INTRODUCTION

Four years ago, a global pandemic occurred and to this day its consequences continue to be studied not only at the respiratory level, but also in various aspects related to lifestyle. In December 2019, the first case of COVID-19 was identified in Wuhan, China. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization recognized the widespread global transmission of COVID-19 and declared it a pandemic, which constituted a global emergency with a high impact on public health (1,2). The first case was detected in Mexico on February 27, 2020 at the National Institute of Respiratory Diseases in Mexico City, and the first death occurred on March 18. On March 24, with 475 confirmed cases, Phase 2 of the “health contingency” was declared with stricter measures of social distancing, confinement and academic restriction (3).

As a result of this situation, educational institutions were required to substitute in-person teaching for virtuality to put social distancing into practice and reduce contagion during the COVID-19 pandemic (4). This social distancing affected a large number of children, adolescents, adults and the elderly in mental health for months or years during and after the pandemic. Various studies mentioned an increase in symptoms of depression and anxiety, post-traumatic stress, suicidal ideation, as well as sleep problems in these populations (1,5).

One of the groups that was identified as most vulnerable to the situation of voluntary confinement were adolescents; this population showed higher levels of depression, stress and anxiety (6). Some research mention that preventing adolescents from interacting and engaging socially with their peers and educators, the prolonged periods of school closures, and the restriction of movement were manifested as emotional restlessness and additional anxiety (7).

On the other hand, there are reports that indicate that some of the direct psychological effects of COVID-19 among children and adolescents included: sleep and appetite disorders, learning difficulties, hyperactivity and irritability. In schoolchildren, distress symptoms such as palpitations, hyperventilation and diarrhea appeared, generally associated with somatization processes; additionally, signs of depression were manifested with feelings of sadness and abandonment.

In the behavioral aspect, emotional and behavioral regressions have been mentioned and described more frequently in preschoolers and young school children, but they also occurred in adolescents. The psychological effects derived from the infectious disease and confinement have lasted beyond their duration (8).

Ochoa et al. (9), in their research, which included cross-sectional longitudinal studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses, reported that the prevalence of stress in children and adolescents aged 2 to 17 years during the pandemic ranged between 28 % and 34 %. Furthermore, the prevalence of emotional and behavioral problems was 17.6 % (18.6 % for boys and 16.6 % for girls). The prevalence of mild to severe anxiety and depression symptoms was high (37.4% and 43.7 %, respectively).

It is important to mention that psychological alterations such as anxiety and depression may be closely related to risky eating behaviors (REB) (10). In Spain, Samatán and Ruiz (11) reinforce this idea in their study performed with adolescents under 18 years of age who attended the Eating Disorders Unit for the first time, reporting that the adolescent population was the most affected age group (87.1 %), compared to 12.9 % of those under 13 years of age, with a greater contrast between these groups during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Mexico, Villalobos-Hernández et al. (12) reported the prevalence of REB in Mexican adolescents, based on the results of the National Continuous Health and Nutrition Survey 2022 (ENSANUT): 6.6 % of adolescents presented some degree of REB (5.0 % moderate risk and 1.6 % high risk). These data were similar to those reported in the ENSANUT 2018-2019, in which 7.3 % of adolescents presented some degree of risky eating behaviors, but higher than the prevalence reported in the ENSANUT 2006 (3.9 %), in which the same questionnaire was used to detect REB at the national level before pandemic. Likewise, it was reported that adolescent women were at greater risk and people residing in rural areas at lower risk of suffering from this problem. Derived from these data, the authors (12,13) pointed out the importance of continuing to monitor REBs in national representative surveys, since this problem may lead to negative health repercussions in this population.

Previous studies have identified associations of some psycho-emotional and anthropometric variables with REBs. Radilla et al. (14) conducted a 3-year study prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which was a randomized controlled trial with an educational intervention to improve eating habits and physical activity. The research was performed in 16 Technical Secondary Schools in Mexico City and involved 2,368 adolescents with the purpose of identifying risk or protective factors of suffering from REB. According to the results, depression and anxiety, as well as being a woman and having a higher body mass index (BMI) were risk factors of suffering from REB, while physical activity measured by the number of steps was a protective factor.

Eating behavior is a human activity related to food intake and depends on internal and external factors of the individual. It has been reported that during confinement, there were changes in the total amount of consumed foods, especially an increase in sweet and salty foods with high energy density. At the same time, there was a decrease in the consumption of vegetables, fruits, and legumes (15 16-17).

Taking the above into account, the purpose of this research was to evaluate symptoms of anxiety and depression, REB, eating habits and physical activity after the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexican secondary school adolescents, as well as identify associations between study variables and REB.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

An observational, quantitative and descriptive study was performed. In 2022 (transition period after the pandemic), 2,710 first-grade secondary school students were evaluated, with an average age of 12 years, from 33 secondary schools in 12 municipalities in Mexico City.

As inclusion criteria, full-time technical secondary schools were considered, which provided letter of informed consent from participants signed by their parents or guardians and who gave their assent to participate. Students with a diagnosis of diabetes, hypertension, metabolic syndrome and other chronic diseases, who were pregnant or lactating at the time of the intervention, students with acute illnesses and those who did not have authorization or did not want to participate were considered exclusion criteria. The elimination criteria were those students who refused to participate in any component of the study.

Body composition measurements were taken and questionnaires were applied to evaluate symptoms of anxiety and depression, REB, eating habits and physical activity.

ANTHROPOMETRIC EVALUATION

Prior to the application of the questionnaires, anthropometric measurements were taken with the use of an Inbody-270 body composition analyzer (South Korea), and weight status was estimated with the body mass index (BMI) percentiles, proposed by the WHO (18) by using the Who Anthro Plus® program (Switzerland).

INSTRUMENTS

With the purpose of evaluating symptoms of anxiety and depression, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-HADS, validated in a Mexican population between 12 and 68 years old with eating disorders, were used; Cronbach’s alpha of the total scale was 0.88 and of its two subscales > 0.80 (19,20). The scale is self-reported and allows to identify symptoms of anxiety and depression. It consists of fourteen multiple-choice items and two subscales: depression and anxiety, each with seven items. The score for each subscale can vary between 0 and 21, each item presents four response options, ranging from absence or minimal presence = 0 to maximum presence of symptoms = 3. The higher the score obtained from each subscale the greater the intensity or severity of symptoms: 0-7 points absence of symptoms; 8-10 presence of symptoms; 11-21 complete clinical picture.

To evaluate risky eating behaviors (REB), the questionnaire of Unikel et al. (21) was applied, validated in Mexico, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83. The questionnaire is self-reported and easy to apply; it has been used in the ENSANUT 2006, 2012 and 2022 national surveys to evaluate REB in Mexican adolescents (12,13). The questionnaire was developed based on the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-IV and consisted of questions with a Likert scale with four response options: never = 0, sometimes = 1, frequently (twice a week) = 2, very frequently (more than twice a week) = 3, with a cut-off point < 7 no risk, between 7 and 10, moderate risk, and greater than 10 points, high risk. The instrument evaluates the main behaviors that resulted in weight loss over the previous three months, such as: concern about gaining weight, binge eating, the feeling of lack of control when eating, restrictive eating behaviors (diet, fasting, excessive physical activity, and use of weight-loss pills), as well as purgative behavior (self-induced vomiting, use of laxatives, and diuretics).

A self-report questionnaire on eating habits and physical activity was applied, consisting of 31 items, which included the following variables: frequencies of meal times, physical activity and lifestyles, consumption of high-calorie foods, company in food consumption, consumption of vegetables and fruits, place of food consumption, consumption of alcoholic beverages, sugary drinks, plain water and milk, Cronbach’s alpha of the total questionnaire was 0.78 (22).

Likewise, eating habits were assessed by self-reported surveys, using 24-hour recall, in which adolescents described in detail at-home measurements of all foods and beverages consumed the previous day. The obtained information was compared with the energy and nutrient reference values of the Mexican System of Equivalent Foods (23) with the purpose of knowing whether the adolescents’ diet corresponds to their weight, height, age, and physiological situation.

SAMPLE SIZE

The sample size was established using a base of 119 schools from 16 municipalities in CDMX, of which 46 secondary schools were extended-time schools and therefore met the characteristics required for the intervention during the 2022 school year.

The selection was adjusted to simple random sampling with a finite population and the Murray and Larry formula (24) was used for the calculation: where: n: sample size. N: population size, the value of 46 was used (full-time secondary schools). Z: value corresponding to the approximately normal distribution, Zα = 1.62; α = 0.10. p: expected prevalence of the parameter to be evaluated, if unknown (p = 0.5), which increases the sample size. Q: 1 – p (if p = 50 %, then q = 50 %). i: assumed error (10 %).

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

All adolescents participated voluntarily, had the informed consent of their parents or guardians and verbal assent prior to participation. The present study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Division of Biological and Health Sciences. The Divisional Council of Biological and Health Sciences of the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Unidad Xochimilco, in session 7/21, held on May 6, 2021 through Agreement 7/21.5.4 of document DCBS.CD.157.21 issued the resolution to approve the research project.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

To analyze the sociodemographic data, descriptive statistics were applied with measures of central tendency and dispersion. The average frequency and percentage of data such as age, sex, frequency of food consumption, and results of the questionnaires applied were obtained. Likewise, in order to identify associations with REB in Mexican adolescents, a binomial logistic regression analysis was carried out on all measurements, which were contrasted with the dependent variable (occurrence of REB). The data obtained were analyzed with the SPSS statistical package, version 24.0 for Windows.

RESULTS

From the total of 2,710 students, 1,430 (52.8 %) were female and 1,280 (47.2 %) were male, with an average age of 12 years.

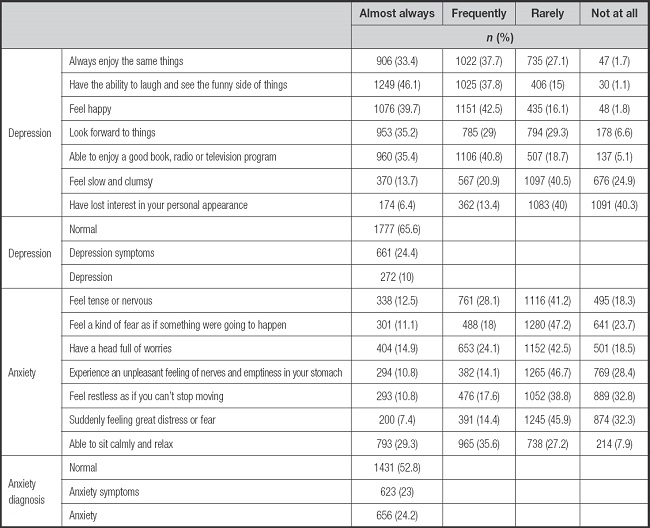

Table I shows the psychological aspects of the adolescents: 34.4 % of them presented symptoms of depression (24.4 % moderate symptoms and 10 % maximum symptoms) and 47.2 % of adolescents presented anxiety symptoms (23 % moderate and 24.2 % maximum symptoms).

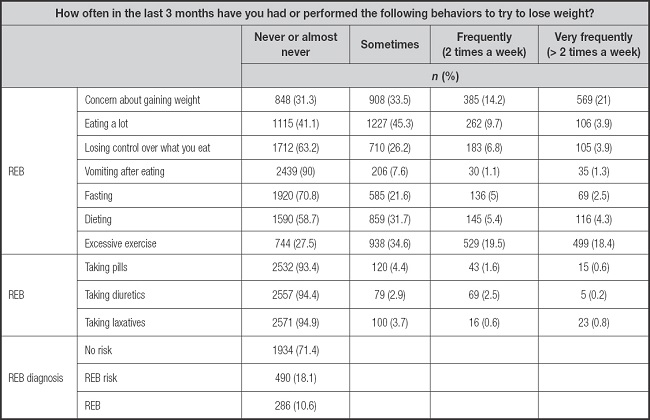

With respect to REB, it was observed that the category with the highest incident rate was the practice of excessive exercise to lose weight (37.9 %), followed by concern about gaining weight (35.2 %), eating too much (13.6 %) and dieting to lose weight (9.7 %), with a frequency of at least twice a week. When evaluating REB in total, it was observed that 18.1 % of the adolescents were at moderate risk and 10.6 % at high risk of developing unhealthy behaviors (Table II).

When analyzing the nutritional status of the participants, it was observed that 2,296 (84.7 %) adolescents had an appropriate height for their age, 373 (13.8 %) were at risk of having short height and 41 (1.5 %) had low height for their age. Likewise, 1,264 (46.6 %) adolescents had an adequate weight, 719 (26.5 %) were overweight, 543 (20 %) were obese, and 184 (6.8 %) had low weight for their height.

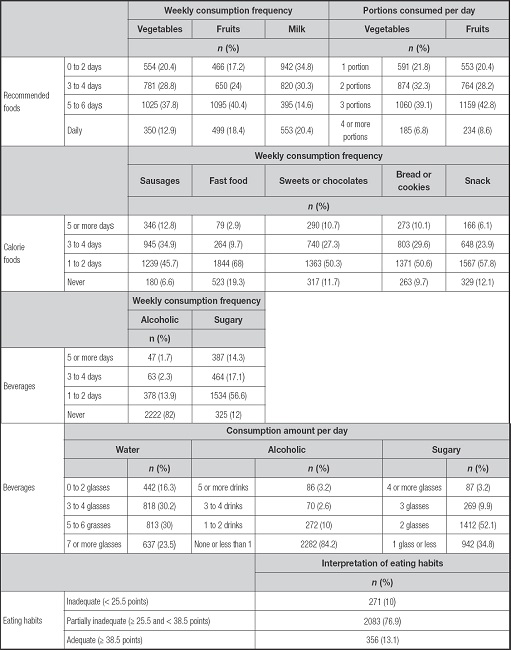

Regarding the eating habits of adolescents (Table III), it was observed that only 12.9 %, 18.4 % and 20.4 % of adolescents consumed vegetables, fruits and milk, respectively on a daily basis. Regarding the consumption of foods with high energy density, it was found that adolescents consumed sausages (47.7 %), fast food (12.6 %), sweets or chocolates (38 %), bread or cookies (39.7 %) and snacks (30 %) three or more times a week. Likewise, 1.7 % of adolescents reported consuming alcoholic beverages 5 or more times per week and 31.4 % of adolescents consumed drinks with added sugars three or more times per week. On the other hand, only 23.5 % of adolescents consumed seven or more glasses of plain water per day. When analyzing the food and drink consumption of adolescents in total, it was found that only 13.1 % had adequate eating habits.

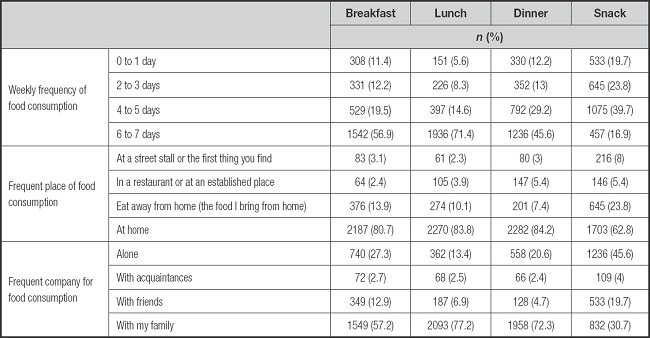

When investigating the frequency of consumption of main meals (Table IV), it was observed that only 56.9 % eat breakfast, 71.4 % eat lunch and 45.6 % have dinner six or seven days a week. Most adolescents ate their meals at home, generally accompanied by their family, although 45.6 % of adolescents reported snacking alone.

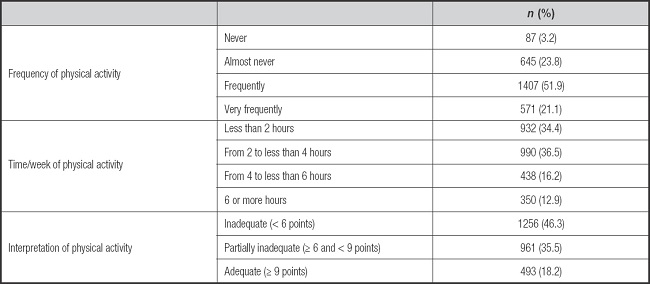

Regarding physical activity (Table V), it was reported that 27 % of adolescents never or almost never do physical activity and 34.4 % do less than two hours a week. When analyzing together the frequency and time of physical activity performed by adolescents, only a low percentage (18.2 %) of them complied with adequate physical activity practice.

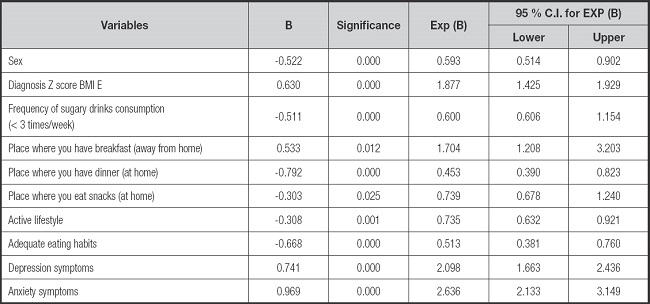

In the Multivariate Binary Logistic Regression analysis to identify associations between REB and study variables (Table VI), it was found that symptoms of depression (OR = 2.098; 95 % CI = 1.663-2.436, p < 0.0001), anxiety (OR = 2.636; 95 % CI = 2.333-3.149, p < 0.0001), higher BMI (OR = 1.877, 95 % CI = 1.425-1.929, p < 0.0001), as well as eating breakfast outside the home (OR = 1.704, 95 % CI = 1.208-3.203, p = 0.012) increase the probability of presenting REB. Otherwise, a negative association was observed between REB and variables such as being male (p < 0.0001), consumption of sugary drinks < 3 times/week (p < 0.0001), having dinner at home (p < 0.0001), eating snacks at home (p = 0.25), active lifestyle and appropriate eating habits (p < 0.0001).

Tabla VI. Associations between study variables and risky eating behaviors (REB)* in adolescents.

Risky Eating Behavior Questionnaire (CAR) that has a Likert scale with four response options: never = 0, sometimes = 1, frequently (twice a week) = 2, very frequently (more than twice a week) = 3, with a cut-off point < 7 no risk, between 7 and 10 moderate risk, and greater than 10 points high risk.

DISCUSSION

Based on the analysis of the results with 2,710 adolescents from Mexico City, it was possible to identify the symptoms of anxiety and depression, risky eating behaviors, eating habits and physical activity that this population had during and after the COVID-19 pandemic; it was also possible to identify the associations between study variables and the development of risky eating behaviors.

In this research, it was found that a high number of adolescents presented symptoms of depression (34.4 %) and anxiety (47.2 %). These data coincide with research performed on children and adolescents during the pandemic: in Honduras, some degree of depression (62 %), anxiety (55.9 %) and stress (55.2 %) was reported in the majority of participants (1); in Spain, emotional symptoms and behavioral problems were observed in 69.7 % and in English-speaking populations, symptoms of depression and anxiety were observed in 43.7 % and 37.4 % of participants, respectively (6,9). Angeles and Mazon (25) indicated that during confinement and the year of epidemiological transition, the lack of a varied routine, physical exercise, recreation, seeing friends, going to the park or visiting other family members without restrictions were relevant factors that affected the psychological health of individuals. It is necessary to consider that prolonged boredom or even experiencing different types of domestic violence could also be factors that affected the mental health of adolescents.

Regarding eating behaviors, the results of the present study showed that one in ten adolescents presented a high risk of developing REB, which was higher than the prevalence reported at the national surveys (ENSANUT) performed previously (3.9 %) and during the pandemic (6.6 %) (12,13). The increase in REB during the years of confinement may be explained by changes in daily routine, increase in symptoms of depression and anxiety, as well as changes in eating habits and decrease in physical activity. Our results also confirmed previously reported data; that women have a higher prevalence of REB than men (12,13,26,27). Regarding the sociocultural characteristics that surround adolescents, it is worth mentioning that at the national level, REBs are observed more frequently in adolescents from urban areas (12,13).

In this study, variables such as symptoms of anxiety and depression, female sex, higher BMI, and eating breakfast outside the home were positively associated with REB. Otherwise, negative associations were observed between REB and variables such as consumption of sugary drinks < 3 times/week, having dinner and snacks at home, active lifestyle and appropriate eating habits. These results coincide with the study by Quiñones et al. (28) performed with 916 adolescents in Peru, in which a higher prevalence of eating disorders was found in female adolescents, as well as in participants who had symptoms of anxiety. According to Canals and Arija (29), generalized anxiety detected in childhood may predict the manifestations of REB and the diagnosis of eating disorders in adolescence. At later ages, anxiety may be considered a risk factor for the development of eating disorders in women but not in men.

Likewise, in the present study, a high prevalence of overweight and obesity was found (combined prevalence 46.5 %, overweight 26.5 %, obesity 20 %), similar to results reported during the pandemic by the ENSANUT Continua 2020-2022 (a combined prevalence of 41.1 %, of which 23.9 % of participants were overweight and 17.2 % were obese) with a sample of 5,421 that represents 17,168,295 Mexican adolescents between 12 and 19 years old (30). This prevalence was higher compared to those reported in national surveys prior to the pandemic: in Mexico, from 2006 to 2018, the combined prevalence of overweight and obesity in adolescents increased from 33.2 % to 38 %, respectively (31).

According to Medina Zacarias et al., 2020 (31), the most important risk factors associated with overweight/obesity in Mexican adolescents were related to family coexistence factors (e.g., living with an overweight adult) and lifestyle factors (spending > 2 hours in front of a screen and having a dietary pattern characterized by sugary drinks, sweets, sweet cereals, desserts, and snacks consumption). Being overweight since childhood and adolescence implies the appearance of chronic diseases from the earliest ages, which results in lower quality of life, loss of productive years and increase in health expenses at the level of the family and the health sector. In addition, children and adolescents with obesity were at greater risk of developing more severe SARS-CoV-2 disease (COVID-19), as well as the multisystem inflammatory syndrome caused by this virus (32).

Furthermore, in the present study, unhealthy lifestyles were observed among the participants: 86.9 % of the adolescents had inadequate or partially inadequate eating habits and 81.8 % presented inadequate or partially inadequate physical activity, results that coincide with those reported by Navarro et al. (33), who in a study involving 470 Mexican adolescents, found that 74.3 % of the participants obtained a low level of physical activity and 54.6 % had unhealthy eating habits. Our results and the study by Navarro (33) have in common the fact that confinement in this population was characterized by changing the routine of individual and family habits. The interruption of in-person school activity was one of the factors that most modified the behavior of the young population. Increased sedentary lifestyle with the development of bad eating habits led to the use of electronic devices, as well as excessive use of social networks and streaming platforms, accompanied by a feeling of boredom and frustration (34).

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

Among the limitations of the study was its cross-sectional design, which does not allow causal interpretation of the associations identified by the statistical models. Additionally, self-reported questionnaires were administered, which are susceptible to response bias. The questionnaires applied to the sample to evaluate anxiety, depression, and risky eating behaviors identified symptoms and tendencies toward risky behaviors, but did not diagnose any clinical condition. However, the instruments applied in the present study have been previously validated in different population groups, including Mexican adolescents with eating disorders, and have been frequently used to identify unhealthy behaviors in national surveys.

It was concluded that confinement wreaked chaos on the lifestyle of Mexican adolescents and their psychological health, demonstrating an association between REB and variables such as female sex, higher BMI, consumption of beverages with added sugars, eating outside the home, and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Therefore, it is important to develop interdisciplinary targeted and coordinated prevention programs for depression, anxiety, and eating disorders to reduce psychological risk factors resulting from social isolation, as well as promote a healthy lifestyle.