Introduction

Trauma is used for all kinds of situations that shake, hurt and injure the mental and physical existence of the individual in many different ways. How and to what extent the traumatized person will be affected may vary depending on the type, frequency and severity of the event, and the characteristics of the person (Kalı Soyer et al., 2021). While post-traumatic stress often occurs after a single trauma, complex post-traumatic stress is a condition that can be seen in children and adults who experience trauma in the early period and for a long time. (Karadağ, 2022). Complex trauma tends to include at least one interpersonal trauma, defined as those that are intentionally perpetrated by another person (e.g., physical or sexual abuse), whereas non-interpersonal traumas may include experiences like exposure to natural disasters or serious accidents (Wamser-Nanney & Vandenberg, 2013, Ross et al., 2021).

Childhood traumatic experiences are, by their nature, experiences that negatively affect an individual's self-view, self-esteem, and perception of other people and life (Widom et al., 2018). According to the World Health Organization, traumatic experiences are defined as behaviours that include physical and emotional abuse, sexual harassment, neglect and exploitation, causing actual or potential harm to the child's health and development. When such experiences occur outside the family, strong family support and parental assistance can alleviate the development of post-traumatic pathology. On the other hand, especially the negative experiences with the family members who are the primary caregivers of the child and who are the object of attachment, further increase the psychological destruction of the child and severely impair many critical developmental competencies and mental health of the child (Gencer et al., 2016; Yektaş et al., 2018; Bulut, 2016). The effects of childhood traumatic experiences are certainly present in adulthood in varying extents (Bostancı et al., 2006; Özen et al., 2007; Yıldız, 2007; Şenkal & Işıklı, 2015; Kinniburgh et al., 2017; Yılmaz et al., 2003).

Child abuse and neglect continues to exist as an important problem in Turkey as well as all over the world. While emotional abuse is 36%, physical abuse 23%, sexual abuse 8-18% and neglect 16% worldwide (WHO, 2017), 78 out of 100 children in Turkey are subjected to emotional abuse and neglect (Turhan et al., 2006). Pelendecioğlu & Bulut (2009) reported that 5 of 10 families see child beating as a normal discipline tool. It is estimated that the rate of sexual abuse submitted to the court is 3% while the rate of unregistered abuse is estimated to be between 10-20% (UNICEF, 2010). According to the data of the Turkish Statistical Institute (TUIK), 150 thousand 615 children who came or were brought to the security units in 2020, mostly injuring (55.3%) crimes against family order (14.5%), sexual crimes (12.2%). have been victims of threats (4.5%) and deprivation of liberty (3%) (TUIK, 2021).

From the moment the child is born, the basis of his or her personality and psychological structure are shaped by the conclusions he or she draws from the interaction with the caregivers (Bowlby, 1969). Caregiving is not only about feeding but also about care, love and acceptance. The child regulates his or her behaviour, social relationships and adaptation to his or her adulthood with the foundations he or she establishes with a safe family environment where he or she feels loved (Bowlby, 1973; Arslan et al., 2011; Durmusoglu Saltalı & Arslan, 2011; Arslan, 2021). Ainsworth (1989) indicates that the attachment styles formed in childhood also affect the relationships in adulthood.

Unlike adults, children do not have the option to complain, leave or protect themselves in a different way. It is an innate tendency to trust their caregivers in order to survive. While neglect and abuse in the family cause attachment crisis in children (Bernet & Stein 1999, Mikulincer & Shaver 2007, Kinniburgh et al., 2017), the child tries to regulate his or her behaviors and emotions in order to protect his or her presence in the family. The source of the negative cognitive schemes observed in adulthood is also based on these negative experiences (Şenkal & Işıklı, 2015; Lök et al., 2016).

The sense of attachment, which is the survival instinct of children, is mainly shaped by the behaviour of their parents. It is known that even babies in the womb are affected by the psychological state of the mother, speech, and contact with the belly and give appropriate reactions (Dobson, 2017). With this characteristic, attachment to and integration with the mother or the primary caregiver of the child forms the basis of the psychological patterns Bowlby (1969, 1973).

According to Bowlby (1969, 1973, 1979, 1980), having a sensitive and always accessible caregiver that responds consistently to the needs of the child leads to the development of secure attachment. As a result, one perceives himself or herself as worthy of love and develops a positive self-model. This leads to the perception of others as reliable, accessible, consistent and supportive, and leads to the development of a positive model of others. In contrast, the caregiver's insensitive, over-intrusive, unpredictable and inconsistent reactions lead to the development of anxious attachment behaviours in the child. If the caregiver acts in a rejectionist or over-negligent way in care, the child may prematurely want to be independent or tend to break away from the attachment object. Frequent repetition of such behaviours may lead to the development of negative self-model defined by feelings of worthlessness and of negative model of others in which others are perceived as unreliable, inconsistent and cold (Main, 1990; Rothbard & Shaver, 1994). As a result, attachment affects individuals for a lifetime and mental models developed in early ages continue to function similarly in adulthood without much change (Bowlby, 1973, 1979).

This study was based on Bartholomew's Four Factor Attachment Model (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991) reorganized on the basis of Bowlby's theory of mental models. According to the model, two types of self-model were crossed with the model of others and four types of adult attachment styles were defined. In secure attachment style, one considers him or herself worthy and thinks that others are accepting and supportive. They are safe and comfortable in their relationship. Preoccupied style reflects feelings of worthlessness or not worthy of being loved and positive evaluations of others. Preoccupied attachment therefore tends to validate or prove themselves in close relationships. They are constantly obsessed with their relationship and have relatively unrealistic expectations of their relationship. In dismissing attachment style, self-worth (high self-esteem) and negative attitude towards others are present. Individuals with dismissing style give extreme importance to autonomy and defensively reject the need for others and the need for close relationships (Bartholomew, 1990). Dismissing individuals have a sense of autonomy and high self-esteem at the expense of a lack of intimacy. Eventually fearful style is the exact opposite of secure attachment style and reflects individual feelings of worthlessness and expectations that others are unreliable and rejecting (Bartholomew, 1990). While one does not consider himself or herself worthy of being loved, he or she also believes that others are bad and unreliable. In the model, preoccupied, dismissing and fearful attachment styles are evaluated in the insecure attachment group.

Secure Attachment associated with negative psychological health later in life secure attachment is more associated with positive psychological states (Sitko et al. 2014). Studies show that insecure attachment style is related to childhood trauma (Erozkan, 2016), trait anxiety, and external locus of control (Dilmaç et al., 2009), approaching problems in a negative way, lack of self-confidence (Arslan et al., 2012), interpersonal traumatic events. (Morina et. al, 2016), psychiatric disorders (Ozcan et.al, 2016). Also childhood trauma and traumatic experiences can have various negative effects on physical and mental health in adulthood (Crittenden & Landini, 2011; Kisiel et al., 2014; Read et al., 2014).

The study is aimed at revealing the effects of both traumatic experiences and physical, emotional and sexual dimensions of traumatic experiences on attachment styles. As can be seen from the explanations above; childhood attachment is associated with many positive and negative traits. In addition to this situation, studies show that traumatic experiences are among the most important problems of human life. It is thought that this research will provide a better understanding of the relationship between traumatic experiences and attachment styles. We hope that the findings will contribute to preventive, rehabilitative and developmental psychological support activities and will lead to new research.

Method

Correlational research design was used in the research. Correlational research designs measure the statistical relationship between two variables or more variables (Karasar, 2008). Emotional neglect/abuse, physical neglect/abuse and sexual abuse are independent variables of the study, constituting the sub-dimensions of general childhood traumatic experiences and childhood traumatic experiences. The dependent variables of the research are secure, preoccupied, fearful and dismissing attachment styles within the framework of the four factor attachment model and insecure attachment style obtained by grouping three types of attachment styles apart from the secure attachment style.

Study Group

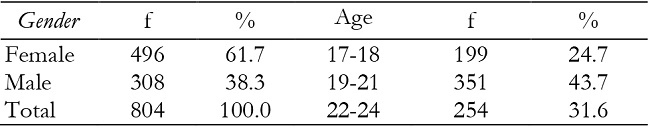

The study was conducted on 804 participants aged between 17 and 24. Data collection tools were applied to all students who were willing to participate in the study in accordance with the principle of volunteering and 31 of the 835 participants were excluded from the assessment due to their lack of scales. Demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

As seen in Table 1, 61.7% of the participants are female and 38.3% are male. The rate of participants in the 17-18 age groups is 24.7%, 43.7% in the 19-21 age group, and 31.6% in the 22-24 age group.

Data Collection Tools

The first data collection tool used in the study is Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ). It was developed by Bernstein et al. (1997) in order to measure the traumatic experiences experienced before the age of 8. High scores on a 5-point Likert-type scale consisting of 40 items indicate that neglect and abuse are more common in childhood and adolescence. The scale can be evaluated as total score and can be scored according to three sub-dimensions: physical neglect and abuse, emotional neglect and abuse, and sexual abuse. Bernstein et al. (1994) reported that the scale's Cronbach's alpha coefficient ranged from 0.79 to 0.94. The Turkish adaptation of the scale was conducted by Aslan and Alparslan (1999) and Cronbach's alpha coefficient was determined as follows: .94 for physical neglect and abuse,.95 for emotional neglect and abuse,.94 for sexual abuse, and .94 for the overall of the scale (Aslan & Alparslan, 1999). In the study, 19th and 37th items in the dimension of emotional neglect and abuse were excluded from the analysis as factor loads were found to be insufficient.

The Relationship Styles Questionnaire used in the study was developed by Griffin and Bartholomew (1994) to measure four adult attachment styles: insecure, dismissing, fearful and preoccupied. The scale adapted to Turkish culture by Sümer and Güngör (1999) consists of 17 items. The scale has the following attachment dimensions: secure, fearful, preoccupied and dismissing. However, it can be evaluated in two dimensions as secure attachment and insecure attachment. The internal consistency coefficient of the scale was reported as .67. The increase in scores in each dimension indicates the dominance of the attachment style that is named after that dimension.

Procedure and Data Analysis

Google Formswas used to collect online survey data. All procedures in the current study were suitable with the ethics committee and with the Belmont Report-1979. In the analysing process, first, the data were screened for incorrect or incomplete coding. Multivariate outliers and normality of variances were tested before the analysis.

The data obtained from the study were analysed by using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) for Windows 22.0 and Amos 22.0 program. Descriptive statistical values, skewness and kurtosis values were used to test the suitability of the data for normal distribution and internal consistency coefficients were calculated to test the reliability of the scales. In order to determine the effect of traumatic experiences on adult attachment styles, three models were created and theoretical models were tested using structural equation modelling. RMSEA, CFI, IFI, GFI, AGFI and CMIN/DF scores were calculated to determine the goodness of fit of the models established in this respect and then the results were interpreted through the Standardized β, standard error and R2 values.

Results

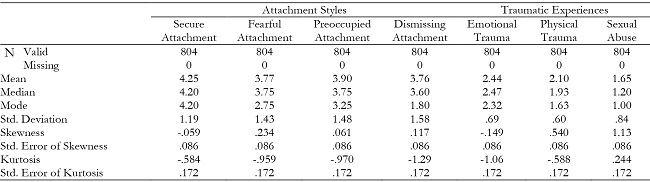

Prior to testing the models established in the research, first level confirmatory factor analysis of two data collection instruments was performed and internal consistency coefficients were calculated. The results of the analyses performed to this end are shown in Table 2.

The structures were validated after being tested in accordance with the first level confirmatory factor analysis and internal consistency findings conducted to test the validity of the scales used in the study. In addition to these analyses, descriptive statistical values were calculated to control the distribution of the collected data.

As shown in Table 3, the data collected with the three measuring tools show normal distribution.

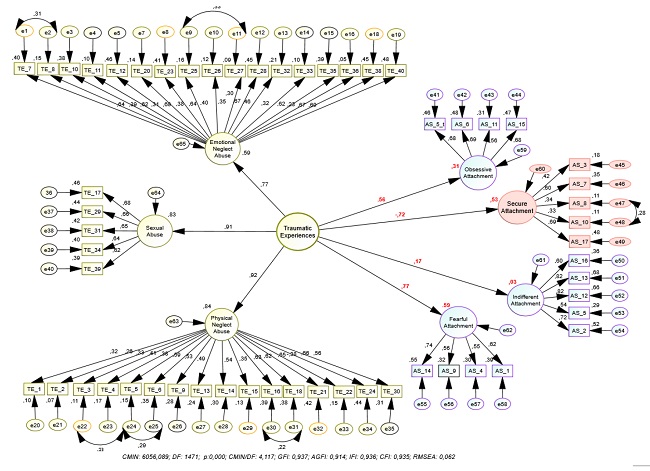

In the study, the model created between 4 sub-dimensions of attachment styles and overall traumatic experiences was tested first. The calculated values of the model are shown in Figure 1.

By determining the variables that reduce concordance of the model and creating new covariance for the residuals with high covariance values, (e2-e2; e9-e11; e22-e24; e24-e25; e30-e31; e47-e48), the following calculation was made: X2/Df = 4.117, GFI= .937, AGFI= .914, IFI= .936, CFI= .935 and RMSEA= .062. These values indicate that the data conforms to the model. The standardized beta, standard error and significance values of the pathways extending from traumatic experiences to attachment styles are shown in Table 4.

Table 4: The Results of the Analysis of Traumatic Experiences (General) and Attachment Styles Model.

According to these findings; traumatic experiences had a negative and significant effect on secure attachment (β = -.724; p < .05). This shows that as the traumatic experiences decrease, the secure attachment increases. That is, as the traumatic experiences increase, the secure attachment decreases. According to the findings, traumatic experiences had a positive significant effect on fearful (β = .773; p < .05) and preoccupied attachment (β= .563; p < .05). This shows that traumatic experience scores increase or decrease with fearful and preoccupied attachment scores. However, it is seen that traumatic experiences are not a significant predictor of dismissing attachment (β = .171; p > .05). Trauma experiences account for 53% of secure attachment (R2 = .525), 59% of fearful attachment (R2 = .594) and 31% reoccupied attachment (R2 = .313).

Figure 1. Impact of Traumatic Experiences on Secure, Fearful, Preoccupied and Dismissing Attachment.

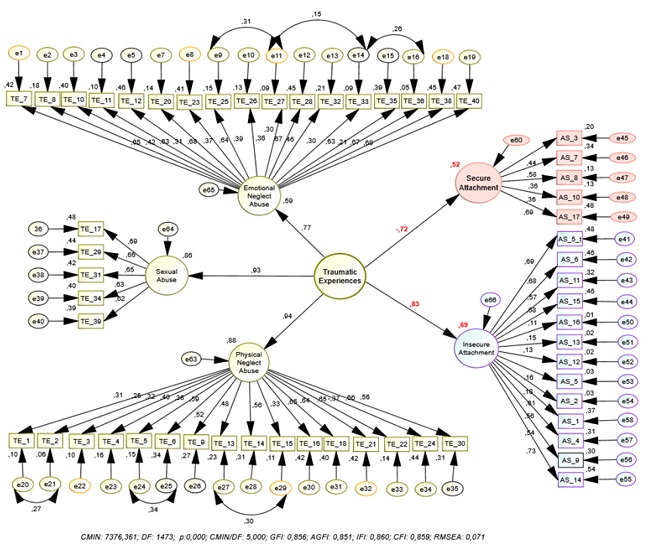

In accordance with the instructions for the relationship styles scale used in the research, fearful, preoccupied and dismissing attachment were combined under the title of insecure attachment and a separate model was established and tested. The results obtained from this model of the relationship between traumatic experiences and secure and insecure attachment dimensions are shown in Figure 2.

By determining the variables that reduce concordance of the model and creating new covariance for the residuals with high covariance values, (e9-e11; e11-e14; e14-e16; e27-e29; e20-e21; e24-e25), the following calculation was made: X2/Df = 4.498, GFI= .856, AGFI= .851, IFI= .860, CFI= .859 and RMSEA= .071. These values indicate that the data conforms to the model. The standardized beta, standard error and significance values of the pathways extending from traumatic experiences to secure and insecure attachment styles are shown in Table 5.

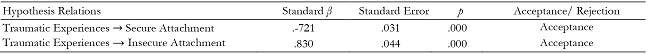

Table 5: The Results of the Analysis of Traumatic Experiences (General) and Secure and Insecure Attachment Styles Model.

According to these findings; traumatic experiences had a negative significant effect on secure attachment (β = -.721; p < .05); and a positive significant effect on insecure attachment (β = .830; p < .05). The traumatic experiences accounted for 52% of the change in secure attachment scores (R2 = .518) and 69% of the change in insecure attachment scores (R2 = .689).

The scale of traumatic experiences used in the research has three sub-dimensions: physical neglect and abuse, emotional neglect and abuse, and sexual abuse. A third model was created and analysed in order to find out which kind of traumatic experience explains the attachment styles to what extent. The findings obtained from the model of the relationship between sub-dimensions of traumatic experiences and secure and insecure attachments are shown in Figure 3.

By determining the variables that reduce concordance of the model and creating new covariance for the residuals with high covariance values, (e9-e11; e11-e14; e14-e16; e27-e29; e20-e21; e24-e25), the following calculation was made: X2/Df = 4.949, GFI = .871, AGFI = .867, IFI = .866, CFI = .865 and RMSEA = .070. These values indicate that the data conforms to the model. Standardized beta, standard error and significance values for the pathways extending from physical neglect-abuse, emotional neglect-abuse and sexual abuse to secure and insecure attachment styles are shown in Table 6.

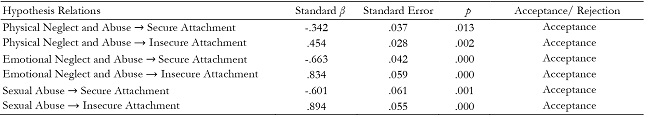

Table 6: The Results of the Analysis of Sub-dimensions of Traumatic Experiences and Secure and Insecure Attachment Styles Model.

According to these findings, there is a negative significant relationship between sexual, emotional, and physical trauma and secure attachment; and a positive significant relationship between insecure attachments. However, the traumatic experiences with the strongest impact on insecure attachment were sexual abuse (β = .894; p < .05) and emotional neglect and abuse (β = .834; p < .05). Whereas the experience with the least impact was physical neglect and abuse (β = .454; p < .05). Secure attachment was mostly affected by emotional neglect and abuse (β = -.663; p < .05). In terms of the impact on secure attachment, the second strongest was sexual abuse (β = -.601; p < .05), the third was physical neglect and abuse (β = -.342; p < .05).

Discussion

The study examined the effects of childhood traumatic experiences on adult attachment styles. It was concluded that traumatic experiences have a positive significant effect on fearful and preoccupied attachment; and a negative significant effect on secure attachment. On the other hand, traumatic experiences did not satisfyingly explain the dismissing attachment style. Mental models that form based on the attachment experiences at early ages affect the self-esteem, self-expectations, beliefs and emotions of the individual, and the level of trust in others and the comfort levels felt in social relationships. (Cassidy, 1988; Hazan & Shaver, 1994; Kinniburgh et al., 2017).

Numerous research findings suggest that childhood experiences are a significant predictor of secure and insecure attachment. (Zerenoğlu, 2011; Bozdemir & Gündüz, 2016; Erozkan, 2016; Raby et al., 2017; Kinniburgh et al., 2017; Yoder et al., 2019). The common result of these research findings is that attachment styles develop based on childhood experiences. In addition many studies examined within the scope of the subject suggest that having a secure attachment style is positively correlated with positive psychological concepts such as optimism, self-efficacy, self-confidence, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction while insecure attachment is negatively correlated with them (Savcı & Aysan, 2016; Kinniburgh et al., 2017; Şenkal & Işıklı, 2017; Yektaş et al., 2018). This is an indication that the child's secure bond with primary caregivers forms the basis of mental health.

When the results of the research are generally evaluated, a negative significant relationship between traumatic experiences as a whole and secure attachment and a positive significant relationship between these experiences and fearful and preoccupied attachment have been found. These findings are consistent with the research results of Zerenoğlu (2011). This study examined the relationship between traumatic experiences and attachment styles of university students, and reported a positive significant relationship particularly between fearful attachment style and traumatic experiences. In this study, no significant relationship was observed between traumatic experiences and dismissing attachment. In other words, while traumatic experiences significantly predict secure, preoccupied and fearful attachment styles, they do not explain dismissing attachment styles satisfyingly. Ainsworth et al. (1978) emphasize that the dismissing attachment style stems from the fact that the primary caregivers of the child are cold, distant and avoiding contact. If the caregiver acts in a rejectionist or over-negligent way in care, the child may prematurely want to be independent or tend to break away from the attachment object (Sümer & Güngör, 1999). These findings in the literature explain why this study did not find any significant relationship between traumatic experiences and dismissing attachment. In summary, experiences that lead to dismissing attachment may not be traumatic experiences. On the other hand, childhood experiences leading to fearful and preoccupied attachment were direct traumatic experiences. Cloitre, et al. (2008) reported that adults with low childhood traumas are more likely to adopt secure and dismissing attachment styles; however, adults with high traumatic experiences have more preoccupied and fearful attachment styles. The research conducted by Dülger (2019) concluded that the anxiety level of adults with traumatic experiences is much higher than avoidance behaviour. The summarized findings of these studies are consistent with the results of the research.

The present study formed a distinct model by gathering fearful, preoccupied and dismissing attachment dimensions under the roof of insecure attachment. As a result of the established model, traumatic experiences had a negative significant effect on secure attachment and a positive significant effect on insecure attachment. This result supports the first model findings tested. However, traumatic experiences were predictive of insecure attachment to a greater extent. While traumatic experiences explain secure attachment by 52%, the rate of explaining insecure attachment is 69%. This supports the view that traumatic experiences have more effect on insecure attachment. Kinniburgh et al., (2017) found that maltreatment in childhood explains 90% of insecure attachment patterns.

An important distinction of the study is that it also tests the relationship between physical, emotional, and sexual dimensions of traumatic experiences and attachment styles. According to the results obtained from the third model of the study, the strongest relationship was observed between sexual abuse and insecure attachment. This was followed by insecure attachment and emotional neglect and abuse. These findings show that sexual and emotional trauma was significantly more effective on insecure attachment than physical neglect and abuse. The findings of this model also imply that emotional neglect and abuse are the most damaging experiences for secure attachment. Another important finding of the third model is that physical trauma is relatively less effective on attachment styles than relative sexual and emotional trauma. This may imply that physical neglect and abuse is a more tolerable type of trauma by children than sexual and emotional abuse. There are studies supporting this finding and interpretation based on this research. Turhan et al. (2006) reported that emotional abuse is particularly effective on psychological functioning in adulthood. The same study emphasized that emotional abuse in Turkey is in the first place among other forms of abuse, with a rate higher than 78%. Örsel et al. (2011) found out emotional abuse in 82% of 183 patients with at least one psychiatric diagnosis. There are also studies pointing out that emotional abuse is a significant predictor of such problems as depression, aggression, social deterioration, and low self-perception (O'Hagan, 1995; Arman, 2007). Although the effects of physical and sexual abuse disappear with time through appropriate and timely interventions, the effects of emotional neglect and abuse can be permanent (Topbaş, 2004).

The study determined that sexual abuse is the most effective trauma on attachment styles. Küçük (2016) states that a child who is exposed to sexual abuse is mostly exposed to physical and emotional abuse as well. This situation explains the findings. Experiences of sexual abuse within the family may damage the child's sense of self-confidence and may lead to the development of feelings of guilt (Bilginer et al., 2013).

Limitations and Recommendations

The study was limited to a sample of 18-24 age groups. Conducting studies on young adulthood and adulthood will provide a better understanding of the long-term effects of traumatic experiences on attachment styles.

Descriptive survey method was administered in the study. The research that will be conducted in the experimental and quasi-experimental design with individuals with childhood traumatic experiences will provide findings of high internal consistency.

The study revealed the effect of childhood traumatic experiences on attachment styles consistent with the literature. We hope that the results of present and similar studies will be utilized in both preventive and curative psychological support and relief studies. The study is aimed at due diligence. There is a need for research that will contribute to the development of group therapies and psycho-educational programs for individuals with traumatic experiences.