBS into Spanish. To date, no other instruments in Spanish could guide a multidimensional assessment of people seeking MBS. It is also an aim of this study to propose a method for translating into other languages semi-structured interviews for which there is no gold standard.

In the future, it will be necessary to implement our knowledge of the factors that worsen post-surgical prognosis, and to develop instruments to identify patients at higher risk of unfavorable outcome after surgery, thus facilitating appropriate and efficient interventions. Future research could also adapt the BIBS to other Spanish-speaking populations.