Introduction

Gender differences are undoubtedly important in political and economic domains, and generally in the dynamics of social interactions. Inequality indices between men and women are a demographic reality that asymmetrically structures our societies (Lorente et al., 2020). Gender research faces the challenge of demonstrating if the binary vision of sex, gender and sexuality must be replaced with another non binary and fluent vision (Morgenroth & Ryan, 2020), and if differences in sexual conducts must be dealt with from either an evolutionary perspective (Buss, 2006; Sevi et al., 2018) or another based on differential and binary socialization in gender roles (Eagly & Wood, 2012). Collectively, these issues consider the need to discover and explain both the individual and collective changes that categorizing society according to gender implies.

Gender differences

Studying gender differences was initially performed from the biological conception, which stressed sexual dimorphism (Fernández, 2011). What is masculine and what is feminine were identified with each main sexual category, in which humans (i.e., man and woman), and many other living beings, were divided according based on reproduction functions (Wood & Eagly, 2015). From the 1970s, it was assumed that the social roles assigned to men and women were the basis to characterize masculinity and feminity (Eagly & Wood, 1999, 2012). According to this assumption, the division was work based on gender favoured stereotyped conceptions, which assign different roles to women (e.g., housework and the role of people carers) and to men (e.g., occupations in the public domain and a competitive role toward accomplishments) (Hentschel et al., 2019). Traditionally, what was expressive or communal was named the feminity (F) dimension, which included typical women’s traits, while what was instrumental or agentic was named the masculinity (M) dimension (Bakan, 1966; Parsons & Bales, 1955). Gender stereotypes served for characterizing others in M and F terms, but also for someone to characterize his/herself (Koenig & Eagly, 2014). Most people tend to self-attribute the typical characteristics of their sex’s gender stereotype (i.e., personas sex-typed) and exclude those that are culturally considered typical of the other sex (Bem, 1974; Spence & Buckner, 2000). Nonetheless, four gender identity types can prevail (i.e., masculine, feminine, androgynous, undifferentiated) depending on how people identify themselves, to a greater or lesser extent, with the traits of both the M and F dimensions (Bem, 1974, 1981; Colley et al., 2009).

Measuring gender role

The Bem Sex-Role Inventory (BSRI; Bem, 1974) is one of the most widely used scales to measure gender identity as a self-description in compliance with a series of personality traits. The original BSRI version (Bem, 1974) included 60 items that referred to physcological traits or characteristics that were distributed into three subscales: Masculinity (M), Femininity (F) and Social desirability. Later Bem (1979) developed a short version that halved the original number of items of each scale. The reliability of the original scale’s internal consistence gave a Cronbach’s alpha of .86 for M and one of .82 for F. Ever since it was published, this scale has led to considerable methodological and theoretical debate.

Much of the methodological debate has been about the scale’s structure. Its results, obtained with samples mainly made up of university students and from different countries, support the BSRI’s multidimensionality (Choi & Fuqua, 2003; Choi et al., 2007, 2009; Fernández & Coello, 2010; Fernández et al., 2007). Nevertheless, the BSRI structure changes according to the ethnic group the sample belongs to (Lee & Kashubeck-West, 2015). Confirmatory factor analyses carried out in older adult samples support a 2-factor model (Ahmed et al., 2016).

Masculinity and femininity constructs

From a theoretical point of view, as the BSRI is made up of items that refer to instrumentality and expressiveness, it does not allow the M (agency) and F (communality) constructs to be measured on the whole (Choi & Fuqua, 2003; Hoffman & Borders, 2001). Recent results back this limitation of the BSRI by showing that both agency and communality are multidimensional ―i.e., agency dimensions: instrumental competence, leadership competence, assertiveness and independence; communality dimensions: concern for others, sociability and emotional sensitivity (Hentschel et al., 2019)―. The results obtained with Spanish participants demonstrate that only a few BSRI items are considered to be characteristically masculine or feminine traits (Ferrer-Pérez & Bosch-Fiol, 2014).

Variations in masculinity and femininity scores: Do they indicate collective or individual changes?

The changes noted in BSRI scores for different age groups have been shown as a threat for construct validity. For example between 1974 and 2012 in samples from the USA, the tendency for men to obtain higher scores in M than women dropped, while women’s scores lowered in F and rose in M (Donnnelly & Twenge, 2017; Twenge, 1997). If gender identity constitutes the interiorization of the cultural meanings assigned to gender roles (Wood & Eagly, 2015), then these changes in the M and F scores reported by men and women might result from the interaction between historic events and someone’s gender evolutionary development. On the one hand, the gender construct acts as a basis to define the Self in collective identity terms; that is, as a member of one gender group (e.g., masculine) or the other (e.g., feminine) (Tajfel, 1981). Therefore, transgenerational changes in men and women’s M and F scores might reflect the cultural obsolescence of F and M in the BSRI. On the other hand, measuring gender identity can be understood as giving a self-description from a list of traits without having to induce gender categorization. As previously suggested, when people answer such measures, they might not consider that traits have a masculine or feminine meaning, or they may indicate something about them belonging to gender groups (Wood & Eagly, 2015). If this were indeed the case, the changes noted in M and F in the BSRI would help to understand of life-span gender development (Strough et al., 2007).

Research objectives

In light of all this, measuring gender with the BSRI contributes to increase knowledge about interindividual differences in the interiorization of traditional masculine and feminine gender roles. Having a short version in Spanish would allow interindividual differences in the traditional gender traits of a Spanish-speaking population to be evaluated, and the relation between masculine and femenine traits and other psychological and behavioral traits to be described.

The objective of this study was to propose a short Spanish version of the BSRI (Bem, 1974; Fernández et al., 2007). To this end, the factorial structure, the reliability of internal consistence and some pieces of evidence for its validity were examined based on the relation of its measures to other variables. As pointed out, we assumed that the validity of the proposed BSRI version would be limited by the nature of the specific subdimensions of agency (i.e., instrumentality) and communality (i.e., expressiveness) shaping the scale. Differences in M and F per sex and age group were analyzed, and differences in the M and F scores were expected according to both variables (Donnelly & Twenge, 2017).

According to other authors (Ajzen, 2020; Eagly & Chaiken, 1993; Wood & Eagly, 2015), significant correlations can be expected between BSRI scores and other attitudes and behaviors that are culturally and unequally linked to men and women. Social definitions and expectations about masculinity and femininity, in addition to influencing early sexual activity (Gazendam et al., 2020), determine how someone is perceived when the sexual conducts are performed (Marks, 2008). Thus sexually active men are better evaluated than women (Muehlenhard & Quackenbush, 2011). With these findings, first the relation between self-description in masculine traits (M) or feminine traits (F) terms and two sexual variables (e.g., age of first sexual intercourse and number of sexual partners), which are differently manifested in men and women, was described (Arcos-Romero & Sierra, 2020; Ashenhurst et al., 2017; Stroope et al., 2015). Second, the relation between the M and F scores of the proposed BSRI version and competitive motivation was analyzed to maintain a hierarchy among existing groups in society (Asbrock et al., 2010; Caricati, 2007; Sidanius et al., 2004). The asymmetric social hierarchical structuring that exists according to gender affects all areas of social life. To measure favorable individual willingness to asymmetry among groups, the Social Dominance Orientation (SDO; Sidanius et al., 2004) construct was proposed, which includes two different dimensions (Pratto et al., 1994; Silván-Ferrero & Bustillos, 2007): (a) support for group-based dominance, which measures the psychological and individual tendency to accept and support the social domain based on one’s own group; (b) general opposition to equality, which measures the tendency to oppose social equality (Jost & Thompson, 2000). Evidences shows that men obtain higher SDO scores than women (Sidanius et al., 2000), and the different socialization processes that men and women follow might affect gender differences in SDO scores (Caricati, 2007; Schmitt et al., 2017).

Method

Participants

The sample comprised 2,672 Spanish participants of he-terosexual orientation (1,289 men, 1,383 women) recruited by non random sampling. Participants´ age range went from 18 to 87 years old (M = 40.27; SD = 15.04) distributed into these age groups: 18-25, 26-35, 36-55, and 56 years or more. The distribution of their level of education was as follows: 2.7% no studies; 11.9% Elementary School; 24.7% High School; 59.8% University. The mean of age their first sexual relation was 18.29 years old (SD = 3.5), and the mean of the number of sex partners was 5.23 (SD = 10.66).

Instruments

- Socio-demographic questionnaire. It includes information about sex, nationality, sexual orientation, age, level of education, age their first sexual relation, and number of sexual partners.

- The Spanish version of the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI; Bem, 1974; Fernández et al., 2007). It evaluates gender role or the presence of both male and female personality traits in the same person with 40 items answered on a 7-point Likert-type scale from 1 (never) to 7 (always). In the original version, items were distributed into two dimensions: M and F. The scale showed suitable internal consistence, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients .82 for M and .74 for F.

- The Spanish version of the Social Dominance Orientation Scale (SDOS; Pratto et al., 1994; Silván-Ferrero & Bustillos, 2007). It is made up of 16 items that are answered on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in the original scale was .91. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was .81.

Procedure

The participants were recruited from the general Spanish population by a non random sampling procedure. Instruments were handed out as printed documents at different universities, social centers and associations. A snowball procedure was also employed. The participants individually and privately provided answers. They handed in the completed survey in a sealed envelope when they finished. The subjects accepted informed consent, which indicated the study purpose, the charac teristics of the instruments, and that the ano-nymity and confidentiality of their answers would be guaranteed. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee in Human Research at the University of Granda (Spain).

Data analysis

For the evidence of validity based on the BSRI’s internal structure, the sample was randomly divided into two subsamples. Subsample 1 (n = 1,394) was used for the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and subsample 2 (n = 1,278) for the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). With subsample 1, the factorial structure of the original 40-item version was explored by 23 different methods to obtain an estimation of the number of factors. As the factorial structure was supported by a large number of methods, the EFA was performed using the Maximum Likelihood Estimation Method. With subsample 2, after taking into account the obtained EFA results, a CFA was carried out in the polychoric matrix using the Robust Estimation Method, which is particularly indicated for non parametric samples with ordinal data, and the Weighted Least Squares Means and Variance Adjusted (WLSMV; Beauducel & Herzberg, 2006; Carlier et al., 2019; Hirschfeld & von Brachel, 2014; Hu & Bentler, 2016). To consider the fit of an instrument to be good, the following criteria were contemplated: CFI and TLI > .90 and RMSEA < .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Manrique & Semenova, 2015). Then the ordinal alpha was calculated for the instrument’s reliability of internal consistence. For pieces of evidence for validity based on the relation to other variables, the BSRI scores between men and women, and among age groups (18-25; 26-35; 36-55, 56 years or more), were first compared. Second, correlations were observed with age of first sexual intercourse, number of sexual partners and SDO.

Results

Sources of validity evidence based on the internal structure

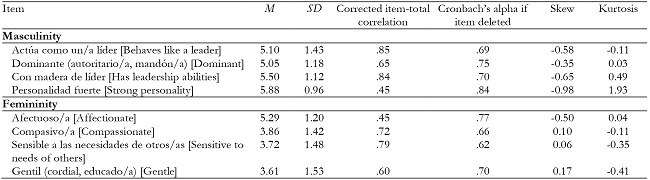

First of all, the factorial structure of the original 40-item BSRI version was examined using Subsample 1. More than 20% of the applied methods (t, p, acceleration factor, R2 and VSS complexity 1) supported a bifactorial structure, which was examined by an EFA. The distribution of items proposed for this preliminary analysis explained only 25% of variance. For this reason, and for the purpose of favoring the instrument’s psychometric guarantees, the items whose communality was higher than .30 were selected from both factors. Eight items met this criterion in the first proposed factor, but two were removed for having shared factorial loading. Four items were selected by following the same communality criterion in the second factor. The four items for each factor with the most communality were selected to equate the number of items in both factors. Next in the shorter 8-item version, the EFA supported the bifactorial structure with 40% of the methods (t, p, optimal coordinates, acceleration factor, parallel analysis, Kaiser criterion, SE Scree, VSS complexity 1, Velicer’s MAP) and accounted for 50% of explained variance (see Table 1).

Table 1: Factor loadings for the BSRI items obtained from EFA.

Note.The items maintain the numbering of the original 40-item version. Factor loadings below .30 were removed from the Table.

Then this 8-item bifactorial structure was tested by a CFA in Subsample 2. Its results showed a good fit for the bifactorial structure: RMSEA = .072; 90% CI RMSEA = .061-.082; CFI = .990; TLI = .987; χ2 (28) = 13766.172, p < .001. Figure 1 illustrates the flow chart of the two-dimensional model with standardized loadings for each factor.

Internal consistence

Internal consistence was analyzed by calculating the ordinal alpha for each factor. The results revealed an ordinal alpha of .84 for factor 1 M and one of .75 for factor 2 F. As Table 2 shows, the elimination of the item Affectionate in factor F slightly improved its reliability. However, a decision was made to maintain this item to have a similar number of items in both factors.

Sources of validity evidence based on associations with other variables

First the means of the scores for both factors between men and women were compared. For the factor M scores, significant differences were found (t = 2.82, p < .01, d = 0.12), and men scored higher (M = 16.76, SD = 4.55) than women (M = 16.21, SD = 4.92). Significant differences (t = -8.61, p < .001, d = -0.36) also appeared in factor F, but in this case men scored less (M = 21.11, SD = 3.44) than women (M = 22.31, SD = 3.30).

This was followed by examining the diferences in both the BSRI subscales among the various age groups. Significant differences were observed in factor M (F(3, 2347) = 9.66, p < .001). The 18-25 years age group (M = 17.14, SD = 5.75) showed higher scores than age groups 36-55 years (M = 16.30, SD = 4.79) and 56 years or more (M = 15.46, SD = 5.02). Age groups 26-35 years (M = 16.78, SD = 4.01) and 36-55 years obtained higher scores than the 56 years or more one. No significant differences among age groups were found in factor F.

Finally, the scores of the two BSRI factors correlated with the variables, but differently in men and women, and were related to sexuality and individual willingness toward asymmetry among social groups. A significant correlation was observed, and in the expected direction, between factor M and age of first sexual intercourse (r = -.135, p < .01), number of sexual partners (r = .120, p < .01) and the total SDO score (r = .059, p < .01). The correlation of factor F was only significant with the SDO score (r = -.264, p < .01).

Discussion

Studying gender differences involves having to face several challenges. On the one hand, explaining and describing macrosocial or collective changes (e.g., economic divide and power sharing) brought about by society’s asymmetric structuring from gender. On the other hand, identifying how men and women with traditional gender roles contribute to maintain social gender inequalities in force. In this sense, gender studies must advance in acquiring knowledge about interindividual differences in gender traits. Furthermore, gender differences need to be studied in diverse cultures; because, in this way, the factors determining these differences (e.g., cultural, socio-structural, individual) can be identified.

The BSRI constitutes a measure of self-description in terms of gender traits, which does not necessarily induce the social categorization of gender in the person (Wood & Eagly, 2015). Hence the BSRI’s merit is to inform the extent to which individuals identify themselves with traditionally masculine and feminine qualities. Very few studies have analyzed interindividual gender differences with Spanish-speaking samples and from various cultural origins.

The main objective of this study was to examine the factorial structure and reliability, and to provide evidence for validity based on the relation of its measures to other constructs, of the Spanish version of the BSRI (Bem, 1974; Fernández et al., 2007) in a mixed adult sample, in both sex and age terms, from the Spanish heterosexual population. The EFA evidenced a bifactorial structure. After a few modification, its fit in the CFA, which was carried out in a second independent sample, was good. The final proposal is a short bifactorial scale with 8 items taken from the original 40-item version. This version showed suitable construct validity, good internal consistency reliability coefficients and, due to their relationships with other variables, evidence of validity. Four M-related items were grouped in the first factor (“Actúa como líder” [Behaves like a leader], “Dominante (autoritario/a, mandón/a)” [Dominant], “Con madera de líder” [Has leadership abilities] and “Personalidad fuerte” [Strong personality]). Four other F-related ones were grouped in the second factor (“Afectuoso/a” [Affectionate], “Compasivo/a” [Compassionate], “Sensible a las necesidades de otros/as” [Sensitive to the needs of others] and “Gentil (cordial, educado/a)” [Gentle]). In line with Hentschel et al. (2019), factor M traits refer to the leadership competence and assertiveness dimensions, whereas factor F traits denote two dimensions: concern for others and sociability.

We believe that working with scores from diverse samples, both in sex and age, can be a method to ensure the measure’s discriminant validity. By comparing the M and F scores in the two samples made up of men and women, the obtained result backed the link between biological sex and self-definition according to the traits traditionally associated with gender (Bem, 1974; Spence et al., 1975). That is to say, men (vs. women) scored higher in M, and women’s scores (vs. men) were higher in F.

Diversifying the participants’ age allowed us to note some changes related to person’s evolutionary stages, even though each life stage entails gender norms and expectations, which have also changed throughout different historic eras. When comparing the M and F scores in the four samples formed by the age groups (18-25 years, 26-35 years, 36-55 years and 56 years or more), the general pattern of the results showed that the M scores were higher for the participants from the younger age groups than for the participants aged 56 years or more. No differences in the F scores were found among the sample’s age groups. Jointly these results not only evidenced the discriminant validity of the proposed scale’s version, but also backed the relation between cultural or social changes and developing self-definition in terms of traditional gender traits (Strough et al., 2007). Previous studies indicate that women’s F scores have lowered since the third wave of feminism at the start of the 1990s (Donnnelly & Twenge, 2017; Twenge, 1997). They also suggest that the lower F scores obtained in recent years might be due to prolonged adolescence and delayed motherhood, which is considered a fundamental life event for women to reinforce their feminine traits (Donnnelly & Twenge, 2017). In light of all this, the participants in this study with higher M scores, age groups 18-25 years and 26-35 years, would be more exposed to the influence of the third wave of feminism. On the BSRI’s construct validity, it has been suggested that if recent generations of men and women perceive BSRI items as gender traits, they might opt to not self-describe themselves with the scale’s traits; in this way the person is dissociated from the traditional conception of masculinity and feminity (Helgeson, 2015). More research is necessary to test this assumption. However, not finding any differences in the F scores according to the age groups could be indicating a tendency not to support the traditional conception of femininity when it is understood as concern for others and sociability.

Gender roles include lots of domains and dimensions, hence the usefulness of the BSRI to predict attitudes and conducts will be conditional on the nature of the dimensions measuring constructs M and F (Fernández, 2011; Spence & Buckner, 2000). Based on this assumption, we analyzed the relation of the scores in M and F with some sexual variables (age of first sexual intercourse and number of sexual partners) that have been differently associated with men and women in cultural terms. The results showed that the pattern of the relation between each gender dimension and sexual conducts was the opposite of, but consistent, with gender differences. The M dimension was related indirectly to age of first sexual intercourse, and directly to number of sexual partners (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2021; Arcos-Romero & Sierra, 2020; Calvillo et al., 2020; Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2019). The F dimension was related directly to age of first sexual intercourse, and indirectly to number of sexual partners (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2021; Arcos-Romero & Sierra, 2020; Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2019).

As further proof of the validity of the measures obtained with this brief version of the BSRI, we analyzed the relation between the scores in M and F and the scores in SDO. On the whole, the results indicated that the relation between the interiorization of traditional gender traits and SDO followed a similar pattern to the relation found between biological sex and SDO, according to which men score higher in SDO than women (Sidanius et al., 2000). In the present study, M and F was related directly and indirectly to SDO, respectively. These results seem to back the notion that the interiorization of traditional gender traits which men and women experience during different socialization processes are related to SDO scores (Caricati, 2007; Schmitt et al., 2017).

Limitations and Conclusions

First of all, it is necessary to highlight that the presented scale only measures one aspect of gender identity: self-definition in terms of gender roles, and that such self-definition refers to specific subdimensions of masculinity and femininity. The nature of construct measured by the scale is not a limitation provided that the predictions made with the answers to this instrument do not go beyond the a-rea that the construct it measures refers to. One limitación of this study lies in the selection of the variables chosen to validate this version of the scale. It would be interesting to investigate the relation between self-definition in gender roles terms to adhering to the sexual double standard (SDS) and SDS adhesion types. Studying gender self-definition can be extended by using this instrument in future research lines. First, in order to compare the consistency of self-definition patterns in traditional terms of masculinity (leadership competence and assertiveness) and femininity (concern for others and sociability), it would be desirable to carry out a study with participants who speak Spanish but come from from different cultures. Second, to examine in-depth debate as to whether the binary version of sex, gender and sexuality must be replaced with another non binary and fluent version, the scores on this instrument reported by participants with different sexual orientation should be compared.

It is still not known for sure if gender differences in personality derive from the evolutionary adaptations of a person’s psychology, or from a differential and binary socialization in gender roles. Nonetheless, different perspectives must prove useful to deal with this matter. From social role theories (Eagly & Wood, 2012), many gender differences must disappear in what are more egalitarian societies. In this framework, it makes sense to study whether the socio-structural division based on gender is facilitated and promoted when femininity is defined with dimensions or traits that are exercised in the private sphere (e.g., concern for others and sociability), and the masculinity with traits that are implemented in the public sphere (leadership competence and assertiveness). However, from a complementary approach, the prevalence of self-attribution of these traditional gender roles should be studied, because such self-description would end up reinforcing different and binary social patterns of behavior and attitudes in men and women.

The importance of this study lies in its potential to improve the measurement of self-attribution of traditional gender traits in the Spanish-speaking population. Studying the self-attribution of traditional gender roles will allow us in future studies to know its prevalence in the population. From a psychosocial perspective, the prevalence of traditional gender roles allows predicting different and binary social patterns of behavior and attitudes in men and women in different settings, for example, that of sexual behaviors and attitudes.