Introduction

Bullying behavior maintains the attention of researchers due to its relationship with the development of antisocial behavior, drug use (Cerezo & Mendez, 2012; Garaigordobil, 2017; Sigurdsona, Wallander & Sunda, 2014), use of weapons (Valdebenito, Ttofi, Eisner & Gaffney, 2017), and their association to public health problems such as anxiety, depression, mental problems (AlBuhairan, et al., 2017).

The study of bullying from an ecological perspective allows to have a broad vision of the phenomenon by identifying individual, family, school and cultural risk factors (Postigo, González, Montoya, & Ordoñez, 2013). This perspective has been used in the study of socially relevant variables, highlighting the need to study a social phenomenon in the cultural framework due to interaction with the environment (Caicedo & Jones, 2014; Torrico, Santín, Andrés, Menéndez & López, 2002).

The study of the micro family system, describes that students at greatest risk of participating in bulling, live in dysfunctional family contexts, which are characterized by resolving conflicts with aggression, communication deficits, getting involved affectively little, without supporting each other (Eşkisu, 2014; Lereya & Wolke 2013), describing that parents of bullying students use ineffective parenting practices characterized by the use of aggression, overprotection and lack of monitoring (Cook, Williams, Guerra, Kim & Sadek, 2010; Lereya, Copeland, Costello & Wolke, 2015; Mendoza, 2017a). Demonstrating that parents do not establish communication with school authorities (Mendoza & Barrera, 2018).

The influence of the social context (macrosystem) has been studied by identifying that the conflict by arming, socioeconomic conditions, in combination with a violent neighborhood predict bullying (Chaux, Molano & Podlesky, 2009). Other social factors such as traditional gender stereotypes (machismo and traditional female stereotype) have demonstrated their association with bullying, knowing that machismo predicts participation in bullying with bully role and the double role: victim/bully, (Navarro, Larrañaga & Yubero, 2016; Morales, Yubero & Larrañaga, 2016), and the traditional female stereotype is related to victimization (Navarro, et al., 2016).

The study of bullying from an ecological perspective, has allowed to describe it, and identify multicausal causes of its development, which guide effective programs for its prevention and intervention (Cerezo & Ato, 2010; Cerezo, Sánchez, Ruiz & Arense, 2015; Mendoza, Cervantes & Pedroza, 2016; Mendoza, Morales & Arriaga, 2015). Under this line of study has been identified a student called not involved, because he does not participate as a bystander, victim, bully and also with the double role, is the one with the greatest representative among the students according to different studies (Elgar, et. al., 2015), has been little studied, however, his study will provide valuable information about the factors that protect him from participating in school violence or bullying.

The study of bullying is especially necessary in violent societies such as Mexico, in which an estimated 170,000 thousand people are killed by organized crime and more than 28,000 people disappeared between 2006 and 2016, (BBC News World, 2018), a Country in which children and young people are invited to be part of criminal groups, and in which 69% of young people who use weapons in violent acts, have no consequences on the part of their families and also by the local police (Institute for Economics and Peace, 2018).

Therefore, the general objective of this research is to identify the characteristics of the students "Not involved" in bullying episodes, based on the variables: gender stereotypes, parenting styles, attitudes and social cognitive strategies, and food over-intake.

Method

Participants

1190 basic education students participated, enrolled in eleven public schools in the State of Mexico (six high schools and five elementary schools), 616 were high school students students in the three grades (318 women, 298 boys) 574 were elementary school pupils who were in third to sixth grade of primary school (281 girls and 283 boys). Participants were between 8 and 16 years old (11.4; 1.78). Participants were selected from a non-random incidental sampling referred to as mixed, the above because the schools were chosen for accessibility through the signing of an agreement with municipal government, it is called mixed since although the schools were not chosen at random, the groups of participating were chosen at random (Sáez, 2017).

Instruments

Five instruments measuring the variables were used, each of which is specified below.

Bullying Questionnaire (Mendoza, Cervantes, Pedroza & Aguilera, 2015).

The questionnaire measures how often, students direct aggression towards their peers (violence and bullying), are victims, bully, or bystander of them. It consists of 40 items, with three scales: victim scale with twenty items (α = 90), bully scale with twenty items (α = .89), bystander scale with twenty items (α = .92).

The answers are chosen in four levels of measurement (likert), which indicate how often they receive, observe, or exert some kind of aggression toward their peers. (Every day; two or three times a week; two or three times per month; it has not happened). The Cronbach Alpha of this instrument is .95.

Personal Attributes Questionnaire (PAQ, Spence & Helmreich, 1978; validated in Spanish, Mendoza, 2006), consisting of 24 items, measures the degree by which a person identifies with female, male, and combination of both (androgyny), with total alpha of cronbach .80.

Female Scale, measures identification with the traditional female stereotype (emotional, warm, ability to dedicate to others, affectionate, helpful to others, friendly, identifies feelings of others, perceives understanding of others), (α = 80).

Female-male scale (Androgynous), measures the identification with the attributes of women and men, without stereotyping towards one in particular (dominant, easily crying, hurting me easily, needing to feel protected, need for approval of others, focused on relationships away from home, independent), (α = .81).

Male scale, measures identification with the traditional male stereotype: macho (independent, superiority, active, competitive, making decisions, does not give up easily, self-confident, does not give up under pressure), (α = .80).

Food Overintake Questionnaire (OQ) (O'Donell & Warren, 2007), measures habits, thoughts and attitudes related to food over-intake, consists of 80 items, has a Likert scale of five levels: nothing, little, moderately, quite, very much, α = .91. It is integrated by two factors a) Habits and attitudes related to eating behavior (over-intake, sub-intake, food cravings, rationalizations, motivation for weight loss, expectations related to eating), α = .90, and b) General health habits and psychosocial functioning (Health habits, Body image, Social isolation, Affective disturbance), α = .89.

Attitudes and Cognitive Social Strategies Questionnaire (Moraleda, González, & García-Gallo, 1998), evaluates social competence, through the ease or difficulty to adapt to the social context, consists of 137 items (α = .95), and have two factors: Social Attitude Scale (α = .92) and Social Thought (α = .95), (Mendoza & Maldonado, 2017).

Social Attitude Scale, measures the ease in social interaction: Conformity with the socially correct; social sensitivity or empathy; help and collaboration; security and firmness in the interaction; prosocial leadership, aggressiveness-stubbornness; dominance, apathy and withdrawal; anxiety and shyness.

Social Thought Scale, evaluates cognitive skills that facilitate or not a social relationship, measures impulsivity; independence; convergence; perception and expectations about the social relationship; leadership and acceptance by their parents; ability to observe and retain relevant information about social situations; perception of social situations; ability to solve social problems; ability to anticipate consequences for social behavior, and choose appropriate solutions for social behavior.

Parenting Practices questionnaire (Mendoza, 2018), is a questionnaire answered by children and adolescents to identify the discipline behaviors of their parents, they are composed of 32 items, α= .83. It has a likert scale of four levels: every day, two or three times a week; two or three times a month; hasn't happened in the last two months. It has six factors: Parental abuse (use of physical, verbal, psychological punishment, α = .82); Positive parenting (shows the right way to do things, ignoring inappropriate behavior, rewarding the proper behavior, α = .80); Response cost, the parent requests that he repair the damage he did (α = .81); No leadership, the parent does what the child requests (α = .80); Negative Control, the parent controls the behavior of their children on a daily basis (α = .81); Overprotection, parents solve activities, preventing their children from developing autonomy (dressing them, doing their homework, α = .80).

Type of study and design

Descriptive study, which allowed to specify the characteristics and profiles of groups of students (depending on their participation in episodes of bullying as victims, bully, double role or without getting involved in them) collecting information about study variables (Müggenburg & Pérez, 2007). The study was carried out in a single moment and in a unique time, so its design is transversal.

Procedure

A collaboration agreement of the municipal government was signed with the Faculty of Behavioral Sciences of the Autonomous University of the State of Mexico, with the purpose of developing research in collaboration with authorities. From the signing, a meeting was planned with the managers of the selected educational institutions to share with them the objectives of the research, the instruments, as well as the requirements to develop it. Once the managers accepted, planning of days and times to apply the measuring instruments was done. The administration of the instruments was carried out in two sessions of one hour and thirty each, in classrooms with lighting, ventilation and necessary materials, made by members of the research team trained for administration. Students participated voluntarily, with the authorization of their parents, and were notified about the confidentiality of the information provided. After the information was collected through the questionnaires, the results were returned to each participating school through a ceremony with the presence of the school authorities.

Data Analysis

A database was made in the statistical program SPSS version 21.0., the information was emptied to develop the statistical analyses in compliance with the general objective of study:

First the students were classified according to the roles of participation in school violence and bullying, for this purpose a multivariate analysis, called conglomerate analysis, was developed.

Once students have been classified, the next statistical process was to perform a contrast of means (ANOVA of one factor), having as a factor the conglomerate obtained (classification of students) and as a dependent variable, the variables of the study (gender stereotypes, food over-intake, social cognitive attitudes and strategies; parenting).

In all cases in which the value of p is significant, the effect size calculation was made. The Cohen d statistic is shown, the value d = .20 is considered a small effect, d = .50 medium effect, and d = .80 large effect.

Results

Classification of students according to their participation

To respond to the objective, the roles that students play in situations of school violence and bullying were identified, the multivariate analysis of means k, classifies four groups in the bullying circle and one more of students who do not get involved in situations of bullying and school violence, the means for each of the groups are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 identifies the means of each of the factors as a victim and bully of exclusion severe and extreme aggression, each of the identified clusters is described below.

Victim of school violence: This group consists of 29 students who receive aggression from their peers (extreme aggression, exclusion and severe aggression). Of this group, .8% are women (5 students) and 4% are men (24 students). Girls in this group represent .4% of the total female participants and boys represents 2% of the total male participants. They report being ignored, rejected, speaking ill of them, do not let them participate and receive insults two or three times in the month.

Not involved: This group is made up of 620 students who do not participate as victims or aggressors in situations of school violence or in bullying. Of this group, 52% are women (311 students) and 52% are men (309 students). Girls in the group represent 26% of the total female participants and boys represent 26% of the total male participants.

Bullying victims: This group consists of 158 students, who receive extreme aggression, exclusion and severe aggression. 14% are women (81 students) and 13% are men (77 students). The women in this group represent 7% of the total female participants, men represent 7% of the total male participants. They report being beaten, they hide things, they strike them, they offend or ridicule, pointing out that it happens to them daily (every day; two or three times a week).

Bully: This group is made up of 372 students who direct extreme aggression, exclusion and severe aggression towards their peers. In this group 33% of those involved are women (199 students) and 29% are men (173 students). Girls in this group represent 17% of the total number of women participants and the boys represent 15% of the total male participants. They report directing all kinds of aggressive behavior towards their classmates, such as forcing them to do things they don't want with threats, forcing threats to situations or behaviors of a sexual nature, stealing things from them, intimidating them with phrases or insults of a sexual nature, hitting or threatening to get scary, such behaviors occur daily.

Victim/bully: This group consists of 11 students who, on the one hand, receive extreme aggression, exclusion and severe aggression and at the same time, they direct aggression towards other students. In this group the .5% are women (3 students) and 1% are men (8 students). Girls in this group represent .3% of the total female participants and the boys represent .7% of the total male participants. They are students who direct and receive at the same time extreme aggressive behavior (threatening weapons, threatening sexual situations, forcing them to do things they do not want with threats), exclusion and severe aggression (includes situations such as: rejecting, speaking ill of him or her, insulting him, putting them with nicknames that offend or ridicule him, ignoring him, preventing him from participating, hiding things). They report that episodes occur on a daily basis.

Gender Stereotypes

The results of the ANOVA test, shown in Table 2, indicate statistically significant differences between the groups of student: victims, bully and not involved, based on their identification with male stereotypes traditional, traditional female, and non-stereotypical identification of both behaviors (androgynous). Post Hoc contrast tests show that the students in the group not involved, are those who least identify with the traditional male stereotype, and those who most identify with the androgynous (female-male).

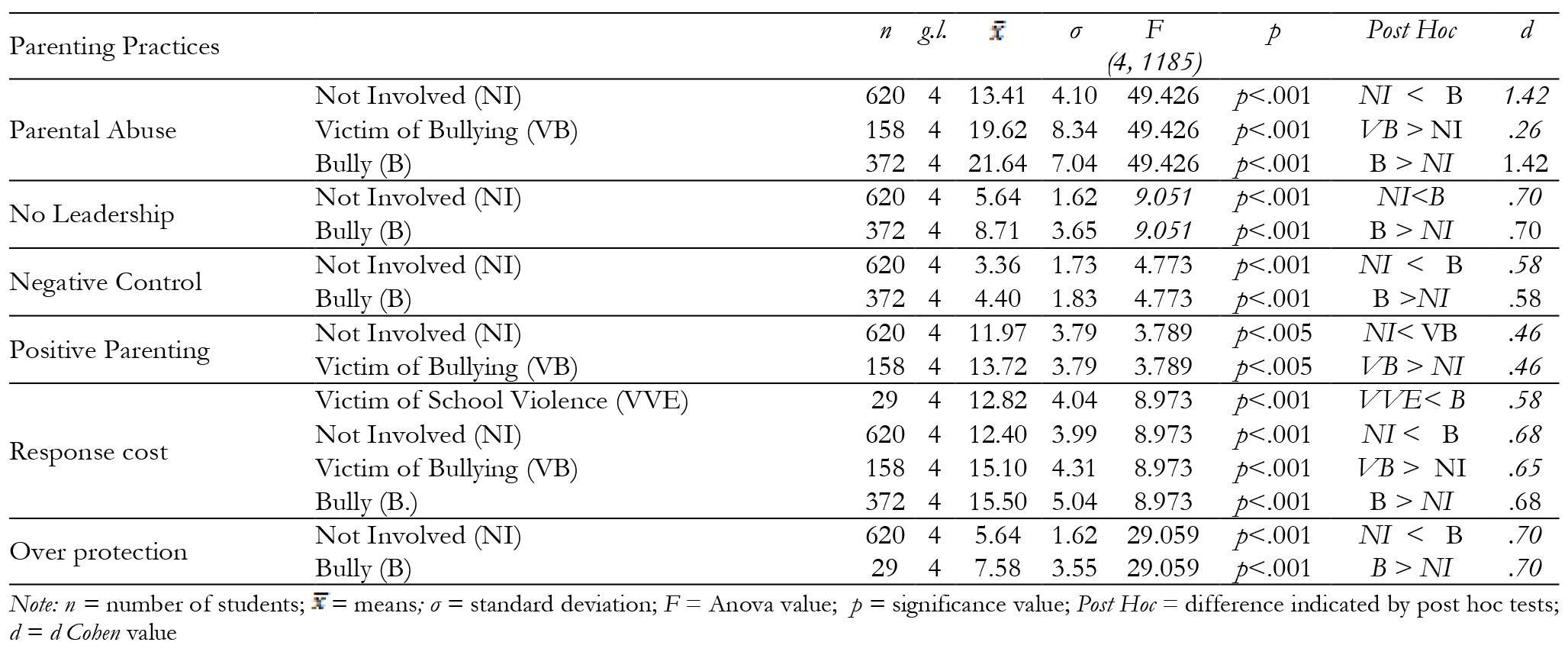

Parenting Practices

With regard to parenting practices used by parents of students who participate in bullying, ANOVA, allows to identify that there are significant differences, Post Hoc contrast tests allow to identify that, students who do not get involved in bullying episodes, have a mean lower than the bully group with respect to: Parental Abuse they receive from their parents, parental overprotection, control, parenting without leadership and cost of response (see table 3).

Social Skills

With respect to the social skills of the students, table 4 shows significant differences in the scale of social attitude of the victim, bully, bully-victim and not involved students, calculated through the ANOVA. Post Hoc contrast tests, indicate that students who are not involved in bullying episodes, have a higher average than the group of students with dual role victim/bully in: Conformity with what is socially correct; Social sensitivity; Help and collaboration; Safety and Firmness in Interaction. Students who do not engage in bullying episodes, who have a higher mean in Leadership, than the bully student group. It is also students who do not participate in bullying episodes (not involved) who exhibit lower mean in aggression-stubbornness, apathy, anxiety and shyness, in contrast to the bully student group (see Table 4).

Table 4. Differences in participation in bullying episodes according to the Social Attitude Scale (Attitudes and Cognitive Social Strategies Questionnaire).

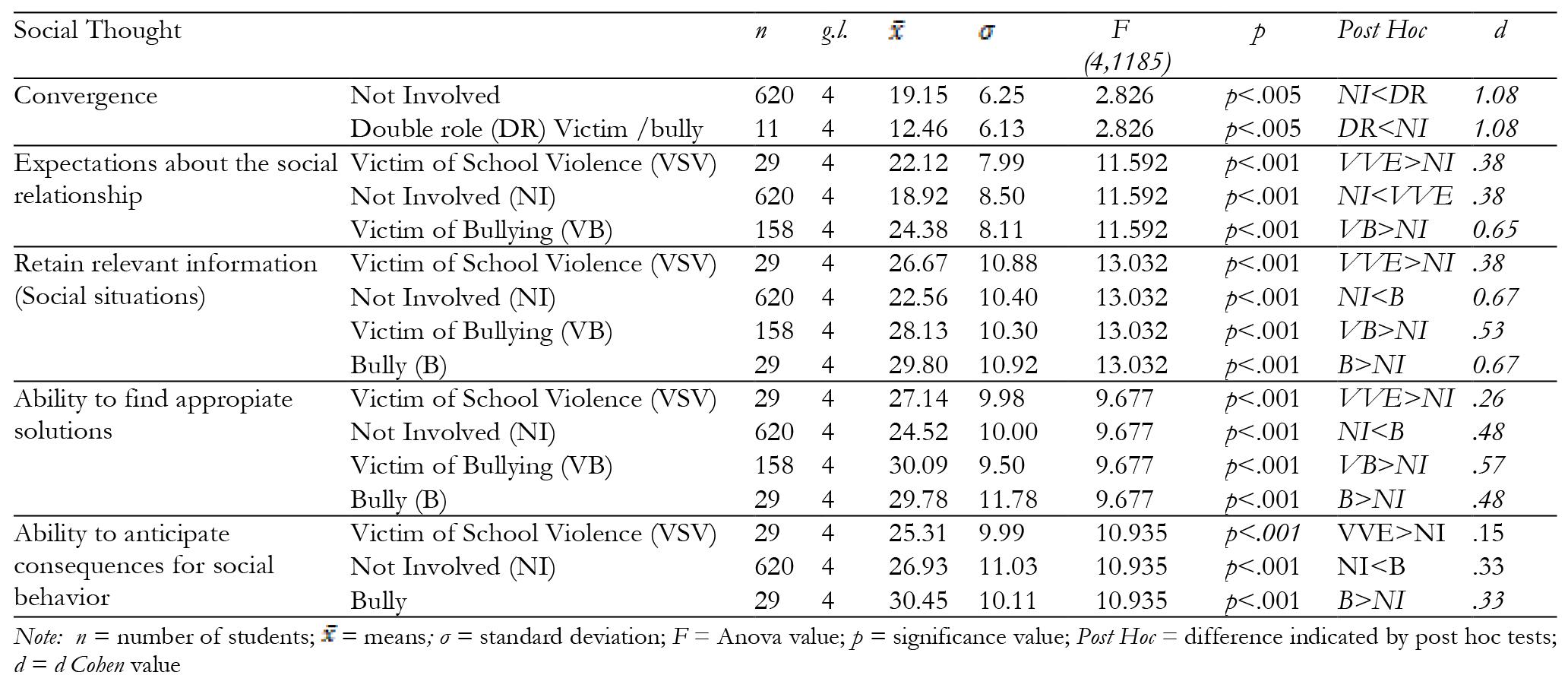

Table 5 shows the results for the Social Thought scale, it should be noted that according to the structure of the instrument it is established that in the sub-scales: Impulsivity; Convergence, Perception of the social relationship, Acceptance of their parents; Observation of social situations; social problem-solving skills; Ability to anticipate consequences; ability to choose appropriate means).

Table 5. Differences in participation in bullying episodes according to the Social Thought Scale (Attitudes and Cognitive Social Strategies Questionnaire).

The results of ANOVA (Table 5) shows significant differences between student groups. The contrast of the Post Hoc tests indicates that the students not involved, have a significantly higher mean, than students with double role victim-bully (in convergence factor). Students not involved have significantly less mean to the bullying victim students in several factors: Perception and expectations about the social relationship; Ability to observe and retain relevant information about social situations; Ability to find alternative solutions to solve social problems; Ability to anticipate and understand consequences of social behavior; Ability to choose appropriate solutions in social behavior (see table 5).

The contrast of the Post Hoc tests indicates that the students named not involved, have a significantly higher mean than the students with double role victim-bully, in: convergence factor. Students not involved have a significantly lower mean than students who are victims of bullying in several factors: Perception and expectations about the social relationship; Ability to observe and retain relevant information about social situations; Ability in the search for alternative solutions to solve social problems; Ability to anticipate and understand social behavioral consequences; Ability to choose appropriate media in social behavior (See table 5).

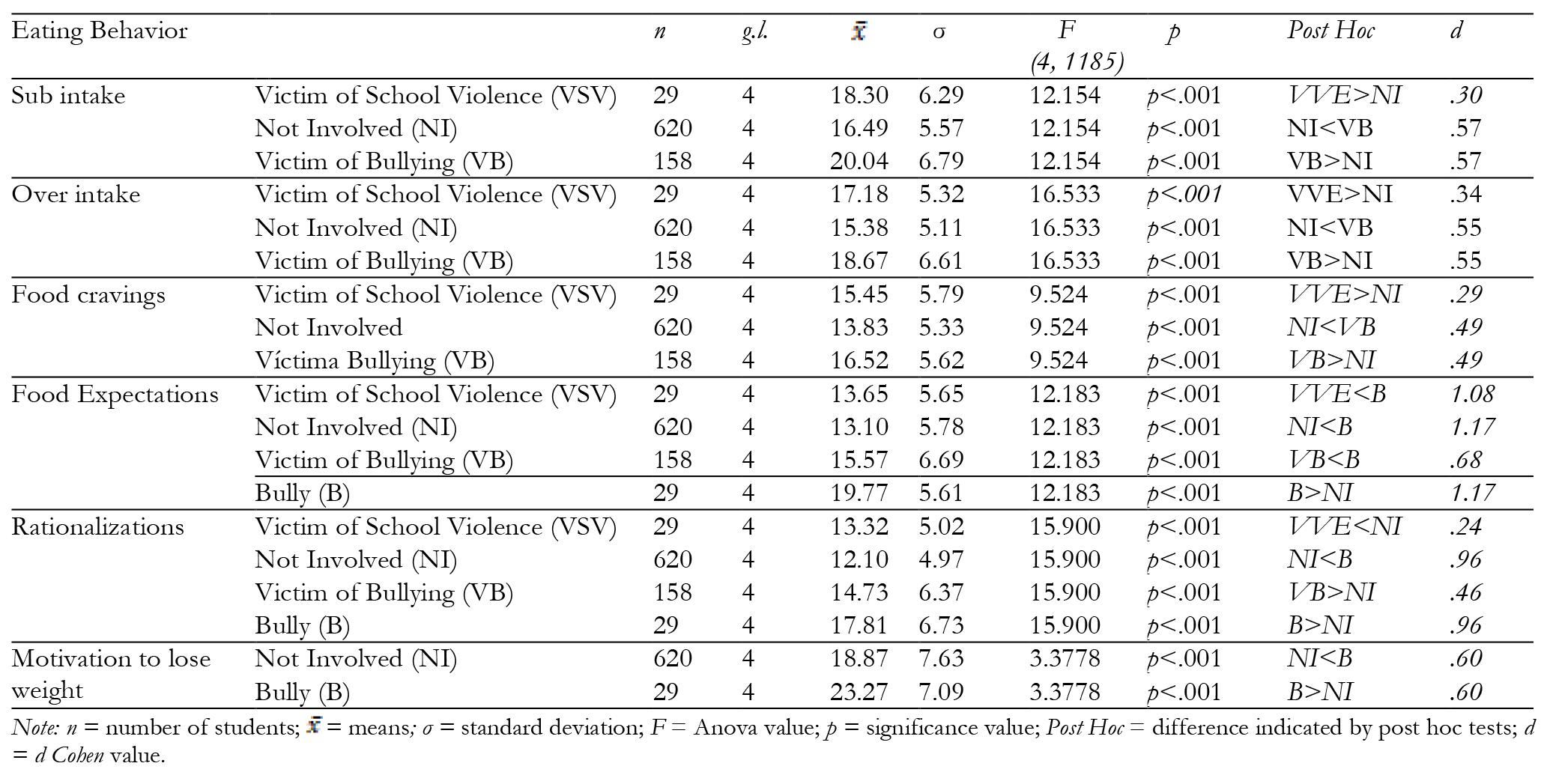

Habits and Attitudes related to eating Behavior.

Table 6 shows the means contrasts of the Habits and Attitudes related to eating behavior.

Table 6. Differences in participation in bullying episodes based on habits and attitudes related to eating behavior.

The ANOVA analysis indicates significant differences between student groups. Post Hoc contrasts indicate that students not involved, have a lower mean than the group of students who are victims in food sub-intake; Food over-intake; Food cravings; Rationalizations and it has a significantly lower mean than the bully group in in the following sub-scales: Expectations related to eating; Motivations to lose weight (see table 6).

Table 7 shows the contrast of means in the general health habits and psychosocial functioning scale, depending on student participation roles.

Table 7. Differences in participation in episodes of bullying according to general health habits and psychosocial functioning.

With regard to general health and psychosocial functioning habits (see Table 7), it was identified that the group of students, who do not get involved, also have significantly less mean than victims of bullying, victims of school violence and bully in the sub-scale: Social Isolation and Affective alteration. Students who do not get involved in bullying, have a higher mean in the Body image sub-scale, than victims of bullying and victims of school violence.

Discussion and Conclusions

The study provides novel information regarding the description of the characteristics of students who don not get involved in bullying episodes, information that will undoubtedly help the development of public policies that allow to disseminate in the population, (specially in developing countries) information to specialists, parents and teachers who help reduce the risk of engaging in aggressive episodes in the school context.

The results describe that students who do not participate in bullying, do not identify with any of the traditional stereotypes, in particular, with the called traditional male or traditional female stereotype, rather this type of student integrates into their repertoire, both the feminine and the masculine (androgynous), so they are able to take care of others, be friendly, helpful but also act under pressure, compete and make decisions, the above, will allow specialists in the area, to have more information so that they can provide an accurate guide in the development of public policies, as well as, transmit to families information regarding the education that is provided in the family, mainly, to remove the misconception that is transmitted from generation to generation, by believing that women are weak, that women are less than men, or that they can work in areas designed to care for others, which has certainly been proven to be associated with discrimination, exclusion and gender-based violence (Castillo & Montes, 2014).

The study's findings indicate that efforts should be directed to ensure that schools and families, the main micro systems of society, are those that transmit an education to children and young people, including behaviours and attitudes, both feminine and masculine (androgynous), both without a doubt, will help to respond comprehensively to the demands of today's society.

The results of the study complement what is identified in other research that highlights the association between being a victim and identification with the traditional female profile (Navarro, et al., 2016; Peña, Arias, & Sáez, 2017), and the association between violence and “machismo” (Morales et al., 2016; Navarro, et al., 2016; Peña, et al., 2017).

With regard to parenting practices, the results allow to describe the parenting practices used by parents of students who do not engage in bullying episodes, identifying that their parents do not direct physical, emotional or verbal abuse to educate them , do not over-protect them and do not exercise excessive control with them, in fact their parents are characterized by having leadership and educating them through effective parenting practices, such as so-called positive parenting, which is explained by empirical evidence which indicates that when parents value, support and communicate assertively with their children they favor the development of empathy, encouraging them to seek help when facing a problematic situation (Samper, Mestre, Malonda & Mesurado, 2015).

These results provide evidence that strengthens public policies aimed at establishing effective or positive parenting programs, through different institutions responsible for guiding families to reduce the risk of children involve risky behaviors.

The results also strengthen respect for children's rights, as parenting practices, without the use of: emotional and physical aggression, overprotection, or neglect, strengthen respect for children's rights, and contribute to the development healthier societies, without less violence, avoiding the development of victim profiles (Mendoza, 2017a; Samper et al., 2015) and aggressors (Cook, et al., 2010),in fact, it has been explicitly requested by Human Rights Commissions, that the schools be the ones that integrate families to be trained in parenting styles, thus avoiding the use of aggressions or physical punishments as educational strategies in order to reduce bullying in the school context (Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos, 2017).

With respect to the social skills of students called "non-involved" students, it is concluded that they are students who accept social norms, are empathetic, are not afraid to express themselves, communicate assertively and defend their rights without aggression, this evidence, which describes the students not involved, allows to know the skills that socially need to be strengthened in childhood and in young people, identifying that they are behaviors associated with prosocial behavior (Cuenca & Mendoza, 2017) and that they should be encouraged to be practice in the classroom during the school day. These results also strengthen research focused on reducing bullying behavior, through the strengthening of social skills (Silva da, et al., 2018; Yüksel-Sahin, 2015).

It is also concluded that students not involved, characterized by participating and collaborating in the common goals of team work, help to build solutions, have pro-social leadership through which they take the initiative to guide their peers to achieve group objectives, the latter adds more information to research in which it has been identified that the victim and bully students, are less effective in their social relations, that is, they have difficulty relating to peers, to start games, academic engagements or tasks, having less interactions with classmates (Santoyo & Mendoza, 2018).

According to the results of the study, students not involved are described, as students who accept social norms and customs, have the ability to reflect on their difficulties in establishing social relationships, are flexible and creative (in the problem-solving search), with the capacity to generate solution alternatives, identifying the consequences of their behavior, which allows them to choose the most appropriate one, which provides information to strengthen intervention programs, especially those aimed at controlling anger in children and adolescents, as the decrease in impulsivity is associated with the decrease in cognitive distortions that magnify situations, or limit students to perceiving only a duality (white or black) in problematic situations which prevents them from having alternatives to solution without aggression (Mendoza, 2017b; Mendoza & Maldonado, 2017).

The results of the study, complementing others in which it is indicated that the deficit in the establishment of social networks, is a predictor to play the role of victim or the role of bully in bullying (Kljakovic & Hunt, 2016), and has difficulty seek solutions to social relationship problems (Cook, et al., 2010).

With regard to habits and attitudes related to eating behavior, this study is one of the few who provide information with this variable regarding bullying behavior, noting that students called "not involved" are characterized by not having difficulties with over-intake and sub-intake, results that undoubtedly provide valuable information for the development of primary prevention programs, aimed at the development of health habits in children, which should undoubtedly be established and supervised by the main agent of change in the lives of children, parents.

These results are consistent with studies that have shown that children who are at the lowest risk of bullying are what are not overweight or obese (Bacchini, et al., 2015) and the students most at risk of being victims are those who are overweight and obese (Reulbach, et al., 2013; Waasdorp, Mehari, & Bradshaw, 2018).

Finally, it is also concluded that, students called "not involved" in episodes of bullying, have positive body image, have social resources that allow them to have social networks in school, and are the ones that exhibit the least affective alterations (stress, depression and anxiety), results that add more information to the association already identified among the body image deficits of bully and victims of bullying (Waasdorp, et al., 2018).

Limitations

Although eleven schools participated, one of the main limitations of the study is that there was no representative sample in the State in which the research was conducted, making it impossible to generalize the results, so for future research it is suggested to expand the number of participants further by opting for random type sampling.

It is proposed that for other studies the study variables be extended, especially those that belong to the social context of the students, such as the rate of violence of the colony in which they live, as well as the rates of violent acts that characterize the community in which they inhabit, providing information on the relationship of violence in its context and violence in its classroom.

texto en

texto en